美国诉黄金德案

| 美国诉黄金德案 United States v. Wong Kim Ark | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| 辩论:1897年3月5日、3月8日 判决:1898年3月28日 | |||||

| 案件全名 | United States v. Wong Kim Ark | ||||

| 引註案號 | 169 U.S. 649 18 S.Ct. 456; 42 L.Ed. 890 | ||||

| 既往案件 | 从美国加利福尼亚州北部地区法院上诉:71 F. 382 | ||||

| 法庭判决 | |||||

| 根据第十四条修正案的公民权条款,凡在美国出生的儿童即成为美国公民 | |||||

| 最高法院法官 | |||||

| |||||

| 法庭意见 | |||||

| 多数意见 | 霍里斯·格雷 联名:大卫·乔什亚·布鲁尔、亨瑞·比林斯·布朗、小乔治·席拉斯、爱德华·道格拉斯·怀特、鲁弗斯·威勒·派克汉姆 | ||||

| 不同意见 | 梅尔维尔·富勒 联名:约翰·马歇尔·哈伦 | ||||

| 约瑟夫·麦肯纳没有参与该案件。 | |||||

| 适用法条 | |||||

| 美利坚合众国宪法第十四条修正案 | |||||

美国诉黄金德案(英語:United States v. Wong Kim Ark)169 U.S. 649 (1898),是一起美国联邦最高法院判决所有美国境內出生者都是美国公民的里程碑式案例。判决在解读美利坚合众国宪法第十四条修正案的公民权条款上建立了重要的判决先例。

黄金德于1871年出生于旧金山,他的父母都是华人。一次出国旅行归来时,移民局根据1882年5月6日通过的《排华法案》拒绝他入境。黄金德为此将政府告上法庭,挑战政府拒绝承认其公民身份的做法。联邦最高法院在判决中支持了他的意见,认定根据第十四条修正案,每一位在美国出生的人都是美国公民,即使他父母是外国人亦不例外,并且这样的特权即使有联邦国会通过的法律也不能剥夺。

此案件特别突出了对公民公款中一个短语准确含义理解的分歧,即一个在美国出生的人是否符合“并受其管辖”的要求从而获得公民权。最高法院的多数意见总结认为这一短语的意思是受到美国法律的管辖。在这一基础上,第十四条修正案将被解读为赋予几乎任何在美国领土出生的人美国公民身份(即属地主义原则)。而法院对此持不同意见的两位法官则认为“并受其管辖”应该是从政治上效忠于美国,即根据血统主义(即属人主义)原则,新生儿的国籍将根据其父母的国籍来认定[1]。

研究人员在2007年的一篇对黄金德案后相关判决的法律分析文章中认为,以属地主义原则赋予公民权的概念“从来没有被最高法院严肃地质疑过,并且也由下级法院作为教条所接受”[2]:80。2010年的一篇针对公民权条款历史的评论文章指出,黄金德案判决使公民权条款“适用于在美国领土上出生的外国人士后代”,并指出最高法院“自‘非法移民’一词出现以来还从未重新审视过这一判决”[3]:332。

不过自1990年代起,长期存在的非法移民后代也能自动获得公民权这一做法随着流入美国移民数量的大量增加而引起了不少争议。法律学者表示不认同将黄金德案的判决先例应用到非法移民后代身上。国会曾先后几次试图对属地主义原则作出限制,或是通过法案来重新定义“管辖”一词,又或试图通过一条宪法修正案来推翻判决,但这些努力都没有成功。

背景

早期的美国公民权法律

美国公民权相关法律是以两个传统原则建立的:一个是“属地主义”原则,也称“普通法主义”原则;另一个是“血统主义”原则,亦称“国际公法”原则或是“国际主义”原则。根据属地主义原则或英国的普通法,一位新生儿的国籍将按其出生地来判断,无须考虑新生儿政治上是否向该国效忠或是其父母的相应情况。而在血统主义原则或国际公法原则下,新生儿的国籍将与其父母(主要是与父亲,除非是未婚生育才会与母亲)保持一致,不考虑出生地[4]:536[5]。

纵观美国历史,虽然直至内战结束后才有对公民权作出明确定义的法律[6],但以属地主义原则判断公民身份一直是占有主导地位的法律原则,而且此做法已经得到普遍接受[7][8],故所有在美国领土出生的新生儿都将自动获得公民权。唯一例外则是内战前-奴隶遭排除在外,因為他们被认为是奴隶主的财产,因而不能成为美国公民[9][10][11]。1844年纽约州有过一个以属地主义原则判定公民权的典型案例林奇诉克拉克案(Lynch v. Clarke),案中一对外国夫妇侨居在纽约市时生下了一名女婴,这个女婴就由法官根据属地主义原则判定是一位美国公民[12]。

美国公民权同样也可以通过血统主义原则获得,国会曾通过《1790年入籍法》确认了这一原则,主要是为了让身在国外美国公民的孩子也可以自动拥有公民权[13]。此外,移民美国的外国人也可以通过归化程序成为美国公民,这一过程起初只限定对“自由的白人”开放,但之后已经废除了限制[13]。

来自非洲的黑奴曾被长期排除在美国公民以外。1857年,联邦最高法院对斯科特诉桑福德案作出判决[14],认为根据宪法,所有奴隶或之前曾是奴隶的人以及他们的后代都不能成为美国公民[15]。此外,由于印第安人部落和該保留地一度不属于联邦政府的管辖范围,因此美洲原住民起初亦不獲納入美国公民之列。

第十四条修正案公民权条款

内战结束后,奴隶制被全面废除,国会颁布了《1866年民权法案》[16][17]。其中明确规定包括获得解放的奴隶在内,“除了未被征税的印第安人以外,所有在美国出生且非任何外国势力的人”都是美国公民[18]。

由于担心《1866年民权法案》中保证的公民权遭将来的国会立法废除[19],或是被法院判定违宪[20][21],法案通过后国会马上就起草了美利坚合众国宪法第十四条修正案并递交各州批准(整个过程都在1868年完成)[22]。第十四条修正案中的许多规定确立了对公民身份的宪法保证:“所有在合众国出生或归化合众国并受其管辖的人,都是合众国的和他们居住州的公民”[23][24][25]。这一公民权条款由来自密歇根州的联邦参议员雅各布·M·霍华德于1866年5月30日提出,是对众议院联席决议起草的第十四条修正案初稿的一个补充[26]。参议院对霍华德的提议展开了激烈的辩论,辩论主要集中在其谴辞用句上是否会比《1866年民权法案》产生更广泛的影响[27]。霍华德表示这一条款“只是简单地将我看来已经成为法律的内容作一次宣示,那就是根据自然法和国家法律,所有在合众国出生或归化合众国并受其管辖的人,都是合众国的公民”[26]。他也补充认为公民权的赋予“当然不包括那些外交官或是受联邦政府认可的他国官员及其家人,但是应该包括所有其他层次的人。”这一补充之后将引发国会是否一开始就打算将他国人士在美国出生的后代认定为美国公民的争议。来自宾夕法尼亚州的埃德加·科万对此表示担忧,认为放宽公民权标准可能会导致一些州涌入大量不良外来移民[28];不过来自加利福尼亚州的约翰·康纳斯则预料该州的华人总数将保持在一个很低的数字,这很大程度上是由于华人移民几乎最终总是会返回中国,而这则是因为很少会有中国的女性离开故土来到美国[29]。

威斯康星州的詹姆斯·罗德·杜利特对条款表示反对,认为放宽这一限制将导致印第安人获得公民权[30],为了解决这个问题,他提议在公民权条款中增加一句民权法案的已有内容:“不包括未被征税的印第安人”[26]。虽然大部分参议员都同意不应该赋予印第安人公民权,但其中的大部分也认为并不必要将这个问题澄清[31],因此杜利特的提议经投票被否决[32]。修正案回到众议院时没有再引起多少辩论,也没有人对参议院增加的公民权条款表示反对,修正案于1866年6月13日在众议院投票通过[33],并在1868年7月28日正式宣布通过[34]。

2006年在加州大学伯克利分校法学院担任助理教授,并在之后成为加利福尼亚州最高法院大法官的刘弘威在文章中写道,虽然公民权条款的立法历史有些“稍嫌单薄”,但其在内战后时期历史背景下的核心作用却是显而易见的[35]。一个名为宪法问责中心的进步主义智库首席法律顾问伊丽莎白·威德拉(Elizabeth Wydra)[36]认为,1866年公民权条款的支持和反对者们都认同这一条款将自动赋予所有在美国出生的人公民身份(除了外交官或入侵军队的子女)[37]。德克萨斯州副检察长詹姆斯·C·胡(James C. Ho)对此也有同样的看法[38]。艾克朗大学法学院院长理查德·艾纳斯(Richard Aynes)则表示了不同看法,他认为公民权条款产生了“其制定者始料未及的效果”[39]。

美国华人的公民权

与其他许多国家的移民一样,华人也被吸引来了美国,起初主要是因为1849年的加利福尼亚淘金潮,然后则是参与修建铁路、务农及在城市中找工作[40]:56。1868年中美两国签订《中美天津条约续增条约》(又名《蒲安臣条约》),大幅扩大了中美间贸易和移民的规模[41]。但条约中并没有涉及两国公民在对方领土上出生子女的公民权问题[42]。而对于归化(除出生外另一个获得公民权的途径)方面,条约中包括的一条规定则是:“本条约中所包含的任何内容,不得用作归化……在美国的中国人士”[43][44]。

很大程度上由于其完全不同文化习惯和价值观的影响,华人移民初到美国时面对的是相当普遍的不信任、不满和歧视。许多政治家认为华人实在是在太多方面存在如此巨大差異,以致于不但不会,更是不可能融入到美国的文化之中,并且还会对这个国家的原则和体制构成威胁[40]:57。在这种反华情绪的环境下,国会于1882年制定了《排华法案》,对来自中国的移民作出限制[45]。这一法案之后还经过了数次修改[46],如1888年的《斯科特法案》[47]和1892年的《格尔瑞法案》[48],这些都曾统称为《排华法案》。已经进入美国的华人可以继续生活,但他们没有资格入籍,并且當他们离开美国之后再回来時,需重新申请并获得批准。法案中还特别禁止了华人劳工和矿工进入或返回美国[49]:46[50]。

