周细胞

| Pericyte 周细胞 | |

|---|---|

| |

| 标识字符 | |

| 拉丁文 | pericytus |

| MeSH | D020286 |

| TH | H3.09.02.0.02006 |

| FMA | FMA:63174 |

| 《显微解剖学术语》 [在维基数据上编辑] | |

此条目可参照英语维基百科相应条目来扩充。 |

周细胞(pericyte)又称外被细胞[1],旧名 Rouget氏细胞[2],是与微血管的血管壁结合的一类细胞,类似于血管平滑肌细胞,因定位于毛细血管及微血管基膜周围而得名[3]。周细胞最初被证明与血管收缩,调控局部微血管的血流量有关。调控血管生成及促进血管成熟等功能则被陆续认知,并且发现多种微血管病变伴随著周细胞结构及功能的异常。同时又发现周细胞有助于维持大脑的稳态和止血功能,并且维持血脑屏障[4]。中枢神经系统中缺乏周细胞则可以导致血脑屏障的破坏[4]。此外,周细胞是神经血管单位 (包括内皮细胞、星形胶质细胞和神经元) 的关键组成部分[5][6],故而周细胞的调控受到广泛关注,但是许多机制仍然未能阐明。

历史

[编辑]19世纪,Rouget首次提出周细胞的概念,即包绕在微静脉及毛细血管基膜的一类壁细胞,故而周细胞又可被称为Rouget氏细胞。随后齐默尔曼 (Zimmermann) 则根据周细胞位于血管周围的特性,将其命名为周细胞,并且沿用至今。周细胞最初被指与血管收缩及调控局部微血管管流量有关。之后的研究则发现周细胞与血管内皮细胞之间通过紧密的连接,可以影响着血管生成、血脑屏障通透性、脉管系统稳定性,以及细胞迁移与细胞分化等过程[7][8];并且可参与调节人体生理及病理的过程,故而与微血管屏障相关疾病的关系十分密切。在不同组织中的周细胞,其作用也存在着差异。

结构

[编辑]

在中枢神经系统中,周细胞包裹著毛细管内部的内皮细胞。相对于内皮细胞的扁平且细长的细胞核,因周细胞拥有着突出且呈圆形的细胞核,故而很容易就会区分这两种类型的细胞[5]。周细胞还伸出手指状的延伸物,并且缠绕在毛细血管壁上,使细胞可以调节毛细血管的血流[4]。周细胞和内皮细胞共享着基底膜,并且在基底膜上形成多种细胞间连接。这允许周细胞和邻近的细胞进行离子及其他小分子的交换[4]。此外,多种整联蛋白分子促进了周细胞与被基底膜分隔的内皮细胞之间的通讯[4]。这些细胞间连接部分中的重要分子包括N-钙粘蛋白、纤连蛋白、连接蛋白及各种整合素[5]。在基底膜的某些区域可以发现由纤连蛋白组成的粘着斑,而粘附斑则有助于基底膜与肌动蛋白组成的细胞骨架结构,以及周细胞和内皮细胞质膜的连接[4]。

起源

[编辑]目前认为不同组织器官的周细胞可能具有不同的胚胎起源[9]。在胚胎发生过程中,周细胞来源于轴旁中胚层与侧中胚层 (更准确是来自胚脏壁与体节)。Pouget等通过体节异体移植实验证实了主动脉周细胞主要来源于体节[10]。Cappellari等总结了主动脉流出道、头部及胸腺的周细胞来源于神经脊,而内脏血管的周细胞来源于间皮细胞,即覆盖在胸膜、腹膜及心包膜的单层扁平上皮[11]。有研究人员认为周细胞与血管平滑肌细胞同属于血管壁细胞,起源于间充质干细胞[12]。Yamanishi等通过动物实验进一步证实了神经脊细胞在周细胞的形成中扮演重要角色,提示周细胞的异质性与组织器官及细胞所依赖的微环境密切相关[13]。

