使用者:空間的拓荒者/試驗場/3

| Sensory processing disorder | |

|---|---|

| |

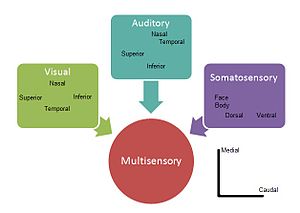

| Example of how visual, auditory and somatosensory information merge into multisensory integration representation in the superior colliculus | |

| 分類和外部資源 |

感覺統合失調 (SPD;也稱作 感覺一體化功能障礙)的一個條件存在時 感官一體化 是不充分的處理,以便提供適當的答覆的要求的環境。

的 感覺 提供信息的各種方式—視覺, 試鏡時, 觸覺, 嗅覺, 味道, 本體感覺, 前庭系統—人類需要的功能。 感覺處理障礙的特點是 顯著 問題的組織的感覺從未來的身體和環境和表現的困難表現在一個或多個主要領域的生活:生產力、 休閒 和 玩[1] 或 活動的每日生活.[2] 不同的人遇到各種各樣的困難時處理輸入來自各種各樣的 感覺,特別是觸(例如,發現織物癢,很難磨損,而其他人不這樣做),前庭(例如,經歷運動病的話,騎著一輛車)和本體(具有難度等級的部隊要舉行一筆為了寫)。

感覺一體化 的定義是通過職業治療師 安娜讓艾爾 在1972年的"神經系統過程中,組織的感覺從自己的身體和從環境,使得能夠使用的體內的有效的環境"。[3][4] 儘管它的支持者,它不是廣泛公認為一個診斷的醫療保健從業人員。

分類

[編輯]感覺處理疾病可分為三大類: 感官調症的, 感覺基礎的運動障礙 和 感官的歧視障礙 (因為定義中的診斷分類的精神健康和發育障礙的在嬰兒和兒童早期的)。[5][6][7]

感覺調症(貼片)

[編輯]感覺調製指的是一個複雜的中樞神經系統過程中[8] 通過它的神經信息,傳達的信息有關的強度、頻率、時間、複雜性和新穎的感官刺激的調整。[9] 那些貼片前的困難處理的程度、持續時間、頻率,等等, 信息和可能表現出行為與一個可怕或焦慮的模式、消極的或頑固行為,自行吸收行為是難以接觸,或創造性或積極尋求的感覺。[10]

貼包括三個子類型:

- 感覺過的響應

- 感覺下響應度

- 感覺熱衷/尋求

感覺-根據機障礙(SBMD)

[編輯]感覺-根據機動亂顯示了馬達出那就是混亂的結果不正確處理的感官信息影響 的姿勢控制 的挑戰,造成體位性障礙,或 發展協調障礙的。[11]

該SBMD子類型是:

- 運動障礙

- 姿勢障礙

感覺歧視性障礙(SDD)

[編輯]感覺歧視的障礙涉及到的不正確處理的感官信息。 不正確處理的 視覺 或 聽覺 輸入,例如,可以看出,在漫不經心、混亂和貧困學校的表現。

SDD子類型是:

- 視覺

- 聽覺

- 觸覺

- 味道

- 氣味

- 位置/運動

- Interoception的。

跡象和症狀

[編輯]症狀可能各不相同,根據疾病的種類和子類型。 SPD可以影響一個意識或多種感覺。 雖然許多人本可以一個或兩個症狀、感官處理的障礙已經有一個明確的功能影響的人的生命。

標誌過的響應

[編輯]- 不喜歡的紋理諸如那些被發現在織物、食品、整理的產品或其他材料發現,在日常生活,其中大多數人不會做出反應。

- 避免人群以及嘈雜的地方

- 運動病的 沒有醫療原因

- 拒絕接吻擁抱,或者擁抱由於負面經驗的觸摸的感覺(不要混淆的膽怯或社會困難)

- 嚴重的不適、疾病或威脅致通過正常的聲音,燈光,運動、氣味、品味、或甚至是內在的感覺如心跳。

- 挑食

- 睡眠障礙 (醒來由微小的聲音,問題得到睡覺,因為感覺載)