法院与公民权条款

在第十四条修正案通过后,黄金德案出现之前,外国人士孩童出生地公民权的问题专指华人和土著印第安人[51][52]。联邦最高法院曾在1884年的艾尔克诉威尔金斯案中裁决於保留地出生的印第安人不属于联邦政府管辖范围,因此不能够获得美国公民身份,亦不可因为之后只是离开保留地并放弃向之前的部落效忠就能成为美国公民[53][54]。

华人移民在美国出生的后代是否适用公民权条款的问题首先是在1884年的“陸天申案”(In re Look Tin Sing)中提出的[55]。陸天申[56]于1870年在加利福尼亚州蒙多西诺出生,1884年他去了一趟中国,但回美国时由于不能提供当时所规定中国移民就有的足够证明文件,他被禁止入境。这个案件在加利福尼亚州的联邦巡回法院开庭,联邦最高法院大法官史蒂芬·约翰逊·菲尔德和另外两位联邦法官审理[55]。据新罕布什爾大學历史教授露西·萨尔耶(Lucy Salyer)[57]书中所写,大法官菲尔德“向该地区所有的律师发出公开邀请,请他们就(这一案件)涉及的宪法问题发表意见”[40]:60。菲尔德关注于公民权条款中“并受其管辖”这一短语的含义,认为陸天申出生时,他的父母虽然是外国人士,但他仍然“受美国管辖”,因此大法官命令美国官员视陸天申为美国公民并允许他入境[58]。陸天申案之后并没有上诉,并且也从未被最高法院审查。1892年的另一个案件中,加利福尼亚州同一个巡回区的联邦上诉法院(即之后的第九巡回上诉法院)总结认为只要一个华人可以提供足够的证据证实他是在美国境内出生的,那么就应视其为美国公民[59]。这一案件同样没有上诉到最高法院。

1873年,联邦最高法院在屠宰场案的判决中[60]有这样的一句表述:“‘并受其管辖’旨在排除外国领事、官员和公民在美国出生的后代”[61]。不过因为该案并未涉及出生公民权的问题,所以之后法院没有考虑这一表述,并视之为一个没有任何案件先例约束力的附加说明[62][63]。

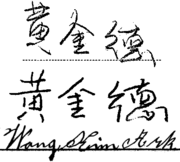

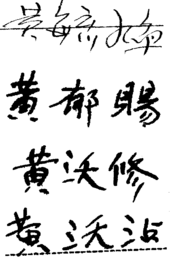

对黄金德公民权的挑战

黄金德(Wong Kim Ark[64])出生于旧金山,各种来源表明他有可能是出生于1873年[65]、1871年[66][67]或1868年[68][69]。他的父亲黄四平(Wong Si Ping,音译)和母亲李薇(Wee Lee,音译)都是来自中国的移民,而二人皆非美国公民[2]:74[49]:51。黄金德在旧金山做厨师[70]。

1890年,黄金德到中国探亲,并于同年7月回美国,这一次他的美国身份没有受到质疑,所以一路平安无事。1894年11月,他再次搭船临时前往中国,但到了次年8月回国时,他被旧金山港的移民局人员拒绝入境并予以拘留。移民局人员认为黄金德虽然出生在美国境内,但由于他的父母都是中国人,所以他也应该是中国而非美国公民[71]。

根据萨尔耶的说法,旧金山市检查官乔治·科林斯(George Collins)曾试图说服联邦司法部将一个华人出生公民权的案子上诉到联邦最高法院。他曾在1895年5至6月的《美国法律评论》上发表文章,批评之前陸潤卿案的判决以及联邦政府对挑战这一判决驻足不前。并主张以国际法的观点来解读公民权的血统主义原则[72]。最终他成功说服了“努力寻找一个可行案件并选中了黄金德案的”联邦司法部长亨瑞·富特(Henry Foote)[40]:66。

在中华公所法律代表的帮助下[40]:67,黄金德对拒绝承认他生来就是美国公民的人提出挑战,并向美国联邦地区法院发起人身保护令的呈请[73][74]。地区法院法官威廉·W·莫罗听取了双方的辩论[49]:52,这场庭辩主要围绕公民权条款中“并受其管辖”(subject to the jurisdiction thereof')五字解读以及外来人士在美国所生孩子是否属于美国公民的问题展开[75]。黄金德的律师认为其含义是“受到合众国法律的管辖”,在这样的理解下,他国公民进入美国后就应遵守其法律。这一解读也与美国从英国所继承的普通法思想相符,并且将确保所有在美国出生的人都会根据出生地原则而成为美国公民。联邦政府则声称“并受其管辖”的意思是“从政治上受合众国的管辖”。这样的解读则是来自于国际法,是根据一个孩子的父母来判断其国籍,即“血统主义”原则。根据这样的解读,由于黄金德的父母都不是美国公民,因此他也不是[76][77]。

在这以前,联邦最高法院还从未审理过有关外国人在美国生下的后代是否是美国公民的案件[62][78]。联邦政府认为黄金德所要求的美国公民权已经被最高法院在1873年的屠宰场案中排除[79][61],但地区法院法官认为该案例并不直接与本案有关,因此只有少许的参考价值[62][80],政府又提到了艾尔克诉威尔金斯案中的类似结论,但法官仍然认为缺乏足够的说服力[81][82]。

黄金德的律师援引陆天申案(In re Look Tin Sing,音译[56])中地区法院法官的意见,在最高法院没有指定一个明确方向的情况下,这一案件将对解决所有第九巡回区与黄金德情况类似人士的公民权问题起到决定性作用[83][84]。法官注意到陆天申案的判决在之后也得到了联邦上诉法院另一案件的重申,还参考了最高法院在屠宰场案判决中“只要(一个人)在美国出生或是归化,那么他就是美国的公民”这一表述[85]。他得出结论认为陆天申案判决是第九巡回区的一个有效先例。莫罗法官裁定“并受其管辖”意味着受美国法律的管辖。1896年1月3日[86][87],法官宣布黄金德是一位美国公民,原因為他在美国出生[88][89]。

联邦政府败诉后直接向最高法院提出了上诉[90][91]。据萨尔耶的说法,政府官员意识到这一案件的判决“不仅是对华裔,而且对所有在美国出生但父母是别国人士的人皆非常重要”,同时也担心如果按常规途径上诉至最高法院,那么同年11月的1896年美国总统选举将会对最高法院的判决产生影响。所以为了避免法院基于对政策的担忧而非根据案件本身来进行审理,政府选择了越过上诉法院[40]:69。1897年3月5日,双方在最高法院展开了口头辩论[92]。代表政府一方的是联邦副检察长霍尔姆斯·康拉德[93],而代表黄金德出庭的律师则是麦克斯维尔·埃瓦茨,前助理联邦司法部长J·哈伯利·阿什顿(J. Hubley Ashton)[94]和托马斯·D·里尔丹(Thomas D. Riordan)[95]。

最高法院认为,这一案件的关键问题在于“一个在美国出生的孩子父母具有中国血统,出生时两人虽然在美国有固定住所但仍然是中国皇帝的子民,他们不是任何外交官或中国皇帝的官员下属,而是来此经商,那么这个孩子是否可以根据第十四条修正案获得公民权[2]:74。”如果黄金德是美国公民,那么“国会通过旨在禁止华人,特别是华人劳工进入美国的《排华法案》将对他不适用”[96]。

法庭意见

最高法院以六比二的投票结果[97][98]裁定黄金德一出生便拥有美国公民身份,而“黄金德与生俱来的美国公民权并没有因为任何原因失去或被剥夺”[99],並于1898年3月28日正式宣布[100]。判决书由大法官霍里斯·格雷起草,另外5位大法官大卫·乔什亚·布鲁尔、亨瑞·比林斯·布朗、小乔治·席拉斯、爱德华·道格拉斯·怀特和鲁弗斯·威勒·派克汉姆联名[101]。

法院在判决中认为公民权条款应该根据英国普通法的角度来解读[102],即坚持属地主义原则[103]。普通法所认定的英籍人士即包括了几乎所有出生在其领土范围内的儿童,仅有的例外只是外国统治者或外交官的后代、在外国公共船只上出生的后代或敌对交战势力所占领土上出生的后代[104][2]:74-76。“根据普通法,认定英国国籍的基本原则就是属地主义原则,在英国出生的孩童,包括友好的外国人,都将被视为是天生的英国公民。这一原则唯一的例外只是外交官或是敌对势力的后代……第十四条修正案以清晰的表述规定了每一位在其管辖属地出生的婴儿,无论种族或肤色,只要不涉及属地主义原则的例外即是美国公民”[105]。法院的多数意见认为公民权条款中的“并受其管辖”五字只排除了普通法中所提及的三类以及“未被征税的印第安人”[53][106]。多数意见总结认为黄金德并不适用于这全部4种例外情况,也没有任何证据可以证实他在美国生活和工作以及前往中国的过程中有关联到任何外交事务[71]。

判决书中援引1812年帆船交易所诉法登案中首席大法官约翰·马歇尔的意见:“国家对其领土的管辖权必定是专属且绝对的”[107][108][109],支持了最初审理此案的地区法院法官有关“屠宰场案”中非公民父母后代公民权的判决并不构成本案具有约束性先例的意见[63]。法院认为黄金德与生俱来的公民权受第十四条修正案保护,《排华法案》中的限制对其不适用[110]。他们认为一项国会的立法不能凌驾于宪法之上,这样的法律“不能左右(宪法的)含义或是削弱其效果,而必须服从规定並予以解释及执行”[111][112]。1898年法院的裁决公布后不久,旧金山市检察官马歇尔·B·伍德沃斯(Marshall B. Woodworth)[113][114]评价道,对判决“持异议者显然没有意识到合众国作为一个主权实体,有权通过任何其认为适当的公民权法律,国际法中的相关规则并不能将美国公民认定原则限制在其单独的范围内”[115]:561。

