能量密度

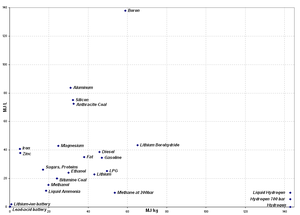

能量密度是指在一定的空间或质量物质中储存能量的大小。如果是按质量来判定一般被称为比能。

| 数量级 |

|---|

| 单位换算 |

能量密度表

此表给出了完整系统的能量密度,包含了一切必要的外部条件,如氧化剂和热源。

| 排序 | 存储形式 | 质量能量密度(MJ/kg) | 容积能量密度(MJ/L) | 峰值回收效率 % |

实际回收效率 % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 反物质[1] | 89,875,517,873.681,764 | |||

| 2 | 黑洞吸积盘(聚变)[2] | 8,987,551,787.368,176,4~35,950,207,149.472,705,6 | |||

| 3 | 氕核聚变(太阳的能量来源) | 645,000,000 | |||

| 4 | 氘-氚聚变 | 337,000,000 | |||

| 5 | 核裂变(100% 铀-235)(用于核武器)[3] | 88,250,000 | 1,500,000,000 | ||

| 6 | 钍燃料[3] | 79,420,000 | 929,214,000 | ||

| 7 | 核武器当量-重量比的理论极限[4] | 25,104,000 | |||

| 8 | 天然铀(99.3% U-238, 0.7% U-235)用于快中子增殖反应堆[5] | 24,000,000 | 50%[6] | ||

| 9 | B-41核弹(有资料显示的最高当量-重量比核武器)[4] | 21,756,800 | |||

| 10 | 沙皇炸弹设计爆炸弹[4] | 16,736,000 | |||

| 11 | 沙皇炸弹实际爆炸弹[4] | 8,987,851.85 | |||

| 12 | W88核弹头[4] | 5,520,055.55 | |||

| 13 | 浓缩铀(3.5% U235)用于轻水反应堆 | 3,456,000 | 30%[7] | ||

| 14 | 钚-238 α衰变 | 2,239,000 | |||

| 15 | 核同质异能素Hf-178m2 isomer | 1,326,000 | 17,649,060 | ||

| 16 | 天然铀(0.7% U235)用于 轻水反应堆 | 443,000 | 30%[8] | ||

| 17 | 核同质异能素Ta-180m isomer | 41,340 | 689,964 | ||

| 18 | 金属氢与氧气反应(不包括氧的质量,释放复合能,是当前释放能量最大的化学反应)[9] | 216[10] | |||

| 19 | 液氢与氧气反应(不包括氧的质量)[11] | 141.6 | |||

| 20 | 乙硼烷[12] | 78.2 | |||

| 21 | 高能燃料 | 70 | |||

| 22 | 铍与氧气反应(不包括氧的质量)[11] | 67 | |||

| 23 | 硼氢化锂 | 65.2 | 125.1 | ||

| 24 | 硼与氧气反应(不包括氧的质量)[11] | 58 | |||

| 25 | 甲烷与氧气反应(不包括氧的质量)[11] | 55 | |||

| 26 | 天然气与氧气反应(不包括氧的质量)[11] | 54 | |||

| 27 | 丁烷与氧气反应(不包括氧的质量)[11] | 48.6 | |||

| 28 | 汽油与氧气反应(不包括氧的质量)[11] | 47.3 | |||

| 29 | 煤油与氧气反应(不包括氧的质量)[11] | 46 | |||

| 30 | 石蜡与氧气反应(不包括氧的质量)[11] | 45 | |||

| 31 | 柴油与氧气反应(不包括氧的质量)[11] | 44.8 | |||

| 32 | 锂空气电池 [13] | 43.2 | |||

| 33 | 锂与氧气反应(不包括氧的质量)[11] | 43 | |||

| 34 | 取暖油与氧气反应(不包括氧的质量)[11] | 42.7 | |||

| 35 | 苯与氧气反应(不包括氧的质量)[11] | 40.2 | |||

| 36 | 生物柴油与氧气反应(不包括氧的质量)[11] | 37 | |||

| 37 | 机油与氧气反应(不包括氧的质量)[11] | 36 | |||

| 38 | 橡胶与氧气反应(不包括氧的质量)[11] | 35 | |||

| 39 | 一千克物质以7.9 km/s 的速度运动所拥有的动能[14] | 33 | |||

