海湾隧道

| 海湾隧道 Transbay Tube | |

|---|---|

朝着跨湾隧道望去 | |

| 概览 | |

| 地点 | 加州旧金山湾 |

| 经纬度 | 37°48′20″N 122°21′45″W / 37.80556°N 122.36250°W坐标:37°48′20″N 122°21′45″W / 37.80556°N 122.36250°W |

| 系统 | 湾区捷运系统(BART) |

| 铁路线 | 里士满-米尔布雷线 都柏林/普莱森顿-戴利城线 |

| 起点 | 旧金山市场街地铁(内河码头站) |

| 终点 | 奥克兰奥克兰西站 |

| 车站数量 | 0 |

| 运营数据 | |

| 启用于 | 1974年 |

| 业主 | 旧金山湾区捷运系统委员会 |

| 运营单位 | 旧金山湾区捷运系统委员会 |

| 性质 | 城市轨道交通系统 |

| 技术数据 | |

| 线路长度 | 5.8 km(3.6 mi) |

| 轨道数目 | 2 |

| 轨距 | 5英尺6英寸(1,676毫米) |

| 电气化方式 | 1000 V |

| 最高海拔 | 海平面 |

| 最低海拔 | 低于海平面41米(135英尺) |

海湾隧道[1](英语:Transbay Tube),也称跨湾隧道[2],是美国旧金山湾区捷运系统的一部分,位于加州旧金山湾下方,西端衔接旧金山市中心内的市场街地铁隧道,以东则衔接至柏克莱、奥克兰(屋仑)等东湾地区。隧道长3.6英里(5.8千米),如果从隧道边最近的车站计算,长度共计6英里(10千米)。隧道在地表以下最深达到135英尺(41米)。

隧道的部件在地面组装,再由船只运至施工现场,然后沉入海底并固定(将管壁用沙砾和海床固定)。这种沉管式隧道不同于在岩层中破土前进的钻挖式隧道。

这条隧道是湾区地铁初期计划的最后一部分。[3]除里奇蒙-费利蒙线外的所有地铁线都通过这里,所以此隧道是湾区地铁里最繁忙的区间,在高峰期每小时会有2.8万人次通过[4],最短班距只有2分半。[5] 地铁在隧道里可达到最高时速80英里每小时(130千米每小时), 是均速36英里每小时(58千米每小时) 的两倍多。[6]

构想与建设[编辑]

早期构想[编辑]

最早的跨旧金山湾海底隧道的概念是由旧金山的“怪人”——自称“美利坚皇帝”的诺顿一世在1872年5月12日提出的。[7][8] 他在同年9月17日再次“下达”了这个“旨意”,还威胁要以“抗旨”为由“逮捕”奥克兰和旧金山两市的市长。[9]

这一概念被正式地提出是在1920年10月,由戈瑟尔斯少将,巴拿马运河的建造者提出。他的计划中考虑到了抗震的方面,提及了把隧道建在在湾区海底的海泥中,与今天的隧道几乎吻合。他预计的成本是50,000,000美元(相等于2022年的820,300,000美元)[10] 。不久后,在1921年7月,J. Vipond Davies和Ralph Modjeski又提出了隧道加桥梁的方案,这个方案和改良后的南部通道(从旧金山的使命岩和波卓洛角,向东至阿拉米达)很接近。两人同时指出了戈瑟尔斯将军的计划中,长距离公铁两用隧道潜在的通风问题,也暗示了仅通行电气化铁路隧道的可行性。[11]

戴维斯和莫杰斯基的计划在1921年10月加入了其他12种跨湾通道方案,其中不少也是电气铁路方案。[12][13]

1947年,一个联军委员会提议了海底隧道方案来解决已经服务了十年的海湾大桥的拥堵情况。[14] 这个建议后来在勒伯方案的可行性报告里被提出。[15][16]

建造过程[编辑]

防震方面的研究始于1959年,包括1960年的钻探和1964年的测试,以及在海床上安装的地震记录系统。由于初期研究中,受限于钻探和探测的精度,无法探明其中一块连续海床的信息,隧道被迫改道。[17]新的线路尽量避开了这块海床,使隧道可以避免弯曲压力,自由地延申。[18]

设计概念和线路调整在1960年7月完成。[19] 一份1961年的报告预估隧道的成本大概是132,720,000美元(相等于2022年的1,299,710,000美元)。[20] 施工于1965年开始,并在1969年4月3日,最后一节安放成功后完成,[21] 湾区地铁随后发行了镀铜铝制纪念币来纪念。[22] 在设施安装之前,一部分隧道在1969年9月11日向行人开放。[23]

轨道和供电在1973年完成,随后在解决了加州公共设施委员会对于供电的自动调度系统的担忧后,隧道于1974年9月16日投入服务,[24] 比计划的时间晚了5年。[25] 首次试运行在1973年8月10日,一辆自动驾驶下的列车(编号222),载着包括湾区地铁工作人员、记者和政府要员在内的100名乘客,以68—70英里每小时(109—113千米每小时)的速度,用时7分钟,从奥克兰西站开往蒙哥马利站,尔后再以80英里每小时(130千米每小时)的全速,用时6分钟返回。[26]