- 困難與平靜的自我感覺不斷受到壓力

跡象的響應度

[編輯]- 難醒來

- 呆滯和缺乏響應能力

- 缺乏認識的疼痛或其他人

- 顯而易見的耳聾甚至當聽覺功能已經過測試

- 困難與衛生間訓練,缺乏對被弄濕或被弄髒的

感覺渴望

[編輯]- 坐立不安

- 尋求或作出響,令人不安的聲音

- 爬,跳躍,而崩潰

- 尋求"極端"的感覺

- 抽吸或咬手指,服裝,鉛筆,等等。

- 衝動

感覺運動基礎的問題

[編輯]感覺歧視問題

[編輯]- 事情不斷下降

- 難敷料和飲食

- 不適當的使用武力處理對象

其他跡象和症狀

[編輯]- 不良的綜合平衡和rightening的反應

- 低肌肉模式伸對重力和屈與重的肌肉系統

- 可憐的核心音

- 低姿勢控制

- 可憐的 眼球震顫

- 存在的不綜合的反應如 ATNR

- 乾眼睛跟蹤

- 可憐的觸覺 astereognosis

- 不足電機、觀念或工程實踐

- 困難與規劃運動使用反饋信息

- 困難與規劃運動使用的前饋信息

的原因

[編輯]中腦和腦幹區域中樞神經系統的早期中心中的處理途徑感官一體化,[12] 這些大腦區域中涉及過程,包括協調、注意力,興奮,和自主的功能。 之後的感官信息,通過這些中心,然後傳送到大腦區域負責的情緒,記憶,和更高水平的認知功能。 感官處理的障礙不僅影響的解釋和反應,刺激在腦區域,但影響幾個較高的職能。 損害在任何大腦的一部分涉及在感官處理可能會導致難以充分處理的刺激,在功能方式。

目前的研究感覺處理的重點是尋找遺傳和神經系統的原因SPD。 腦電圖[13] 和測 的事件相關潛力 (ERP)是傳統上用來探索背後的原因的行為,觀察到在SPD。 一些擬議的根本原因的目前的研究是:

- 差異觸覺和聽覺超過響應出示適中的遺傳影響、與觸過的響應表明更大的遺傳性。 二元的遺傳分析提出不同的遺傳因素的個體差異的聽覺和觸覺SOR.[14]

- 人們感覺處理赤字較少的感覺 門(電) 比典型的科目。[15][16]

- 人們有感覺過的響應可能有所增加 D2受 的 紋,關係到厭惡的觸覺刺激和減少習慣的。 在動物模型,產前壓力,大大增加的觸覺避免。[17]

- 研究使用事件相關潛力(Erp)在兒童所感覺過的響應亞型發現的非典型的神經整合的感官輸入。 不同的神經發電機可以被激活在一個較早的階段的感官信息處理在人SOR比通常開發中國家個人。 自動關聯的因果關係相關的感官輸入出現在這一早期的感官知覺階段可能不適當地在兒童與SOR. 一個假設是感官的刺激可能激活一個高級別的系統,額葉皮層,涉及關注和認知處理,而不是自動一體化的感官刺激觀察到在一般開發中國家成年人的聽覺皮質。[18]

- 最近的研究發現一個異常的 白質 的微結構在兒童與SPD,較典型的兒童和那些與其他神經系統疾病,例如自閉症和多動症。[19][20]

研究

[編輯]診斷

[編輯]感官處理的障礙是當前公認的 診斷分類的精神健康和發育障礙的嬰兒和幼兒 (DC:0-3)和不被承認為一個 精神紊亂 的醫療手冊,如 國際疾病分類-10[21] 或 DSM-5.[22]

診斷主要是通過使用標準化測試、標準化的問卷調查,專家觀測尺度,並免費播放觀察處一個 職業治療 的健身房。 觀察的功能性活動可以在學校和家庭。 一些尺度,不是專門用於社會民主黨利用評價來衡量的視覺功能、神經學和電動機技能。[23]

根據國家、診斷是由不同的專業人員,例如 職業治療師中, 心理學家、學專家、 理療醫師 和/或 言語和語言理療師.[24] 在某些國家建議具有充分的心理和神經系統評價,如果症狀是嚴重的。

標準化測試

[編輯]- 感覺整合和實踐考試(SIPT)

- DeGangi-伯克的測試感覺一體化(TSI)

- 測試的感覺功能在嬰兒(TSFI)[25]

標準化問卷調查

[編輯]其他的測試

[編輯]- 臨床觀察的電動機技能和姿勢(譜曲)[29]

- 發展測試視覺感知的:第二版(DTVP-2)[30]

- 啤酒–Buktenica發展測試的視覺運動一體化,第6版(比里自願)

- 米勒功能和參與的尺度

- Bruininks–Oseretsky測試的機動能力,第二版(BOT-2)[31]

- 行為的評價清單的執行功能(簡短的)[32][33]

治療

[編輯]幾個治療方法已經發展到治療SPD。

感覺整合療法

[編輯]

主要形式的感覺整合療法是一種類型的職業治療,地方兒童在一個房間專門設計,以刺激和挑戰的所有 感覺的。

在本屆會議期間,治療師密切合作,與兒童提供一個級別的感官刺激的兒童可以應付,並鼓勵內的移動房間。 感覺一體化的治療是由四個主要原則:

- 只是右的挑戰(兒童必須能夠成功地迎接挑戰,提出了通過好玩的活動)

- 適應性反應(兒童適應他的行為與新的和有用的戰略,在應對挑戰提出)

- 積極參與(《兒童將要參與,因為活動是有趣)

- 兒童針(孩子的偏好用於發起治療的經驗,在本屆會議)

感覺處理治療

[編輯]這種療法的保留所有上述四項原則並補充說:[34]

- 強(人出席的治療每日的一段延長的時間)

- 發展辦法(治療師可以適應發育年齡的人,與實際年齡)

- 測系統的評價(所有客戶進行評估之前和之後)

- 過程驅動與活動驅動的(治療師側重於"剛剛好"的情感連接和進程加強了關係)

- 父母教育(父母教育課程計劃進入治療過程)

