美國憲法第十三修正案

| 本條目屬於 |

| 美利堅合眾國憲法 |

|---|

|

| 序言和正文 |

| 修正案 |

|

|

| 歷史 |

| 全文 |

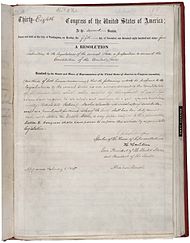

《美利堅合眾國憲法》第十三修正案(英語:Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution)簡稱「第十三修正案」(Amendment XIII),旨在廢除奴隸制和強制勞役,除非是「依法判罪的人的犯罪的懲罰」。該修正案於1864年4月8日在聯邦參議院以三分之二多數通過,再於1865年1月31日在聯邦眾議院通過,1865年12月6日獲得憲法第五條所規定的四分之三多數州批准生效。1865年12月18日,國務卿威廉·H·西華德正式宣佈修正案通過,成為南北戰爭結束後通過的三條重建修正案的第一條。

最初制訂的美國憲法中對奴隸制採取了默許的保護態度,如五分之三妥協中規定各州奴隸人口將按五分之三的比例折算成自由人口後用於確認該州在聯邦眾議院的代表席位數。在第十三修正案以前最後一次有修正案通過已經過去了超過60年時間。雖然許多奴隸已由林肯在1863年的解放奴隸宣言中宣佈恢復自由身,但他們戰後的地位仍然不明。1864年4月8日,參議院通過了廢除奴隸制的修正案。眾議院一開始的投票沒有通過,但之後還是在林肯政府的竭力推動下於1865年1月31日投票通過。幾乎所有的北方聯邦州都迅速批准了修正案,多個南北邊界以及南方部分「已經重建」的州也予以批准,讓修正案成功地在這年結束前通過。

雖然修正案正式廢除了全美各地的奴隸制,但諸如黑人法令、白人至上主義者的暴力行為和選擇性執法導致非裔美國人繼續受到強制勞役,這類情況又尤以南方州為甚。與另外兩條重建修正案不同的是,第十三修正案很少在判例法中引用,但也還是用於廢除了勞役償債制和一些基於種族的歧視行為。第十三修正案與第十四和第十五修正案的另一個不同之處在於,這條修正案對個人行為仍然適用,並不局限於國家行為。修正案還允許國會立法打擊人口販賣等現代形式的奴隸制度。

內容文本[編輯]

Section 1. Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.

Section 2. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.[1]

中文翻譯如下:

第一款 在合眾國境內受合眾國管轄的任何地方,奴隸制和強制勞役都不得存在,但作為對於依法判罪的人的犯罪的懲罰除外。

美國奴隸制度[編輯]

美國建國前的13個北美殖民地都存在奴隸制[5]。1787年制訂的美國憲法中雖未用到「奴隸制」一詞,但包括了多處與其有關的條文。如第一條第二款第3節的五分之三妥協規定眾議員名額的分配根據各州「自由人總數加上所有其他人口的五分之三予以確定」,這個「其他人口」就是指奴隸[6][2][3][7]。又如第四條第二款第3節中的勞役逃犯條款規定:「根據一州法律須在該州服勞役或勞動的人,如逃往他州,不得因他州的法律或規章而免除此種勞役或勞動」[2][3]。第一條第九款還規定國會只有在1808年後才能通過立法禁止「任何一州認為得准予入境之人的遷移或入境」[8]:16。不過在第五修正案中有這樣的規定:「無論何人……不經正當法律程序,不得被剝奪生命、自由或財產。」[2][3][9]廢奴主義者用這條修正案來攻擊奴隸制,這也是1857年斯科特訴桑福德案中將奴隸視為財產的法律基礎[10]。白人優越主義在當時美國文化上的普遍性也導致無論法律還是實踐中奴隸制都獲得了支持[11]。

從1777到1804年,所有的北方州都直接或逐步廢除了奴隸制,但沒有任何一個南方州跟隨,並且其奴隸人口數量還在不斷增長,並於1861年達到約400萬人的峰值[8]:14-16。由威廉·勞埃德·加里森等人領導的廢奴主義運動在北方發展壯大,要求在全國範圍內中止奴隸制度,導致南方和北方的關係變得日趨緊張。1836年,聯邦眾議院制定了反對廢奴主義請願和演講的堵嘴規則,試圖扼殺約翰·昆西·亞當斯和其他廢奴主義眾議員的主張。認為不同種族應保持隔離的廢奴主義者和擔心獲得自由的前景會助長奴隸叛亂的奴隸主組成了一個名為美國殖民協會的同盟,他們要求將自由的黑人和奴隸通過移民或殖民的方式送回非洲。這一觀點得到了包括亨利·克萊在內的多位政治家支持,他們擔心廢奴主義運動會挑起一場內戰[8]:20-22。1818年和1839年,聯邦眾議員阿瑟·利弗莫爾和約翰·昆西·亞當斯分別提出了淘汰奴隸制的憲法修正案,但都沒能贏得足夠的支持[12]。

隨着美國的繼續擴張,新領土上的奴隸制問題成了國家面臨的主要問題。南方州認為奴隸屬於財產,因此可以像其它任何一種財產那樣從一州移至他州[13]:123。1820年的密蘇里妥協將密蘇里州接納為一個蓄奴州,緬因州為一個自由州,由此保持聯邦參議院的地區平衡。1846年的一項撥款法案中附加了一個威爾莫特但書,其中規定在所有美墨戰爭中獲得的土地上禁止施行奴隸制,這一規定多次經眾議院投票通過,但都沒能經過參議院這關[13]:123,之後的1850年妥協案通過接納作為自由州的加利福尼亞州暫時化解了這個問題,並設立了一個更強有力的逃奴追緝法,禁止在哥倫比亞特區進行奴隸貿易,並允許新墨西哥州和猶他州在奴隸制問題上自決[8]:59。

雖然有上述的折衷方案,但南方和北方的緊張局勢在隨後的十年中仍繼續激化,這其中還受到了其它多方面因素的影響,包括1852年出版的反奴隸制小說《湯姆叔叔的小屋》[14]:88-91,1854年堪薩斯州廢奴主義勢力和支持奴隸制勢力的對抗[14]:146-150、1857年聯邦最高法院在斯科特訴桑弗特案中判定1850年妥協案違憲[14]:170-177,廢奴主義者約翰·布朗於1859年試圖在哈珀斯費里發起奴隸起義[14]:201-206以及1860年美國總統選舉的結果:反對奴隸制的共和黨人亞伯拉罕·林肯當選成為新的總統。南方各州在林肯當選幾個月後宣佈脫離聯邦,組建美利堅聯盟國,並隨即挑起了南北戰爭[14]:234-235。

通過[編輯]

1863年1月1日,林肯利用總統戰時所擁有的權力頒佈了解放奴隸宣言,宣佈南方所有叛亂州的奴隸立即恢復自由,但這並沒有對那些選擇繼續效忠聯邦的邊界州中的奴隸現狀產生影響[14]:558。林肯接着又在1863年12月宣佈大赦和重建,承諾只要南方州廢除奴隸制,並搜集占其投票人口數10%的效忠誓辭,就給予一個重返聯邦的機會[15]:47。南方州沒有輕易接受這個機會,其奴隸制的地位仍不明朗。

在內戰的最後幾年裏,北方聯邦的國會議員就多種不同的重建提案進行了辯論[15]:48-51,其中一些人提出以憲法修正案來在全國範圍內永久性地廢除奴隸制。1863年12月14日,來自俄亥俄州的聯邦眾議員占士·米歇爾·阿什利提出了一條這樣的修正案[16]。愛荷華州眾議員占士·F·威爾森也很快提出了類似的提案。1864年1月11日,密蘇里州聯邦參議員約翰·B·亨德森提交了一份廢除奴隸制憲法修正案的聯合決議案。由伊利諾州參議員萊曼·特朗布爾擔任主席的參議院司法委員會開始將各類相關的不同提議合併成修正案。

由麻省聯邦參議員查爾斯·薩姆納和賓夕凡尼亞州眾議員撒迪厄斯·史蒂文斯為代表的共和黨激進派希望可以通過一條影響更大的修正案[17]:38-42。1864年2月8日,薩姆納提交了這樣一份修正案草案:

「法律面前,人人平等,任何人都不得將他人當做奴隸。國會有權以適當立法來保證美國境內任何地區對此宣言的執行。」[18]:741-742[19]

薩姆納試圖繞開特朗布爾控制的司法委員會來增加自己提議修正案獲得通過的希望,但沒能成功[20]。2月10日,司法委員會向參議院提交了一份基於阿什利、威爾森和亨德森草案的修正案[21][22]。

委員會的版本採用了1787年《西北條例》的措辭,該條例當時主要對如今被稱為美國中西部的地區適用,其中規定:「在上述任何地方,奴隸制和強制勞役都不得存在,但作為對於依法判罪的人的犯罪的懲罰除外。」[23]不過,司法委員會採納亨德森的提議作為新草案基礎時也做了一些改動,將其中規定的修正案只需參眾兩院過半數通過和三分之二的州通過即可生效的規定刪除,所以修正案將仍像憲法第五條規定的那樣需要兩院三分之二多數通過,再由四分之三的州通過[24]。

聯邦參議院於1864年4月8日以38票支持,6票反對通過了修正案。但兩個月後聯邦眾議院的投票結果是93票支持,65票反對,距所需的三分之二多數還差13票,議員投票黨派之爭非常明顯,共和黨支持,民主黨反對[13]:686。前自由土地黨候選人約翰·C·弗里蒙特在1864年總統選舉中威脅以第三方黨派候選人參選反對林肯,不過這一次也站到了支持反奴隸制修正案的立場上。共和黨方面雖然有林肯在接受總統候選人提名的信中表示支持修正案,但還是沒有形成統一戰線[13]:624-625[8]:299。弗里蒙特於1864年9月22日退出了選舉,轉為支持林肯[13]:639。

國會辯論[編輯]

由於沒有南方州代表出席,國會也就沒有多少議員從道德或宗教信仰角度來為奴隸制辯護。反對修正案的民主黨議員通常是以聯邦主義和州權為理由展開辯論[25]:179。一些議員辯稱,這樣的修正案違背了憲法的精神,已經變成了一場「革命」而不再是一個有效的「修正」了[26]。還有一些反對者警告說,修正案將給予黑人徹底的公民權[27]:10。

