動物

| 動物界 化石時期:成冰紀至今,

| |

|---|---|

| |

| 科學分類 | |

| 域: | 真核域 Eukaryota |

| 演化支: | 單鞭毛生物 Amorphea |

| 演化支: | OBA 超類群 Obazoa |

| 演化支: | 後鞭毛生物 Opisthokonta |

| 總界: | 動物總界 Holozoa |

| 演化支: | 蜷絲動物 Filozoa |

| 演化支: | 領鞭毛動物 Choanozoa |

| 界: | 動物界 Animalia Linnaeus, 1758 |

| 門 | |

| 異名 | |

| |

動物(英語:animal)或稱後生動物(學名:Metazoan),是一群具有自主運動性的多細胞真核生物,在生物分類學上構成名為動物界(Animalia)的分類階層,與植物、真菌和原生生物一起構成了真核生物域下的四大界。

動物主要分多孔動物、刺胞動物、櫛板動物、扁盤動物和兩側對稱動物五大總門。多數通俗意義上的現存動物物種都屬於兩側對稱動物,身體結構至少在胚胎發育時期會沿着縱軸正中矢狀面呈現左右對稱,其中最為突出的是原口動物和後口動物兩大演化支,前者包括大部分無脊椎動物,如節肢動物、軟體動物、環節動物、扁形動物等,其中前兩者的物種多樣性最為繁盛;後者則包括了棘皮動物、半索動物和脊索動物,其中最為成功的是脊索動物下的脊椎動物(有頭類)。除了少數與藻類形成共生的特例外,絕大多數動物是異養生物,必須從別處覓食攝取有機物來滿足代謝需求,除少數物種外都必須呼吸氧氣滿足細胞呼吸,具有一定移動性和一定程度特化的肌肉細胞,依賴有性生殖進行繁衍,而且其胚胎發育過程從空心細胞球(囊胚)開始。動物個體的全長從8.5×10−6到33.6米不等。它們與其棲息環境、生態位和與其它生物之間的關係有着複雜的相互作用,形成了繁雜的食物網。

在元古宙後期的拉伸紀晚期,多細胞生物終於結束了「無聊十億年」的硫化缺氧窘境,出現了以原始海綿為代表的最早的動物生命形式。在成冰紀的雪球地球事件後,早期動物在埃迪卡拉紀出現了第一次演化輻射——阿瓦隆大爆發。所有現存動物共有的6331個基因組已經被確認,這些基因可能來自6.5億年前的一個前寒武紀的共同祖先。在埃迪卡拉紀末滅絕事件之後,大約5.42億年前開始的寒武紀大爆發在較短期內出現了許多具有礦化組織和快速運動能力的海洋生物,就化石記錄來看大多數現代動物所在的門都演化自這些寒武紀生物。這些早期動物的後裔在之後的5.4億年間經歷了五次大規模的和不計其數的中小型滅絕事件,只有約千分之一的物種延續至今,其餘全部滅絕消亡。目前已有逾150萬個現生動物物種被發現和命名,其中多樣性最豐富的類群是節肢動物門下的昆蟲綱,約有100萬種。

分類史上,亞里士多德將動物分為「有血液的」和「無血液的」。1758年,瑞典生物學家卡爾·林奈在其所著《自然系統》一書中創建了第一個動物分類系統。1809年,讓-巴蒂斯特·拉馬克將其擴展到14個門級分類單元。1874年,恩斯特·海克爾將動物界分為多細胞後生動物(動物的異名)和原生動物,單細胞生物不再被視為動物。在現代,動物的生物學分類依賴分子系統發生學等先進分析技術,能夠有效地證明動物分類單元之間的演化關係。

在人類發展的過程中,動物產品(肉、蛋和奶)一直是重要的食物來源,源自其它動物的皮、毛、羽和脂肪則被用作保溫材料、取暖照明的燃料以及減少機械材料損蝕的潤滑劑和防鏽劑,動物骨骼、牙齒和犄角在石器時代還曾被用來製作漁具、武器和建築材料,甚至在農業革命後的信史時期仍被用作裝飾品。一些動物則更是被馴化成為家禽、家畜或寵物,為人類提供穩定可控的養殖產能和技能服務。除此之外,各種動物概念的圖騰也是人類文化(如藝術、神話、宗教和政治)的重要組成部分。

詞源[編輯]

動物界的學名「Animalia」源自於拉丁文「animalis」,意指「會呼吸的」、「具有靈魂」[1]。生物學上的定義含括動物界的所有成員[2]。在口語上則因受到人類中心主義影響,常僅指稱人類以外的其他動物[3][4][5][6]。

特徵[編輯]

動物界的所有成員皆屬於多細胞真核生物[7][8]。本界絕大多數物種屬於異營生物[8][9][10],少部分可進行無氧呼吸[11],有別於具有光自營性的植物及藻類[12]。動物在其生命周期的某個階段具有自主活動的能力[13]。海綿、珊瑚、淡菜及藤壺等動物在幼體時期具有活動能力,但會逐漸失去活動力,成為固著生物。大多數動物的胚胎發育過程中具有囊胚期,此階段為動物獨有的時期[14]。在囊胚期,細胞會分化為不同的組織及器官[15]。

結構[編輯]

所有動物皆由細胞所構成,有些細胞外面還有膠原蛋白和醣蛋白所構成的胞外基質被覆[16]。在動物個體發育時,胞外基質的可塑性會提升,使細胞易於移動及重組,讓細胞可以形成複雜的構造。胞外基質也可能透過鈣化或礦化作用,形成外殼、骨架、骨針及等構造[17]。真菌、植物及藻類等多細胞生物的細胞外則擁有相對堅固的細胞壁,導致其細胞的活動能力有限,因此成長緩慢[18]。此外,動物細胞之間擁有特別的細胞連結構造,例如緊密連接、間隙連接及胞橋小體等等[19]。

除了多孔動物門及扁盤動物門這些基群以外,動物體擁有許多不同的特化組織[20],如肌肉組織及神經組織等等,可以輔助個體進行運動及體內信號傳遞。一般來說,動物體也會擁有消化腔,而消化腔又可分為兩種,一種是只有一個開口的囊狀消化系統,如櫛板動物門、刺胞動物門及扁形動物門等採取的就是這種模式;另一種是擁有兩個開口的管狀消化系統,大多數兩側對稱動物的消化道屬於此類[21]。

繁殖與發育[編輯]

幾乎所有的動物都通過有性生殖進行繁殖活動[22]。它們可以通過減數分裂產生單倍體配子;體積小、能自由運動的配子為精子,體積大、不能自由運動的為卵子[23],兩者合二為一會形成受精卵[24],隨後有絲分裂為中空的球狀物體——囊胚。海綿的囊胚幼蟲會游到新地點,將自己固定在海床上,並發育為新的海綿[25]。其他大多數動物的幼體則會經歷更為複雜的過程[26],先內陷成原腸胚,發育出消化室以及內、外兩個相互分離的胚層[27]。在絕大多數情況下,這兩個胚層之間還會發育出第三個胚層——中胚層[28]。隨後這些胚層分化為不同的組織、器官[29]。

反覆近親繁殖會導致隱性的缺陷基因盛行率增加,進而導致近交衰退現象[30][31]。為了避免此種情形,動物演化出了多種避免近交的機制[32]。例如輝藍細尾鷯鶯的雌鳥會與多隻公鳥交配,提升後代的基因多樣性[33]。當然動物也有遠交衰退現象[34]。

有些動物能進行無性生殖,此類的動物基因會與親本完全相同。無性生殖的方式包含斷裂生殖、出芽生殖(如水螅等刺胞動物)和單性生殖(如可在未交配的情形下自行產生受精卵的蚜蟲)[35][36]。

生態學[編輯]

依據攝入與消耗有機質的形式,動物可分作數個不同的生態類群:肉食動物、植食動物、雜食動物、食腐動物/食碎屑動物[37]以及寄生動物[38],不同類群動物間的互動形成複雜的食物網。肉食動物與雜食動物具有捕食行為,為一種消費者-資源相互作用,指的是這些動物以其他動物(稱為獵物)為食[39]。捕食的行為也導致了掠食者與獵物之間的演化軍備競賽,使獵物產生反捕食者適應[40][41]。多細胞掠食者幾乎都是動物[42]。部分消費者的食性不止一種,例如寄生蜂的幼蟲就主要以寄主的身體組織為食,並最終殺死寄主[43];但成蟲則主要以花蜜為食[44]。其他動物的進食行為可以非常專一,例如玳瑁就幾乎只食用海綿[45]。

大多數的動物仰賴植物光合作用所產生的生物質與能量,其中草食動物會直接取食植物,而位於較高營養級的肉食動物則透過食用其他動物獲得能量。動物必須透過氧化醣類、脂類及蛋白質等生物分子獲取氧分子的化學能[46],這些能量能協助動物成長並維持必要的生物過程(如運動)[47][48][49]。棲息於深海海床上的海底熱泉及冷泉附近的動物則仰賴能進行化能合成(透過氧化無機物,如硫化氫等來獲得能量)的古菌與細菌維生[50]。

動物最早起源於海洋,節肢動物與有胚植物約同時於芙蓉世至奧陶紀早期(5.10億-4.71億年前)登陸[51]。脊椎動物,例如肉鰭魚綱的提塔利克魚屬,則約於3.75億年前的泥盆紀晚期登陸[52][53]。現存動物幾乎可在地球上的任何棲息地與微棲息地中被發現,包括鹹水、海底熱泉、淡水、溫泉、沼澤、森林、草原、沙漠、空中,甚至是其他動物、植物、真菌體內或岩石內[54]。然而動物並非嗜熱生物,僅有極少數物種能適應超過50 °C(122 °F)的高溫[55]。此外,也僅有極少數物種(多為線蟲)能棲息於南極洲極低溫的寒漠之中[56]。水熊蟲甚至能在外太空生活,直到太陽照射。