| 40 | 碳与氧气反应(不包括氧的质量)[11] | 32.8 | |||

| 41 | 煤与氧气反应(不包括氧的质量)[11] | 32 | |||

| 42 | 硅与氧气反应(不包括氧的质量)[11] | 32 | |||

| 43 | 石煤与氧气反应(不包括氧的质量)[11] | 31.4 | |||

| 44 | 异丙醇与氧气反应(不包括氧的质量)[11] | 30.9 | |||

| 45 | 木炭与氧气反应(不包括氧的质量)[11] | 30.1 | |||

| 46 | 铝与氧气反应(不包括氧的质量)[11] | 30 | |||

| 47 | 酒精与氧气反应(不包括氧的质量)[11] | 29.7 | |||

| 48 | 乙醇与氧气反应(不包括氧的质量)[11] | 26.9 | |||

| 49 | 镁与氧气反应(不包括氧的质量)[11] | 25.2 | |||

| 50 | 磷与氧气反应(不包括氧的质量)[11] | 25.2 | |||

| 51 | 木材与氧气反应(不包括氧的质量)[11] | 21 | |||

| 52 | 煤球与氧气反应(不包括氧的质量)[11] | 19.7 | |||

| 53 | 甲醇与氧气反应(不包括氧的质量)[11] | 19.6 | |||

| 54 | Cl2O7 + CH4 | 17.4 | |||

| 55 | 钙与氧气反应(不包括氧的质量)[11] | 15.8 | |||

| 56 | 纸与氧气反应(不包括氧的质量)[11] | 15 | |||

| 57 | 泥炭与氧气反应(不包括氧的质量)[11] | 14.7 | |||

| 58 | Cl2O7分解 | 12.2 | |||

| 59 | 硝基甲烷 | 11.3 | 12.9 | ||

| 60 | 硫与氧气反应(不包括氧的质量)[11] | 9.3 | |||

| 61 | 钠与氧气反应(不包括氧的质量)[11] | 9 | |||

| 62 | 八硝基立方烷炸药 | 8.5 | 17 | ||

| 63 | 正四面体烷炸药 | 8.3 | |||

| 64 | 七硝基立方烷炸药 | 8.2 | |||

| 65 | 煤炭与氧气反应(不包括氧的质量)[11] | 8 | |||

| 66 | Dinitroacetylene炸药 | 7.9 | |||

| 67 | 黑索金 | 7.2838 | |||

| 68 | 钠(和氯反应) | 7.0349 | |||

| 69 | 铁与氧气反应(不包括氧的质量)[11] | 7 | |||

| 70 | 四硝基立方烷炸药 | 6.95 | |||

| 71 | 铵梯铝炸药(阿芒拿尔)(Al+NH4NO3 氧化剂) | 6.9 | 12.7 | ||

| 72 | 四硝基甲烷 + 联氨推进剂 | 6.6 | |||

| 73 | 六硝基苯炸药 | 6.5 | |||

| 74 | 奥克托今 炸药 | 6.3 | |||

| 75 | 铵油炸药-ANNM(硝酸铵-硝基甲烷混合物) | 6.26 | |||

| 76 | 三硝基甲苯[15] | 4.61 | 6.92 | ||

| 77 | 铜铝热反应 (Al + CuO 氧化剂) | 4.13 | 20.9 | ||

| 78 | 铝热反应( Al粉状 + Fe2O3 氧化剂) | 4 | 18.4 | ||

| 79 | 过氧化氢分解(作为单组元推进剂) | 2.7 | 3.8 | ||

| 80 | 纳米线电池 | 2.54 | |||

| 81 | 锂电池[16] | 2.5 | |||

| 82 | 铜与氧气反应(不包括氧的质量)[11] | 2 | |||

| 83 | 水 220.64 bar, 373.8°C | 1.968 | 0.708 | ||

| 84 | 動能穿甲彈 | 1.9 | 30 | ||

| 85 | 氟离子电池(Fluoride ion Battery) | 1.7 | 2.8 | ||

| 86 | 氢闭循环燃料电池[17] | 1.62 | |||

| 87 | 肼分解(作为单组元推进剂) | 1.6 | 1.6 | ||

| 88 | 硝酸铵分解(作为单组元推进剂) | 1.4 | 2.5 | ||

| 89 | 鋰-硫電池[18] | 1.26 | 1.26 | ||

| 90 | 电容 EEStor公司生产(宣称值)[19] | 1.2 | 5.7 | 99% | 99% |

| 91 | battery, Lithium-manganese[20][21] | 1.01 | 2.09 | ||