共和黨議員堅稱奴隸制是野蠻的,為了民族進步有必要將之廢除[25]:182。修正案的支持者還認為奴隸制對白人也存在負面影響,例如由於需要與強制勞役競爭而不得不接受較低的工資水平,以及在南方要求廢除奴隸制的白人所遭受的壓迫。支持者聲稱,終結奴隸制可以恢復蓄奴州以審查和恐嚇手段所侵犯的第一修正案等多項憲法權利[27]:10[28]。

北方的共和黨人和部分民主黨人對廢除奴隸制的修正案感到激動,並開始就此召開會議並發佈決議[15]:61。許多黑人,特別是南方的黑人,更側重於把土地所有權和教育視為解放的關鍵[29]。隨着奴隸制開始在政治上顯得不能成立,北方的民主黨人開始逐漸宣佈他們對修正案的支持,其中包括紐約州聯邦眾議員占士·布魯克斯[30]、馬利蘭州聯邦參議員勒維迪·詹森[31]和紐約強大的政治機器坦慕尼協會[15]:203。

國會通過[編輯]

林肯一直擔心解放奴隸宣言會遭到推翻,或是在戰後失效,因此將憲法修正案視為一個更可靠的解決辦法[8]:312-314[32]。由於擔心從政治上對自己不利,他對外宣稱保持中立[33]。不過,林肯在1864年的黨綱中提出用憲法修正案來解決廢除奴隸制的問題[34][35]。贏得1864年美國總統選舉後,林肯將第十三修正案的通過當成自己在立法倡議上的頭等大事來抓,於國會還處於「跛腳鴨」時期時開始了他的努力[13]:686-687[15]:176-177, 180。民眾對修正案的支持率開始攀升,林肯又於12月6日對發表的國情咨文中向國會呼籲,修正案的通過和生效只是時間問題,考慮到所有的因素,這個時間應該是越早越好[36]。

林肯指示國務卿威廉·H·西華德和聯邦眾議員約翰·B·埃利等人使用任何必要的手段來確保修正案通過,這些手段包括承諾政府公職、政治捐款及傳出民主黨議員有意改變投票立場的消息等[8]:312-313[13]:687。西華德有大筆資金直接進行賄賂。重新在眾議院提出修正案的阿什利也成功遊說了多位民主黨議員轉為支持[13]:687-689。眾議員賽迪斯·史蒂文斯之後對此評價道:「19世紀最偉大的舉措是在美國最純潔的人的協助和教唆下,利用腐敗才通過的。」不過,林肯在這場交易中所扮演的確切角色仍然不明[37]。

由於有民意上的支持,共和黨人在1864年的國會兩院換屆選舉中再度獲勝,修正案通過的勝算因此進一步加大,議員們聲稱這毫無疑問是人民的意旨[38]。反對派則是由1864年民主黨副總統候選人,聯邦眾議員喬治·H·彭德爾頓帶隊[13]:688。共和黨則將其要求平等的激烈用詞淡化,以求獲得更多人的支持[39]。為了安撫一些批評人士對修正案會造成現有社會結構分裂的擔憂,一些共和黨人還明確承諾修正案不會對父權體制構成任何不利影響[40]。

1月中旬,眾議院議長斯凱勒·科爾法克斯估計修正案距通過還差5票,阿什利於是推遲了表決[15]:197-198。到了這個節骨眼兒上,林肯強化了對修正案的推動,直接向部分國會議員作出情感性的懇求[41]。1865年1月31日,眾議院再次對修正案發起表決,各方均未知鹿死誰手。所有的共和黨人都投了贊成票,還有16位民主黨人也投了贊成票,修正案最終以119票贊成,56票反對獲得通過,剛剛超過所需要的三分之二多數[8]:313。眾議院為此爆發了慶祝活動,一些議員當眾流下了眼淚[8]:314。黑人自之前一年開始獲許旁聽眾議院的會議,這天許多前來的人們也在旁聽席上歡呼[14]:840。

1865年2月1日,林肯在修正案上簽字,令第十三修正案成為唯一一條經總統簽字並獲得通過的美國憲法修正案,之前占士·布坎南於1861年簽置的一條支持奴隸制的修正案最終沒能在國會通過[42][43]。第十三修正案的存檔副本上就帶有林肯的簽名,位於通常由眾議院議長和參議院議長簽名的位置下方,在日期的後面[44]。2月7日,國會通過決議確認總統的簽名是不必要的[45]。林肯共計簽置了這條修正案的至少14份紀念性副本,2006年,其中的一份副本以180萬美元的價格成交[46]。

各州批准[編輯]

修正案送至各州立法部門後,大部分北方的州很快就給予了批准,不過特拉華州、肯塔基州和新澤西州沒有批准,這三個州在1864年的總統大選中也是民主黨候選人喬治·B·麥克萊倫獲勝。

這個時候戰爭尚未正式結束,戰敗南方各州的法律地位仍然模稜兩可。不過南方路易斯安那州、阿肯色州、維珍尼亞州和田納西州四州重建政府還是批准了修正案[14]:840[47]。肯塔基州將奴隸制視為對該州戰爭期間忠於南方邦聯的獎勵,因此快速而又苦澀地否決了修正案[48]:126-127。

1865年4月,林肯總統被刺殺,由於國會正在休會,繼任林肯總統職位的安德魯·詹森開始了一段史稱「總統重建」的時期,他親自監督了北卡羅萊納州、密西西比州、佐治亞州、德薩斯州、阿拉巴馬州、南卡羅萊納州和佛羅里達州七個南方州新政府的建立。詹森安排自己選中的代表召開政治會議,並極力鼓勵他們批准修正案。[49][50][51]詹森希望能在國會12月開會討論是否重新接納南方各州之前完成修正案的批准[52]。

南卡羅萊納和其他各南方州的白人政治家擔心國會可能會利用修正案賦予的執法權力授予黑人選舉權[53]。南卡羅萊納州批准修正案時發佈了其詮釋性的聲明,稱「國會任何企圖通過立法改變昔日奴隸政治地位或民事關係之舉,都將違背美利堅合眾國憲法」[54][55]。阿拉巴馬州和路易斯安那州也聲稱他們對修正案的批准並不意味着賦予聯邦改變昔日奴隸地位的權力[56][17]:48[57]。

隨着第39屆國會即將召開,西華德繼續向其它尚未批准的州施壓[15]:232。南卡羅萊納州、阿拉巴馬州、北卡羅萊納州和佐治亞州先後於1865年11和12月批准了修正案,達到內戰前已有36個州的四分之三多數標準。所有州批准的具體日期如下[58]:

- 伊利諾州:1865年2月1日

- 羅德島州:1865年2月2日

- 密芝根州:1865年2月3日

- 馬利蘭州:1865年2月3日

- 紐約州:1865年2月3日

- 賓夕凡尼亞州:1865年2月3日

- 西維珍尼亞州:1865年2月3日

- 密蘇里州:1865年2月6日

- 緬因州:1865年2月7日

- 堪薩斯州:1865年2月7日

- 麻省:1865年2月7日

- 維珍尼亞州:1865年2月9日(由臨時接管原州政府的北方軍政府批准)

- 俄亥俄州:1865年2月10日

- 印第安納州:1865年2月13日

- 內華達州:1865年2月16日

- 路易斯安那州:1865年2月17日

- 明尼蘇達州:1865年2月23日

- 威斯康星州:1865年2月24日

- 佛蒙特州:1865年3月8日

- 田納西州:1865年4月7日

- 阿肯色州:1865年4月14日

- 康涅狄格州:1865年5月4日

- 新罕布什爾州:1865年7月1日

- 南卡羅萊納州:1865年11月13日

- 阿拉巴馬州:1865年12月2日

- 北卡羅萊納州:1865年12月4日

- 佐治亞州:1865年12月6日[59]

至此批准的州已經達到全部州數的四分之三,以下各州在修正案通過並頒佈後進行了批准:

- 俄勒岡州:1865年12月8日

- 加利福尼亞州:1865年12月19日

- 佛羅里達州:1865年12月28日,並在1869年6月9日重新批准

- 愛荷華州:1866年1月15日

- 新澤西州:1866年1月23日,該州原於1865年3月16日拒絕了這一修正案

- 德薩斯州:1870年2月18日

- 特拉華州:1901年2月12日,該州原於1865年2月8日拒絕了這一修正案

- 肯塔基州:1976年3月18日,該州原於1865年2月24日拒絕了這一修正案

- 密西西比州:1995年3月16日,該州原於1865年12月5日拒絕了這一修正案[59]

西華德接受了南卡羅萊納州和阿拉巴馬州對修正案的有條件批准[15]:232,並於1865年12月18日正式宣佈修正案已於12月6日(佐治亞州批准當天)通過,佐治亞州是第27個批准的州,進而還確認了所有36個州都是聯邦的有效成員[60][61]。

俄勒岡州和加利福尼亞州於1865年12月中旬批准修正案,佛羅里達州於1865年12月28日批准[60],愛荷華州和新澤西州於1866年1月批准[62],德薩斯州於1870年批准[60],特拉華州1901年批准[63],肯塔基州在1976年批准[63],密西西比州議會一直到1995年才批准修正案,並且遲至2013年2月才正式告知聯邦註冊辦公室,完成該州批准修正案的法律程序[64]。

效果[編輯]

第十三修正案從法律上禁止奴隸制和強制勞役,除非是依法對犯罪行為加以懲罰,還修正了憲法正文中對奴隸制的相關規定[65][66]。雖然肯塔基州的大部分奴隸都已經解放,但仍有6.5至10萬人直到12月18日憲法開始生效時才在法律上獲得了自由[67][48]:82。而特拉華州有大量奴隸已經在內戰期間逃亡,所以只有約900人從法律上獲得了自由[48]:82[68]。

隨着第十三修正案在國會通過,共和黨逐漸開始擔心國會中被民主黨主控的南方州議員席位將大幅增長,因為這些州原本大都有較大數量的黑奴。根據原本憲法第一條中的五分之三妥協,每名黑奴按五分之三個自由人計算,而在第十三修正案通過後,所有黑奴都成了自由人,所以無論獲得自由的黑人是否會投票,根據各州人口數分配的聯邦眾議院議席都將出現戲劇性的增長[69]:22[70]:111。共和黨希望通過吸納和保護新增黑人選民的選票來抵消民主黨的增長。[69]:22[71][70]:112