- "生活樂趣"(幸福的生活是治療的主要目標,達到通過社會參與、自我管制和自尊)

- 組合最佳做法的干預措施(往往伴隨著綜合監聽系統療法,落地時候,媒體和電子媒體,例如微軟、任天堂Wii遊戲機、誠II機培訓和其他人)

其他的方法

[編輯]這些治療(例如感覺運動處理)有一個有疑問的理由和沒有經驗證據。 其他治療方法(例如, 三稜鏡的鏡頭的、 身體鍛鍊,和 聽覺一體化的訓練)已經研究與小積極成果,但些結論可以作出有關他們由於方法學問題的研究。[35] 雖然可仿效的治療方法已經描述和有效成果的措施都是已知的,差距存在的相關知識的感覺集成和功能障礙治療。[36] 經驗性的支持是有限的,因此系統地評估是必要的,如果這些干預措施的使用。[37]

兒童與防-反應可能會暴露在強烈的感覺如撫摸刷、振動或摩擦。 玩可能涉及的材料範圍,以刺激的感覺如玩團或手指畫。

兒童超反應可能暴露於和平的活動,包括安靜和溫柔的音樂搖擺在一個柔和的燈光的房間。 對待,並獎勵可以用來鼓勵兒童容忍的活動,他們通常會避免的。

雖然職業治療師使用的一種感覺一體化的參照框架的工作增加一個孩子的能力,以充分過程的感官輸入,其他職業治療師可以注重環境的住宿,父母和學校工作人員可以使用,以提高兒童在家庭、學校和社區。[38][39] 這些可包括選擇軟、標記免費服裝,避免螢光燈照明,並提供耳塞的"緊急"使用(諸如消防演練中)。

成年人

[編輯]有越來越多的證據基礎,這點以及支持這一概念成年人也表現出的跡象的感官處理的困難。 在聯合王國早期的研究和改進的臨床結果,對客戶的評估作為具有感官處理的困難是指示,治療可能是適當的治療。[40] 成人的客戶展示一系列的介紹,包括 自閉症 和 阿斯伯格綜合症,以及 發展協調障礙 和一些 精神健康困難的。[41] 治療師的建議,這些介紹可能出現的困難的成年人感覺的處理遇到困難,試圖進行談判的挑戰和需求的參與日常生活。[42] 重要的是當治療人不僅僅集中在感覺調節,而且還幫助他們發展和維護社會的支持。 的成年人感覺了響應具有很高的相關性焦慮和抑鬱症的水平相比的成年人沒有感覺過的響應能力。 這是關係到所感覺到缺乏社會的支持者。[43] 官處理的障礙也可以與相關的睡眠質量的成年人。 這種關聯可以看出,特別是在成年人低神經系統的閾值(感官的靈敏度和感官的迴避)的。 這些人都更靈敏觸覺、聽覺和視覺刺激這往往影響他們的睡眠質量。

流行病學

[編輯]據估計,達到16.5%的小學學齡兒童本升高SOR行為的觸覺或聽覺的方式。[44] 然而,這一數字可能是一個低估的感覺過的響應率,因為這項研究沒有包括發展障礙兒童或那些交付早產,他們更有可能本。

這圖是,儘管如此,更大比以前的研究與小型樣本顯示:估計5-13%的小學學齡兒童。[45] 發病率,對剩餘的子類型的是目前未知的。

關係到其他疾病

[編輯]因為 共患 條件是共同的感覺一體化問題,一個人可能有其他條件。 人接受診斷的感覺處理障礙也可能有跡象的焦慮的問題,注意力缺陷多動障礙,[46] 食物不容忍、行為障礙和其他障礙。

自閉症障礙和困難的感覺處理

[編輯]感覺處理障礙是一種常見的病與 泛自閉症障礙[47][48][49][50][51][52][53] ,現在是包括作為部分的症狀在DSMV的。

異常高的同步性之間感覺皮質參與的看法和皮層下的地區中轉的信息,從的感覺器官的皮層是指作為具有中心作用過敏症和其他感官症狀,確泛自閉症障礙。[54] 感覺調製已經在主要的亞型研究。 差異大為響應(例如,步行到的事情),比為過分的響應(例如,窘迫從很大的噪音)或感官尋求(例如,有節奏的運動).[55] 的答覆可能更常見的兒童:對研究發現,自閉症兒童有受損的 觸覺感知 ,同時自閉症的成人沒有。[56]

感官體驗的調查表已經發展到幫助識別感官處理模式的兒童可以擁有自閉症。[57][58]

多動症

[編輯]據推測,SPD可能會被誤診為人關注的問題。 例如,一名學生失敗重複已經說在類(由於無聊或分心)可以被稱為評價的感覺一體化功能障礙。 學生可能會隨後將評價通過職業治療師,以確定為什麼他們有困難的專注和出席,或許也是評估一個 聽力 或 語言病理學家 對於聽覺的處理問題或語言上處理的問題。 同樣地,兒童可能被錯誤地標記為"注意缺陷多動症 (ADHD)",因為衝動已觀察到,在實際上這種衝動是有限的感覺尋求或避免。[59][60] 一個孩子可能經常跳出自己的座位在類儘管多次警告和威脅,因為他們可憐的本體(身體意識),導致他們失去自己的座位,以及它們的憂慮這種潛在的問題導致它們,以避免休息時可能的。 如果同樣的孩子能繼續坐在座位上後,被給定一個可充氣的崎嶇不平的墊當在(其中給他們更多的感官輸入),或者,能夠保持坐在家裡或在一個特定的課堂而不是在他們的主要教室,這是一個跡象,更多的評估是需要確定導致他們的衝動。