| 92 | Thermal Energy Capacity of Molten Salt | 1 | 98%[22] | ||

| 93 | 分子弹簧 | 1 | |||

| 94 | 锂离子电池[23][24] | 0.72 | 0.9 | 95%[25] | |

| 95 | 碱性电池(长寿命设计) [23][26] | 0.59 | 1.43 | ||

| 96 | 钠-氯化镍(Na-NiCl2)电池(高温下) | 0.56 | |||

| 97 | 飞轮能量储存 | 0.5[27][28] | |||

| 98 | 氧化银电池[29] | 0.47 | 1.8 | ||

| 99 | 5.56×45 NATO子弹 | 0.4 | 3.2 | ||

| 100 | 镍氢电池,消费产品的低功率产品[30] | 0.4 | 1.55 | ||

| 101 | 溴化锌(ZnBr)电池[31] | 0.27 | |||

| 102 | 车用大功率镍氢电池 [32] | 0.25 | 0.493 | ||

| 103 | 溴钒电池 | 0.18 | 0.252 | 80%-90%[33] | |

| 104 | 镍镉电池 [23] | 0.14 | 1.08 | 80%[25] | |

| 105 | 铅酸蓄电池 [23] | 0.14 | 0.36 | ||

| 106 | 碳锌电池 [23] | 0.13 | 0.331 | ||

| 107 | 全钒氧化还原液流电池 | 0.09 | 0.1188 | 70-75% | |

| 108 | 超导磁储能 | 0.04[34] | 0.04[34] | >95% | |

| 109 | 超级电容器(Ultracapacitor) | 0.0199[35] | 0.050 | ||

| 110 | 超级电容器(Supercapacitor)(Supercapacitor) | 0.01 | 80%-98.5%[36] | 39%-70%[36] | |

| 111 | 电容器 | 0.002 [37] | |||

| 112 | 扭簧 | 0.0003 [38] | 0.0006 | ||

| 113 | 鈉-硫電池 | 1.23 | 85%[39] | ||

| 排序 | 存储形式 | 质量能量密度(MJ/kg) | 容积能量密度(MJ/L) | 峰值回收效率 % |

实际回收效率 % |

参见

参考资料

- ^ 每公斤反物质的能量密度是它自身的两倍。

- ^ [1]

- ^ 3.0 3.1 Energy density calculations of nuclear fuel. whatisnuclear.com. Retrieved 2014-04-17.

- ^ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 见核武器当量、爆炸当量

- ^ petroleum 互联网档案馆的存檔,存档日期2008-12-11.

- ^ 50% 互联网档案馆的存檔,存档日期2008-12-17.

- ^ 见热机

- ^ 见热机

- ^ 见金属氢

- ^ http://iopscience.iop.org/1742-6596/215/1/012194/pdf/1742-6596_215_1_012194.pdf

- ^ 11.00 11.01 11.02 11.03 11.04 11.05 11.06 11.07 11.08 11.09 11.10 11.11 11.12 11.13 11.14 11.15 11.16 11.17 11.18 11.19 11.20 11.21 11.22 11.23 11.24 11.25 11.26 11.27 11.28 11.29 11.30 11.31 11.32 11.33 11.34 11.35 11.36 11.37 见燃料与燃烧热

- ^ Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997), Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed) (page 164)

- ^ Girishkumar, G.; McCloskey, B.; Luntz, A. C.; Swanson, S.; Wilcke, W. Lithium−Air Battery: Promise and Challenges. The Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters. 2010, 1 (14): 2193–2203. doi:10.1021/jz1005384.