多樣性[編輯]

體型[編輯]

藍鯨是地球上存在過的最大的動物,重可近200公噸(200長噸;220短噸),長33公尺(108英尺)[57][58][59],現存最大的陸生動物是非洲草原象,重可達12.25公噸(12.06長噸;13.50短噸)[57],體長10.67公尺(35.0英尺)[57]。不過實際上地球上還存在過比非洲草原象更大的陸生動物。蜥腳下目的阿根廷龍屬恐龍最重可達73公噸(72長噸;80短噸)[60]。 相對的,一些黏體動物(刺胞動物門的專性寄生物)最大也超不過20微米[61],其中最小的碘泡蟲在成年時體長甚至不到8.5微米[62]。

數量與分布[編輯]

以下列出現存物種數量最多的幾個動物門[63]以及它們的棲息地和生活習性[64][65][66]。下表的數據是基於人們迄今為止描述過的物種數量的估算,但實際數量因各文獻採用的不同估算方法而有很大出入。例如,雖然現在科學家已描述了25,000至27,000種線蟲類生物,但線蟲的實際數量目前仍未有定論,估測實際數量有1萬-2萬、50萬、1000萬甚至1億不等。[67]。截至2011年[update],依照生物分類結構所展示出來的規律,人們估算地球上可能共有777萬種動物[68][69][a]。

| 門 | 圖例 | 物種 數量 |

陸地 | 海洋 | 淡水 | 自由 活動 |

寄生 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 環節動物 |

|

17,000[63] | 是(分布於土壤中)[65] | 是[65] | 1,750[64] | 是 | 400[66] |

| 節肢動物 |

|

1,257,000[63] | 1,000,000 (昆蟲綱)[73] |

>40,000 (軟甲綱)[74] |

94,000[64] | 是[65] | >45,000[b][66] |

| 外肛動物 |

|

6,000[63] | 是[65] | 60–80[64] | 是 | ||

| 脊索動物 |

|

66,000[63][75] 45,000[76] |

33,278[75] 23,000[76] |

13,000[76] |

18,000[64] 9,000[76] |

是 | 40(部分鯰形目)[77][66] |

| 刺胞動物 |

|

16,000[63] | 是[65] | 是(少數物種)[65] | 是[65] | >1,350 (黏體動物)[66] | |

| 棘皮動物 |

|

7,500[63] | 7,500[63] | 是[65] | |||

| 軟體動物 |

|

85,000[63] 107,000[78] |

35,000[78] |

60,000[78] |

5,000[64] 12,000[78] |

是[65] | >5,600[66] |

| 線蟲動物 |

|

25,000[63] | 是(分布於土壤中)[65] | 4,000[67] | 2,000[64] | 11,000[67] | 14,000[67] |

| 扁形動物 |

|

29,500[63] | 是[79] | 是[65] | 1,300[64] | 是[65] 3,000–6,500[80] |

>40,000[66] 4,000–25,000[80] |

| 輪形動物 |

|

2,000[63] | >400[81] | 2,000[64] | 是 | ||

| 多孔動物 |

|

10,800[63] | 是[65] | 200-300[64] | 是 | 是[82] | |

| 已描述的動物物種數量總計(2013年): 1,525,728[63] | |||||||

起源和化石記錄[編輯]

已知最早的動物化石出土於南澳大利亞州特雷佐納組6.65億年前的岩層,一般認為這些化石是當代多孔動物門的雛形[84]。

而已知最早的動物化石集群出現在前寒武紀末期的埃迪卡拉生物群(5.80億至5.42億年前)。對於埃迪卡拉生物群是否屬於動物長期存在著爭議[85][86][87],直到狄更遜水母化石中所發現的動物性脂質膽固醇證明了牠們確實屬於動物[83]。科學家認為動物起源於低含氧量的環境,且能夠進行無氧呼吸,但它們之後逐漸演化為有氧呼吸生物,需要環境中的氧氣來維持生存[88]。

許多動物門類的化石紀錄出土於寒武紀大爆發的岩層,這段時期從5.42億年前開始,並持續了2500萬年左右[89]。其中,加拿大的伯吉斯頁岩及中國的澂江化石地是著名的化石發現地點,此二地出土的動物化石包含軟體動物門、腕足動物門、有爪動物門、鰓曳動物門、緩步動物門、節肢動物門、棘皮動物門與半索動物門等類群,亦有如古杯動物、古蟲動物和三葉蟲等已滅絕的動物。不過「大爆發」也有可能僅僅代表化石產地有大量的化石產出,而非大部分的動物均於同一時間演化出現[90][91][92][93]。

部分古生物學家認為動物在10億年前就已出現,遠遠早於寒武紀大爆發年代[94]。於拉伸紀地層發現的爬行痕跡與地穴的遺蹟化石顯示,當時可能存在有三胚層的蠕蟲型動物,寬度為5公釐(0.20英寸),外型約近似於現存的蚯蚓[95]。然而,現今的巨型單細胞原生生物圓球網足蟲也能產生類似的痕跡,因此拉伸紀的化石痕跡很可能與早期的動物演化無關[96][97]。科學家約於同一地層年代發現了一些化石證據,或可證明食草動物的出現——由微生物菌落堆疊而成的疊層石的種類減少,可能是動物的牧食造成的[98]。

系統發育學[編輯]

動物界是一個單系群,有着共同的祖先。它和領鞭毛蟲有親緣關係,都屬於聚胞動物[99]。其基群為多孔動物門、櫛板動物門、刺胞動物門和扁盤動物門,這些門類的動物身體左右不對稱。這些分類之間的關係還存在爭議——多孔動物門或櫛板動物門可能是所有其他動物分類的姐妹群,它們都缺乏身體構造形成中重要的Hox基因[100]。這些基因在扁盤動物門[101][102]和更高等的兩側對稱動物體內均有出現[103][104]。

現已發現有6331組現存動物共同的基因,這些基因可能全部出自6.5億年前的一個共同祖先。其中有25組是核心基因組,僅見於動物體內,當中有8組與Wnt和TGF-β訊息傳遞路徑相關,這些信息傳導途徑可以影響生物體的體軸發育,很可能是動物體能從單細胞生物脫胎成為多細胞生物的關鍵。另外還有7組為同源框蛋白等發育調控蛋白的轉錄因子[105][106]。

以下列出主要演化支的系統發生樹,並給出由分子鐘推測的各支分化大概年份[107][108][109][110][111]。

| 聚胞動物 |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 9.5億年前 |

非兩側對稱[編輯]

非兩側對稱動物描述的是缺乏兩側對稱性的動物類群,包含多孔動物門(如海綿等)、櫛板動物門(櫛水母)、扁盤動物門(如絲盤蟲等)[112][113],以及刺胞動物門(如水母、海葵及珊瑚等)等等。多孔動物門缺乏其他絕大多數動物門所具有的複雜器官或系統[114],雖然海綿的細胞有分化現象,但未形成組織和器官[115]。海綿大多依靠海水流過體表的小孔來獲得食物和氧氣,並排除廢物[116]。櫛板動物門和刺胞動物門解剖上呈輻射對稱,因此早期的文獻稱其為輻射對稱動物(Radiata)[117],但近年來的文獻已較少使用。這兩個門的動物具有分化的組織,但尚未形成器官[118]。它們屬於雙胚層動物,僅具有外胚層與內胚層,不具有中胚層[119]。體型較小的扁盤動物情況類似,但它們沒有永久性的消化腔[112][113]。

傳統的生物學認為,原始的動物缺乏對稱性,因此認為無對稱性的多孔動物門是最古老的演化支[117][120]。其後出現的是輻射對稱動物,之後才發展出兩側對稱動物[117]。然而,這樣的觀點在近年來卻不斷受到挑戰[121]。有些學者根據分子遺傳研究,認為櫛板動物門才是最基群的動物演化支[121][122]。若然如此,動物對稱性的起源將比傳統認知的更加複雜,代表海綿喪失對稱性是次級性的[121]。目前兩個假說之間的爭論仍持續當中。

兩側對稱[編輯]

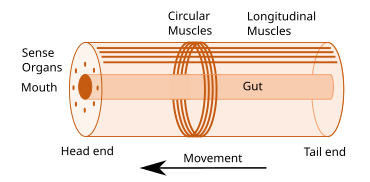

剩下的是占絕大多數的兩側對稱動物,其下共計28個門,擁有超過100萬個物種。其身體有三胚層,組織可分化為不同的器官。消化室有口、肛兩個開口,其中部則發育為體腔或假體腔。這些具有兩側對稱身體模式、傾向於朝特定方向運動的動物可以區分前端(頭部)、後端(尾部),以及背側、腹側,因此也有左右兩側之分[123][124]。

動物的前端可以受到食物等外部刺激,並由此產生頭部專化現象,演化出長有感官、口的頭部。許多兩側對稱動物擁有環繞身軀的肌肉群,可用來束縛身體;以及與之交錯的縱向肌群,可縮短體型[124]。這些肌群使得長有靜水骨骼的軟體動物以蠕動的方式來移動[125]。它們的消化道從口部沿着柱狀的身軀一直通向肛門。兩側對稱動物有不少門的初期幼蟲可利用纖毛四處游動,其頂器長有感覺細胞。不過,這些規律也有些偶發的意外,比如成年棘皮動物體型呈輻射對稱,和其幼體大相徑庭;一些寄生蟲的身體結構則極為簡單[123][124]。

基因學研究扭轉了動物學家對各兩側對稱動物之間關係的認知,大部分轉變集中在原口動物和後口動物這兩個大演化支上[126]。通過基因分析,人們還了解到異無腔動物是兩側對稱動物的基群[127][128][129]。

原口動物和後口動物[編輯]

