海蟾蜍:修订间差异

←建立内容为“{{translating|time=2009-11-10}} {{Taxobox | name = 海蟾蜍 | status = LC | status_system = IUCN3.1 | trend = up | status_ref = <ref name="iucn">{{IUC...”的新頁面 |

(没有差异)

|

2009年11月10日 (二) 08:21的版本

| 此條目目前正依照其他维基百科上的内容进行翻译。 (2009年11月10日) |

| 海蟾蜍 | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||

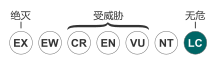

| 保护状况 | ||||||||||||||

| 科學分類 | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| 二名法 | ||||||||||||||

| Bufo marinus (Linnaeus, 1758) | ||||||||||||||

海蟾蜍的分佈地:

藍色的是原產地;紅色的是引入地。 | ||||||||||||||

| 異名 | ||||||||||||||

|

海蟾蜍(學名Bufo marinus),又名美洲巨蟾蜍、甘蔗蟾蜍、蔗蟾蜍或蔗蟾,是原產於中美洲及南美洲一種陸生的蟾蜍。牠們的繁殖能力很強,一次就可以產達幾千顆卵。成體長10-15厘米;紀錄最大的標本重達2.65公斤及長38厘米。

海蟾蜍有毒腺,蝌蚪對於大部份動物也是有具有劇毒的。牠們被引入到多個國家來控制害蟲,不過反而成為了害蟲及入侵物種。

分類

海蟾蜍原先是用來清除甘蔗上的害蟲,故又名甘蔗蟾蜍、蔗蟾蜍或蔗蟾。牠們又名美洲巨蟾蜍,因牠們的體型很大。海蟾蜍則是來自其學名。牠們是由卡爾·林奈所描述。[2]林奈選用此種小名的原因,是因當時艾爾伯特·瑟巴(Albertus Seba)誤將海蟾蜍描繪為陸生及水生的。[3]

在澳洲,海蟾蜍很像當地的Limnodynastes、圓蛙屬及Mixophyes。分別在於海蟾蜍的眼後有很大的腮腺,鼻孔與眼睛之間沒有起脊。[4]牠們與澳洲澤穴蟾很相似,兩者的體型都很大及外表凹凸,但海蟾蜍的虹膜是直縫及呈銀灰色的。[5]幼體的海蟾蜍與耳腺蟾屬的也很像,但成體大腿的顏色卻明顯不同。[6]

於美國,海蟾蜍與其他蟾蜍屬很相似。很易將牠們與虎斑蟾蜍混淆,唯一不同的是腮腺前有兩個球。[7]

特徵

The cane toad is very large;[8] the females are significantly longer than males,[9] reaching an average length of 10–15 cm (4–6 in).[8] "Prinsen", a toad kept as a pet in Sweden, is listed by the Guinness Book of Records as the largest recorded specimen. It reportedly weighed 2.65 kilograms (5.84 lb) and measured 38 cm (15 in) from snout to vent, or 54 cm (21 in) when fully extended.[10] Larger toads tend to be found in areas of lower population density.[11] They have a life expectancy of 10 to 15 years in the wild,[12] and can live considerably longer in captivity, with one specimen reportedly surviving for 35 years.[13]

The skin of the cane toad is dry and warty.[8] It has distinct ridges above the eyes, which run down the snout.[14] Individual cane toads can be grey, yellowish, red-brown or olive-brown, with varying patterns.[15] A large parotoid gland lies behind each eye.[8] The ventral surface is cream-coloured and may have blotches in shades of black or brown. The pupils are horizontal and the irises golden.[5] The toes have a fleshy webbing at their base,[8] and the fingers are free of webbing.[15]

The juvenile cane toad is much smaller than the adult cane toad at 5–10 cm (2–4 in) long. Typically, they have smooth, dark skin, although some specimens have a red wash. Juveniles lack the adults' large parotoid glands, so they are usually less poisonous.[11] The tadpoles are small and uniformly black, and are bottom-dwellers, tending to form schools.[16] Tadpoles range from 10 to 25 mm (0.4–1.0 in) in length.[17]

