使用者:Dkzzl/阿季奈迪恩戰役

| 穆阿維葉一世معاوية | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 倭馬亞哈里發國的第一位哈里發 | |||||

| 統治 | 661年1月 – 680年4月 | ||||

| 前任 |

| ||||

| 接任者 | 葉齊德一世 | ||||

| 敘利亞總督 | |||||

| 任期 | 639年–661年 | ||||

| 前任 | 耶齊德·本·艾比·素福彥 | ||||

| 繼任 | 停用 | ||||

| 出生 | 約597年–605年之間 麥加 | ||||

| 逝世 | 680年4月(約75-83歲) 大馬士革 | ||||

| 安葬 | 大馬士革小城門 | ||||

| 配偶 |

| ||||

| 子嗣 |

| ||||

| |||||

| 朝代 | 倭馬亞王朝 | ||||

| 父親 | 阿布·素福彥·本·哈爾卜 | ||||

| 母親 | 杏德·賓特·烏特貝 | ||||

| 宗教信仰 | 伊斯蘭教 | ||||

穆阿維葉·本·艾比·素福彥(阿拉伯語:معاوية بن أبي سفيان,羅馬化:Muʿāwiya ibn Abī Sufyān;約597、603或605年–680年4月),通稱穆阿維葉一世,是伊斯蘭史上第一個世襲哈里發王朝——倭馬亞王朝的開國之君,661年成為哈里發,一直統治到680年。他接過的是前四位「正統」哈里發的位置,後者都是伊斯蘭教先知穆罕默德的早期夥伴,而穆阿維葉直到630年後才追隨穆罕默德。

穆阿維葉與他的父親阿布·素福彥及穆罕默德同屬麥加的古萊氏部落,但他們早期都反對穆罕默德的事業,直到630年穆罕默德征服麥加後才服從。之後,穆阿維葉擔任穆罕默德的抄寫員(卡提布),後第一位哈里發阿布·伯克爾(632-634年在位)任命他為征服敘利亞的副指揮官,歐麥爾在位時(634-644年)地位不斷提高,到他的倭馬亞氏族親屬奧斯曼在位時(644-656年在位),他被任命為敘利亞(沙姆)總督。他在省內與強大的凱勒卜部落結盟,鞏固了沿海城市的防禦,並向拜占庭帝國(東羅馬帝國)發動進攻,穆斯林海軍的第一次海戰也在這一時期發生。656年奧斯曼被刺殺後,穆阿維葉宣稱要為他報仇,反對接任的哈里發阿里(656-661年在位)。隨後內戰爆發,二人的軍隊於657年在綏芬惡戰,陷入僵局,隨後一系列的仲裁與談判也沒能解決衝突。之後,穆阿維葉在敘利亞人和他的盟友,埃及征服者、總督阿姆魯·本·阿斯的支持下自稱哈里發。661年阿里遇刺而死,穆阿維葉迫使阿里之子哈桑退位,整個哈里發國都承認了穆阿維葉的權威。

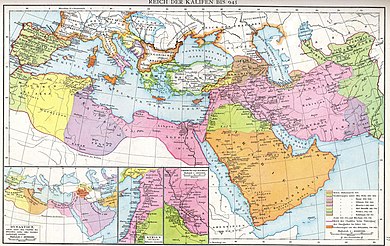

在國內,穆阿維葉主要倚靠忠於倭馬亞王朝的定居敘利亞的阿拉伯部落,並靠敘利亞以基督徒為主的官僚進行統治。他建立了負責郵政、通信與總理事務的政府部門(底萬),他也是伊斯蘭帝國中第一個在錢幣、銘文、文件上留名的哈里發。對外事務上,穆阿維葉基本每年都會派遣海軍或陸軍襲擊拜占庭帝國,674-678年,圍攻君士坦丁堡不克,然而到他統治末期戰爭局勢反而對阿拉伯人不利,使得他被迫求和。在伊拉克及東部省份,他將權力賦予強大的總督,包括穆吉雷與齊亞德·本·艾比希,還承認齊亞德是他的血親兄弟。穆阿維葉治下,將領歐格白·本·納菲於670年開始了對易弗里基葉(北非中部)的征服,東面對呼羅珊與錫斯坦的征服也得以恢復。