在剛開始發育時,後口動物的囊胚會進行輻射卵裂,而大多數的原口動物(又稱螺旋動物)則進行螺旋卵裂(又稱不定卵裂)[130]。原口動物與後口動物均有完整的消化道,但原口動物原腸最初的胚孔最後會發育為口,之後另一端才會形成肛門;而後口動物最初的胚孔則是發育為肛門,之後另一端發展為口,也因此得名[131][132]。大多數的原口動物透過裂體腔法形成中胚層與體腔,於原口兩側,內胚層與外胚層的交界處會有細胞分裂深入到內外胚層之間,這些細胞稱為中胚層細胞,發展為中胚層後在中胚層之間的空腔即稱為體腔。後口動物則透過腸體腔法形成中胚層,由內胚層兩側的細胞內凹,形成成對的腔腸囊,和內胚層脫離後,在內外胚層之間的腔腸囊就會發展為中胚層[133]。

棘皮動物門和脊索動物門為後口動物[134],棘皮動物門只在水中生活,包括海星、海膽與海參[135]。脊索動物門中大多動物為脊椎動物[136],包括魚類、兩棲動物、爬行動物、鳥類及哺乳動物[137]。其他後口動物則包括半索動物門[138][139]。

蛻皮動物[編輯]

蛻皮動物是原口動物,一如其名,牠們必須透過蛻皮成長[140]。蛻皮動物包括了最大的動物門節肢動物門,包括昆蟲、蜘蛛、螃蟹等,這些動物的身體均有分節,且多具有成對的附肢。另外兩個較小的門,有爪動物門及緩步動物門,為節肢動物的近親並具有相似的特徵。蛻皮動物也包括線蟲動物門,可能為第二大的動物門。線蟲多半僅可於顯微鏡下可見,棲息於幾乎所有含水的生態系[141],部分物種為常見的寄生蟲[142]。線蟲動物門的近親包括線形蟲動物門、動吻動物門、鰓曳動物門及鎧甲動物門。線蟲與這些近親物種的體腔不具有體腔膜,又稱為假體腔[143]。

螺旋動物[編輯]

螺旋動物是原口動物下的一個大類,在胚胎早期階段以「螺旋式」卵裂進行發育[144]。關於螺旋動物的系統發育仍存在一定爭議,但目前認為它包含了一個大演化支——冠輪動物總門,以及一些更小的門,如扁蟲動物(包括腹毛動物和扁形動物)。這些分類都屬於扁蟲冠輪動物。扁蟲冠輪動物擁有姐妹群有顎動物,該分類下包含輪形動物[145][146]。

冠輪動物下屬的分類有軟體動物門、環節動物門、腕足動物門、紐形動物門、外肛動物門和內肛動物門[145][147][148]。其中,軟體動物門是動物界的第二大門,包括蝸牛、蛤蜊及管魷等,而環節動物則由分節動物組成,包括蚯蚓、沙蠋及螞蟥等。這兩組動物被認為是近親,因為它們在幼蟲階段都呈現擔輪幼蟲的形態[149][150]。

分類史[編輯]

在古典時代,亞里士多德在《動物志》和《論動物的組成》中把動物分為有血的(脊椎動物一般有血)和沒有血的。然後將動物通過一種分類尺度進行排列,從人(有血液,兩足,理性靈魂)向下到有生命的四肢動物(有血液,四足,感性靈魂)再到其它分類群如甲殼類動物(無血,多足,感性靈魂)再向下到像海綿那樣自然發生的生物(無血,無腿,植物靈魂)。亞里士多德不能確定海綿是否是動物,在他的分類系統中動物應該有感覺、食慾、能運動,而植物就沒有:他知道海綿可以感應到觸摸,如果將其從所在的岩石上拉下來時它就會收縮,但它們像植物那樣會紮根,不會來回移動[152]。

在1758年,卡爾·林奈在他的《自然系統》創建了第一個分級分類[153]。在他一開始的計劃中,動物是三個域中的一個,分為蠕蟲類、昆蟲類、魚類、兩棲類、鳥類和哺乳類。後來,人們將後四種都被歸入脊索動物門一個門,而昆蟲類(包括甲殼類和蛛型動物)和蠕蟲類都被重新命名或再細分。讓-巴蒂斯特·拉馬克在1793年開始將動物重新分類,他稱蠕蟲類「非常混亂」(法語:une espèce de chaos[d]),將其拆成三個新門類:蠕蟲類、棘皮類和水螅類(包含珊瑚和水母)。1809年,拉馬克在《動物哲學》中將動物分為11類:脊椎動物(這部分他仍然下分為4類:哺乳類、鳥類、爬行類和魚類)、軟體動物、蔓足類、環節動物類、甲殼類、蛛型類、昆蟲類、蠕蟲類、放射蟲類、水螅類和纖毛蟲類[151]。

在喬治·居維葉於1817年所著的《動物界》裡,他從比較解剖學的角度將動物分為四個分支(embranchements,其有不同的形態學所有體型,大致相當於門),即脊椎動物、軟體動物、有絞動物(節肢動物和環節動物)和植物型動物(居維葉稱作「放射蟲」,包含棘皮動物、刺胞動物和其它形式)[155]。這種劃分成四類的方式後來得到過胚胎學家卡爾·恩斯特·馮·貝爾(1828年)、動物學家路易斯·阿加西(1857年)和比較解剖學家理查德·歐文(在1860年)的完善[156]。

1874年,恩斯特·海克爾將動物界分為兩個亞界:後生動物(多細胞動物,有五個門類:腔腸動物、棘皮動物、有絞動物、軟體動物及脊椎動物)和原生動物(單細胞動物),此外他還將海綿劃為第六個動物門類[157][156]。後來,原生動物被移到以前的原生生物界,只留下後生動物作為動物界的代名詞[158]。

對人類的作用和影響[編輯]

人類以許多其他動物物種作為食物,包括畜牧業中經過馴養的家畜,以及捕獵的野生動物(主要是通過在海中捕撈各種海魚)[159][160]。商業捕撈海魚的物種數量繁多,而相較之下商業養殖動物的物種數量較少[159][161][162]。此外,人類還會獵殺或養殖頭足類、甲殼類、雙殼類及腹足類等無脊椎動物作為食物[163]。世界各地都在飼養雞、牛、羊及豬等動物作為食物[160][164][165]。動物纖維(如羊毛)可用於製造紡織品,動物筋腱能用於綁紮,皮被廣泛用於製作鞋子等物品。人們獵捕或養殖動物獲取它們的毛皮,用來製作大衣和帽子之類的物品[166][167],甚至昆蟲也可用來製作染料(例如胭脂紅[168][169][170][171]和蟲膠[172][173])。

黑腹果蠅等動物作為模式生物在科學實驗中發揮了重要作用[174][175][176][177]。自18世紀發現疫苗開始,人們就將動物用於製造疫苗[178]。某些藥物(例如以海鞘提取物製成的抗癌藥物曲貝替定)就是基於源自動物的毒素等生物分子製成的[179]。

人們用獵犬追趕和尋回獵物[180],用猛禽來捕獲鳥類和哺乳動物[181],用拴住喉嚨的鸕鶿進行捕魚[182]。箭毒蛙用來給吹管飛鏢的尖端上毒[183][184]。從農業發展的初期開始,牛和馬等動物就一直被用於勞作和運輸[185]。各種各樣的動物被當作寵物飼養,從無脊椎動物(特別是昆蟲和狼蛛[186])到爬行動物[187]再到鳥類[188]。但是,最常見的寵物,如狗、貓及兔子等等,屬於哺乳動物[189][190][191]。人們還喜歡進行動物相關的體育運動(如馬術)[192]。不過,在動物作為與人類相關的角色與動物權利的個體自由而存在着矛盾[193]。

從古至今,動物都是藝術的題材,在史前時代的許多壁畫中即有不少動物圖繪[194],其中年代最早者至少可回溯至4萬3900年前的舊石器時代晚期[195]。著名的動物畫作包括阿爾布雷希特·丟勒在1515年畫的《丟勒的犀牛》和喬治·斯塔布斯約1762年畫的《棗紅馬》[196]。動物還經常在文學作品和電影中扮演重要角色[197],在神話和宗教中也有出現(如《梁山伯與祝英台》)[198][199]。在日本和歐洲,蝴蝶被視為人類靈魂的化身[198][200][201]。聖甲蟲在古埃及是一種神聖的動物[202]。在哺乳動物中,牛[203]、鹿[199]、馬[204]、獅子[205]、蝙蝠[206]、熊[207]和狼[208]都曾在神話中出現,是人類崇拜的對象。西方的黃道帶和中國的十二生肖也是基於動物而創造的傳說[209][210]。世界上有多個國家和地區選擇象徵國家和民族精神的動物,即為國獸。

註解[編輯]

另見[編輯]

參考資料[編輯]

- 如無特殊說明以下參考資料均為英語來源

- ^ Cresswell, Julia. The Oxford Dictionary of Word Origins 2nd. New York: Oxford University Press. 2010. ISBN 978-0-19-954793-7.

'having the breath of life', from anima 'air, breath, life'.

- ^ Animal. The American Heritage Dictionary 4th. Houghton Mifflin Company. 2006.

- ^ animal. English Oxford Living Dictionaries. [2018-07-26]. (原始內容存檔於2018-07-26).

- ^ Boly, Melanie; Seth, Anil K.; Wilke, Melanie; Ingmundson, Paul; Baars, Bernard; Laureys, Steven; Edelman, David; Tsuchiya, Naotsugu. Consciousness in humans and non-human animals: recent advances and future directions. Frontiers in Psychology. 2013, 4: 625. PMC 3814086

. PMID 24198791. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00625.

. PMID 24198791. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00625.

- ^ The use of non-human animals in research. Royal Society. [2018-06-07]. (原始內容存檔於2018-06-12).

- ^ Nonhuman definition and meaning |. Collins English Dictionary. [2018-06-07]. (原始內容存檔於2018-06-12).