南方的政治和經濟變革[編輯]

南方在文化上仍然保留着非常濃郁的種族歧視色彩,留在這些地區的黑人面臨着危險的處境。J·J·格里斯(J. J. Gries)在給國會重建委員會的報告中稱,南方許多地區有一種先天性的、揮之不去的期望,要將奴隸制以其他的形式重新建立起來,並且由於剛剛獲得自由的黑人失去了之前奴隸主出於利益角度對其進行的保護,所以情況可能會更糟。[72] W·E·B·杜波依斯於1935年寫道:

即便第十三修正案通過後,奴隸制也沒有廢除。這400萬獲得自由的人們大部分還是像解放前一前,在同一個種植園做同一份工作,只不過這份工作因戰爭及其所帶來的劇變有所中斷而已。此外,他們的工資也沒變,只不過以前的奴隸代碼修改成了姓名。兵營中、城市的街道上有着成千上萬(以前是奴隸而)逃亡的人,他們無家可歸,還要面對貧困和疾病的威脅。除了一些特殊情況外,他們是自由了,但沒有土地,沒有錢,沒有身份,也沒有任何保護[73][74]

正式的解放並沒有改變留在南方大多數黑人的經濟狀況。[75]由於修正案仍然允許用強制勞役來懲罰犯罪行為,南方各州於是開始制訂一系列環環相扣的法律來讓黑人淪為刑事罪犯[76]:53。這些在黑人獲得解放後通過或更新的法律被統稱為黑人法令[70]:111。密西西比州是第一個通過這類法令的州,這項1865年通過的法律題為《賦予自由民公民權利的法案》(An Act to confer Civil Rights on Freedmen)[77],要求黑人工人在每年1月1日與白人農場主簽訂合同,否則將面臨流浪罪的懲罰[76]:53。黑人如果犯下輕盜竊罪、講粗話或是在日落後出售棉花,都會被判處強制勞役[76]:100。各州通過了新的,更嚴格的流浪法,選擇性地針對那些沒有白人保護的黑人[76]:53[17]:51-52,被定罪的黑人將被賣到農場、工廠、伐木營地、採石場和礦山[76]:6。

1865年11月批准第十三修正案後,南卡羅萊納州議會立即開始制訂黑人法令[78]。該法令針對所有擁有超過一位黑人曾祖輩的人規定了單獨的一套法律、懲罰和可以接受的行為準則。根據這樣的法令,黑人的憲法權力已所剩無幾,並且終身只能做農民或僕人[79]。而對黑人土地所有權所做的限制也將令其經濟上永遠都處於屈從的地位[29]。

有些州規定了長度沒有限制的兒童「學徒」時期[17]:50,有些法律表面看來不是特別針對黑人,而是對農場工人有影響,而絕大部分的農場工人又都是黑人。同時還有多個州通過法律主動防止黑人獲得物業[17]:51。

南方企業主開始重新啟用一種名叫勞役償債制的奴役系統,其手下工人為償還被陷害而借下的貸款被迫無限期地為企業主工作[80][81],利用南方的重建,企業主誘捕了南方的很大一部分黑人,令其身陷勞役償債制中無法自拔[82]。這些工人仍然一貧如洗,還被逼迫從事危險性較高的工作,並進一步在南方吉姆·克勞法的管控下合法地受到限制和迫害[81]。勞役償債制與奴隸制的不同點在於,前者不是嚴格的世襲制度,也不允許像後者那樣完全把人當成財產來銷售。但是,一個人的債務仍然可以進行銷售,所以實際效果也和奴隸制的直接銷售奴隸類似,整個系統的運作在許多方面都和南北戰爭前的奴隸制非常相似[83]。

國會和行政執行[編輯]

1866年民權法是國會首度行使第十三修正案賦予的立法權,該法保證了黑人的公民權和平等法律保護,但沒有保護投票權。修正案還成為多項自由民管理局法案的授權基礎。總統安德魯·詹森否決了這些法案,但國會以絕對多數推翻了他的否決,通過了1866年民權法和第二部自由民管理局法案。[15]:233-234[84]

包括特朗布爾和威爾森在內的法案支持者認為,第十三修正案的第二款授權聯邦政府為各州的公民權利立法。其他人對此不同意,認為新出現的不平等與之前奴隸制所導致的不同[56]:1788-1790。由於擔心未來反對者會再次試圖推翻現有立法,也為國會立法提供更充足的理據,國會和各州增加了進一步的憲法保護:1868年通過的第十四修正案對美國公民作出了定義,並提供平等的法律保護,1870年通過的第十五修正案則保護了黑人的投票權。[69]:23-24

自由民局在部分地區為受黑人法案管制的人們提供一定程度的支持[85],第十三修正案也是該局在肯塔基州開展工作的法律依據。民權法案則通過允許黑人在聯邦法院進行訴訟來繞過地方司法管轄所存在的種族主義行徑。[48]:99-100, 105

1870至1871年的執法法和1875年民權法案旨在打擊白人至上主義者對黑人的暴力和恐嚇行為,同時也部分起到了結束南方黑人奴隸處境的作用[17]:66-67。不過,這些法律的效果由於政治意願的減弱和聯邦政府在南部失去了權威而削弱,特別是在共和黨人為保住總統席位而達成1877年妥協結束重建以後[86]。

勞役償債製法[編輯]

國會通過1867年勞役償債製法廢止了勞役償債制[87]:1638,特別禁止任何人以任何自願或被迫的形式以做苦工來償還任何債務或義務[88]。

1939年,聯邦司法部建立了民權分支,主要注重於對第一修正案和勞工權利的保護[87]:1616。第二次世界大戰也帶來了國內和國外對奴隸制和強制勞役問題越來越多的關注,對極權主義的推敲也逐漸增多[87]:1619-1621。美國力求以打擊南方勞役償債制來提高其在種族問題上的公信力和國際形象[87]:1626-1628。在聯邦司法部長法蘭西斯·貝弗利·比德爾的帶領下,民權部門援引第十三修正案和重建時期的立法來作為其行動的法律依據[87]:1629, 1635。

1947年,聯邦司法部成功檢控伊利沙伯·英格爾斯(Elizabeth Ingalls)奴役家僕多拉·L·瓊斯(Dora L. Jones)。法院認為瓊斯「是一個完全受被告意志操控的人,她沒有行動自由,完全是在被告的控制之下進行服務,並且她對被告的服務是被強迫的。」[87]:1668第十三修正案在這一期間受到了的關注大幅增加,但從1954年的布朗訴托皮卡教育局案到1968年的瓊斯訴阿爾弗雷德H·梅耶公司案,修正案的風頭都遠遠不及第十四修正案[87]:1680-1683。

人口販運[編輯]

受到強迫參加勞動的人口販運受害者通常會受到脅迫,他們都受美國法典第18條的保護。[89]

- 美國法典第18條第241款(Title 18, U.S.C., Section 241)——陰謀侵犯權利罪中規定,任何人如果陰謀損害、欺壓、威脅或恐嚇任何人由憲法或美國法律保障的權利或特權,可以處以10年以下有期徒刑並處罰金,如果在違反本條的過程中因涉及綁案、性暴力、謀殺而導致受害人死亡,則可以判處十年以上有期徒刑、無期徒刑直至死刑。[90]

- 美國法典第18條第242款(Title 18, U.S.C., Section 242)——執行基於膚色法律剝奪權利案中則規定,任何人執行任何聯邦、州或地方的基於膚色剝奪他人憲法或美國法律所保障的權利或特權即為犯罪,可以判處一年以下有期徒刑並處罰金,同時不得根據一人的膚色、種族和國籍為由給予其任何與他人不同等級的懲罰。如果在這一過程中使用、試圖使用或威脅使用危險的武器、炸藥等方式(強迫他人屈服),可以處以十年以下有期徒刑並處罰金。如果在違反本條的過程中因涉及綁案、性暴力、謀殺而導致受害人死亡,則可以判處十年以上有期徒刑、無期徒刑直至死刑。[91]

聯邦司法部定義[編輯]

- 勞役償債制和強制勞役:

勞役償債制指一個人因為債務支付問題而在非自願情況下通過勞役來清償債務的情況。強制勞役指一個人被他人以武力脅迫或是以武力相要脅,亦或被威脅受法律強制手段打擊而被迫作他人的奴隸,或是被迫勞役和提供服務。這其中還包括他人使用武力或威脅使用武力亦或威脅通過法律強制手段而造成的「恐懼氣氛」下被迫工作。[92]在1911年的貝利訴阿拉巴馬州案中,聯邦最高法院裁定債役法(指強制他人參加勞役來償還債務的法律)違反了第十三修正案中禁止強制勞役的規定[93]。

一些學者和法院認為一些個人服務合同在違約補救措施中要求特定履行的做法屬於強制勞役的一種形式,不過其他法院和學者批駁了這一看法。在學術界和一些地方司法管轄區,這樣的規則較為流行,但從未獲得過上級法院的支持。[94]

- 強迫勞動:

強迫勞動或服務包括:

- 受到嚴重的身體約束或傷害的威脅而被迫參加勞動;

- 以任何計劃、方案或模式旨在讓人相信,自己如果不參加某些勞動或服務,將會遭到嚴重的身體約束或傷害;

- 濫用或威脅濫用法律或法律程序來迫使他人參加勞動。[92][95]

司法解讀[編輯]

與另外兩條重建修正案不同,第十三修正案很少在之後的判例法中引用。正如歷史學家艾米·德魯·斯坦利(Amy Dru Stanley)所總結的那樣:「除了曲指可數的幾個推翻勞役償債制、公然的強制勞役和某些情況下基於種族的暴力和歧視行為的里程碑式判決外,第十三修正案從來都不是權利訴求的一個有力來源。」[18]:735[96]

黑人奴隸及其後裔[編輯]

