蛋白质超家族

蛋白质超家族(英语:protein superfamily)是对可以找到共同祖先的最大一组蛋白质的合称。一般而言,共同祖先是基于结构比对[1]和物理性质得出的,即使序列相似性不高,[2]也可能会具有共同祖先。蛋白质超家族中往往还会有内部联系相对更近的蛋白质家族。[2][3]

识别

[编辑]蛋白质超家族可以用多种方法进行鉴定。

序列相似性

[编辑]

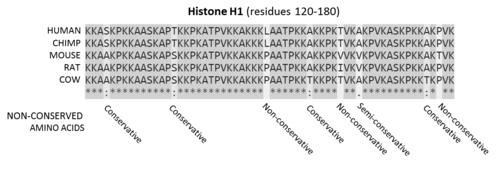

之前,不同蛋白质序列之间的相似性曾被作为推断同源性最常用的指标。[5]序列相似性被认为是相关性的一个指示物,因为相似的序列很有可能来自于基因重复和趋异进化,而不太可能来自于趋同进化。由于密码子简并的缘故,蛋白质的氨基酸序列一般比核酸序列更具有同源性。由于某些氨基酸的性质较为相似(在大小、电荷、疏水性等方面),发生在它们之间的保守突变往往对蛋白质的功能仅具有中性的影响。基本上,蛋白质序列中最保守的区段就是它们的结合活性位点和催化活性位点,因为这些区域发生的突变往往会对蛋白质功能产生负面的影响,从而不会在进化中流传下来。

然而,用序列相似性来推断同源性也有诸多不足。首先,相似的结构也可以来自于相似性较低的序列;其次,在漫长的进化过程中,相关序列之间的相似性也可能会降到无法识别的地步;最后,具有较多插入和删除突变的序列也很难用序列比对进行分析。例如,在PA蛋白酶超家族中,没有一个氨基酸残基是在所有成员中都相同的,即使是在催化三联体处的氨基酸也是如此。反之,PA超家族中的C04蛋白酶家族就是基于序列比对而划分出来的。

不过,序列相似性如今依然是推断同源性特征最常用的指标,因为已知的蛋白质序列数量要远远超过已知的蛋白质三级结构数量。受限于蛋白质结构数据的不足,蛋白质超家族的划分仍然十分依赖序列相似性的分析[6]。

结构相似性

[编辑]

蛋白质结构在进化上比蛋白质序列更为保守,具有相似结构的蛋白可以具有完全不同的的氨基酸序列。[7]在足够长的进化时间尺度上,氨基酸序列(一级结构)上的相似性几乎难以发现,但是二级结构的元件和三级结构的基序仍然是高度保守的。一些蛋白动力学特征[8]和构象改变的方式也有可能被保存下来,例如丝氨酸蛋白酶抑制剂(Serpin)超家族。[9]因此,即使序列上无法找到相似性,也可以通过蛋白质结构信息来推断其同源性。结构比对的程序,例如DALI,就可以通过分析蛋白的三维结构来寻找与之有相似折叠方式的其他蛋白。[10]然而,在少数情况下,相关的蛋白质也有可能进化出不同的结构,从而只能够用其他的手段鉴定其同源性。[11][12][13]

机理相似性

[编辑]同一蛋白质超家族中,虽然底物的特异性会有较大不同,酶促反应的机理大多是保守的。[14]具有催化活性的氨基酸残基一般也以相同的顺序出现在蛋白质序列中。[15]在PA蛋白酶超家族中,即使各个家族间催化三联体的氨基酸残基已经相差甚远,但它们采用的催化机理都是相似的——与蛋白质、多肽或氨基酸发生共价亲核反应。[16]但是,仅仅是机理的相似性无法证明同源性,因为一些相似的催化机理是由不同的超家族多次独立地,以趋同进化的方式得到的结果;[17][18][19]在同一超家族内也会存在一系列不同(或许在化学意义上类似)的催化机理。[14][20]

进化意义

[编辑]蛋白质超家族代表了我们现在鉴定蛋白质共同祖先的能力极限。[21]现今,这是基于直接证据的,可以划分出的最大进化类群。它们也因此代表了一些极为古老的进化事件。例如,有些蛋白质超家族的范围包括了生物类群的全部五界,说明了这些超家族的共同祖先蛋白存在于地球上所有生物的最后共同祖先(LUCA)体内。[22]

多样性

[编辑]大部分的蛋白质(66-80%的真核蛋白质和40-60%原核蛋白质)含有多个结构域,[5]在进化过程中,不同超家族的结构域之间会发生互相混合,事实上不与其他超家族发生重组的超家族是很难找到的。[5][1]当结构域之间发生重组时,其从N端到C端的顺序往往是保守的。此外,在自然界可以找到的结构域组合比理论上可能出现的情况要少得多,或许是自然选择的结果。[5]

蛋白质超家族的例子

[编辑]碱性磷酸酶超家族 - 具有相似的αβα三明治结构[23],催化机理也有相似之处。[24]

免疫球蛋白超家族 - 相似的反平行β折叠结构,在识别、结合、黏附功能上具有重要性。[27][28]

PA蛋白酶超家族 - 具有相似的类胰凝乳蛋白酶双β桶状结构,相似的蛋白酶解机理,但是序列相似性<10%。[2][29]

Ras超家族 - 相似的催化G结构域,由6个β片层和5个α螺旋组成。[30]

丝氨酸蛋白酶抑制剂超家族 - 具有相似的高能应力折叠,可以发生较大的构象改变,并从而抑制丝氨酸蛋白酶和半胱氨酸蛋白酶的活性。[9]

蛋白质超家族资源

[编辑]已有若干生物数据库收录了蛋白质超家族和结构折叠的数据,例如:

- Pfam - 蛋白质家族、序列比对数据

- PROSITE - 蛋白质结构域、家族、功能位点

- PIRSF - 超家族分类系统

也有可供在蛋白质资料库(PDB)中寻找特定相似结构的算法,例如:

- DALI - 基于距离对齐矩阵的结构比对方法

参见

[编辑]参考文献

[编辑]- ^ 1.0 1.1 Dali server: conservation mapping in 3D. Nucleic Acids Research. July 2010, 38 (Web Server issue): W545–9. PMC 2896194

. PMID 20457744. doi:10.1093/nar/gkq366.

. PMID 20457744. doi:10.1093/nar/gkq366.

- ^ 2.0 2.1 2.2 MEROPS: the database of proteolytic enzymes, their substrates and inhibitors. Nucleic Acids Research. January 2012, 40 (Database issue): D343–50. PMC 3245014

. PMID 22086950. doi:10.1093/nar/gkr987.

. PMID 22086950. doi:10.1093/nar/gkr987.

- ^ Updating the sequence-based classification of glycosyl hydrolases. The Biochemical Journal. June 1996, 316 (Pt 2): 695–6. PMC 1217404

. PMID 8687420. doi:10.1042/bj3160695.

. PMID 8687420. doi:10.1042/bj3160695.

- ^ Clustal FAQ #Symbols. Clustal. [8 December 2014]. (原始内容存档于2016-10-24).

- ^ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 The folding and evolution of multidomain proteins. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. April 2007, 8 (4): 319–30. PMID 17356578. doi:10.1038/nrm2144.

- ^ SUPFAM--a database of potential protein superfamily relationships derived by comparing sequence-based and structure-based families: implications for structural genomics and function annotation in genomes. Nucleic Acids Research. January 2002, 30 (1): 289–93. PMC 99061

. PMID 11752317. doi:10.1093/nar/30.1.289.

. PMID 11752317. doi:10.1093/nar/30.1.289.

- ^ Protein families and their evolution-a structural perspective. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 2005, 74 (1): 867–900. PMID 15954844. doi:10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.082803.133029.

- ^ Sequence evolution correlates with structural dynamics. Molecular Biology and Evolution. September 2012, 29 (9): 2253–63. PMC 3424413

. PMID 22427707. doi:10.1093/molbev/mss097.

. PMID 22427707. doi:10.1093/molbev/mss097.

- ^ 9.0 9.1 The serpins are an expanding superfamily of structurally similar but functionally diverse proteins. Evolution, mechanism of inhibition, novel functions, and a revised nomenclature. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. September 2001, 276 (36): 33293–6. PMID 11435447. doi:10.1074/jbc.R100016200.

- ^ Dali server update. Nucleic Acids Research. July 2016, 44 (W1): W351–5. PMC 4987910

. PMID 27131377. doi:10.1093/nar/gkw357.

. PMID 27131377. doi:10.1093/nar/gkw357.

- ^ Evolution of primate α and θ defensins revealed by analysis of genomes. Molecular Biology Reports. June 2014, 41 (6): 3859–66. PMID 24557891. doi:10.1007/s11033-014-3253-z.

- ^ Structural drift: a possible path to protein fold change. Bioinformatics. April 2005, 21 (8): 1308–10. PMID 15604105. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/bti227.

- ^ Proteins that switch folds. Current Opinion in Structural Biology. August 2010, 20 (4): 482–8. PMC 2928869

. PMID 20591649. doi:10.1016/j.sbi.2010.06.002.

. PMID 20591649. doi:10.1016/j.sbi.2010.06.002.

