阿法南方古猿:修订间差异

小无编辑摘要 |

|||

| 第1行: | 第1行: | ||

{{Taxobox |

|||

#REDIRECT [[露西]] |

|||

| color = pink |

|||

| name = 阿法南方古猿 |

|||

| fossil_range = [[Pliocene]] |

|||

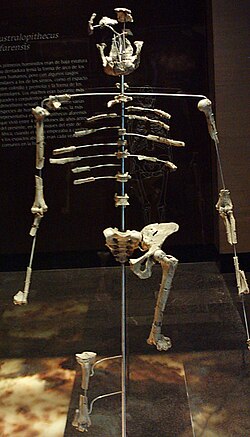

| image = Lucy_Mexico.jpg |

|||

| image_width = 250px |

|||

| image_caption = Picture of [[Lucy (Australopithecus)|Lucy]] remains replica, [[Museo Nacional de Antropología]], [[Mexico City]] |

|||

| regnum = [[動物界]] Animalia |

|||

| phylum = [[脊索動物門]] Chordata |

|||

| classis = [[哺乳動物綱]] Mammalia |

|||

| ordo = [[靈長目]] Primates |

|||

| familia = [[人科]] Hominidae |

|||

| subfamilia = [[人亞科]] Homininae |

|||

| genus = [[南方古猿屬]] ''Australopithecus'' |

|||

| species = '''阿法南方古猿 ''A. afarensis''''' |

|||

| binomial = †''Australopithecus afarensis'' |

|||

| binomial_authority = [[Donald Johanson|Johanson]] & [[Timothy White (anthropologist)|White]], [[1978年|1978]] |

|||

}} |

|||

'''阿法南方古猿'''(''Australopithecus afarensis''),又名'''南方古猿阿法種''' is an extinct [[hominid]] which lived between 3.9 and 2.9 million years ago. In common with the younger ''[[Australopithecus africanus]]'', ''A. afarensis'' was slenderly built. From analysis it has been thought that ''A. afarensis'' was ancestral to both the genus ''[[Australopithecus]]'' and the genus ''[[Homo (genus)|Homo]]'', which includes the modern human species, ''[[Homo sapiens]]''.<ref name=lucy>{{harvnb|Johanson|1981|p=283-297}}</ref><ref name="cambridge">Jones, S. Martin; & R. Pilbeam (ed.) (2004). ''The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Human Evolution'' (8th ed.).[[Cambridge University Press]]. ISBN 0-521-46786-1</ref>. |

|||

== Localities == |

|||

''Australopithecus afarensis'' fossils have only been discovered within [[eastern Africa]]. Despite Laetoli being the [[Type locality (geology)|type locality]] for ''A. afarensis'', the most extensive remains assigned to this species are found in Hadar, [[Ethiopia]], including the famous "Lucy" partial skeleton and the "First Family" found at the A.L. 333 locality. Other localities bearing ''A. afarensis'' remains include Omo, Maka, Fejej and Belohdelie in [[Ethiopia]], and [[Koobi Fora]] and Lothagam in [[Kenya]]. |

|||

==身體特徵== |

|||

===Craniodental features and Brain Size=== |

|||

Compared to the modern and extinct great [[apes]], ''A. afarensis'' has reduced canines and molars, although they are still relatively larger than in modern humans. ''A. afarensis'' also had a relatively small [[Neuroscience and intelligence|brain size]] (~380-430cm³) and a prognathic (i.e. projecting anteriorly) face. |

|||

The image of a [[biped]]al hominin with a small brain and primitive face was quite a revelation to the paleoanthropological world at the time. This was due to the earlier belief that an increase in brain size was the first major hominin adaptive shift. Before the discoveries of ''A. afarensis'' in the 1970s, it was widely thought that an increase in brain size preceded the shift to bipedal locomotion. This was mainly due to the fact that the oldest known hominins at the time had relatively large brains (e.g KNM-ER 1470, [[Homo rudolfensis]], which was found just a few years before Lucy and had a cranial capacity of ~800cm³). |

|||

===雙足行走=== |

|||

[[Image:Australopithecusafarensis reconstruction.jpg|left|thumb|200px|Australopithecus afarensis skull reconstruction, displayed at Museum of Man, [[San Diego, California]].]] |

|||

There is considerable debate regarding the locomotor behaviour of ''A. afarensis''. Some believe that ''A. afarensis'' was almost exclusively bipedal, while others believe that the creatures were partly arboreal. The anatomy of the hands, feet and shoulder joints in many ways favour the latter interpretation. The curvature of the finger and toe bones ([[phalanx bones|Phalanges]]) approaches that of modern-day apes, and is most likely reflective of their ability to efficiently grasp branches and climb. The presence of a wrist-locking mechanism might suggest that they were knuckle-walkers. The shoulder joint is also orientated more cranially (i.e. towards the skull) than in modern humans. Combined with the relatively long arms ''A. afarensis'' are thought to have had, this is thought by many to be reflective of a heightened ability to use the arm above the head in climbing behaviour. Furthermore, scans of the skulls reveal a canal and bony labyrinth morphology, which some suggest is not conducive to proper bipedal locomotion. |