生態及行為

The common name "Marine Toad" and the scientific name Bufo marinus suggest a link to marine life,[18] but the adult cane toad is entirely terrestrial, only venturing to fresh water to breed. Tadpoles have been found to tolerate salt concentrations equivalent to at most 15% that of sea water.[19] The cane toad inhabits open grassland and woodland, and has displayed a "distinct preference" for areas that have been modified by humans, such as gardens and drainage ditches.[20] In their native habitats, the toads can be found in subtropical forests,[17] although dense foliage tends to limit their dispersal.[21]

The cane toad begins life as an egg, which is laid as part of long strings of jelly in water. A female lays 8,000–25,000 eggs at once and the strings can stretch up to 20 metres (65 ft) in length.[18] The black eggs are covered by a membrane and their diameter is approximately 1.7–2.0 mm (0.07–0.08 in).[18] The rate at which an egg evolves into a tadpole is dependent on the temperature: the pace of development increases with temperature. Tadpoles typically hatch within 48 hours, but the period can vary from 14 hours up to almost a week.[18] This process usually involves thousands of tadpoles—which are small, black and have short tails—forming into groups. It takes between 12 and 60 days for the tadpoles to develop into toadlets, with four weeks being typical.[18] Similarly to their adult counterparts, eggs and tadpoles are toxic to many animals.[8]

When they emerge, toadlets typically are about 10–11 mm (0.39–0.43 in) in length, and grow rapidly. While the rate of growth varies by region, time of year and gender, Zug and Zug found an average initial growth rate of 0.647 mm (0.025 in) per day, followed by an average rate of 0.373 mm (0.015 in) per day. Growth typically slows once the toads reach sexual maturity.[22] This rapid growth is important for their survival—in the period between metamorphosis and sub–adulthood, the young toads lose the toxicity that protected them as eggs and tadpoles, but have yet to fully develop the parotoid glands that produce bufotoxin.[23] Because they lack this key defence, it is estimated that only 0.5% of cane toads reach adulthood.[11][24]

As with rates of growth, the point at which the toads become sexually mature varies across different regions. In New Guinea, sexual maturity is reached by female toads with a snout–vent length of between 70 and 80 mm (2.76–3.15 in), while toads in Panama achieve maturity when they are between 90 and 100 mm (3.54–3.94 in) in length.[25] In tropical regions, such as their native habitats, breeding occurs throughout the year, but in subtropical areas, breeding occurs only during warmer periods that coincide with the onset of the wet season.[26]

The cane toad is estimated to have a critical thermal maximum of 40–42 °C (104–107.6 °F) and a minimum of around 10–15 °C (50–59 °F).[27] The ranges can change due to adaptation to the local environment.[28] The cane toad has a high tolerance to water loss—one study showed that some can withstand a 52.6% loss of body water, allowing them to survive outside tropical environments.[28]

食性

Most frogs identify prey by movement, and vision appears to be the primary method by which the cane toad detects prey; however, the cane toad can also locate food using its sense of smell.[29] They eat a wide range of material; in addition to the normal prey of small rodents, reptiles, other amphibians, birds and a range of invertebrates, they also eat plants, dog food and household refuse. Cane toads have a habit of swallowing their prey.[30]

防衛

The adult cane toad has enlarged parotoid glands behind the eyes, and other glands across their back. When the toads are threatened, their glands secrete a milky-white fluid known as bufotoxin.[31] Components of bufotoxin are toxic to many animals;[32] there have even been human deaths due to the consumption of cane toads.[17]

Bufotenin, one of the chemicals excreted by the cane toad, is classified as a Class 1 drug under Australian law, alongside heroin and marijuana. It is thought that the effects of bufotenin are similar to that of mild poisoning; the stimulation, which includes mild hallucinations, lasts for less than an hour.[33] As the cane toad excretes bufotenin in small amounts, and other toxins in relatively large quantities, toad licking could result in serious illness or death.[34]