- ^ Avila, Vernon L. Biology: Investigating Life on Earth. Jones & Bartlett Learning. 1995: 767–. ISBN 978-0-86720-942-6.

- ^ 8.0 8.1 Palaeos:Metazoa. Palaeos. [2018-02-25]. (原始內容存檔於2018-02-28).

- ^ Bergman, Jennifer. Heterotrophs. [2007-09-30]. (原始內容存檔於2007-08-29).

- ^ Douglas, Angela E.; Raven, John A. Genomes at the interface between bacteria and organelles. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 2003-01, 358 (1429): 5–17. PMC 1693093

. PMID 12594915. doi:10.1098/rstb.2002.1188.

. PMID 12594915. doi:10.1098/rstb.2002.1188.

- ^ Mentel, Marek; Martin, William. Anaerobic animals from an ancient, anoxic ecological niche. BMC Biology. 2010, 8: 32. PMC 2859860

. PMID 20370917. doi:10.1186/1741-7007-8-32.

. PMID 20370917. doi:10.1186/1741-7007-8-32.

- ^ Davidson, Michael W. Animal Cell Structure. [2007-09-20]. (原始內容存檔於2007-09-20).

- ^ Saupe, S.G. Concepts of Biology. [2007-09-30]. (原始內容存檔於2007-11-21).

- ^ Minkoff, Eli C. Barron's EZ-101 Study Keys Series: Biology 2nd, revised. Barron's Educational Series. 2008: 48. ISBN 978-0-7641-3920-8.

- ^ Winograd, Claudia. Germ layer | biology. Encyclopedia Britannica. 大英百科全書. [2020-05-25]. (原始內容存檔於2021-12-21).

- ^ Alberts, Bruce; Johnson, Alexander; Lewis, Julian; Raff, Martin; Roberts, Keith; Walter, Peter. Molecular Biology of the Cell 4th. Garland Science. 2002 [2017-08-29]. ISBN 978-0-8153-3218-3. (原始內容存檔於2016-12-23).

- ^ Sangwal, Keshra. Additives and crystallization processes: from fundamentals to applications. John Wiley and Sons. 2007: 212. ISBN 978-0-470-06153-4.

- ^ Becker, Wayne M. The world of the cell. Benjamin/Cummings. 1991. ISBN 978-0-8053-0870-9.

- ^ Magloire, Kim. Cracking the AP Biology Exam, 2004–2005 Edition. The Princeton Review. 2004: 45. ISBN 978-0-375-76393-9.

- ^ Starr, Cecie. Biology: Concepts and Applications without Physiology. Cengage Learning. 2007-09-25: 362, 365. ISBN 978-0-495-38150-1.

- ^ Hillmer, Gero; Lehmann, Ulrich. Fossil Invertebrates. Translated by J. Lettau. CUP Archive. 1983: 54 [2016-01-08]. ISBN 978-0-521-27028-1. (原始內容存檔於2016-05-07).

- ^ Knobil, Ernst. Encyclopedia of reproduction, Volume 1. Academic Press. 1998: 315. ISBN 978-0-12-227020-8.

- ^ Schwartz, Jill. Master the GED 2011. Peterson's. 2010: 371. ISBN 978-0-7689-2885-3.

- ^ Hamilton, Matthew B. Population genetics. Wiley-Blackwell. 2009: 55. ISBN 978-1-4051-3277-0.

- ^ Ville, Claude Alvin; Walker, Warren Franklin; Barnes, Robert D. General zoology. Saunders College Pub. 1984: 467. ISBN 978-0-03-062451-3.

- ^ Hamilton, William James; Boyd, James Dixon; Mossman, Harland Winfield. Human embryology: (prenatal development of form and function). Williams & Wilkins. 1945: 330.

- ^ Philips, Joy B. Development of vertebrate anatomy. Mosby. 1975: 176. ISBN 978-0-8016-3927-2.

- ^ The Encyclopedia Americana: a library of universal knowledge, Volume 10. Encyclopedia Americana Corp. 1918: 281.

- ^ Romoser, William S.; Stoffolano, J.G. The science of entomology. WCB McGraw-Hill. 1998: 156. ISBN 978-0-697-22848-2.

- ^ Charlesworth, D.; Willis, J.H. The genetics of inbreeding depression. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2009, 10 (11): 783–796. PMID 19834483. doi:10.1038/nrg2664.

- ^ Bernstein, H.; Hopf, F.A.; Michod, R.E. The molecular basis of the evolution of sex. Adv. Genet. Advances in Genetics. 1987, 24: 323–370. ISBN 978-0-12-017624-3. PMID 3324702. doi:10.1016/s0065-2660(08)60012-7.

- ^ Pusey, Anne; Wolf, Marisa. Inbreeding avoidance in animals. Trends Ecol. Evol. 1996, 11 (5): 201–206. PMID 21237809. doi:10.1016/0169-5347(96)10028-8.

- ^ Petrie, M.; Kempenaers, B. Extra-pair paternity in birds: Explaining variation between species and populations. Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 1998, 13 (2): 52–57. PMID 21238200. doi:10.1016/s0169-5347(97)01232-9.

- ^ FRANKHAM, RICHARD; BALLOU, JONATHAN D.; ELDRIDGE, MARK D. B.; LACY, ROBERT C.; RALLS, KATHERINE; DUDASH, MICHELE R.; FENSTER, CHARLES B. Predicting the Probability of Outbreeding Depression. Conservation Biology. 2011-04-12, 25 (3): 465–475. ISSN 0888-8892. PMID 21486369. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2011.01662.x.

- ^ Adiyodi, K.G.; Hughes, Roger N.; Adiyodi, Rita G. Reproductive Biology of Invertebrates, Volume 11, Progress in Asexual Reproduction. Wiley. 2002-07: 116. ISBN 978-0-471-48968-9.

- ^ Schatz, Phil. Concepts of Biology | How Animals Reproduce. OpenStax College. [2018-03-05]. (原始內容存檔於2018-03-06).

- ^ Marchetti, Mauro; Rivas, Victoria. Geomorphology and environmental impact assessment. Taylor & Francis. 2001: 84. ISBN 978-90-5809-344-8.

- ^ Levy, Charles K. Elements of Biology. Appleton-Century-Crofts. 1973: 108. ISBN 978-0-390-55627-1.

- ^ Begon, M.; Townsend, C.; Harper, J. Ecology: Individuals, populations and communities Third. Blackwell Science. 1996. ISBN 978-0-86542-845-4.

- ^ Allen, Larry Glen; Pondella, Daniel J.; Horn, Michael H. Ecology of marine fishes: California and adjacent waters. University of California Press. 2006: 428. ISBN 978-0-520-24653-9.

- ^ Caro, Tim. Antipredator Defenses in Birds and Mammals. University of Chicago Press. 2005: 1–6 and passim.

- ^ Simpson, Alastair G.B; Roger, Andrew J. The real 'kingdoms' of eukaryotes. Current Biology. 2004, 14 (17): R693–696. PMID 15341755. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2004.08.038.

- ^ Stevens, Alison N.P. Predation, Herbivory, and Parasitism. Nature Education Knowledge. 2010, 3 (10): 36 [2018-02-12]. (原始內容存檔於2017-09-30).

- ^ Jervis, M.A.; Kidd, N.A.C. Host-Feeding Strategies in Hymenopteran Parasitoids. Biological Reviews. 1986-11, 61 (4): 395–434. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185x.1986.tb00660.x.

- ^ Meylan, Anne. Spongivory in Hawksbill Turtles: A Diet of Glass. Science. 1988-01-22, 239 (4838): 393–395. Bibcode:1988Sci...239..393M. JSTOR 1700236. PMID 17836872. doi:10.1126/science.239.4838.393.

- ^ Schmidt-Rohr, Klaus. Oxygen Is the High-Energy Molecule Powering Complex Multicellular Life: Fundamental Corrections to Traditional Bioenergetics. 美國化學會Omega. 2020-01-28, 5 (5): 2221–2233. doi:10.1021/acsomega.9b03352.

- ^ Clutterbuck, Peter. Understanding Science: Upper Primary. Blake Education. 2000: 9. ISBN 978-1-86509-170-9.

- ^ Gupta, P.K. Genetics Classical To Modern. Rastogi Publications. 1900: 26. ISBN 978-81-7133-896-2.

- ^ Garrett, Reginald; Grisham, Charles M. Biochemistry. Cengage Learning. 2010: 535. ISBN 978-0-495-10935-8.

- ^ Castro, Peter; Huber, Michael E. Marine Biology 7th. McGraw-Hill. 2007: 376. ISBN 978-0-07-722124-9.

- ^ Rota-Stabelli, Omar; Daley, Allison C.; Pisani, Davide. Molecular Timetrees Reveal a Cambrian Colonization of Land and a New Scenario for Ecdysozoan Evolution. Current Biology. 2013, 23 (5): 392–8. PMID 23375891. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2013.01.026.

- ^ Daeschler, Edward B.; Shubin, Neil H.; Jenkins, Farish A., Jr. A Devonian tetrapod-like fish and the evolution of the tetrapod body plan. Nature. 2006-04-06, 440 (7085): 757–763. Bibcode:2006Natur.440..757D. PMID 16598249. doi:10.1038/nature04639.

- ^ Clack, Jennifer A. Getting a Leg Up on Land. Scientific American. 2005-11-21, 293 (6): 100–7. Bibcode:2005SciAm.293f.100C. PMID 16323697. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1205-100.

- ^ Margulis, Lynn; Schwartz, Karlene V.; Dolan, Michael. Diversity of Life: The Illustrated Guide to the Five Kingdoms. Jones & Bartlett Learning. 1999: 115–116. ISBN 978-0-7637-0862-7.