其他併發症

[編輯]各種條件可能涉及SPD,例如 強迫症,[61] 精神分裂症,[62][63][64] 琥珀半醛脫氫酶缺時,[65] 主要 遺尿症,[66] 醇產前暴露,以 學習困難的 和患有 創傷性的大腦損傷[67] 或曾有 人工耳蝸的 放置。[68] 和可能有的遺傳條件,例如 脆弱的綜合症狀X.

爭議

[編輯]有人擔心關於有效的診斷。 SPD不包括 帝斯曼-5 或 ICD-10,最廣泛使用診斷的來源中的醫療保健。 美國兒科學會國家,沒有普遍接受的框架用於診斷和建議告誡不要使用任何"感覺"類型的治療,除非作為一部分的一個全面的治療計劃。[69]

手冊

[編輯]SPD是在 斯坦利格林斯潘's 診斷手冊對於嬰兒和幼兒 ,並為 監管疾病的感官處理 一部分 的零三的診斷分類的。[70] 但是不承認在該手冊 ICD-10 或在最近更新的 DSM-5.[71] 但是,不尋常的反應性的感官輸入或不尋常的感興趣感覺方面是作為一個可能的,但沒有必要的標準診斷患有自閉症的。[72]

誤診

[編輯]一些國家,感覺處理障礙是一個獨特的診斷,而其他人則認為的差異感覺的響應,設有其他的診斷和它不是一個獨立的診斷。[73] 的神經科學家 大衛Eagleman 提議,SPD表現形式可以是 通感、感知的情況 感覺 混合。[74] 具體地說,Eagleman建議,而不是一個感官輸入"連接到[個人]色區域[在腦],這是連接的一個區域涉及疼痛或厭惡或者噁心"。[75][76][77]

研究人員已經描述了一種可治療的繼承了 過度刺激感官障礙 ,以滿足診斷標準兩者注意缺陷障礙和感官一體化功能障礙。[78]

研究

[編輯]超過130的文章上的感官一體化已經發表在對等審查(大部分是職業治療)的期刊。[來源請求] 困難的設計進行雙盲研究的感覺一體化功能障礙已處理過 寺 和其他人。[來源請求]

歷史

[編輯]感覺處理疾病第一次被詳通過職業治療師 安娜讓艾爾 (1920-1989). 根據艾爾的著作,個人與社民黨將有一個能力下降的組織的感官信息,因為它涉及在通過 的感覺.[79]

原始模型

[編輯]艾爾的理論框架,為什麼她叫感覺一體化是發達後的六個因素的分析研究的人口有學習障礙的兒童、感知機殘疾和正常發育的兒童。[80] 艾爾創建的以下 nosology 根據該模式,出現在她的因素的分析:

- 運動障礙:貧窮的 運動規劃 (更多的有關前庭系統和本體感受)

- 可憐的雙邊融合:使用不當的體兩側的同時

- 觸覺的防禦:消極反應,以觸覺刺激

- 視覺感知的赤字:貧窮的形式和空間知覺和視覺的動機的功能

- Somatodyspraxia:貧窮的運動規劃(關於貧窮的信息來自的觸覺和本體系統)

- 聽覺語言問題

兩個視覺和聽覺的語言缺陷被認為具有強烈的認知部件和脆弱的關係為基礎的感官處理赤字,所以他們不認為中央赤字在許多型號的感官處理。

1998年,穆里進行的一項研究10,000集的數據,每個代表一個單獨的孩子。 她進行確證性和探索性的因素的分析,並發現了類似的模式的赤字有她的數據作為艾爾斯所做的。[81]

象限模型

[編輯]鄧恩的nosology使用了兩個標準:[82] 響應的類型(被動vs活動),並 感閾值 的界刺激(最低或最高)建立4個子類型或象限:[83]

- 高神經系統的閾值

- 低登記:高的閾值與被動反應。 個人不上感覺,因此參加被動的行為。[84]

- 感覺尋求:高閾值和積極的響應。 那些積極尋找一位富有感官填補的環境。

- 低神經系統的閾值

- 對刺激的敏感性:低閾值與被動反應。 個人變得心煩意亂和不舒服的時候暴露出來的感覺,但不積極限制或避免接觸到的感覺。

- 感覺避免:低閾值和積極的響應。 個人積極限制他們接觸到的感覺,因此高的自我監管機構。

感覺處理模型

[編輯]在米勒的nosology"感官一體化功能障礙"改名為"感官處理的障礙",以促進協調研究工作與其他領域,例如神經病學因為"一詞的使用感覺融合通常適用於一neurophysiologic蜂窩進程,而不是一個行為響應感官輸入作為意味著通過艾瑞斯"的。 目前nosology的感官處理的障礙是由米勒,基於神經系統的基本原則。