- ^ 14.0 14.1 Dessailly, Benoit H.; Dawson, Natalie L.; Das, Sayoni; Orengo, Christine A., Function Diversity Within Folds and Superfamilies, From Protein Structure to Function with Bioinformatics (Springer Netherlands), 2017: 295–325, ISBN 9789402410679, doi:10.1007/978-94-024-1069-3_9 (英语)

- ^ Causes of evolutionary rate variation among protein sites. Nature Reviews. Genetics. February 2016, 17 (2): 109–21. PMC 4724262

. PMID 26781812. doi:10.1038/nrg.2015.18 (英语).

. PMID 26781812. doi:10.1038/nrg.2015.18 (英语).

- ^ Handicap-Recover Evolution Leads to a Chemically Versatile, Nucleophile-Permissive Protease. ChemBioChem. September 2015, 16 (13): 1866–1869. PMC 4576821

. PMID 26097079. doi:10.1002/cbic.201500295.

. PMID 26097079. doi:10.1002/cbic.201500295.

- ^ Intrinsic evolutionary constraints on protease structure, enzyme acylation, and the identity of the catalytic triad. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. February 2013, 110 (8): E653–61. PMC 3581919

. PMID 23382230. doi:10.1073/pnas.1221050110.

. PMID 23382230. doi:10.1073/pnas.1221050110.

- ^ An evolving hierarchical family classification for glycosyltransferases. Journal of Molecular Biology. April 2003, 328 (2): 307–17. PMID 12691742. doi:10.1016/S0022-2836(03)00307-3.

- ^ Independent evolution of four heme peroxidase superfamilies. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. May 2015, 574: 108–19. PMC 4420034

. PMID 25575902. doi:10.1016/j.abb.2014.12.025.

. PMID 25575902. doi:10.1016/j.abb.2014.12.025.

- ^ Akiva, Eyal; Brown, Shoshana; Almonacid, Daniel E.; Barber, Alan E.; Custer, Ashley F.; Hicks, Michael A.; Huang, Conrad C.; Lauck, Florian; Mashiyama, Susan T. The Structure–Function Linkage Database. Nucleic Acids Research. 2013-11-23, 42 (D1): D521–D530 [2019-07-12]. ISSN 0305-1048. PMC 3965090

. PMID 24271399. doi:10.1093/nar/gkt1130. (原始内容存档于2021-05-13) (英语).

. PMID 24271399. doi:10.1093/nar/gkt1130. (原始内容存档于2021-05-13) (英语).

- ^ Protein structure and evolutionary history determine sequence space topology. Genome Research. March 2005, 15 (3): 385–92. PMC 551565

. PMID 15741509. arXiv:q-bio/0404040

. PMID 15741509. arXiv:q-bio/0404040  . doi:10.1101/gr.3133605.

. doi:10.1101/gr.3133605.

- ^ Protein superfamily evolution and the last universal common ancestor (LUCA). Journal of Molecular Evolution. October 2006, 63 (4): 513–25. PMID 17021929. doi:10.1007/s00239-005-0289-7.

- ^ SCOP. [28 May 2014]. (原始内容存档于2014-07-29).

- ^ Efficient, crosswise catalytic promiscuity among enzymes that catalyze phosphoryl transfer. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. January 2013, 1834 (1): 417–24. PMID 22885024. doi:10.1016/j.bbapap.2012.07.015.

- ^ Branden, Carl; Tooze, John. Introduction to protein structure 2nd. New York: Garland Pub. 1999. ISBN 978-0815323051.

- ^ Aplysia limacina myoglobin. Crystallographic analysis at 1.6 A resolution. Journal of Molecular Biology. February 1989, 205 (3): 529–44. PMID 2926816. doi:10.1016/0022-2836(89)90224-6.

- ^ The immunoglobulin fold. Structural classification, sequence patterns and common core. Journal of Molecular Biology. September 1994, 242 (4): 309–20. PMID 7932691. doi:10.1006/jmbi.1994.1582.

- ^ Cell adhesion molecules 1: immunoglobulin superfamily. Protein Profile. 1995, 2 (9): 963–1108. PMID 8574878.

- ^ Viral cysteine proteases are homologous to the trypsin-like family of serine proteases: structural and functional implications. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. November 1988, 85 (21): 7872–6. PMC 282299

. PMID 3186696. doi:10.1073/pnas.85.21.7872.

. PMID 3186696. doi:10.1073/pnas.85.21.7872.

- ^ The guanine nucleotide-binding switch in three dimensions. Science. November 2001, 294 (5545): 1299–304. PMID 11701921. doi:10.1126/science.1062023.