In addition to releasing toxin, the cane toad is capable of inflating its lungs, puffing up and lifting its body off the ground to appear taller and larger to a potential predator.[31]

掠食者

Many species prey on the cane toad in its native habitat. These include the Broad-snouted Caiman (Caiman latirostris), the Banded Cat-eyed Snake (Leptodeira annulata), the eel (family: Anguillidae), various species of killifish,[35] the Rock flagtail (Kuhlia rupestris), some species of catfish (order: Siluriformes) and some species of ibis (subfamily: Threskiornithinae).[35] Predators outside the cane toad's native range include the Whistling Kite (Haliastur sphenurus), the Rakali (Hydromys chrysogaster), the Black Rat (Rattus rattus) and the Water Monitor (Varanus salvator). There have been occasional reports of the Tawny Frogmouth (Podargus strigoides) and the Papuan Frogmouth (Podargus papuensis)[36] feeding on cane toads.

Distribution

The cane toad is native to the Americas, and its range stretches from the Rio Grande Valley in southern Texas to the central Amazon and south-eastern Peru.[37][38] This area encompasses both tropical and semi-arid environments. The density of the cane toad is significantly lower within its native distribution than in places where it has been introduced. In South America, the density was recorded to be 20 adults per 100 metres (109 yards) of shoreline, 50–100 times lower than the density in Australia.[39]

Introductions

The cane toad has been introduced to many regions of the world—particularly the Pacific—for the biological control of agricultural pests.[37] These introductions have generally been well-documented, and the cane toad may be one of the most studied of any introduced species.[40]

Before the early 1840s, the cane toad had been introduced into Martinique and Barbados, from French Guiana and Guyana.[41] An introduction to Jamaica was made in 1844 in an attempt to reduce the rat population.[42] Despite its failure to control the rodents, the cane toad was introduced to Puerto Rico in the early 20th century in the hope that it would counter a beetle infestation that was ravaging the sugar cane plantations. The Puerto Rican scheme was successful and halted the economic damage caused by the beetles, prompting scientists in the 1930s to promote it as an ideal solution to agricultural pests.[43]

As a result, many countries in the Pacific region emulated the lead of Puerto Rico and introduced the toad in the 1930s.[44] There are introduced populations in Australia, Florida,[45] Papua New Guinea,[46] the Philippines,[47] the Ogasawara and Ryukyu Islands of Japan,[48] most Caribbean islands,[44] Fiji and many other Pacific islands.[44] including Hawaii[49][50] Since then, the cane toad has become a pest in many host countries, and poses a serious threat to native animals.[51]

Australia

Following the apparent success of the cane toad in eating the beetles that were threatening the sugar cane plantations of Puerto Rico, and the fruitful introductions into Hawaii and the Philippines, there was a strong push for the cane toad to be released in Australia to negate the pests that were ravaging the Queensland cane fields.[52] As a result, 102 toads were collected from Hawaii, equally comprising males and females, and brought to Australia.[53] After an initial release in August 1935, the Commonwealth Department of Health decided to ban future introductions until a study was conducted into the feeding habits of the toad. The study was completed in 1936 and the ban lifted, at which point large scale releases were undertaken—by March, 1937, 62,000 toadlets had been released into the wild.[52][53] The toads became firmly established in Queensland, increasing exponentially in number and extending their range into the Northern Territory and New South Wales.[15][53]

Tyler argues that the toad was unsuccessful in reducing the targeted beetles, in part because the cane fields provided insufficient shelter for the predators during the day.[54] Since its original introduction, the cane toad has had a particularly marked effect on Australian biodiversity. The population of a number of native predatory reptiles has declined, such as the varanid lizards Varanus mertensi, V. mitchelli and V. panoptes, the land snakes Pseudechis australis and Acanthophis antarcticus, and the crocodile species Crocodylus johnstoni; in contrast, the population of the agamid lizard Amphibolurus gilberti—known to be a prey item of V. ponaptes—has increased.[55]