- ^ 请见各高度的切向速度(Tangential velocities at altitude)

- ^ Kinney, G.F.; K.J. Graham. Explosive shocks in air. Springer-Verlag. 1985. ISBN 3-540-15147-8.

- ^ Battery Chemistry Experience. [2009-07-25]. (原始内容存档于2011-02-24).

- ^ SCIENTISTS. [2015-03-08]. (原始内容存档于2015-04-08).

- ^ Lithium Sulfur Rechargeable Battery Data Sheet (PDF). Sion Power, Inc. 2005-09-28. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2008-08-28).

- ^ Abstract

- ^ ProCell Lithium battery chemistry. Duracell. [2009-04-21]. (原始内容存档于2009-05-23).

- ^ Properties of non-rechargeable lithium batteries. corrosion-doctors.org. [2009-04-21]. (原始内容存档于2014-04-29).

- ^ 存档副本. [2010-05-07]. (原始内容存档于2010-05-19).

- ^ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 23.4 Battery energy storage in various battery types. AllAboutBatteries.com. [2009-04-21]. (原始内容存档于2009-04-28).

- ^ A typically available lithium ion cell with an Energy Density of 201 wh/kg AA Portable Power Corp 互联网档案馆的存檔,存档日期2008-12-01.

- ^ 25.0 25.1 Justin Lemire-Elmore. The Energy Cost of Electric and Human-Powered Bicycles (PDF): 7. 2004-04-13 [2009-02-26]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2012-09-13).

Table 3: Input and Output Energy from Batteries

- ^ ProCell Alkaline battery chemistry. Duracell. [2009-04-21]. (原始内容存档于2009-04-18).

- ^ Storage Technology Report, ST6 Flywheel (PDF). [2009-07-25]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2013-01-14).

- ^ Next-gen Of Flywheel Energy Storage. Product Design & Development. [2009-05-21]. (原始内容存档于2010-07-10).

- ^ ProCell Silver Oxide battery chemistry. Duracell. [2009-04-21]. (原始内容存档于2009-12-20).

- ^ Advanced Materials for Next Generation NiMH Batteries, Ovonic, 2008 (PDF). [2009-07-25]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2010-01-04).

- ^ ZBB Energy Corp. (原始内容存档于2007-10-15).

75 to 85 watt-hours per kilogram

- ^ High Energy Metal Hydride Battery 互联网档案馆的存檔,存档日期2009-09-30.

- ^ COMPANY AND TECHNOLOGY INFORMATION SHEET 互联网档案馆的存檔,存档日期2010-11-22.

- ^ 34.0 34.1 Tixador, P. Superconducting Magnetic Energy Storage: Status and Perspective. [2]

- ^ Ultracapacitor Modules. [2009-07-25]. (原始内容存档于2008-10-08).

- ^ 36.0 36.1 F2004F193HYBRID DRIVE WITH SUPER-CAPACITOR ENERGY STORAGE 互联网档案馆的存檔,存档日期2012-07-22.

- ^ Introduction to UNIX Course Outline. [2009-07-25]. (原始内容存档于2006-10-06).

- ^ Garage Door Spring. [2009-07-25]. (原始内容存档于2008-10-13).

- ^ SciTech Connect. [2009-07-25]. (原始内容存档于2012-02-14).

外部链接

密度数据

- ^ "Aircraft Fuels." Energy, Technology and the Environment Ed. Attilio Bisio. Vol. 1. New York: John Wiley and Sons, Inc., 1995. 257–259

- "Fuels of the Future for Cars and Trucks (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)" - Dr. James J. Eberhardt - Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy, U.S. Department of Energy - 2002 Diesel Engine Emissions Reduction (DEER) Workshop San Diego, California - August 25–29, 2002

能量储存

文献

- The Inflationary Universe: The Quest for a New Theory of Cosmic Origins by Alan H. Guth (1998) ISBN 0-201-32840-2

- Cosmological Inflation and Large-Scale Structure by Andrew R. Liddle, David H. Lyth (2000) ISBN 0-521-57598-2

- Richard Becker, "Electromagnetic Fields and Interactions", Dover Publications Inc., 1964