1866年的美國訴羅德島州案是有關第十三修正案最早的案件之一,該案考驗的是1866年民權法案中有關黑人可以在聯邦法院申訴這一規定的合憲性。當時肯塔基州有法律禁止黑人到法庭作證指控白人,所以「非洲種族美國公民」蘭茜·塔爾博特(Nancy Talbot)只能到聯邦法院起訴一名對她實施了搶劫的白人。塔爾博特到聯邦法院起訴後,肯塔基州最高法院裁定這一聯邦法令違憲。擔任肯塔基巡迴法院法官的聯邦最高法院大法官諾亞·斯韋恩推翻了肯塔基州最高法院的判決,認為如果沒有民權法中的這一執法手段,奴隸制不會真正被廢除。[97][17]:62-63[98]。而在1867年的一個案件中,美國首席大法官薩蒙·蔡斯下令恢復馬利蘭州一位前奴隸的自由,這位名叫伊利沙伯·特納的女子被之前的主人以契約束縛,成為事實上的奴隸[17]:63-64。

在1872年的布萊尤訴美國案中,聯邦最高法院受理了另一個有關肯塔基州聯邦法院民權法案的訴訟。約翰·布萊尤(John Bylew)和喬治·肯納德(George Kennard)是兩個白人,他們一起造訪了住在木屋中的一戶姓福斯特的黑人家庭。布萊尤顯然因什麼事情而對李察·福斯特(Richard Foster)非常生氣,用斧頭兩次打中對方的頭部。然後與肯納德一起殺死了李察的母親莎莉·福斯特(Sallie Foster)和父親傑克·福斯特(Jack Foster),還殺了其失明的祖母露西·阿姆斯特朗(Lucy Armstrong),重傷了福斯特的兩名幼女。肯塔基州法院不允許福斯特的孩子們出庭作證指控布萊尤和肯納德。但聯邦法院依據民權法案授權介入,判處兩名被告謀殺罪名成立。最高法院最終以5比2判決福斯特的孩子們也不能在聯邦法院作證,因為只有在世的人才能夠利用這一法案(意思是原告的家人如果沒有死,才能親自出庭做證,孩子並沒有就長輩的謀殺罪作證的權利)。法院這一裁決意味着第十三修正案沒有允許聯邦政府在謀殺案中進行司法補救。斯韋恩和約瑟夫·P.布拉德利兩名大法官投下了反對票,認為第十三修正案如果要產生有意義的影響,就必須應對這類系統性的種族壓迫。[99][17]:64-66

從技術上來說,布萊尤案是一個對州和聯邦法院都有約束力的先例,這導致國會由第十三修正案所賦予的權力受到明顯削弱。最高法院之後繼續堅持這一立場,在1873年的屠宰場案中,法院支持了由州政府保障的白人屠夫壟斷地位[100]。在1876年的美國訴克魯克香克案中,法院無視了巡迴法院法官有關第十三修正案為依據的意見,免除了科爾法克斯大屠殺兇手的刑事責任,並裁定1870年執法法無效。[101][17]:66-67

在1883年的一組民權案件中,最高法院把5個有關1875年民權法案的案件合併審查,該法禁止在「旅館、地面或水域的公共交通工具、劇院和其它公共娛樂場所」的種族歧視行為。法院認為第十三修正案對大部分非政府行為的種族歧視行徑沒有約束力。[69]:122大法官布拉德利在多數意見中認為,第十三修正案賦予國會取締奴隸制的權力,但這種權力對個人行為無效,他還認為第十三修正案中保護的公民基本權力與人們在社會中生活的社會權利有所區別[17]:70。多數意見認為,1875年民權法案將導致有關奴隸制的爭論深入到現實生活中的每一個角落,但人們有時候會因為個人生計、工作、業務等方面的需要來作出一些可能會被認為存在歧視的行為,據此而以法律加以限制和懲罰是不妥當的[103]。肯塔基州律師出身的大法官約翰·馬歇爾·哈倫在目睹了有組織的種族暴力活動後改變了自己對民權法案的看法,他在法院唯一的反對意見中稱,這種由團體或個人在行使公共或准公共職能時表現出的歧視是一種代表性的奴役制度,國會應當對其加以取締。[17]:73[104]

在1896年的普萊西訴弗格森案中,普萊西的律師向法院申訴稱種族隔離制度從實質上違反了第十三修正案,但最高法院沒有接受這一說法,以7比1的投票結果支持了州法律中根據隔離但平等原則強制種族隔離的法律。法院認為,白人和有色人種由於膚色上永遠都有顯著的區別,僅僅是從法律上加以分隔並不會對兩個種族在法律上的平等地位構成威脅,也不意味着強制勞役會重新出現。[69]:162, 164-165哈倫大法官再次寫下了自己孤獨的異議,稱再也不應該用這種所謂「平等」的偽裝去繼續誤導任何人了。[17]:78[105]

在1906年的霍奇斯訴美國案中,法院推翻了一條聯邦法規,該法規中對任何兩個或更多數目的人陰謀損害、欺壓、威脅或恐嚇任何人自由行使或享受憲法和美國法律保障的權利或特權的行為提供了懲罰依據。在該案中,阿肯色州的一組白人密謀以暴力手段阻止8名黑人到一家木材廠工作,這些白人被聯邦大陪審員定罪。最高法院判決該聯邦法規沒有第十三修正案的授權。認為這不過是個人行為,不受憲法修正案的限制。哈倫再次寫下反對意見,堅持自己有關第十三修正案的保護應當不只是「人身自由」而已。[106][17]:79-80法院又在1922年的柯瑞根訴巴克利案判決中再次重申了霍奇斯案的意見,稱第十三修正案對地役權不適用[107]。

聯邦民權法案在南方的實施造就了不計其數的勞役償債制案件,經歷了漫長的司法之路。最高法院在1905年的克萊亞特訴美國案中裁決,勞役償債制屬於強制勞役。法院認為,雖然僱員證詞中稱,有些工人是自願簽訂合同,但勞役償債制從本質上就是非自願的。[108]:983[109]

瓊斯案及後續[編輯]

法律史將1968年的瓊斯訴艾爾弗雷德·H·邁耶公司案視為第十三修正案判例法的一個轉折點[110][27]:2。最高法院在該案判決認為國會可以「合理」地對個人的種族歧視和強制勞役行為作出限制[110]。瓊斯夫婦居住在密蘇里州的聖路易斯縣,他們起訴的是當地一家拒絕賣房子給他們的房地產公司。法院的判決是以7比2的投票結果作出的。判決書中稱內戰結束後用來限制黑人自由行使權利的黑人法令是奴役系統的替代品,將黑人排除在白人社會以外。這種因他人膚色而拒絕其購買房產意向的做法無疑也是奴隸制的遺留。判決書中還表示,無論北方還是南方的黑人公民,都視第十三修正案為自由的保證,這些自由包括他們的來去自由和買賣自由。如果國會連黑人用同樣的錢買到和白人同樣東西,住在白人能住的房裏這樣的權利都不能保證,那麼修正案也就成了一張白紙。如果國會連做為一個自由公民的這一點權利都保護不了,那麼第十三修正案就做出了一個這個國家無法遵守的承諾。[111]這一案件的裁決也就將美國當代社會中的種族主義問題與歷史上的奴隸制問題聯繫了起來[27]:3-4。

瓊斯案的先例之後被用來支持國會保護外來務工人員和打擊性拐賣活動的行動[112]。第十三修正案的直接執法權與第十四修正案形成了鮮明的對比,後者只能對抗政府行為下的體制性歧視,而前者可以針對個人和團體行為[113]。

其他強制勞役案件[編輯]

對於不是黑人(非裔)後裔美國公民的強制勞役案件,最高法院給予了較為狹隘的解釋。在1897年的羅伯遜訴鮑德溫案中,幾位水手拒絕履行出海義務後被強迫上船,返回後因未履行職責而遭到起訴,依據是一項聯邦法律。他們於是向法院起訴,稱該法律違反第十三修正案中的強制勞役禁令。法院的多數意見認為,第十三修正案不是用來對這類一直存在特殊性的工作加以干涉的。「在知情和願意的情況下進入的受束縛狀態不能被稱為非自願的」,士兵、海員等工作屬於這些特殊性的例外。哈倫大法官像多個案件中一樣獨自給出了異議,對第十三修正案的保護給予較為寬泛的解釋。「一個人立約為他人的私事提供個人服務的情況,從他被迫違背其意願繼續這種服務之時起,就變成了非自願束縛的情況。」[114][108]:977[115]

在1918年包括阿維爾訴美國案在內的一系列選擇性法律草案案件中,最高法院認為徵兵制不屬於強制勞役[116]。在1988年的美國訴科茲明斯基案中[117],最高法院認為以心理脅迫達成的強制勞役不受第十三修正案限制[118][119]。這一判決將第十三修正案禁止的強制勞役範圍限制在:1、以實際武力相威脅;2、以政府實際制訂的法律相威脅;3、對未成年人或移民、智商不健全人士進行欺詐或欺騙來加以奴役[117]。

美國聯邦上訴法院先後在多個案件中裁決一些高校要求學生提供社區服務後才能畢業的做法不違反第十三修正案。[120]

之前提出過的第十三修正案[編輯]

美國憲法第十二修正案通過後,一直過了超過60年才有了第十三修正案的通過。在這段時間裏,國會還曾提出過兩條憲法修正案,但均未獲得足夠州的批准。

- 貴族頭銜修正案由聯邦參議院1810年4月26日通過,同年5月10日在聯邦眾議院通過,但一共只得到了12個州的批准。該修正案規定,如果任何一位美國公民接受別國的貴族頭銜或是在沒有得到國會同意的情況下接受任何別國的報酬,則將被剝奪其公民身份。[121]

- 柯爾溫修正案於1861年2月28日在眾議院以三分之二多數通過,再於1861年3月2日在參議院以三分之二多數通過。不過之後只得到了俄亥俄和馬利蘭兩個州的批准[122][8]:158。該修正案由之後將成為國務卿的威廉·H·西華德起草,俄亥俄州聯邦參議員湯馬士·科溫推動。提議禁止國會通過任何法律來取消或限制奴隸制,並且還禁止將來再通過憲法修正案來試圖達到這個目的。這條修正案原本是作為一個勸說南方各州不要扯旗選擇脫離聯邦的妥協方案,但事實證明這沒有成功[8]:156。

亞伯拉罕·林肯在他於1861年3月4日發表的首次就職演講中特別提到了柯爾溫修正案,表示對其沒有反對意見,稱其中的思想已經體現在憲法條文中。[8]:156[123][124]

參考資料[編輯]

- ^ 13th Amendment. Legal Information Institute. Cornell University Law School. 2012-11-20 [2013-09-25]. (原始內容存檔於2013-09-01).