Caribbean

The cane toad was introduced to various Caribbean islands to counter a number of pests that were infesting local crops.[56] While it was able to establish itself on some islands, such as Barbados and Jamaica, other introductions, such as in Cuba before 1900 and in 1946, and on the islands of Dominica and Grand Cayman, were unsuccessful.[57]

The earliest recorded introductions were to Barbados and Martinique. The Barbados introductions were focused on the biological control of pests that were damaging the sugar cane crops,[58] and while the toads became abundant, they have not been as successful in controlling the pests as in Australia.[59] The toad was introduced to Martinique from French Guiana before 1944 and became established. Today, they reduce the mosquito and mole cricket populations.[60] A third introduction to the region occurred in 1884, when toads appeared in Jamaica, reportedly imported from Barbados to help control the rodent population. While they had no significant effect on the rats, they nevertheless became well established.[61] Other introductions include the release on Antigua—possibly before 1916, although there are suggestions that this initial population may have died out by 1934 and been reintroduced at a later date—[62]and Montserrat, which saw an introduction before 1879 that led to the establishment of a solid population, which was apparently sufficient to survive the Soufrière Hills volcano eruption in 1995.[63]

In 1920, the cane toad was introduced into Puerto Rico to control the populations of white-grub (Phyllophaga spp.), a sugar cane pest.[64] Before this, the pests were manually collected by humans, so the introduction of the toad eliminated labor costs.[64] A second group of toads was imported in 1923, and by 1932 the cane toad was well established.[65] The population of white-grubs dramatically decreased,[64] and this was attributed to the cane toad at the annual meeting of the International Sugar Cane Technologists in Puerto Rico.[51] However, there may have been other factors.[51] The six-year period after 1931—when the cane toad was most prolific, and the white-grub saw dramatic decline—saw the highest ever rainfall for Puerto Rico.[66] Nevertheless, the assumption was that the cane toad controlled the white-grub; this view was reinforced by a Nature article titled "Toads save sugar crop",[51] and this led to large-scale introductions throughout many parts of the Pacific.[67]

More recently, the cane toad has been spotted in Carriacou and Dominica, the latter appearance occurring in spite of the failure of the earlier introductions.[68]

Fiji

The cane toad was introduced into Fiji to combat insects that infested sugar cane plantations. The introduction of the cane toad to the region was first suggested in 1933, following the successes in Puerto Rico and Hawaii. After considering the possible side effects, the national government of Fiji decided to release the toad in 1953, and 67 specimens were subsequently imported from Hawaii.[69] Once the toads were established, a 1963 study concluded that as the toad's diet included both harmful and beneficial invertebrates, it was considered "economically neutral".[50] Today the cane toad can be found on all major islands in Fiji, although they tend to be smaller than their counterparts in other regions.[70]

New Guinea

The cane toad was successfully introduced into New Guinea to control hawk moth larvae that were eating sweet potato crops.[46] The first release occurred in 1937 using toads imported from Hawaii, with a second release the same year using specimens from the Australian mainland. Evidence suggests there was a third release in 1938, consisting of toads that were being used for human pregnancy tests—many species of toad were found to be effective for this task, and were employed for aproximately 20 years after the discovery was announced in 1948.[71][72] Initial reports argued that the toads were effective in reducing the incidence of cutworm and it was suggested that sweet potato yields were improving.[73] As a result, these first releases were followed by further distributions across much of the region,[73] although their effectiveness on other crops, such as cabbages, has been questioned—when the toads were released at Wau, the cabbages provided insufficient shelter and the toads rapidly left the immediate area for the superior shelter offered by the forest.[74] A similar situation had previously arisen in the Australian cane fields, but Tyler suggests this experience was either ignored in New Guinea or was not sufficiently publicized.[74] The cane toad has since become abundant in rural and urban areas.[75]

United States

The cane toad naturally exists in southern Texas, but attempts (both deliberate and accidental) have been made to introduce the species to other parts of the country. These include introductions to the mainland state of Florida and to the islands of Hawaii, as well as largely unsuccessful introductions to Louisiana.[76]

