干扰素基因刺激蛋白

干扰素基因刺激蛋白( STING ),也称为跨膜蛋白 173 ( TMEM173 ) 和MPYS / MITA / ERIS ,是人类中由 STING1基因编码的蛋白质。[6]

STING 在先天免疫中发挥着重要作用。当细胞被病毒、分枝杆菌和细胞内寄生虫等细胞内病原体感染时,STING 会诱导I型干扰素产生。[7] I 型干扰素由 STING 介导,通过与分泌干扰素的同一细胞(自分泌信号)和附近的细胞(旁分泌信號)結合,保護受感染的細胞和附近的細胞免受局部感染。 )因此,它在控制诺如病毒感染等方面发挥着重要作用。[8]

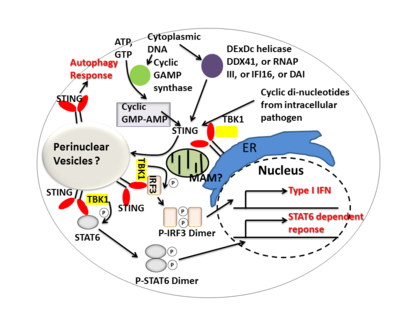

STING 既可作為直接胞質 DNA 傳感器(CDS),又可通過不同的分子機製作為I 型乾擾素信號轉導中的衔接蛋白。它已被证明可以通过TBK1激活下游转录因子STAT6和IRF3 ,这些因子负责抗病毒反应和针对细胞内病原体的先天免疫反应。[9]

结构

[编辑]

人類 STING 的氨基酸 1-379 包括 4 個跨膜区(TM) 和一个C 端结构域。 C 末端结构域(CTD:氨基酸 138-379)包含二聚結構域(DD)和羧基末端尾部(CTT:氨基酸 340-379)。[9]

STING 在细胞中形成对称二聚体。 STING 二聚体类似于蝴蝶,两个原聚体之间有一个深裂缝。每个 STING 原聚体的疏水残基在界面处彼此之间形成疏水相互作用。[9]

表达

[编辑]STING在外周淋巴组织的造血细胞中表达,包括T淋巴细胞、 NK细胞、骨髓细胞和单核细胞。研究还表明,STING 在肺、卵巢、心脏、平滑肌、视网膜、骨髓和阴道中高表达。[10][11]

定位

[编辑]STING 的亞細胞定位已被闡明為內質網蛋白。此外,STING 很可能與线粒体相关内质网膜 (MAM)(线粒体和内质网之间的界面)紧密相连。[12]在细胞内感染期间,STING 能够从内质网重新定位到可能參與外囊介導的運輸的核周囊泡。[12]在双链 DNA 刺激后,STING 还被证明与自噬蛋白、微管相关蛋白 1 轻链 3 (LC3)和自噬相关蛋白 9A共定位,表明它存在于自噬体中。[13]

功能

[编辑]STING 介導I 型乾擾素的產生,以響應細胞內 DNA 和多種細胞內病原體,包括病毒、细胞内细菌和细胞内寄生虫。[14]感染后,受感染细胞的 STING 可以感知细胞内病原体核酸的存在,然後誘導干擾素 β和 10 多種形式的干擾素α產生。受感染細胞產生的I型乾擾素可以發現並結合附近細胞的干擾素α/β受體,從而保護細胞免受局部感染。

抗病毒免疫力

[编辑]STING 可引發強大的I 型乾擾素免疫力,抵抗病毒感染。病毒進入後,病毒核酸存在于受感染细胞的细胞质中。多种DNA传感器,如DAI 、 RNA聚合酶III 、 IFI16 、 DDX41和cGAS ,可以检测外源核酸。识别病毒 DNA 后,DNA 传感器通过激活 STING 介导的干扰素反应来启动下游信号通路。[15]