|||

However, there are also a number of traits in the ''A. afarensis'' skeleton which strongly reflect bipedalism. In overall anatomy, the pelvis is far more human-like than ape-like. The iliac blades are short and wide, the sacrum is wide and positioned directly behind the hip joint, and there is clear evidence of a strong attachment for the [[Rectus femoris|knee extensors]]. While the [[pelvis]] is not wholly human-like (being markedly wide with flared with laterally orientated iliac blades), these features point to a structure that can be considered radically remodeled to accommodate a significant degree of [[bipedalism]] in the animals' locomotor repertoire. Importantly, the [[femur]] also angles in toward the [[knee]] from the [[hip]]. This trait would have allowed the [[foot]] to have fallen closer to the midline of the body, and is a strong indication of habitual bipedal locomotion. Along with [[human]]s, present day [[orangutan]]s and [[spider monkey]]s possess this same feature. The feet also feature [[adducted]] big toes, making it difficult if not impossible to grasp branches with the [[hindlimb]]s. The loss of a grasping hindlimb also increases the risk of an infant being dropped or falling, as primates typically hold onto their mothers while the mother goes about her daily business. Without the second set of grasping limbs, the infant cannot maintain as strong a grip, and likely had to be held with help from the mother. The problem of holding the infant would be multiplied if the mother also had to climb trees. The [[ankle]] joint of ''A. afarensis'' is also markedly human-like.{{Fact|date=February 2007}} |

|||

Computer simulations using [[Dynamic modeling|dynamic modelling]] of the skeleton's [[Moment of inertia|inertial properties]] and [[kinematics]] have indicated that ''A. afarensis'' was able to walk in the same way modern humans walk, with a normal erect gait or with bent hips and knees, but could not walk in the same way as [[chimpanzee]]s. The upright gait would have been much more efficient than the bent knee and hip walking, which would have taken twice as much energy.<ref name=bbc>{{cite web |url=http://www.bbc.co.uk/sn/prehistoric_life/human/human_evolution/mother_of_man1.shtml |title=BBC - Science & Nature - The evolution of man |accessdate=2007-11-01 |work=Mother of man - 3.2 million years ago }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.liv.ac.uk/premog/premog-research.htm#backevidence |title=PREMOG - Research |accessdate=2007-11-01 |date= [[18 May]] [[2007]] |work=How Lucy walked |publisher=Primate Evolution & Morphology Group (PREMOG), the Department of Human Anatomy and Cell Biology, the School of Biomedical Sciences at the [[University of Liverpool]] }}</ref> It appears probable that ''A. afarensis'' was quite an efficient bipedal walker over short distances, and the spacing of the footprints at [[Laetoli]] indicates that they were walking at 1.0 m/s or above, which matches human small-town walking speeds.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.liv.ac.uk/premog/premog-sup-info-Laetoli.htm |title=PREMOG - Supplementry Info |accessdate=2007-11-01 |date= [[18 May]] [[2007]] |work=The Laetoli Footprint Trail: 3D reconstruction from texture; archiving, and reverse engineering of early hominin gait |publisher=Primate Evolution & Morphology Group (PREMOG), the Department of Human Anatomy and Cell Biology, the School of Biomedical Sciences at the [[University of Liverpool]] }}</ref> |

|||

It is commonly thought that upright bipedal walking evolved from knuckle-walking with bent legs, in the manner used by chimpanzees and [[gorilla]]s to move around on the ground, but fossils such as [[Orrorin tugenensis]] indicate bipedalism around 5 to 8 million years ago, in the same general period where genetic studies suggest the lineage of chimpanzees and humans diverged. Modern apes and their fossil ancestors show skeletal adaptations to an upright posture used in tree climbing, and it has been proposed that that upright, straight-legged walking originally evolved as an adaptation to tree-dwelling. Studies of modern [[orangutan]]s in [[Sumatra]] have shown these apes using four legs when walking on large stable branches and when swinging underneath slightly smaller branches, but are bipedal and maintain their legs very straight when using multiple small flexible branches under 4 cm. in diameter while also using their arms for balance and additional support. This enables them to get nearer to the edge of the tree canopy to grasp fruit or cross to another tree. |