穆阿維葉在國內僅任命倭馬亞族人為麥地那總督,但他提名自己的兒子耶齊德為繼承人,這在伊斯蘭歷史上是前無古人的行動,主要的穆斯林領袖,包括阿里的兒子海珊與阿伊莎的親屬阿卜杜拉·本·祖拜爾都對此表示強烈反對。穆阿維葉死後,衝突最後釀成第二次穆斯林內戰。

同時代的史書對穆阿維葉抱有相當的敬意,但也批評他缺乏前幾任哈里發的虔誠與正義感,還把「公天下」轉為「家天下」。遜尼派穆斯林傳統上尊重他作為穆罕默德的同伴與《古蘭經》 抄寫員的成就,什葉派穆斯林則因他反對阿里而加以辱罵,並認為哈桑是被他毒殺的,並懷疑他皈依伊斯蘭教的信念。

出身與早年生活

[編輯]

穆阿維葉的出生時間不能確定,早期伊斯蘭史書提出了597年、603年、605年等說法[1]。他的父親阿布·素福彥·本·哈爾卜屬於麥加的古萊氏部落,是城中數一數二的大商人,經營前往敘利亞(屬拜占庭帝國)的商隊[2]。古萊氏是麥加的主要部落,穆罕默德也屬於這個部落,他與阿布·素福彥的曾祖父是一人——阿卜杜·麥納弗·本·古賽[3],但阿布·素福彥是支持多神教的阿布·沙姆氏族的領袖,並與宣揚伊斯蘭教的穆罕默德敵對[1]。穆阿維葉的母親杏德·賓特·烏特貝也屬於阿布·沙姆氏族[1]。

624年,穆罕默德與其追隨者試圖攔截阿布·素福彥帶領的,自敘利亞返回的商隊,迫使後者請求支援[4],但古萊氏的援軍在伯德爾戰役中慘敗,穆阿維葉的兄長漢扎拉(Hanzala)與外祖父烏特貝·本·賴比爾戰死[2]。阿布·素福彥接替戰死的麥加軍隊領袖阿慕爾·本·希沙姆,率軍於625年的武侯德戰役擊敗穆斯林軍隊,但627年的壕溝之戰中他圍攻麥地那不成,失去了領導地位[1]。

穆阿維葉的父親沒有參與628年麥加與穆罕默德之間侯代比亞和約的談判,次年,十五年前就已皈依伊斯蘭教的穆阿維葉寡居的姐姐烏姆·哈比巴(Umm Habiba)嫁給了穆罕默德,這一通婚可能減少了阿布·素福彥對穆罕默德的敵意,630年古萊氏的同盟違反了和約後,他曾前往麥地那與穆罕默德談判[2]。同年,穆罕默德征服麥加,穆阿維葉與父親及長兄耶齊德皈依伊斯蘭教。根據早期穆斯林史家白拉祖里以及後代史家伊本·哈哲爾·阿拉蓋斯尼引用的記載,自侯代比亞和約談判以來,穆阿維葉就已秘密皈依伊斯蘭教[1]。到632年,穆斯林的權威已擴展到整個阿拉伯半島,麥地那則成為政治中心[5],作為穆罕默德緩和與古萊氏關係計劃的一部分,穆阿維葉與其他十六位有文化的古萊氏青年一同成為先知的抄寫員(卡提布)[1],阿布·素福彥也遷居麥地那,以在新的穆斯林公社中維持自己的影響力[6]。

擔任敘利亞長官

[編輯]早期軍事生涯、行政晉升

[編輯]