- ^ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 任東來; 陳偉; 白雪峰; Charles J. McClain; Laurene Wu McClain. 附录二 美利坚合众国宪法及修正案. 美国宪政历程:影响美国的25个司法大案. 中國法制出版社. 2004年1月. ISBN 7-80182-138-6.

- ^ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 李道揆. 美国政府和政治(下册). 商務印書館. 1999: 775–799.

- ^ Kenneth M. Stampp. The Imperiled Union:Essays on the Background of the Civil War. Oxford University Press. 1980: 85 [2013-09-28]. (原始內容存檔於2013-10-09).

- ^ Friedman, Lawrence Meir. Law in America: A Short History. Random House. 2004: 69 [2013-09-25]. ISBN 9780812972856. (原始內容存檔於2013-10-09).

- ^ 陳偉. 第八章 引发美国内战的司法判决——斯科特诉桑弗特案(1857). 美国宪政历程:影响美国的25个司法大案. 中國法制出版社. 2004年1月: 一、美國憲法暗藏殺機. ISBN 7-80182-138-6.

- ^ Jean Allain. The Legal Understanding of Slavery: From the Historical to the Contemporary. Oxford University Press. 2012: 117 [2013-09-25]. (原始內容存檔於2013-10-09).

- ^ 8.00 8.01 8.02 8.03 8.04 8.05 8.06 8.07 8.08 8.09 8.10 8.11 Foner, Eric. The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery. W. W. Norton. 2010 [2013-06-04]. ISBN 978-0-393-06618-0. (原始內容存檔於2013-10-09).

- ^ Jean Allain. The Legal Understanding of Slavery: From the Historical to the Contemporary. Oxford University Press. 2012: 119–120 [2013-09-25]. (原始內容存檔於2013-10-09).

- ^ Tsesis, Alexander. The Thirteenth Amendment and American Freedom: A Legal History. New York: New York University Press. 2004: 14. ISBN 0814782760.

Nineteenth century apologists for the expansion of slavery developed a political philosophy that placed property at the pinnacle of personal interests and regarded its protection to be the government's chief purpose. The Fifth Amendment's Just Compensation clause provided the proslavery camp with a bastion for fortifying the peculiar institution against congressional restrictions to its spread westward. Based on this property-rights centered argument, Chief Justice Roger B. Taney, in Dred Scott v. Sanford (1857), found the Missouri Compromise unconstitutionally violated due process.

- ^ Tsesis, Alexander. The Thirteenth Amendment and American Freedom: A Legal History. New York: New York University Press. 2004: 18-23. ISBN 0814782760.

Constitutional protections of slavery coexisted with an entire culture of oppression. The peculiar institution reached many private aspects of human life, for both whites and blacks. [...] Even free Southern blacks lived in a world so legally constricted by racial domination that it offered only a deceptive shadow of freedom.

- ^ Vile, John R. (編). Thirteenth Amendment. Encyclopedia of Constitutional Amendments, Proposed Amendments, and Amending Issues: 1789 - 2002. ABC-CLIO: 449–452. 2003.

- ^ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 13.6 13.7 13.8 Goodwin, Doris Kearns. Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln. Simon & Schuster. 2005 [2013-09-25]. ISBN 978-0-7432-7075-5. (原始內容存檔於2013-10-09).

- ^ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 14.5 14.6 14.7 McPherson, James M. Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era. Oxford University Press. 1988 [2013-09-25]. ISBN 978-0-19-503863-7. (原始內容存檔於2013-10-09).

- ^ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 15.5 15.6 15.7 15.8 Vorenberg, Michael. Final Freedom: The Civil War, the Abolition of Slavery, and the Thirteenth Amendment. Cambridge University Press. 2001 [2013-09-25]. ISBN 9781139428002. (原始內容存檔於2013-09-29).

- ^ James Ashley. Ohio History Central. Ohio Historical Society. [2013-09-25]. (原始內容存檔於2013-09-25).

- ^ 17.00 17.01 17.02 17.03 17.04 17.05 17.06 17.07 17.08 17.09 17.10 17.11 17.12 17.13 Tsesis, Alexander. The Thirteenth Amendment and American Freedom: A Legal History. New York: New York University Press. 2004. ISBN 0814782760.

- ^ 18.0 18.1 Amy Dru Stanley. Instead of Waiting for the Thirteenth Amendment: The War Power, Slave Marriage, and Inviolate Human Rights. American Historical Review. 2010-06, 115 (3).

- ^ Michigan State Historical Society. Historical collections. Michigan Historical Commission. 1901: 582 [2013-09-26]. (原始內容存檔於2013-10-09).

- ^ Vorenberg, Michael. Final Freedom: The Civil War, the Abolition of Slavery, and the Thirteenth Amendment. Cambridge University Press. 2001: 52–53 [2013-09-25]. ISBN 9781139428002. (原始內容存檔於2013-09-29).

Sumner made his intentions clearer on February 8, when he introduced his constitutional amendment to the Senate and asked that it be referred to his new committee. So desperate was he to make his amendment the final version that he challenged the well-accepted custom of sending proposed amendments to the Judiciary Committee. His Republican colleagues would hear nothing of it.

- ^ Congressional Proposals and Senate Passage (The Creation of the 13th Amendment). Harpers Weekly. [2013-09-26]. (原始內容存檔於2013-01-15).

- ^ Vorenberg, Michael. Final Freedom: The Civil War, the Abolition of Slavery, and the Thirteenth Amendment. Cambridge University Press. 2001: 53 [2013-09-25]. ISBN 9781139428002. (原始內容存檔於2013-09-29).

It was no coincidence that Trumbull's announcement came only two days after Sumner had proposed his amendment making all persons 'equal before the law.' The Massachusetts senator had spurred the committee into final action.

- ^ McAward, Jennifer Mason. McCulloch and the Thirteenth Amendment (PDF). Columbia Law Review. 2012, 112: 1786. (原始內容 (PDF)存檔於2016-01-21).

There shall be neither slavery nor involuntary servitude in the said territory, otherwise than in punishment of crimes, whereof the party shall have been duly convicted.

- ^ Vorenberg, Michael. Final Freedom: The Civil War, the Abolition of Slavery, and the Thirteenth Amendment. Cambridge University Press. 2001: 54 [2013-09-25]. ISBN 9781139428002. (原始內容存檔於2013-09-29).

Although it made Henderson's amendment the foundation of the final amendment, the committee rejected an article in Henderson's version that allowed the amendment to be adopted by the approval of only a simple majority in Congress and the ratification of only two-thirds of the states.

- ^ 25.0 25.1 Benedict, Michael Les. Constitutional Politics, Constitutional Law, and the Thirteenth Amendment. Maryland Law Review. 2012-10-31, 71 (1) [2013-09-26]. (原始內容存檔於2013-09-28).

- ^ Benedict, Michael Les. Constitutional Politics, Constitutional Law, and the Thirteenth Amendment. Maryland Law Review. 2012-10-31, 71 (1): 179–180 [2013-09-26]. (原始內容存檔於2013-09-28).

(Benedict quotes Sen. Garrett Davis:) there is a boundary between the power of revolution and the power of amendment, which the latter, as established in our Constitution, cannot pass; and that if the proposed change is revolutionary it would be null and void, notwithstanding it might be formally adopted.

Full text of Davis's speech, with comments from others can be found in Great Debates in American History (頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館) (1918), ed. Marion Mills Miller. - ^ 27.0 27.1 27.2 27.3 Colbert, Douglas L. Liberating the Thirteenth Amendment. Harvard Civil Rights – Civil Liberties Law Review. 1995, 30.

- ^ TenBroek, Jacobus. Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States: Consummation to Abolition and Key to the Fourteenth Amendment. California Law Review. 1951-06, 39 (2): 180.

It would make it possible for white citizens to exercise their constitutional right under the comity clause to reside in Southern states regardless of their opinions. It would carry out the constitutional declaration "that each citizen of the United States shall have equal privileges in every other state." It would protect citizens in their rights under the First Amendment and comity clause to freedom of speech, freedom of press, freedom of religion and freedom of assembly.

- ^ 29.0 29.1 Trelease, Allen W. White Terror: The Ku Klux Klan Conspiracy and Southern Reconstruction. New York: Harper & Row. 1971: xvii.

Negroes wanted the same freedom that white men enjoyed, with equal prerogatives and opportunities. The educated black minority emphasized civil and political rights more than the masses, who called most of all for land and schools. In an agrarian society, the only kind most of them knew, landownership was associated with freedom, respectability, and the good life. It was almost universally desired by Southern blacks, as it was by landless peasants the world over. Give us our land and we can take care of ourselves, said a group of South Carolina Negroes to a Northern journalist in 1865; without land the old masters can hire us or starve us as they please.

- ^ Vorenberg, Michael. Final Freedom: The Civil War, the Abolition of Slavery, and the Thirteenth Amendment. Cambridge University Press. 2001: 73 [2013-09-25]. ISBN 9781139428002. (原始內容存檔於2013-09-29).

The first notable convert was Representative James Brooks of New York, who, on the floor of Congress on February 18, 1864, declared that slavery was dying if not already dead, and that his party should stop defending the institution.

- ^ Vorenberg, Michael. Final Freedom: The Civil War, the Abolition of Slavery, and the Thirteenth Amendment. Cambridge University Press. 2001: 74 [2013-09-25]. ISBN 9781139428002. (原始內容存檔於2013-09-29).

The antislavery amendment caught Johnson's eye, however, because it offered an indisputable constitutional solution to the problem of slavery.

- ^ Donald, David Herbert. Lincoln. Simon & Schuster. 1996: 396 [2013-09-26]. ISBN 978-0-684-82535-9. (原始內容存檔於2013-10-09).

- ^ Vorenberg, Michael. Final Freedom: The Civil War, the Abolition of Slavery, and the Thirteenth Amendment. Cambridge University Press. 2001: 48 [2013-09-25]. ISBN 9781139428002. (原始內容存檔於2013-09-29).

The president worried that an abolition amendment might foul the political waters. The amendments he had recommended in December 1862 had gone nowhere, mainly because they reflected an outdated program of gradual emancipation, which included compensation and colonization. Moreover, Lincoln knew that he did not have to propose amendments because others more devoted to abolition would, especially if he pointed out the vulnerability of existing emancipation legislation. He was also concerned about negative reactions from conservatives, particularly potential new recruits from the Democrats.