功能

[编辑]骨骼肌再生和脂肪形成

[编辑]骨骼横纹肌中的周细胞有着两个不同的种群,每个种群都有各自的作用。 第一个周细胞亚型可以分化为脂肪细胞,而另一个则可以分化为肌肉细胞。 第一个周细胞亚型的特征是对巢蛋白(PDGFRβ+ CD146 + Nes-)呈阴性反应,第二个周细胞亚型的特征是对巢蛋白(PDGFRβ+ CD146 + Nes +)呈阳性反应。 虽然两种的周细胞亚型都能够响应由甘油或氯化钡诱导的损伤而进行增殖,但是1型周细胞仅响应于甘油的注射而产生成脂细胞,目前其参与脂肪积累的程度尚不清楚。2型周细胞则响应由甘油或氯化钡诱导的损伤而变为成肌细胞。

血管生成与内皮细胞的存活

[编辑]周细胞允许与内皮细胞进行分化与繁殖,以及形成血管分支。某些被称为微血管周细胞 (microvascular pericytes) 的周细胞会在毛细血管壁周围生长,并且有助于发挥这种功能。微血管周细胞可能不是具有收缩性的细胞,因为它们缺乏α-肌动蛋白同工型 (alpha-actin isoforms) ,以及在其他具收缩性的细胞中常见的结构。这些细胞通过间隙连接与内皮细胞进行信息传递,继而引起内皮细胞增殖或者被选择性地抑制。如果这个过程没有发生,可能会发生增生且异常的血管形态。这些类型的周细胞还可以吞噬外源蛋白 (exogenous proteins) 。这表明其可能源自小胶质细胞[14]。

目前已经提出了周细胞与其他细胞类型的谱系关系,包括平滑肌细胞[15] 、神经细胞[15]、少突先驱胶质细胞[16] 、肌细胞、脂肪细胞、成纤维细胞[17]及其他间充质干细胞。然而,这些细胞是否彼此分化是一个悬而未决的问题[17]。周细胞的再生能力会受衰老影响。这种多功能性是有益的,因为它们可以主动重塑整个身体的血管,从而可以与局部组织环境均匀融合。除了生成和重塑血管外,还发现周细胞可通过细胞凋亡或细胞毒性成分保护内皮细胞免于死亡[18] 。

有体内研究表明,周细胞释放一种称为周细胞氨基肽酶N/pAPN (pericytic aminopeptidase N/pAPN) 的激素,该激素可能促进血管生成。然而必须存在星形胶质细胞以确保周细胞与内皮细胞保持接触,否则不会发生适当的血管生成[19]。

另外,科研人员已经发现周细胞有助于内皮细胞的存活,因为它们在细胞串扰期间分泌BCL2L2蛋白。BCL2L2蛋白是该通路中的一种工具蛋白 (instrumental protein) ,可以增强VEGF-A的表达并阻止细胞凋亡[20] 。尽管对于为何血管内皮生长因子能直接负责预防细胞凋亡有一些推测,但据信它是负责调节细胞凋亡信号转导途径,并且抑制着酶 (会诱导细胞凋亡) 的活化。血管内皮生长因子实现此目的的两个生化机制是细胞外调节激酶1(ERK-1)的磷酸化,该激酶可维持细胞的存活,并且抑制着应激激活的蛋白激酶/c-jun-NH2激酶 (stress-activated protein kinase/c-jun-NH2 kinase) ,因为该激酶会促进细胞凋亡[21]。

血脑屏障

[编辑]周细胞对循环系统和中枢神经系统之间选择性渗透空间的形成和功能起著至关重要的作用。由内皮细胞组成的空间被称为血脑屏障,可以确保大脑和中枢神经系统的保护和正常功能。尽管普遍认为星形胶质细胞对于血脑屏障的形成至关重要,但是现在已经发现周细胞在很大程度上也起著相同作用。周细胞不仅负责内皮细胞之间紧密连接的形成及囊泡运输,还会通过抑制中枢神经系统免疫细胞的作用(因为可能会破坏血脑屏障的形成),并且减少表达可能会增加血管通透性的分子,从而允许血脑屏障的形成[22]。除了形成血脑屏障外,周细胞还控制着血管内以及血管与大脑之间的血流量,并且发挥积极作用。在具有较低周细胞覆盖率的动物模型中,分子以较高的频率跨越内皮细胞进行运输,从而使蛋白质进入大脑[23] 。理论上,周细胞的丧失或功能障碍也会令血脑屏障受到破坏而导致神经退行性疾病,例如阿兹海默症、帕金森氏症及肌萎缩性脊髓侧索硬化症等。