不同意见

首席大法官梅尔维尔·富勒撰写了案件的不同意见,大法官约翰·马歇尔·哈伦联名。不同意见认为“在大多数情况下,应该要承认国际法原则的前提”[115]:560-561。他们认为美国公民权法律早在独立战争胜利后就已经与英国普通法决裂,美国人放弃了英国国籍,拒绝再向大英帝国永久效忠[116][117]。不同意见认为以血统主义原则根据新生儿的父亲判断其国籍的做法在美国独立后的法律史上更为普遍[118]。他们还根据美国与中国订立的条约以及入籍法的规定认为,“除非第十四条修正案推翻了这些条约和入籍法,华人在国内生下的孩童并不能从事实上成为美国公民”[2]:77[119][120]。

国会曾在提出第十四条修正案两个月前通过了《1866年民权法案》,其中有“除了未被征税的印第安人以外,所有在美国出生且非任何外国势力的人”都是美国公民的表述。持不同意见的两位法官据此认为公民权条款中“并受其管辖”应该也是成为美国公民的必要条件[121][122]。在其看来,过度依赖属地主义原则作为判断公民身份的决定性因素是站不住脚的,“外国人仅仅是经过我国时所生下的孩子,无论其是否有皇族血统,又无论他们是蒙古、马来或其他种族都有资格去竞选总统,而我们自己公民在海外所生的孩子卻反而没有”[1]。

两位法官还承认其他外国人的后代,包括以前的奴隶都在多年来通过属地主义原则获得了公民权,然而他们认为华人的情况仍然有所不同。因为华人巨大的文化传统差异使他们无法融入美国主流社会[119]。当年中国的法律还规定放弃向皇帝效忠将是死罪[123],而《排华法案》也令已经居留在美国的华人没有资格再寻求公民身份[124],所以对于两位法官来说真正的问题“并不是黄金德是否在美国出生或受其管辖……而是他的父母是否能够根据美国或别国的法案、法规和条约成为美国公民”[2]:79。

在判决公布前不久,大法官哈伦在对一组法律专业学生主持的讲座中表示,华人曾长期地被排除在美国社会以外,“这是一个我们完全一无所知,并且永远都不会相互融入的种族”。他还认为如果没有排华法案,大量的华人将在美国西部扎根。不过他也承认法庭的多数意见认为在美出生华人应该获得公民权,表示“当然,另一方的说法是宪法中对这种情况的出现坦然处之”[125]。

后续发展

当代反应

判决于1898年3月28日公布后不久,旧金山市检查官马歇尔·B·伍德沃斯在其分析文章中指出了对公民权条款管辖权的两种互不相让的理论,并总结指出“由于事实上法院对此案的裁决并非一致决定,因此这个议题至少是值得辩论的”[115]:556。不过他也认为最高法院的判决已经让这一争议告一段落,表示“很难看到会再有什么有效的反对意见提出来”[115]:561。发表在《耶鲁法律期刊》上的另一篇案件分析文章则支持了法院判决中的反对意见[116]。

1898年3月30日《旧金山纪事报》发表社论,表达了对两天前作出的黄金德案判决“可能对公民权问题产生更为广泛影响”的担忧,特别是这一判决可能不仅会让华人拥有公民权和投票权,日裔和美洲原住民也会拥有一样的权利。社论中建议“或者有必要……修改宪法来规定公民权只能赋予白人和黑人”[126]。

对黄金德家庭的影响

由于黄金德的美国公民身份得到了联邦最高法院的确认,他的长子于1910年从中国来到了美国,希望能够根据血统主义原则成为美国公民[66]。但美国移民局官员声称这与其在移民听证会上的证词不符,因而拒绝接受黄金德有关这个男孩是他儿子的说法[127]。黄金德的另外3个儿子于1924至1926年间先后来到美国,并且都成功成为了美国公民[68][128][129]。

黄金德案后的公民权法律

美国目前的法律规定,出生时自动获得公民权的途径有两种,一种是属地主义原则规定的在美国领地出生,另一种则是血统主义原则确立的从父母血缘关系上确立[5]。在黄金德案以前,联邦最高法院曾在艾尔克诉威尔金斯案中判决出生地原则不足以赋予美洲原住民美国公民权[130],但是,国会还是通过《1924年印第安人公民法》将公民权赋予了印第安人[131][132][133]。

一开始为限制华人移民归化而制订的《排华法案》最终被《1943年美国废除排华法》[134]和《1965年移民和国籍法案》[135][49]:63[136]取代。

黄金德案与之后的案件

自黄金德案判决多年后,以属地主义原则赋予公民权的概念“从来没有被最高法院严肃地质疑过,并且也由下级法院作为教条所接受”。自该案后,涉及公民权问题的案件主要都是考虑公民权条款中没有确立的情况[2]:80。如生活在国外美国公民后代的血统主义原则问题[137]或失去美国公民权的特殊情况[138]。

黄金德案确立的以属地主义原则作为确定美国公民身份首要规则的判决也已在多个有关美国出生的中国或日本血统后代公民权案件中得到援引[138][139][140][141]。而法院判决中认为宪法应该以英国普通法视角解读的意见也被多个涉及解读宪法或国会通过法案的最高法院案件所援引[142][143][144]。1982年的一个涉及非法移民权利的案件中也引用了法院在黄金德案中对第十四条修正案的解读[145]。

1942年的里根诉金案(Regan v. King)对2600名在美国出生日裔人士的公民权提出了挑战。原告律师称黄金德案是最高法院所做出过“最具伤害力也是最不幸的判决之一”,并称希望这个新的案件可以给法院“一个纠正自己的机会”[146]。联邦地区法院[147][148]和第九巡回上诉法院[149]都断然拒绝了这种论调,并援引黄金德案为一个有效的法律先例,最高法院也拒绝了这个案件的调卷令[150]。

黄金德案的判决还引来了一些美国占领或部分占领菲律宾期间(1898至1902年)在其占领地出生的人要求美国公民权,联邦上诉法院已经多次拒绝接受通过援引黄金德案来认同这些要求[151][152]。其中一个联邦上诉法院的裁决中还批评了黄金德案将属地主义原则与非法移民联系起来,不过与此同时法院也承认无法改变这一规则,因此敦促国会采取行动[153]。

黄金德案与非法移民的后代

从1990年代起,根据属地主义原则是否应该将美国公民身份自动赋予非法移民后代的问题开始出现[154][155],一些媒体记者和游说团体对这些问题提出了争议[156]。公众对其的辩论也引起了对黄金德案判决的重新审视[157]。

一些法律学者认为属地主义原则不适用于非法移民,黄金德案的先例也不适用于父母以非法方式居留在美国境内的情况。前查普曼大学法学院院长约翰·C·伊斯斯曼认为黄金德案并不能令非法移民后代自动获得公民权,因为在他看来,“受合众国管辖”要求全面和彻底的司法管辖,因此不适用于非法滞留的外国人[158]。他还进一步认为黄金德案判决在处理管辖权这一概念时有根本性的缺陷[159],判决后国会通过的《1924年印第安公民法》说明,如果国会也认为“公民权条款会赋予那些意外出生者公民权”,那么这一条法律根本就没有必要进行制订[160]。彼得·H·施努克和罗杰·M·史密斯对管辖权方面也有类似的看法[161]。据德克萨斯州大学奥斯汀分校法学教授莱诺·格拉格里亚所说,即使黄金德案解决了合法居民后代的(公民权)问题,但对那些非法居民仍然不适用[162]。美国联邦最七巡回上诉法院法官理查德·A·波斯纳也批评了将公民权赋予非法移民后代的做法,建议国会可以并且也应该采取行动来改变这一政策[153]。美国联邦参议院司法委员会移民问题小组前法律顾问查尔斯·伍德(Charles Wood)也反对这种做法,并曾在1999年呼吁尽可能快通过国会法案或是宪法修正案停止其继续执行[163]。

不过,巴尔的摩大学法学教授加瑞特·艾普斯对这样的观点表示反对。他认为“在‘美国诉黄金德案’中,联邦最高法院认为这种(出生公民权的)保证适用于所有外国人在美国领土上出生的后代,即使其父母不是美国公民并且也不符合成为美国公民的标准也不例外”[3]:332。他还进一步指出,“从实际来看,在美国出生的孩童不论其父母移民状态都可以成为美国公民”[3]:333。在艾普斯看来,第十四条修正案的制订者们“会毫不动摇地坚持公民权条款应该涵盖”那些不受欢迎移民和吉普赛人的后代,因此他认为黄金德案的判决在理解制宪意图上是“无懈可击”的[3]:381。

纽约大学法学院教授克丽斯蒂娜·罗德里格兹(Cristina Rodriguez)认为,黄金德当年的处境在“每一个有意义的方面都与”非法移民的后代相似,因为“他们都涉及移民父母还不符合政策中要成为公民的要求”。罗德里格兹声称黄金德案的判决是“对那些认为一个人的身份取决于其父母身份想法的强大反击”[164]:1367。针对史密斯和施努克的反对意见,罗德里格兹还说:“从所有实际目的上来看,这场辩论早就已经有了结论。虽然在过去几年中对移民政策的改革有了一些新的关注,并试图促使国会通过立法拒绝未经授权儿童的公民权。但是并没有人对此采取行动,这很大程度上是因为人们普遍认为最高法院会宣布这样的法律违宪”[164]:1363-1364。

詹姆斯·胡也表示了与罗德里格兹类似的看法,表示“第十四条修正案保证了出生公民权。这样的保护并不会因为孩子父母是坐‘五月花号’进入或是非法进入就有任何区别[165]。”他还认为那些声称公民权条款并没有意图要赋予外国人后代公民权的人都无视了1866年参议院针对在第十四条修正案中加上这一条款提议所进行的辩论[166]。