隧道被安放再一条宽60英尺(18米)、深2英尺(0.61米)并铺满砂砾的壕沟里。在开凿壕沟和铺砾石时,工程师从海床共凿出了5,600,000立方码(4,300,000立方米)的泥土,[27]并使用激光来校准方向,保证壕沟和砾石的误差分别小于3英寸(76毫米)和1.8英寸(46毫米) 。[28]

隧道共由57段组成,由伯利恒钢铁在70号码头的船坞制造[29][30] ,再由一条双体驳船载到海湾中间。[31] 在钢制外壳完工后,被水封的隔板也被安上并喷上水泥,形成2.3英尺(0.70米)的内壁和道床。随后,这些小节被“浮”在规划路线的上方,驳船也被拴在海床上,作为临时的牵引平台。[32] 小节都被灌入重500短吨(450公吨)的砂砾,然后再降到海床上平铺着软土、泥浆和砂砾的壕沟里。当小节到位后,潜水员会将其与其他已经到位的小节连接起来,再移除小节之间的隔板,改用沙子和碎石组成的保护层包起来。[33][31] 为了防止海水的侵蚀,隧道采用了阴极防蚀作为保护。[34]

计划共耗资1.8亿美元(相当于2016年的8.8亿美元),[35][36] 其中9000万被用于隧道的建造,其余的用于铺轨、电气化、通风和列车控制设施。[37]

配置[编辑]

隧道西端位于海湾大桥西桥脚北方,渡轮大厦附近地下,直通市区的市场街地铁,在旧金山半岛和芳草地岛之间穿过大桥的西桥,东隧道口位于奥克兰第七街,880号州际公路西侧。[38]

隧道共57小节,每节长度在273至336英尺(83至102米)之间[39],平均长达328英尺(100米),宽48英尺(15米),高24英尺(7.3米),重10,000短吨(9,100公吨)[40] 。为了保证路线,大部分小节都是笔直的,但其中有15节有水平方向的弯曲,4节有垂直方向的弯曲,2节在两个维度上都有弯曲。[39] 每节的造价将近1,500,000美元(相等于2022年的11,970,000美元),基于施工合同的90,000,000美元(相等于2022年的718,200,000美元) 总成本。[41] 外围的钢壳厚度0.625英寸(15.9毫米)[42], 刚好能承受起自重和环的压力。 一位顾问——拉尔夫·派克教授说服了项目的工程师Tom Kuesel采用薄壳,因为泥土能自然形成支持[43]。

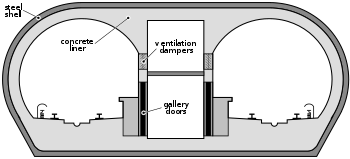

隧道由两个通道和中间的维护/行人走廊构成。每个隧道直径17英尺(5.2米), 两条隧道之间有一条走廊,其中上半部分有维护和控制设备、一条加压的消防水管、和两条条通风管道,换气速度为300,000立方英尺每分钟(8,500立方米每分钟)[44]。两条通风管可以通过远程操控的、长6英尺(1.8米)、高3英尺(0.91米)相互连通,而通风口则位于旧金山和奥克兰。两条隧道靠着走廊的两侧都有一条宽只有2.5英尺(0.76米)的步行平台[45],两侧墙壁上也各有56扇门,通往走廊的下半部分,从旧金山一侧编号依次递增,每扇间隔330英尺(100米)。通常这些门都是被锁住的,紧急时可以用工具打开。

隧道两边的出口都有一个装置[46],根据设计允许隧道有6°的偏移,换言之,隧道可以沿着隧道轴前后移动4.25英寸(108毫米),上下左右移动6.75英寸(171毫米)[47]。

防震[编辑]

隧道在内侧和外侧都有防震保护,共耗资330,000,000美元(相等于2022年的384,600,000美元)。[48]

1991年,地震发生2年后,在州政府调查委员会建议下,一份研究出台。[49]报告中指出,隧道口的防震装置“基本完好,可以抵御下一次地震”[50]。然而,地震却使隧道可偏移的幅度减少到了1.5英寸(38毫米)[51]。

事故和问题[编辑]

1979年1月火灾[编辑]

1979年1月17日约18点,一辆开往旧金山方向的7节列车(编号117)在隧道内发生电气火灾[52][53] 。一位消防员——奥克兰消防局小队长威廉·埃利奥特,50岁[54] ——因为吸入浓烟,在救火时不幸殉职。 车上的40名乘客和2名地铁工作人员随后被另一方向的列车救起[55][56] 。此次灭火行动中低效的通讯和协调,促使美国消防协会(NFPA)增加运输行业的标准(NFPA 130, 固定线路运输和乘客轨道交通系统标准)[52]。

当天早些时候,开往旧金山的363号列车在16:30,因为不明烟雾,在隧道内紧急停车。在排除故障时,驾驶员发现6节和8节车厢的防出轨条脱落,9节车厢启动了制动。随后驾驶员清理了防脱轨器的电路,解除了9节车厢的制动,并重新启动了列车。列车最后在戴利城站退出服务,作进一步检修。之后的列车都改为手动驾驶,不过很快便恢复了自动控制。其中有驾驶员报告看见363号列车遗留的零件,但是轨道没有被阻挡,依然能使用。[57]

火灾是由117号列车第5节和6节的集电靴引起的,他们撞到了前面列车落下的零件,发生了短路并起火。列车在18:06,刚刚进入隧道后停车,驾驶员报告称,列车内出现浓烟,他无法看清隧道。控制中心随后切断第三轨供电,但不到1分钟后又恢复,希望驾驶员能断开起火的车厢,然而未能成功。排气扇在08分打开,随后第三轨在15分再次断电。列车上有一名地铁管理局的高层,协助了乘客离开事发车厢。