|||

Climate changes around 11 to 12 million years ago affected forests in East and Central Africa, establishing periods where openings prevented travel through the tree canopy, and during these times ancestral hominids could have adapted the upright walking behaviour for ground travel, while the ancestors of gorillas and chimpanzees became more specialised in climbing vertical tree trunks or lianas with a bent hip and bent knee posture, ultimately leading them to use the related knuckle-walking posture for ground travel. This would lead to ''A. afarensis'' usage of upright bipedalism for ground travel, while still having arms well adapted for climbing smaller trees. However, chimpanzees and gorillas are the closest living relatives to humans, and share anatomical features including a fused wrist bone which may also suggest knuckle-walking by human ancestors.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://education.guardian.co.uk/higher/research/story/0,,2093002,00.html |title=New theory rejects popular view of man's evolution - Research - EducationGuardian.co.uk |accessdate=2007-11-05 |author=Ian Sample, science correspondent |date=June 1, 2007 }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/sci/tech/6709627.stm |title=BBC NEWS - Science/Nature - Upright walking 'began in trees' |accessdate=2007-11-05 |date=31 May 2007 }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.liv.ac.uk/premog/premog-sup-info-SCIENCE.htm |title=PREMOG - Supplementry Info |accessdate=2007-11-01 |author= Thorpe S.K.S.|authorlink= |coauthors=Holder R.L., and Crompton R.H. |date= [[24 May]] [[2007]] |work=Origin of Human Bipedalism As an Adaptation for Locomotion on Flexible Branches |publisher=Primate Evolution & Morphology Group (PREMOG), the Department of Human Anatomy and Cell Biology, the School of Biomedical Sciences at the [[University of Liverpool]] }}</ref> Other studies suggest that an upright spine and a primarily vertical body plan in primates dates back to ''[[Morotopithecus bishopi]]'' in the [[Early Miocene]] of 21.6 million years ago<ref>{{cite web |url=http://blog.oup.com/2007/12/human/#more-1425 |title=Redefining the word “Human” – Do Some Apes Have Human Ancestors? : OUPblog |accessdate=2007-12-27 |author=Aaron G. Filler |date=December 24, 2007 }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.plosone.org/article/fetchArticle.action?articleURI=info:doi/10.1371/journal.pone.0001019 |title=PLoS ONE: Homeotic Evolution in the Mammalia: Diversification of Therian Axial Seriation and the Morphogenetic Basis of Human Origins |accessdate=2007-12-27 |author=Aaron G. Filler |date=October 10, 2007 }}</ref> |

|||

===Social characteristics=== |

|||

[[Image:Lucyreconstruction.jpg|right|thumb|200px|Full reconstruction of Lucy on display at Museum of Man, [[San Diego, California]].]] |

|||

It is difficult to predict the social behaviour of extinct fossil species. However, the social structure of modern apes and monkeys can be anticipated to some extent by the average range of body size between males and females (known as [[sexual dimorphism]]). Although there is considerable debate over how large the degree of sexual dimorphism was between males and females of ''A. afarensis'', it is likely that males were relatively larger than females. If observations on the relationship between sexual dimorphism and social group structure from modern great apes are applied to ''A. afarensis'' then these creatures most likely lived in small family groups containing a single dominant male and a number of breeding females.<ref name="cambridge"/> |

|||

There are no known stone-tools associated with ''A. afarensis'', and the present archeological record of stone artifacts only dates back to approximately 2.5 million years ago.<ref name="cambridge"/> |