血流量

[编辑]周细胞可以调节血流。对于视网膜,已经有研究表明周膜改变其膜电位且引起钙流入的时候,周细胞就会收缩毛细血管[24]。在大脑中,则会在上游小动脉发生扩张之前,通过诱导周细胞扩张毛细血管,以增加局部的血流量,从而使小动脉出现扩张[25]。然而,这是具有争议性的。最近进行的一项研究声称周细胞不会表达收缩蛋白 (contractile proteins),并且不能在体内收缩[26] ,尽管该研究被批评使用了高度不符合常规的周细胞定义,该定义明确地排除了周细胞收缩的可能性[27]。目前认为有不同的信号通路调节着周细胞对毛细血管的收缩,以及平滑肌细胞对小动脉的收缩[28]。周细胞对维持血液循环很重要。在一项涉及缺乏周细胞成年小鼠的研究中,由于内皮细胞和周细胞的缺失,脑血流量会减少,同时发生血管退化。有研究指出缺乏周细胞的小鼠海马体中明显出现缺氧的情况增多,并且发炎,同时有着严重的学习和记忆障碍[29]。

临床显著性

[编辑]由于周细胞在维持和调节内皮细胞结构和血流中有着关键的作用,因此在许多病理中都可以看到周细胞的功能异常。 它们可能过量存在,导致高血压和形成肿瘤等疾病,或者在缺乏周细胞时导致神经退行性疾病。

血管瘤

[编辑]血管瘤的临床阶段具有生理差异。在血管瘤增生的早期(0-12个月),肿瘤会表达增殖细胞核抗原(proliferating cell nuclear antigen)、血管内皮生长因子和IV型胶原酶,前两者位于内皮和周细胞中,后者位于内皮中。血管标志物CD31、血管性假血友病因子(vWF)和平滑肌肌动蛋白(即周细胞的标志物)在增生期和退化期均存在,但在病灶完全退化后消失[30] 。

血管周皮细胞瘤

[编辑]

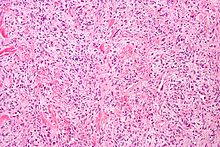

血管周皮细胞瘤是一种罕见的血管肿瘤,可以是良性或恶性的肿瘤,可能会以恶性形式转移到肺部、肝部、脑部和四肢。 通常在年龄较大的个体中发现,然而在儿童中也发现这种情况。由于无法使用光学显微镜将周细胞与其他类型的细胞区分开,因此难以诊断该肿瘤。血管周皮细胞瘤的治疗可能涉及手术切除和放射治疗,具体取决于骨渗透的水平,以及肿瘤发展的阶段[31]。

糖尿病性视网膜病变

[编辑]糖尿病患者的视网膜经常表现出周细胞减少的情况,并且这种减少是糖尿病性视网膜病早期阶段的特征性因素。有研究发现在糖尿病患者中,周细胞对于保护视网膜毛细血管的内皮细胞至关重要。随著周细胞的减少,毛细血管中会形成微动脉瘤,视网膜或会增加其血管通透性,从而通过黄斑水肿导致眼睛肿胀,抑或形成一些渗透到眼睛玻璃体膜中的新血管。最终的结果是视力下降或视力丧失[32] 。虽然目前不清楚为何糖尿病患者的周细胞会减少,但有研究人员声称是由于有毒的山梨糖醇和糖化终产物在周细胞中积累。细胞内山梨糖醇和果糖的积累导致渗透失衡,继而导致细胞损伤。高葡萄糖水平的存在还导致糖化终产物的积累,这同样会损害周细胞[33] 。

糖尿病肾病

[编辑]周细胞位于肾脏管状系统中,而肾小球内系膜细胞 (以下简称内系膜细胞) 和足细胞都是特殊周细胞样细胞,因为它们对维持肾小球结构及稳定肾小球功能均有重要作用[34]。基于内系膜细胞对肾小球血流量及滤过率的调节,其被认为是由未成熟的周细胞分化而来[35],而足细胞则来源于周细胞有丝分裂[34]。在一些模型中已证实内系膜细胞功能障碍是糖尿病肾病 (DN) 发生及发展的关键因素。在动物模型中发现,当足细胞损失超过20%,将导致不可逆性的肾小球损伤,其主要表现为白蛋白尿、肾小球硬化及肾小管间质纤维化,最终引致终末期肾功能衰竭[36]。内系膜细胞与周细胞失衡、内系膜细胞增多及足细胞减少均会加重DN。因此,抑制周细胞分化为内系膜细胞,同时促进周细胞有丝分裂产生更多足细胞是DN治疗的新思路。