奥克兰市消防局接到奥克兰西站的报警后,派出了2名地铁警察和9名消防员,乘坐900号列车前往现场。900号列车最后在事发车厢200英尺(61米)报告了起火车厢猛烈的火势和浓烟。在接近火场时,1名警察和7名消防员进入了逃生走廊,而其他人则因为浓烟被迫回到900号列车上。

另一边,载着千余名乘客的111号列车被扣在了旧金山一侧的内河码头站。在18:21,111号列车沿着东行隧道行驶,并接近起火车厢的位置。当所有117号列车的乘客都上车后,消防员搜索了起火列车,并在18:59向指挥部报了平安。虽然一些烟雾飘了过来,111号列车还是成功启动,随后疾驰至奥克兰西站,送乘客前往医院。同时更多消防员从奥克兰一侧进入隧道,赶赴火场。[58]但由于门被锁住,加上现场浓烟滚滚,消防员没能进入东行隧道来避难。[59]

111号列车经过的气流带倒了一些消防员,他们排成一列,开始在浓烟中,向东寻找出路。过程中,他们的防毒面具渐渐失灵,其中小队长威廉·埃利奥特无法再正常呼吸,并向队员求救。消防员再撤离火场时,又有一辆列车开来接应他们,并立即送他们会奥克兰西站,前往最近的医院。埃利奥特由于吸入过量浓烟和氰化物,不幸殉职。[60]

火虽然没有被完全扑灭,但是还是在22:45得到了控制。次日18点,奥克兰的消防员又再次前往地铁的车辆段,阻止已经面目全非的车厢里火势的扩大。[61] 湾区地铁在因隧道停运造成的1,000,000美元(相等于2022年的4,030,000美元)亏损基础上,还花费了1,100,000美元(相等于2022年的4,440,000美元)维修隧道和加强安全措施。[62]

随后,在同年的二月,湾区地铁管理局向旧金山和奥克兰消防局的局长提交了新的疏散方案,[63] 但是由于公共设施委员会主任理查德·葛拉威尔认为,“海底隧道的乘客应该意识到,地铁方面现在重开隧道,是不能提供有保障的服务的”,隧道在4月才恢复通行。[64] 两市消防局也批评湾区地铁方面没有让消防队充分掌握紧急情况的进展。[65]

地震[编辑]

作为一项预防措施,地铁的应急预案里要求,地铁在遭遇地震时应及时停车,而在海底隧道和伯克利丘隧道里的列车则应尽快前往最近的车站。随后线路会被检查,在确认安全后再恢复运营。[66]迄今最大的1989年洛马普里塔地震发生时,一辆正在隧道内的列车被下令停车,虽然驾驶员没有感受到震动。[67]地震使许多地区的公路被损坏,海湾大桥因为东桥的上桥面垮塌,也停用了一个月。相反,跨湾隧道被认为是安全的,仅6个小时后重开,12小时后地铁也恢复正常运营,[68][69]使跨湾隧道成为当时旧金山和奥克兰之间仅有的几个交通方式。[70]

行人闯入[编辑]

在2012年10月[71]和2013年8月[72],都发生过行人从内河码头站闯入隧道,逼停地铁服务的事故。在2016年12月底,又有一位行人以相同的方式闯入,并在隧道内逗留了一个小时。为了保障地铁的服务,警方一边搜寻他的下落,一边要求地铁以手动模式,低速通过隧道。[73]

设备故障[编辑]

由于设备开始老化,列车曾几次被滞留在隧道内。[74]

- 2010年3月,一辆列车的车厢突然脱钩,导致列车被迫停下。[75]

- 2014年9月,两辆维护车辆在隧道内相撞,并损坏了部分轨道,导致地铁只能使用另一侧的轨道。[76]

- 2015年1月,一辆列车的制动意外启动,使列车在隧道内停下。[77]

- 2016年12月,一辆列车出现故障,在隧道内抛锚。之后列车只能以手动模式,减速通行[78]

- 2017年4月,又有一辆列车的制动意外启动,使列车停下。

噪音[编辑]

旧金山纪事报在2010年做了一份调查,指出海底隧道是全地铁系统里噪音最大的部分,达到了100分贝,和一台电钻不相上下。[79] 噪音又因为四周的水泥墙壁,和隧道内弯曲的轨道,而非常尖锐,被形容为“女鬼的声音、尖叫的猫头鹰和《异世奇人》中失控的时光机”。[79] 2015年,地铁方面更换了6,500英尺(2,000米)、润滑了3英里(4.8千米)的轨道,有效减少了噪音,也得到了乘客的好评。[80]

海运影响[编辑]

穿行在湾区的船只,在下锚的时候,可能会损坏阴极保护层的阳离子。由于阳极是从围绕着隧道的壕沟中突出来的,他们更容易受到损坏。虽然海运部门要求了船只在经过隧道附近时不能下锚,但地铁方面还是会定期检查阳离子层的情况。[81]

