User:Peacearth/sandbox 3:修订间差异

←页面内容被替换为:'<noinclude>{{Template:用戶沙盒}}</noinclude> 阿耶波多 <noinclude>Category:沙盒</noinclude>' |

无编辑摘要 |

||

| 第1行: | 第1行: | ||

<noinclude>{{Template:用戶沙盒}}</noinclude> |

<noinclude>{{Template:用戶沙盒}}</noinclude> |

||

{{Pi box}} |

|||

阿耶波多 |

|||

[[File:2064 aryabhata-crp.jpg|thumb|100px|left|印度[[校際天文及天體物理學中心]]的阿里亞哈塔雕像,來自藝術家的想像,阿里亞哈塔的真實樣貌不明]] |

|||

'''阿里亚哈塔'''(Āryabhaṭa,或譯'''阿耶波多''','''阿里亚哈塔一世'''<ref name="Aryabhata the Elder">{{cite web|title=Aryabhata the Elder|url=http://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk/Biographies/Aryabhata_I.html|publisher=http://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk|accessdate=18 July 2012}}</ref><ref name="Publishing2010">{{cite book|author=Britannica Educational Publishing|title=The Britannica Guide to Numbers and Measurement|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=cuN7rH6RzikC&pg=PA97|accessdate=18 July 2012|date=15 August 2010|publisher=The Rosen Publishing Group|isbn=978-1-61530-218-5|pages=97–}}</ref>,公元476年-550年)<ref name="Ray2009">{{cite book|author=Bharati Ray|title=Different Types of History|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=9x5FX2RROZgC&pg=PA95|accessdate=24 June 2012|date=1 September 2009|publisher=Pearson Education India|isbn=978-81-317-1818-6|pages=95–}}</ref><ref name="Yadav2010">{{cite book|author=B. S. Yadav|title=Ancient Indian Leaps Into Mathematics|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=nwrw0Lv1vXIC&pg=PA88|accessdate=24 June 2012|date=28 October 2010|publisher=Springer|isbn=978-0-8176-4694-3|pages=88–}}</ref>是5世纪末[[印度]]的著名数学家及天文学家。他的作品包括[[阿里亚哈塔历书]](公元499年,他23岁的时候写成)<ref name="Roupp1997">{{cite book|author=Heidi Roupp|title=Teaching World History: A Resource Book|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=-UYag6dzk7YC&pg=PA112|accessdate=24 June 2012|year=1997|publisher=M.E. Sharpe|isbn=978-1-56324-420-9|pages=112–}}</ref>,分四部分。書中提供[[圓周率]]的一個近似值:((4 + 100) × 8 + 62000)/20000 = 62832/20000 = 3.1416。此外,他還根據天文觀測,提出[[日心說]],並發現[[食 (天文現象)|日月食]]的成因。 |

|||

印度在1975年發射的第一顆[[人造衛星]]以他的名字命名。 |

|||

---- |

|||

{{Infobox scholar |

|||

| image = 2064 aryabhata-crp.jpg |

|||

| caption = Statue of Aryabhata on the grounds of [[Inter-University Centre for Astronomy and Astrophysics|IUCAA]], [[Pune]]. As there is no known information regarding his appearance, any image of Aryabhata originates from an artist's conception. |

|||

| name = Āryabhaṭa |

|||

| fullname = |

|||

| birth_date = 476 CE |

|||

| birth_place = prob. [[Ashmaka]] |

|||

| death_date = 550 CE |

|||

| death_place = |

|||

| era = [[Gupta era]] |

|||

| region = [[India]] |

|||

| religion = [[Hinduism]] |

|||

| main_interests = [[Mathematics]], [[astronomy]] |

|||

| notable_ideas = Explanation of [[lunar eclipse]] and [[solar eclipse]], [[Earth's rotation|rotation of Earth on its axis]], [[Moonlight|reflection of light by moon]], [[Āryabhaṭa's sine table|sinusoidal functions]], [[Quadratic equation|solution of single variable quadratic equation]], [[Approximations of π|value of π correct to 4 decimal places]], circumference of [[Earth]] to 99.8% accuracy, calculation of the length of [[sidereal year]] |

|||

| major_works = [[Āryabhaṭīya]], Arya-[[siddhanta]] |

|||

| influences = [[Surya Siddhanta]] |

|||

| influenced = [[Lalla]], [[Bhaskara I]], [[Brahmagupta]], [[Varahamihira]] |

|||

}} |

|||

'''Aryabhata''' ({{lang-sa|आर्यभट}}; [[IAST]]: {{IAST|Āryabhaṭa}}) or '''Aryabhata I'''<ref name="Aryabhata the Elder">{{cite web|title=Aryabhata the Elder|url=http://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk/Biographies/Aryabhata_I.html|publisher=http://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk|accessdate=18 July 2012}}</ref><ref name="Publishing2010">{{cite book|author=Britannica Educational Publishing|title=The Britannica Guide to Numbers and Measurement|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=cuN7rH6RzikC&pg=PA97|accessdate=18 July 2012|date=15 August 2010|publisher=The Rosen Publishing Group|isbn=978-1-61530-218-5|pages=97–}}</ref> (476–550 [[Common Era|CE]])<ref name="Ray2009">{{cite book|author=Bharati Ray|title=Different Types of History|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=9x5FX2RROZgC&pg=PA95|accessdate=24 June 2012|date=1 September 2009|publisher=Pearson Education India|isbn=978-81-317-1818-6|pages=95–}}</ref><ref name="Yadav2010">{{cite book|author=B. S. Yadav|title=Ancient Indian Leaps Into Mathematics|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=nwrw0Lv1vXIC&pg=PA88|accessdate=24 June 2012|date=28 October 2010|publisher=Springer|isbn=978-0-8176-4694-3|pages=88–}}</ref> was the first of the major [[mathematician]]-[[astronomer]]s from the classical age of [[Indian mathematics]] and [[Indian astronomy]]. His works include the ''[[Āryabhaṭīya]]'' (499 CE, when he was 23 years old)<ref name="Roupp1997">{{cite book|author=Heidi Roupp|title=Teaching World History: A Resource Book|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=-UYag6dzk7YC&pg=PA112|accessdate=24 June 2012|date=1997|publisher=M.E. Sharpe|isbn=978-1-56324-420-9|pages=112–}}</ref> and the ''Arya-[[siddhanta]]''. |

|||

==Biography== |

|||

===Name=== |

|||

While there is a tendency to misspell his name as "Aryabhatta" by analogy with other names having the "[[bhatta]]" suffix, his name is properly spelled Aryabhata: every astronomical text spells his name thus,<ref name="sarma">{{Cite journal | author=[[K. V. Sarma]] | journal=Indian Journal of History of Science | date=2001 | pages=105–115 | title=Āryabhaṭa: His name, time and provenance | volume=36 | issue=4 | url=http://www.new.dli.ernet.in/rawdataupload/upload/insa/INSA_1/20005b67_105.pdf | ref=harv}}</ref> including [[Brahmagupta]]'s references to him "in more than a hundred places by name".<ref>{{cite book | date=1865 | contribution = Brief Notes on the Age and Authenticity of the Works of Aryabhata, Varahamihira, Brahmagupta, Bhattotpala, and Bhaskaracharya | title = Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland | author=[[Bhau Daji]] | page=392 | url=http://books.google.com/?id=fAsFAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA392&dq=aryabhata}}</ref> Furthermore, in most instances "Aryabhatta" would not fit the metre either.<ref name=sarma/> |

|||

===Time and place of birth=== |

|||

Aryabhata mentions in the ''Aryabhatiya'' that it was composed 3,600 years into the [[Kali Yuga]], when he was 23 years old. This corresponds to 499 CE, and implies that he was born in 476.<ref name=Yadav2010 /> |

|||

Aryabhata provides no information about his place of birth. The only information comes from [[Bhāskara I]], who describes Aryabhata as ''āśmakīya'', "one belonging to the ''[[aśmaka]]'' country." During the Buddha's time, a branch of the Aśmaka people settled in the region between the [[Narmada River|Narmada]] and [[Godavari]] rivers in central India; Aryabhata is believed to have been born there.<ref name=sarma/><ref name="Ansari"/> |

|||

====其他假說==== |

|||

It has been claimed that the ''aśmaka'' (Sanskrit for "stone") where Aryabhata originated may be the present day [[Kodungallur]] which was the historical capital city of ''Thiruvanchikkulam'' of ancient Kerala.<ref name="Menon">{{cite book|author=Menon|title=An Introduction to the History and Philosophy of Science|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=qi5Mcrm613oC&pg=PA52|accessdate=24 June 2012|publisher=Pearson Education India|isbn=978-81-317-2890-1|pages=52–}}</ref> This is based on the belief that Koṭuṅṅallūr was earlier known as Koṭum-Kal-l-ūr ("city of hard stones"); however, old records show that the city was actually Koṭum-kol-ūr ("city of strict governance"). Similarly, the fact that several commentaries on the Aryabhatiya have come from Kerala has been used to suggest that it was Aryabhata's main place of life and activity; however, many commentaries have come from outside Kerala, and the Aryasiddhanta was completely unknown in Kerala.<ref name=sarma/> K. Chandra Hari has argued for the Kerala hypothesis on the basis of astronomical evidence.<ref>{{citation | newspaper=[[The Hindu]] | url = http://www.hindu.com/2007/06/25/stories/2007062558250400.htm | title = Aryabhata lived in Ponnani? | date = June 25, 2007 | author = Radhakrishnan Kuttoor}}</ref> |

