無政府共產主義

| 系列條目 |

| 無政府共產主義 |

|---|

|

無政府共產主義[a][15][16](英語:anarcho-communism[17][18][19][20])是一種支持廢除國家、資本主義、僱傭勞動、等級制度[21]及生產資料私有制(但無政府共產主義尊重在集體所有制下的個人財產[22]),同時擁護生產資料公有制[23][24]及由工人委員會所構成的橫向網絡所統領下依照各盡所能、各取所需進行直接民主制[25][26]的政治哲學及思想流派。其中的一些流派,比如暴動無政府主義受利己主義和激進個人主義影響頗深,並認為無政府共產主義是實現個人自由的最好社會組織形式[27][28][29][30]。大多數無政府共產主義者視無政府共產主義為一種調和個人與社會之間矛盾的方式[31][32][33][34][35]。

無政府共產主義發展自法國大革命後的激進社會主義潮流[36][37],但直到第一國際在意大利的分部成立後才成型[38]。俄國思想家克魯泡特金在無政府共產主義中影響力十分巨大,並影響到了其後的內部分化[39]。迄今為止,最知名的無政府共產主義社群例包含1936年西班牙革命中的無政府工團主義地區[40]及在1918年至1921年俄國內戰中由烏克蘭革命者內斯托爾·伊萬諾維奇·馬赫諾所統領的馬赫諾運動。馬赫諾運動受克魯泡特金著作中的無政府共產主義及集體無政府主義影響極大,且一度擊退白軍和紅軍,統治烏克蘭的大多數地區,但最終被布爾什維克所佔領[41]。

1929年,韓國無政府共產主義聯合會在崇尚無政府主義和獨立行動主義的將軍金佐鎮的支持下一度建立了一個無政府共產主義社會,但最終隨着大日本帝國暗殺了金佐鎮並自南方入侵該地區,同時中國國民黨從北部入侵該地區,該地區很快便喪失了自治權,最終被併入大日本帝國的附庸滿洲國。在1936年開始的西班牙內戰中,西班牙無政府主義者經過在西班牙革命期間的努力和影響,一度在阿拉貢的多數地區建立了一個無政府主義社會,並且將無政府共產主義傳播至了雷凡特、安達盧西亞及加泰羅尼亞,但最終被佛朗哥所統領的國民軍所擊敗[42]。

歷史[編輯]

早期先驅[編輯]

一些早期基督教社區被認為具有無政府共產主義的傾向[43]。弗朗克·西弗·比林斯稱「耶穌主義」是無政府主義與共產主義的結合體[44]。晚期基督教平等主義社區的典例是英格蘭的挖掘派[45][46]。該運動的領導者傑拉德·溫斯坦利在他1649年的小冊子《新正義法典》中寫道:「不應有買賣、不應有集市或市場,但整個地球應該是每個人共有的寶藏」、「不應有統治他人的統治者,但每個人應是自己的統治者。」[47][36]

挖掘派抵制統治階級和國王的暴政,以合作的方式完成工作,管理供應並提高社會生產力。由於挖掘派建立的公社沒有私有財產,沒有經濟交換(所有物品、貨物和服務都由集體所有),他們的公社可以被稱為早期的共產主義社區,這些公社分佈在英格蘭的農村地區。

在第一次工業革命之前,整個歐洲大陸盛行土地和財產共同所有的風氣,但挖掘派因其反對君主統治的鬥爭而顯得與眾不同。他們在查理一世倒台後又因提倡工人自治而再次興起。

1703年,路易·拉洪坦在其小說《北美新航路》一書中概述了北美大陸的原住民社區是如何合作和組織的。拉洪坦發現殖民前北美的農業社會和社群無論是經濟結構角度還是從沒有任何國家角度都與歐洲基於君主制的、不平等的國家制度完全不同。他寫道,土著人處於「無政府狀態」的生活中,這也是這個詞第一次被用來表示混亂以外的東西[48]。他具體寫道,殖民前的北美沒有牧師、法院、法律、警察、國家部長,也沒有財產的區分,因此他們都是平等的,都在一起繁榮,沒有辦法區分貧富[49]。

法國大革命期間,席爾凡·馬雷夏爾在《平等者宣言》中要求「共同享有地球的產物」,並期待「貧富、大小、主僕、統治與被統治之間的噁心差別」的消失[50][36]。

約瑟夫·迪亞契與1848年革命[編輯]