2014年1月31日,由于一艘货船在早上8:45在隧道附近下锚。基于船只的位置,海岸警卫队在11:55通知了地铁管理局,认为锚离隧道非常近,隧道随后被关闭20分钟,以检查潜在的损坏。在检查过程中,两列隧道内的列车也被迫停驶,列车服务也晚点了15-20分钟。由于没有问题,隧道在12:15重新开放,并于13:00恢复正常运营。[82]码头的引航员随后记录了锚的准确位置,在隧道西南方向1,200英尺(370米)处。[83]

2017年4月,一艘为地铁方面做保护层维护的起重机船复仇者遭在夜间遇了一场冬季风暴,随后反转并沉没,船体最后停在了隧道的外壁上,万幸没有影响隧道的通行,潜水员也在次日止住了船上泄露的柴油。[84]

未来发展[编辑]

为庆祝创建50周年,湾区捷运在2007年宣布了未来50年的计划。由于隧道的运力在2030年将达到饱和,管理局构想了在旧金山湾下方建造4个隧道,于现有的隧道平行,并在南部建造跨湾换乘枢纽(已初步完工),连接加州火车和计划中的加州高铁系统。计划新建的四个隧道中,两个将提供给地铁,另外两个提供给常规/高速铁路使用,最终将有六个隧道。[85]

流行文化[编辑]

隧道当时的施工现场曾被用作乔治·卢卡斯的《五百年后》的拍摄现场,其中片尾的垂直攀爬是在尚未完工的(水平)隧道内,将镜头旋转90°拍摄的。拍摄时,隧道还没有铺设轨道,罗伯特·杜瓦尔的角色使用裸露的钢筋当作梯子。[来源请求]

由泰瑞·布鲁克斯的作品《沙纳拉》改编的电视剧《沙娜拉传奇》,部分镜头在湾区取景,其中主人公被要求穿过海底隧道。[86]

游戏《死亡空间》早期也有穿过海底隧道的剧情。[87][88]

参见[编辑]

参考文献[编辑]

- ^ BART 須知指南 (PDF). [2023-10-31]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2023-10-31).

- ^ 乘客公告板 (PDF). [2023-10-31]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2023-10-31).

- ^ Strand, Robert. San Francisco gets its space age underwater trains. The Dispatch. UPI. 14 September 1974 [20 August 2016].

- ^ The Case for a Second Transbay Transit Crossing (PDF). Bay Area Council Economic Institute: 7. February 2016 [2016-03-18]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2016-03-19).

- ^ Mallett, Zakhary. 2nd Transbay Tube needed to help keep BART on track. San Francisco Chronicle. September 7, 2014 [2018-06-19]. (原始内容存档于2018-06-12).

- ^ Minton, Torri. BART: It's not the system it set out to be. Spokane Chronicle. AP. 17 September 1984 [20 August 2016].

Hitting speeds close to 80 mph only in the 3.6-mile tube under the bay, the trains average 36 mph for safety reasons, [BART spokesman Sy] Mouber said.

- ^ Norton I. Proclamation. The Pacific Appeal. June 15, 1872: 1 [2018-06-19]. (原始内容存档于2018-06-19) –通过California Digital Newspaper Collection.

Believing Oakland Point to be the proper and only point of communication from this side of the Bay to San Francisco, we, Norton I, Dei gratia Emperor of the United State and Protector of Mexico, do hereby command the cities of Oakland and San Francisco to make an appropriation for paying the expense of a survey to determine the practicability of a tunnel under water; and if found practicable, that said tunnel be forthwith built for a railroad communication. Norton I. Given at Brooklyn the 12th day of May, 1812.

- ^ Lumea, John. Bridge Proclamations. The Emperor's Bridge Campaign. 2016 [23 July 2017]. (原始内容存档于2017年7月23日).

- ^ Norton I. Proclamation. The Pacific Appeal. September 21, 1872: 1 [2018-06-19]. (原始内容存档于2018-06-19) –通过California Digital Newspaper Collection.

Whereas, we issued our decree, ordering the citizens of San Francisco and Oakland to appropriate funds for the survey of a suspension bridge from Oakland Point via Goat Island; also for a tunnel; and to ascertain which is the best project; and whereas, the said citizens have hitherto neglected to notice our said decree; and whereas, we are determined our authority shall be fully respected; now, therefore, we do hereby command the arrest, by the army, of both the Boards of City Fathers, if they persist in neglecting our decrees. Given under our royal hand and seal, at San Francisco, this 17th day of September, 1872. NORTON 1.

- ^ San Francisco Bay Bridge Project Revived by New Plans. Engineering News-Record. 7 July 1921, 87 (1): 16–17 [8 September 2016]. (原始内容存档于2019-08-16).

Howe & Peters, consulting engineers of San Francisco, have been working for nearly two years as Pacific Coast representatives of George W. Goethals, in getting together data on the construction of a subway for both vehicular and rail traffic, which would connect the foot of Market St. with Oakland Mole. Tentative plans on this project, made public some months ago, call for a shield-driven concrete tube, similar to the type General Goethals recommended for the New York-New Jersey tube under the Hudson River.

Provision would be made for two decks, the upper for use of motor vehicles and the lower for electric trains. [...] The gradient would be kept below 3 per cent so freight could be handled easily. The depth of water along the route the tube would follow does not exceed 65 ft. and soundings taken at various points indicate that its entire length would be in blue mud. Not only would mud facilitate driving by the shield method, it is pointed out, but it would constitute a cushion to safeguard the tube from possible disalignment due to earthquake shocks.