- ^ Clarke, Andrew. The thermal limits to life on Earth (PDF). International Journal of Astrobiology. 2014, 13 (2): 141–154 [2018-11-15]. Bibcode:2014IJAsB..13..141C. doi:10.1017/S1473550413000438. (原始內容存檔 (PDF)於2019-04-24).

- ^ Land animals. British Antarctic Survey. [2018-03-07]. (原始內容存檔於2018-11-06).

- ^ 57.0 57.1 57.2 Wood, Gerald. The Guinness Book of Animal Facts and Feats. Enfield, Middlesex : Guinness Superlatives. 1983. ISBN 978-0-85112-235-9.

- ^ Davies, Ella. The longest animal alive may be one you never thought of. BBC Earth. 2016-04-20 [2018-03-01]. (原始內容存檔於2018-03-19).

- ^ Largest mammal. Guinness World Records. [2018-03-01]. (原始內容存檔於2018-01-31).

- ^ Mazzetta, Gerardo V.; Christiansen, Per; Fariña, Richard A. Giants and Bizarres: Body Size of Some Southern South American Cretaceous Dinosaurs. Historical Biology. 2004, 16 (2–4): 71–83. doi:10.1080/08912960410001715132.

- ^ Fiala, Ivan. Myxozoa. Tree of Life Web Project. 2008-07-10 [2018-03-04]. (原始內容存檔於2018-03-01).

- ^ Kaur, H.; Singh, R. Two new species of Myxobolus (Myxozoa: Myxosporea: Bivalvulida) infecting an Indian major carp and a cat fish in wetlands of Punjab, India. Journal of Parasitic Diseases. 2011, 35 (2): 169–176. PMC 3235390

. PMID 23024499. doi:10.1007/s12639-011-0061-4.

. PMID 23024499. doi:10.1007/s12639-011-0061-4.

- ^ 63.00 63.01 63.02 63.03 63.04 63.05 63.06 63.07 63.08 63.09 63.10 63.11 63.12 63.13 Zhang, Zhi-Qiang. Animal biodiversity: An update of classification and diversity in 2013. In: Zhang, Z.-Q. (Ed.) Animal Biodiversity: An Outline of Higher-level Classification and Survey of Taxonomic Richness (Addenda 2013). Zootaxa. 2013-08-30, 3703 (1): 5 [2018-03-02]. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.3703.1.3. (原始內容存檔於2019-04-24).

- ^ 64.00 64.01 64.02 64.03 64.04 64.05 64.06 64.07 64.08 64.09 Balian, E.V.; Lévêque, C.; Segers, H.; Martens, K. Freshwater Animal Diversity Assessment. Springer. 2008: 628. ISBN 978-1-4020-8259-7.

- ^ 65.00 65.01 65.02 65.03 65.04 65.05 65.06 65.07 65.08 65.09 65.10 65.11 65.12 65.13 Hogenboom, Melissa. There are only 35 kinds of animal and most are really weird. BBC earth. [2018-03-02]. (原始內容存檔於2018-08-10).

- ^ 66.0 66.1 66.2 66.3 66.4 66.5 66.6 66.7 Poulin, Robert. Evolutionary Ecology of Parasites. Princeton University Press. 2007: 6. ISBN 978-0-691-12085-0.

- ^ 67.0 67.1 67.2 67.3 Felder, Darryl L.; Camp, David K. Gulf of Mexico Origin, Waters, and Biota: Biodiversity. Texas A&M University Press. 2009: 1111. ISBN 978-1-60344-269-5.

- ^ How many species on Earth? About 8.7 million, new estimate says. 2011-08-24 [2018-03-02]. (原始內容存檔於2018-07-01).

- ^ Mora, Camilo; Tittensor, Derek P.; Adl, Sina; Simpson, Alastair G.B.; Worm, Boris. Mace, Georgina M. , 編. How Many Species Are There on Earth and in the Ocean?. PLOS Biology. 2011-08-23, 9 (8): e1001127. PMC 3160336

. PMID 21886479. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001127.

. PMID 21886479. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001127.

- ^ Erwin, Terry L. Biodiversity at its utmost: Tropical Forest Beetles (PDF). 1997: 27–40 [2017-12-16]. (原始內容存檔 (PDF)於2018-11-09). In: Reaka-Kudla, M.L.; Wilson, D.E.; Wilson, E.O. (編). Biodiversity II

. Joseph Henry Press, Washington, D.C.

. Joseph Henry Press, Washington, D.C.

- ^ Erwin, Terry L. Tropical forests: their richness in Coleoptera and other arthropod species (PDF). The Coleopterists Bulletin. 1982, 36: 74–75 [2018-09-16]. (原始內容存檔 (PDF)於2015-09-23).

- ^ Hebert, Paul D.N.; Ratnasingham, Sujeevan; Zakharov, Evgeny V.; Telfer, Angela C.; Levesque-Beaudin, Valerie; Milton, Megan A.; Pedersen, Stephanie; Jannetta, Paul; deWaard, Jeremy R. Counting animal species with DNA barcodes: Canadian insects. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2016-08-01, 371 (1702): 20150333. PMC 4971185

. PMID 27481785. doi:10.1098/rstb.2015.0333.

. PMID 27481785. doi:10.1098/rstb.2015.0333.

- ^ Stork, Nigel E. How Many Species of Insects and Other Terrestrial Arthropods Are There on Earth?. Annual Review of Entomology. 2018-01, 63 (1): 31–45. PMID 28938083. doi:10.1146/annurev-ento-020117-043348. Stork notes that 1m insects have been named, making much larger predicted estimates.

- ^ Poore, Hugh F. Introduction. Crustacea: Malacostraca. Zoological catalogue of Australia 19.2A. CSIRO Publishing. 2002: 1–7. ISBN 978-0-643-06901-5.

- ^ 75.0 75.1 The World Conservation Union. 2014. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, 2014.3. Summary Statistics for Globally Threatened Species. Table 1: Numbers of threatened species by major groups of organisms (1996–2014) (頁面存檔備份,存於網際網路檔案館).

- ^ 76.0 76.1 76.2 76.3 Reaka-Kudla, Marjorie L.; Wilson, Don E.; Wilson, Edward O. Biodiversity II: Understanding and Protecting Our Biological Resources. Joseph Henry Press. 1996: 90. ISBN 978-0-309-52075-1.

- ^ Burton, Derek; Burton, Margaret. Essential Fish Biology: Diversity, Structure and Function. Oxford University Press. 2017: 281–282. ISBN 978-0-19-878555-2.

Trichomycteridae ... includes obligate parasitic fish. Thus 17 genera from 2 subfamilies, Vandelliinae; 4 genera, 9spp. and Stegophilinae; 13 genera, 31 spp. are parasites on gills (Vandelliinae) or skin (stegophilines) of fish.

- ^ 78.0 78.1 78.2 78.3 Nicol, David. The Number of Living Species of Molluscs. Systematic Zoology. 1969-06, 18 (2): 251–254. JSTOR 2412618. doi:10.2307/2412618.

- ^ Sluys, R. Global diversity of land planarians (Platyhelminthes, Tricladida, Terricola): a new indicator-taxon in biodiversity and conservation studies. Biodiversity and Conservation. 1999, 8 (12): 1663–1681. doi:10.1023/A:1008994925673.

- ^ 80.0 80.1 Pandian, T. J. Reproduction and Development in Platyhelminthes. CRC Press. 2020: 13–14 [2020-05-19]. ISBN 9781000054903. (原始內容存檔於2021-11-14).

- ^ Fontaneto, Diego. Marine Rotifers | An Unexplored World of Richness (PDF). JMBA Global Marine Environment: 4–5. [2018-03-02]. (原始內容存檔 (PDF)於2018-03-02).

- ^ Morand, Serge; Krasnov, Boris R.; Littlewood, D. Timothy J. Parasite Diversity and Diversification. Cambridge University Press. 2015: 44 [2018-03-02]. ISBN 978-1-107-03765-6. (原始內容存檔於2018-12-12).

- ^ 83.0 83.1 Bobrovskiy, Ilya; Hope, Janet M.; Ivantsov, Andrey; Nettersheim, Benjamin J.; Hallmann, Christian; Brocks, Jochen J. Ancient steroids establish the Ediacaran fossil Dickinsonia as one of the earliest animals. Science. 2018-09-20, 361 (6408): 1246–1249. Bibcode:2018Sci...361.1246B. PMID 30237355. doi:10.1126/science.aat7228.

- ^ Maloof, Adam C.; Rose, Catherine V.; Beach, Robert; Samuels, Bradley M.; Calmet, Claire C.; Erwin, Douglas H.; Poirier, Gerald R.; Yao, Nan; Simons, Frederik J. Possible animal-body fossils in pre-Marinoan limestones from South Australia. Nature Geoscience. 2010-08-17, 3 (9): 653–659. Bibcode:2010NatGe...3..653M. doi:10.1038/ngeo934.

- ^ Shen, Bing; Dong, Lin; Xiao, Shuhai; Kowalewski, Michał. The Avalon Explosion: Evolution of Ediacara Morphospace. Science. 2008, 319 (5859): 81–84. Bibcode:2008Sci...319...81S. PMID 18174439. doi:10.1126/science.1150279.

- ^ Chen, Zhe; Chen, Xiang; Zhou, Chuanming; Yuan, Xunlai; Xiao, Shuhai. Late Ediacaran trackways produced by bilaterian animals with paired appendages. Science Advances. 2018-06-01, 4 (6): eaao6691. Bibcode:2018SciA....4.6691C. PMC 5990303

. PMID 29881773. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aao6691.

. PMID 29881773. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aao6691.

- ^ Schopf, J. William. Evolution!: facts and fallacies. Academic Press. 1999: 7. ISBN 978-0-12-628860-5.

- ^ Zimorski, Verena; Mentel, Marek; Tielens, Aloysius G.M.; Martin, William F. Energy metabolism in anaerobic eukaryotes and Earth's late oxygenation. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2019, 140: 279–294. PMC 6856725

. PMID 30935869. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2019.03.030.