|||

Aryabhata mentions "Lanka" on several occasions in the ''Aryabhatiya'', but his "Lanka" is an abstraction, standing for a point on the equator at the same longitude as his [[Ujjayini]].<ref>See:<br> *{{Harvnb|Clark|1930}}<br> *{{Cite book | date=2000 | title = Indian Astronomy: An Introduction | author1=S. Balachandra Rao | publisher=Orient Blackswan | isbn=978-81-7371-205-0 | page=82 | url=http://books.google.com/?id=N3DE3GAyqcEC&pg=PA82&dq=lanka}}: "In Indian astronomy, the prime meridian is the great circle of the Earth passing through the north and south poles, Ujjayinī and Laṅkā, where Laṅkā was assumed to be on the Earth's equator."<br>*{{Cite book | date=2003 | title = Ancient Indian Astronomy | author1=L. Satpathy | publisher=Alpha Science Int'l Ltd. | isbn=978-81-7319-432-0 | page=200 | url=http://books.google.com/?id=nh6jgEEqqkkC&pg=PA200&dq=lanka}}: "Seven cardinal points are then defined on the equator, one of them called Laṅkā, at the intersection of the equator with the meridional line through Ujjaini. This Laṅkā is, of course, a fanciful name and has nothing to do with the island of Sri Laṅkā."<br>*{{Cite book | title = Classical Muhurta | author1=Ernst Wilhelm | publisher=Kala Occult Publishers | isbn=978-0-9709636-2-8 | page=44 | url=http://books.google.com/?id=3zMPFJy6YygC&pg=PA44&dq=lanka}}: "The point on the equator that is below the city of Ujjain is known, according to the Siddhantas, as Lanka. (This is not the Lanka that is now known as Sri Lanka; Aryabhata is very clear in stating that Lanka is 23 degrees south of Ujjain.)"<br>*{{Cite book | date=2006 | title = Pride of India: A Glimpse into India's Scientific Heritage | author1=R.M. Pujari | author2= Pradeep Kolhe | author3= N. R. Kumar | publisher=SAMSKRITA BHARATI | isbn=978-81-87276-27-2 | page=63 | url=http://books.google.com/?id=sEX11ZyjLpYC&pg=PA63&dq=lanka}}<br>*{{Cite book | date=1989 | title = The Surya Siddhanta: A Textbook of Hindu Astronomy | author1=Ebenezer Burgess | author2= Phanindralal Gangooly | publisher=Motilal Banarsidass Publ. | isbn=978-81-208-0612-2 | page=46 | url=http://books.google.com/?id=W0Uo_-_iizwC&pg=PA46&dq=lanka}}</ref> |

|||

===Education=== |

|||

It is fairly certain that, at some point, he went to Kusumapura for advanced studies and lived there for some time.<ref>{{cite book|last=Cooke|authorlink=Roger Cooke|title=History of Mathematics: A Brief Course |date=1997|chapter=''The Mathematics of the Hindus''|page=204|quote=Aryabhata himself (one of at least two mathematicians bearing that name) lived in the late 5th and the early 6th centuries at [[Kusumapura]] ([[Pataliutra]], a village near the city of Patna) and wrote a book called ''Aryabhatiya''.}}</ref> Both Hindu and Buddhist tradition, as well as [[Bhāskara I]] (CE 629), identify Kusumapura as [[Pāṭaliputra]], modern [[Patna]].<ref name=sarma/> A verse mentions that Aryabhata was the head of an institution (''{{IAST|kulapa}}'')<!--NOT "kulapati", see source--> at Kusumapura, and, because the university of [[Nalanda]] was in Pataliputra at the time and had an astronomical observatory, it is speculated that Aryabhata might have been the head of the Nalanda university as well.<ref name=sarma/> Aryabhata is also reputed to have set up an observatory at the Sun temple in [[Taregana]], Bihar.<ref>{{cite web| url=http://ncsm.gov.in/docs/Get%20ready%20for%20Solar%20eclipse.pdf| title = Get ready for solar eclipe| publisher = National Council of Science Museums, Ministry of Culture, Government of India | accessdate = 9 December 2009}}</ref> |

|||

==Works== |

|||

Aryabhata is the author of several treatises on [[mathematics]] and [[astronomy]], some of which are lost. |

|||

His major work, ''Aryabhatiya'', a compendium of mathematics and astronomy, was extensively referred to in the Indian mathematical literature and has survived to modern times. The mathematical part of the ''Aryabhatiya'' covers [[arithmetic]], [[algebra]], [[Trigonometry|plane trigonometry]], and [[spherical trigonometry]]. It also contains [[continued fraction]]s, [[quadratic equation]]s, sums-of-power series, and a [[Aryabhata's sine table|table of sines]]. |

|||

The ''Arya-siddhanta'', a lost work on astronomical computations, is known through the writings of Aryabhata's contemporary, [[Varahamihira]], and later mathematicians and commentators, including [[Brahmagupta]] and [[Bhaskara I]]. This work appears to be based on the older [[Surya Siddhanta]] and uses the midnight-day reckoning, as opposed to sunrise in ''Aryabhatiya''. It also contained a description of several astronomical instruments: the [[gnomon]] (''shanku-yantra''), a shadow instrument (''chhAyA-yantra''), possibly angle-measuring devices, semicircular and circular (''dhanur-yantra'' / ''chakra-yantra''), a cylindrical stick ''yasti-yantra'', an umbrella-shaped device called the ''chhatra-yantra'', and [[water clock]]s of at least two types, bow-shaped and cylindrical.<ref name = Ansari> |

|||

{{cite journal |

|||

|last=Ansari |

|||

|first=S.M.R. |

|||

|date=March 1977 |

|||

|title=Aryabhata I, His Life and His Contributions |

|||

|journal=Bulletin of the Astronomical Society of India |

|||

|volume=5 |

|||

|issue=1 |

|||

|pages=10–18 |

|||

|url= http://hdl.handle.net/2248/502 |

|||

|accessdate= 2011-01-22 |

|||

|ref=harv|bibcode = 1977BASI....5...10A }}</ref> |

|||

A third text, which may have survived in the [[Arabic language|Arabic]] translation, is ''Al ntf'' or ''Al-nanf''. It claims that it is a translation by Aryabhata, but the Sanskrit name of this work is not known. |

|||

Probably dating from the 9th century, it is mentioned by the [[Persian people|Persian]] scholar and chronicler of India, [[Abū Rayhān al-Bīrūnī]].<ref name = Ansari/> |

|||

===Aryabhatiya=== |

|||

{{Main|Aryabhatiya}} |

|||

Direct details of Aryabhata's work are known only from the ''Aryabhatiya''. The name "Aryabhatiya" is due to later commentators. Aryabhata himself may not have given it a name. His disciple [[Bhaskara I]] calls it ''Ashmakatantra'' (or the treatise from the Ashmaka). It is also occasionally referred to as ''Arya-shatas-aShTa'' (literally, Aryabhata's 108), because there are 108 verses in the text. It is written in the very terse style typical of [[sutra]] literature, in which each line is an aid to memory for a complex system. Thus, the explication of meaning is due to commentators. The text consists of the 108 verses and 13 introductory verses, and is divided into four ''pāda''s or chapters: |

|||

# ''Gitikapada'': (13 verses): large units of time—''kalpa'', ''manvantra'', and ''yuga''—which present a cosmology different from earlier texts such as Lagadha's ''[[Vedanga Jyotisha]]'' (c. 1st century BCE). There is also a table of sines (''[[jya]]''), given in a single verse. The duration of the planetary revolutions during a ''mahayuga'' is given as 4.32 million years. |

|||

# ''Ganitapada'' (33 verses): covering [[mensuration (mathematics)|mensuration]] (''kṣetra vyāvahāra''), arithmetic and geometric progressions, [[gnomon]] / shadows (''shanku''-''chhAyA''), simple, [[quadratic equations|quadratic]], [[simultaneous equations|simultaneous]], and [[diophantine equations|indeterminate]] equations (''kuṭṭaka''). |

|||

# ''Kalakriyapada'' (25 verses): different units of time and a method for determining the positions of planets for a given day, calculations concerning the intercalary month (''adhikamAsa''), ''kShaya-tithi''s, and a seven-day week with names for the days of week. |

|||

# ''Golapada'' (50 verses): Geometric/[[trigonometric]] aspects of the [[celestial sphere]], features of the [[ecliptic]], [[celestial equator]], node, shape of the earth, cause of day and night, rising of [[zodiacal sign]]s on horizon, etc. In addition, some versions cite a few [[colophon (publishing)|colophons]] added at the end, extolling the virtues of the work, etc. |

|||

The Aryabhatiya presented a number of innovations in mathematics and astronomy in verse form, which were influential for many centuries. The extreme brevity of the text was elaborated in commentaries by his disciple Bhaskara I (''Bhashya'', c. 600 CE) and by [[Nilakantha Somayaji]] in his ''Aryabhatiya Bhasya,'' (1465 CE). |

|||

==數學== |

|||

===Place value system and zero=== |

|||

The [[place-value]] system, first seen in the 3rd-century [[Bakhshali Manuscript]], was clearly in place in his work. While he did not use a symbol for [[zero]], the French mathematician [[Georges Ifrah]] argues that knowledge of zero was implicit in Aryabhata's [[place-value system]] as a place holder for the powers of ten with [[Null (mathematics)|null]] [[coefficients]].<ref>{{cite book |

|||

| author = George. Ifrah |

|||

| title = A Universal History of Numbers: From Prehistory to the Invention of the Computer |

|||

| publisher = John Wiley & Sons |

|||

| location = London |

|||

| date = 1998 |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

However, Aryabhata did not use the Brahmi numerals. Continuing the [[Sanskrit]]ic tradition from [[Vedic period|Vedic times]], he used letters of the alphabet to denote numbers, expressing quantities, such as the table of sines in a [[mnemonic]] form.<ref> |

|||

{{Cite book |

|||

| last1 = Dutta |

|||

| given1 = Bibhutibhushan |

|||

| surname2 = Singh |

|||

| given2 = Avadhesh Narayan |

|||

| date = 1962 |

|||

| title = History of Hindu Mathematics |

|||

| publisher = Asia Publishing House, Bombay |

|||

| isbn = 81-86050-86-8 |

|||

| ref = harv |

|||

| postscript = <!--None--> |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