[...]If the results of such a survey confirm the rough estimates, it is suggested that the construction of the entire 3.5-mi. concrete tube would be between $40,000,000 and $50,000,000. - ^ Features of San Francisco Bay Bridge Report. Engineering News-Record. 18 August 1921, 87 (7): 268–269 [8 September 2016]. (原始内容存档于2019-08-18).

Any high bridge between Yerba Buena Island and San Francisco would naturally land on Telegragh Hill [sic]. It would not only involve very long and costly spans, even if piers were permitted in the channel, but would land the traffic in a section of the city already quite congested, and from which a proper distribution would be impracticable. Any tunnel on this location would have to be constructed at great depth in an unknown rock formation, as the water depth is too great for tunneling under air pressure, and the length would consequently be so great as to involve an extremely difficult problem in ventilation for vehicular traffic. We there fore consider this plan as impracticable. Any continuous tunnel across the bay, on any location, while practicable for purely electrically operated railroad traffic, would involve most serious ventilation problems for vehicular traffic, and enormous expense if constructed for all classes of traffic.

- ^ Thirteen Projects Submitted for San Francisco Bay Bridge. Engineering News-Record. 3 November 1921, 87 (18): 739 [8 September 2016]. (原始内容存档于2019-08-13).

- ^ Scott, Mel. ELEVEN: Seeds of Metropolitan Regionalism. The San Francisco Bay Area: A Metropolis in Perspective Second. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. 1985: 178 [8 September 2016]. ISBN 0-520-05510-1. (原始内容存档于2019-08-15).

- ^ Bay Area Rapid Transit District. History of the Tube. Bay Area Rapid Transit District. n.d. (原始内容存档于March 29, 2013).

- ^ H.Res. 529

- ^ Report of Joint Army-Navy Board on an additional crossing of San Francisco Bay (报告). Presidio of San Francisco, California. 1947.

- ^ Aisiks, E. G.; Tarshansky, I. W. Soil Studies for Seismic Design of San Francisco Transbay Tube. Vibration Effects of Earthquakes on Soils and Foundations (ASTM STP 450). Seventy-first Annual Meeting of the American Society for Testing and Materials. San Francisco, California: American Society for Testing and Materials: 138–166. 23–28 June 1968 [7 September 2016]. (原始内容存档于2019-08-16).

- ^ Rogers, J. David; Peck, Ralph B. Engineering Geology of the Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) System, 1964-75. Geolith. 2000 [17 August 2016]. (原始内容存档于2018-11-17).

- ^ Parsons Brinckerhoff-Tudor-Bechtel. Trans-bay tube: engineering report (报告). San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit District. 1960 [7 September 2016]. (原始内容存档于2018-06-20).

- ^ Parsons Brinckerhoff-Tudor-Bechtel. Engineering Report to the San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit District (PDF) (报告). San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit District: 21. June 1961 [7 September 2016]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2019-10-15).

Use of a precast concrete tube with metal shell for the underwater crossing between shore points is recommended.

- ^ Final Section Of Transit Tube Lowered Into San Francisco Bay. Lodi News-Sentinel. UPI. 4 April 1969 [18 August 2016].

- ^ BART Tunnel Completion Moves Near. Lodi News-Sentinel. UPI. 31 March 1969 [20 August 2016].

- ^ BART Tube Is Opened For Sunday Visitors. Lodi News-Sentinel. UPI. 10 November 1969 [20 August 2016].

- ^ Leavitt, Carrick. After three year wait BART goes down the tube. Ellensburg Daily Record. UPI. 16 September 1974 [20 August 2016].

- ^ Bay Area Rapid Transit System to Open Last Link. The Times-News. AP. 27 August 1974 [20 August 2016].

- ^ Bay tube run made by BART. Lodi News-Sentinel. UPI. 11 August 1973 [20 August 2016].

- ^ Bay Tube is quake proof. Lodi News-Sentinel. UPI. 12 January 1978 [18 August 2016].

- ^ Frobenius, P.K.; Robinson, W.S. 3: Tunnel Surveys and Alignment Control. Bickel, John O.; Kuesel, Thomas R.; King, Elwyn H. (编). Tunnel Engineering Handbook Second. Norwell, Massachusetts: Kluwer Academic Publishers. 1996: 35 [20 August 2016]. ISBN 978-1-4613-8053-5. (原始内容存档于2019-08-12).

- ^ Wilson, Ralph. History of Potrero Point Shipyards and Industry. Pier 70 San Francisco. 2016 [20 August 2016]. (原始内容存档于2018-06-04).

- ^ Bethlehem built section of the BART Tubes at Pier 70. Bethlehem Shipyard Museum. 2016 [20 August 2016]. (原始内容存档于2018-06-20).

- ^ 31.0 31.1 Walker, Mark. BART—The Way to Go for the '70s. Popular Science (New York, New York: Popular Science Publishing Company). May 1971, 198 (5): 50–53; 134–135 [20 August 2016]. (原始内容存档于2019-08-16).

- ^ Gerwick Jr, Ben C. 5: Marine and Offshore Construction Equipment. Construction of Marine and Offshore Structures Third. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press. 2007: 139–140 [20 August 2016]. ISBN 978-0-8493-3052-0. (原始内容存档于2019-08-12).

- ^ BART Tunnel Completion Moves Near. Lodi News-Sentinel. UPI. 31 March 1969 [20 August 2016].