其他模型

[編輯]各種各樣的方法已經納入的感覺,以影響學習和行為。

- 警報的程序的自我管制是一種補充做法,鼓勵知識的警覺性,經常使用的感覺戰略,以支持學習和行為。

- 其他的辦法主要是使用被動感官體驗或感官刺激根據具體協議,如Wilbarger辦法和前庭-動眼神經協議。

也參看

[編輯]參考文獻

[編輯]- ^ Sensory processing disorders and social participation. Am J Occup Ther. 2010, 64 (3): 462–73. PMID 20608277. doi:10.5014/ajot.2010.09076.

- ^ Sensory Processing Disorder Explained. SPD Foundation.

- ^ Ayres, A. Jean. Sensory integration and learning disorders. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services. 1972. ISBN 0-87424-303-3. OCLC 590960.

- ^ Ayres AJ. Types of sensory integrative dysfunction among disabled learners. Am J Occup Ther. 1972, 26 (1): 13–8. PMID 5008164.

|author=和|last=只需其一 (幫助) - ^ Concept evolution in sensory integration: a proposed nosology for diagnosis (PDF). The American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2007, 61 (2): 135–40. PMID 17436834. doi:10.5014/ajot.61.2.135.

- ^ Perspectives on sensory processing disorder: a call for translational research. Front Integr Neurosci. 2009, 3: 22. PMC 2759332

. PMID 19826493. doi:10.3389/neuro.07.022.2009.

. PMID 19826493. doi:10.3389/neuro.07.022.2009.

- ^ Sensory integration therapies for children with developmental and behavioral disorders. Pediatrics. June 2012, 129 (6): 1186–9. PMID 22641765. doi:10.1542/peds.2012-0876.

- ^ Parasympathetic functions in children with sensory processing disorder (PDF). Front Integr Neurosci. 2010, 4: 4. PMC 2839854

. PMID 20300470. doi:10.3389/fnint.2010.00004.

. PMID 20300470. doi:10.3389/fnint.2010.00004.

- ^ Miller, L. J.; Reisman, J. E.; McIntosh, D. N; Simon, J. S. S. Roley, E. I. Blanche, & R. C. Schaff , 編. An ecological model of sensory modulation: Performance of children with fragile X syndrome, autistic disorder, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and sensory modulation dysfunction (PDF). Understanding the nature of sensory integration with diverse populations (Tucson, AZ:: Therapy Skill Builders). : 75–88 [2013-07-26]. ISBN 9780761615156. OCLC 46678625.

- ^ Phenotypes within sensory modulation dysfunction (PDF). Compr Psychiatry. 2011, 52 (6): 715–24. PMID 21310399. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2010.11.010.

- ^ Development of multisensory reweighting is impaired for quiet stance control in children with developmental coordination disorder (DCD). PLOS ONE. 2012, 7 (7): e40932. PMC 3399799

. PMID 22815872. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0040932.

. PMID 22815872. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0040932.

- ^ Stein BE, Stanford TR, Rowland BA. The neural basis of multisensory integration in the midbrain: its organization and maturation. Hear. Res. December 2009, 258 (1–2): 4–15. PMC 2787841

. PMID 19345256. doi:10.1016/j.heares.2009.03.012.

. PMID 19345256. doi:10.1016/j.heares.2009.03.012.|author=和|last=只需其一 (幫助) - ^ Validating the diagnosis of sensory processing disorders using EEG technology. Am J Occup Ther. 2007, 61 (2): 176–89. PMID 17436840. doi:10.5014/ajot.61.2.176.

- ^ Goldsmith, H. H.; Van Hulle, C. A.; Arneson, C. L.; Schreiber, J. E.; Gernsbacher, M. A. A population-based twin study of parentally reported tactile and auditory defensiveness in young children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2006-06-01, 34 (3): 393–407. ISSN 0091-0627. PMC 4301432

. PMID 16649001. doi:10.1007/s10802-006-9024-0.

. PMID 16649001. doi:10.1007/s10802-006-9024-0.

- ^ Maturation of sensory gating performance in children with and without sensory processing disorders. Int J Psychophysiol. May 2009, 72 (2): 187–97. PMC 2695879

. PMID 19146890. doi:10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2008.12.007.

. PMID 19146890. doi:10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2008.12.007.

- ^ Comparison of sensory gating to mismatch negativity and self-reported perceptual phenomena in healthy adults (PDF). Psychophysiology. July 2004, 41 (4): 604–12. PMID 15189483. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8986.2004.00191.x.

- ^ Sensory processing disorder in a primate model: evidence from a longitudinal study of prenatal alcohol and prenatal stress effects (PDF). Child Dev. 2008, 79 (1): 100–13. PMID 18269511. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01113.x.

- ^ An exploratory event-related potential study of multisensory integration in sensory over-responsive children (PDF). Brain Res. June 2010, 1321: 393–407. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2010.01.043.