===圓周率之估計=== |

|||

Aryabhata worked on the approximation for [[pi]] (<math>\pi</math>), and may have come to the conclusion that <math>\pi</math> is irrational. In the second part of the ''Aryabhatiyam'' ({{IAST|gaṇitapāda}} 10), he writes: |

|||

<blockquote> |

|||

''{{IAST|caturadhikam śatamaṣṭaguṇam dvāṣaṣṭistathā sahasrāṇām}} <br> |

|||

''{{IAST|ayutadvayaviṣkambhasyāsanno vṛttapariṇāhaḥ.}}<br /> |

|||

"Add four to 100, multiply by eight, and then add 62,000. By this rule the circumference of a circle with a diameter of 20,000 can be approached." |

|||

<ref> |

|||

{{cite book |

|||

|title= Geometry: Seeing, Doing, Understanding (Third Edition) |

|||

|last= Jacobs |

|||

|first= Harold R. |

|||

|date= 2003 |

|||

|publisher= W.H. Freeman and Company |

|||

|location= New York |

|||

|isbn= 0-7167-4361-2 |

|||

|page= 70}}</ref></blockquote> |

|||

This implies that the ratio of the circumference to the diameter is ((4 + 100) × 8 + 62000)/20000 = 62832/20000 = 3.1416, which is accurate to five [[significant figures]]. |

|||

It is speculated that Aryabhata used the word ''āsanna'' (approaching), to mean that not only is this an approximation but that the value is incommensurable (or [[irrational]]). If this is correct, it is quite a sophisticated insight, because the irrationality of pi was proved in Europe only in 1761 by [[Johann Heinrich Lambert|Lambert]].<ref> |

|||

{{cite book |

|||

| author = S. Balachandra Rao |

|||

| title = Indian Mathematics and Astronomy: Some Landmarks |

|||

| publisher = Jnana Deep Publications |

|||

| orig-year=First published 1994 |

|||

| date = 1998 |

|||

| location = Bangalore |

|||

| isbn = 81-7371-205-0 |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

After Aryabhatiya was translated into [[Arabic language|Arabic]] (c. 820 CE) |

|||

this approximation was mentioned in [[Al-Khwarizmi]]'s book on algebra.<ref name = Ansari/> |

|||

===Trigonometry=== |

|||

In Ganitapada 6, Aryabhata gives the area of a triangle as |

|||

: ''tribhujasya phalashariram samadalakoti bhujardhasamvargah'' |

|||

that translates to: "for a triangle, the result of a perpendicular with the half-side is the area."<ref>{{Cite book |

|||

| author = Roger Cooke |

|||

| title = History of Mathematics: A Brief Course |

|||

| publisher = Wiley-Interscience |

|||

| date=1997 |

|||

| chapter = The Mathematics of the Hindus |

|||

| isbn=0-471-18082-3 |

|||

| quote=Aryabhata gave the correct rule for the area of a triangle and an incorrect rule for the volume of a pyramid. (He claimed that the volume was half the height times the area of the base.)}}</ref> |

|||

Aryabhata discussed the concept of ''[[sine]]'' in his work by the name of ''[[ardha-jya]]'', which literally means "half-chord". For simplicity, people started calling it ''[[jya]]''. When Arabic writers translated his works from [[Sanskrit]] into Arabic, they referred it as ''jiba''. However, in Arabic writings, vowels are omitted, and it was abbreviated as ''jb''. Later writers substituted it with ''jaib'', meaning "pocket" or "fold (in a garment)". (In Arabic, ''jiba'' is a meaningless word.) Later in the 12th century, when [[Gherardo of Cremona]] translated these writings from Arabic into Latin, he replaced the Arabic ''jaib'' with its Latin counterpart, ''sinus'', which means "cove" or "bay"; thence comes the English word ''sine''.<ref>{{Cite book |

|||

| author = Howard Eves |

|||

| title = An Introduction to the History of Mathematics |

|||

| publisher = Saunders College Publishing House, New York |

|||

| date = 1990 |

|||

| edition = 6 |

|||

| page= 237 |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

===Indeterminate equations=== |

|||

A problem of great interest to [[Indian mathematicians]] since ancient times has been to find integer solutions to [[Diophantine equations]] that have the form ax + by = c. (This problem was also studied in ancient Chinese mathematics, and its solution is usually referred to as the [[Chinese remainder theorem]].) This is an example from [[Bhāskara I|Bhāskara]]'s commentary on Aryabhatiya: |

|||

: Find the number which gives 5 as the remainder when divided by 8, 4 as the remainder when divided by 9, and 1 as the remainder when divided by 7 |

|||

That is, find N = 8x+5 = 9y+4 = 7z+1. It turns out that the smallest value for N is 85. In general, diophantine equations, such as this, can be notoriously difficult. They were discussed extensively in ancient Vedic text [[Sulba Sutras]], whose more ancient parts might date to 800 BCE. Aryabhata's method of solving such problems, elaborated by Bhaskara in 621 CE, is called the ''{{IAST|kuṭṭaka}}'' (कुट्टक) method. ''Kuttaka'' means "pulverizing" or "breaking into small pieces", and the method involves a recursive algorithm for writing the original factors in smaller numbers. This algorithm became the standard method for solving first-order diophantine equations in Indian mathematics, and initially the whole subject of algebra was called ''kuṭṭaka-gaṇita'' or simply ''kuṭṭaka''.<ref> |

|||

Amartya K Dutta, [http://www.ias.ac.in/resonance/Volumes/07/10/0006-0022.pdf "Diophantine equations: The Kuttaka"], ''Resonance'', October 2002. Also see earlier overview: [http://www.ias.ac.in/resonance/Volumes/07/04/0004-0019.pdf ''Mathematics in Ancient India''].</ref> |

|||

===代數=== |

|||

In ''Aryabhatiya'', Aryabhata provided elegant results for the summation of [[series (mathematics)|series]] of squares and cubes:<ref>{{cite book|first=Carl B.| last=Boyer |authorlink=Carl Benjamin Boyer |title=A History of Mathematics |edition=Second |publisher=John Wiley & Sons, Inc. |date=1991 |isbn=0-471-54397-7 |page = 207 |chapter = The Mathematics of the Hindus |quote= "He gave more elegant rules for the sum of the squares and cubes of an initial segment of the positive integers. The sixth part of the product of three quantities consisting of the number of terms, the number of terms plus one, and twice the number of terms plus one is the sum of the squares. The square of the sum of the series is the sum of the cubes."}}</ref> |

|||

:<math>1^2 + 2^2 + \cdots + n^2 = {n(n + 1)(2n + 1) \over 6}</math> |

|||

and |

|||

:<math>1^3 + 2^3 + \cdots + n^3 = (1 + 2 + \cdots + n)^2</math> (see [[squared triangular number]]) |

|||

==天文學== |

|||

Aryabhata's system of astronomy was called the ''audAyaka system'', in which days are reckoned from ''uday'', dawn at ''lanka'' or "equator". Some of his later writings on astronomy, which apparently proposed a second model (or ''ardha-rAtrikA'', midnight) are lost but can be partly reconstructed from the discussion in [[Brahmagupta]]'s ''[[Khandakhadyaka]]''. In some texts, he seems to ascribe the apparent motions of the heavens to the [[Earth's rotation]]. He may have believed that the planet's orbits as [[Ellipse|elliptical]] rather than circular.<ref>J. J. O'Connor and E. F. Robertson, [http://www-groups.dcs.st-and.ac.uk/~history/Biographies/Aryabhata_I.html Aryabhata the Elder], [[MacTutor History of Mathematics archive]]'': |

|||

<br>{{quote|"He believes that the Moon and planets shine by reflected sunlight, incredibly he believes that the orbits of the planets are ellipses."}}</ref><ref name=Hayashi08Aryabhata>Hayashi (2008), ''Aryabhata I''</ref> |

|||

===太陽系之運行=== |

|||

Aryabhata correctly insisted that the earth rotates about its axis daily, and that the apparent movement of the stars is a relative motion caused by the rotation of the earth, contrary to the then-prevailing view, that the sky rotated. This is indicated in the first chapter of the ''Aryabhatiya'', where he gives the number of rotations of the earth in a ''yuga'',<ref>Aryabhatiya 1.3ab, see Plofker 2009, p. 111.</ref> and made more explicit in his ''gola'' chapter:<ref>[''achalAni bhAni samapashchimagAni ...'' – golapAda.9–10]. Translation from K. S. Shukla and K.V. Sarma, K. V. ''Āryabhaṭīya of Āryabhaṭa'', New Delhi: Indian National Science Academy, 1976. Quoted in Plofker 2009.</ref> |

