Eyckensis法典

此条目翻译品质不佳。 (2017年3月24日) |

8世纪的《Eyckensis法典》是以2本组成手稿为基础的福音书,据推测这2本手稿形成了12世纪至1988年的卷轴。

《Eyckensis法典》是比利时最古老的书籍[1]。自8世纪起它便一直被保存在当今马泽克(Maaseik) 辖区的领土上,因此得名“Eyckensis”。此书可能创作于埃希特纳赫修道院的书桌上。

手稿A与手稿B的描述

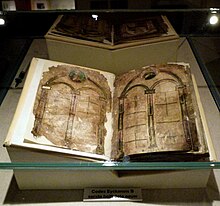

[编辑]Eyckensis法典由133张对开羊皮纸上的两本传道书组成,每张羊皮纸的尺寸为244*183毫米。

第一本手稿(法典A)不完整。它由5张对开纸组成,开头是一全页的传道者肖像(据推测是描画的圣马修),之后是一组不完整的八张教规表。福音传教士的肖像以意大利 - 拜占庭风格呈现,这明显与当前保存在梵蒂冈图书馆的巴贝里尼福音书(Barberini Lat. 570)有关。肖像画的边框是盎格鲁 - 撒克逊结,相当于林迪斯芳福音书的装饰元素。

教规表提供了四本福音书中相应段落的概述。其可作为教规表的目录和索引,以便于查阅文本。手稿A中的教规表装饰有圆柱和拱廊,以及四位福音传教士的符号和圣人的肖像。

第二本手稿(法典B)包含整套的12张教规表和所有4本福音文本。教规表中的装饰有圆柱和拱廊,以及使徒的描述和福音传教士的符号。福音文本是以圆形小写字母写成的,这是7世纪与8世纪时英国与爱尔兰手稿的特点,但也在欧洲大陆使用。每个段落的首个大写字母用红色和黄色圆点勾画。 文本由一个抄写员抄写。

福音文本是拉丁文圣经的一版,大多由圣杰罗姆翻译(圣哲罗姆,公元347年-420年),并有几次添加和变换。福音文本的类似版本可在《凯尔经》(都柏林,三一学院,第58期)、《阿尔马经》(都柏林,三一学院,第52期)和《埃希特纳赫福音》(巴黎国家图书馆,第 Lat.9389期)中找到。

历史(从起源到20世纪)

[编辑]

法典可以追溯到8世纪,最初被保存在原来的Aldeneik本尼迪克特修道院,该修道院于公元728年祝圣。Merovingian贵族德南之王Adelard和妻子Grinuara为他们的女儿Harlindis和Relindis在Meuse河附近的“小而无用的树林”中[2]创建了这所修道院。 修道院因在那里生长的橡树而被命名为Eyke(“橡树”)。 后来,随着邻近的Nieuw-Eyke村(“新橡树” - 当前的Maaseik)的发展,且变得更加重要,原来的村庄的名字变成了Aldeneik(“老橡树”)。 圣威利布罗德将Harlindis祝圣为该宗教区的第一位女修道院院长。 在她死后,圣博尼法斯将她的妹妹Relindis祝圣为她的继任者。

在修道院中使用Eyckensis法典进行研究,并用于传播基督的教导。 据推测现在构成Eyckensis法典的两本福音书是由圣威利布罗德从埃希特纳赫修道院带到了Aldeneik。

两本手稿最有可能在12世纪时整合成了一本书。1571年,Aldeneik修道院被废弃了。从10世纪中叶起,本笃会尼姑被男性教士所取代。伴随着宗教战争日益严重的威胁,教士们在Maaseik的城镇中避难。他们将教堂的珍宝——包括Eyckensis法典——从Aldeneik带到了圣凯瑟琳教堂。

作者身份

[编辑]

几个世纪以来,人们一直相信Eyckensis法典是由Harlindis 和 Relindis著成的,她们是Aldeneik修道院的首位修道院院长,之后被封为圣徒。一位当地的牧师在9世纪时写下了她们的圣徒言行传[3]。文中提到Harlindis和Relindis也写作了传道福音。9世纪时圣徒姐妹的遗物变得越来越重要, Eyckensis法典获得了越来越多的尊重,因其是Harlindis 和Relindis的著作得到了极大的尊重。[2]

然而,第二本手稿的最后几行明确反驳道:Finito volumine deposco ut quicumque ista legerint pro laboratore huius operis depraecentur (在此卷完成之时,我请所有读者为制作此手稿的工人祈祷)。Laborator(“工人”)词性为男性,明确表明手稿的作者为男性。