- ^ Bay Tube is quake proof. Lodi News-Sentinel. UPI. 12 January 1978 [18 August 2016].

- ^ Godfrey Jr., Kneeland A. Rapid Transit Renaissance. Civil Engineering (American Society of Civil Engineers). December 1966, 36 (12): 28–33.

- ^ Transit system safety studied. Lawrence Journal-World. AP. 23 January 1975 [17 August 2016].

- ^ Mayors open Transbay Tube. Lawrence Journal-World. AP. 20 September 1969 [17 August 2016].

- ^ Bay Tube Gets Longer. Reading Eagle. UPI. 16 December 1968 [17 August 2016].

- ^ 39.0 39.1 Frobenius, P.K.; Robinson, W.S. 3: Tunnel Surveys and Alignment Control. Bickel, John O.; Kuesel, Thomas R.; King, Elwyn H. (编). Tunnel Engineering Handbook Second. Norwell, Massachusetts: Kluwer Academic Publishers. 1996: 35 [20 August 2016]. ISBN 978-1-4613-8053-5. (原始内容存档于2019-08-12).

- ^ Final Section Of Transit Tube Lowered Into San Francisco Bay. Lodi News-Sentinel. UPI. 4 April 1969 [18 August 2016].

- ^ Exclusive Club 120 Feet Deep Offshore In San Francisco Bay. Ellensburg Daily Record. UPI. 12 March 1969 [20 August 2016].

- ^ Bender, Kristin J.; Alund, Natalie Neysa. BART: No damage after container ship's anchor drops near Transbay Tube. The Mercury News (San Jose, California). 31 January 2014 [9 September 2016]. (原始内容存档于2018-06-20).

- ^ Rogers, J. David; Peck, Ralph B. Engineering Geology of the Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) System, 1964-75. Geolith. 2000 [17 August 2016]. (原始内容存档于2018-11-17).

- ^ Bay Area Rapid Transit System. American Society of Mechanical Engineers. 24 July 1997 [17 August 2016]. (原始内容存档于2018-06-20).

- ^ Railroad Accident Report: Bay Area Rapid Transit District fire on train No. 117 and evacuation of passengers while in the Transbay Tube (PDF) (报告). National Transportation Safety Board. 19 July 1979 [17 August 2016]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2017-04-30).

|number=被忽略 (帮助) - ^ US granted 3517515,Warshaw, Robert,“Tunnel construction sliding assembly”,发表于30 June 1970,发行于17 July 1968,指定于Parsons Brinckerhoff Quade & Douglas, Inc.

- ^ Seismic retrofit for BART's Transbay tube. TunnelTalk. March 2004 [19 August 2016]. (原始内容存档于2018-06-20).

- ^ Transbay Tube Earthquake retrofit keeps farmers market in place. Bay Area Rapid Transit (新闻稿). 16 October 2006 [6 September 2016]. (原始内容存档于2018-06-21).

- ^ Housner, George W. Competing Against Time: The Governor's Board of Inquiry on the 1989 Loma Prieta Earthquake (报告). State of California, Office of Planning and Research: 19; 25; 36–37; 39. May 1990 [7 September 2016]. (原始内容存档于2019-08-12).

The impacts of the earthquake were much more than the loss of life and direct damage. The Bay Bridge is the principal transportation link between San Francisco and the East Bay. It was out of service for a [sic] over a month and caused substantial hardship as individuals and businesses accommodated themselves to its loss. [...] The most tragic impact of the earthquake was the life loss caused by the collapse of the Cypress Viaduct, while the most disruption was caused by the closure of the Bay Bridge for a month while it was repaired, leading to costly commute alternatives and probable economic losses. [...] On the other hand, the Board received reports of only very minor damage to the Golden Gate Bridge, which is founded on rock, and the BART Trans-bay Tube, which was specially engineered in the early 1960s to withstand earthquakes. [...] Two facts stand out: the importance of the Oakland–San Francisco link, and the volume of traffic borne by the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge—approximately double that of the Golden Gate Bridge, and almost equal to the combined traffic carried by all four other bridges. For automobile traffic, the Golden Gate and Bay bridges are essentially nonredundant systems, with alternative routes via the other bridges being time consuming to a level that seriously impacts commercial and institutional productivity. [...] The critical role played by the BART Trans-bay Tube in cross-bay transportation is clear, as is the fact that the South Bay bridges (San Mateo and Dumbarton) accommodated most of the redistribution of vehicular traffic. [...] Engineering studies should be instigated of the Golden Gate and San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridges, of the BART system, and of other important transportation structures throughout the State that are sufficiently detailed to reveal any possible weak links in their seimic resisting systems that could result in collapse or prolonged closure.

- ^ Parsons Brinckerhoff Quade & Douglas, Inc. Transbay Tube Seismic Joints Post-Earthquake Evaluation (报告). San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit District. November 1991.

- ^ Seismic retrofit for BART's Transbay tube. TunnelTalk. March 2004 [19 August 2016]. (原始内容存档于2018-06-20).

- ^ 52.0 52.1 3: Case Studies. Making Transportation Tunnels Safe and Secure. Washington, DC: Transportation Research Board. 2006: 42–44 [17 August 2016]. ISBN 978-0-309-09871-7. (原始内容存档于2022-04-07).