神经退行性疾病

[编辑]有研究发现大脑中的周细胞丢失会导致神经退行性疾病和神经炎症。已衰老的大脑中,周细胞的凋亡可能是生长因子与周细胞受体之间传递讯息失败的结果。血小板衍生生长因子B(PDGFB)从脑血管中的内皮细胞释放出来,并且与周细胞上PDGFRB的受体结合,从而开始细胞的增殖。来自阿兹海默症及肌萎缩性脊髓侧索硬化症患者的人体组织的化学研究显示,患者体内出现周细胞的丧失和血脑屏障的破坏。与具有正常周细胞覆盖和阿兹海默症突变的小鼠相比,缺乏周细胞且具有阿兹海默症引起的突变的小鼠模型,其阿兹海默症的症状加剧了。

中风

[编辑]在患者出现中风的情况下,周细胞会收缩脑毛细血管且死亡。这可能导致血流量长期减少及血脑屏障的功能丧失,从而增加神经细胞的死亡[25]。

研究

[编辑]内皮细胞和周细胞的相互作用

[编辑]内皮细胞和周细胞是相互依存的,因此两个细胞之间无法正常传递信息会导致许多疾病[37]。内皮细胞和周细胞之间存在几种传递信息的途径。首先是由内皮细胞介导的转化生长因子信号传导。这对于周细胞分化至关重要[38][39] ,而血管生成素1和Tie-2信号则对内皮细胞的成熟和稳定至关重要[40] 。来自内皮细胞的血小板衍生生长因子信号通路募集周细胞,因此周细胞可以迁移到生长中的血管。如果该途径被阻断,将导致周细胞的数量减少[41] 。鞘氨醇-1-磷酸信号转导因通过G蛋白偶联受体的通讯而有助于募集周细胞。 鞘氨醇-1-磷酸是通过GTPases发出信号,从而促进N-钙粘蛋白向内皮膜的转运,并且加强与周细胞的联系[42] 。内皮细胞和周细胞之间的通讯很重要,抑制PDGF途径会导致周细胞的数量减少。不仅会导致内皮增生,还会令连接出现异常及造成糖尿病性视网膜的营养不良。周细胞的缺乏也会引致血管内皮生长因子的表达上调,从而导致血管出现渗漏和出血[43]。另外,血管生成素2可以作为Tie-2的拮抗剂[44] ,使内皮细胞不稳定,可能导致肿瘤的形成[45]。这解释了少量内皮细胞和周细胞的相互作用。与抑制PDGF途径相似,血管生成素2降低周细胞水平,导致糖尿病性视网膜病变[46]。

瘢痕

[编辑]星形胶质细胞通常与中枢神经系统的瘢痕形成过程有关,形成神经胶质瘢痕。有学者提出,周细胞亚型会以与神经胶质无关的方式参与这种瘢痕形成。它们通过分化为成肌纤维细胞及细胞外基质[47] ,促进了神经胶质瘢痕的形成。然而,这仍然是具有争议性的。因为最近的研究表明,这些疤痕研究中的细胞类型可能不是周细胞,而是成纤维细胞[48][49]。

参考资料

[编辑]- ^ 存档副本. [2022-06-22]. (原始内容存档于2022-06-22).

- ^ Dore-Duffy, P. Pericytes: pluripotent cells of the blood brain barrier.. Current pharmaceutical design. 2008, 14 (16): 1581–93 [2019-12-29]. PMID 18673199. doi:10.2174/138161208784705469. (原始内容存档于2019-12-29).

- ^ 陈宜瑜; 祁国荣; 宋大祥. 英汉生物学大词典 第一版. 北京: 科学出版社. 2009年一月: 1017 [2018-08-13]. ISBN 978-7-03-021675-5.