腺病毒、单纯疱疹病毒、HSV-1 和 HSV-2 以及负链 RNA 病毒、水泡性口炎病毒(VSV) 已被證明能夠激活 STING 依賴性先天免疫反应。[16]

由于缺乏成功的 I 型干扰素反应,小鼠 STING 缺陷导致对 HSV-1 感染的致命易感性。[17]

Serine-358 的点突变抑制了蝙蝠中 STING-IFN 的激活,并被认为赋予蝙蝠作为储存宿主的能力。[18]

对抗细胞内细菌

[编辑]细胞内细菌(李斯特菌)已被证明可以通过 STING 刺激宿主免疫反应。[19] STING 可能在MCP-1和CCL7趋化因子的产生中发挥重要作用。在李斯特菌感染期間,STING 缺陷單核細胞在向肝臟遷移方面存在本質缺陷。通過這種方式,STING 通過調節单核细胞迁移来保护宿主免受感染。 STING 的激活可能是由细胞内细菌分泌的环二-AMP介导的。[19][20]

其他

[编辑]STING 可能是针对传染性生物体的保护性免疫的重要分子。例如,不能表达STING的动物更容易受到VSV 、 HSV-1和李斯特菌的感染,这表明其与人类传染病的潜在相关性。[21]

在宿主免疫中的作用

[编辑]儘管I 型乾擾素對於抵抗病毒絕對至關重要,但越來越多的文獻表明I 型乾擾素在 STING 介導的宿主免疫中的負面作用。恶性恶性疟原虫和伯氏瘧原蟲基因組中富含 AT 的莖環 DNA 基序以及結核分枝桿菌的細胞外 DNA 已被證明可以通過 STING 激活I 型乾擾素。[22][23] ESX1分泌系统介导的吞噬体膜的穿孔允许细胞外分枝杆菌DNA进入宿主细胞质DNA传感器,从而诱导巨噬细胞产生I型干扰素。高I 型干扰素特征导致结核分枝杆菌发病机制和长期感染。[23] STING-TBK1-IRF 介導的I 型乾擾素反應對於感染伯氏瘧原蟲的實驗動物中實驗性腦型瘧疾的發病機制至關重要。缺乏I 型乾擾素反應的實驗小鼠對實驗性腦型瘧疾有抵抗力。[22]

STING信号机制

[编辑]

STING 通过充当直接 DNA 传感器和信号转接蛋白來介導I 型乾擾素免疫反應。激活後,STING 會刺激TBK1活性,使IRF3或STAT6磷酸化。磷酸化的IRF3和STAT6二聚化,然後進入細胞核刺激參與宿主免疫反應的基因表達,如IFNB 、 CCL2 、 CCL20等[9][24]。cGAS 与双链 DNA 结合,激活其酶活性后将 ATP 及 GTP 转化成第二信使 cGAMP,与内质网表面 STING 结合。STING 在结合后变化构 象并转移至高尔基体结合 TANK 结合激酶 1(TANK binding kinase 1,TBK1)后 磷酸化干扰素调节因子(interferon regulatory factor,IRF)3,使其进入细胞核诱导干扰素表达。另外 STING 也可激活 IKK,磷酸化 IκB 家族促进 NF-κB 表达[25]。

一些报告表明 STING 与选择性自噬的激活有关。[13]结核杆菌已被证明能产生激活 STING 的胞质 DNA 配体,导致细菌泛素化并随后招募自噬相關蛋白,所有這些都是“選擇性”自噬靶向和針對結核桿菌的先天防御所必需的。[26]

總之,STING 協調對感染的多種免疫反應,包括誘導干擾素和 STAT6 依賴性反應和選擇性自噬反應。[9]