- ^ Chisholm, Daniel. 5—The Fruits of Informal Coordination. Coordination Without Hierarchy: Informal Structures in Multiorganizational Systems. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. 1992 [17 August 2016]. ISBN 9780520080379. (原始内容存档于2018-03-27).

- ^ BART train burns in tunnel; one killed. Eugene Register-Guard. AP. 18 January 1979 [17 August 2016].

- ^ Railroad Accident Report: Bay Area Rapid Transit District fire on train No. 117 and evacuation of passengers while in the Transbay Tube (PDF) (报告). National Transportation Safety Board. 19 July 1979 [17 August 2016]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2017-04-30).

|number=被忽略 (帮助) - ^ Fire shuts down BART 'tube'. Lodi News-Sentinel. UPI. 19 January 1979 [17 August 2016].

- ^ Railroad Accident Report: Bay Area Rapid Transit District fire on train No. 117 and evacuation of passengers while in the Transbay Tube (PDF) (报告). National Transportation Safety Board. 19 July 1979 [17 August 2016]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2017-04-30).

|number=被忽略 (帮助) - ^ Railroad Accident Report: Bay Area Rapid Transit District fire on train No. 117 and evacuation of passengers while in the Transbay Tube (PDF) (报告). National Transportation Safety Board. 19 July 1979 [17 August 2016]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2017-04-30).

|number=被忽略 (帮助) - ^ 3: Case Studies. Making Transportation Tunnels Safe and Secure. Washington, DC: Transportation Research Board. 2006: 42–44 [17 August 2016]. ISBN 978-0-309-09871-7. (原始内容存档于2022-04-07).

- ^ Railroad Accident Report: Bay Area Rapid Transit District fire on train No. 117 and evacuation of passengers while in the Transbay Tube (PDF) (报告). National Transportation Safety Board. 19 July 1979 [17 August 2016]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2017-04-30).

|number=被忽略 (帮助) - ^ 3: Case Studies. Making Transportation Tunnels Safe and Secure. Washington, DC: Transportation Research Board. 2006: 42–44 [17 August 2016]. ISBN 978-0-309-09871-7. (原始内容存档于2022-04-07).

- ^ BART cancels request to reopen bay tube. Lodi News-Sentinel. UPI. 12 February 1979 [20 August 2016].

- ^ BART cancels request to reopen bay tube. Lodi News-Sentinel. UPI. 12 February 1979 [20 August 2016].

- ^ BART resumes tube service for first time since fatal fire. Eugene Register-Guard. AP. 5 April 1979 [17 August 2016].

- ^ 3: Case Studies. Making Transportation Tunnels Safe and Secure. Washington, DC: Transportation Research Board. 2006: 42–44 [17 August 2016]. ISBN 978-0-309-09871-7. (原始内容存档于2022-04-07).

- ^ BART to participate in statewide earthquake drill Thursday (新闻稿). San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit District. 14 October 2015 [7 September 2016]. (原始内容存档于2018-06-21).

- ^ Jordan, Melissa. Behind the Scenes of BART's Role as Lifeline for the Bay Area. San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit District. 2014 [7 September 2016]. (原始内容存档于2018-06-12).

Donna "Lulu" Wilkinson, an experienced train operator, was barreling through the Transbay Tube at 80 miles per hour in the cab of a 10-car train when the quake hit.

"I didn't even feel it," she recalled. She was about halfway through to San Francisco when she got the order to stop and hold her position.

It was routine procedure (and remains so) to do a short hold after any earthquake, even smaller ones, and passengers were familiar with that routine. "They didn't panic," she said. "I got on the intercom and told them we were holding for a quake and would be moving shortly."

The design and strength of the tube, an engineering marvel sunk into mud on the bottom of the bay, had insulated the train and its passengers from feeling the earth's movements. - ^ Jordan, Melissa. Behind the Scenes of BART's Role as Lifeline for the Bay Area. San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit District. 2014 [7 September 2016]. (原始内容存档于2018-06-12).

Donna "Lulu" Wilkinson, an experienced train operator, was barreling through the Transbay Tube at 80 miles per hour in the cab of a 10-car train when the quake hit.

"I didn't even feel it," she recalled. She was about halfway through to San Francisco when she got the order to stop and hold her position.

It was routine procedure (and remains so) to do a short hold after any earthquake, even smaller ones, and passengers were familiar with that routine. "They didn't panic," she said. "I got on the intercom and told them we were holding for a quake and would be moving shortly."

The design and strength of the tube, an engineering marvel sunk into mud on the bottom of the bay, had insulated the train and its passengers from feeling the earth's movements. - ^ Annex to 2010 Association of Bay Area Governments Local Hazard Mitigation Plan "Taming Natural Disasters" (PDF) (报告). Association of Bay Area Governments: 8. 2010 [7 September 2016]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2018-11-30).

BART's success in maintaining continuous service directly after the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake reconfirmed the system's importance as a transportation "lifeline." While the earthquake caused transient movements in the Tube there was no significant permanent movement and BART service was uninterrupted except for a short inspection period immediately following the quake. With the closure of the Bay Bridge and the Cypress Street Viaduct along the Nimitz Freeway, BART became the primary passenger transportation link between San Francisco and East Bay communities. Its average daily transport of 218,000 passengers before the earthquake increased to an average of 308,000 passengers per day during the first full business week following the earthquake.