- ^ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Winkler, EA; Bell, RD; Zlokovic, BV. Central nervous system pericytes in health and disease.. Nature neuroscience. 2011-10-26, 14 (11): 1398–1405 [2019-12-29]. PMID 22030551. doi:10.1038/nn.2946. (原始内容存档于2019-12-29).

- ^ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Dore-Duffy, P; Cleary, K. Morphology and properties of pericytes.. Methods in molecular biology (Clifton, N.J.). 2011, 686: 49–68 [2019-12-29]. PMID 21082366. doi:10.1007/978-1-60761-938-3_2. (原始内容存档于2019-12-29).

- ^ Liebner, S; Czupalla, CJ; Wolburg, H. Current concepts of blood-brain barrier development.. The International journal of developmental biology. 2011, 55 (4-5): 467–76 [2019-12-29]. PMID 21769778. doi:10.1387/ijdb.103224sl. (原始内容存档于2019-12-29).

- ^ Caporali, A; Martello, A; Miscianinov, V; Maselli, D; Vono, R; Spinetti, G. Contribution of pericyte paracrine regulation of the endothelium to angiogenesis.. Pharmacology & therapeutics. 2017-03, 171: 56–64 [2019-12-29]. PMID 27742570. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2016.10.001. (原始内容存档于2019-12-29).

- ^ Dalkara, T; Gursoy-Ozdemir, Y; Yemisci, M. Brain microvascular pericytes in health and disease.. Acta neuropathologica. 2011-07, 122 (1): 1–9 [2019-12-29]. PMID 21656168. doi:10.1007/s00401-011-0847-6. (原始内容存档于2019-12-29).

- ^ Armulik, A; Genové, G; Betsholtz, C. Pericytes: developmental, physiological, and pathological perspectives, problems, and promises.. Developmental cell. 2011-08-16, 21 (2): 193–215 [2020-01-03]. PMID 21839917. doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2011.07.001. (原始内容存档于2020-01-03).

- ^ Pouget, C; Pottin, K; Jaffredo, T. Sclerotomal origin of vascular smooth muscle cells and pericytes in the embryo.. Developmental biology. 2008-03-15, 315 (2): 437–47 [2020-01-03]. PMID 18255054. doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.12.045. (原始内容存档于2020-01-03).

- ^ Cappellari, O; Cossu, G. Pericytes in development and pathology of skeletal muscle.. Circulation research. 2013-07-19, 113 (3): 341–7 [2020-01-03]. PMID 23868830. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.300203. (原始内容存档于2020-01-03).

- ^ Zhao, H; Feng, J; Seidel, K; Shi, S; Klein, O; Sharpe, P; Chai, Y. Secretion of shh by a neurovascular bundle niche supports mesenchymal stem cell homeostasis in the adult mouse incisor.. Cell stem cell. 2014-02-06, 14 (2): 160–73 [2020-01-03]. PMID 24506883. doi:10.1016/j.stem.2013.12.013. (原始内容存档于2020-01-03).

- ^ Yamanishi, E; Takahashi, M; Saga, Y; Osumi, N. Penetration and differentiation of cephalic neural crest-derived cells in the developing mouse telencephalon.. Development, growth & differentiation. 2012-12, 54 (9): 785–800 [2020-01-03]. PMID 23157329. doi:10.1111/dgd.12007. (原始内容存档于2020-01-03).

- ^ Pericyte, Astrocyte and Basal Lamina Association with the Blood Brain Barrier (BBB). University of Arizona Health Sciences. [2019-12-30]. (原始内容存档于2017-02-16).

- ^ 15.0 15.1 Birbrair A, Zhang T, Wang ZM, Messi ML, Enikolopov GN, Mintz A, Delbono O. Skeletal muscle pericyte subtypes differ in their differentiation potential. Stem Cell Research. January 2013, 10 (1): 67–84. PMC 3781014

. PMID 23128780. doi:10.1016/j.scr.2012.09.003.

. PMID 23128780. doi:10.1016/j.scr.2012.09.003.

- ^ Birbrair A, Zhang T, Wang ZM, Messi ML, Enikolopov GN, Mintz A, Delbono O. Skeletal muscle neural progenitor cells exhibit properties of NG2-glia. Experimental Cell Research. January 2013, 319 (1): 45–63. PMC 3597239

. PMID 22999866. doi:10.1016/j.yexcr.2012.09.008.