Initial releases into Florida failed. Attempted introductions before 1936 and 1944, made with the objective of controlling sugar cane pests, were unsuccessful as the toads failed to proliferate. Later attempts failed in the same way.[77][78] However, the toad gained a foothold in the state after an accidental release by an importer at Miami International Airport in 1957, and deliberate releases by animal dealers in 1963 and 1964 established the toad in other parts of Florida.[78][79] Today, the cane toad is well established in the state, from the Florida Keys to north of Tampa, and they are gradually extending further northward.[80] While many may regard the toad as a nuisance, in general, their presence does not seem to have adversely affected the native wildlife.[81]

Around 150 cane toads were introduced to Oahu in Hawaii in 1932, and the population swelled to 105,517 after 17 months.[44] The toads were sent to the other islands, and more than 100,000 toads were distributed by July 1934;[82] eventually over 600,000 were transported.[83]

用途

Other than the previously mentioned use as a biological control for pests, the cane toad has been employed in a number of commercial and non-commercial applications. Traditionally, within the toad's natural range in South America, the native population would "milk" the toads for their toxin, which was then employed on hunting arrows. There are also suggestions that the toxins may have been used as a narcotic by the Olmec people. The toad has been hunted as a food source in parts of Peru, and eaten after the removal of the skin and parotoid glands.[84] More recently, the toad's toxins have been used in a number of new ways: bufotenine has been used in Japan as an aphrodisiac and a hair restorer, and in cardiac surgery in China to lower the heart rates of patients.[17]

Other modern applications of the cane toad include pregnancy testing,[84] as pets,[85] laboratory research,[86] and the production of leather goods. Pregnancy testing was conducted in the mid-20th century by injecting urine from a woman into a male toad's lymph sacs, and if spermatozoa appeared in the toad's urine, the patient was deemed to be pregnant.[84] The tests using toads were faster than those employing mammals; toads were easier to raise, and, although the initial 1948 discovery employed Bufo arenarum for the tests, it soon became clear that a variety of anuran species were suitible, including the cane toad. As a result, toads were employed in this task for approximately 20 years.[72] As a laboratory animal, the cane toad is regarded as ideal; they are plentiful, and easy and inexpensive to maintain and handle. The use of the cane toad in experiments started in 1950s, and by the end of 1960s, large numbers were being collected and exported to high schools and universities.[86] Since then, a number of Australian states have introduced or tightened importation regulations.[87] Even dead toads have value. Cane toad skin has been made into leather and novelty items;[88][89] stuffed cane toads, posed and accessorised, have found a home in the tourist market,[90] and attempts have been made to produce fertilizer from their bodies.[91]

參考

- ^ Solís, F., Ibáñez, R., Hammerson, G., Hedges, B., Diesmos, A., Matsui, M., Hero, J.-M., Richards, S., Coloma, L., Ron, S., La Marca, E., Hardy, J., Powell, R., Bolaños, F., Chaves, G. & Ponce, P. Bufo marinus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2008. [2009-11-10].

- ^ Linnaeus, Carolus. Systema naturae per regna tria naturae :secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. 10th edition. Holmiae (Laurentii Salvii). 1758: 824 [2008-09-22] (Latin).

- ^ Beltz, Ellin. Scientific and Common Names of the Reptiles and Amphibians of North America. September 10, 2007 [2009-06-15].

- ^ Vanderduys, Eric; Wilson, Steve. Cane Toads (Fact Sheet) (PDF). Queensland Museum. 2000.

- ^ 5.0 5.1 Giant Burrowing Frog. Wildlife of Sydney. Australian Museum. April 15, 2009 [2009-06-17].

- ^ Barker, John; Grigg, Gordon; Tyler, Michael. A Field Guide to Australian Frogs. Surrey Beatty & Sons. 1995. ISBN 0-949324-61-2.

- ^ Brandt, Laura A.; Mazzotti, Frank J. Marine Toads (Bufo marinus) (PDF). University of Florida. 2005.