1982年,最高法院审理了普莱勒诉杜伊案[167],案件涉及在国外出生的孩子与父母一起非法进入美国后要求公民权的问题。法院认为第十四条修正案的管辖权同样适用于非法移民及其后代[168][169]。一项德克萨斯州州法曾试图拒绝非法移民的后代进入公立学校就读,州政府声称“非法进入美国的人即使居留在某州范围内且服从其法律也不属该州‘管辖范围’”[145]。最高法院对此以5比4作出的裁决指出,根据黄金德案,第十四条修正案中“并受其管辖”和“管辖范围内”实质上是同样的意思;两种表达都主要是指物理存在而非政治忠诚[103],因此黄金德案判决同样令非法移民的后代受益[168]。法院裁决认定,第十四条修正案的管辖权与一个人是否是以合法方式进入美国无关[145][170]。

虽然持不同意见的另外4位大法官不认同多数意见中有关这类儿童是否有权进入公立学校就读的问题,但他们仍然同意第十四条修正案管辖权适用于非法移民[171]。詹姆斯·胡认为这一个案件应该可以让那些对这一系列问题的疑虑和争论“平息下来”了[172]。

美国国务院(联邦政府中负责国际关系的部门,行使其他國家外交部的權力)认为在美国出生的非法移民后代受到美国的管辖,因而其一出生就拥有公民权。《美国国务院外交事务手册》所持立场认为这一问题已经由黄金德案判决所解决[154]。

根据露西·塞尔耶的说法,“黄金德案(确立)的出生公民权原则在一个多世纪的时间内仍然完好无损,在美国的原则和实践中仍然被基本认为是一个自然而完善的规则,已经不大可能会被彻底改变[40]:79。”

试图推翻黄金德案判决的立法

为了响应公众打击非法移民的要求[103],同时也担心非法移民的后代成为美国公民后,其相应本没有资格继续停留在国内的亲属也全部都成为“连锁移民”,国会曾数次提出法案试图挑战对公民权条款的常规解读,并寻求办法积极和明确地拒绝给予外国游客或非法居留人士在美国所生后代的公民权,但都没有成功[173]。2009年,来自乔治亚州的联邦众议员内森·迪尔在第111届国会上提出了《2009年出生公民权法》(Birthright Citizenship Act of 2009),这一法案就是旨在排除非法移民在美国所生子女对公民权条款的适用性[174];2011年1月5日,艾奥瓦州众议员史蒂夫·金又在第112届提出了与之类似的《2011年出生公民权法》(Birthright Citizenship Act of 2011)[175];2011年4月5日,来自路易斯安纳州的联邦参议员大卫·韦特也在参议院提出了类似的法案“S. 723”[176];不过截止2011年12月,《2011年出生公民权法》还没有进入众议院或参议院的议程。

由于有黄金德案的先例,所以国会通过的任何试图改变公民权条款解读的法案都很可能会被法院判决违宪[164]:1363-1364。因此也有人考虑通过宪法修正案来改写第十四条修正案中的字句,从而达到拒绝给予非法移民后代美国公民身份的目标。比如上面提到的路易斯安纳州参议员韦特就曾在第111届国会上提出了一个类似的联合决议案,但与几位众议员提交的法案一样,这一议案也没能在2010年12月22日国会休会前进入两院议程[177]。韦特又在2011年1月25日重新提出了这一个修正案提案,截止2011年12月,这一提案仍然没有能进入两院的议程[178]。

2010和2011年,亚历桑那州的州议员提出法案拒绝向父母无法证明自己是合法居留在美国境内人士的子女发放出生证明书。据报道,这类法案的支持者们希望可以令一个非法居留外国人所生子女出生公民权的案件到达联邦最高法院,进而有希望可以限制甚至推翻黄金德案的判决[179][180][181]。

注释

- ^ 1.0 1.1 United States v. Wong Kim Ark, 169 U.S. 649, 715 (1898).

- ^ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 Glen, Patrick J. Wong Kim Ark and Sentencia que Declara Constitucional la Ley General de Migración 285-04 in Comparative Perspective: Constitutional Interpretation, Jus Soli Principles, and Political Morality. University of Miami Inter-American Law Review. Fall 2007, 39 (1): 67–109. JSTOR 40176768.

- ^ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Epps, Garrett. The Citizenship Clause: A 'Legislative History' (pdf). American University Law Review. 2010, 60 (2): 329–388 [2013-12-09]. (原始内容存档于2013-01-12).

- ^ Woodworth, Marshall B. Citizenship of the United States under the Fourteenth Amendment. American Law Review (St. Louis: Review Pub. Company). 1896, 30: 535–555.

- ^ 5.0 5.1 "Acquisition of U.S. Citizenship by Birth in the United States", 7 FAM 1111(a).

- ^ Woodworth (1896), p. 538. "As a matter of fact, there was no definition in the constitution, or in any of the Acts of Congress, as to what constituted citizenship, until the enactment of the Civil Rights Bill in 1866, and the adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment in 1868."

- ^ Woodworth (1896), p. 538. "So generally accepted and acted upon has been the impression that birth in this country ipso facto confers citizenship, that there are, to-day, thousands of persons born in the United States of foreign parents, who consider themselves, and are recognized, legally, as citizens. Among these are very many voters, whose right to vote, because born here of foreign parents, has never been seriously questioned."

- ^ "Authorities", 7 FAM 1119(d). "Until 1866, the citizenship status of persons born in the United States was not defined in the Constitution or in any federal statute. Under the common law rule of jus soli—the law of the soil—persons born in the United States generally acquired U.S. citizenship at birth."

- ^ Woodworth (1896), p. 537. "[T]he commonly accepted notion in this country, both prior and subsequent to the adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment ... has been that birth within the United States, although of alien parents, was sufficient, of itself, to confer the right of citizenship, without any other requisite, such for instance, as the naturalization proceedings which take place with reference to aliens."

- ^ Walter Dellinger, Assistant Attorney General. Legislation denying citizenship at birth to certain children born in the United States. Memoranda and Opinions. Office of Legal Counsel, U.S. Department of Justice. 1995-12-13 [2013-12-09]. (原始内容存档于2013-12-22).

A bill that would deny citizenship to children born in the United States to certain classes of alien parents is unconstitutional on its face. A constitutional amendment to restrict birthright citizenship, although not technically unlawful, would flatly contradict the Nation's constitutional history and constitutional traditions.

- ^ Lynch v. Clarke, 3 N.Y.Leg.Obs. 236 (N.Y. 1844).

- ^ Lynch v. Clarke, 3 N.Y.Leg.Obs. at 250. "Upon principle, therefore, I can entertain no doubt, but that by the law of the United States, every person born within the dominions and allegiance of the United States, whatever were the situation of his parents, is a natural born citizen.... I am bound to say that the general understanding ... is that birth in this country does of itself constitute citizenship.... Thus when at an election, the inquiry is made whether a person offering to vote is a citizen or an alien, if he answers that he is a native of this country, it is received as conclusive that he is a citizen.... The universality of the public sentiment in this instance ... indicates the strength and depth of the common law principle, and confirms the position that the adoption of the Federal Constitution wrought no change in that principle."

- ^ 13.0 13.1 An Act to establish an [sic] uniform Rule of Naturalization 1st Cong., Sess. II, Chap. 3; 1 Stat. 103. 1790-3-26. The Library of Congress. [2013-12-09].

Be it enacted ... That any alien, being a free white person, who shall have resided within the limits and under the jurisdiction of the United States for the term of two years, may be admitted to become a citizen thereof.... And the children of citizens of the United States, that may be born beyond sea, or out of the limits of the United States, shall be considered as natural born citizens: Provided, That the right of citizenship shall not descend to persons whose fathers have never been resident in the United States....

- ^ Dred Scott v. Sandford, 60 U.S. 393 (1857).

- ^ Schwarz, Frederic D. The Dred Scott Decision. American Heritage (Rockville, MD: American Heritage Publishing). 2007-02-03, 58 (1) [2012-06-14]. (原始内容存档于2012-06-14).

- ^ An Act to protect all Persons in the United States in their Civil Rights, and furnish the Means of their Vindication. Milestone Documents. 39th Cong., Sess. I, Chap. 31; 14 Stat. 27. April 9, 1866. [2013-12-09]. (原始内容存档于2013-12-03).

- ^ "Authorities", 7 FAM 1119(e). "This rule was made part of the Civil Rights Act of April 9, 1866 (14 Statutes at Large 27)...."

- ^ Civil Rights Act of 1866. The Online Library of Liberty. [2013-12-09]. (原始内容存档于2013-05-20).

- ^ Wong Kim Ark, 169 U.S. at 675. "The same Congress, shortly afterwards, evidently thinking it unwise, and perhaps unsafe, to leave so important a declaration of rights to depend upon an ordinary act of legislation, which might be repealed by any subsequent Congress, framed the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution...."

- ^ Epps, Garrett. Democracy Reborn: The Fourteenth Amendment and the Fight for Equal Rights in Post-Civil War America. Holt Paperbacks. 2007: 174. ISBN 978-0-8050-8663-8.

The opposition made several arguments. The citizenship provision was unconstitutional, they contended, and would grant citizenship, not only to freed slaves, but to Indians living off their reservations, to Chinese born in the United States, and even to gypsies. [Illinois Senator Lyman] Trumbull agreed that it would, opening a chorus of cries that the bill would cede California to China and make America a mongrel nation.

- ^ The Congressional Globe 39th Cong., 1st Sess. 597. 1866-02-02 [2013-12-09].

Congress has no power to make a citizen.... [only] to establish a uniform rule of naturalization.

- ^ Law Library of Congress: Fourteenth Amendment and Citizenship. Library of Congress. [2013-12-09]. (原始内容存档于2013-03-03).

However, because there were concerns that the Civil Rights Act might be subsequently repealed or limited the Congress took steps to include similar language when it considered the draft of the Fourteenth Amendment.

- ^ 任东来; 陈伟; 白雪峰; Charles J. McClain; Laurene Wu McClain. 美国宪政历程:影响美国的25个司法大案. 中国法制出版社. 2004年1月: 574. ISBN 7-80182-138-6.