|||

===Lineage questions=== |

|||

In 1977 [[Donald Johanson]] and his colleague [[Tim White (anthropologist)|Tim White]] carried out detailed [[morphology (biology)|morphological]] studies on their finds to date, including both [[Lucy (Australopithecus)|Lucy]] and the "First Family" fossils. They compared the fossils to [[chimpanzee]], [[gorilla]] and modern human specimens, and casts of extinct [[hominid]] fossils, with particular attention to jaws and dental arcades, and found that their fossils were somewhere between humans and apes, possibly closer to apes, though with essentially human bodies. They reached the conclusion that it could not be classified in the genus ''[[Homo (genus)|Homo]]'' and should be in the genus ''[[Australopithecus]]'' as the new species ''Australopithecus afarensis''. They believed that this extinct [[hominid]] would prove to be ancestral to ''[[Australopithecus africanus]]'' and ''[[Australopithecus robustus]]'' as well as to the genus ''Homo'' which includes the modern human species, ''[[Homo sapiens]]'',<ref>{{harvnb|Johanson|1981|p=265-266, 278-279, 283-297}}</ref> and this conclusion was widely accepted.<ref name="cambridge">Jones, S. Martin; & R. Pilbeam (ed.) (2004). ''The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Human Evolution'' (8th ed.).[[Cambridge University Press]]. ISBN 0-521-46786-1</ref> However, in 2006 scientists Yoel Rak, Avishag Ginzburg, and Eli Geffen carried out a morphological analysis which found that the [[Ramus of the mandible|mandibular ramus]] (jawbone) of ''australopithecus afarensis'' specimen A. L. 822-1 discovered in 2002 closely matches that of a gorilla, and from further studies they concluded that "australopithecus afarensis" is more likely a member of the [[robust australopithecines]] branch of the hominid evolutionary tree and so not a direct ancestor of man. They concluded that ''[[Ardipithecus|Ardipithecus ramidus]]'' discovered by White and colleagues in the 1990s is a more likely ancestor of the human [[clade]].<ref name=gor1>{{cite web |url=http://www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/104/16/6568 |title=From the Cover: Gorilla-like anatomy on Australopithecus afarensis mandibles suggests Au. afarensis link to robust australopiths -- Rak et al. 104 (16): 6568 -- Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences |accessdate=2007-10-19 |author=Yoel Rak |authorlink= |coauthors=Avishag Ginzburg and Eli Geffen |date=April 17, 2007 }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0606454104/DC1 |title=From the Cover: Gorilla-like anatomy on Australopithecus afarensis mandibles suggests Au. afarensis link to robust australopiths -- Rak et al. 104 (16): 6568 Data Supplement - HTML Page - index.htslp -- Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences |accessdate=2007-10-19 |author=Yoel Rak |authorlink= |coauthors=Avishag Ginzburg and Eli Geffen |date=April 17, 2007 }}</ref> |

|||

==著名化石== |

|||

===Type specimen=== |

|||

The [[Type (zoology)|type specimen]] for ''A. afarensis'' is [[LH 4]], an adult mandible from the site of [[Laetoli]], [[Tanzania]]. |

|||

===AL 129-1=== |

|||

{{main|AL 129-1}} |

|||

The first ''A. afarensis'' knee joint was discovered in November 1973 by [[Donald Johanson]] as part of a team involving [[Maurice Taieb]], [[Yves Coppens]] and [[Tim White (anthropologist)|Tim White]] in the [[Middle Awash]] of [[Ethiopia]]'s [[Afar Depression]]. |

|||

===Lucy=== |

|||

{{main|Lucy (Australopithecus)}} |

|||

The first ''A. afarensis'' [[skeleton]] was discovered on [[November 24]], [[1974]] by [[Tom Gray (anthropologist)|Tom Gray]] in the company of [[Donald Johanson]], as part of a team involving [[Maurice Taieb]], [[Yves Coppens]] and [[Tim White (anthropologist)|Tim White]] in the [[Middle Awash]] of [[Ethiopia]]'s [[Afar Depression]]. |

|||

===Site 333=== |

|||

[[Michael Bush (anthropologist)|Michael Bush]], one of Don Johanson's students, made another major discovery in 1975: near Lucy, on the other side of the hill, he found the "First Family", including 200 fragments of ''A. afarensis''. The site of the findings is now known as "''site 333''", by a count of fossil fragments uncovered, such as teeth and pieces of jaw. 13 individuals were uncovered and all were adults, with no injuries caused by carnivores. All 13 individuals seemed to have died at the same time, thus Johanson concluded that they might have been killed instantly from a flash flood. |

|||

===Selam=== |

|||

{{main|Selam (Australopithecus)}} |

|||

On [[September 20]] [[2006]], ''[[Scientific American]]'' magazine presented the findings of a dig in Dikika, [[Ethiopia]], a few miles from the place where Lucy was found. The recovered skeleton of a 3-year-old ''A. afarensis'' girl comprises almost the entire skull and torso, and most parts of the limbs. The features of the skeleton suggest adaptation to walking upright ([[bipedalism]]) as well as tree-climbing, features that match the skeletal features of Lucy and fall midway between human and humanoid ape anatomy. "Baby Lucy" has officially been named "''Selam''" (meaning ''peace'' in most [[Ethiopian languages]]). [http://www.sciam.com/article.cfm?chanID=sa003&articleID=00076C1D-62D1-1511-A2D183414B7F0000] |

|||

===Others=== |

|||

*[[AL 200-1]] |

|||

*[[AL 129-1]] |

|||

*[[AL 444]] |

|||

==Related work== |

|||

Further findings at Afar, including the many hominin bones in ''site 333'', produced more bones of concurrent date, and led to Johanson and White's eventual argument that the Koobi Fora hominins were concurrent with the Afar hominins. In other words, Lucy was not unique in evolving bipedalism and a flat face. |

|||

Recently, an entirely new species has been discovered, called ''[[Kenyanthropus platyops]]'', however the cranium [[KNM WT 40000]] has a much distorted matrix making it hard to distinguish (however a flat face is present). This had many of the same characteristics as Lucy, but is possibly an entirely different genus. |