. PMID 22999866. doi:10.1016/j.yexcr.2012.09.008.

- ^ 17.0 17.1 Birbrair A, Zhang T, Wang ZM, Messi ML, Mintz A, Delbono O. Type-1 pericytes participate in fibrous tissue deposition in aged skeletal muscle. American Journal of Physiology. Cell Physiology. December 2013, 305 (11): C1098–113. PMC 3882385

. PMID 24067916. doi:10.1152/ajpcell.00171.2013.

. PMID 24067916. doi:10.1152/ajpcell.00171.2013.

- ^ Gerhardt H, Betsholtz C. Endothelial-pericyte interactions in angiogenesis. Cell and Tissue Research. October 2003, 314 (1): 15–23. PMID 12883993. doi:10.1007/s00441-003-0745-x.

- ^ Ramsauer M, Krause D, Dermietzel R. Angiogenesis of the blood-brain barrier in vitro and the function of cerebral pericytes. FASEB Journal. August 2002, 16 (10): 1274–6. PMID 12153997. doi:10.1096/fj.01-0814fje.

- ^ Franco M, Roswall P, Cortez E, Hanahan D, Pietras K. Pericytes promote endothelial cell survival through induction of autocrine VEGF-A signaling and Bcl-w expression. Blood. September 2011, 118 (10): 2906–17. PMC 3172806

. PMID 21778339. doi:10.1182/blood-2011-01-331694.

. PMID 21778339. doi:10.1182/blood-2011-01-331694.

- ^ Gupta K, Kshirsagar S, Li W, Gui L, Ramakrishnan S, Gupta P, Law PY, Hebbel RP. VEGF prevents apoptosis of human microvascular endothelial cells via opposing effects on MAPK/ERK and SAPK/JNK signaling. Experimental Cell Research. March 1999, 247 (2): 495–504. PMID 10066377. doi:10.1006/excr.1998.4359.

- ^ Daneman R, Zhou L, Kebede AA, Barres BA. Pericytes are required for blood-brain barrier integrity during embryogenesis. Nature. November 2010, 468 (7323): 562–6. PMC 3241506

. PMID 20944625. doi:10.1038/nature09513.

. PMID 20944625. doi:10.1038/nature09513.

- ^ Armulik A, Genové G, Mäe M, Nisancioglu MH, Wallgard E, Niaudet C, He L, Norlin J, Lindblom P, Strittmatter K, Johansson BR, Betsholtz C. Pericytes regulate the blood-brain barrier. Nature. November 2010, 468 (7323): 557–61. PMID 20944627. doi:10.1038/nature09522. hdl:10616/40288. (原始内容存档于2014-02-01) 使用

|archiveurl=需要含有|url=(帮助). 简明摘要 – Karolinska Institutet (October 14, 2010). - ^ Peppiatt CM, Howarth C, Mobbs P, Attwell D. Bidirectional control of CNS capillary diameter by pericytes. Nature. October 2006, 443 (7112): 700–4. PMC 1761848

. PMID 17036005. doi:10.1038/nature05193.

. PMID 17036005. doi:10.1038/nature05193.

- ^ 25.0 25.1 Hall CN, Reynell C, Gesslein B, Hamilton NB, Mishra A, Sutherland BA, O'Farrell FM, Buchan AM, Lauritzen M, Attwell D. Capillary pericytes regulate cerebral blood flow in health and disease. Nature. April 2014, 508 (7494): 55–60. PMC 3976267

. PMID 24670647. doi:10.1038/nature13165.

. PMID 24670647. doi:10.1038/nature13165.

- ^ Hill RA, Tong L, Yuan P, Murikinati S, Gupta S, Grutzendler J. Regional Blood Flow in the Normal and Ischemic Brain Is Controlled by Arteriolar Smooth Muscle Cell Contractility and Not by Capillary Pericytes. Neuron. July 2015, 87 (1): 95–110. PMC 4487786

. PMID 26119027. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2015.06.001.

. PMID 26119027. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2015.06.001.

- ^ Attwell D, Mishra A, Hall CN, O'Farrell FM, Dalkara T. What is a pericyte?. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. February 2016, 36 (2): 451–5. PMC 4759679

. PMID 26661200. doi:10.1177/0271678x15610340.