- ^ Owen, Julia P.; Marco, Elysa J.; Desai, Shivani; Fourie, Emily; Harris, Julia; Hill, Susanna S.; Arnett, Anne B.; Mukherjee, Pratik. Abnormal white matter microstructure in children with sensory processing disorders. NeuroImage: Clinical. 2013, 2: 844–853. ISSN 2213-1582. doi:10.1016/j.nicl.2013.06.009.

- ^ Chang, Yi-Shin; Owen, Julia P.; Desai, Shivani; Hill, Susanna S.; Arnett, Anne B.; Harris, Julia; Marco, Elysa J.; Mukherjee, Pratik. Autism and Sensory Processing Disorders: Shared White Matter Disruption in Sensory Pathways but Divergent Connectivity. PLOS ONE. 2014, 9: e103038. PMC 4116166

. PMID 25075609. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0103038.

. PMID 25075609. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0103038.

- ^ ICD 10

- ^ Lucy Jane Miller. Final Decision for DSM-V. Sensory Processing Disorder Foundation. [3 October 2013].

|author=和|last=只需其一 (幫助) - ^ Kinnealey, Moya; Miller, Lucy J. Helen L Hopkins; Helen D Smith; Helen S Willard; Clare S Spackman , 編. Sensory integration and learning disabilities (PDF). Willard and Spackman's occupational therapy 8 (Philadelphia: Lippincott, cop.). 1993: 474–489 [23 July 2013]. ISBN 9780397548774. OCLC 438843342.

- ^ Course information and booking. Sensory Integration Network. [23 July 2013].

- ^ Assessments of sensory processing in infants: a systematic review. Dev Med Child Neurol. April 2013, 55 (4): 314–26. PMID 23157488. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8749.2012.04434.x.

- ^ The sensory profile: a discriminant analysis of children with and without disabilities. Am J Occup Ther. April 1998, 52 (4): 283–90. PMID 9544354. doi:10.5014/ajot.52.4.283.

- ^ Development of the Sensory Processing Measure-School: initial studies of reliability and validity (PDF). Am J Occup Ther. 2007, 61 (2): 170–5. PMID 17436839. doi:10.5014/ajot.61.2.170.

- ^ Glennon, Tara J.; Miller Kuhaneck, Heather; Herzberg, David. The Sensory Processing Measure–Preschool (SPM-P)—Part One: Description of the Tool and Its Use in the Preschool Environment. Journal of Occupational Therapy, Schools, & Early Intervention. 2011, 4 (1): 42–52. ISSN 1941-1243. doi:10.1080/19411243.2011.573245.

- ^ Wilson B1, Pollock N, Kaplan BJ, Law M, Faris P. Reliability and construct validity of the Clinical Observations of Motor and Postural Skills.. Am J Occup Ther. September 1992, 46 (9): 775–83. PMID 1514563. doi:10.5014/ajot.46.9.775.

|author=和|last=只需其一 (幫助) - ^ The Validity and Reliability of Developmental Test of Visual Perception-2nd Edition (DTVP-2). Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. January 2013, 33 (4): 426–39. PMID 23356245. doi:10.3109/01942638.2012.757573.

- ^ Review of the Bruininks–Oseretsky Test of Motor Proficiency, Second Edition (BOT-2). Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 2007, 27 (4): 87–102. PMID 18032151. doi:10.1080/j006v27n04_06.

- ^ Behavior rating inventory of executive function. Child Neuropsychol. September 2000, 6 (3): 235–38. PMID 11419452. doi:10.1076/chin.6.3.235.3152.

- ^ Confirmatory factor analysis of the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function (BRIEF) in a clinical sample. Child Neuropsychol. December 2002, 8 (4): 249–57. PMID 12759822. doi:10.1076/chin.8.4.249.13513.

- ^ Miller, Dr. Lucy Jane. The "So What?" of Sensory Integration Therapy: Joie de Vivre (pdf). Sensory Solutions. Sensory Processing Disorder Foundation. 2013 [11 January 2016].

- ^ Baranek GT. Efficacy of sensory and motor interventions for children with autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2002, 32 (5): 397–422. PMID 12463517. doi:10.1023/A:1020541906063.

|author=和|last=只需其一 (幫助) - ^ Occupational therapy using a sensory integrative approach for children with developmental disabilities. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2005, 11 (2): 143–8. PMID 15977314. doi:10.1002/mrdd.20067.

- ^ Somatosensory stimulation interventions for children with autism: literature review and clinical considerations. Can J Occup Ther. 2007, 74 (5): 393–400. PMID 18183774. doi:10.2182/cjot.07.013.

- ^ Nancy Peske; Lindsey Biel. Raising a sensory smart child: the definitive handbook for helping your child with sensory integration issues. New York: Penguin Books. 2005. ISBN 0-14-303488-X. OCLC 56420392.

- ^ Sensory Checklist (PDF). Raising a Sensory Smart Child. [16 July 2013].

- ^ The Effectiveness of Sensory Integration Therapy to Improve Functional Behaviour in Adults with Learning Disabilities: Five Single-Case Experimental Designs. Brit J. Occupational Therapy. February 2005, 68 (2): 56–66.