約瑟夫·迪亞契是早期的無政府共產主義者,也是第一位稱自己為自由意志主義者的人。[51]他提出與普魯東不同的看法:「工人無權於他或她勞動所得的產物,但有權滿足他或她的需求,無論其性質為何」。[36][52]無政府主義史學家麥克斯·奈特勞稱自由意志共產主義在歷史上第一次被使用是在1880年11月法國的一個無政府主義大會上,該大會採用了這個詞來更清楚地描述其理論[53]。隨後法國無政府主義記者、四卷本《無政府主義百科全書》的建立者及主編塞巴斯蒂安·富爾於1895年創辦了《自由意志主義者》周報[54]。

第一國際[編輯]

| 系列條目 |

| 無政府主義 |

|---|

|

作為一套連貫的現代經濟政治哲學,無政府共產主義最早的支持者包括第一國際意大利分部的卡洛·卡菲羅、埃米利奧·科維利、埃里科·馬拉泰斯塔、安德烈·科斯塔及一些前馬志尼共和派[55]。集體無政府主義者主張在按需分配下保留勞動報酬制度[56],但主張在革命後向共產制度轉型時廢除勞動報酬制度,改用按需分配製度。受到巴枯寧的影響,詹姆士·季佑姆在論文《關於社會組織》中提到:「當……生產超越了消費……每個人將從社會豐富的物品儲備中得到所需,不用擔憂耗盡;而且道德情操將在自由與平等間高度發展,工人將會阻止,或大量減少濫用與浪費。」[57]

集體無政府主義者認為應將生產資料的所有權集體化,同時保留與每個人的勞動量和勞動種類相稱的報酬,而無政府共產主義者則進一步要求將勞動產物同樣集體化。雖然這兩個團體都反對資本主義,但無政府共產主義者不再認同蒲魯東和巴枯寧認為個人有權獲得其個人勞動的產品這一點。埃里科·馬拉泰斯塔認為:「與其冒着混淆的風險區分你和我各自所做的事情,不如讓我們都工作,把一切生產所得放在一起。這樣,每個人都能竭盡所能地勞動直到物質極大充裕,每個人都能儘可能地取其所需直到某一物質不再極大富裕」[58]。

卡菲羅在他1880年的著作《安那其與共產主義》中進一步解釋道,勞動產品的私有化將導致資本的不平等積累,從而導致社會階級及其對立的重新出現;進而導致國家的復活:「如果我們容許私人佔有勞動產品,我們就將被迫保留貨幣,使財富或多或少地按照個人的功績而非個人的需要積累」[36]。1876年,受警察活動影響,第一國際的意大利聯合會不得不在佛羅倫薩外的一個森林裏舉行了佛羅倫薩會議,他們宣佈了無政府共產主義遵循的原則如下:

第一國際意大利聯合會認為,集體化勞動產品是對集體主義方案的必要補充,一切人為滿足一切人的需要提供援助是符合團結原則的唯一生產和消費規則。意大利聯合會在佛羅倫薩舉行的第一國際會議就這一點已達成一致。

馬拉泰斯塔和卡菲羅後來將上述原則整理進了一份文章,並將其發表在了瑞士汝拉聯盟的公報上。

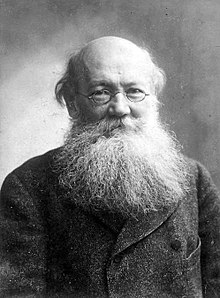

彼得·阿列克謝耶維奇·克魯泡特金[編輯]

彼得·阿列克謝耶維奇·克魯泡特金常被視為最重要的無政府共產主義理論家,他在他的著作《麵包與自由》和《田野、工廠和工場》中概述了他的無政府共產主義經濟學理念。克魯泡特金相信合作比競爭對人類益處更大,並在《互助論:進化的一個要素》一書中闡述了在大自然中能支持這一點的證據。克魯泡特金支持通過「全部社會財富收歸公有」的方式廢除私有制[59],並以此為基礎組織起平等的自願聯合組織管理經濟[60],根據個人的物質需要而非根據勞動來分配商品[61]。克魯泡特金還認為,隨着社會的進步,這些物質需要將不僅僅僅局限於純粹的物質需要:「他的物質的需要一經滿足,其他的可以說是帶有藝術性質的欲求,便會立刻發生。這樣的欲求種類很多,而且是因人而異的;社會愈文明,個性愈發達,則欲望的種類也愈多」[62]。此外,克魯泡特金堅持認為在無政府共產主義社會中「房屋、田地、工廠不應再歸私人佔有,而應該成為公共的財產」[63]。

由於無政府共產主義的目標是將「收穫或製造的產品交由所有人處置,讓每個人都有自由在自己的家中隨意地使用它們」[64],克魯泡特金支持將私有財產征為公有財產或共有財產(但仍尊重個人財產),以確保每個人都能獲得他們需要的東西,而不必出賣勞動力,他認為:

總之,克魯泡特金認為無政府共產主義下的經濟可以如此運作:

假定現在有一個居民不過數百萬的社會從事於農業及種種的工業——例如,巴黎和塞納—瓦茲省。假定這個社會裏的所有的兒童都學習用自己的腦和手勞動。除開那些從事教育兒童的婦人而外,凡是成年的人,從二十歲或二十二歲起,到四十五歲或五十歲止,每天都應該勞動五小時而且還要從事一種這城裏所認為必需的職業,但任其選擇任何部門。這樣的社會才能夠保證其中一切人的安樂。比今日中產階級所享受到的安樂還要實在些。並且這個社會裏每個工人至少每天有五小時的時間用在科學、藝術以及那些不便歸在必需品的項下的個人的欲求(在人類生產力增加的時候,這些東西也成為必需品,不再是奢侈難得的東西)上面的。

— 彼得·克魯泡特金, 《麵包與自由》[66]

組織主義、暴動主義與無政府共產主義的擴張[編輯]

1876年,意大利無政府主義者埃里科·馬拉泰斯塔在第一國際的伯爾尼會議上認為革命中包含的「行動勝過其言語」,因此行動是宣傳的最有效方式。他在汝拉聯盟的公報發表文章宣佈「第一國際意大利聯合會相信叛亂的事實——也就是說社會主義原則註定要通過行動確立這件事——是對大眾最有效的宣傳方式。」[67]

自無政府共產主義於19世紀中葉誕生以來,其支持者就一直與支持巴枯寧的集體無政府主義者之間進行着激烈的辯論,辯論的主題多種多樣,比如對無政府主義的定義、是否應參加工團主義鬥爭、是否應參加工人運動[39]。

經濟學理論[編輯]

| 共產主義 |

|---|

|

無政府共產主義的理論核心是廢除貨幣、價格和僱傭勞動。財富的分配以自決的需求為基礎,人們可以自由地從事他們認為最充實的活動,不必再從事無法體現他們氣質和才能的工作[35]。

無政府共產主義者認為,沒有任何有效的方法能衡量一個人對經濟貢獻的價值,因為所有的財富都是所有人及過去所有人共同勞作的結果[68]。例如,如果不考慮交通、食物、水、住所、休息、機器效率、情緒等等對生產的貢獻,就無法衡量一個工廠工人的日常生產價值。要真正賦予任何東西以定量的經濟價值,就需要考慮到大量的外部因素和貢獻因素——特別是當前或過去的勞動對未來勞動效率提升這一點。克魯泡特金稱:「要把這些人各個間的工作劃出一個區別來,這是完全不可能的。依照他們工作的結果來估量他們的工作,是不合理的;把他們的全工作分作若干部分,以勞動的鐘點來算分數,也是不合理的。只有一件事情是對的:就是把需要(欲求)放在工作之上,不管工作如何,只管需要如何,第一應該承認一切參加生產做工的人,都有生活的權利,其次應該承認他們的安樂的權利」[69][56]。

共產無政府主義與集體無政府主義有許多相似點,但兩者並不相同。集體無政府主義認同集體所有制,而共產無政府主義則直接否定了所有制概念本身,轉而支持使用制的概念[70]。而且,「地主」和「佃戶」之間的抽象關係也將不復存在,因為這種所有權被無政府共產主義者認為是在有條件的法律脅迫下發生的,並不是佔據建築物或空間的絕對必要條件(知識產權也將消失,因為它們也是一種私有財產的形式)。除了認為租金和其他費用是剝削性的,無政府共產主義者還認為這些是迫使人們去執行無關事務的壓力。例如,他們質疑為什麼一個人每天必須工作「X小時」才能僅僅居住在某個地方。因此,他們認為,與其為了賺取工資而有條件地工作,不如直接為眼前的目標工作[35]。

免費商店[編輯]

1960年代反文化運動團體「挖掘者」開設了許多免費商店,在這些商店中有免費的食物、藥物、紙幣發放,且有免費的音樂會在此舉辦[71][72]。挖掘者團體的名字源自傑拉德·溫斯坦利於17世紀領導的英國挖掘派[73]。這一團體尋求創立一個沒有貨幣和資本主義的小社會[74]。

哲學上的分歧[編輯]

生產積極性[編輯]

無政府共產主義者不接受「僱傭勞動是必要的,因為人的『人性』是懶惰和自私的」的觀點。他們經常指出,即使是所謂的「遊手好閒的富人」有時也能找到有用的事情做,儘管他們的所有需求其實都由他人的勞動滿足。無政府共產主義者一般不同意預先設定「人性」的信念,認為人類文化和行為在很大程度上是由社會化和生產方式決定的。包括彼得·阿列克謝耶維奇·克魯泡特金在內的許多無政府共產主義者認為人類的進化趨勢是趨向為了互利和生存而相互合作,而非趨向孤獨的競爭。克魯泡特金曾在著作中詳細論證了這一觀點[75]。