作为细胞质 DNA 传感器

[编辑]在細胞內病原體感染期間,在哺乳動物細胞的胞漿中檢測到由不同細菌種類產生的環狀二核苷酸-第二信使信號分子;這會導致TBK1 - IRF3的激活以及下游I 型乾擾素的產生。[9][27] STING 已被證明可以直接與環二 GMP結合,這種識別會導致細胞因子的產生,例如I 型乾擾素,這對於成功消除病原體至關重要。[28]胞质 cGAS 不具备核苷酸序列特异性,因此 STING 通路也 受自身 DNA 激活,细胞核泄漏或线粒体损伤时所释放的 DNA 可能过度激活 STING 通路,引起炎症反应甚至自身免疫疾病。

作为信号适配器

[编辑]DDX41是解旋酶 DEXDc 家族的成員,在骨髓樹突細胞中識別細胞內 DNA 並通過與 STING 直接關聯介導先天免疫反應。[29]其他 DNA 传感器 - DAI 、 RNA 聚合酶 III 、 IFI16也已被证明可以通过直接或间接相互作用激活 STING。[15]

環 GMP-AMP 合酶(cGAS) 屬於核苷酸轉移酶家族,能夠識別胞質 DNA 內容物,並通過產生第二信使環鳥苷單磷酸 - 腺苷單磷酸(環 GMP-AMP 或 cGAMP)來誘導 STING 依賴性干擾素反應。環 GMP-AMP結合的 STING 被激活後,它會增強TBK1磷酸化IRF3和STAT6的活性,从而产生下游I 型干扰素反应。[30][31]

有人提出,细胞内钙在 STING 通路的反应中发挥重要作用。[32]

相关

[编辑]- STING agonist——位於5號人類染色體的基因

参考

[编辑]- ^ 與干扰素基因刺激蛋白相關的疾病;在維基數據上查看/編輯參考.

- ^ 2.0 2.1 2.2 GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000184584、ENSG00000288243 - Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ 3.0 3.1 3.2 GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000024349 - Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ Human PubMed Reference:. National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Mouse PubMed Reference:. National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ STING1 stimulator of interferon response cGAMP interactor 1 [ Homo sapiens (human) ]. [2023-07-03]. (原始内容存档于2023-07-03).

- ^ Nakhaei P, Hiscott J, Lin R. STING-ing the antiviral pathway. Journal of Molecular Cell Biology. Jun 2010, 2 (3): 110–2. PMID 20022884. doi:10.1093/jmcb/mjp048

.

.

- ^ NYu P, Miao Z, Li Y, Bansal R, Peppelenbosch MP, Pan Q. cGAS-STING effectively restricts murine norovirus infection but antagonizes the antiviral action of N-terminus of RIG-I in mouse macrophage. Gut Microbes. 2021, 13 (1): 1959839. ISSN 1949-0976. PMC 8344765

. PMID 34347572. doi:10.1080/19490976.2021.1959839

. PMID 34347572. doi:10.1080/19490976.2021.1959839  .

.

- ^ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 Burdette DL, Vance RE. STING and the innate immune response to nucleic acids in the cytosol. Nature Immunology. Jan 2013, 14 (1): 19–26. PMID 23238760. S2CID 7968532. doi:10.1038/ni.2491.

- ^ EST expression profile of TMEM173. biogps org. biogps.org. [2023-07-03]. (原始内容存档于2011-08-20).

- ^ NCBI TMEM173 expression GEOprofile. NCBI. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geoprofiles. [2023-07-03]. (原始内容存档于2023-07-03).

- ^ 12.0 12.1 Ishikawa H, Barber GN. STING is an endoplasmic reticulum adaptor that facilitates innate immune signalling. Nature. Oct 2008, 455 (7213): 674–8. Bibcode:2008Natur.455..674I. PMC 2804933

. PMID 18724357. doi:10.1038/nature07317.

. PMID 18724357. doi:10.1038/nature07317.