- ^ Brown, Stephen; Shankar, Rohit; Smith, Kathryn. Borderline personality disorder and sensory processing impairment. Progress in Neurology and Psychiatry. 2009, 13 (4): 10–16. ISSN 1367-7543. doi:10.1002/pnp.127.

- ^ Sensory processing disorder in mental health. Occupational Therapy News: 28–29.

- ^ Kinnealey, Moya; Patten Koenig, Kristie; Smith, Sinclair. Relationships Between Sensory Modulation and Social Supports and Health-Related Quality of Life. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2011, 65 (3): 320–327. PMID 21675338. doi:10.5014/ajot.2011.001370.

- ^ Carter, A. S.; A. Ben-Sasson; M. J. Briggs-Gowan. Sensory Over-Responsivity in Elementary School: Prevalence and Social-Emotional Correlates (PDF). J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2009, 37 (5): 705–716. PMID 19153827. doi:10.1007/s10802-008-9295-8.

- ^ Ahn, RR.; Miller, LJ.; Milberger, S.; McIntosh, DN. Prevalence of parents' perceptions of sensory processing disorders among kindergarten children. (PDF). Am J Occup Ther. 2004, 58 (3): 287–93. PMID 15202626. doi:10.5014/ajot.58.3.287.

- ^ Ghanizadeh A. Sensory processing problems in children with ADHD, a systematic review. Psychiatry Investig. June 2011, 8 (2): 89–94. PMC 3149116

. PMID 21852983. doi:10.4306/pi.2011.8.2.89.

. PMID 21852983. doi:10.4306/pi.2011.8.2.89.|author=和|last=只需其一 (幫助) - ^ Sensory processing subtypes in autism: association with adaptive behavior. J Autism Dev Disord. January 2010, 40 (1): 112–22. PMID 19644746. doi:10.1007/s10803-009-0840-2.

- ^ Sensory processing in children with and without autism: a comparative study using the short sensory profile. Am J Occup Ther. 2007, 61 (2): 190–200. PMID 17436841. doi:10.5014/ajot.61.2.190.

- ^ Sensory correlations in autism. Autism. March 2007, 11 (2): 123–34. PMID 17353213. doi:10.1177/1362361307075702.

- ^ Multisensory processing in children with autism: high-density electrical mapping of auditory-somatosensory integration. Autism Res. October 2010, 3 (5): 253–67. PMID 20730775. doi:10.1002/aur.152.

- ^ Anxiety disorders and sensory over-responsivity in children with autism spectrum disorders: is there a causal relationship?. J Autism Dev Disord. December 2010, 40 (12): 1495–504. PMC 2980623

. PMID 20383658. doi:10.1007/s10803-010-1007-x.

. PMID 20383658. doi:10.1007/s10803-010-1007-x.

- ^ Talent in autism: hyper-systemizing, hyper-attention to detail and sensory hypersensitivity. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. May 2009, 364 (1522): 1377–83. PMC 2677592

. PMID 19528020. doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0337.

. PMID 19528020. doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0337.

- ^ Sensory processing in autism: a review of neurophysiologic findings. Pediatr. Res. May 2011, 69 (5 Pt 2): 48R–54R. PMC 3086654

. PMID 21289533. doi:10.1203/PDR.0b013e3182130c54.

. PMID 21289533. doi:10.1203/PDR.0b013e3182130c54.

- ^ Increased Functional Connectivity Between Subcortical and Cortical Resting-State Networks in Autism Spectrum Disorder. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015, 72: 767. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0101.

- ^ A meta-analysis of sensory modulation symptoms in individuals with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2008, 39 (1): 1–11. PMID 18512135. doi:10.1007/s10803-008-0593-3.

- ^ Neuropsychologic functioning in children with autism: further evidence for disordered complex information-processing. Child Neuropsychol. 2006, 12 (4–5): 279–98. PMC 1803025

. PMID 16911973. doi:10.1080/09297040600681190.

. PMID 16911973. doi:10.1080/09297040600681190.

- ^ Sensory Experiences Questionnaire: discriminating sensory features in young children with autism, developmental delays, and typical development. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. June 2006, 47 (6): 591–601. PMID 16712636. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01546.x.

- ^ Psychometric validation of the Sensory Experiences Questionnaire. Am J Occup Ther. 2011, 65 (2): 207–10. PMC 3163482

. PMID 21476368.

. PMID 21476368.

- ^ Lane, SJ.; Reynolds, S.; Thacker, L. Sensory Over-Responsivity and ADHD: Differentiating Using Electrodermal Responses, Cortisol, and Anxiety.. Front Integr Neuroscience. Mar 2010, 4. PMC 2885866

. PMID 20556242. doi:10.3389/fnint.2010.00008.

. PMID 20556242. doi:10.3389/fnint.2010.00008.

- ^ Cheng, M.; Boggett-Carsjens, J. Consider sensory processing disorders in the explosive child: case report and review.. Can Child Adolesc Psychiatr Rev. May 2005, 14 (2): 44–8. PMC 2542921

. PMID 19030515.

. PMID 19030515.