. PMID 30935869. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2019.03.030.

- ^ Erwin, D. H.; Laflamme, M.; Tweedt, S. M.; Sperling, E. A.; Pisani, D.; Peterson, K. J. The Cambrian conundrum: early divergence and later ecological success in the early history of animals. Science. 2011, 334: 1091–1097. Bibcode:2011Sci...334.1091E. PMID 22116879. doi:10.1126/science.1206375.

- ^ Maloof, A.C.; Porter, S.M.; Moore, J.L.; Dudas, F.O.; Bowring, S.A.; Higgins, J.A.; Fike, D.A.; Eddy, M.P. The earliest Cambrian record of animals and ocean geochemical change. Geological Society of America Bulletin. 2010, 122 (11–12): 1731–1774. Bibcode:2010GSAB..122.1731M. doi:10.1130/B30346.1.

- ^ New Timeline for Appearances of Skeletal Animals in Fossil Record Developed by UCSB Researchers. The Regents of the University of California. 2010-11-10 [2014-09-01]. (原始內容存檔於2014-09-03).

- ^ Conway-Morris, S. The Cambrian "explosion" of metazoans and molecular biology: would Darwin be satisfied?. The International Journal of Developmental Biology. 2003, 47 (7–8): 505–515 [2018-02-28]. PMID 14756326. (原始內容存檔於2018-07-16).

- ^ The Tree of Life. The Burgess Shale. 皇家安大略博物館. 2011-06-10 [2018-02-28]. (原始內容存檔於2018-02-16).

- ^ Campbell, Neil A.; Reece, Jane B. Biology 7th. Pearson, Benjamin Cummings. 2005: 526. ISBN 978-0-8053-7171-0.

- ^ Seilacher, Adolf; Bose, Pradip K.; Pfluger, Friedrich. Triploblastic animals more than 1 billion years ago: trace fossil evidence from india. Science. 1998-10-02, 282 (5386): 80–83. Bibcode:1998Sci...282...80S. PMID 9756480. doi:10.1126/science.282.5386.80.

- ^ Matz, Mikhail V.; Frank, Tamara M.; Marshall, N. Justin; Widder, Edith A.; Johnsen, Sönke. Giant Deep-Sea Protist Produces Bilaterian-like Traces (PDF). Current Biology. 2008-12-09, 18 (23): 1849–54 [2008-12-05]. PMID 19026540. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2008.10.028. (原始內容 (PDF)存檔於2008-12-16).

- ^ Reilly, Michael. Single-celled giant upends early evolution. NBC News. 2008-11-20 [2008-12-05]. (原始內容存檔於2013-03-29).

- ^ Bengtson, S. The fossil record of predation. Kowalewski, M.; Kelley, P.H. (編). The Paleontological Society Papers 8. The Paleontological Society: 289–317. 2002. (原始內容存檔 (PDF)於2019-10-30) 使用

|archiveurl=需要含有|url=(幫助).|chapter=被忽略 (幫助); - ^ Budd, Graham E; Jensen, Sören. The origin of the animals and a 'Savannah' hypothesis for early bilaterian evolution. Biological Reviews. 2017, 92 (1): 446–473. PMID 26588818. doi:10.1111/brv.12239.

- ^ Giribet, Gonzalo. Genomics and the animal tree of life: conflicts and future prospects. Zoologica Scripta. 2016-09-27, 45: 14–21. doi:10.1111/zsc.12215.

- ^ Evolution and Development (PDF). Carnegie Institution for Science Department of Embryology: 38. 2012-05-01 [2018-03-04]. (原始內容 (PDF)存檔於2014-03-02).

- ^ Dellaporta, Stephen; Holland, Peter; Schierwater, Bernd; Jakob, Wolfgang; Sagasser, Sven; Kuhn, Kerstin. The Trox-2 Hox/ParaHox gene of Trichoplax (Placozoa) marks an epithelial boundary. Development Genes and Evolution. 2004-04, 214 (4): 170–175. PMID 14997392. doi:10.1007/s00427-004-0390-8.

- ^ Peterson, Kevin J.; Eernisse, Douglas J. Animal phylogeny and the ancestry of bilaterians: Inferences from morphology and 18S rDNA gene sequences. Evolution and Development. 2001, 3 (3): 170–205. PMID 11440251. doi:10.1046/j.1525-142x.2001.003003170.x.

- ^ Kraemer-Eis, Andrea; Ferretti, Luca; Schiffer, Philipp; Heger, Peter; Wiehe, Thomas. A catalogue of Bilaterian-specific genes – their function and expression profiles in early development (PDF). bioRxiv. 2016 [2020-05-01]. doi:10.1101/041806. (原始內容存檔 (PDF)於2018-02-26).

- ^ Zimmer, Carl. The Very First Animal Appeared Amid an Explosion of DNA. The New York Times. 2018-05-04 [2018-05-04]. (原始內容存檔於2018-05-04).

- ^ Paps, Jordi; Holland, Peter W.H. Reconstruction of the ancestral metazoan genome reveals an increase in genomic novelty. 自然-通訊. 2018-04-30, 9 (1730 (2018)): 1730. Bibcode:2018NatCo...9.1730P. PMC 5928047

. PMID 29712911. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-04136-5.

. PMID 29712911. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-04136-5.

- ^ Peterson, Kevin J.; Cotton, James A.; Gehling, James G.; Pisani, Davide. The Ediacaran emergence of bilaterians: congruence between the genetic and the geological fossil records. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences. 2008-04-27, 363 (1496): 1435–1443. PMC 2614224

. PMID 18192191. doi:10.1098/rstb.2007.2233.

. PMID 18192191. doi:10.1098/rstb.2007.2233.

- ^ Parfrey, Laura Wegener; Lahr, Daniel J.G.; Knoll, Andrew H.; Katz, Laura A. Estimating the timing of early eukaryotic diversification with multigene molecular clocks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2011-08-16, 108 (33): 13624–13629. Bibcode:2011PNAS..10813624P. PMC 3158185

. PMID 21810989. doi:10.1073/pnas.1110633108.

. PMID 21810989. doi:10.1073/pnas.1110633108.

- ^ Raising the Standard in Fossil Calibration. Fossil Calibration Database. [2018-03-03]. (原始內容存檔於2018-03-07).

- ^ Laumer, Christopher E.; Gruber-Vodicka, Harald; Hadfield, Michael G.; Pearse, Vicki B.; Riesgo, Ana; Marioni, John C.; Giribet, Gonzalo. Support for a clade of Placozoa and Cnidaria in genes with minimal compositional bias. eLife. 2018, 2018;7: e36278. PMC 6277202

. PMID 30373720. doi:10.7554/eLife.36278.

. PMID 30373720. doi:10.7554/eLife.36278.

- ^ Adl, Sina M.; Bass, David; Lane, Christopher E.; Lukeš, Julius; Schoch, Conrad L.; Smirnov, Alexey; Agatha, Sabine; Berney, Cedric; Brown, Matthew W. Revisions to the Classification, Nomenclature, and Diversity of Eukaryotes. Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology. 2018, 66 (1): 4–119. PMC 6492006

. PMID 30257078. doi:10.1111/jeu.12691.

. PMID 30257078. doi:10.1111/jeu.12691.

- ^ 112.0 112.1 Barnes, Robert D. Invertebrate Zoology. Holt-Saunders International. 1982: 84–85. ISBN 978-0-03-056747-6.

- ^ 113.0 113.1 Introduction to Placozoa. UCMP Berkeley. [2018-03-10]. (原始內容存檔於2018-03-25).

- ^ Sumich, James L. Laboratory and Field Investigations in Marine Life. Jones & Bartlett Learning. 2008: 67. ISBN 978-0-7637-5730-4.

- ^ Jessop, Nancy Meyer. Biosphere; a study of life. Prentice-Hall. 1970: 428.

- ^ Sharma, N.S. Continuity And Evolution Of Animals. Mittal Publications. 2005: 106. ISBN 978-81-8293-018-6.

- ^ 117.0 117.1 117.2 Martindale, Mark Q; Finnerty, John R; Henry, Jonathan Q. The Radiata and the evolutionary origins of the bilaterian body plan. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 2002-09-01, 24 (3): 358–365. ISSN 1055-7903. doi:10.1016/S1055-7903(02)00208-7 (英語).

- ^ Safra, Jacob E. The New Encyclopædia Britannica, Volume 16. Encyclopædia Britannica. 2003: 523. ISBN 978-0-85229-961-6.

- ^ Kotpal, R.L. Modern Text Book of Zoology: Invertebrates. Rastogi Publications. 2012: 184. ISBN 978-81-7133-903-7.

- ^ Bhamrah, H.S.; Juneja, Kavita. An Introduction to Porifera. Anmol Publications. 2003: 58. ISBN 978-81-261-0675-2.

- ^ 121.0 121.1 121.2 Laumer, Christopher E.; Fernández, Rosa; Lemer, Sarah; Combosch, David; Kocot, Kevin M.; Riesgo, Ana; Andrade, Sónia C. S.; Sterrer, Wolfgang; Sørensen, Martin V. Revisiting metazoan phylogeny with genomic sampling of all phyla. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2019-07-10, 286 (1906): 20190831 [2020-06-18]. PMC 6650721

. PMID 31288696. doi:10.1098/rspb.2019.0831. (原始內容存檔於2021-09-16).

. PMID 31288696. doi:10.1098/rspb.2019.0831. (原始內容存檔於2021-09-16).

- ^ Whelan, Nathan V.; Kocot, Kevin M.; Moroz, Tatiana P.; Mukherjee, Krishanu; Williams, Peter; Paulay, Gustav; Moroz, Leonid L.; Halanych, Kenneth M. Ctenophore relationships and their placement as the sister group to all other animals. Nature Ecology & Evolution. 2017-11, 1 (11): 1737–1746 [2020-06-18]. ISSN 2397-334X. doi:10.1038/s41559-017-0331-3. (原始內容存檔於2021-11-26) (英語).