- ^ 李道揆. 美国政府和政治(下册). 商务印书馆. 1999: 775–799.

- ^ Stimson, Frederic Jesup. The Law of the Federal and State Constitutions of the United States. Clark, NJ: The Lawbook Exchange. 2004: 76. ISBN 978-1-58477-369-6.

- ^ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. 2890 (1866-5-30).

- ^ Law Library of Congress: Fourteenth Amendment and Citizenship. Library of Congress. [2013-12-09]. (原始内容存档于2013-03-03).

The debate in the Senate was conducted in a somewhat acrimonious fashion and focused in part on the difference between the language in the definition of citizenship in the Civil Rights Act of 1866 and the proposed amendment. Specific discussion reviewed the need to address the problem created by the Dred Scott decision, but also the possibility that the language of the Howard amendment would apply in a broader fashion to almost all children born in the United States. The specific meaning of the language of the clause was not immediately obvious.

- ^ Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. 2890 (1866-5-30). "I am really desirous to have a legal definition of 'Citizenship of the United States.' What does it mean? What is its length and breadth? ... Is the child of the Chinese immigrant in California a citizen? Is the child of a Gypsy born in Pennsylvania a citizen? ... Why, sir, there are nations of people with whom theft is a virtue and falsehood a merit.... It is utterly and totally impossible to mingle all the various families of men, from the lowest form of the Hottentot up to the highest Caucasian, in the same society.... and in my judgment there should be some limitation, some definition to this term 'citizen of the United States.'"

- ^ Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. 2891 (1866-5-30).

- ^ Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. 2892 (1866-5-30). "And yet by a constitutional amendment you propose to declare the Utes, the Tabahuaches, and all those wild Indians to be citizens of the United States, the great Republic of the world, whose citizenship should be a title as proud as that of king, and whose danger is that you may degrade that citizenship."

- ^ Ho (2006), p. 372. "But although there was virtual consensus that birthright citizenship should not be extended to the children of Indian tribal members, a majority of Senators saw no need for clarification."

- ^ Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. 2897 (1866-5-30).

- ^ Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. 3149 (1866-6-13).

- ^ Proclamation by William H. Seward, Secretary of State. The Library of Congress. 1868-07-28 [2013-12-09].

- ^ Liu, Goodwin. Education, Equality, and National Citizenship (PDF). Yale Law Journal. 2006, 116: 349 [2013-12-09]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2011-07-06).

- ^ Elizabeth B. Wydra. Huffington Post. [2013-12-09]. (原始内容存档于2013-03-27).

- ^ Wydra, Elizabeth. Birthright Citizenship: A Constitutional Guarantee (PDF). American Constitution Society for Law and Policy: 6. 2009 [2013-12-09]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2013-07-30).

For example, Senator Cowan expressed concern that the proposal would expand the number (原文如此) Chinese in California and Gypsies in his home state of Pennsylvania by granting birthright citizenship to their children, even (as he put it) the children of those who owe no allegiance to the United States and routinely commit 'trespass' within the United States. Supporters of Howard's proposal did not respond by taking issue with Cowan's understanding, but instead by agreeing with it and defending it as a matter of sound policy.

- ^ Ho (2006), p. 370. "[Senator Howard's] understanding was universally adopted by other Senators. Howard's colleagues vigorously debated the wisdom of his amendment—indeed, some opposed it precisely because they opposed extending birthright citizenship to the children of aliens of different races. But no Senator disputed the meaning of the amendment with respect to alien children."

- ^ Aynes, Richard L. Unintended consequences of the Fourteenth Amendment and what they tell us about its interpretation. Akron Law Review. 2006, 39: 289 [2013-12-09].[永久失效連結]

- ^ 40.0 40.1 40.2 40.3 40.4 40.5 40.6 Salyer, Lucy E. Wong Kim Ark: The Contest Over Birthright Citizenship. Martin, David; Schuck, Peter (编). Immigration Stories. New York: Foundation Press. 2005. ISBN 1-58778-873-X.

- ^ Burlingame Treaty, 16 Stat. 739. 1868-7-28.

- ^ English and Chinese Text of the Burlingame Treaty 1868. [2013-12-09].

- ^ Meyler, Bernadette. The Gestation of Birthright Citizenship, 1868–1898 States' Rights, the Law of Nations, and Mutual Consent. Georgetown Immigration Law Journal. Spring 2001, 15: 521–525.

- ^ Aarim-Heriot, Najia. Chinese Immigrants, African Americans, and Racial Anxiety in the United States, 1848–82. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press. : 108–112. ISBN 0-252-02775-2.

- ^ An act to execute certain treaty stipulations relating to Chinese. 47th Cong., Sess. I, Chap. 126; 22 Stat. 58. 1882-5-6.

- ^ Dake, B. Frank. The Chinaman before the Supreme Court. Albany Law Journal. 1905-9, 67 (9): 259–260.

- ^ An act a supplement to an act entitled "An act to execute certain treaty stipulations relating to Chinese". 50th Cong., Sess. I, Chap. 60; 25 Stat. 504. 1888-10-1.

- ^ An act to prohibit the coming of Chinese persons into the United States. 52nd Cong., Sess. I, Chap. 60; 27 Stat. 25. 1892-5-5.

- ^ 49.0 49.1 49.2 49.3 Elinson, Elaine; Yogi, Stan. Wherever There's a Fight: How Runaway Slaves, Suffragists, Immigrants, Strikers and Poets Shaped Civil Liberties in California. Berkeley, CA: Heyday Books. 2009. ISBN 978-1-59714-114-7.

- ^ Chinese Exclusion Act (1882). Our Documents. [2013-12-09]. (原始内容存档于2013-10-29).

- ^ Woodworth (1896), p. 538. "It is significant that since the adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment, the question has arisen simply with reference to Chinese and Indians."

- ^ "Native Americans and Eskimos", 7 FAM 1117(a). "Before U.S. v. Wong Kim Ark, the only occasion on which the Supreme Court had considered the meaning of the 14th Amendment's phrase 'subject to the jurisdiction' of the United States was in Elk v. Wilkins, 112 U.S. 94 (1884)."

- ^ 53.0 53.1 Elk v. Wilkins, 112 U.S. 94 (1884).

- ^ Urofsky, Melvin I.; Finkelman, Paul. A March of Liberty: A Constitutional History of the United States 1 2nd. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. 2002 [2013-09-04]. ISBN 0-19-512635-1.

- ^ 55.0 55.1 In re Look Tin Sing, 21 F. 905 (D.Cal. 1884). Thayer, James Bradley. Cases on constitutional law, with notes (Part 2). Charles W. Sever. 1894: 578–582 [2012-01-02].

- ^ 56.0 56.1 麥禮謙數碼檔案 English/Chinese Glossary of Biographical and Institutional Names (Excel) https://himmarklai.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/Biographical-Institutional-Glossary.xls

- ^ University of New Hampshire – History Department – Faculty Profiles. [2013-06-22]. (原始内容存档于2013-06-22).

- ^ Lee, Erika. At America's gates: Chinese immigration during the exclusion era, 1882–1943. University of North Carolina Press. 2003: 103 [2012-01-02]. ISBN 978-0-8078-5448-8.

- ^ Gee Fook Sing v. U.S., 49 F. 146 (9th Cir. 1892).

- ^ Slaughter-House Cases, 83 U.S. 36 (1873).

- ^ 61.0 61.1 Woodworth (1896), p. 537. "On the other hand, the Supreme Court, in the Slaughter-house cases, used language which indicates that it then considered the provision as declaratory of the doctrine of the law of nations."

- ^ 62.0 62.1 62.2 Woodworth (1896), p. 538. "The Supreme Court, singular to say, has never directly passed on the political status of children born in this country of foreign parents. The question was not directly involved in the Slaughter-house cases, and what the court there stated is, therefore, dictum, and was so treated by Judge Morrow in the Wong Kim Ark case."

- ^ 63.0 63.1 Semonche (1978), p. 112. "Gray then sidestepped language in earlier opinions of the Court that said children born of alien parents are not citizens by saying, in effect, that such conclusions were gratuitous statements not necessary to the decisions in those cases and therefore entitled to no weight as precedent."

- ^ 转写自台山話发音:wong11 gim33 'ak3.

- ^ Wong Kim Ark, 169 U.S. at 649. "This was a writ of habeas corpus ... in behalf of Wong Kim Ark, who alleged that he ... was born at San Francisco in 1873 ...."

- ^ 66.0 66.1 First page of testimony given by Wong Kim Ark at an immigration hearing for his eldest son, Wong Yoke Fun, on 1910-12-6. U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, San Bruno, California. (Wong Kim Ark gives his birthdate as "T. C. 10, 9th month, 7th day"—a Chinese imperial calendar date said in the transcript of the testimony to correspond to October 20, 1871.)

- ^ Affidavit signed by Wong Kim Ark on November 5, 1894. U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, San Bruno, California. (Wong gives his age as 23.)

- ^ 68.0 68.1 First page of testimony given by Wong Kim Ark at an immigration hearing for his third son, Wong Yook Thue, on 1925-3-20. U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, San Bruno, California. (Wong Kim Ark gives his age as 56. The immigration board also acknowledges the presence at the hearing of Wong Yook Thue's "prior landed alleged brother Wong Yook Sue".)

- ^ First page of testimony given by Wong Kim Ark at an immigration hearing for his youngest son, Wong Yook Jim, on July 23, 1926. U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, San Bruno, California. (Wong Kim Ark gives his age as 57.)

- ^ Davis, Lisa. The Progeny of Citizen Wong. SF Weekly. 1998-11-04 [2013-12-09]. (原始内容存档于2013-05-21).

Wong Kim Ark spent most of his life as a cook in various Chinatown restaurants. In 1894, Wong visited his family in China.

- ^ 71.0 71.1 Wong Kim Ark, 169 U.S. at 650. "Because the said Wong Kim Ark, although born in the city and county of San Francisco, State of California, United States of America, is not, under the laws of the State of California and of the United States, a citizen thereof, the mother and father of the said Wong Kim Ark being Chinese persons and subjects of the Emperor of China, and the said Wong Kim Ark being also a Chinese person and a subject of the Emperor of China."