- ^ Willis, John C. Republican Party Platform, 1864. University of the South. [2013-09-26]. (原始內容存檔於2013-03-29).

Resolved, That as slavery was the cause, and now constitutes the strength of this Rebellion, and as it must be, always and everywhere, hostile to the principles of Republican Government, justice and the National safety demand its utter and complete extirpation from the soil of the Republic; and that, while we uphold and maintain the acts and proclamations by which the Government, in its own defense, has aimed a deathblow at this gigantic evil, we are in favor, furthermore, of such an amendment to the Constitution, to be made by the people in conformity with its provisions, as shall terminate and forever prohibit the existence of Slavery within the limits of the jurisdiction of the United States.

- ^ 1864: The Civil War Election. Get Out the Vote. Cornell University. 2004 [2013-09-26]. (原始內容存檔於2013-06-07).

Despite internal Party conflicts, Republicans rallied around a platform that supported restoration of the Union and the abolition of slavery.

- ^ Vorenberg, Michael. Final Freedom: The Civil War, the Abolition of Slavery, and the Thirteenth Amendment. Cambridge University Press. 2001: 178 [2013-09-25]. ISBN 9781139428002. (原始內容存檔於2013-09-29).

there is only a question of time as to when the proposed amendment will go to the States for their action. And as it is to so go, at all events, may we not agree that the sooner the better?

- ^ Donald, David Herbert. Lincoln. Simon & Schuster. 1996: 554 [2013-09-26]. ISBN 978-0-684-82535-9. (原始內容存檔於2013-10-09).

the greatest measure of the nineteenth century was passed by corruption, aided and abetted by the purest man in America

- ^ Vorenberg, Michael. Final Freedom: The Civil War, the Abolition of Slavery, and the Thirteenth Amendment. Cambridge University Press. 2001: 187 [2013-09-25]. ISBN 9781139428002. (原始內容存檔於2013-09-29).

But the clearest sign of the people's voice against slavery, argued amendment supporters, was the recent election. Following Lincoln's lead, Republican representatives like Godlove S. Orth of Indiana claimed that the vote represented a 'popular verdict . . . in unmistakable language' in favor of the amendment.

- ^ Vorenberg, Michael. Final Freedom: The Civil War, the Abolition of Slavery, and the Thirteenth Amendment. Cambridge University Press. 2001: 191 [2013-09-25]. ISBN 9781139428002. (原始內容存檔於2013-09-29).

The necessity of keeping support for the amendment broad enough to secure its passage created a strange situation. At the moment that Republicans were promoting new, far-reaching legislation for African Americans, they had to keep this legislation detached from the first constitutional amendment dealing exclusively with African American freedom. Republicans thus gave freedom under the antislavery amendment a vague construction: freedom was something more than the absence of chattel slavery but less than absolute equality.

- ^ Vorenberg, Michael. Final Freedom: The Civil War, the Abolition of Slavery, and the Thirteenth Amendment. Cambridge University Press. 2001: 191–192 [2013-09-25]. ISBN 9781139428002. (原始內容存檔於2013-09-29).

One of the most effective methods used by amendment supporters to convey the measure's conservative character was to proclaim the permanence of patriarchal power within the American family in the face of this or any textual change to the Constitution. In response to Democrats who charged that the antislavery was but the first step in a Republican design to dissolve all of society's foundations, including the hierarchical structure of the family, the Iowa Republican John A. Kasson denied any desire to interfere with 'the rights of a husband to a wife' or 'the right of [a] father to his child.

- ^ Vorenberg, Michael. Final Freedom: The Civil War, the Abolition of Slavery, and the Thirteenth Amendment. Cambridge University Press. 2001: 198 [2013-09-25]. ISBN 9781139428002. (原始內容存檔於2013-09-29).

It was at this point that the president wheeled into action on behalf of the Amendment […] Now he became more forceful. To one representative whose brother had died in the war, Lincoln said, 'your brother died to save the Republic from death by the slaveholders' rebellion. I wish you could see it to be your duty to vote for the Constitutional amendment ending slavery.

- ^ Harrison, John. The Lawfulness of the Reconstruction Amendments. University of Chicago Law Review. Spring 2001, 68 (2): 389 [2013-09-26].

For reasons that have never been entirely clear, the amendment was presented to the President pursuant to Article I, Section 7, of the Constitution, and signed.

- ^ Thorpe, Francis Newton. The Constitutional History of the United States, vol. 3: 1861 – 1895. Chicago: Callaghan. 1901: 154 [2013-09-26]. (原始內容存檔於2016-04-01).

The President signed the joint resolution on the first of February. Somewhat curiously the signing has only one precedent, and that was in spirit and purpose the complete antithesis of the present act. President Buchanan had signed the proposed Amendment of 1861, which would make slavery national and perpetual.

- ^ Joint Resolution Submitting 13th Amendment to the States; signed by Abraham Lincoln and Congress. The Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress: Series 3. General Correspondence. 1837-1897. Library of Congress. [2013-09-26]. (原始內容存檔於2013-07-22).

- ^ Thorpe, Francis Newton. The Constitutional History of the United States, vol. 3: 1861 – 1895. Chicago: Callaghan. 1901: 154 [2013-09-26]. (原始內容存檔於2016-04-01).

But many held that the President's signature was not essential to an act of this kind, and, on the fourth of February, Senator Trumbull offered a resolution, which was agreed to three days later, that the approval was not required by the Constitution; "that it was contrary to the early decision of the Senate and of the Supreme Court; and that the negative of the President applying only to the ordinary cases of legislation, he had nothing to do with propositions to amend the Constitution.

- ^ Tammy Webber. Lincoln-signed copy of 13th Amendment restored. Associated Press. Boston Globe. 2011-12-06 [2013-09-26]. (原始內容存檔於2013-09-27).

- ^ Harrison, John. The Lawfulness of the Reconstruction Amendments. University of Chicago Law Review. Spring 2001, 68 (2): 390 [2013-09-26].

Those ratifications raised some tricky questions. Four of them came from organizations purporting to be the legislatures of Virginia, Louisiana, Tennessee, and Arkansas. What about them? How many states were there, how many of them had legally valid legislatures, and if there were fewer legislatures than states, did Article V require ratification by three-fourths of the states or three-fourths of the legally valid state legislatures?

- ^ 48.0 48.1 48.2 48.3 Forehand, Beverly. Striking Resemblance: Kentucky, Tennessee, Black Codes and Readjustment, 1865–1866. Masters Thesis (Western Kentucky University). 1996-05-01 [2013-09-26]. (原始內容存檔於2013-09-28).

- ^ Harrison, John. The Lawfulness of the Reconstruction Amendments. University of Chicago Law Review. Spring 2001, 68 (2): 394–397 [2013-09-26].

Then came the kicker: The President decided who was loyal, prescribing suffrage qualifications for electing the convention. [...] Pursuant to Johnson's proclamations, the provisional governors organized elections for conventions. Six met in 1865, while Texas's convention did not organize until March 1866. Three leading issues came before the convention: secession itself, the abolition of slavery, and the Confederate war debt.

- ^ Eric L. McKitrick. Andrew Johnson and Reconstruction. U. Chicago Press. 1960: 178 [2013-09-26]. ISBN 9780195057072. (原始內容存檔於2013-10-09).

- ^ Clara Mildred Thompson. Reconstruction in Georgia: economic, social, political, 1865-1872. Columbia University Press. 1915: 156 [2013-09-26]. (原始內容存檔於2013-10-09).

- ^ Vorenberg, Michael. Final Freedom: The Civil War, the Abolition of Slavery, and the Thirteenth Amendment. Cambridge University Press. 2001: 227–228 [2013-09-25]. ISBN 9781139428002. (原始內容存檔於2013-09-29).

If, by the time Congress convened in December, the amendment had been ratified with the help of southern states, Johnson's Republican opponents might think twice about denying the southern states their place in the Union. Excluding these states might come at the embarrassing price of nullifying constitutional emancipation.

- ^ DuBois, W. E. B. Black Reconstruction: An Essay Toward a History of the Part Which Black Folk Played in the Attempt to Reconstruct Democracy in America, 1860–1880. New York: Russell & Russell. 1935: 208.

Charles Sumner and others declared that [the enforcement clause] gave Congress power to enfranchise Negroes if such a step was necessary to their freedom. The South took cognizance of this argument.

- ^ McAward, Jennifer Mason. McCulloch and the Thirteenth Amendment (PDF). Columbia Law Review. 2012, 112: 1786–1787. (原始內容 (PDF)存檔於2016-01-21).

any attempt by Congress toward legislating upon the political status of former slaves, or their civil relations, would be contrary to the Constitution of the United States.

- ^ Thorpe, Francis Newton. The Constitutional History of the United States, vol. 3: 1861 – 1895. Chicago: Callaghan. 1901: 210 [2013-09-26]. (原始內容存檔於2016-04-01).

- ^ 56.0 56.1 McAward, Jennifer Mason. McCulloch and the Thirteenth Amendment (PDF). Columbia Law Review. 2012, 112. (原始內容 (PDF)存檔於2016-01-21).

- ^ DuBois, W. E. B. Black Reconstruction: An Essay Toward a History of the Part Which Black Folk Played in the Attempt to Reconstruct Democracy in America, 1860–1880. New York: Russell & Russell. 1935: 208.

(Alabama's exception:) That this amendment to the Constitution of the United States is adopted by the Legislature of Alabama with the understanding that it does not confer upon Congress the power to legislate upon the political status of freedmen in this state.

- ^ Mount, Steve. Ratification of Constitutional Amendments. 2007年1月 [2013-09-26]. (原始內容存檔於2013-06-02).

- ^ 59.0 59.1 The United States Ratifies the 13th Amendment to the Constitution. African-American Registry. [2013-09-26]. (原始內容存檔於2013年6月11日).

- ^ 60.0 60.1 60.2 The 13th Amendment: Ratification and Results. Harper Weekly. [2013-09-26]. (原始內容存檔於2013-01-15).

- ^ Harrison, John. The Lawfulness of the Reconstruction Amendments. University of Chicago Law Review. Spring 2001, 68 (2): 398 [2013-09-26].