. PMID 26661200. doi:10.1177/0271678x15610340.

- ^ Mishra A, Reynolds JP, Chen Y, Gourine AV, Rusakov DA, Attwell D. Astrocytes mediate neurovascular signaling to capillary pericytes but not to arterioles. Nature Neuroscience. December 2016, 19 (12): 1619–1627. PMC 5131849

. PMID 27775719. doi:10.1038/nn.4428.

. PMID 27775719. doi:10.1038/nn.4428.

- ^ Bell RD, Winkler EA, Sagare AP, Singh I, LaRue B, Deane R, Zlokovic BV. Pericytes control key neurovascular functions and neuronal phenotype in the adult brain and during brain aging. Neuron. November 2010, 68 (3): 409–27. PMC 3056408

. PMID 21040844. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2010.09.043.

. PMID 21040844. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2010.09.043.

- ^ Munde P. Pericytes in Health and Disease. Celesta Software Pvt Ltd. [22 November 2014]. (原始内容存档于2019-12-30).

- ^ Gellman H. Solitary Fibrous Tumor. Medscape. [2 November 2011]. (原始内容存档于2020-11-23).

- ^ Hammes HP, Lin J, Renner O, Shani M, Lundqvist A, Betsholtz C, Brownlee M, Deutsch U. Pericytes and the pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes. October 2002, 51 (10): 3107–12. PMID 12351455. doi:10.2337/diabetes.51.10.3107.

- ^ Ciulla TA, Amador AG, Zinman B. Diabetic retinopathy and diabetic macular edema: pathophysiology, screening, and novel therapies. Diabetes Care. September 2003, 26 (9): 2653–64. PMID 12941734. doi:10.2337/diacare.26.9.2653.

- ^ 34.0 34.1 Lenoir, O; Jasiek, M; Hénique, C; Guyonnet, L; Hartleben, B; Bork, T; Chipont, A; Flosseau, K; Bensaada, I; Schmitt, A; Massé, JM; Souyri, M; Huber, TB; Tharaux, PL. Endothelial cell and podocyte autophagy synergistically protect from diabetes-induced glomerulosclerosis.. Autophagy. 2015, 11 (7): 1130–45 [2020-01-03]. PMID 26039325. doi:10.1080/15548627.2015.1049799. (原始内容存档于2020-01-03).

- ^ van Dijk, CG; Nieuweboer, FE; Pei, JY; Xu, YJ; Burgisser, P; van Mulligen, E; el Azzouzi, H; Duncker, DJ; Verhaar, MC; Cheng, C. The complex mural cell: pericyte function in health and disease.. International journal of cardiology. 2015, 190: 75–89 [2020-01-03]. PMID 25918055. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.03.258. (原始内容存档于2020-01-03).

- ^ Rutkowski, JM; Wang, ZV; Park, AS; Zhang, J; Zhang, D; Hu, MC; Moe, OW; Susztak, K; Scherer, PE. Adiponectin promotes functional recovery after podocyte ablation.. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2013-02, 24 (2): 268–82 [2020-01-03]. PMID 23334396. doi:10.1681/ASN.2012040414. (原始内容存档于2020-01-03).

- ^ Armulik A, Abramsson A, Betsholtz C. Endothelial/pericyte interactions. Circulation Research. September 2005, 97 (6): 512–23. PMID 16166562. doi:10.1161/01.RES.0000182903.16652.d7.

- ^ Carvalho RL, Jonker L, Goumans MJ, Larsson J, Bouwman P, Karlsson S, Dijke PT, Arthur HM, Mummery CL. Defective paracrine signalling by TGFbeta in yolk sac vasculature of endoglin mutant mice: a paradigm for hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia. Development. December 2004, 131 (24): 6237–47. PMID 15548578. doi:10.1242/dev.01529.

- ^ Hirschi KK, Rohovsky SA, D'Amore PA. PDGF, TGF-beta, and heterotypic cell-cell interactions mediate endothelial cell-induced recruitment of 10T1/2 cells and their differentiation to a smooth muscle fate. The Journal of Cell Biology. May 1998, 141 (3): 805–14. PMC 2132737

. PMID 9566978. doi:10.1083/jcb.141.3.805.