- ^ American Friends of Tel Aviv University. Childhood hypersensitivity linked to OCD. ScienceDaily. 2011.

|author=和|last=只需其一 (幫助) - ^ Impaired multisensory processing in schizophrenia: deficits in the visual enhancement of speech comprehension under noisy environmental conditions. Schizophr. Res. December 2007, 97 (1–3): 173–83. PMID 17928202. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2007.08.008.

- ^ Auditory processing in schizophrenia during the middle latency period (10–50 ms): high-density electrical mapping and source analysis reveal subcortical antecedents to early cortical deficits. J Psychiatry Neurosci. September 2007, 32 (5): 339–53. PMC 1963354

. PMID 17823650.

. PMID 17823650.

- ^ Auditory sensory dysfunction in schizophrenia: imprecision or distractibility?. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. December 2000, 57 (12): 1149–55. PMID 11115328. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.57.12.1149.

- ^ Kratz SV. Sensory integration intervention: historical concepts, treatment strategies and clinical experiences in three patients with succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase (SSADH) deficiency. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. June 2009, 32 (3): 353–60. PMID 19381864. doi:10.1007/s10545-009-1149-1.

|author=和|last=只需其一 (幫助) - ^ [Sensory integration function in children with primary nocturnal enuresis]. Zhongguo Dang Dai Er Ke Za Zhi. October 2008, 10 (5): 611–3. PMID 18947482 (中文).

- ^ Alteration of postural responses to visual field motion in mild traumatic brain injury. Neurosurgery. July 2006, 59 (1): 134–9; discussion 134–9. PMID 16823309. doi:10.1227/01.NEU.0000219197.33182.3F.

- ^ Sensory-processing disorder in children with cochlear implants. Am J Occup Ther. 2009, 63 (2): 208–13. PMID 19432059. doi:10.5014/ajot.63.2.208.

- ^ {http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/pediatrics/129/6/1186.full.pdf |title=Sensory Integration Therapies for Children With Developmental and Behavioral Disorders |format=pdf>

- ^ Infants and Toddlers Who Require Specialty Services and Supports (pdf). Department of Community Health—Mental Health Services to Children and Families.

- ^ American Psychiatric Association Board of Trustees Approves DSM-5. [15 July 2013].

- ^ Susan L. Hyman. New DSM-5 includes changes to autism criteria. AAP News. American Academy of Pediatrics. 2013 [3 October 2013].

|author=和|last=只需其一 (幫助) - ^ Joanne Flanagan. Sensory processing disorder (PDF). Pediatric News. Kennedy Krieger.org. 2009.

|author=和|last=只需其一 (幫助) - ^ Eagleman, David; Cytowic, Richard E. Wednesday is indigo blue: discovering the brain of synesthesia. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press. 2009. ISBN 0-262-01279-0. OCLC 233697438.

- ^ The blended senses of synesthesia, Los Angeles Times, Feb 20, 2012.

- ^ Pathways to seeing music: enhanced structural connectivity in colored-music synesthesia. NeuroImage. July 2013, 74: 359–66. PMC 3643691

. PMID 23454047. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.02.024.

. PMID 23454047. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.02.024.

- ^ Redefining synaesthesia?. Br J Psychol. February 2012, 103 (1): 20–3. PMID 22229770. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8295.2010.02003.x.

- ^ Hypokalemic sensory overstimulation. J Child Neurol. 2007, 22 (12): 1408–10. PMID 18174562. doi:10.1177/0883073807307095.

- ^ Ayres, A. Jean.; Robbins, Jeff. Sensory integration and the child : understanding hidden sensory challenge 25th Anniversary Edition. Los Angeles, CA: WPS. 2005. ISBN 978-0-87424-437-3. OCLC 63189804.

- ^ Bundy, Anita. C.; Lane, J. Shelly; Murray, Elizabeth A. Sensory integration, Theory and practice. Philadelphia, PA: FA Davis Company. 2002. ISBN 0-8036-0545-5.

- ^ Smith Roley, Susanne; Zoe Mailloux; Heather Miller-Kuhaneck; Tara Glennon. Understanding Ayres Sensory Integration (PDF). OT PRACTICE. 17. September 2007, 12 [19 July 2013].

- ^ Dunn, Winnie. The Impact of Sensory Processing Abilities on the Daily Lives of Young Children and Their Families: A Conceptual Model. Infants & Young Children: April 1997. April 1997, 9 (4) [2013-07-19].

- ^ Dunn W. The sensations of everyday life: empirical, theoretical, and pragmatic considerations. Am J Occup Ther. 2001, 55 (6): 608–20. PMID 12959225. doi:10.5014/ajot.55.6.608.

|author=和|last=只需其一 (幫助) - ^ Engel-Yeger, Batya; Shochat, Tamar. The relationship between sensory processing patterns and sleep quality in healthy adults. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. June 2012, 79 (3): 134–141. doi:10.2182/cjot.2012.79.3.2.

進一步閱讀

[編輯]- Sensory processing disorder. Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience – Research Topics. [24 August 2013].

[[Category:自閉症]] [[Category:神經系統疾病]] [[Category:作业疗法]] [[Category:知覺]] [[Category:感觉系统]]