1994年,由Albert Derolez(根特大学)和Nancy Netzer(波士顿学院)进行的比较分析表明,手稿A和手稿B追溯于同一时期,两者都很可能是在埃希特纳赫修道院创作的,它们甚至可能由同一位抄写员完成[4]。

1957年进行的保护和修复尝试

[编辑]1957年,来自杜塞尔多夫的修复者Karl Sievers试图保护并修复Eyckensis法典。他移除并销毁了18世纪红色天鹅绒封面,之后用Mipofolie层压手稿的所有对开页。Mipofolie是聚氯乙烯(PVC)箔,用邻苯二甲酸二辛酯外部增塑。随着时间的流逝,该箔产生盐酸,侵蚀羊皮纸并且对箔本身具有黄化效应。 羊皮纸的透明度和颜色受到影响,存在于箔中的聚合物可迁移到羊皮纸上并使其变脆。在层压之后,Sievers重新装订了法典。为了能够这样做,他切开了对开页的边缘,这导致彩饰的碎片丢失。

在1987年至1993年间进行的一次新的大规模修复工作中,在化学家Jan Wouters博士的领导下,比利时皇家文化遗产研究所的一个团队精心删除了Mipofolie层压。在去除层压板之后对对开纸的恢复中,开发了创新的羊皮纸片播技术。 为了完成恢复工作,法典的两个组成手稿分别装订[5]。

存档和数字化

[编辑]Eyckensis法典最古老的影像文件起源于约1916年(Bildarchiv Marburg(页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆))。在修复过程时,比利时皇家文化遗产研究所(KIK-IRPA)对手稿进行了拍摄。 1994年出版了一份传真[6]。

2015年,Eyckensis法典在圣凯瑟琳教堂的网站上数字化,由成像实验室和Illuminare——中世纪艺术研究中心|KU Leuven 完成。此项目由Lieve Watteeuw教授[7]领导。与LIBIS(KU Leuven)合作在线获得高分辨率图像。

1986年,Eyckensis法典被认定为不可移动遗产并获得保护。2003年Eyckensis法典被公认为佛兰芒杰作(页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)。

当前研究

[编辑]2016-2017年间,来自Illuminare -中世纪艺术研究中心|KU Leuven(Lieve Watteeuw教授)和比利时皇家文化遗产研究所(Marina Van Bos博士)的团队将再次研究Eyckensis法典。

欲了解更多信息,请查阅:

- www.codexeyckensis.be(页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- Lab-KU Leuven遗产书籍(页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- 比利时皇家文化遗产研究所-(页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)(KIK–IRPA)

参考资料

[编辑]- ^ Coenen, J., Het oudste boek van België, Het Boek 10, 1921, S. 189-194.

- ^ 2.0 2.1 Acta Sanctorium, Martii, unter Leitung von J. Carnandet, 3. Teil, Paris-Rom, 1865, S. 383-390, Abs. 7.

- ^ Abbaye d’Aldeneik, à Maaseik, in Monasticon belge, 6, Province de Limbourg, Lüttich, 1976, S. 87.

- ^ Netzer, N.(1994) Cultural Interplay in the Eighth Century. The Trier Gospels and the Making of a Scriptorium at Echternach, Cambridge-New York.

- ^ Wouters, J., Gancedo, G., Peckstadt, A., Watteeuw, L. (1992). The conservation of the Codex Eyckensis: the evolution of the project and the assessment of materials and adhesives for the repair of parchment. The Paper Conservator 16, 67-77. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/03094227.1992.9638578

- ^ Coppens, C. , A. Derolez und H. Heymans (1994) Codex Eyckensis: an insular gospel book from the abbey of Aldeneik. Maaseik: Museactron.

- ^ https://www.arts.kuleuven.be/english/news/codex eyckensis

外部链接

[编辑]- The Codex Eyckensis on www.codexeyckensis.be(页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- The Codex Eyckensis, online high-resolution images on LIBIS(页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- The Codex Eyckensis on Erfgoedplus(页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- The Codex Eyckensis on www.museamaaseik.be(页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- The Codex Eyckensis on Europeana

- The Codex Eyckensis in the early 20th century in the Marburg Bildarchiv(页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆), Deutsches Dokumentationszentrum für Kunstgeschichte

- The Codex Eyckensis before and after the restoration in the late 20th century, on the Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage website(页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

Bibliography

[编辑]Coenen, J. (1921) Het oudste boek van België, Het Boek 10, pp. 189-194.

Coppens, C., A. Derolez en H. Heymans (1994) Codex Eyckensis: an insular gospel book from the abbey of Aldeneik, Antwerpen/Maaseik, facsimile.