- ^ Housner, George W. Competing Against Time: The Governor's Board of Inquiry on the 1989 Loma Prieta Earthquake (报告). State of California, Office of Planning and Research: 19; 25; 36–37; 39. May 1990 [7 September 2016]. (原始内容存档于2019-08-12).

The impacts of the earthquake were much more than the loss of life and direct damage. The Bay Bridge is the principal transportation link between San Francisco and the East Bay. It was out of service for a [sic] over a month and caused substantial hardship as individuals and businesses accommodated themselves to its loss. [...] The most tragic impact of the earthquake was the life loss caused by the collapse of the Cypress Viaduct, while the most disruption was caused by the closure of the Bay Bridge for a month while it was repaired, leading to costly commute alternatives and probable economic losses. [...] On the other hand, the Board received reports of only very minor damage to the Golden Gate Bridge, which is founded on rock, and the BART Trans-bay Tube, which was specially engineered in the early 1960s to withstand earthquakes. [...] Two facts stand out: the importance of the Oakland–San Francisco link, and the volume of traffic borne by the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge—approximately double that of the Golden Gate Bridge, and almost equal to the combined traffic carried by all four other bridges. For automobile traffic, the Golden Gate and Bay bridges are essentially nonredundant systems, with alternative routes via the other bridges being time consuming to a level that seriously impacts commercial and institutional productivity. [...] The critical role played by the BART Trans-bay Tube in cross-bay transportation is clear, as is the fact that the South Bay bridges (San Mateo and Dumbarton) accommodated most of the redistribution of vehicular traffic. [...] Engineering studies should be instigated of the Golden Gate and San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridges, of the BART system, and of other important transportation structures throughout the State that are sufficiently detailed to reveal any possible weak links in their seimic resisting systems that could result in collapse or prolonged closure.

- ^ Man Walking In Transbay Tube Prompts Temporary BART Shutdown. CBS SFBayArea. 15 October 2012 [17 August 2016]. (原始内容存档于2018-06-20).

- ^ Alund, Natalie Neysa. BART trains back on track after man found walking in Transbay Tube. Oakland Tribune. 11 August 2013 [18 August 2016].

- ^ Bodley, Michael. Man who sparked BART delays by running into Transbay Tube IDd. San Francisco Chronicle. 30 December 2016 [13 April 2017]. (原始内容存档于2018-06-20).

- ^ Cabanatuan, Michael; Veklerov, Kimberly; Ravani, Sarah. BART systemwide meltdown after train gets stuck in West Oakland. San Francisco Chronicle. 6 January 2017 [13 April 2017]. (原始内容存档于2018-06-12).

- ^ Lee, Henry K. BART train splits in two in Transbay Tube. San Francisco Chronicle. 17 March 2010 [13 April 2017]. (原始内容存档于2018-06-20).

- ^ Kane, Will; Huet, Ellen; Lee, Henry K. BART reopens Transbay Tube track. San Francisco Chronicle. 3 September 2014 [13 April 2017]. (原始内容存档于2018-06-20).

- ^ Williams, Kale. BART delays again after train gets stuck in Transbay Tube. San Francisco Chronicle. 7 January 2015 [13 April 2017]. (原始内容存档于2018-06-20).

- ^ Veklerov, Kimberly. Train stuck in Transbay Tube causes major BART delays. San Francisco Chronicle. 20 December 2016 [13 April 2017]. (原始内容存档于2018-06-20).

- ^ 79.0 79.1 Cabanatuan, Michael. Noise on BART: How bad is it and is it harmful?. SFGate. 2010-09-07 [2016-04-22]. (原始内容存档于2016-05-01).

- ^ Riders notice a quieter ride following first of two tube shutdowns. www.bart.gov. 2015-08-13 [2016-04-22]. (原始内容存档于2016-05-07).

- ^ Reisman, Will. BART working to protect Transbay Tube from elements, ships. San Francisco Examiner. 12 May 2013 [9 September 2016]. (原始内容存档于2018-06-21).

- ^ Bender, Kristin J.; Alund, Natalie Neysa. BART: No damage after container ship's anchor drops near Transbay Tube. The Mercury News (San Jose, California). 31 January 2014 [9 September 2016]. (原始内容存档于2018-06-20).

- ^ Williams, Kale; Ho, Vivian. BART tube reopened after anchor scare. San Francisco Chronicle. 1 February 2014 [9 September 2016]. (原始内容存档于2018-06-21).

- ^ Close eye being kept on sunken barge atop BART's Transbay Tube. San Francisco Examiner. Bay City News. 11 April 2017 [13 April 2017]. (原始内容存档于2018-06-21).

- ^ Cabanatuan, Michael. BART's New Vision: More, Bigger, Faster. San Francisco Chronicle. 2007-06-22: A–1 [2008-04-17]. (原始内容存档于2007-10-10).

- ^ Dowd, Katie. MTV show uses BART's Transbay Tube as the key to saving the world. San Francisco Chronicle. 10 March 2016 [17 August 2016]. (原始内容存档于2018-06-21).

- ^ Veca, Don (audio director); Napolitano, Jayson (interviewer). Dead Space sound design: In space no one can hear interns scream. They are dead. (访谈). Original Sound Version. 7 October 2008 [18 August 2016]. (原始内容存档于2018-06-21).

- ^ YouTube上的Dead Space Dev Diary #3 -- Audio (starts at 4:30)

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||