- ^ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 Robinson 1998

- ^ Lee 2001,第928頁

- ^ Wyse 1997,第249頁

- ^ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Tyler 1989,第117頁

- ^ Tyler 1989,第117–118頁

- ^ Grenard 2007,第55頁

- ^ 引用错误:没有为名为

VanderduysEric2000p1的参考文献提供内容 - ^ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Cameron 2009

- ^ Tyler 1976,第81頁

- ^ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 Invasive Species Specialist Group 2006

- ^ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 18.4 Tyler 1989,第116頁

- ^ Ely 1944,第256頁

- ^ Lever 2001,第3頁

- ^ Barker, Grigg & Tyler 1995,第380頁

- ^ Zug & Zug 1979,第14–15頁

- ^ Zug & Zug 1979,第15頁

- ^ Anstis 2002,第274頁

- ^ Zug & Zug 1979,第8頁

- ^ Lever 2001,第6頁

- ^ Tyler 1989,第118頁

- ^ 28.0 28.1 Tyler 1989,第119頁

- ^ Lever 2001,第10頁

- ^ Tyler 1989,第130–132頁

- ^ 31.0 31.1 Tyler 1989,第134頁

- ^ Tyler 1989,第134–136頁

- ^ Fawcett 2004,第9頁

- ^ Weil & Davis 1994,第1–8頁

- ^ 35.0 35.1 Tyler 1989,第138–139頁

- ^ Angus 1994,第10–11頁

- ^ 37.0 37.1 Tyler 1989,第111頁

- ^ Zug & Zug 1979,第1–2頁

- ^ Lampo & De Leo 1998,第392頁

- ^ Easteal 1981,第94頁

- ^ Easteal 1981,第96頁

- ^ Lannoo 2005,第417頁

- ^ Tyler 1989,第112–113頁

- ^ 44.0 44.1 44.2 44.3 Tyler 1989,第113–114頁

- ^ Smith 2005,第433–441頁

- ^ 46.0 46.1 Zug, Lindgrem & Pippet 1975,第31–50頁

- ^ Alcala 1957,第90–96頁

- ^ Kidera et al. 2008,第423–440頁

- ^ Oliver & Shaw 1953,第65–95頁

- ^ 50.0 50.1 Hinckley 1963,第253–259頁

- ^ 51.0 51.1 51.2 51.3 Tyler 1989,第113頁

- ^ 52.0 52.1 Tyler 1976,第77頁 引用错误:带有name属性“Tyler1976p77”的

<ref>标签用不同内容定义了多次 - ^ 53.0 53.1 53.2 Easteal 1981,第104頁

- ^ Tyler 1976,第83頁

- ^ Doody et al. 2009,第46–53頁. On snake populations see Shine 2009,第20頁.

- ^ Lever 2001,第67頁

- ^ Lever 2001,第73–74頁

- ^ Lever 2001,第71頁

- ^ Kennedy, Anthony quoted in Lever 2001,第72頁

- ^ Lever 2001,第81頁

- ^ Lever 2001,第78–79頁

- ^ Easteal 1981,第98頁

- ^ Lever 2001,第81–82頁

- ^ 64.0 64.1 64.2 Tyler 1989,第112頁

- ^ Van Volkenberg 1935,第278–279頁. "After a completely successful method of killing white grubs by chemical means was found, the only opportunities for its use in Puerto Rico have been limited to small areas in pineapple plantations at elevations where the toad is even yet not present in sufficient abundance."