De Bruyne, D. (1908) L'évangéliaire du 8e siècle, conservé à Maeseyck, Bulletin de la Société d'Art et d'Histoire du Diocèse de Liège 17, pp. 385-392.

Dierkens, A. (1979) Evangéliaires et tissus de l’abbaye d’Aldeneik. Aspect historiographique, Miscellanea codicologica F. Masai Dicata (Les publications de Scriptorium 8), Gent, pp. 31-40.

Falmagne, T. (2009) Die Echternacher Handschriften bis zum Jahr 1628 in den Beständen der Bibliothèque nationale de Luxembourg sowie Archives diocésaines de Luxembourg, der Archives nationale, der Section historique de l' Institut grand-ducal und des Grand Séminaire de Luxembourg, Wiesbaden, Harrassowitz Verlag, 2 Banden: 311pp. + [64] ill., 792pp.

Gielen J. (1880) Le plus vieux manuscrit Belge, Journal des Beaux-Arts et de la Littérature 22, nr. 15, pp. 114-115.

Gielen, J. (1891) Evangélaire d'Eyck du VIIIe siècle, Bulletin Koninklijke Commissie voor Kunst en Oudheden 30, pp. 19-28.

Hendrickx, M. en W. Sangers (1963) De kerkschat der Sint-Catharinakerk te Maaseik. Beschrijvende Inventaris, Limburgs Kunstpatrimonium I, Averbode, pp. 33-35.

Mersch, B. (1982) Het evangeliarium van Aldeneik, Maaslandse Sprokkelingen 6, pp. 55-79.

Netzer, N. (1994) Cultural Interplay in the 8th century and the making of a scriptorium, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 258pp.

Nordenfalk, C. (1932) On the age of the earliest Echternach manuscripts, Acta Archeologica, vol. 3, fasc. 1, Kopenhagen: Levin & Munksgaard, pp. 57-62.

Schumacher, R. (1958) L’enluminure d’Echternach: art européen, Les Cahiers luxembourgeois, vol. 30, nr. 6, pp. 181-195.

Spang, P. (1958) La bibliothèque de l’abbaye d’Echternach, Les Cahiers luxembourgeois, vol. 30, nr. 6, pp. 139-163.

Talbot, C.H. (1954) The Anglo-Saxon Missionaries in Germany. Being the Lives of SS. Willibrord, Boniface, Sturm, Leoba and Lebuin, together with the Hodoeporicon of St. Willibald and a selection of the Correspondence of Boniface, [vertaald en geannoteerd], Londen-New York, 1954, 234pp.

Verlinden, C. (1928) Het evangelieboek van Maaseik, Limburg, vol. 11, p. 34.

Vriens, H. (2016) De Codex Eyckensis, een kerkschat. De waardestelling van een 8ste eeuws Evangeliarium in Maaseik, onuitgegeven master scriptie Kunstwetenschappen, KU Leuven.

Wouters, J., G. Gancedo, A. Peckstadt, en L. Watteeuw, L. (1990) The Codex Eyckensis: an illuminated manuscript on parchment from the 8th century: Laboratory investigation and removal of a 30 year old PVC lamination, ICOM triennial meeting. ICOM triennial meeting. Dresden, 26-31 August 1990, Preprints: pp. 495–499.

Wouters, J., G. Gancedo, A. Peckstadt en L. Watteeuw (1992) The conservation of the Codex Eyckensis: the evolution of the project and the assessment of materials and adhesives for the repair of parchment, The Paper Conservator 16, pp. 67-77.

Wouters, J., A. Peckstadt en L. Watteeuw (1995) Leafcasting with dermal tissue preparations: a new method for repairing fragile parchment and its application to the Codex Eyckensis, The Paper Conservator 19, pp. 5-22.

Wouters, J., Watteeuw, L., Peckstadt, A. (1996) The conservation of parchment manuscripts: two case studies, ICOM triennial meeting, ICOM triennial meeting. Edinburgh, 1-6 September 1996, London, James & James, pp. 529-544.

Wouters, J., B. Rigoli, A. Peckstadt en L. Watteeuw, L. (1997) Un matériel nouveau pour le traitement de parchemins fragiles, Techné: Journal of the Society for Philosophy and Technology, 5, pp. 89-96.

Zimmerman, E.H. (1916) Vorkarolingische Miniaturen, Deutscher Verein für Kunstwissenschaft III, Sektion, Malerei, I. Abteilung, Berlin, pp. 66-67; 128; 142-143, 303-304.