. PMID 9566978. doi:10.1083/jcb.141.3.805.

- ^ Thurston G, Suri C, Smith K, McClain J, Sato TN, Yancopoulos GD, McDonald DM. Leakage-resistant blood vessels in mice transgenically overexpressing angiopoietin-1. Science. December 1999, 286 (5449): 2511–4. PMID 10617467. doi:10.1126/science.286.5449.2511.

- ^ Bjarnegård M, Enge M, Norlin J, Gustafsdottir S, Fredriksson S, Abramsson A, Takemoto M, Gustafsson E, Fässler R, Betsholtz C. Endothelium-specific ablation of PDGFB leads to pericyte loss and glomerular, cardiac and placental abnormalities. Development. April 2004, 131 (8): 1847–57. PMID 15084468. doi:10.1242/dev.01080.

- ^ Paik JH, Skoura A, Chae SS, Cowan AE, Han DK, Proia RL, Hla T. Sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor regulation of N-cadherin mediates vascular stabilization. Genes & Development. October 2004, 18 (19): 2392–403. PMC 522989

. PMID 15371328. doi:10.1101/gad.1227804.

. PMID 15371328. doi:10.1101/gad.1227804.

- ^ Hellström M, Gerhardt H, Kalén M, Li X, Eriksson U, Wolburg H, Betsholtz C. Lack of pericytes leads to endothelial hyperplasia and abnormal vascular morphogenesis. The Journal of Cell Biology. April 2001, 153 (3): 543–53. PMC 2190573

. PMID 11331305. doi:10.1083/jcb.153.3.543.

. PMID 11331305. doi:10.1083/jcb.153.3.543.

- ^ Maisonpierre PC, Suri C, Jones PF, Bartunkova S, Wiegand SJ, Radziejewski C, Compton D, McClain J, Aldrich TH, Papadopoulos N, Daly TJ, Davis S, Sato TN, Yancopoulos GD. Angiopoietin-2, a natural antagonist for Tie2 that disrupts in vivo angiogenesis. Science. July 1997, 277 (5322): 55–60. PMID 9204896. doi:10.1126/science.277.5322.55.

- ^ Zhang L, Yang N, Park JW, Katsaros D, Fracchioli S, Cao G, O'Brien-Jenkins A, Randall TC, Rubin SC, Coukos G. Tumor-derived vascular endothelial growth factor up-regulates angiopoietin-2 in host endothelium and destabilizes host vasculature, supporting angiogenesis in ovarian cancer. Cancer Research. June 2003, 63 (12): 3403–12 [2020-01-03]. PMID 12810677. (原始内容存档于2014-01-23).

- ^ Hammes HP, Lin J, Wagner P, Feng Y, Vom Hagen F, Krzizok T, Renner O, Breier G, Brownlee M, Deutsch U. Angiopoietin-2 causes pericyte dropout in the normal retina: evidence for involvement in diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes. April 2004, 53 (4): 1104–10. PMID 15047628. doi:10.2337/diabetes.53.4.1104.

- ^ Göritz C, Dias DO, Tomilin N, Barbacid M, Shupliakov O, Frisén J. A pericyte origin of spinal cord scar tissue. Science. July 2011, 333 (6039): 238–42. PMID 21737741. doi:10.1126/science.1203165.

- ^ Soderblom C, Luo X, Blumenthal E, Bray E, Lyapichev K, Ramos J, Krishnan V, Lai-Hsu C, Park KK, Tsoulfas P, Lee JK. Perivascular fibroblasts form the fibrotic scar after contusive spinal cord injury. The Journal of Neuroscience. August 2013, 33 (34): 13882–7. PMC 3755723

. PMID 23966707. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2524-13.2013.

. PMID 23966707. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2524-13.2013.

- ^ Vanlandewijck M, He L, Mäe MA, Andrae J, Ando K, Del Gaudio F, Nahar K, Lebouvier T, Laviña B, Gouveia L, Sun Y, Raschperger E, Räsänen M, Zarb Y, Mochizuki N, Keller A, Lendahl U, Betsholtz C. A molecular atlas of cell types and zonation in the brain vasculature. Nature. February 2018, 554 (7693): 475–480. PMID 29443965. doi:10.1038/nature25739. hdl:10138/301079 (英语).