- ^ 13.0 13.1 Saitoh T, Fujita N, Hayashi T, Takahara K, Satoh T, Lee H, Matsunaga K, Kageyama S, Omori H, Noda T, Yamamoto N, Kawai T, Ishii K, Takeuchi O, Yoshimori T, Akira S. Atg9a controls dsDNA-driven dynamic translocation of STING and the innate immune response. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. Dec 2009, 106 (49): 20842–6. Bibcode:2009PNAS..10620842S. PMC 2791563

. PMID 19926846. doi:10.1073/pnas.0911267106

. PMID 19926846. doi:10.1073/pnas.0911267106  .

.

- ^ Barber GN. Innate immune DNA sensing pathways: STING, AIMII and the regulation of interferon production and inflammatory responses. Current Opinion in Immunology. Feb 2011, 23 (1): 10–20. PMC 3881186

. PMID 21239155. doi:10.1016/j.coi.2010.12.015.

. PMID 21239155. doi:10.1016/j.coi.2010.12.015.

- ^ 15.0 15.1 Keating SE, Baran M, Bowie AG. Cytosolic DNA sensors regulating type I interferon induction (PDF). Trends in Immunology. Dec 2011, 32 (12): 574–81. PMID 21940216. doi:10.1016/j.it.2011.08.004. hdl:2262/68041

.

.

- ^ 引用错误:没有为名为

pmid21239155的参考文献提供内容 - ^ Ma Z, Damania B. The cGAS-STING Defense Pathway and Its Counteraction by Viruses. Cell Host & Microbe. February 2016, 19 (2): 150–8. PMC 4755325

. PMID 26867174. doi:10.1016/j.chom.2016.01.010.

. PMID 26867174. doi:10.1016/j.chom.2016.01.010.

- ^ Xie J, Li Y, Shen X, Got G, Zhu Y, Cui J, Wang L, Shi Z, Zhou P. Dampened STING-Dependent Interferon Activation in Bats. Cell Host & Microbe. March 2018, 23 (3): 297–301.e4. PMC 7104992

. PMID 29478775. doi:10.1016/j.chom.2018.01.006

. PMID 29478775. doi:10.1016/j.chom.2018.01.006  .

.

- ^ 19.0 19.1 Jin L, Getahun A, Knowles HM, Mogan J, Akerlund LJ, Packard TA, Perraud AL, Cambier JC. STING/MPYS mediates host defense against Listeria monocytogenes infection by regulating Ly6C(hi) monocyte migration. Journal of Immunology. Mar 2013, 190 (6): 2835–43. PMC 3593745

. PMID 23378430. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1201788.

. PMID 23378430. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1201788.

- ^ Woodward JJ, Iavarone AT, Portnoy DA. c-di-AMP secreted by intracellular Listeria monocytogenes activates a host type I interferon response. Science. Jun 2010, 328 (5986): 1703–5. Bibcode:2010Sci...328.1703W. PMC 3156580

. PMID 20508090. doi:10.1126/science.1189801.

. PMID 20508090. doi:10.1126/science.1189801.

- ^ Ishikawa H, Ma Z, Barber GN. STING regulates intracellular DNA-mediated, type I interferon-dependent innate immunity. Nature. Oct 2009, 461 (7265): 788–92. Bibcode:2009Natur.461..788I. PMC 4664154

. PMID 19776740. doi:10.1038/nature08476.

. PMID 19776740. doi:10.1038/nature08476.

- ^ 22.0 22.1 Sharma S, DeOliveira RB, Kalantari P, Parroche P, Goutagny N, Jiang Z, Chan J, Bartholomeu DC, Lauw F, Hall JP, Barber GN, Gazzinelli RT, Fitzgerald KA, Golenbock DT. Innate immune recognition of an AT-rich stem-loop DNA motif in the Plasmodium falciparum genome. Immunity. Aug 2011, 35 (2): 194–207. PMC 3162998

. PMID 21820332. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2011.05.016.

. PMID 21820332. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2011.05.016.