|||

{{quote|In the same way that someone in a boat going forward sees an unmoving [object] going backward, so [someone] on the equator sees the unmoving stars going uniformly westward. The cause of rising and setting [is that] the sphere of the stars together with the planets [apparently?] turns due west at the equator, constantly pushed by the cosmic wind.}} |

|||

Aryabhata described a [[geocentric]] model of the solar system, in which the |

|||

Sun and Moon are each carried by [[epicycle]]s. They in turn revolve around |

|||

the Earth. In this model, which is also found in the ''Paitāmahasiddhānta'' (c. CE 425), the motions of the planets are each governed by two epicycles, a smaller ''manda'' (slow) and a larger ''śīghra'' (fast). |

|||

<ref> |

|||

{{Cite book |

|||

| last = Pingree |

|||

| first = David |

|||

| authorlink = David Pingree |

|||

| contribution = Astronomy in India |

|||

| editor-last = Walker |

|||

| editor-first = Christopher |

|||

| title = Astronomy before the Telescope |

|||

| pages = 123–142 |

|||

| publisher = British Museum Press |

|||

| place = London |

|||

| date = 1996 |

|||

| isbn = 0-7141-1746-3 |

|||

| ref = harv |

|||

| postscript = <!--None--> |

|||

}} pp. 127–9.</ref> The order of the planets in terms of distance from earth is taken as: the [[Moon]], [[Mercury (planet)|Mercury]], [[Venus]], the [[Sun]], [[Mars]], [[Jupiter]], [[Saturn]], and the [[Asterism (astronomy)|asterisms]]."<ref name=Ansari/> |

|||

The positions and periods of the planets was calculated relative to uniformly moving points. In the case of Mercury and Venus, they move around the Earth at the same mean speed as the Sun. In the case of Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn, they move around the Earth at specific speeds, representing each planet's motion through the zodiac. Most historians of astronomy consider that this two-epicycle model reflects elements of pre-Ptolemaic [[Hellenistic astronomy|Greek astronomy]].<ref>Otto Neugebauer, "The Transmission of Planetary Theories in Ancient and Medieval Astronomy," ''[[Scripta Mathematica]]'', 22 (1956), pp. 165–192; reprinted in Otto Neugebauer, ''Astronomy and History: Selected Essays,'' New York: Springer-Verlag, 1983, pp. 129–156. ISBN 0-387-90844-7</ref> Another element in Aryabhata's model, the ''śīghrocca'', the basic planetary period in relation to the Sun, is seen by some historians as a sign of an underlying [[heliocentric]] model.<ref>Hugh Thurston, ''Early Astronomy,'' New York: Springer-Verlag, 1996, pp. 178–189. ISBN 0-387-94822-8</ref> |

|||

===日食=== |

|||

Solar and lunar eclipses were scientifically explained by Aryabhata. He states that the [[Moon]] and planets shine by reflected sunlight. Instead of the prevailing cosmogony in which eclipses were caused by [[Rahu]] and [[Ketu (mythology)|Ketu]] (identified as the pseudo-planetary [[lunar nodes]]), he explains eclipses in terms of shadows cast by and falling on Earth. Thus, the lunar eclipse occurs when the moon enters into the Earth's shadow (verse gola.37). He discusses at length the size and extent of the Earth's shadow (verses gola.38–48) and then provides the computation and the size of the eclipsed part during an eclipse. Later Indian astronomers improved on the calculations, but Aryabhata's methods provided the core. His computational paradigm was so accurate that 18th-century scientist [[Guillaume Le Gentil]], during a visit to Pondicherry, India, found the Indian computations of the duration of the [[lunar eclipse]] of 30 August 1765 to be short by 41 seconds, whereas his charts (by Tobias Mayer, 1752) were long by 68 seconds.<ref name=Ansari/> |

|||

===Sidereal periods=== |

|||

Considered in modern English units of time, Aryabhata calculated the [[sidereal rotation]] (the rotation of the earth referencing the fixed stars) as 23 hours, 56 minutes, and 4.1 seconds;<ref name="Selin1997">{{cite book|editor=Helaine Selin|editor-link=Helaine Selin|author=R.C.Gupta|contribution=Āryabhaṭa|title=Encyclopaedia of the history of science, technology, and medicine in non-western cultures|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=raKRY3KQspsC&pg=PA72|accessdate=22 January 2011|date=31 July 1997|publisher=Springer|isbn=978-0-7923-4066-9|page=72}}</ref> the modern value is 23:56:4.091. Similarly, his value for the length of the [[sidereal year]] at 365 days, 6 hours, 12 minutes, and 30 seconds (365.25858 days)<ref>Ansari, p. 13, Table 1</ref> is an error of 3 minutes and 20 seconds over the length of a year (365.25636 days).<ref>''Aryabhatiya {{lang-mr|आर्यभटीय}}'', Mohan Apte, Pune, India, Rajhans Publications, 2009, p.25, ISBN 978-81-7434-480-9</ref> |

|||

===Heliocentrism=== |

|||

As mentioned, Aryabhata advocated an astronomical model in which the Earth turns on its own axis. His model also gave corrections (the ''śīgra'' anomaly) for the speeds of the planets in the sky in terms of the mean speed of the sun. Thus, it has been suggested that Aryabhata's calculations were based on an underlying [[heliocentrism|heliocentric]] model, in which the planets orbit the Sun,<ref>The concept of Indian heliocentrism has been advocated by B. L. van der Waerden, ''Das heliozentrische System in der griechischen, persischen und indischen Astronomie.'' Naturforschenden Gesellschaft in Zürich. Zürich:Kommissionsverlag Leeman AG, 1970.</ref><ref>B.L. van der Waerden, "The Heliocentric System in Greek, Persian and Hindu Astronomy", in David A. King and George Saliba, ed., ''From Deferent to Equant: A Volume of Studies in the History of Science in the Ancient and Medieval Near East in Honor of E. S. Kennedy'', Annals of the New York Academy of Science, 500 (1987), pp. 529–534.</ref><ref>{{Cite book|title=Early Astronomy|author=Hugh Thurston|publisher=[[Springer Science+Business Media|Springer]]|date=1996|isbn=0-387-94822-8|page=188|ref=harv|postscript=<!--None-->}}</ref> though this has been rebutted.<ref>Noel Swerdlow, "Review: A Lost Monument of Indian Astronomy," ''Isis'', 64 (1973): 239–243.</ref> It has also been suggested that aspects of Aryabhata's system may have been derived from an earlier, likely pre-Ptolemaic [[Greek astronomy|Greek]], heliocentric model of which Indian astronomers were unaware,<ref>Though [[Aristarchus of Samos]] (3rd century BCE) is credited with holding an heliocentric theory, the version of [[Greek astronomy]] known in ancient India as the ''[[Paulisa Siddhanta]]'' makes no reference to such a theory.</ref> though the evidence is scant.<ref>Dennis Duke, "The Equant in India: The Mathematical Basis of Ancient Indian Planetary Models." [[Archive for History of Exact Sciences]] 59 (2005): 563–576, n. 4 [http://people.scs.fsu.edu/~dduke/india8.pdf].</ref> The general consensus is that a synodic anomaly (depending on the position of the sun) does not imply a physically heliocentric orbit (such corrections being also present in late [[Babylonian astronomical diaries|Babylonian astronomical texts]]), and that Aryabhata's system was not explicitly heliocentric.<ref>{{cite book|last=Kim Plofker|title=Mathematics in India|publisher=Princeton University Press|location=Princeton, NJ|date=2009|page=111|isbn=0-691-12067-6}}</ref> |

|||

==Legacy== |

|||

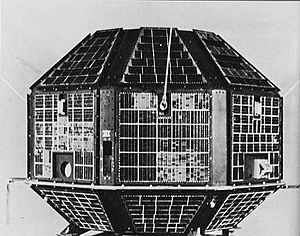

[[File:Aryabhata Satellite.jpg|thumb|300px|India's first satellite named after Aryabhata]] |

|||

Aryabhata's work was of great influence in the Indian astronomical tradition and influenced several neighbouring cultures through translations. The [[Arabic language|Arabic]] translation during the [[Islamic Golden Age]] (c. 820 CE), was particularly influential. Some of his results are cited by [[Al-Khwarizmi]] and in the 10th century [[Al-Biruni]] stated that Aryabhata's followers believed that the Earth rotated on its axis. |

|||

His definitions of [[sine]] (''[[jya]]''), cosine (''[[kojya]]''), versine (''[[utkrama-jya]]''), |

|||

and inverse sine (''otkram jya'') influenced the birth of [[trigonometry]]. He was also the first to specify sine and [[versine]] (1 − cos ''x'') tables, in 3.75° intervals from 0° to 90°, to an accuracy of 4 decimal places. |

|||

In fact, modern names "sine" and "cosine" are mistranscriptions of the words ''jya'' and ''kojya'' as introduced by Aryabhata. As mentioned, they were translated as ''jiba'' and ''kojiba'' in Arabic and then misunderstood by [[Gerard of Cremona]] while translating an Arabic geometry text to [[Latin]]. He assumed that ''jiba'' was the Arabic word ''jaib'', which means "fold in a garment", L. ''sinus'' (c. 1150).<ref>{{cite web |