- ^ 123.0 123.1 Minelli, Alessandro. Perspectives in Animal Phylogeny and Evolution. Oxford University Press. 2009: 53. ISBN 978-0-19-856620-5.

- ^ 124.0 124.1 124.2 Brusca, Richard C. Introduction to the Bilateria and the Phylum Xenacoelomorpha | Triploblasty and Bilateral Symmetry Provide New Avenues for Animal Radiation (PDF). Invertebrates (Sinauer Associates). 2016: 345–372 [2018-03-04]. ISBN 978-1-60535-375-3. (原始內容存檔 (PDF)於2019-04-24).

- ^ Quillin, K.J. Ontogenetic scaling of hydrostatic skeletons: geometric, static stress and dynamic stress scaling of the earthworm lumbricus terrestris. The Journal of Experimental Biology. 1998-05, 201 (12): 1871–1883 [2020-05-01]. PMID 9600869. (原始內容存檔於2020-06-17).

- ^ Telford, Maximilian J. Resolving Animal Phylogeny: A Sledgehammer for a Tough Nut?. Developmental Cell. 2008, 14 (4): 457–459. PMID 18410719. doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2008.03.016.

- ^ Philippe, H.; Brinkmann, H.; Copley, R.R.; Moroz, L.L.; Nakano, H.; Poustka, A.J.; Wallberg, A.; Peterson, K.J.; Telford, M.J. Acoelomorph flatworms are deuterostomes related to Xenoturbella. Nature. 2011, 470 (7333): 255–258. Bibcode:2011Natur.470..255P. PMC 4025995

. PMID 21307940. doi:10.1038/nature09676.

. PMID 21307940. doi:10.1038/nature09676.

- ^ Perseke, M.; Hankeln, T.; Weich, B.; Fritzsch, G.; Stadler, P.F.; Israelsson, O.; Bernhard, D.; Schlegel, M. The mitochondrial DNA of Xenoturbella bocki: genomic architecture and phylogenetic analysis (PDF). Theory Biosci. 2007-08, 126 (1): 35–42 [2018-03-04]. PMID 18087755. doi:10.1007/s12064-007-0007-7. (原始內容 (PDF)存檔於2019-04-24).

- ^ Cannon, Johanna T.; Vellutini, Bruno C.; Smith III, Julian.; Ronquist, Frederik; Jondelius, Ulf; Hejnol, Andreas. Xenacoelomorpha is the sister group to Nephrozoa. Nature. 2016-02-03, 530 (7588): 89–93. Bibcode:2016Natur.530...89C. PMID 26842059. doi:10.1038/nature16520.

- ^ Valentine, James W. Cleavage patterns and the topology of the metazoan tree of life. PNAS. 1997-07, 94 (15): 8001–8005. Bibcode:1997PNAS...94.8001V. PMC 21545

. PMID 9223303. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.15.8001.

. PMID 9223303. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.15.8001.

- ^ Peters, Kenneth E.; Walters, Clifford C.; Moldowan, J. Michael. The Biomarker Guide: Biomarkers and isotopes in petroleum systems and Earth history 2. Cambridge University Press. 2005: 717. ISBN 978-0-521-83762-0.

- ^ Hejnol, A.; Martindale, M.Q. Telford, M.J.; Littlewood, D.J. , 編. The mouth, the anus, and the blastopore – open questions about questionable openings. Animal Evolution – Genomes, Fossils, and Trees (Oxford University Press). 2009: 33–40 [2018-03-01]. ISBN 978-0-19-957030-0. (原始內容存檔於2018-10-28).

- ^ Safra, Jacob E. The New Encyclopædia Britannica, Volume 1; Volume 3. Encyclopædia Britannica. 2003: 767. ISBN 978-0-85229-961-6.

- ^ Hyde, Kenneth. Zoology: An Inside View of Animals. Kendall Hunt. 2004: 345. ISBN 978-0-7575-0997-1.

- ^ Alcamo, Edward. Biology Coloring Workbook. The Princeton Review. 1998: 220. ISBN 978-0-679-77884-4.

- ^ Holmes, Thom. The First Vertebrates. Infobase Publishing. 2008: 64. ISBN 978-0-8160-5958-4.

- ^ Rice, Stanley A. Encyclopedia of evolution. Infobase Publishing. 2007: 75. ISBN 978-0-8160-5515-9.

- ^ Tobin, Allan J.; Dusheck, Jennie. Asking about life. Cengage Learning. 2005: 497. ISBN 978-0-534-40653-0.

- ^ Simakov, Oleg; Kawashima, Takeshi; Marlétaz, Ferdinand; Jenkins, Jerry; Koyanagi, Ryo; Mitros, Therese; Hisata, Kanako; Bredeson, Jessen; Shoguchi, Eiichi. Hemichordate genomes and deuterostome origins. Nature. 2015-11-26, 527 (7579): 459–465. Bibcode:2015Natur.527..459S. PMC 4729200

. PMID 26580012. doi:10.1038/nature16150.

. PMID 26580012. doi:10.1038/nature16150.

- ^ Dawkins, Richard. The Ancestor's Tale: A Pilgrimage to the Dawn of Evolution. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. 2005: 381. ISBN 978-0-618-61916-0.

- ^ Prewitt, Nancy L.; Underwood, Larry S.; Surver, William. BioInquiry: making connections in biology. John Wiley. 2003: 289. ISBN 978-0-471-20228-8.

- ^ Schmid-Hempel, Paul. Parasites in social insects. Princeton University Press. 1998: 75. ISBN 978-0-691-05924-2.

- ^ Miller, Stephen A.; Harley, John P. Zoology. McGraw-Hill Higher Education. 2006: 173.

- ^ Shankland, M.; Seaver, E.C. Evolution of the bilaterian body plan: What have we learned from annelids?. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2000, 97 (9): 4434–4437. Bibcode:2000PNAS...97.4434S. JSTOR 122407. PMC 34316

. PMID 10781038. doi:10.1073/pnas.97.9.4434.

. PMID 10781038. doi:10.1073/pnas.97.9.4434.

- ^ 145.0 145.1 Struck, Torsten H.; Wey-Fabrizius, Alexandra R.; Golombek, Anja; Hering, Lars; Weigert, Anne; Bleidorn, Christoph; Klebow, Sabrina; Iakovenko, Nataliia; Hausdorf, Bernhard; Petersen, Malte; Kück, Patrick; Herlyn, Holger; Hankeln, Thomas. Platyzoan Paraphyly Based on Phylogenomic Data Supports a Noncoelomate Ancestry of Spiralia. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2014, 31 (7): 1833–1849. PMID 24748651. doi:10.1093/molbev/msu143.

- ^ Fröbius, Andreas C.; Funch, Peter. Rotiferan Hox genes give new insights into the evolution of metazoan bodyplans. Nature Communications. 2017-04, 8 (1): 9. Bibcode:2017NatCo...8....9F. PMC 5431905

. PMID 28377584. doi:10.1038/s41467-017-00020-w.

. PMID 28377584. doi:10.1038/s41467-017-00020-w.

- ^ Hervé, Philippe; Lartillot, Nicolas; Brinkmann, Henner. Multigene Analyses of Bilaterian Animals Corroborate the Monophyly of Ecdysozoa, Lophotrochozoa, and Protostomia. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2005-05, 22 (5): 1246–1253. PMID 15703236. doi:10.1093/molbev/msi111.

- ^ Introduction to the Lophotrochozoa | Of molluscs, worms, and lophophores.... UCMP Berkeley. [2018-02-28]. (原始內容存檔於2000-08-16).

- ^ Giribet, G.; Distel, D.L.; Polz, M.; Sterrer, W.; Wheeler, W.C. Triploblastic relationships with emphasis on the acoelomates and the position of Gnathostomulida, Cycliophora, Plathelminthes, and Chaetognatha: a combined approach of 18S rDNA sequences and morphology. Syst Biol. 2000, 49 (3): 539–562. PMID 12116426. doi:10.1080/10635159950127385.

- ^ Kim, Chang Bae; Moon, Seung Yeo; Gelder, Stuart R.; Kim, Won. Phylogenetic Relationships of Annelids, Molluscs, and Arthropods Evidenced from Molecules and Morphology. Journal of Molecular Evolution. 1996-09, 43 (3): 207–215. Bibcode:1996JMolE..43..207K. PMID 8703086. doi:10.1007/PL00006079.

- ^ 151.0 151.1 Gould, Stephen Jay. The Lying Stones of Marrakech. Harvard University Press. 2011: 130–134. ISBN 978-0-674-06167-5.

- ^ Leroi, Armand Marie. The Lagoon: How Aristotle Invented Science. Bloomsbury. 2014: 111–119, 270–271. ISBN 978-1-4088-3622-4.

- ^ Linnaeus, Carl. Systema naturae per regna tria naturae :secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. 第十版. Holmiae (Laurentii Salvii). 1758 [2008-09-22]. (原始內容存檔於2008-10-10) (拉丁語).

- ^ Espèce de. Reverso Dictionnnaire. [2018-03-01]. (原始內容存檔於2013-07-28).

- ^ De Wit, Hendrik C.D. Histoire du Développement de la Biologie, Volume III. Presses Polytechniques et Universitaires Romandes. 1994: 94–96. ISBN 978-2-88074-264-5.

- ^ 156.0 156.1 Valentine, James W. On the Origin of Phyla. University of Chicago Press. 2004: 7–8. ISBN 978-0-226-84548-7.

- ^ Haeckel, Ernst. Anthropogenie oder Entwickelungsgeschichte des menschen. W. Engelmann. 1874: 202 (德語).