- ^ 23.0 23.1 Manzanillo PS, Shiloh MU, Portnoy DA, Cox JS. Mycobacterium tuberculosis activates the DNA-dependent cytosolic surveillance pathway within macrophages. Cell Host & Microbe. May 2012, 11 (5): 469–80. PMC 3662372

. PMID 22607800. doi:10.1016/j.chom.2012.03.007.

. PMID 22607800. doi:10.1016/j.chom.2012.03.007.

- ^ Chen H, Sun H, You F, Sun W, Zhou X, Chen L, Yang J, Wang Y, Tang H, Guan Y, Xia W, Gu J, Ishikawa H, Gutman D, Barber G, Qin Z, Jiang Z. Activation of STAT6 by STING is critical for antiviral innate immunity. Cell. Oct 2011, 147 (2): 436–46. PMID 22000020. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2011.09.022

.

.

- ^ Motwani, Mona; Pesiridis, Scott; Fitzgerald, Katherine A. DNA sensing by the cGAS–STING pathway in health and disease. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2019-07-29, 20 (11). ISSN 1471-0056. doi:10.1038/s41576-019-0151-1.

- ^ Watson RO, Manzanillo PS, Cox JS. Extracellular M. tuberculosis DNA targets bacteria for autophagy by activating the host DNA-sensing pathway. Cell. Aug 2012, 150 (4): 803–15. PMC 3708656

. PMID 22901810. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.040.

. PMID 22901810. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.040.

- ^ McWhirter SM, Barbalat R, Monroe KM, Fontana MF, Hyodo M, Joncker NT, Ishii KJ, Akira S, Colonna M, Chen ZJ, Fitzgerald KA, Hayakawa Y, Vance RE. A host type I interferon response is induced by cytosolic sensing of the bacterial second messenger cyclic-di-GMP. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. Aug 2009, 206 (9): 1899–911 [2023-07-03]. PMC 2737161

. PMID 19652017. doi:10.1084/jem.20082874. (原始内容存档于2018-07-20).

. PMID 19652017. doi:10.1084/jem.20082874. (原始内容存档于2018-07-20).

- ^ Burdette DL, Monroe KM, Sotelo-Troha K, Iwig JS, Eckert B, Hyodo M, Hayakawa Y, Vance RE. STING is a direct innate immune sensor of cyclic di-GMP. Nature. Oct 2011, 478 (7370): 515–8. Bibcode:2011Natur.478..515B. PMC 3203314

. PMID 21947006. doi:10.1038/nature10429.

. PMID 21947006. doi:10.1038/nature10429.

- ^ Zhang Z, Yuan B, Bao M, Lu N, Kim T, Liu YJ. The helicase DDX41 senses intracellular DNA mediated by the adaptor STING in dendritic cells. Nature Immunology. Oct 2011, 12 (10): 959–65. PMC 3671854

. PMID 21892174. doi:10.1038/ni.2091.

. PMID 21892174. doi:10.1038/ni.2091.

- ^ Wu J, Sun L, Chen X, Du F, Shi H, Chen C, Chen ZJ. Cyclic GMP-AMP is an endogenous second messenger in innate immune signaling by cytosolic DNA. Science. Feb 2013, 339 (6121): 826–30. Bibcode:2013Sci...339..826W. PMC 3855410

. PMID 23258412. doi:10.1126/science.1229963.

. PMID 23258412. doi:10.1126/science.1229963.

- ^ Sun L, Wu J, Du F, Chen X, Chen ZJ. Cyclic GMP-AMP synthase is a cytosolic DNA sensor that activates the type I interferon pathway. Science. Feb 2013, 339 (6121): 786–91. Bibcode:2013Sci...339..786S. PMC 3863629

. PMID 23258413. doi:10.1126/science.1232458.

. PMID 23258413. doi:10.1126/science.1232458.

- ^ Evidence for a role of calcium in STING signaling. 4 Jun 2017. bioRxiv 10.1101/145854

.

.