- ^ Collins, George D. Citizenship by Birth. American Law Review. 1895-05-06, 29: 385–394.

...[W]ere it not for the fact that the executive department of the general government has apparently acquiesced in Judge Field's [Look Tin Sing] decision as a correct interpretation of the law, we might well be indifferent to what he did or did not decide in the particular case before the Circuit Court, knowing as we do that when the question is ultimately brought before the Supreme Court of the United States, Judge Field's views will not be sustained.

- ^ Woodworth (1898), p. 556. "From this refusal to permit him to land, a writ of habeas corpus was sued out in the United States District Court .... [T]hat court discharged Wong Kim Ark on the ground that he was a citizen of the United States by virtue of his birth in this country, and that the Chinese Exclusion Acts were therefore inapplicable to him."

- ^ In re Wong Kim Ark, 71 F. 382 (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) 互联网档案馆的存檔,存档日期2010-05-13. (N.D.Cal. 1896).

- ^ Woodworth (1896), p. 536. "In the United States, the [citizenship] question must depend upon the interpretation to be given to the first clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution, but the peculiar language of a phrase in that provision renders it a somewhat debatable point as to whether the provision was intended to be declaratory of the common law or of the international doctrine."

- ^ Woodworth (1898), p. 555. "While the question before the Supreme Court was, what constitutes citizenship of the United States under the Fourteenth Amendment, still the peculiar phraseology of the citizenship clause of that Amendment necessarily involved the further and controlling proposition as to what that clause was declaratory of; whether it was intended to be declaratory of the common-law or of the international doctrine."

- ^ In re Wong Kim Ark, 71 F. at 386.

- ^ Rodriguez (2009), pp. 1364–1366. "[W]hat weight do we assign the Supreme Court's first attempts to interpret the [Citizenship Clause] after its passage (the extension of the Citizenship clause to children of immigrants not eligible for citizenship in Wong Kim Ark)? ... and ambiguity as to whether the Clause extended to the children of Chinese immigrants persisted until the Supreme Court interpreted the Clause in Wong Kim Ark."

- ^ Slaughter-House Cases, 83 U.S. 36 (1873)

- ^ In re Wong Kim Ark, 71 F. at 391. "That this last sentence, which is the expression relied on by counsel for the government, is mere dictum, is plain from what has been stated as the issue involved in those cases."

- ^ Woodworth (1896), p. 537. "The rule laid down by the Supreme Court in Elk v. Wilkins, with respect to the political status of Indians is, however, not applicable to that of Chinese, or persons other than Chinese, born here of foreign parents."

- ^ In re Wong Kim Ark, 71 F. at 391. "Nor does the interpretation of the phrase in question in the case of Elk v. Wilkins ... dispose of the matter."

- ^ Woodworth (1896), p. 537. "The decisions, which have passed upon the political status of Chinese born here, were all rendered in the Ninth Circuit, and they hold that the Fourteenth Amendment was intended to be declaratory of the common-law rule, and that birth in this country is sufficient to confer the right of citizenship."

- ^ In re Wong Kim Ark, 71 F. at 391. "That being so, the observations referred to and relied upon, however persuasive they may appear to be, cannot be accepted as declaring the law in this circuit, at least as against the authority of In re Look Tin Sing, where the question was squarely met and decisively settled."

- ^ Slaughterhouse Cases, 83 U.S. at 74.

- ^ The native-born Chinese are legally adjudged to be citizens. San Francisco Chronicle. 1896-01-04: 12.

Judge Morrow decided yesterday that a Chinese, though a laborer, if born in this country, is a citizen of the United States, and as such cannot lose his right to land here again after leaving the country.

- ^ Order of the District Court of the United States, Northern District of California, "In the Matter of Wong Kim Ark", 1896-1-3, U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved 2011-7-17.

- ^ Woodworth (1898), p. 556. "Upon a hearing duly had, that [district] court discharged Wong Kim Ark on the ground that he was a citizen of the United States by virtue of his birth in this country, and that the Chinese Exclusion Acts were therefore inapplicable to him."

- ^ In re Wong Kim Ark, 71 F. at 392. "Arriving at the conclusion, as I do, after careful investigation and much consideration, that the supreme court has as yet announced no doctrine at variance with that contained in the Look Tin Sing decision and the other cases alluded to, I am constrained to follow the authority and law enunciated in this circuit.... The doctrine of the law of nations, that the child follows the nationality of the parents, and that citizenship does not depend upon mere accidental place of birth, is undoubtedly more logical, reasonable, and satisfactory, but this consideration will not justify this court in declaring it to be the law against controlling judicial authority.... From the law as announced and the facts as stipulated, I am of opinion (原文如此) that Wong Kim Ark is a citizen of the United States within the meaning of the citizenship clause of the fourteenth amendment."

- ^ Woodworth (1896), p. 554. "I understand that the Wong Kim Ark case will be appealed to the Supreme Court, and, therefore, this at once delicate and important question will receive the consideration of that able tribunal, and the subject be set at rest so far as the existing law is concerned."

- ^ Wong Kim Ark, 169 U.S. at 652. "The [district] court ordered Wong Kim Ark to be discharged, upon the ground that he was a citizen of the United States. The United States appealed to this court...."

- ^ Semonche, John E. Charting the Future: The Supreme Court Responds to a Changing Society, 1890–1920. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. 1978: 111. ISBN 0-313-20314-8. LCCN 77-94745.

- ^ Wong Kim Ark, 169 U.S. at 652 (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆).

- ^ Ashton, J. Hubley. Lincolniana: A Glimpse of Lincoln in 1864. Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society. 1976-2, 69 (1): 67–69.

The reminiscence printed below was written by J. Hubley Ashton, assistant attorney general of the United States from 1864 to 1869.

- ^ Biographies: Thomas D. Riordan. Federal Judicial Center. [2012-01-17].

- ^ Wong Kim Ark, 169 U.S. at 653.

- ^ Semonche (1978), p. 111. "Since [Associate Justice Joseph] McKenna did not hear the oral arguments, he did not participate in the decision."

- ^ Wong Kim Ark, 169 U.S. at 732. "MR. JUSTICE McKENNA, not having been a member of the court when this case was argued, took no part in the decision."

- ^ American Society of International Law. Judicial Decisions Involving Questions of International Law. American Journal of International Law (New York: Baker, Voorhis & Co.). 1914, 8: 672.

- ^ Wong Kim Ark Is a Citizen: Supreme Court Decision in Case of Chinese Born in America. Washington Post. 1898-03-29: 11.

- ^ Woodworth (1898), p. 556. "Mr. Justice Gray wrote the prevailing opinion, which was concurred in by all the justices excepting Mr. Chief Justice Fuller and Mr. Justice Harlan, both of whom dissented. Mr. Justice McKenna, not having been a member of the court when the arguments took place, did not participate in the decision."

- ^ Wong Kim Ark, 169 U.S. at 654.

- ^ 103.0 103.1 103.2 Kirkland, Brooke. Limiting the Application of Jus Soli: The Resulting Status of Undocumented Children in the United States. Buffalo Human Rights Law Review. 2006, 12: 200.

- ^ Woodworth (1898), p. 559. "In arriving at the conclusion that Wong Kim Ark was a citizen of the United States, although born in this country of foreign parents, the court uses the following language...."

- ^ Bouvier, John. Citizen. Bouvier's Law Dictionary and Concise Encyclopedia 1. Kansas City, MO: Vernon Law Book Company: 490. 1914.

- ^ Wong Kim Ark, 169 U.S. at 681.

- ^ Martin, David; Schuck, Peter. Immigration Stories. New York: Foundation Press. 2005: 75. ISBN 978-1-58778-873-4.

In its analysis of the nature of national jurisdiction, the Court relied heavily on Chief Justice John Marshall's broad statement....

- ^ The Schooner Exchange v. M'Faddon, 11 U.S. (7 Cranch) 116, 136 (1812).

- ^ Wong Kim Ark, 169 U.S. at 683.

- ^ Woodworth (1898), p. 559. "The refusal of Congress to permit the naturalization of Chinese persons cannot exclude Chinese persons born in this country from the operation of the constitutional declaration that all persons born in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States."

- ^ Wong Kim Ark, 169 U.S. at 699.

- ^ Bouvier, John. Chinese. Bouvier's Law Dictionary and Concise Encyclopedia 1. Kansas City, MO: Vernon Law Book Co.: 482. 1914.

- ^ Marshal (原文如此) B. Woodworth Inducted into Office. San Francisco Chronicle. 1901-03-20: 14.

Marshall B. Woodworth, who was recently appointed United States Attorney for the Northern district of California ... took the oath of office yesterday before Judge Morrow in the United States Circuit Court.

- ^ Marshall B. Woodworth Killed. New York Times. 1943-04-19: 21.

Marshall B. Woodworth, 66, former United States attorney in San Francisco, was struck and killed by an automobile yesterday.

- ^ 115.0 115.1 115.2 115.3 Woodworth, Marshall B. Who Are Citizens of the United States? Wong Kim Ark Case. American Law Review (St. Louis: Review Pub. Company). 1898, 32: 554–561.

- ^ 116.0 116.1 Yale Law Journal. Jetsam and Flotsam: Citizenship of Chinaman Born in United States. Central Law Journal (St. Louis: Central Law Journal Company). 1898, 46: 519.

Although hopelessly in the minority, Chief Justice Fuller, with whom Mr. Justice Harlan agrees, dissents from this opinion, and, upon what appears to be the better view, holds that the common law of England does not control the question under discussion.

- ^ Wong Kim Ark, 169 U.S. at 713.

- ^ Wong Kim Ark, 169 U.S. at 709. "The framers of the Constitution were familiar with the distinctions between the Roman law and the feudal law, between obligations based on territoriality and those based on the personal and invisible character of origin, and there is nothing to show that, in the matter of nationality, they intended to adhere to principles derived from regal government, which they had just assisted in overthrowing. Manifestly, when the sovereignty of the Crown was thrown off and an independent government established, every rule of the common law and every statute of England obtaining in the Colonies in derogation of the principles on which the new government was founded was abrogated."