- ^ Freeland 1985,第211–215頁

- ^ Tyler 1989,第113–115頁

- ^ Lever 2001,第72–73頁

- ^ Lever 2001,第128–129頁

- ^ Lever 2001,第130–131頁

- ^ Easteal 1981,第103頁

- ^ 72.0 72.1 Tyler, Wassersug & Smith 2007,第6–7頁

- ^ 73.0 73.1 Lever 2001,第118頁

- ^ 74.0 74.1 Tyler 1976,第83–84頁

- ^ Lever 2001,第119頁

- ^ Easteal 1981,第100–102頁

- ^ Lever 2001,第57頁

- ^ 78.0 78.1 Easteal 1981,第100頁

- ^ Lever 2001,第58頁

- ^ Lever 2001,第59頁

- ^ Lever 2001,第61頁

- ^ Lever 2001,第64頁

- ^ Easteal 1981,第101頁

- ^ 84.0 84.1 84.2 Lever 2001,第32頁

- ^ Mattison 1987,第145頁

- ^ 86.0 86.1 Tyler 1976,第85頁

- ^ Tyler 1976,第88–89頁

- ^ McCarin 2008,第8頁

- ^ Hardie 2001,第3頁

- ^ Bateman 2008,第48頁

- ^ Australian Associated Press 2006

References

- Alcala, A. C. Philippine notes on the ecology of the giant marine toad. Silliman Journal. 1957, 4 (2).

- Angus, R. Observation of a Papuan Frogmouth at Cape York [Queensland]. Australian Birds. 1994, 28.

- Anstis, M. Tadpoles of South-Eastern Australia: A Guide with Keys. Reed New Holland. 2002. ISBN 1-876334-63-0.

- Australian Associated Press. Toads to be juiced. Sydney Morning Herald. January 25, 2006 [July 7, 2009].

- Australian State of the Environment Committee. Biodiversity. Australia: CSIRO Publishing. 2002. ISBN 0-643-06749-3.

- Bateman, Daniel. Toad business the stuff of dreams. Townsville Bulletin. May 10, 2008.

- Cameron, Elizabeth. Cane Toad. Wildlife of Sydney. Australian Museum. June 10, 2009 [June 18, 2009].

- Caughley, Graeme; Gunn, Anne. Conservation biology in theory and practice. Wiley-Blackwell. 1996. ISBN 0-865-42431-4.

- Crossland, Michael R.; Alford, Ross A.; Shine, Richard. Impact of the invasive cane toad (Bufo marinus) on an Australian frog (Opisthodon ornatus) depends on minor variation in reproductive timing. Population Ecology. 2009, 158 (4). doi:10.1007/s00442-008-1167-y.

- Doody, J. S.; Green, B.; Rhind, D.; Castellano, C. M.; Sims, R.; Robinson, T. Population-level declines in Australian predators caused by an invasive species. Animal Conservation. 2009, 12 (1).

- Easteal, Simon. The history of introductions of Bufo marinus (Amphibia : Anura); a natural experiment in evolution. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 1981, (16).

- Easteal, Simon; van Beurden, Eric K.; Floyd, Robert B.; Sabath, Michael D. Continuing Geographical Spread of Bufo marinus in Australia: Range Expansion between 1974 and 1980. Journal of Herpetology. June 1985, 19 (2).

- Ely, C. A. Development of Bufo marinus larvae in dilute sea water. Copeia. 1944, 56 (4). doi:1 0.2307/1438692 请检查

|doi=值 (帮助). - Fawcett, Anne. Really caning it. The Sydney Morning Herald. August 4, 2004: 9.

- Freeland, W. J. The Need to Control Cane Toads. Search. 1985,. 16(7–8).

- Grenard, Steve. Frogs and Toads. John Wiley and Sons. 2007. ISBN 0-470-16510-3.

- Hardie, Alan. It's tough selling toads .... Northern Territory News. January 22, 2001.

- Hinckley, A. D. Diet of the giant toad, Budo marinus (L.) in Fiji. Herpetologica. 1963, 18 (4).

- Invasive Species Specialist Group. Ecology of Bufo marinus. Global Invasive Species Database. June 1, 2006 [July 2, 2009].

- Kenny, Julian. The Biological Diversity of Trinidad and Tobago: A Naturalist's Notes. Prospect Press. 2008. ISBN 9-769-50823-3.