- ^ Hutchins, Michael. Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia 2nd. Gale. 2003: 3. ISBN 978-0-7876-5777-2.

- ^ 159.0 159.1 Fisheries and Aquaculture. FAO. [2016-07-08]. (原始內容存檔於2009-05-19).

- ^ 160.0 160.1 Graphic detail Charts, maps and infographics. Counting chickens. The Economist. 2011-07-27 [2016-06-23]. (原始內容存檔於2016-07-15).

- ^ Helfman, Gene S. Fish Conservation: A Guide to Understanding and Restoring Global Aquatic Biodiversity and Fishery Resources. Island Press. 2007: 11. ISBN 978-1-59726-760-1.

- ^ World Review of Fisheries and Aquaculture (PDF). fao.org. FAO. [2015-08-13]. (原始內容存檔 (PDF)於2015-08-28).

- ^ Shellfish climbs up the popularity ladder. Seafood Business. 2002-01 [2016-07-08]. (原始內容存檔於2012-11-05).

- ^ Cattle Today. Breeds of Cattle at CATTLE TODAY. Cattle-today.com. [2013-10-15]. (原始內容存檔於2011-07-15).

- ^ Lukefahr, S.D.; Cheeke, P.R. Rabbit project development strategies in subsistence farming systems. 聯合國糧食及農業組織. [2016-06-23]. (原始內容存檔於2016-05-06).

- ^ Animals Used for Clothing. PETA. 2011-02-17 [2016-07-08]. (原始內容存檔於2016-06-29).

- ^ Ancient fabrics, high-tech geotextiles. Natural Fibres. [2016-07-08]. (原始內容存檔於2016-07-20).

- ^ Cochineal and Carmine. Major colourants and dyestuffs, mainly produced in horticultural systems. FAO. [2015-06-16]. (原始內容存檔於2018-03-06).

- ^ Guidance for Industry: Cochineal Extract and Carmine. FDA. [2016-07-06]. (原始內容存檔於2016-07-13).

- ^ Barber, E.J.W. Prehistoric Textiles. Princeton University Press. 1991: 230–231. ISBN 978-0-691-00224-8.

- ^ Munro, John H. Jenkins, David , 編. Medieval Woollens: Textiles, Technology, and Organisation. The Cambridge History of Western Textiles (Cambridge University Press). 2003: 214–215. ISBN 978-0-521-34107-3.

- ^ How Shellac Is Manufactured. The Mail (Adelaide, SA : 1912–1954). 1937-12-18 [2015-07-17].

- ^ Pearnchob, N.; Siepmann, J.; Bodmeier, R. Pharmaceutical applications of shellac: moisture-protective and taste-masking coatings and extended-release matrix tablets. Drug Development and Industrial Pharmacy. 2003, 29 (8): 925–938. PMID 14570313. doi:10.1081/ddc-120024188.

- ^ Genetics Research. Animal Health Trust. [2016-06-24]. (原始內容存檔於2017-12-12).

- ^ Drug Development. Animal Research.info. [2016-06-24]. (原始內容存檔於2016-06-08).

- ^ Animal Experimentation. BBC. [2016-07-08]. (原始內容存檔於2016-07-01).

- ^ EU statistics show decline in animal research numbers. Speaking of Research. 2013 [2016-01-24]. (原始內容存檔於2017-10-06).

- ^ Vaccines and animal cell technology. Animal Cell Technology Industrial Platform. [2016-07-09]. (原始內容存檔於2016-07-13).

- ^ Medicines by Design. National Institute of Health. [2016-07-09]. (原始內容存檔於2016-06-04).

- ^ Fergus, Charles. Gun Dog Breeds, A Guide to Spaniels, Retrievers, and Pointing Dogs. The Lyons Press. 2002. ISBN 978-1-58574-618-7.

- ^ History of Falconry. The Falconry Centre. [2016-04-22]. (原始內容存檔於2016-05-29).

- ^ King, Richard J. The Devil's Cormorant: A Natural History. University of New Hampshire Press. 2013: 9. ISBN 978-1-61168-225-0.

- ^ AmphibiaWeb – Dendrobatidae. AmphibiaWeb. [2008-10-10]. (原始內容存檔於2011-08-10).

- ^ Heying, H. Dendrobatidae. Animal Diversity Web. 2003 [2016-07-09]. (原始內容存檔於2011-02-12).

- ^ Pond, Wilson G. Encyclopedia of Animal Science. CRC Press. 2004: 248–250 [2018-02-22]. ISBN 978-0-8247-5496-9. (原始內容存檔於2017-07-03).

- ^ Other bugs. Keeping Insects. [2016-07-08]. (原始內容存檔於2016-07-07).

- ^ Kaplan, Melissa. So, you think you want a reptile?. Anapsid.org. [2016-07-08]. (原始內容存檔於2016-07-03).

- ^ Pet Birds. PDSA. [2016-07-08]. (原始內容存檔於2016-07-07).

- ^ Animals in Healthcare Facilities (PDF). 2012 [2020-05-01]. (原始內容 (PDF)存檔於2016-03-04).

- ^ The Humane Society of the United States. U.S. Pet Ownership Statistics. [2012-04-27]. (原始內容存檔於2012-04-07).

- ^ USDA. U.S. Rabbit Industry profile (PDF). [2013-07-10]. (原始內容 (PDF)存檔於2013-10-20).

- ^ Hummel, Richard. Hunting and Fishing for Sport: Commerce, Controversy, Popular Culture. Popular Press. 1994. ISBN 978-0-87972-646-1.

- ^ Plous, S. The Role of Animals in Human Society. Journal of Social Issues. 1993, 49 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.1993.tb00906.x.

- ^ Potter, P. Paleolithic Murals and the Global Wildlife Trade. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2005, 11 (7): 1164–1165. ISSN 1080-6040. doi:10.3201/eid1107.AC1107.

- ^ Aubert, M.; Lebe, R.; Oktaviana, A. A.; Tang, M.; Hamrullah, B. B.; Jusdi, A.; Abdullah; Hakim, B.; Zhao, J.-X.; Geria, I. M.; Sulistyarto, P. H.; Sardi, R.; Brumm, A. Earliest hunting scene in prehistoric art. Nature. 2019, 576 (7787): 442–445 [2020-06-09]. ISSN 0028-0836. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1806-y. (原始內容存檔於2019-12-11).

- ^ Jones, Jonathan. The top 10 animal portraits in art. The Guardian. 2014-06-27 [2016-06-24]. (原始內容存檔於2016-05-18).

- ^ Paterson, Jennifer. Animals in Film and Media. Oxford Bibliographies. 2013-10-29 [2016-06-24]. doi:10.1093/obo/9780199791286-0044. (原始內容存檔於2016-06-14).

- ^ 198.0 198.1 Hearn, Lafcadio. Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange Things. Dover. 1904. ISBN 978-0-486-21901-1.

- ^ 199.0 199.1 Deer. Trees for Life. [2016-06-23]. (原始內容存檔於2016-06-14).

- ^ Louis, Chevalier de Jaucourt (Biography). Butterfly. Encyclopedia of Diderot and d'Alembert. 2011-01 [2016-07-10]. (原始內容存檔於2016-08-11).

- ^ Hutchins, M., Arthur V. Evans, Rosser W. Garrison and Neil Schlager (Eds) (2003) Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia, 2nd edition. Volume 3, Insects. Gale, 2003.

- ^ Ben-Tor, Daphna. Scarabs, A Reflection of Ancient Egypt. Jerusalem: Israel Museum. 1989: 8. ISBN 978-965-278-083-6.

- ^ Biswas, Soutik. Why the humble cow is India's most polarising animal. BBC News (BBC). 2015-10-15 [2016-07-09]. (原始內容存檔於2016-11-22).

- ^ Robert Hans van Gulik. Hayagrīva: The Mantrayānic Aspect of Horse-cult in China and Japan. Brill Archive. : 9.

- ^ Grainger, Richard. Lion Depiction across Ancient and Modern Religions. Alert. 2012-06-24 [2016-07-06]. (原始內容存檔於2016-09-23).

- ^ Read, Kay Almere; Gonzalez, Jason J. Mesoamerican Mythology. Oxford University Press. 2000: 132–134.

- ^ Wunn, Ina. Beginning of Religion. Numen. 2000-01, 47 (4): 417–452. doi:10.1163/156852700511612.

- ^ McCone, Kim R. Meid, W. , 編. Hund, Wolf, und Krieger bei den Indogermanen. Studien zum indogermanischen Wortschatz (Innsbruck). 1987: 101–154.

- ^ Lau, Theodora. The Handbook of Chinese Horoscopes. New York: Souvenir Press. 2005: 2–8, 30–35, 60–64, 88–94, 118–124, 148–153, 178–184, 208–213, 238–244, 270–278, 306–312, 338–344.

- ^ Tester, S. Jim. A History of Western Astrology. Boydell & Brewer. 1987: 31–33 and passim. ISBN 978-0-85115-446-6.

外部連結[編輯]

| 維基詞典上的字詞解釋 | |

| 維基共享資源上的多媒體資源 | |

| 維基新聞上的新聞 | |

| 維基語錄上的名言 | |

| 維基文庫上的原始文獻 | |

| 維基教科書上的教科書和手冊 | |

| 維基學院上的學習資源 | |

| 維基物種上的相關資訊:動物 |

中文鏈接[編輯]

- 簡體中文

- 繁體中文

外文鏈接[編輯]

- Tree of Life Project(頁面存檔備份,存於網際網路檔案館),生命之樹計劃

- Animal Diversity Web(頁面存檔備份,存於網際網路檔案館),密歇根大學的動物數據庫:顯示生物分類、圖像和其他資訊

- ARKive – 瀕危或受保護物種的多媒體數據庫

- IUCN Red List of Threatened Species(頁面存檔備份,存於網際網路檔案館),國際自然保護聯盟瀕危物種紅色名錄

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||