自由、工作與閒暇時間[編輯]

無政府共產主義者支持將共產主義作為確保一切人最大自由和福祉的一種手段。在這一角度上分析,無政府共產主義是一種平等主義哲學。

參見[編輯]

- 剝奪性積累

- 自治主義

- 無政府工團主義

- 共識民主

- 赤化

- 直接民主

- 自由人聯合體

- 馬赫諾運動

- 禮物經濟

- 暴動無政府主義

- 自由意志共產主義 (期刊)

- 自由意志馬克思主義

- 自由意志社會主義

- 內斯托爾·伊萬諾維奇·馬赫諾

- 新薩帕塔主義

- 綱領主義

- 拒絕工作

- 社會無政府主義

- 1936年西班牙革命

- 工人委員會

註釋[編輯]

參考文獻[編輯]

- ^ W Haixia. 无政府主义思想与乡村改造的实践回顾——从消去的无政府主义提取当代价值. Rural China. 2014-06-07, 11 (2): 301–327 [2021-02-20]. doi:10.1163/22136746-12341256.

- ^ "The Schism Between Individualist and Communist Anarchism" (頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館) by Wendy McElroy.

- ^ "Anarchist communism is also known as anarcho-communism, communist anarchism, or, sometimes, libertarian communism". "Anarchist communism - an introduction" by Jacques Roux.

- ^ 羽離子. 欧文的实验村——新兰那克的今昔. 《湖北民族學院學報(哲學社會科學版)》. 2003, 21 (3): 6–9 [2021-02-20]. doi:10.13501/j.cnki.42-1328/c.2003.03.002. (原始內容存檔於2019-06-15).

- ^ 自由共产主义简介. libcom.org. [2021-02-24]. (原始內容存檔於2021-01-24).

- ^ Price, Wayne (2002). "What is Anarchist Communism?" (頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館). The Anarchist Library. Retrieved 2019-08-04. "Instead, Kropotkin proposed that a large city, during a revolution, 「could organize itself on the lines of free communism; the city guaranteeing to every inhabitant dwelling, food, and clothing...in exchange for...five hour’s work; and...all those things which would be considered as luxuries might be obtained by everyone if he joins for the other half of the day all sorts of free associations....」 (p.p. 118–119)".

- ^ Bolloten, Burnett. The Spanish Civil War: Revolution and Counterrevolution. UNC Press Books. 1991: 65 [25 March 2011]. ISBN 978-0-8078-1906-7. (原始內容存檔於2020-08-01).

- ^ Price, Wayne (2002). "What is Anarchist Communism?" (頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館). The Anarchist Library. Retrieved 2019-08-04.

- ^ 反老孟; 黃璞葉. 黑命攸关|运动与暴力之辩:“糟得很”还是“好得很”?. 澎湃新聞. 2020-06-25 [2021-02-24]. (原始內容存檔於2021-04-23).

- ^ According to anarchist historian Max Nettlau, the first use of the term "libertarian communism" was in November 1880, when a French anarchist congress employed it to more clearly identify its doctrines. Nettlau, Max. A Short History of Anarchism. Freedom Press. 1996: 145. ISBN 978-0-900384-89-9.

- ^ "Anarchist communism is also known as anarcho-communism, communist anarchism, or, sometimes, libertarian communism". "Anarchist communism - an introduction" (頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館) by Libcom.org.

- ^ "The terms libertarian communism and anarchist communism thus became synonymous within the international anarchist movement as a result of the close connection they had in Spain (with libertarian communism becoming the prevalent term)". "Anarchist Communism & Libertarian Communism" by Gruppo Comunista Anarchico di Firenze. from "L'informatore di parte", No.4, October 1979, quarterly journal of the Gruppo Comunista Anarchico di Firenze (頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館).

- ^ "The 'Manifesto of Libertarian Communism' was written in 1953 by Georges Fontenis for the Federation Communiste Libertaire of France. It is one of the key texts of the anarchist-communist current". "Manifesto of Libertarian Communism" (頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館) by Georges Fontenis.

- ^ "In 1926 a group of exiled Russian anarchists in France, the Delo Truda (Workers' Cause) group, published this pamphlet. It arose not from some academic study but from their experiences in the 1917 Russian revolution". "The Organizational Platform of the Libertarian Communists" (頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館) by Delo Truda.