|||

|title = Online Etymology Dictionary |

|||

|url = http://www.etymonline.com/ |

|||

|author = Douglas Harper |

|||

|date = 2001 |

|||

|accessdate = 2007-07-14 |

|||

| archiveurl= http://web.archive.org/web/20070713125946/http://www.etymonline.com/| archivedate= 13 July 2007 <!--DASHBot-->| deadurl= no}}</ref> |

|||

Aryabhata's astronomical calculation methods were also very influential. |

|||

Along with the trigonometric tables, they came to be widely used in the Islamic world and used to compute many [[Arabic]] astronomical tables ([[zij]]es). In particular, the astronomical tables in the work of the [[Al-Andalus|Arabic Spain]] scientist [[Al-Zarqali]] (11th century) were translated into Latin as the [[Tables of Toledo]] (12th century) and remained the most accurate [[ephemeris]] used in Europe for centuries. |

|||

Calendric calculations devised by Aryabhata and his followers have been in continuous use in India for the practical purposes of fixing the [[Panchangam]] (the [[Hindu calendar]]). In the Islamic world, they formed the basis of the [[Jalali calendar]] introduced in 1073 CE by a group of astronomers including [[Omar Khayyam]],<ref> |

|||

{{cite encyclopedia |

|||

|title = Omar Khayyam |

|||

|encyclopedia = The Columbia Encyclopedia |

|||

|date = May 2001 |

|||

|edition = 6 |

|||

|url = http://www.bartleby.com/65/om/OmarKhay.html |

|||

|accessdate =2007-06-10 |

|||

}}{{dead link|date=June 2012}}</ref> versions of which (modified in 1925) are the national calendars in use in [[Iran]] and [[Afghanistan]] today. The dates of the Jalali calendar are based on actual solar transit, as in Aryabhata and earlier [[Siddhanta]] calendars. This type of calendar requires an ephemeris for calculating dates. Although dates were difficult to compute, seasonal errors were less in the Jalali calendar than in the [[Gregorian calendar]]. |

|||

[[Aryabhatta Knowledge University]] (AKU), Patna has been established by Government of Bihar for the development and management of educational infrastructure related to technical, medical, management and allied professional education in his honour. The university is governed by Bihar State University Act 2008. |

|||

India's first satellite [[Aryabhata (satellite)|Aryabhata]] and the [[lunar crater]] [[Aryabhata (crater)|Aryabhata]] are named in his honour. An Institute for conducting research in astronomy, astrophysics and atmospheric sciences is the [[Aryabhatta Research Institute of Observational Sciences]] (ARIES) near Nainital, India. The inter-school [[Aryabhata Maths Competition]] is also named after him,<ref>{{cite news |title= Maths can be fun |url=http://www.hindu.com/yw/2006/02/03/stories/2006020304520600.htm |publisher=[[The Hindu]] |date = 3 February 2006|accessdate=2007-07-06 }}</ref> as is ''Bacillus aryabhata'', a species of bacteria discovered in the [[stratosphere]] by [[ISRO]] scientists in 2009.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2009/03/090318094642.htm|title=New Microorganisms Discovered In Earth's Stratosphere|publisher=ScienceDaily|date=18 March 2009}}</ref><ref name="ISRO Press Release 16 March 2009">{{cite web|title=ISRO Press Release 16 March 2009|url=http://www.isro.org/pressrelease/scripts/pressreleasein.aspx?Mar16_2009|publisher=ISRO|accessdate=24 June 2012}} {{Dead link|date=March 2015}}</ref> |

|||

== 參見 == |

|||

* {{IAST|[[Āryabhaṭa numeration]]}} |

|||

* {{IAST|[[Āryabhaṭa's sine table]]}} |

|||

* [[Indian mathematics]] |

|||

* [[List of Indian mathematicians]] |

|||

== 参考文献 == |

|||

{{Reflist|2}} |

|||

* {{cite book |

|||

| first=Roger |

|||

| last=Cooke |

|||

| title=The History of Mathematics: A Brief Course |

|||

| publisher=Wiley-Interscience |

|||

| date=1997 |

|||

| isbn=0-471-18082-3 |

|||

}} |

|||

* {{Cite book |

|||

| title = The {{IAST|Āryabhaṭīya}} of {{IAST|Āryabhaṭa}}: An Ancient Indian Work on Mathematics and Astronomy |

|||

| last=Clark | first=Walter Eugene |

|||

| date=1930 |

|||

| publisher=University of Chicago Press; reprint: Kessinger Publishing (2006) |

|||

| isbn=978-1-4254-8599-3 |

|||

| url=http://www.archive.org/details/The_Aryabhatiya_of_Aryabhata_Clark_1930 |

|||

| ref = harv |

|||

| postscript = <!-- Bot inserted parameter. Either remove it; or change its value to "." for the cite to end in a ".", as necessary. --> |

|||

}} |

|||

* [[Subhash Kak|Kak, Subhash C.]] (2000). 'Birth and Early Development of Indian Astronomy'. In {{Cite encyclopedia |

|||

| editor-last= Selin |

|||

| editor-first = Helaine |

|||

| editor-link = Helaine Selin |

|||

| date = 2000 |

|||

| title = Astronomy Across Cultures: The History of Non-Western Astronomy |

|||

| publisher = Boston: Kluwer |

|||

| ref = harv |

|||

| postscript = <!--None--> |

|||

| isbn = 0-7923-6363-9 |

|||

}} |

|||

* Shukla, Kripa Shankar. ''Aryabhata: Indian Mathematician and Astronomer.'' New Delhi: Indian National Science Academy, 1976. |

|||

* {{Cite journal |

|||

| last1 = Thurston |

|||

| first1 = H. |

|||

| date = 1994 |

|||

| title = Early Astronomy |

|||

| publisher = Springer-Verlag, New York |

|||

| ref = harv |

|||

| postscript = <!--None--> |

|||

| isbn = 0-387-94107-X |

|||

}} |

|||

{{Persondata |

|||

| NAME =Aryabhata |

|||

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES = |

|||

| SHORT DESCRIPTION = Indian mathematician |

|||

| DATE OF BIRTH = 476 |

|||

| PLACE OF BIRTH = prob. [[Ashmaka]] |

|||

| DATE OF DEATH = 550 |

|||

| PLACE OF DEATH = |

|||

}} |

|||

== 外部連結 == |

|||

{{commons category}} |

|||

{{Wikiquote}} |

|||

* [https://archive.org/details/The_Aryabhatiya_of_Aryabhata_Clark_1930 Eugene C. Clark's 1930 English translation] of ''The Aryabhatiya'' in various formats at the Internet Archive. |

|||

* {{MacTutor Biography|id=Aryabhata_I}} |

|||

* {{cite encyclopedia | editor = Thomas Hockey | last = Achar | first = Narahari | title=Āryabhaṭa I | encyclopedia = The Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers | publisher = Springer | date = 2007 | location = New York | page = 63 | url=http://islamsci.mcgill.ca/RASI/BEA/Aryabhata_I_BEA.htm | isbn=978-0-387-31022-0|display-editors=etal}} ([http://islamsci.mcgill.ca/RASI/BEA/Aryabhata_I_BEA.pdf PDF version]) |

|||

* [http://www.cse.iitk.ac.in/~amit/story/19_aryabhata.html ''Aryabhata and Diophantus' son'', [[Hindustan Times]] Storytelling Science column, Nov 2004] |

|||

* [http://www.wilbourhall.org/ Surya Siddhanta translations] |

|||

<nowiki>{{Authority control}} |

|||

[[Category:印度数学家]] |

|||

[[Category:印度天文学家]]</nowiki> |

|||

<noinclude>[[Category:沙盒]]</noinclude> |

<noinclude>[[Category:沙盒]]</noinclude> |

||

2015年8月21日 (五) 12:04的版本

| 這是Peacearth的用户页。用户沙盒是用户页的子頁面,属于用户的測試區,不是維基百科條目。 公用沙盒:主沙盒 | 使用指南沙盒一、二 | 模板沙盒 | 更多…… 此用户页的子頁面: 外觀選項: 用字選項: 如果您已经完成草稿,可以请求志愿者协助将其移动到条目空间。 |

| 圓周率 |

|---|

|

| 3.1415926535897932384626433... |

| 運用 |

| 證明 |

| 值 |

| 人物 |

| 歷史 |

| 文化 |

| 相關主題 |

阿里亚哈塔(Āryabhaṭa,或譯阿耶波多,阿里亚哈塔一世[1][2],公元476年-550年)[3][4]是5世纪末印度的著名数学家及天文学家。他的作品包括阿里亚哈塔历书(公元499年,他23岁的时候写成)[5],分四部分。書中提供圓周率的一個近似值:((4 + 100) × 8 + 62000)/20000 = 62832/20000 = 3.1416。此外,他還根據天文觀測,提出日心說,並發現日月食的成因。

印度在1975年發射的第一顆人造衛星以他的名字命名。

| Āryabhaṭa | |

|---|---|

| |

| 出生 | 476 CE prob. Ashmaka |

| 逝世 | 550 CE |

| 居住地 | India |

| 學術背景 | |

| 受影響自 | Surya Siddhanta |

| 學術工作 | |

| 年代 | Gupta era |

| 主要領域 | Mathematics, astronomy |

| 著名作品 | Āryabhaṭīya, Arya-siddhanta |

| 著名思想 | Explanation of lunar eclipse and solar eclipse, rotation of Earth on its axis, reflection of light by moon, sinusoidal functions, solution of single variable quadratic equation, value of π correct to 4 decimal places, circumference of Earth to 99.8% accuracy, calculation of the length of sidereal year |

| 施影响于 | Lalla, Bhaskara I, Brahmagupta, Varahamihira |

Aryabhata (梵語:आर्यभट; IAST: Āryabhaṭa) or Aryabhata I[1][2] (476–550 CE)[3][4] was the first of the major mathematician-astronomers from the classical age of Indian mathematics and Indian astronomy. His works include the Āryabhaṭīya (499 CE, when he was 23 years old)[5] and the Arya-siddhanta.

Biography

Name

While there is a tendency to misspell his name as "Aryabhatta" by analogy with other names having the "bhatta" suffix, his name is properly spelled Aryabhata: every astronomical text spells his name thus,[6] including Brahmagupta's references to him "in more than a hundred places by name".[7] Furthermore, in most instances "Aryabhatta" would not fit the metre either.[6]

Time and place of birth

Aryabhata mentions in the Aryabhatiya that it was composed 3,600 years into the Kali Yuga, when he was 23 years old. This corresponds to 499 CE, and implies that he was born in 476.[4]

Aryabhata provides no information about his place of birth. The only information comes from Bhāskara I, who describes Aryabhata as āśmakīya, "one belonging to the aśmaka country." During the Buddha's time, a branch of the Aśmaka people settled in the region between the Narmada and Godavari rivers in central India; Aryabhata is believed to have been born there.[6][8]

其他假說

It has been claimed that the aśmaka (Sanskrit for "stone") where Aryabhata originated may be the present day Kodungallur which was the historical capital city of Thiruvanchikkulam of ancient Kerala.[9] This is based on the belief that Koṭuṅṅallūr was earlier known as Koṭum-Kal-l-ūr ("city of hard stones"); however, old records show that the city was actually Koṭum-kol-ūr ("city of strict governance"). Similarly, the fact that several commentaries on the Aryabhatiya have come from Kerala has been used to suggest that it was Aryabhata's main place of life and activity; however, many commentaries have come from outside Kerala, and the Aryasiddhanta was completely unknown in Kerala.[6] K. Chandra Hari has argued for the Kerala hypothesis on the basis of astronomical evidence.[10]

Aryabhata mentions "Lanka" on several occasions in the Aryabhatiya, but his "Lanka" is an abstraction, standing for a point on the equator at the same longitude as his Ujjayini.[11]

Education

It is fairly certain that, at some point, he went to Kusumapura for advanced studies and lived there for some time.[12] Both Hindu and Buddhist tradition, as well as Bhāskara I (CE 629), identify Kusumapura as Pāṭaliputra, modern Patna.[6] A verse mentions that Aryabhata was the head of an institution (kulapa) at Kusumapura, and, because the university of Nalanda was in Pataliputra at the time and had an astronomical observatory, it is speculated that Aryabhata might have been the head of the Nalanda university as well.[6] Aryabhata is also reputed to have set up an observatory at the Sun temple in Taregana, Bihar.[13]

Works

Aryabhata is the author of several treatises on mathematics and astronomy, some of which are lost.

His major work, Aryabhatiya, a compendium of mathematics and astronomy, was extensively referred to in the Indian mathematical literature and has survived to modern times. The mathematical part of the Aryabhatiya covers arithmetic, algebra, plane trigonometry, and spherical trigonometry. It also contains continued fractions, quadratic equations, sums-of-power series, and a table of sines.

The Arya-siddhanta, a lost work on astronomical computations, is known through the writings of Aryabhata's contemporary, Varahamihira, and later mathematicians and commentators, including Brahmagupta and Bhaskara I. This work appears to be based on the older Surya Siddhanta and uses the midnight-day reckoning, as opposed to sunrise in Aryabhatiya. It also contained a description of several astronomical instruments: the gnomon (shanku-yantra), a shadow instrument (chhAyA-yantra), possibly angle-measuring devices, semicircular and circular (dhanur-yantra / chakra-yantra), a cylindrical stick yasti-yantra, an umbrella-shaped device called the chhatra-yantra, and water clocks of at least two types, bow-shaped and cylindrical.[8]

A third text, which may have survived in the Arabic translation, is Al ntf or Al-nanf. It claims that it is a translation by Aryabhata, but the Sanskrit name of this work is not known.

Probably dating from the 9th century, it is mentioned by the Persian scholar and chronicler of India, Abū Rayhān al-Bīrūnī.[8]

Aryabhatiya

Direct details of Aryabhata's work are known only from the Aryabhatiya. The name "Aryabhatiya" is due to later commentators. Aryabhata himself may not have given it a name. His disciple Bhaskara I calls it Ashmakatantra (or the treatise from the Ashmaka). It is also occasionally referred to as Arya-shatas-aShTa (literally, Aryabhata's 108), because there are 108 verses in the text. It is written in the very terse style typical of sutra literature, in which each line is an aid to memory for a complex system. Thus, the explication of meaning is due to commentators. The text consists of the 108 verses and 13 introductory verses, and is divided into four pādas or chapters:

- Gitikapada: (13 verses): large units of time—kalpa, manvantra, and yuga—which present a cosmology different from earlier texts such as Lagadha's Vedanga Jyotisha (c. 1st century BCE). There is also a table of sines (jya), given in a single verse. The duration of the planetary revolutions during a mahayuga is given as 4.32 million years.

- Ganitapada (33 verses): covering mensuration (kṣetra vyāvahāra), arithmetic and geometric progressions, gnomon / shadows (shanku-chhAyA), simple, quadratic, simultaneous, and indeterminate equations (kuṭṭaka).

- Kalakriyapada (25 verses): different units of time and a method for determining the positions of planets for a given day, calculations concerning the intercalary month (adhikamAsa), kShaya-tithis, and a seven-day week with names for the days of week.

- Golapada (50 verses): Geometric/trigonometric aspects of the celestial sphere, features of the ecliptic, celestial equator, node, shape of the earth, cause of day and night, rising of zodiacal signs on horizon, etc. In addition, some versions cite a few colophons added at the end, extolling the virtues of the work, etc.

The Aryabhatiya presented a number of innovations in mathematics and astronomy in verse form, which were influential for many centuries. The extreme brevity of the text was elaborated in commentaries by his disciple Bhaskara I (Bhashya, c. 600 CE) and by Nilakantha Somayaji in his Aryabhatiya Bhasya, (1465 CE).

數學

Place value system and zero

The place-value system, first seen in the 3rd-century Bakhshali Manuscript, was clearly in place in his work. While he did not use a symbol for zero, the French mathematician Georges Ifrah argues that knowledge of zero was implicit in Aryabhata's place-value system as a place holder for the powers of ten with null coefficients.[14]

However, Aryabhata did not use the Brahmi numerals. Continuing the Sanskritic tradition from Vedic times, he used letters of the alphabet to denote numbers, expressing quantities, such as the table of sines in a mnemonic form.[15]

圓周率之估計

Aryabhata worked on the approximation for pi (), and may have come to the conclusion that is irrational. In the second part of the Aryabhatiyam (gaṇitapāda 10), he writes:

caturadhikam śatamaṣṭaguṇam dvāṣaṣṭistathā sahasrāṇām

ayutadvayaviṣkambhasyāsanno vṛttapariṇāhaḥ.

"Add four to 100, multiply by eight, and then add 62,000. By this rule the circumference of a circle with a diameter of 20,000 can be approached."

This implies that the ratio of the circumference to the diameter is ((4 + 100) × 8 + 62000)/20000 = 62832/20000 = 3.1416, which is accurate to five significant figures.

It is speculated that Aryabhata used the word āsanna (approaching), to mean that not only is this an approximation but that the value is incommensurable (or irrational). If this is correct, it is quite a sophisticated insight, because the irrationality of pi was proved in Europe only in 1761 by Lambert.[17]

After Aryabhatiya was translated into Arabic (c. 820 CE) this approximation was mentioned in Al-Khwarizmi's book on algebra.[8]

Trigonometry

In Ganitapada 6, Aryabhata gives the area of a triangle as

- tribhujasya phalashariram samadalakoti bhujardhasamvargah

that translates to: "for a triangle, the result of a perpendicular with the half-side is the area."[18]

Aryabhata discussed the concept of sine in his work by the name of ardha-jya, which literally means "half-chord". For simplicity, people started calling it jya. When Arabic writers translated his works from Sanskrit into Arabic, they referred it as jiba. However, in Arabic writings, vowels are omitted, and it was abbreviated as jb. Later writers substituted it with jaib, meaning "pocket" or "fold (in a garment)". (In Arabic, jiba is a meaningless word.) Later in the 12th century, when Gherardo of Cremona translated these writings from Arabic into Latin, he replaced the Arabic jaib with its Latin counterpart, sinus, which means "cove" or "bay"; thence comes the English word sine.[19]

Indeterminate equations

A problem of great interest to Indian mathematicians since ancient times has been to find integer solutions to Diophantine equations that have the form ax + by = c. (This problem was also studied in ancient Chinese mathematics, and its solution is usually referred to as the Chinese remainder theorem.) This is an example from Bhāskara's commentary on Aryabhatiya:

- Find the number which gives 5 as the remainder when divided by 8, 4 as the remainder when divided by 9, and 1 as the remainder when divided by 7

That is, find N = 8x+5 = 9y+4 = 7z+1. It turns out that the smallest value for N is 85. In general, diophantine equations, such as this, can be notoriously difficult. They were discussed extensively in ancient Vedic text Sulba Sutras, whose more ancient parts might date to 800 BCE. Aryabhata's method of solving such problems, elaborated by Bhaskara in 621 CE, is called the kuṭṭaka (कुट्टक) method. Kuttaka means "pulverizing" or "breaking into small pieces", and the method involves a recursive algorithm for writing the original factors in smaller numbers. This algorithm became the standard method for solving first-order diophantine equations in Indian mathematics, and initially the whole subject of algebra was called kuṭṭaka-gaṇita or simply kuṭṭaka.[20]

代數

In Aryabhatiya, Aryabhata provided elegant results for the summation of series of squares and cubes:[21]

and

天文學

Aryabhata's system of astronomy was called the audAyaka system, in which days are reckoned from uday, dawn at lanka or "equator". Some of his later writings on astronomy, which apparently proposed a second model (or ardha-rAtrikA, midnight) are lost but can be partly reconstructed from the discussion in Brahmagupta's Khandakhadyaka. In some texts, he seems to ascribe the apparent motions of the heavens to the Earth's rotation. He may have believed that the planet's orbits as elliptical rather than circular.[22][23]

太陽系之運行

Aryabhata correctly insisted that the earth rotates about its axis daily, and that the apparent movement of the stars is a relative motion caused by the rotation of the earth, contrary to the then-prevailing view, that the sky rotated. This is indicated in the first chapter of the Aryabhatiya, where he gives the number of rotations of the earth in a yuga,[24] and made more explicit in his gola chapter:[25]

In the same way that someone in a boat going forward sees an unmoving [object] going backward, so [someone] on the equator sees the unmoving stars going uniformly westward. The cause of rising and setting [is that] the sphere of the stars together with the planets [apparently?] turns due west at the equator, constantly pushed by the cosmic wind.

Aryabhata described a geocentric model of the solar system, in which the Sun and Moon are each carried by epicycles. They in turn revolve around the Earth. In this model, which is also found in the Paitāmahasiddhānta (c. CE 425), the motions of the planets are each governed by two epicycles, a smaller manda (slow) and a larger śīghra (fast). [26] The order of the planets in terms of distance from earth is taken as: the Moon, Mercury, Venus, the Sun, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, and the asterisms."[8]

The positions and periods of the planets was calculated relative to uniformly moving points. In the case of Mercury and Venus, they move around the Earth at the same mean speed as the Sun. In the case of Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn, they move around the Earth at specific speeds, representing each planet's motion through the zodiac. Most historians of astronomy consider that this two-epicycle model reflects elements of pre-Ptolemaic Greek astronomy.[27] Another element in Aryabhata's model, the śīghrocca, the basic planetary period in relation to the Sun, is seen by some historians as a sign of an underlying heliocentric model.[28]

日食

Solar and lunar eclipses were scientifically explained by Aryabhata. He states that the Moon and planets shine by reflected sunlight. Instead of the prevailing cosmogony in which eclipses were caused by Rahu and Ketu (identified as the pseudo-planetary lunar nodes), he explains eclipses in terms of shadows cast by and falling on Earth. Thus, the lunar eclipse occurs when the moon enters into the Earth's shadow (verse gola.37). He discusses at length the size and extent of the Earth's shadow (verses gola.38–48) and then provides the computation and the size of the eclipsed part during an eclipse. Later Indian astronomers improved on the calculations, but Aryabhata's methods provided the core. His computational paradigm was so accurate that 18th-century scientist Guillaume Le Gentil, during a visit to Pondicherry, India, found the Indian computations of the duration of the lunar eclipse of 30 August 1765 to be short by 41 seconds, whereas his charts (by Tobias Mayer, 1752) were long by 68 seconds.[8]

Sidereal periods

Considered in modern English units of time, Aryabhata calculated the sidereal rotation (the rotation of the earth referencing the fixed stars) as 23 hours, 56 minutes, and 4.1 seconds;[29] the modern value is 23:56:4.091. Similarly, his value for the length of the sidereal year at 365 days, 6 hours, 12 minutes, and 30 seconds (365.25858 days)[30] is an error of 3 minutes and 20 seconds over the length of a year (365.25636 days).[31]

Heliocentrism

As mentioned, Aryabhata advocated an astronomical model in which the Earth turns on its own axis. His model also gave corrections (the śīgra anomaly) for the speeds of the planets in the sky in terms of the mean speed of the sun. Thus, it has been suggested that Aryabhata's calculations were based on an underlying heliocentric model, in which the planets orbit the Sun,[32][33][34] though this has been rebutted.[35] It has also been suggested that aspects of Aryabhata's system may have been derived from an earlier, likely pre-Ptolemaic Greek, heliocentric model of which Indian astronomers were unaware,[36] though the evidence is scant.[37] The general consensus is that a synodic anomaly (depending on the position of the sun) does not imply a physically heliocentric orbit (such corrections being also present in late Babylonian astronomical texts), and that Aryabhata's system was not explicitly heliocentric.[38]

Legacy

Aryabhata's work was of great influence in the Indian astronomical tradition and influenced several neighbouring cultures through translations. The Arabic translation during the Islamic Golden Age (c. 820 CE), was particularly influential. Some of his results are cited by Al-Khwarizmi and in the 10th century Al-Biruni stated that Aryabhata's followers believed that the Earth rotated on its axis.

His definitions of sine (jya), cosine (kojya), versine (utkrama-jya), and inverse sine (otkram jya) influenced the birth of trigonometry. He was also the first to specify sine and versine (1 − cos x) tables, in 3.75° intervals from 0° to 90°, to an accuracy of 4 decimal places.

In fact, modern names "sine" and "cosine" are mistranscriptions of the words jya and kojya as introduced by Aryabhata. As mentioned, they were translated as jiba and kojiba in Arabic and then misunderstood by Gerard of Cremona while translating an Arabic geometry text to Latin. He assumed that jiba was the Arabic word jaib, which means "fold in a garment", L. sinus (c. 1150).[39]

Aryabhata's astronomical calculation methods were also very influential. Along with the trigonometric tables, they came to be widely used in the Islamic world and used to compute many Arabic astronomical tables (zijes). In particular, the astronomical tables in the work of the Arabic Spain scientist Al-Zarqali (11th century) were translated into Latin as the Tables of Toledo (12th century) and remained the most accurate ephemeris used in Europe for centuries.

Calendric calculations devised by Aryabhata and his followers have been in continuous use in India for the practical purposes of fixing the Panchangam (the Hindu calendar). In the Islamic world, they formed the basis of the Jalali calendar introduced in 1073 CE by a group of astronomers including Omar Khayyam,[40] versions of which (modified in 1925) are the national calendars in use in Iran and Afghanistan today. The dates of the Jalali calendar are based on actual solar transit, as in Aryabhata and earlier Siddhanta calendars. This type of calendar requires an ephemeris for calculating dates. Although dates were difficult to compute, seasonal errors were less in the Jalali calendar than in the Gregorian calendar.

Aryabhatta Knowledge University (AKU), Patna has been established by Government of Bihar for the development and management of educational infrastructure related to technical, medical, management and allied professional education in his honour. The university is governed by Bihar State University Act 2008.

India's first satellite Aryabhata and the lunar crater Aryabhata are named in his honour. An Institute for conducting research in astronomy, astrophysics and atmospheric sciences is the Aryabhatta Research Institute of Observational Sciences (ARIES) near Nainital, India. The inter-school Aryabhata Maths Competition is also named after him,[41] as is Bacillus aryabhata, a species of bacteria discovered in the stratosphere by ISRO scientists in 2009.[42][43]

參見

参考文献

- ^ 1.0 1.1 Aryabhata the Elder. http://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk. [18 July 2012]. 外部链接存在于

|publisher=(帮助) - ^ 2.0 2.1 Britannica Educational Publishing. The Britannica Guide to Numbers and Measurement. The Rosen Publishing Group. 15 August 2010: 97– [18 July 2012]. ISBN 978-1-61530-218-5.

- ^ 3.0 3.1 Bharati Ray. Different Types of History. Pearson Education India. 1 September 2009: 95– [24 June 2012]. ISBN 978-81-317-1818-6.

- ^ 4.0 4.1 4.2 B. S. Yadav. Ancient Indian Leaps Into Mathematics. Springer. 28 October 2010: 88– [24 June 2012]. ISBN 978-0-8176-4694-3.

- ^ 5.0 5.1 Heidi Roupp. Teaching World History: A Resource Book. M.E. Sharpe. 1997: 112– [24 June 2012]. ISBN 978-1-56324-420-9. 引用错误:带有name属性“Roupp1997”的

<ref>标签用不同内容定义了多次 - ^ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 K. V. Sarma. Āryabhaṭa: His name, time and provenance (PDF). Indian Journal of History of Science. 2001, 36 (4): 105–115.

- ^ Bhau Daji. Brief Notes on the Age and Authenticity of the Works of Aryabhata, Varahamihira, Brahmagupta, Bhattotpala, and Bhaskaracharya. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. 1865: 392.

- ^ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 Ansari, S.M.R. Aryabhata I, His Life and His Contributions. Bulletin of the Astronomical Society of India. March 1977, 5 (1): 10–18 [2011-01-22]. Bibcode:1977BASI....5...10A.