- ^ 119.0 119.1 Wong Kim Ark, 169 U.S. at 731.

- ^ The question of whether the Constitution could override a treaty remained unresolved until a 1957 Supreme Court case, Reid v. Covert, 354 U.S. 1 (1957).

- ^ Eastman (2006), p. 2. "The positively phrased 'subject to the jurisdiction' of the United States might easily have been intended to describe a broader grant of citizenship than the negatively phrased language from the 1866 Act.... But the relatively sparse debate we have regarding this provision of the Fourteenth Amendment does not support such a reading."

- ^ Wong Kim Ark, 169 U.S. at 721.

- ^ Wong Kim Ark, 169 U.S. at 725 n.2.

- ^ Wong Kim Ark, 169 U.S. at 726.

- ^ Przybyszewski, Linda. The Republic According to John Marshall Harlan. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. 1999: 120–121. ISBN 0-8078-2493-3.

- ^ Questions of Citizenship. San Francisco Chronicle. 1898-03-30: 6.

- ^ "Findings and Decree" denying Wong Yoke Fun's application for admission to the United States. 1910-12-27. U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, San Bruno, California.

- ^ Last page of the transcript of Wong Yook Thue's immigration hearing, showing that he is being admitted to the United States. 1925-3-20. U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, San Bruno, California. (This page also mentions that "another alleged son Wong Yook Seu (原文如此)" was refused admission to the U.S. in 1924, but was "subsequently landed by the Department on appeal".)

- ^ Last page of the transcript of Wong Yook Jim's immigration hearing, showing that he is being admitted to the United States. 1926-7-23. U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, San Bruno, California.

- ^ Wadley, James B. Indian Citizenship and the Privileges and Immunities Clauses of the United States Constitution: An Alternative to the Problems of the Full Faith and Credit and Comity?. Southern Illinois University Law Journal. Fall 2006, 31: 47.

- ^ An Act to authorize the Secretary of the Interior to issue certificates of citizenship to Indians. (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) Pub.L. 68–175; 43 Stat. 253. June 2, 1924.

- ^ Haas, Theodore. The Legal Aspects of Indian Affairs from 1887 to 1957. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications). 1957-5, 311: 12–22. JSTOR 1032349. doi:10.1177/000271625731100103.

- ^ "Native Americans and Eskimos", 7 FAM 1117(b). "The Act of June 2, 1924 was the first comprehensive law relating to the citizenship of Native Americans."

- ^ An Act to repeal the Chinese Exclusion Acts, to establish quotas, and for other purposes. (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) Pub.L. 78–199; 57 Stat. 600. 1943-12-17.

- ^ An Act to amend the Immigration and Nationality Act, and for other purposes. (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) Pub.L. 89–236; 79 Stat. 911. 1965-10-3.

- ^ Low, Elaine. An Unnoticed Struggle: A Concise History of Asian American Civil Rights Issues (PDF). San Francisco: Japanese American Citizens League: 4. 2008 [2012-01-27]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2010-06-13).

- ^ See, e.g., Rogers v. Bellei, 401 U.S. 815, 828 (1971). "The [Wong Kim Ark] Court concluded that 'naturalization by descent' was not a common law concept, but was dependent, instead, upon statutory enactment."

- ^ 138.0 138.1 See, e.g., Nishikawa v. Dulles, 356 U.S. 129, 138 (1958). "Nishikawa was born in this country while subject to its jurisdiction; therefore, American citizenship is his constitutional birthright. See United States v. Wong Kim Ark.... What the Constitution has conferred, neither the Congress, nor the Executive, nor the Judiciary, nor all three in concert, may strip away."

- ^ Kwock Jan Fat v. White, 253 U.S. 454, 457 (1920). "It is not disputed that if petitioner is the son of [his alleged parents], he was born to them when they were permanently domiciled in the United States, is a citizen thereof, and is entitled to admission to the country. United States v. Wong Kim Ark...."

- ^ Weedin v. Chin Bow, 274 U.S. 657, 660 (1927). "United States v. Wong Kim Ark ... establishes that, at common law in England and the United States, the rule with respect to nationality was that of the jus soli...."

- ^ Morrison v. California, 291 U.S. 82, 85 (1934). "A person of the Japanese race is a citizen of the United States if he was born within the United States. United States v. Wong Kim Ark...."

- ^ Hennessy v. Richardson Drug Co., 189 U.S. 25, 34 (1903). "United States v. Wong Kim Ark ... said: 'The term "citizen", as understood in our law, is precisely analogous to the term "subject" in the common law...."

- ^ Schick v. United States, 195 U.S. 65, 69 (1904). "In United States v. Wong Kim Ark ...: 'In this as in other respects, [a constitutional provision] must be interpreted in the light of the common law, the principles and history of which were familiarly known to the framers of the Constitution....'"

- ^ Kennedy v. Mendoza-Martinez, 372 U.S. 144, 159 n.10 (1963). "[The Citizenship Clause] is to be interpreted in light of preexisting common law principles governing citizenship. United States v. Wong Kim Ark...."

- ^ 145.0 145.1 145.2 Plyler v. Doe, 457 U.S. 202, 211 n.10 (1982). "Justice Gray, writing for the Court in United States v. Wong Kim Ark ... detailed at some length the history of the Citizenship Clause, and the predominantly geographic sense in which the term 'jurisdiction' was used. He further noted that it was 'impossible to construe the words "subject to the jurisdiction thereof" ... as less comprehensive than the words "within its jurisdiction" ... or to hold that persons "within the jurisdiction" of one of the States of the Union are not "subject to the jurisdiction of the United States."' ... As one early commentator noted, given the historical emphasis on geographic territoriality, bounded only, if at all, by principles of sovereignty and allegiance, no plausible distinction with respect to Fourteenth Amendment 'jurisdiction' can be drawn between resident aliens whose entry into the United States was lawful, and resident aliens whose entry was unlawful."

- ^ Asks U.S. Japanese Lose Citizenship. New York Times. 1942-06-27: 6.

- ^ Japanese Citizens Win a Court Fight. New York Times. 1942-07-03: 7.

- ^ Regan v. King, 49 F. Supp. 222 (N.D.Cal. 1942). "It is unnecessary to discuss the arguments of counsel. In my opinion the law is settled by the decisions of the Supreme Court just alluded to, and the action will be dismissed, with costs to the defendant."

- ^ Regan v. King, 134 F.2d 413 (9th Cir. 1943). "On the authority of the fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution, making all persons born in the United States citizens thereof, as interpreted by the Supreme Court of the United States in United States v. Wong Kim Ark, ... and a long line of decisions, including the recent decision in Perkins, Secretary of Labor et al. v. Elg, ... the judgment of dismissal, 49 F.Supp. 222, is Affirmed."

- ^ Regan v. King, cert. denied, 319 U.S. 753 (1943).

- ^ Nolos v. Holder, 611 F.3d 279, 284 (5th Cir. 2010). "Nolos urges that his parents acquired United States citizenship at birth because the Philippines were under the dominion and control of the United States at the time of their births. But as have the Ninth and the Second Circuits before us ... we decline to give Wong Kim Ark such an expansive interpretation. As the Second Circuit explained, the question of the territorial scope of the Citizenship Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment was not before the court in Wong Kim Ark." See also Rabang v. INS, 35 F.3d 1449, 1454 (9th Cir. 1994), and Valmonte v. INS, 136 F.3d 914, 920 (2nd Cir. 1998).

- ^ Halagao, Avelino J. Citizens Denied: A Critical Examination of the Rabang Decision Rejecting United States Citizenship Claims by Persons Born in the Philippines During the Territorial Period. UCLA Asian Pacific American Law Journal. 1998, 5: 77.

- ^ 153.0 153.1 Oforji v. Ashcroft, 354 F.3d 609 (7th Cir. 2003). "[O]ne rule that Congress should rethink ... is awarding citizenship to everyone born in the United States (... United States v. Wong Kim Ark ...), including the children of illegal immigrants whose sole motive in immigrating was to confer U.S. citzienship on their as yet unborn children.... We should not be encouraging foreigners to come to the United States solely to enable them to confer U.S. citizenship on their future children.... A constitutional amendment may be required to change the rule ... but I doubt it.... Congress would not be flouting the Constitution if it amended the Immigration and Nationality Act to put an end to the nonsense.... Our [judges'] hands, however, are tied. We cannot amend the statutory provisions on citizenship and asylum."

- ^ 154.0 154.1 "'Subject to the Jurisdiction of the United States'", 7 FAM 1111(d). "All children born in and subject, at the time of birth, to the jurisdiction of the United States acquire U.S. citizenship at birth even if their parents were in the United States illegally at the time of birth. ... Pursuant to [Wong Kim Ark]: (a) Acquisition of U.S. citizenship generally is not affected by the fact that the parents may be in the United States temporarily or illegally; and that (b) A child born in an immigration detention center physically located in the United States is considered to have been born in the United States and be subject to its jurisdiction. This is so even if the child's parents have not been legally admitted to the United States and, for immigration purposes, may be viewed as not being in the United States."

- ^ Ho (2006), p. 366. "There is increasing interest in repealing birthright citizenship for the children of aliens—especially undocumented persons."

- ^ 'Border Baby' boom strains S. Texas. Houston Chronicle. 2006-09-24 [2011-07-17].

Immigration-control advocates regard the U.S.-born infants as 'anchor babies' because they give their undocumented parents and relatives a way to petition for citizenship.

- ^ Wong, William. The citizenship of Wong Kim Ark. San Francisco Examiner. 1998-04-08 [2011-09-10].

- ^ Eastman (2006), pp. 3–4. "Such was the interpretation of the Citizenship Clause initially given by the Supreme Court, and it was the correct interpretation. As Thomas Cooley noted in his treatise, 'subject to the jurisdiction' of the United States 'meant full and complete jurisdiction to which citizens are generally subject, and not any qualified and partial jurisdiction, such as may consist with allegiance to some other government.'"