|||

Another species, called ''[[Ardipithecus|Ardipithecus ramidus]]'', was found by White and colleagues in the 1990s. This was fully bipedal, yet appears to have been contemporaneous with a woodland environment, and, more importantly, contemporaneous with ''Australopithecus afarensis''. Scientists have not yet been able to draw an estimation of the [[cranial capacity]] of ''Ar. ramidus'' as only small jaw and leg fragments have been discovered thus far. |

|||

==參考== |

|||

{{reflist}} |

|||

*[[BBC]] - ''Dawn of Man'' (2000) by Robin Mckie| ISBN 0-7894-6262-1 |

|||

*{{cite book|title = Atlas of World History|author=Barraclough, G.|edition = 3rd edition|editor=Stone, N. (ed.)|year=1989|publisher=Times Books Limited|id=ISBN 0-7230-0304-1 }} |

|||

*[http://www.mnh.si.edu/anthro/humanorigins/ha/afar.html Australopithecus afarensis] from ''The Human Origins Program at the [[Smithsonian Institution]]'' |

|||

*{{cite book|title = Encyclopedia of human evolution and prehistory|edition = 2nd Edition|editor= Delson, E., I. Tattersall, J.A. Van Couvering & A.S. Brooks (eds.)|year=2000|publisher= Garland Publishing, New York|id=ISBN 0-8153-1696-8 }} |

|||

* {{Harvard reference|Surname1= Johanson |Given1= Donald |Authorlink1=Donald C. Johanson|Surname2= Edey |Given2= Maitland |Authorlink2=Maitland Edey||Year=1981|Title=Lucy, the Beginnings of Humankind|publication-place=St Albans|Publisher=Granada|ID=ISBN 0-586-08437-1}} |

|||

==外部連結== |

|||

*[http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v440/n7086/abs/nature04629.html Asa Issie, Aramis and the origin of Australopithecus] |

|||

*[http://www.amnh.org/exhibitions/atapuerca/africa/lucy.php Lucy at the American Museum of Natural History in Manhattan] |

|||

*[http://www.asu.edu/clas/iho/lucy.html Lucy at the Institute of Human Origins at Arizona State University] |

|||

*[http://www.geocities.com/palaeoanthropology/Aafarensis.html Asfarensis] |

|||

*[http://www.somso.de/english/anatomie/stammesgeschichte.htm Anthropological skulls and reconstructions] |

|||

*[http://www.becominghuman.org/ Becoming Human: Paleoanthropology, Evolution and Human Origins] |

|||

*[http://www9.nationalgeographic.com/ngm/dikikababy/ ''National Geographic'' "Dikika baby"] |

|||

*[http://www.mnsu.edu/emuseum/biology/humanevolution/afarensis.html MNSU] |

|||

*[http://www.archaeologyinfo.com/australopithecusafarensis.htm Archaeology Info] |

|||

*[http://www.mnh.si.edu/anthro/humanorigins/ha/afar.html Smithsonian] |

|||

[[Category:早期人類]] |

|||

[[Category:南方古猿]] |

|||

[[am:ድንቅ ነሽ]] |

|||

[[ar:لوسي (علم الإنسان)]] |

|||

[[ca:Australopithecus afarensis]] |

|||

[[da:Lucy (abemenneske)]] |

|||

[[de:Australopithecus afarensis]] |

|||

[[en:Australopithecus afarensis]] |

|||

[[et:Australopithecus afarensis]] |

|||

[[es:Australopithecus afarensis]] |

|||

[[eo:Lucy]] |

|||

[[eu:Australopithecus afarensis]] |

|||

[[fr:Australopithecus afarensis]] |

|||

[[gl:Australopithecus afarensis]] |

|||

[[it:Australopithecus afarensis]] |

|||

[[he:לוסי]] |

|||

[[ja:アウストラロピテクス・アファレンシス]] |

|||

[[lb:Australopithecus afarensis]] |

|||

[[nl:Australopithecus afarensis]] |

|||

[[pl:Australopithecus afarensis]] |

|||

[[pt:Australopithecus afarensis]] |

|||

[[ru:Австралопитек афарский]] |

|||

[[simple:Australopithecus afarensis]] |

|||

[[sl:Lucy]] |

|||

[[fi:Australopithecus afarensis]] |

|||

[[sv:Australopithecus afarensis]] |

|||

2008年2月21日 (四) 00:14的版本

| 阿法南方古猿 化石時期: Pliocene | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||

| 科學分類 | ||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||

| 二名法 | ||||||||||||||||

| †Australopithecus afarensis Johanson & White, 1978 |

阿法南方古猿(Australopithecus afarensis),又名南方古猿阿法種 is an extinct hominid which lived between 3.9 and 2.9 million years ago. In common with the younger Australopithecus africanus, A. afarensis was slenderly built. From analysis it has been thought that A. afarensis was ancestral to both the genus Australopithecus and the genus Homo, which includes the modern human species, Homo sapiens.[1][2].

Localities

Australopithecus afarensis fossils have only been discovered within eastern Africa. Despite Laetoli being the type locality for A. afarensis, the most extensive remains assigned to this species are found in Hadar, Ethiopia, including the famous "Lucy" partial skeleton and the "First Family" found at the A.L. 333 locality. Other localities bearing A. afarensis remains include Omo, Maka, Fejej and Belohdelie in Ethiopia, and Koobi Fora and Lothagam in Kenya.

身體特徵

Craniodental features and Brain Size

Compared to the modern and extinct great apes, A. afarensis has reduced canines and molars, although they are still relatively larger than in modern humans. A. afarensis also had a relatively small brain size (~380-430cm³) and a prognathic (i.e. projecting anteriorly) face.

The image of a bipedal hominin with a small brain and primitive face was quite a revelation to the paleoanthropological world at the time. This was due to the earlier belief that an increase in brain size was the first major hominin adaptive shift. Before the discoveries of A. afarensis in the 1970s, it was widely thought that an increase in brain size preceded the shift to bipedal locomotion. This was mainly due to the fact that the oldest known hominins at the time had relatively large brains (e.g KNM-ER 1470, Homo rudolfensis, which was found just a few years before Lucy and had a cranial capacity of ~800cm³).

雙足行走

There is considerable debate regarding the locomotor behaviour of A. afarensis. Some believe that A. afarensis was almost exclusively bipedal, while others believe that the creatures were partly arboreal. The anatomy of the hands, feet and shoulder joints in many ways favour the latter interpretation. The curvature of the finger and toe bones (Phalanges) approaches that of modern-day apes, and is most likely reflective of their ability to efficiently grasp branches and climb. The presence of a wrist-locking mechanism might suggest that they were knuckle-walkers. The shoulder joint is also orientated more cranially (i.e. towards the skull) than in modern humans. Combined with the relatively long arms A. afarensis are thought to have had, this is thought by many to be reflective of a heightened ability to use the arm above the head in climbing behaviour. Furthermore, scans of the skulls reveal a canal and bony labyrinth morphology, which some suggest is not conducive to proper bipedal locomotion.

However, there are also a number of traits in the A. afarensis skeleton which strongly reflect bipedalism. In overall anatomy, the pelvis is far more human-like than ape-like. The iliac blades are short and wide, the sacrum is wide and positioned directly behind the hip joint, and there is clear evidence of a strong attachment for the knee extensors. While the pelvis is not wholly human-like (being markedly wide with flared with laterally orientated iliac blades), these features point to a structure that can be considered radically remodeled to accommodate a significant degree of bipedalism in the animals' locomotor repertoire. Importantly, the femur also angles in toward the knee from the hip. This trait would have allowed the foot to have fallen closer to the midline of the body, and is a strong indication of habitual bipedal locomotion. Along with humans, present day orangutans and spider monkeys possess this same feature. The feet also feature adducted big toes, making it difficult if not impossible to grasp branches with the hindlimbs. The loss of a grasping hindlimb also increases the risk of an infant being dropped or falling, as primates typically hold onto their mothers while the mother goes about her daily business. Without the second set of grasping limbs, the infant cannot maintain as strong a grip, and likely had to be held with help from the mother. The problem of holding the infant would be multiplied if the mother also had to climb trees. The ankle joint of A. afarensis is also markedly human-like.[來源請求]

Computer simulations using dynamic modelling of the skeleton's inertial properties and kinematics have indicated that A. afarensis was able to walk in the same way modern humans walk, with a normal erect gait or with bent hips and knees, but could not walk in the same way as chimpanzees. The upright gait would have been much more efficient than the bent knee and hip walking, which would have taken twice as much energy.[3][4] It appears probable that A. afarensis was quite an efficient bipedal walker over short distances, and the spacing of the footprints at Laetoli indicates that they were walking at 1.0 m/s or above, which matches human small-town walking speeds.[5]

It is commonly thought that upright bipedal walking evolved from knuckle-walking with bent legs, in the manner used by chimpanzees and gorillas to move around on the ground, but fossils such as Orrorin tugenensis indicate bipedalism around 5 to 8 million years ago, in the same general period where genetic studies suggest the lineage of chimpanzees and humans diverged. Modern apes and their fossil ancestors show skeletal adaptations to an upright posture used in tree climbing, and it has been proposed that that upright, straight-legged walking originally evolved as an adaptation to tree-dwelling. Studies of modern orangutans in Sumatra have shown these apes using four legs when walking on large stable branches and when swinging underneath slightly smaller branches, but are bipedal and maintain their legs very straight when using multiple small flexible branches under 4 cm. in diameter while also using their arms for balance and additional support. This enables them to get nearer to the edge of the tree canopy to grasp fruit or cross to another tree.