- ^ Menon. An Introduction to the History and Philosophy of Science. Pearson Education India. : 52– [24 June 2012]. ISBN 978-81-317-2890-1.

- ^ Radhakrishnan Kuttoor, Aryabhata lived in Ponnani?, The Hindu, June 25, 2007

- ^ See:

*Clark 1930

*S. Balachandra Rao. Indian Astronomy: An Introduction. Orient Blackswan. 2000: 82. ISBN 978-81-7371-205-0.: "In Indian astronomy, the prime meridian is the great circle of the Earth passing through the north and south poles, Ujjayinī and Laṅkā, where Laṅkā was assumed to be on the Earth's equator."

*L. Satpathy. Ancient Indian Astronomy. Alpha Science Int'l Ltd. 2003: 200. ISBN 978-81-7319-432-0.: "Seven cardinal points are then defined on the equator, one of them called Laṅkā, at the intersection of the equator with the meridional line through Ujjaini. This Laṅkā is, of course, a fanciful name and has nothing to do with the island of Sri Laṅkā."

*Ernst Wilhelm. Classical Muhurta. Kala Occult Publishers. : 44. ISBN 978-0-9709636-2-8.: "The point on the equator that is below the city of Ujjain is known, according to the Siddhantas, as Lanka. (This is not the Lanka that is now known as Sri Lanka; Aryabhata is very clear in stating that Lanka is 23 degrees south of Ujjain.)"

*R.M. Pujari; Pradeep Kolhe; N. R. Kumar. Pride of India: A Glimpse into India's Scientific Heritage. SAMSKRITA BHARATI. 2006: 63. ISBN 978-81-87276-27-2.

*Ebenezer Burgess; Phanindralal Gangooly. The Surya Siddhanta: A Textbook of Hindu Astronomy. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. 1989: 46. ISBN 978-81-208-0612-2. - ^ Cooke. The Mathematics of the Hindus. History of Mathematics: A Brief Course. 1997: 204.

Aryabhata himself (one of at least two mathematicians bearing that name) lived in the late 5th and the early 6th centuries at Kusumapura (Pataliutra, a village near the city of Patna) and wrote a book called Aryabhatiya.

- ^ Get ready for solar eclipe (PDF). National Council of Science Museums, Ministry of Culture, Government of India. [9 December 2009].

- ^ George. Ifrah. A Universal History of Numbers: From Prehistory to the Invention of the Computer. London: John Wiley & Sons. 1998.

- ^ Dutta, Bibhutibhushan; Singh, Avadhesh Narayan. History of Hindu Mathematics. Asia Publishing House, Bombay. 1962. ISBN 81-86050-86-8.

- ^ Jacobs, Harold R. Geometry: Seeing, Doing, Understanding (Third Edition). New York: W.H. Freeman and Company. 2003: 70. ISBN 0-7167-4361-2.

- ^ S. Balachandra Rao. Indian Mathematics and Astronomy: Some Landmarks. Bangalore: Jnana Deep Publications. 1998 [First published 1994]. ISBN 81-7371-205-0.

- ^ Roger Cooke. The Mathematics of the Hindus. History of Mathematics: A Brief Course. Wiley-Interscience. 1997. ISBN 0-471-18082-3.

Aryabhata gave the correct rule for the area of a triangle and an incorrect rule for the volume of a pyramid. (He claimed that the volume was half the height times the area of the base.)

- ^ Howard Eves. An Introduction to the History of Mathematics 6. Saunders College Publishing House, New York. 1990: 237.

- ^ Amartya K Dutta, "Diophantine equations: The Kuttaka", Resonance, October 2002. Also see earlier overview: Mathematics in Ancient India.

- ^ Boyer, Carl B. The Mathematics of the Hindus. A History of Mathematics Second. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 1991: 207. ISBN 0-471-54397-7.

He gave more elegant rules for the sum of the squares and cubes of an initial segment of the positive integers. The sixth part of the product of three quantities consisting of the number of terms, the number of terms plus one, and twice the number of terms plus one is the sum of the squares. The square of the sum of the series is the sum of the cubes.

- ^ J. J. O'Connor and E. F. Robertson, Aryabhata the Elder, MacTutor History of Mathematics archive:

"He believes that the Moon and planets shine by reflected sunlight, incredibly he believes that the orbits of the planets are ellipses."

- ^ Hayashi (2008), Aryabhata I

- ^ Aryabhatiya 1.3ab, see Plofker 2009, p. 111.

- ^ [achalAni bhAni samapashchimagAni ... – golapAda.9–10]. Translation from K. S. Shukla and K.V. Sarma, K. V. Āryabhaṭīya of Āryabhaṭa, New Delhi: Indian National Science Academy, 1976. Quoted in Plofker 2009.

- ^ Pingree, David. Astronomy in India. Walker, Christopher (编). Astronomy before the Telescope. London: British Museum Press. 1996: 123–142. ISBN 0-7141-1746-3. pp. 127–9.

- ^ Otto Neugebauer, "The Transmission of Planetary Theories in Ancient and Medieval Astronomy," Scripta Mathematica, 22 (1956), pp. 165–192; reprinted in Otto Neugebauer, Astronomy and History: Selected Essays, New York: Springer-Verlag, 1983, pp. 129–156. ISBN 0-387-90844-7

- ^ Hugh Thurston, Early Astronomy, New York: Springer-Verlag, 1996, pp. 178–189. ISBN 0-387-94822-8

- ^ R.C.Gupta. Āryabhaṭa. Helaine Selin (编). Encyclopaedia of the history of science, technology, and medicine in non-western cultures. Springer. 31 July 1997: 72 [22 January 2011]. ISBN 978-0-7923-4066-9.

- ^ Ansari, p. 13, Table 1

- ^ Aryabhatiya 馬拉提語:आर्यभटीय, Mohan Apte, Pune, India, Rajhans Publications, 2009, p.25, ISBN 978-81-7434-480-9

- ^ The concept of Indian heliocentrism has been advocated by B. L. van der Waerden, Das heliozentrische System in der griechischen, persischen und indischen Astronomie. Naturforschenden Gesellschaft in Zürich. Zürich:Kommissionsverlag Leeman AG, 1970.

- ^ B.L. van der Waerden, "The Heliocentric System in Greek, Persian and Hindu Astronomy", in David A. King and George Saliba, ed., From Deferent to Equant: A Volume of Studies in the History of Science in the Ancient and Medieval Near East in Honor of E. S. Kennedy, Annals of the New York Academy of Science, 500 (1987), pp. 529–534.

- ^ Hugh Thurston. Early Astronomy. Springer. 1996: 188. ISBN 0-387-94822-8.

- ^ Noel Swerdlow, "Review: A Lost Monument of Indian Astronomy," Isis, 64 (1973): 239–243.

- ^ Though Aristarchus of Samos (3rd century BCE) is credited with holding an heliocentric theory, the version of Greek astronomy known in ancient India as the Paulisa Siddhanta makes no reference to such a theory.

- ^ Dennis Duke, "The Equant in India: The Mathematical Basis of Ancient Indian Planetary Models." Archive for History of Exact Sciences 59 (2005): 563–576, n. 4 [1].

- ^ Kim Plofker. Mathematics in India. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. 2009: 111. ISBN 0-691-12067-6.

- ^ Douglas Harper. Online Etymology Dictionary. 2001 [2007-07-14]. (原始内容存档于13 July 2007).

- ^ Omar Khayyam. The Columbia Encyclopedia 6. May 2001 [2007-06-10].[失效連結]

- ^ Maths can be fun. The Hindu. 3 February 2006 [2007-07-06].

- ^ New Microorganisms Discovered In Earth's Stratosphere. ScienceDaily. 18 March 2009.

- ^ ISRO Press Release 16 March 2009. ISRO. [24 June 2012]. [失效連結]

- Cooke, Roger. The History of Mathematics: A Brief Course. Wiley-Interscience. 1997. ISBN 0-471-18082-3.

- Clark, Walter Eugene. The Āryabhaṭīya of Āryabhaṭa: An Ancient Indian Work on Mathematics and Astronomy. University of Chicago Press; reprint: Kessinger Publishing (2006). 1930. ISBN 978-1-4254-8599-3.

- Kak, Subhash C. (2000). 'Birth and Early Development of Indian Astronomy'. In Selin, Helaine (编). Astronomy Across Cultures: The History of Non-Western Astronomy. Boston: Kluwer. 2000. ISBN 0-7923-6363-9.

- Shukla, Kripa Shankar. Aryabhata: Indian Mathematician and Astronomer. New Delhi: Indian National Science Academy, 1976.

- Thurston, H. Early Astronomy. Springer-Verlag, New York. 1994. ISBN 0-387-94107-X.

外部連結

- Eugene C. Clark's 1930 English translation of The Aryabhatiya in various formats at the Internet Archive.

- 約翰·J·奧康納; 埃德蒙·F·羅伯遜, Aryabhata_I, MacTutor数学史档案 (英语)

- Achar, Narahari. Āryabhaṭa I. Thomas Hockey; et al (编). The Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers. New York: Springer: 63. 2007. ISBN 978-0-387-31022-0. (PDF version)

- Aryabhata and Diophantus' son, Hindustan Times Storytelling Science column, Nov 2004

- Surya Siddhanta translations

{{Authority control}} [[Category:印度数学家]] [[Category:印度天文学家]]