- ^ 於義永. 革命后的趋新:师复的无政府构想. 《社會科學前沿》. 2019年, 8 (4) [2021-02-18]. (原始內容存檔於2021-04-21).

- ^ 潘婉明. 在地 ∙ 跨域 ∙ 身体移动 ∙ 知识传播: 马来亚共产党史的再思考. 《華人研究國際學報》. 2011, 3 (2): 57–71 [2021-02-20]. doi:10.1142/S1793724811000162.

- ^ Kinna, Ruth. The Bloomsbury Companion to Anarchism. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. 2012-06-28: 329 [2021-02-17]. ISBN 978-1-4411-4270-2. (原始內容存檔於2021-01-15) (英語).

- ^ Hodges, Donald C. Sandino's Communism: Spiritual Politics for the Twenty-First Century. University of Texas Press. 2014-02-01: 3 [2021-02-17]. ISBN 978-0-292-71564-6. (原始內容存檔於2021-07-22) (英語).

- ^ Wetherly, Paul. Political Ideologies. Oxford University Press. 2017: 130, 137, 424 [2021-02-17]. ISBN 978-0-19-872785-9. (原始內容存檔於2021-07-22) (英語).

- ^ Iliopoulos, Christos. Nietzsche & Anarchism: An Elective Affinity and a Nietzschean reading of the December '08 revolt in Athens. Vernon Press. 2019-10-15: 35 [2021-02-17]. ISBN 978-1-62273-647-8. (原始內容存檔於2021-07-22) (英語).

- ^ Anarchist communism - an introduction. libcom.org. [2020-11-10]. (原始內容存檔於2021-01-23).

- ^ "The revolution abolishes private ownership of the means of production and distribution, and with it goes capitalistic business. Personal possession remains only in the things you use. Thus, your watch is your own, but the watch factory belongs to the people". Alexander Berkman. "What Is Communist Anarchism?" [1] (頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館).

- ^ Mayne, Alan James. From Politics Past to Politics Future: An Integrated Analysis of Current and Emergent Paradigms. Greenwood Publishing Group. 1999 [2010-09-20]. ISBN 978-0-275-96151-0. (原始內容存檔於2021-03-27).

- ^ Anarchism for Know-It-Alls By Know-It-Alls For Know-It-Alls, For Know-It-Alls. Filiquarian Publishing, LLC. 2008-01: 14 [2010-09-20]. ISBN 978-1-59986-218-7.[失效連結]

- ^ Fabbri, Luigi. "Anarchism and Communism." Northeastern Anarchist #4. 1922. 2002-10-13 (頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館).

- ^ Makhno, Mett, Arshinov, Valevski, Linski (Dielo Trouda). "The Organizational Platform of the Libertarian Communists". 1926. Constructive Section: available here (頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館).

- ^ Christopher Gray, Leaving the Twentieth Century, p. 88.

- ^ "Towards the creative Nothing" by (頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館) Renzo Novatore

- ^ Post-left anarcho-communist Bob Black after analysing insurrectionary anarcho-communist Luigi Galleani's view on anarcho-communism went as far as saying that "communism is the final fulfillment of individualism...The apparent contradiction between individualism and communism rests on a misunderstanding of both...Subjectivity is also objective: the individual really is subjective. It is nonsense to speak of "emphatically prioritizing the social over the individual,"...You may as well speak of prioritizing the chicken over the egg. Anarchy is a "method of individualization." It aims to combine the greatest individual development with the greatest communal unity."Bob Black. Nightmares of Reason (頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館).

- ^ "Modern Communists are more individualistic than Stirner. To them, not merely religion, morality, family and State are spooks, but property also is no more than a spook, in whose name the individual is enslaved - and how enslaved!...Communism thus creates a basis for the liberty and Eigenheit of the individual. I am a Communist because I am an Individualist. Fully as heartily the Communists concur with Stirner when he puts the word take in place of demand - that leads to the dissolution of property, to expropriation. Individualism and Communism go hand in hand". "Stirner: The Ego and His Own" (頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館). Max Baginski. Mother Earth. Vol. 2. No. 3 May 1907.

- ^ "Communism is the one which guarantees the greatest amount of individual liberty — provided that the idea that begets the community be Liberty, Anarchy...Communism guarantees economic freedom better than any other form of association, because it can guarantee wellbeing, even luxury, in return for a few hours of work instead of a day's work". "Communism and Anarchy" (頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館) by Peter Kropotkin.

- ^ "This other society will be libertarian communism, in which social solidarity and free individuality find their full expression, and in which these two ideas develop in perfect harmony". Organisational Platform of the Libertarian Communists (頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館) by Dielo Truda (Workers' Cause).

- ^ "I see the dichotomies made between individualism and communism, individual revolt and class struggle, the struggle against human exploitation and the exploitation of nature as false dichotomies and feel that those who accept them are impoverishing their own critique and struggle". "My Perspectives" 互聯網檔案館的存檔,存檔日期2010-12-02. by Willful Disobedience Vol. 2, No. 12.

- ^ L. Susan Brown, The Politics of Individualism, Black Rose Books (2002).

- ^ 35.0 35.1 35.2 L. Susan Brown, "Does Work Really Work?" (頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館).

- ^ 36.0 36.1 36.2 36.3 36.4 Robert Graham, Anarchism - A Documentary History of Libertarian Ideas - Volume One: From Anarchy to Anarchism (300CE to 1939), Black Rose Books, 2005

- ^ "Chapter 41: The Anarchists" (頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館) in The Great French Revolution 1789-1793 by Peter Kropotkin.

- ^ Nunzio Pernicone, Italian Anarchism 1864–1892, pp. 111-113, AK Press 2009.

- ^ 39.0 39.1 "Anarchist-Communism" by Alain Pengam: "This inability to break definitively with collectivism in all its forms also exhibited itself over the question of the workers' movement, which divided anarchist-communism into a number of tendencies."

- ^ "This process of education and class organization, more than any single factor in Spain, produced the collectives. And to the degree that the CNT-FAI (for the two organizations became fatally coupled after July 1936) exercised the major influence in an area, the collectives proved to be generally more durable, communist and resistant to Stalinist counterrevolution than other republican-held areas of Spain." Murray Bookchin (頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館). To Remember Spain: The Anarchist and Syndicalist Revolution of 1936]

- ^ Skirda, Alexandre (2004). Nestor Makhno: Anarchy's Cossack (頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館). AK Press. pp. 86. 236–238.

- ^ Murray Bookchin (頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館). To Remember Spain: The Anarchist and Syndicalist Revolution of 1936

- ^ Hinson, E. Glenn. The Early Church: Origins to the Dawn of the Middle Ages. 1996: 42–43.

- ^ Billings, Frank S. How shall the rich escape?. Arena Publishing. 1894: 42–43.

Jesusism, which is Communism, and not Christianity at all as the world accepts it...Jesusism is unadulterated communism, with a most destructive anarchistic tendency [耶穌主義就是共產主義,它根本不是世人所接受的,基督教的一種……耶穌主義是不折不扣的共產主義,且兼具破壞性的無政府主義傾向。]

- ^ Empson, Martin. A common treasury for all: Gerrard Winstanley's vision of utopia. International Socialism. No. 154. 2017-04-05 [2021-09-21]. (原始內容存檔於2021-10-07) (英語).

- ^ Campbell, Heather M. (編). The Britannica Guide to Political Science and Social Movements That Changed the Modern World. The Rosen Publishing Group. 2009: 127–129. ISBN 978-1615300624 (英語).

- ^ "The first Adam is the wisdom and power of flesh broke out and sate down in the chair of rule and dominion, in one part of mankind over another. And this is the beginner of particular interest, buying and selling the earth from one particular hand to another, saying, This is mine, upholding this particular propriety by a law of government of his own making, and thereby restraining other fellow creatures from seeking nourishment from their mother earth. So that though a man was bred up in a Land, yet he must not worke for himself where he would sit down. But from Adam; that is, for such a one that had bought part of the Land, or came to it by inheritance of his deceased parents, and called it his own Land: So that he that had no Land, was to work for those for small wages, that called the Land theirs; and thereby some are lifted up into the chair of tyranny, and others trod under the foot-stool of misery, as if the earth were made for a few, no for all men". Gerrard Winstanley (1649). The New Law of Righteousness (頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館).

- ^ Louis Armand, Baron de Lahontan (1703). New Voyages to North America. "Preface". Library of the University of Illinois. p. 11. "This I only mention by the bye, in this my Preface to the Reader, whom I pray the Heavens to Crown with Profperity, in preferving him from having any bufinefs to adjufl with mofi of the Miniflers of State, and Priefts; for let them be never fo faulty, they'll flill be faid to be in the right, till fuch time as Anarchy be introduc'd amongft us, as well as the Americans, among whom the forrycfl fellow thinks himfelf a better Man, than a Chancellor of France. Thefe People are happy in being fcreen'd from the tricks and fliifts of Miniflers, who are always Maflers where-ever they come. I envy the fiate of a poor Savage, who tramples upon Laws, and pays Homage to no Scepter. I wish I could fpend the reft of my Life in his Hutt, and fo be no longer expos'd to the chagrin of bending the knee to a fet of Men, that facrifice the publick good to their private intereft, and are born to plague honeft Men".

- ^ Louis Armand, Baron de Lahontan (1703). New Voyages to North America. "Introduction". Library of the University of Illinois. p. xxxv. "The vogue of the baron's book was immediate and widespread, and must have soon replenished his slender purse. In simple sentences, easily read and comprehended by the masses, Their Lahontan recounted not only his own adventures, and the important events that occurred beneath his eyes in the much-talked-of region of New France, but drew a picture of the simple delights of life in the wilderness, more graphic than had yet been presented to the European world. His idyllic account of manners and customs among the savages who dwelt in the heart of the American forest, or whose rude huts of bark or skin or matted reeds nestled by the banks of its far-reaching waterways, was a picture which fascinated the "average reader" in that romantic age, eager to learn of new lands and strange peoples. In the pages of Lahontan the child of nature was depicted as a creature of rare beauty of form, a rational being thinking deep thoughts on great subjects, but freed from the trammels and frets of civilization, bound by none of its restrictions, obedient only to the will and caprice of his own nature. In this American Arcady were no courts, laws, police, ministers of An American state, or other hampering paraphernalia of government; each man was a law unto himself, and did what seemed good in his own eyes. Here were no monks and priests, with their strictures and asceticisms, but a natural, sweetly-reasonable religion. Here no vulgar love of money pursued the peaceful native in his leafy home; without distinction of property, the rich man was he who might give most generously. Aboriginal marriage was no fettering life-covenant, but an arrangement pleasing the convenience of the contracting parties. Man, innocent and unadorned, passed his life in the pleasures of the chase, warring only in the cause of the nation, scorning the supposititious benefits of civilization, and free from its diseases, misery, sycophancy, and oppression. In short, the American wilderness was the seat of serenity and noble philosophy".

- ^ "The Agrarian law, or the partitioning of land, was the spontaneous demand of some unprincipled soldiers, of some towns moved more by their instinct than by reason. We lean towards something more sublime and more just: the common good or the community of property! No more individual property in land: the land belongs to no one. We demand, we want, the common enjoyment of the fruits of the land: the fruits belong to all". Sylvain Maréchal (1796). Manifesto of the Equals. (頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館) Marxist Internet Archive.

- ^ Joseph Déjacque, De l'être-humain mâle et femelle - Lettre à P.J. Proudhon par Joseph Déjacque (頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館) (in French)

- ^ "l'Echange", article in Le Libertaire no 6,1858-09-21, New York. [2] (頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館)

- ^ Nettlau, Max. A Short History of Anarchism. Freedom Press. 1996: 145. ISBN 978-0-900384-89-9.

- ^ Nettlau, Max. A Short History of Anarchism. Freedom Press. 1996: 162. ISBN 978-0-900384-89-9.

- ^ 引用錯誤:沒有為名為

Nunzio Pernicone pp. 111–13的參考文獻提供內容 - ^ 56.0 56.1 克魯泡特金, 彼得·阿列克謝耶維奇. 第十三章 集产主义的工钱制度. 面包与自由. 由巴, 金翻譯. 商務印書館. 1982 [2022-05-21]. (原始內容存檔於2021-11-06) (中文(簡體)).

總之,這便是集產主義者希望在社會革命後產生的組織。他們的原理,我們已經知道了,便是:生產機關為集合的財產,且以各人所費於生產的時間為標準,同時斟酌他的勞動的生產力而分配報酬。

- ^ Guillaume, James. Ideas on Social Organization. (原始內容存檔於2017-11-19).

- ^ Malatesta, Errico. "A Talk About Anarchist Communism Between Two Workers". 互聯網檔案館的存檔,存檔日期2010-01-10.. Retrieved 2020-08-05.

- ^ 克魯泡特金, 彼得·阿列克謝耶維奇. 第十一章 巴黎公社. 一个反抗者的话. 由畢, 修勺翻譯. 平明書店. 1948 [2022-05-21]. (原始內容存檔於2022-05-28) (中文(簡體)).

他們將以暴烈的充公廢除個人私有的財產,他們將以全體人民的名義,把前代勞動所積累下的全部社會財富收歸公有,他們將不再以一紙具文的法令,沒收社會資本佔有者的財產;他們將立即佔有他們,將立即使用他們並且成立使用的權利。

- ^ Peter Kropotkin, The Conquest of Bread, p145.

- ^ Marshall Shatz, Introduction to Kropotkin: The Conquest of Bread and Other Writings, Cambridge University Press 1995, p. xvi "Anarchist communism called for the socialization not only of production but of the distribution of goods: the community would supply the subsistence requirements of each individual member free of charge, and the criterion, 'to each according to his labor' would be superseded by the criterion 'to each according to his needs.'"

- ^ 克魯泡特金, 彼得·阿列克謝耶維奇. 第九章 奢侈的欲求. 面包与自由. 由巴, 金翻譯. 商務印書館. 1982 [2022-05-21]. (原始內容存檔於2021-08-18) (中文(簡體)).

他的物質的需要一經滿足,其他的可以說是帶有藝術性質的欲求,便會立刻發生。這樣的欲求種類很多,而且是因人而異的;社會愈文明,個性愈發達,則欲望的種類也愈多。

- ^ 克魯泡特金, 彼得·阿列克謝耶維奇. 第十三章 集产主义的工钱制度. 面包与自由. 由巴, 金翻譯. 商務印書館. 1982 [2022-05-21]. (原始內容存檔於2021-11-06) (中文(簡體)).

然而當我們承認房屋、田地、工廠不應再歸私人佔有,而應該成為公共的財產時,那麼怎樣還可以擁護這個工資的新形式——「勞動券」呢?

- ^ The Place of Anarchism in the Evolution of Socialist Thought

- ^ 克魯泡特金, 彼得·阿列克謝耶維奇. 第四章 充公. 面包与自由. 由巴, 金翻譯. 商務印書館. 1982 [2022-05-21]. (原始內容存檔於2021-08-18) (中文(簡體)).

假定現在有一個居民不過數百萬的社會從事於農業及種種的工業——例如,巴黎和塞納—瓦茲省。假定這個社會裏的所有的兒童都學習用自己的腦和手勞動。除開那些從事教育兒童的婦人而外,凡是成年的人,從二十歲或二十二歲起,到四十五歲或五十歲止,每天都應該勞動五小時而且還要從事一種這城裏所認為必需的職業,但任其選擇任何部門。這樣的社會才能夠保證其中一切人的安樂。比今日中產階級所享受到的安樂還要實在些。並且這個社會裏每個工人至少每天有五小時的時間用在科學、藝術以及那些不便歸在必需品的項下的個人的欲求(在人類生產力增加的時候,這些東西也成為必需品,不再是奢侈難得的東西)上面的。

- ^ 克魯泡特金, 彼得·阿列克謝耶維奇. 第八章 生产的方法与手段. 面包与自由. 由巴, 金翻譯. 商務印書館. 1982 [2022-05-21]. (原始內容存檔於2022-06-09) (中文(簡體)).

假定現在有一個居民不過數百萬的社會從事於農業及種種的工業——例如,巴黎和塞納—瓦茲省。假定這個社會裏的所有的兒童都學習用自己的腦和手勞動。除開那些從事教育兒童的婦人而外,凡是成年的人,從二十歲或二十二歲起,到四十五歲或五十歲止,每天都應該勞動五小時而且還要從事一種這城裏所認為必需的職業,但任其選擇任何部門。這樣的社會才能夠保證其中一切人的安樂。比今日中產階級所享受到的安樂還要實在些。並且這個社會裏每個工人至少每天有五小時的時間用在科學、藝術以及那些不便歸在必需品的項下的個人的欲求(在人類生產力增加的時候,這些東西也成為必需品,不再是奢侈難得的東西)上面的。

- ^ Propaganda by the deed [行動宣傳]. Workers Solidarity. No. 55. 1998-10. (原始內容存檔於2018-06-05).

- ^ Alexander Berkman. What Is Communist Anarchism? [3] (頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館)

- ^ Kropotkin, Peter. "The Collectivist Wage System". The Conquest of Bread, G. P. Putnam's Sons, New York and London, 1906, Chapter 13, Section 4

- ^ Alexander Berkman. What is Anarchism?, p. 217

- ^ 徐, 雪晴. 10 个词,帮你了解美国 50 年前那个“除了爱就没别的了”的夏天(一). 好奇心日報. 2017-09-17 [2022-05-21]. (原始內容存檔於2022-06-03).

- ^ Lytle, Mark Hamilton. America's Uncivil Wars: The Sixties Era from Elvis to the Fall of Richard Nixon. Oxford University Press. 2005: 213, 215 [2017-06-29]. ISBN 978-0190291846. (原始內容存檔於2021-04-27).

- ^ Overview: who were (are) the Diggers?. The Digger Archives. [2007-06-17]. (原始內容存檔於2018-10-04).

- ^ Gail Dolgin; Vicente Franco. American Experience: The Summer of Love. PBS. 2007 [2007-04-23]. (原始內容存檔於2017-03-25).

- ^ Peter Kropotkin Mutual Aid: A Factor in Evolution [4] (頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館)

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|