Climate changes around 11 to 12 million years ago affected forests in East and Central Africa, establishing periods where openings prevented travel through the tree canopy, and during these times ancestral hominids could have adapted the upright walking behaviour for ground travel, while the ancestors of gorillas and chimpanzees became more specialised in climbing vertical tree trunks or lianas with a bent hip and bent knee posture, ultimately leading them to use the related knuckle-walking posture for ground travel. This would lead to A. afarensis usage of upright bipedalism for ground travel, while still having arms well adapted for climbing smaller trees. However, chimpanzees and gorillas are the closest living relatives to humans, and share anatomical features including a fused wrist bone which may also suggest knuckle-walking by human ancestors.[6][7][8] Other studies suggest that an upright spine and a primarily vertical body plan in primates dates back to Morotopithecus bishopi in the Early Miocene of 21.6 million years ago[9][10]

Social characteristics

It is difficult to predict the social behaviour of extinct fossil species. However, the social structure of modern apes and monkeys can be anticipated to some extent by the average range of body size between males and females (known as sexual dimorphism). Although there is considerable debate over how large the degree of sexual dimorphism was between males and females of A. afarensis, it is likely that males were relatively larger than females. If observations on the relationship between sexual dimorphism and social group structure from modern great apes are applied to A. afarensis then these creatures most likely lived in small family groups containing a single dominant male and a number of breeding females.[2]

There are no known stone-tools associated with A. afarensis, and the present archeological record of stone artifacts only dates back to approximately 2.5 million years ago.[2]

Lineage questions

In 1977 Donald Johanson and his colleague Tim White carried out detailed morphological studies on their finds to date, including both Lucy and the "First Family" fossils. They compared the fossils to chimpanzee, gorilla and modern human specimens, and casts of extinct hominid fossils, with particular attention to jaws and dental arcades, and found that their fossils were somewhere between humans and apes, possibly closer to apes, though with essentially human bodies. They reached the conclusion that it could not be classified in the genus Homo and should be in the genus Australopithecus as the new species Australopithecus afarensis. They believed that this extinct hominid would prove to be ancestral to Australopithecus africanus and Australopithecus robustus as well as to the genus Homo which includes the modern human species, Homo sapiens,[11] and this conclusion was widely accepted.[2] However, in 2006 scientists Yoel Rak, Avishag Ginzburg, and Eli Geffen carried out a morphological analysis which found that the mandibular ramus (jawbone) of australopithecus afarensis specimen A. L. 822-1 discovered in 2002 closely matches that of a gorilla, and from further studies they concluded that "australopithecus afarensis" is more likely a member of the robust australopithecines branch of the hominid evolutionary tree and so not a direct ancestor of man. They concluded that Ardipithecus ramidus discovered by White and colleagues in the 1990s is a more likely ancestor of the human clade.[12][13]

著名化石

Type specimen

The type specimen for A. afarensis is LH 4, an adult mandible from the site of Laetoli, Tanzania.

AL 129-1

The first A. afarensis knee joint was discovered in November 1973 by Donald Johanson as part of a team involving Maurice Taieb, Yves Coppens and Tim White in the Middle Awash of Ethiopia's Afar Depression.

Lucy

The first A. afarensis skeleton was discovered on November 24, 1974 by Tom Gray in the company of Donald Johanson, as part of a team involving Maurice Taieb, Yves Coppens and Tim White in the Middle Awash of Ethiopia's Afar Depression.

Site 333

Michael Bush, one of Don Johanson's students, made another major discovery in 1975: near Lucy, on the other side of the hill, he found the "First Family", including 200 fragments of A. afarensis. The site of the findings is now known as "site 333", by a count of fossil fragments uncovered, such as teeth and pieces of jaw. 13 individuals were uncovered and all were adults, with no injuries caused by carnivores. All 13 individuals seemed to have died at the same time, thus Johanson concluded that they might have been killed instantly from a flash flood.

Selam

On September 20 2006, Scientific American magazine presented the findings of a dig in Dikika, Ethiopia, a few miles from the place where Lucy was found. The recovered skeleton of a 3-year-old A. afarensis girl comprises almost the entire skull and torso, and most parts of the limbs. The features of the skeleton suggest adaptation to walking upright (bipedalism) as well as tree-climbing, features that match the skeletal features of Lucy and fall midway between human and humanoid ape anatomy. "Baby Lucy" has officially been named "Selam" (meaning peace in most Ethiopian languages). [1]

Others

Related work

Further findings at Afar, including the many hominin bones in site 333, produced more bones of concurrent date, and led to Johanson and White's eventual argument that the Koobi Fora hominins were concurrent with the Afar hominins. In other words, Lucy was not unique in evolving bipedalism and a flat face.

Recently, an entirely new species has been discovered, called Kenyanthropus platyops, however the cranium KNM WT 40000 has a much distorted matrix making it hard to distinguish (however a flat face is present). This had many of the same characteristics as Lucy, but is possibly an entirely different genus.

Another species, called Ardipithecus ramidus, was found by White and colleagues in the 1990s. This was fully bipedal, yet appears to have been contemporaneous with a woodland environment, and, more importantly, contemporaneous with Australopithecus afarensis. Scientists have not yet been able to draw an estimation of the cranial capacity of Ar. ramidus as only small jaw and leg fragments have been discovered thus far.

參考

- ^ Johanson 1981,第283-297頁

- ^ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Jones, S. Martin; & R. Pilbeam (ed.) (2004). The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Human Evolution (8th ed.).Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-46786-1

- ^ BBC - Science & Nature - The evolution of man. Mother of man - 3.2 million years ago. [2007-11-01].

- ^ PREMOG - Research. How Lucy walked. Primate Evolution & Morphology Group (PREMOG), the Department of Human Anatomy and Cell Biology, the School of Biomedical Sciences at the University of Liverpool. 18 May 2007 [2007-11-01].

- ^ PREMOG - Supplementry Info. The Laetoli Footprint Trail: 3D reconstruction from texture; archiving, and reverse engineering of early hominin gait. Primate Evolution & Morphology Group (PREMOG), the Department of Human Anatomy and Cell Biology, the School of Biomedical Sciences at the University of Liverpool. 18 May 2007 [2007-11-01].

- ^ Ian Sample, science correspondent. New theory rejects popular view of man's evolution - Research - EducationGuardian.co.uk. June 1, 2007 [2007-11-05].

- ^ BBC NEWS - Science/Nature - Upright walking 'began in trees'. 31 May 2007 [2007-11-05].

- ^ Thorpe S.K.S.; Holder R.L., and Crompton R.H. PREMOG - Supplementry Info. Origin of Human Bipedalism As an Adaptation for Locomotion on Flexible Branches. Primate Evolution & Morphology Group (PREMOG), the Department of Human Anatomy and Cell Biology, the School of Biomedical Sciences at the University of Liverpool. 24 May 2007 [2007-11-01].

- ^ Aaron G. Filler. Redefining the word “Human” – Do Some Apes Have Human Ancestors? : OUPblog. December 24, 2007 [2007-12-27].

- ^ Aaron G. Filler. PLoS ONE: Homeotic Evolution in the Mammalia: Diversification of Therian Axial Seriation and the Morphogenetic Basis of Human Origins. October 10, 2007 [2007-12-27].

- ^ Johanson 1981,第265-266, 278-279, 283-297頁

- ^ Yoel Rak; Avishag Ginzburg and Eli Geffen. From the Cover: Gorilla-like anatomy on Australopithecus afarensis mandibles suggests Au. afarensis link to robust australopiths -- Rak et al. 104 (16): 6568 -- Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. April 17, 2007 [2007-10-19].

- ^ Yoel Rak; Avishag Ginzburg and Eli Geffen. From the Cover: Gorilla-like anatomy on Australopithecus afarensis mandibles suggests Au. afarensis link to robust australopiths -- Rak et al. 104 (16): 6568 Data Supplement - HTML Page - index.htslp -- Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. April 17, 2007 [2007-10-19].

- BBC - Dawn of Man (2000) by Robin Mckie| ISBN 0-7894-6262-1

- Barraclough, G. Stone, N. (ed.) , 编. Atlas of World History 3rd edition. Times Books Limited. 1989. ISBN 0-7230-0304-1.

- Australopithecus afarensis from The Human Origins Program at the Smithsonian Institution

- Delson, E., I. Tattersall, J.A. Van Couvering & A.S. Brooks (eds.) (编). Encyclopedia of human evolution and prehistory 2nd Edition. Garland Publishing, New York. 2000. ISBN 0-8153-1696-8.

- Johanson, Donald; Edey, Lucy, the Beginnings of Humankind, Granada, 1981, ISBN 0-586-08437-1

外部連結

- Asa Issie, Aramis and the origin of Australopithecus

- Lucy at the American Museum of Natural History in Manhattan

- Lucy at the Institute of Human Origins at Arizona State University

- Asfarensis

- Anthropological skulls and reconstructions

- Becoming Human: Paleoanthropology, Evolution and Human Origins

- National Geographic "Dikika baby"

- MNSU

- Archaeology Info

- Smithsonian