[Seward] counted thirty-six states in all, thus rejecting the possibility that any had left the Union or been destroyed. With Georgia's action on December 6, he counted twenty-seven ratifications. So on December 18, 1865, in keeping with a duty imposed on the Secretary of State by a statute from 1818, he issued a certificate stating that Congress had proposed a constitutional amendment by the requisite two-thirds vote, that twenty-seven states had ratified, that the whole number of states in the Union was thirty-six, that twenty-seven was the requisite three-fourths majority, and that the amendment had 'be[come] valid, to all intents and purposes, as a part of the Constitution of the United States.

- ^ Andrew Kirell. Mississippi Officially Ratifies 13th Amendment Banning Slavery… 148 Years Later. Mediaite. 2013-02-18 [2013-09-26]. (原始內容存檔於2013-07-25).

- ^ 63.0 63.1 Matt Pearce. 148 years later, Mississippi ratifies amendment banning slavery. Los Angeles Times. 2013-02-18 [2013-09-26]. (原始內容存檔於2013-09-28).

- ^ Ben Waldron. Mississippi Officially Abolishes Slavery, Ratifies 13th Amendment. ABC News. 2013-02-18 [2013-09-26]. (原始內容存檔於2013-07-08).

- ^ Tsesis, Alexander. The Thirteenth Amendment and American Freedom: A Legal History. New York: New York University Press. 2004: 17, 34. ISBN 0814782760.

It rendered all clauses directly dealing with slavery null and altered the meaning of other clauses that had originally been designed to protect the institution of slavery.

- ^ 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Primary Documents in American History. the Library of Congress. [2013-09-26]. (原始內容存檔於2013-05-16).

- ^ Lowell Harrison; James C. Klotter. A New History of Kentucky. University Press of Kentucky. 1997: 180 [2013-09-26]. ISBN 9780813126210. (原始內容存檔於2013-09-27).

- ^ Hornsby, Alan (編). Delaware. Black America: A State-by-State Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO: 139. 2011 [2013-09-26]. (原始內容存檔於2013-10-09).

- ^ 69.0 69.1 69.2 69.3 69.4 Goldstone, Lawrence. Inherently Unequal: The Betrayal of Equal Rights by the Supreme Court, 1865–1903. Walker & Company. 2011 [2013-09-02]. ISBN 978-0-8027-1792-4. (原始內容存檔於2013-10-09).

- ^ 70.0 70.1 70.2 Stromberg, Joseph R. A Plain Folk Perspective on Reconstruction, State-Building, Ideology, and Economic Spoils. Journal of Libertarian Studies. Spring 2002.

- ^ Nelson, William E. The Fourteenth Amendment: From Political Principle to Judicial Doctrine. Harvard University Press. 1988: 47 [2013-09-03]. ISBN 978-0-674-04142-4. (原始內容存檔於2013-10-09).

- ^ DuBois, W. E. B. Black Reconstruction: An Essay Toward a History of the Part Which Black Folk Played in the Attempt to Reconstruct Democracy in America, 1860–1880. New York: Russell & Russell. 1935: 140.

There is a kind of innate feeling, a lingering hope among many in the South that slavery will be regalvanized in some shape or other. They tried by their laws to make a worse slavery than there was before, for the freedman has not the protection which the master from interest gave him before.

- ^ DuBois, W. E. B. Black Reconstruction: An Essay Toward a History of the Part Which Black Folk Played in the Attempt to Reconstruct Democracy in America, 1860–1880. New York: Russell & Russell. 1935: 188.

Slavery was not abolished even after the Thirteenth Amendment. There were four million freedmen and most of them on the same plantation, doing the same work that they did before emancipation, except as their work had been interrupted and changed by the upheaval of war. Moreover, they were getting about the same wages and apparently were going to be subject to slave codes modified only in name. There were among them thousands of fugitives in the camps of the soldiers or on the streets of the cities, homeless, sick, and impoverished. They had been freed practically with no land nor money, and, save in exceptional cases, without legal status, and without protection.

- ^ Vorenberg, Michael. Final Freedom: The Civil War, the Abolition of Slavery, and the Thirteenth Amendment. Cambridge University Press. 2001: 244 [2013-09-25]. ISBN 9781139428002. (原始內容存檔於2013-09-29).

Slavery was not abolished even after the Thirteenth Amendment. There were four million freedmen and most of them on the same plantation, doing the same work that they did before emancipation, except as their work had been interrupted and changed by the upheaval of war. Moreover, they were getting about the same wages and apparently were going to be subject to slave codes modified only in name. There were among them thousands of fugitives in the camps of the soldiers or on the streets of the cities, homeless, sick, and impoverished. They had been freed practically with no land nor money, and, save in exceptional cases, without legal status, and without protection.

- ^ Trelease, Allen W. White Terror: The Ku Klux Klan Conspiracy and Southern Reconstruction. New York: Harper & Row. 1971: xviii.

The truth seems to be that, after a brief exulation with the idea of freedom, Negroes realized that their position was hardly changed; they continued to live and work much as they had before.

- ^ 76.0 76.1 76.2 76.3 76.4 Blackmon, Douglas A. Slavery by Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. 2008-03-25 [2013-09-27]. ISBN 978-0-385-50625-0. (原始內容存檔於2013-10-11).

- ^ Novak, Daniel A. The Wheel of Servitude: Black Forced Labor after Slavery. University Press of Kentucky. 1978: 2. ISBN 0813113717.

- ^ Vorenberg, Michael. Final Freedom: The Civil War, the Abolition of Slavery, and the Thirteenth Amendment. Cambridge University Press. 2001: 230–231 [2013-09-25]. ISBN 9781139428002. (原始內容存檔於2013-09-29).

The black codes were a violation of freedom of contract, one of the civil rights that Republicans expected to flow from the amendment. Because South Carolina and other states anticipated that congressional Republicans would try to use the Thirteenth Amendment to outlaw the codes, they made the preemptive strike of declaring in their ratification resolutions that Congress could not use the amendment's second clause to legislate on freed people's civil rights.

- ^ Benjamin Ginsberg. Moses of South Carolina: A Jewish Scalawag during Radical Reconstruction. Johns Hopkins Press. 2010: 44–46 [2013-09-27]. (原始內容存檔於2013-10-11).

- ^ Wolff, Tobias Barrington. The Thirteenth Amendment and Slavery in the Global Economy. Columbia Law Review. 2002-05, 102 (4): 981 [2013-09-27].

Peonage was a system of forced labor that depended upon the indebtedness of a worker, rather than an actual property right in a slave, as the means of compelling work. A prospective employer would offer a laborer a "loan" or "advance" on his wages, typically as a condition of employment, and then use the newly created debt to compel the worker to remain on the job for as long as the employer wished.

- ^ 81.0 81.1 Wolff, Tobias Barrington. The Thirteenth Amendment and Slavery in the Global Economy. Columbia Law Review. 2002-05, 102 (4): 982 [2013-09-27].

Not surprisingly, employers used peonage arrangements primarily in industries that involved hazardous working conditions and very low pay. While black workers were not the exclusive victims of peonage arrangements in America, they suffered under its yoke in vastly disproportionate numbers. Along with Jim Crow laws that segregated transportation and public facilities, these laws helped to restrict the movement of freed black workers and thereby keep them in a state of poverty and vulnerability.

- ^ Wolff, Tobias Barrington. The Thirteenth Amendment and Slavery in the Global Economy. Columbia Law Review. 2002-05, 102 (4): 982 [2013-09-27].

Legally sanctioned peonage arrangements blossomed in the South following the Civil War and continued into the twentieth century. According to the Professor Jacqueline Jones, 'perhaps as many as one-third of all [sharecropping farmers] in Alabama, Mississippi, and George were being held against their will in 1900.

- ^ Wolff, Tobias Barrington. The Thirteenth Amendment and Slavery in the Global Economy. Columbia Law Review. 2002-05, 102 (4): 982 [2013-09-27].

It did not recognize a property right in a human being (a peon could not be sold in the manner of a slave); and the condition of peonage did not work 'corruption of blood' and travel to the children of the worker. Peonage, in short, was not chattel slavery. Yet the practice unquestionably reproduced many of the immediate practical realities of slavery—a vast underclass of laborers, held to their jobs by force of law and threat of imprisonment, with few if any opportunities for escape.

- ^ DuBois, W. E. B. The Freedmen's Bureau 87 (519). The Atlantic: 354–365. 1901-03 [2013-09-27]. (原始內容存檔於2012-08-31).

- ^ Tsesis, Alexander. The Thirteenth Amendment and American Freedom: A Legal History. New York: New York University Press. 2004: 50-51. ISBN 0814782760.

Blacks applied to local provost marshalls and Freedmen's Bureau for help against these child abductions, particularly in those cases where children were taken from living parents. Jack Prince asked for help when a woman bound his maternal niece. Sally Hunter requested assistance to obtain the release of her two nieces. Bureau officials finally put an end to the system of indenture in 1867.

- ^ Tsesis, Alexander. The Thirteenth Amendment and American Freedom: A Legal History. New York: New York University Press. 2004: 56-57, 60-61. ISBN 0814782760.

If the Republicans had hoped to gradually use section 2 of the Thirteenth Amendment to pass Reconstruction legislation, they would soon learn that President Johnson, using his veto power, would make increasingly more difficult the passage of any measure augmenting the power of the national government. Further, with time, even leading antislavery Republicans would become less adamant and more willing to reconcile with the South than protect the rights of the newly freed. This was clear by the time Horace Greely accepted the Democratic nomination for president in 1872 and even more when President Rutherford B. Hayes entered the Compromise of 1877, agreeing to withdraw federal troops from the South.

- ^ 87.0 87.1 87.2 87.3 87.4 87.5 87.6 Goluboff, Risa L. The Thirteenth Amendment and the Lost Origins of Civil Rights (PDF). Duke Law Journal. 2001, 50 [2013-09-27]. (原始內容存檔於2021-02-25).

- ^ Soifer, 「Prohibition of Voluntary Peonage」 (2012), p. 1617.

- ^ US Code – Title 18: Crimes and criminal procedure. Codes.lp.findlaw.com. [2013-09-27]. (原始內容存檔於2013-05-22).