- Kidera, N.; Tandavanitj, N.; Oh, D.; Nakanishi, N.; Satoh, A.; Denda, T.; Izawa, M.; Ota, H. Dietary habits of the introduced cane toad Bufo marinus (Amphibia : Bufonidae) on Ishigakijima, southern Ryukyus, Japan. Pacific Science. 2008, 62 (3).

- Lampo, Margarita; De Leo, Giulio A. The Invasion Ecology of the Toad Bufo marinus: from South America to Australia. Ecological Applications. 1998, 8 (2).

- Lannoo, Michael J. Amphibian Declines: The Conservation Status of United States Species. University of California Press. 2005. ISBN 0-520-23592-4.

- Lee, Julian C. Evolution of a Secondary Sexual Dimorphism in the Toad, Bufo marinus. Copeia. 2001, 2001 (4). doi:10.1643/0045-8511(2001)001[0928:EOASSD]2.0.CO;2.

- Lever, Christopher. The Cane Toad. The history and ecology of a successful colonist. Westbury Publishing. 2001. ISBN 1-84103-006-6.

- (拉丁文) Linnaeus, Carolus. Systema naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I. Editio decima, reformata.. Holmiae. (Laurentii Salvii). 1758.

- Mattison, Chris. Frogs & Toads of the World. Blandford Press. 1987. ISBN 0-713-71825-0.

- McCarin, Julie. Kisses for a toad. The Leader. April 29, 2008.

- Oliver, J. A.; Shaw, C. E. The amphibians and reptiles of the Hawaiian Islands. Zoologica (New York). 1953, 38 (5).

- Robinson, Martyn. A field guide to frogs of Australia: from Port Augusta to Fraser Island including Tasmania. Reed New Holland. 1998. ISBN 1-876-33483-3 请检查

|isbn=值 (帮助). - Shine, Rick. Controlling Cane Toads Ecologically (PDF). Australasian Science. July 2009, 30 (6): 20–23.

- Smith, K. G. Effects of nonindigenous tadpoles on native tadpoles in Florida: evidence of competition. Biological Conservation. 2005, 123 (4).

- Solis, Frank; Ibáñez, Roberto; Hammerson, Geoffrey; Hedges, Blair; Diesmos, Arvin; Matsui, Masafumi; Hero, Jean-Marc; Richards, Stephen; Coloma, Luis A.; Ron, Santiago; La Marca, Enrique; Hardy, Jerry; Powell, Robert; Bolaños, Federico; Chaves, Gerardo. Rhinella marina. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2009.1. 2008 [June 15, 2009].

- Tyler, Michael J. Frogs. William Collins (Australia). 1976. ISBN 0-002-11442-9.

- Tyler, Michael J. Australian Frogs. Penguin Books. 1989. ISBN 0-670-90123-7.

- Tyler, Michael J.; Wassersug, Richard; Smith, Benjamin. How frogs and humans interact: Influences beyond habitat destruction, epidemics and global warming. Applied Herpetology. 2007, 4 (1). doi:10.1163/157075407779766741.

- Van Volkenberg, H. L. Biological Control of an Insect Pest by a Toad. Science. 1935, 82 (2125). doi:10.1126/science.82.2125.278.

- Weil, A. T.; Davis, W. Bufo alvarius: a potent hallucinogen of animal origin.. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 1994, 41 (1–2): 1–8. doi:10.1016/0378-8741(94)90051-5.

- Wyse, E. (editor). Guinness Book of Records 1998. Guinness Publishing. 1997. ISBN 0-85112-044-X.

- Zug, G. R.; Lindgrem, E.; Pippet, J. R. Distribution and ecology of marine toad, Bufo marinus, in Papua New Guinea. Pacific Science. 1975, 29 (1).

- Zug, G. R.; Zug, P. B. The Marine Toad, Bufo marinus: A natural history resumé of native populations. Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology. 1979, 284.

外部連結

| 维基共享资源上的多媒体资源 | |

| 维基物种上的物种信息 | |

- Species Profile - Cane Toad (Bufo marinus), National Invasive Species Information Center, National Agricultural Library. Lists general information and resources for cane toad.

Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA