猫传染性腹膜炎:修订间差异

维护清理 |

→诊断: 内容扩充 |

||

| 第34行: | 第34行: | ||

==诊断== |

==诊断== |

||

目前尚不存在针对性 |

除了送往实验室进行[[逆转录PCR]]外,目前尚不存在广泛推行的FIP针对性确诊手段,只能根据检测结果进行推断,这导致FIP存在一定的误诊率。 |

||

===湿性FIP=== |

===湿性FIP=== |

||

一般来说,患猫需在动物医院进行一系列的检查,并综合考量所有的检查结果,来确诊或排除所患为FIP<ref name="FIP"/><ref>{{cite journal|last1=Jeffery|first1=Unity|last2=Deitz|first2=Krysta|last3=Hostetter|first3=Shannon|title=Positive predictive value of albumin: globulin ratio for feline infectious peritonitis in a mid-western referral hospital population|journal=Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery|date=2012-07-18|volume=14|issue=12|pages=903–905|doi=10.1177/1098612X12454862}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|title=Addie:Diagnosis of FIP|url=http://www.catvirus.com/WhatIsFIP.htm#Diagnosis%20of%20FIP|website=CatVirus|accessdate=2018-04-27}}</ref>。 |

|||

#检测积液的蛋白质浓度。若浓度低于35g/L,则基本可以排除是FIP的可能性。 |

|||

#检测积液中淋巴细胞的占比。若淋巴细胞比例很高,则可以排除FIP可能性。 |

|||

#检测积液中的巨噬细胞类型。如果免疫染色法({{lang-en|Immunostaining}})的检查结果表明积液中的巨噬细胞是对抗冠状病毒的类型,则FIP可能性高,但反之无法排除可能性。 |

|||

#检测积液成分。湿性FIP的积液中含有大量的球蛋白和炎性细胞(中性粒细胞、巨噬细胞、淋巴细胞),若符合,则FIP的可能性高。需要注意的是,近年研究表明传统的{{link-en|李凡他测试|Rivalta test}}并不可靠。 |

|||

#检测积液的白球比,即白蛋白与球蛋白的比例,又称A/G比({{lang-en|albumin to globulin ratio}})。FIP患猫的白蛋白减少而球蛋白超标,具体而言,若白球比高于0.8,则可以排除FIP可能性;若白球比低于0.4,则有可能是FIP,但此方法可靠性不高。 |

|||

#检测积液中的冠状病毒抗体的效价({{lang-en|antibody titer}})。如果患猫在表现出明显的FIP症状的同时抗体效价很高,则有可能是传腹,但此方法可靠性不高。 |

|||

将积液样本送往专门的实验室,运用逆转录PCR技术检测积液中是否存在病毒的[[RNA]],是诊断湿性FIP的最直接的方法<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Felten|first1=Sandra|last2=Leutenegger|first2=Christian M.|last3=Balzer|first3=Hans-Joerg|last4=Pantchev|first4=Nikola|last5=Matiasek|first5=Kaspar|last6=Wess|first6=Gerhard|last7=Egberink|first7=Herman|last8=Hartmann|first8=Katrin|title=Sensitivity and specificity of a real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction detecting feline coronavirus mutations in effusion and serum/plasma of cats to diagnose feline infectious peritonitis|journal=BMC Veterinary Research|date=2017-08-02|volume=13|issue=1|doi=10.1186/s12917-017-1147-8}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last1=Doenges|first1=SJ|last2=Weber|first2=K|last3=Dorsch|first3=R|last4=Fux|first4=R|last5=Hartmann|first5=K|title=Comparison of real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction of peripheral blood mononuclear cells, serum and cell-free body cavity effusion for the diagnosis of feline infectious peritonitis.|journal=Journal of feline medicine and surgery|date=2017-04|volume=19|issue=4|pages=344-350|doi=10.1177/1098612X15625354|pmid=26787293}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last1=Longstaff|first1=Louise|last2=Porter|first2=Emily|last3=Crossley|first3=Victoria J|last4=Hayhow|first4=Sophie E|last5=Helps|first5=Christopher R|last6=Tasker|first6=Séverine|title=Feline coronavirus quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction on effusion samples in cats with and without feline infectious peritonitis|journal=Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery|date=2016-07-10|volume=19|issue=2|pages=240–245|doi=10.1177/1098612X15606957}}</ref>。 |

|||

===干性FIP=== |

===干性FIP=== |

||

==参考来源== |

==参考来源== |

||

{{reflist|30em}} |

{{reflist|30em}} |

||

2018年4月27日 (五) 13:08的版本

| 本条目近期正在擴充或大幅編修。 若本条目已數日無大修改,請移除本模板。 致添加本模板的編者:如須在短時間內大幅修改,請務必在編輯期間用 {{inuse}}或{{inuse2}}來取代本模板。本条目由Hal 0005(贡献·日志)於6年前最后编辑。 |

猫传染性腹膜炎(英語:Feline Infectious Peritonitis,FIP)是一种发生于猫的致命的异常免疫反应,由猫携带的猫冠状病毒(英語:Feline Coronavirus,FCoV)发生变异而引起,目前仍为绝症。

病症发现

作为症状通常极为明显的一种致命疾病,FIP在第二次世界大战前却没有得到任何记载,动物医学界认为这是由于FIP在战后方才出现[1]。1963年,兽医Jean Holtzworth根据她在波士顿天使纪念医院的诊断经历首次描述了这种疾病。1973年,约翰霍普金斯大学的两位病理学家John Strandberg和Richard Montali首次研究了FIP在微观层面的发病情况。截至2011年,FIP已位列发达国家宠物猫致死性传染病的第一名[2]。学界认为,发病率的攀升与战后饲养宠物方式改变,猫从田野、乡村搬入了公寓、别墅,同时宠物商店、猫舍与动物收容所等拥挤的运转枢纽纷纷建立,导致猫有更大几率互相传染猫冠状病毒有关;另外,防治猫白血病、猫瘟等以往猫的主要疾病的疫苗得以研发和推行,人类却仍对FIP束手无策,这也导致了其排名的飙升[1]。

2012年,Niels Pedersen通过DNA测序确认了FIP由突变的猫冠状病毒导致[3],而2013年康奈尔大学兽医学院的一项实验再度证实了这一发现[4]。

病因

FIP因猫感染猫冠状病毒,而后猫冠状病毒发生变异而引起[5]。猫冠状病毒是一种胃肠道病毒,通常不会感染至其他系统,此时无症状或最多造成温和的腹泻或上呼吸道感染,如打喷嚏,流眼泪等[6],猫龄五到七周时尤甚,因母源抗体含量会在这个时期降低[7]。

任何携带猫冠状病毒的猫都有发展为腹膜炎的潜在危险,但只有少于10%的猫会因猫冠状病毒变异而患上FIP[6]。病毒变异后会传播至除肠上皮细胞、肺部、血液以外的身体其他部位,渐进性地引起全身炎症反应,尤其是在腹部[8]。截至2018年,动物医学界仍未能就猫冠状病毒会在什么因素影响下突变为腹膜炎病毒、其中病毒本身因素与猫的身体因素的影响分占几何等问题得出明确结论[9]。

传染

猫冠状病毒具有传染性,但变异为腹膜炎病毒后会失去在猫间传染的能力,因此FIP本身并没有传染性。猫冠状病毒通过粪便传播,因此共用猫砂、猫砂铲等行为都可能导致感染[10]。如果一群群居的猫同时确诊FIP,这并非是它们互相传染了FIP,而仅仅是它们互相传染猫冠状病毒后,恰好同时变异发病,其体内的腹膜炎病毒是各自独立变异出来的,结构上存在区别[11]。

猫的密度越高,感染猫冠状病毒的猫的比例越高。在猫舍、动物收容所等猫高密度群居的室内场所,猫冠状病毒的感染非常常见,许多家猫便是在此期间感染了病毒。澳大利亚的一项研究表明,澳大利亚34%的家猫呈猫冠状病毒阳性[12];瑞典的一项研究发现,瑞典17%的家猫接触过猫冠状病毒[13]。而野生猫、流浪猫感染猫冠状病毒的比例则大幅低于家猫,其种群密度越接近自然状态,病毒感染率越低[14]。

临床症状

FIP的早期患猫会表现出消沉、厌食、发热、体重下降、腹泻、皮毛杂乱无光等症状,但由于这些症状较为常见,许多猫病都会导致上述的异常表现,因此通常需要进一步检查和持续观察才能诊断为FIP。

根据后期临床症状不同,主要分为两种FIP:渗出性(英語:effusive),即湿性(英語:wet)FIP,以及非渗出性(英語:non-effusive),即干性(英語:dry)FIP,但亦有少数FIP患猫同时表现两类症状。

湿性FIP

湿性FIP较为常见,约占全部病例的60%至70%,且病情发展较快[15]。湿性FIP的特征为纤维素性胸膜炎和腹膜炎,同时伴有明显的胸腔、腹腔积液,严重时甚至危及呼吸。湿性FIP积液外观粘稠、泛黄,混杂着蛋白质、白细胞、血浆。但积液并非病毒腹膜炎病毒的产物,而是体液免疫系统过度反应的表现;呈现湿性FIP主要是由于患猫的细胞媒介性免疫反应较弱,体液性免疫反应较强[16]。

然而,心血管疾病、乳糜胸、肝病、肾病、肿瘤,低蛋白症、泌尿道受损以及其它原因导致的腹膜炎同样会导致胸腹腔产生积液,因此仅凭积液现象无法诊断FIP[1]。

干性FIP

干性FIP的实质则是非防御性细胞免疫反应所引发的炎症反应[16]。免疫系统为了将身体组织中已被腹膜炎病毒入侵的部分隔绝开来,产生肉芽组织对这些部分进行包裹、阻隔。由于腹膜炎病毒可能入侵眼睛、肝脏、肾脏、淋巴结、神经系统等种种组织器官及系统,加之免疫系统作出的过激反应,患猫可能会出现多种症状。一般来说,干性FIP患猫的眼部和神经系统较容易表现出异常症状,若眼部出现炎症的同时神经系统同样出现如行走不稳、萎靡不振、抽搐癫痫等症状,那么该猫所患很有可能是FIP[17]。

同样,干性FIP也存在症状类似的疾病:肝门静脉分流(英語:Liver Shunts),患猫可能发生间歇性的抽搐。在此情况下,应进行胆汁酸测定以进行鉴别[1]。

诊断

除了送往实验室进行逆转录PCR外,目前尚不存在广泛推行的FIP针对性确诊手段,只能根据检测结果进行推断,这导致FIP存在一定的误诊率。

湿性FIP

一般来说,患猫需在动物医院进行一系列的检查,并综合考量所有的检查结果,来确诊或排除所患为FIP[1][18][19]。

- 检测积液的蛋白质浓度。若浓度低于35g/L,则基本可以排除是FIP的可能性。

- 检测积液中淋巴细胞的占比。若淋巴细胞比例很高,则可以排除FIP可能性。

- 检测积液中的巨噬细胞类型。如果免疫染色法(英語:Immunostaining)的检查结果表明积液中的巨噬细胞是对抗冠状病毒的类型,则FIP可能性高,但反之无法排除可能性。

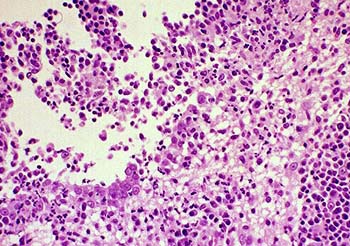

- 检测积液成分。湿性FIP的积液中含有大量的球蛋白和炎性细胞(中性粒细胞、巨噬细胞、淋巴细胞),若符合,则FIP的可能性高。需要注意的是,近年研究表明传统的李凡他测试并不可靠。

- 检测积液的白球比,即白蛋白与球蛋白的比例,又称A/G比(英語:albumin to globulin ratio)。FIP患猫的白蛋白减少而球蛋白超标,具体而言,若白球比高于0.8,则可以排除FIP可能性;若白球比低于0.4,则有可能是FIP,但此方法可靠性不高。

- 检测积液中的冠状病毒抗体的效价(英語:antibody titer)。如果患猫在表现出明显的FIP症状的同时抗体效价很高,则有可能是传腹,但此方法可靠性不高。

将积液样本送往专门的实验室,运用逆转录PCR技术检测积液中是否存在病毒的RNA,是诊断湿性FIP的最直接的方法[20][21][22]。

干性FIP

参考来源

- ^ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Ron Hines. Feline Infectious Peritonitis (FIP) And Your Cat. 2nd Chance. [2018-04-27].

- ^ Vogel, Liesbeth; Van der Lubben, Mariken; Te Lintelo, Eddie G.; Bekker, Cornelis P.J.; Geerts, Tamara; Schuijff, Leontine S.; Grinwis, Guy C.M.; Egberink, Herman F.; Rottier, Peter J.M. Pathogenic characteristics of persistent feline enteric coronavirus infection in cats. Veterinary Research. 2010-07-23, 41 (5): 71. doi:10.1051/vetres/2010043.

- ^ Chang HW; Egberink HF; Rebecca H; Spiro DJ; Rottier PJM. Spike Protein Fusion Peptide and Feline Coronavirus Virulence. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2012, 18 (7): 1089-1095.

- ^ Licitra, Beth N.; Millet, Jean K.; Regan, Andrew D.; Hamilton, Brian S.; Rinaldi, Vera D.; Duhamel, Gerald E.; Whittaker, Gary R. Mutation in Spike Protein Cleavage Site and Pathogenesis of Feline Coronavirus. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2013-07, 19 (7): 1066–1073. doi:10.3201/eid1907.121094.

- ^ Addie D; Belák S; Boucraut-Baralon C. Feline infectious peritonitis. ABCD guidelines on prevention and management. Journal of Feline Medicine & Surgery. 2009, 11 (7): 594-604.

- ^ 6.0 6.1 貓感染性腹膜炎. Hongkong Vet. [2018-04-27].

- ^ Porter E; Tasker S; Day MJ; Harly R; Kipar A; Siddell SG; Helps CR. Amino acid changes in the spike protein of feline coronavirus correlate with systemic spread of virus from the intestine and not with feline infectious peritonitis. Veterinary Research. 2014-04-05, 45 (1): 49-49.

- ^ Pedersen NC; Eckstrand C; Liu H; Leutenegger C; Murphy B. Levels of feline infectious peritonitis virus in blood, effusions, and various tissues and the role of lymphopenia in disease outcome following experimental infection. Veterinary Microbiology. 2015, 175 (2-4): 157-166.

- ^ Pederson NC. An update on feline infectious peritonitis: virology and immunopathogenesis. Veterinary Journal. 2014, 201 (2): 123-132.

- ^ How cats become infected with feline coronavirus: animation. [2018-04-27].

- ^ Chang HW; Groot RJD; Egberink HF; Rottier PJM. Feline infectious peritonitis: insights into feline coronavirus pathobiogenesis and epidemiology based on genetic analysis of the viral 3c gene. Journal of General Virology. 2010, 91 (2): 415.

- ^ Bell ET; Toribio JA; White JD; Malik R; Norris JM. Seroprevalence study of feline coronavirus in owned and feral cats in Sydney, Australia. Australian Veterinary Journal. 2010, 84 (3): 74–81.

- ^ Holst BS; Englund L; Palacios S; Renström L; Berndtsson LT. Prevalence of antibodies against feline coronavirus and Chlamydophila felis in Swedish cats.. Journal of Feline Medicine & Surgery. 2006, 8 (3): 207-211.

- ^ Leutenegger CM; Hofmannlehmann R; Riols C; Liberek M; Worel G; Lups P; Fehr D; Hartmann M; Weilenmann P; Lutz H. VIRAL INFECTIONS IN FREE-LIVING POPULATIONS OF THE EUROPEAN WILDCAT. Journal of Wildlife Diseases. 1999, 35 (4): 678-86.

- ^ Hoskins JD. Coronavirus infection in cats. Veterinary Clinics of North America Small Animal Practice. 1993, 23 (1): 1-16.

- ^ 16.0 16.1 Evermann JF; Henry CJ; Marks SL. Feline infectious peritonitis. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 1995, 206 (8): 1130-4. doi:10.1036/1097-8542.757283.

- ^ Olsen CW. A review of feline infectious peritonitis virus: molecular biology, immunopathogenesis, clinical aspects, and vaccination. Veterinary Microbiology. 1993, 36 (1-2): 1-37.

- ^ Jeffery, Unity; Deitz, Krysta; Hostetter, Shannon. Positive predictive value of albumin: globulin ratio for feline infectious peritonitis in a mid-western referral hospital population. Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery. 2012-07-18, 14 (12): 903–905. doi:10.1177/1098612X12454862.

- ^ Addie:Diagnosis of FIP. CatVirus. [2018-04-27].

- ^ Felten, Sandra; Leutenegger, Christian M.; Balzer, Hans-Joerg; Pantchev, Nikola; Matiasek, Kaspar; Wess, Gerhard; Egberink, Herman; Hartmann, Katrin. Sensitivity and specificity of a real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction detecting feline coronavirus mutations in effusion and serum/plasma of cats to diagnose feline infectious peritonitis. BMC Veterinary Research. 2017-08-02, 13 (1). doi:10.1186/s12917-017-1147-8.

- ^ Doenges, SJ; Weber, K; Dorsch, R; Fux, R; Hartmann, K. Comparison of real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction of peripheral blood mononuclear cells, serum and cell-free body cavity effusion for the diagnosis of feline infectious peritonitis.. Journal of feline medicine and surgery. 2017-04, 19 (4): 344–350. PMID 26787293. doi:10.1177/1098612X15625354.

- ^ Longstaff, Louise; Porter, Emily; Crossley, Victoria J; Hayhow, Sophie E; Helps, Christopher R; Tasker, Séverine. Feline coronavirus quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction on effusion samples in cats with and without feline infectious peritonitis. Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery. 2016-07-10, 19 (2): 240–245. doi:10.1177/1098612X15606957.