- ^ Eastman (2006), p. 4. "Justice Gray simply failed to appreciate what he seemed to have understood in Elk [v. Wilkins], namely, that there is a difference between territorial jurisdiction, on the one hand, and the more complete, allegiance-obliging jurisdiction that the Fourteenth Amendment codified, on the other."

- ^ Eastman (2006), p. 6. "Indeed, Congress has by its own actions with respect to Native Americans—both before and after this Court's decision in Wong Kim Ark—rejected the claim that the Citizenship Clause itself confers citizenship merely by accident of birth. None of these citizenship acts would have been necessary—indeed, all would have been redundant—under the expansive view of the Citizenship Clause propounded by Justice Gray."

- ^ Indians and Invaders: The Citizenship Clause and Illegal Aliens (PDF). University of Pennsylvania Journal of Constitutional Law (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania). 2008-3, 10 (3): 509 [2011-07-17]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2011-06-16).

The Court has not revisited Wong Kim Ark, but Schuck and Smith offer a reading of the Citizenship Clause that connects the exclusions to birthright citizenship with a principle of reciprocal consent or allegiance.

- ^ Graglia, Lino. Birthright citizenship for children of illegal aliens: an irrational public policy. Texas Review of Law and Politics (Austin, TX: University of Texas, Austin). 2009, 14 (1): 10.

- ^ Wood, Charles. Losing Control of America's Future—The Census, Birthright Citizenship, and Illegal Aliens. Harvard Journal of Law and Public Policy. 1999, 22: 465.

The needed reforms should be completed expeditiously.... [I]n every week that passes thousands more children of illegal aliens are born in this country, and each is now granted citizenship.... If these reforms are not accomplished one way or another soon, 'We the People of the United States' risk losing control of the nation's future.

- ^ 164.0 164.1 164.2 Rodriguez, Cristina M. The Second Founding: The Citizenship Clause, Original Meaning, and the Egalitarian Unity of the Fourteenth Amendment. University of Pennsylvania Journal of Constitutional Law. 2009, 11.

- ^ Ho, James C. Defining 'American': Birthright Citizenship and the Original Understanding of the 14th Amendment (PDF). The Green Bag. 2006, 9 (4): 368 [2012-01-06]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2010-10-30).

- ^ Ho (2006), p. 372. "Repeal proponents ... quote Howard's introductory remarks to state that birthright citizenship 'will not, of course, include ... foreigners.' But that reads Howard's reference to 'aliens, who belong to the families of ambassadors or foreign ministers' out of the sentence. It also renders completely meaningless the subsequent dialogue between Senators Cowan and Conness over the wisdom of extending birthright citizenship to the children of Chinese immigrants and Gypsies."

- ^ Plyler v. Doe, 457 U.S. 202 (1982).

- ^ 168.0 168.1 Eisgruber, Christopher L. Birthright Citizenship and the Constitution. New York University Law Review. 1997, 72: 54–96.

- ^ Ho, James C. Commentary: Birthright Citizenship, the Fourteenth Amendment, and State Authority. University of Richmond Law Review. 2008-3, 42: 973. (原始内容存档于2012-04-02).

- ^ Dunklee, Dennis R.; Shoop, Robert J. The Principal's Quick-Reference Guide to School Law. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press. 2006: 241. ISBN 978-1-4129-2594-5.

- ^ Plyler v. Doe, 457 U.S. at 243. "I have no quarrel with the conclusion that the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment applies to aliens who, after their illegal entry into this country, are indeed physically 'within the jurisdiction' of a state."

- ^ Ho (2006), p. 374. "This sweeping language [in Wong Kim Ark] reaches all aliens regardless of immigration status. To be sure, the question of illegal aliens was not explicitly presented in Wong Kim Ark. But any doubt was put to rest in Plyler v. Doe...."

- ^ Ngai, Mae M. Birthright Citizenship and the Alien Citizen. Fordham Law Review. 2007, 75: 2524.

- ^ Birthright Citizenship Act of 2009, H.R. 1868, 111th Cong. 2009-4-2.

- ^ Birthright Citizenship Act of 2011, H.R. 140, 112th Cong. 2011-1-5.

- ^ Birthright Citizenship Act of 2011, S. 723, 112th Cong. 2011-4-5.

- ^ Proposing an amendment to the Constitution of the United States relating to United States citizenship, S.J.Res. 6, 111th Cong. 2009-1-16.

- ^ Proposing an amendment to the Constitution of the United States relating to United States citizenship, S.J.Res. 2, 112th Cong. 2011-1-25.

- ^ Citizenship-By-Birth Faces Challenges. National Public Radio. 2010-05-28 [2012-01-29].

- ^ Arizona Senate Panel Passes Sweeping Bills Targeting Illegals, Birthright Citizenship. FOX News. 2011-02-23 [2012-01-29].

- ^ ACLU of Arizona Responds to Anti-14th Amendment Proposal Introduced Today By Arizona Lawmakers. American Civil Liberties Union. 2011-01-27 [2012-01-29].

参考书目

- Foreign Affairs Manual, Volume 7 (7 FAM). United States Department of State. 2009-08-21 [2012-01-27]. (原始内容存档于2012-07-13).

- Eastman, John C. From Feudalism to Consent: Rethinking Birthright Citizenship. Legal Memorandum No. 18 (Washington D.C.: Heritage Foundation). 2006-03-30 [2011-07-02]. (原始内容存档于2011-07-04).

- Elinson, Elaine; Yogi, Stan. Wherever There's a Fight: How Runaway Slaves, Suffragists, Immigrants, Strikers and Poets Shaped Civil Liberties in California. Berkeley, CA: Heyday Books. 2009. ISBN 978-1-59714-114-7.

- Epps, Garrett. The Citizenship Clause: A 'Legislative History'. American University Law Review. 2010, 60 (2): 329–388 [2012-01-14]. (原始内容存档于2013-01-12).

- Glen, Patrick J. Wong Kim Ark and Sentencia que Declara Constitucional la Ley General de Migración 285-04 in Comparative Perspective: Constitutional Interpretation, Jus Soli Principles, and Political Morality. University of Miami Inter-American Law Review. Fall 2007, 39 (1): 67–109. JSTOR 40176768.

- Ho, James C. Defining 'American': Birthright Citizenship and the Original Understanding of the 14th Amendment (PDF). The Green Bag. 2006, 9 (4): 366 [2012-01-06]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2010-10-30).

- Rodriguez, Cristina M. The Second Founding: The Citizenship Clause, Original Meaning, and the Egalitarian Unity of the Fourteenth Amendment. University of Pennsylvania Journal of Constitutional Law. 2009, 11: 1363–1371.

- Salyer, Lucy E. Wong Kim Ark: The Contest Over Birthright Citizenship. Martin, David; Schuck, Peter (编). Immigration Stories. New York: Foundation Press. 2005. ISBN 1-58778-873-X.

- Semonche, John E. Charting the Future: The Supreme Court Responds to a Changing Society, 1890–1920. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. 1978. ISBN 0-313-20314-8. LCCN 77-94745.

- Woodworth, Marshall B. Citizenship of the United States under the Fourteenth Amendment. American Law Review (St. Louis: Review Pub. Company). 1896, 30: 535–555.

- Woodworth, Marshall B. Who Are Citizens of the United States? Wong Kim Ark Case. American Law Review (St. Louis: Review Pub. Company). 1898, 32: 554–561.

相关案例

- 帆船交易所诉法登案:11 U.S. (7 Cranch) 116 (1812)

- 斯科特诉桑福德案:60 U.S. 393 (1857)

- 屠宰场案:83 U.S. 36 (1873)

- 艾尔克诉威尔金斯案:112 U.S. 94 (1884)

- 美国诉黄金德案:169 U.S. 649 (1898)

- 亨尼斯诉理查森药品有限公司案(Hennessy v. Richardson Drug Co.):189 U.S. 25 (1903)

- 施尼克诉美国案:195 U.S. 65 (1904)

- 罗金发诉怀特案(Kwock Jan Fat v. White,音译):253 U.S. 454 (1920)

- 韦汀诉金宝案(Weedin v. Chin Bow,音译):274 U.S. 657 (1927)

- 莫里森诉加利福尼亚州案:291 U.S. 82 (1934)

- 佩金斯诉艾尔格案:307 U.S. 325 (1939)

- 里根诉金案:319 U.S. 753 (1943)(调卷令驳回)

- 瑞德诉科沃特案:354 U.S. 1 (1957)

- 西川诉杜尔斯案:356 U.S. 129 (1958)

- 肯尼迪诉门多扎-马丁尼兹案(Kennedy v. Mendoza-Martinez):372 U.S. 144 (1963)

- 罗杰斯诉贝勒案:401 U.S. 815 (1971)

- 普莱勒诉杜伊案:457 U.S. 202 (1982)

- 陆天申案:21 F. 905 (D.Cal. 1884)

- 贾福先诉美国案(Gee Fook Sing v. U.S.,音译):49 F. 146 (9th Cir. 1892)

- 里根诉金案:134 F.2d 413 (9th Cir. 1943)

- 拉邦诉移民归化局(Rabang v. INS):35 F.3d 1449 (9th Cir. 1994)

- 弗尔蒙特诉移民归化局案(Valmonte v. INS)136 F.3d 914 (2nd Cir. 1998)

- 奥弗吉诉阿什克罗夫特案(Oforji v. Ashcroft):354 F.3d 609 (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) (7th Cir. 2003)

- 诺洛斯诉霍尔德案(Nolos v. Holder):611 F.3d 279 (5th Cir. 2010)

- 黄金德案:71 F. 382 (N.D.Cal. 1896)

- 里根诉金案:49 F. Supp. 222 (N.D.Cal. 1942)

- 州法院

- 林奇诉克拉克案:3 N.Y.Leg.Obs. 236 (N.Y. 1844)

参见

外部链接

- United States v. Wong Kim Ark, 169 U.S. 649 (1898)的文本可参见:Justia · Findlaw · Cornell · OpenJurist