- ^ 18 U.S.C. § 241: US Code – Section 241: Conspiracy against rights. Codes.lp.findlaw.com. [2013-09-27]. (原始內容存檔於2013-06-20).

If two or more persons conspire to injure, oppress, threaten, or intimidate any person in any State, Territory, Commonwealth, Possession, or District in the free exercise or enjoyment of any right or privilege secured to him by the Constitution or laws of the United States, or because of his having so exercised the same; or If two or more persons go in disguise on the highway, or on the premises of another, with intent to prevent or hinder his free exercise or enjoyment of any right or privilege so secured - They shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than ten years, or both; and if death results from the acts committed in violation of this section or if such acts include kidnapping or an attempt to kidnap, aggravated sexual abuse or an attempt to commit aggravated sexual abuse, or an attempt to kill, they shall be fined under this title or imprisoned for any term of years or for life, or both, or may be sentenced to death.

- ^ 18 U.S.C. § 242: US Code – Section 242: Deprivation of rights under color of law. Codes.lp.findlaw.com. [2013-09-27]. (原始內容存檔於2013-06-20).

Whoever, under color of any law, statute, ordinance, regulation, or custom, willfully subjects any person in any State, Territory, Commonwealth, Possession, or District to the deprivation of any rights, privileges, or immunities secured or protected by the Constitution or laws of the United States, or to different punishments, pains, or penalties, on account of such person being an alien, or by reason of his color, or race, than are prescribed for the punishment of citizens, shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than one year, or both; and if bodily injury results from the acts committed in violation of this section or if such acts include the use, attempted use, or threatened use of a dangerous weapon, explosives, or fire, shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than ten years, or both; and if death results from the acts committed in violation of this section or if such acts include kidnapping or an attempt to kidnap, aggravated sexual abuse, or an attempt to commit aggravated sexual abuse, or an attempt to kill, shall be fined under this title, or imprisoned for any term of years or for life, or both, or may be sentenced to death.

- ^ 92.0 92.1 INVOLUNTARY SERVITUDE, FORCED LABOR, and SEX TRAFFICKING STATUTES ENFORCED. U.S. Department of Justice. [2013-09-27]. (原始內容存檔於2013-07-29).

- ^ Bailey v. Alabama, 219 U.S. 219 (1911)

- ^ Specific Performance and the Thirteenth Amendment by Nathan Oman. SSRN. [2013-09-27]. (原始內容存檔於2012-09-18).

- ^ According to the Dept. of Justice, "Congress enacted § 1589 in response to the Supreme Court’s decision in United States v. Kozminski, 487 U.S. 931 (1988), which interpreted § 1584 to require the use or threatened use of physical or legal coercion. Section 1589 broadens the definition of the kinds of coercion that might result in forced labor."

- ^ Kenneth L. Karst. Thirteenth Amendment (Judicial Interpretation). Encyclopedia of the American Constitution. – 透過HighBeam Research

. 2000-01-01 [2013-09-27]. (原始內容存檔於2015-03-28).

. 2000-01-01 [2013-09-27]. (原始內容存檔於2015-03-28).

- ^ United States v Rhodes, 27 f Cas 785 (1866). Scribd. [2013-09-27]. (原始內容存檔於2013-04-02).

- ^ Seth P. Waxman. Twins at Birth: Civil Rights and the Role of the Solicitor General 75. Indiana Law Journal. 2000: 1302–1303. (原始內容存檔於2013-07-02).

- ^ Blyew v. U.S., 80 U.S. 581 (1871)

- ^ The Slaughter-House Cases, 83 U.S. 36 (1873)

- ^ United States v. Cruikshank, 92 U.S. 542 (1876)

- ^ Waskey, Andrew J. John Marshall Harlan. Wilson, Steven Harmon (編). The U.S. Justice System: An Encyclopedia: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO: 547. ISBN 978-1-59884-305-7.

- ^ Appleton's Annual Cyclopædia and Register of Important Events of the Year .... D. Appleton & Company. 1888: 132 [2013-09-27]. (原始內容存檔於2013-10-11).

- ^ Civil Rights Cases, 109 U.S. 3 (1883)

- ^ Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896)

- ^ Hodges v. United States, 203 U.S. 1 (1906)

- ^ Corrigan v. Buckley, 271 U.S. 323 (1926)

- ^ 108.0 108.1 Wolff, Tobias Barrington. The Thirteenth Amendment and Slavery in the Global Economy. Columbia Law Review. 2002-05, 102 (4) [2013-09-27].

- ^ Clyatt v. United States, 197 U.S. 207 (1905)

- ^ 110.0 110.1 Tsesis, Alexander. The Thirteenth Amendment and American Freedom: A Legal History. New York: New York University Press. 2004: 3. ISBN 0814782760.

After Reconstruction, however, a series of Supreme Court decisions substantially diminished the amendment's significance in achieving genuine liberation. The Court did not revisit the amendment's meaning until 1968, during the heyday of the Civil Rights movement. In Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer, the Court found that the Thirteenth Amendment not only ended unrecompensed, forced labor but that its second section also empowered Congress to develop legislation that is 'rationally' related to ending any remaining 'badges and incidents of servitude'.

- ^ Alison Shay. Remembering Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co.. Publishing the Long Civil Rights Movement. 2012-06-17 [2013-09-28]. (原始內容存檔於2013-09-28).

...Just as the Black Codes, enacted after the Civil War to restrict the free exercise of those rights, were substitutes for the slave system, so the exclusion of Negroes from white communities became a substitute for the Black Codes. And when racial discrimination herds men into ghettos and makes their ability to buy property turn on the color of their skin, then it too is a relic of slavery. Negro citizens, North and South, who saw in the Thirteenth Amendment a promise of freedom—freedom to 「go and come at pleasure」 and to 「buy and sell when they please」—would be left with 「a mere paper guarantee」 if Congress were powerless to assure that a dollar in the hands of a Negro will purchase the same thing as a dollar in the hands of a white man. At the very least, the freedom that Congress is empowered to secure under the Thirteenth Amendment includes the freedom to buy whatever a white man can buy, the right to live wherever a white man can live. If Congress cannot say that being a free man means at least this much, then the Thirteenth Amendment made a promise the Nation cannot keep.

- ^ Tsesis, Alexander. The Thirteenth Amendment and American Freedom: A Legal History. New York: New York University Press. 2004: 3. ISBN 0814782760.

The Court's holding in Jones enables Congress to pass statutes against present-day human rights violations, such as the trafficking of foreign workers as sex slaves and the exploitation of migrant agricultural workers as peons.

- ^ Tsesis, Alexander. The Thirteenth Amendment and American Freedom: A Legal History. New York: New York University Press. 2004: 112-113. ISBN 0814782760.

... the Thirteenth Amendment remains the principal constitutional source requiring the federal government to protect individual liberties against arbitrary private and public infringements that resemble the incidents of involuntary servitude. Moreover, the Thirteenth Amendment is a positive injunction requiring Congress to pass laws to that end, while the Fourteenth Amendment is 'responsive' to 'unconstitutional behavior.'

- ^ 韓鐵. 美国法律对劳工自由流动所加限制的历史演变——“自由资本主义阶段”之真实性质疑(三、美国劳工自由流动法律保障的逐步建立). 美國研究. 2009-02 [2013-09-28]. (原始內容存檔於2013-09-28).

- ^ Robertson v. Baldwin, 165 U.S. 275 (1897)

- ^ Selective Draft Law Cases, 245 U.S. 366 (1918); Arver v. United States, 245 U.S. 366 (1918); Grahl v. United States, Wangerin v. United States, 245 U.S. 474 (1918); Wangerin v. United States, 245 U.S. 474 (1918); Kramer v. United States, 245 U.S. 478 (1918); Graubard v. United States, 245 U.S. 366 (1918)

- ^ 117.0 117.1 United States v. Kozminski, 487 U.S. 931 (1988)

- ^ Thirteenth Amendment—Slavery and Involuntary Servitude. GPO Access. U.S. Government Printing Office: 1557. [2013-09-28]. (原始內容存檔於2013-01-14).

- ^ Risa Goluboff. The 13th Amendment and the Lost Origins of Civil Rights 50 (228). Duke Law Journal: 1609. 2001.

- ^ Loupe, Diane. Community Service: Mandatory or Voluntary? – Industry Overview. School Administrator. 2000-08: 8. (原始內容存檔於2011-07-08).

- ^ Mark W. Podvia. Titles of Nobility. David Andrew Schultz (編). Encyclopedia of the United States Constitution. Infobase: 738–739. 2009 [2013-09-28]. (原始內容存檔於2013-10-11).

- ^ 13th Amendment Site. 13thamendment.harpweek.com. [2013-09-28]. (原始內容存檔於2013-04-03).

- ^ Abraham Lincoln. First Inaugural Address of Abraham Lincoln. The Avalon Project. [2013-09-28]. (原始內容存檔於2013-06-25).

- ^ Encyclopedia of Constitutional Amendments, Proposed Amendments, and Amending ... - John R. Vile - Google Books. Books.google.com. [2013-09-28]. (原始內容存檔於2013-06-24).

擴展閱讀[編輯]

- Belz, Herman. Emancipation and Equal Rights: Politics and Constitutionalism in the Civil War Era (1978) online (頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館)

- Holzer, Harold, et al. eds. Lincoln and Freedom: Slavery, Emancipation, and the Thirteenth Amendment (2007) excerpt and text search (頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館)

- Kachun, Mitch. Festivals of Freedom: Memory and Meaning in African American Emancipation Celebrations, 1808–1915 (2003) online (頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館)

- Ripley, C. Peter et al. eds. Witness for Freedom: African American Voices on Race, Slavery, and Emancipation (1993) online (頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館)

參見[編輯]

外部連結[編輯]

- 美國國會圖書館上的第十三修正案及相關資源(頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館)

- 美國國家檔案館:第十三修正案 (頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館)

- 康乃爾大學法學院:帶註釋的憲法:第十三修正案 (頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館)

- 提議廢除奴隸制的原始文件 (頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館)

- 廢除奴隸制:由亞伯拉罕·林肯簽署的第十三修正案 (頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館),一個出售林肯簽字第十三修正案副本的經銷商網站

- 國務卿西華德宣佈修正案通過的認證文件 (頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館)

- 對1865年12月18日修正案正式宣佈通過當天法庭裁決的分析 (頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館)

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||