632年穆罕默德去世,阿布·伯克爾接過領導重任,成為哈里發[7],他和接下來的三位哈里發歐麥爾、奧斯曼與阿里並稱「正統哈里發」,區別於穆阿維葉及其繼承者所屬的倭馬亞王朝[8]。阿布·伯克爾上任之後,當初庇護穆罕默德,並成為穆斯林的麥地那當地人——輔士挑戰他的權威,且許多之前接受伊斯蘭教的阿拉伯部落也開始叛亂,迫使他向古萊氏部落,特別是其中最強大的兩個氏族——邁赫祖姆氏族與倭馬亞所屬的阿布·沙姆氏族尋求支持以維持哈里發政權[9]。他任命幾位古萊氏成員前往鎮壓叛亂的諸部落,史稱變節者戰爭(622-623年),其中包括穆阿維葉的兄弟耶齊德。之後他又於約634年任命四位將軍前往征服敘利亞,其中包括耶齊德[10],穆阿維葉則負責指揮耶齊德的先鋒部隊[1]。阿布·素福彥本就在大馬士革附近擁有地產,通過這些任命,哈里發又讓素福彥家族在敘利亞戰爭中分得一份成果[10][註 1]。

636年,阿拉伯軍在雅爾穆克戰役中決定性地擊敗敘利亞的拜占庭軍隊,同年阿布·伯克爾的繼承者歐麥爾(634-644年在位)任命穆罕默德的重要夥伴阿布·烏拜德·本·傑拉赫為敘利亞阿拉伯軍總指揮[12],為徹底征服敘利亞奠定了基礎[13]。637年,穆阿維葉隨同歐麥爾進入耶路撒冷[1][註 2]。之後阿布·烏拜德派耶齊德於穆阿維葉前去征服西頓、貝魯特與比布魯斯[15],639年,阿布·烏拜德死於伊姆瓦斯瘟疫,歐麥爾分割了敘利亞軍隊的指揮權,耶齊德任大馬士革駐軍、約旦駐軍、巴勒斯坦駐軍指揮,資深將領伊亞德·本·甘姆任霍姆斯與賈茲拉(上美索不達米亞)長官[1][16]。當年晚些時候,耶齊德也死於瘟疫,歐麥爾任命穆阿維葉為大馬士革的軍事、財政長官(可能也包括約旦)[1][17]。640或641年,穆阿維葉攻占第一巴勒斯坦行省首府凱撒利亞,然後攻占亞實基倫,完成了穆斯林對巴勒斯坦的征服[1][18][19]。早在641或642年,穆阿維葉可能就已發動攻打奇里乞亞的戰役,一直深入到小亞細亞腹地的優海塔城[20]。644年,他又領導了攻打阿莫里烏姆的戰役[21]。

歐麥爾一向努力削減古萊氏貴族在穆斯林國家中的影響力,扶持早期皈依的穆斯林,即遷士與輔士,但阿布·素福彥兩個兒子的快速晉升似乎與此背道而馳[16]。學者萊昂內·卡塔埃尼,這一例外源於歐麥爾對倭馬亞氏族的個人尊重[17],但威爾弗雷德·馬德隆質疑這種觀點,認為歐麥爾只是缺乏選擇,敘利亞缺少能代替穆阿維葉的人物,且由於瘟疫,他無法自麥地那派遣更合適的人選[17]。

哈里發奧斯曼(屬倭馬亞氏族)即位後,巴勒斯坦被劃入穆阿維葉的管轄範圍,另一位聖伴烏邁爾·本·塞耳德·安薩里任霍姆斯-賈茲拉長官。646年末或647年初,奧斯曼又將霍姆斯-賈茲拉交給穆阿維葉統治[1],大大增加了他所能控制的軍事力量[22]。

鞏固權力

[編輯]奧斯曼在位時,穆阿維葉與敘利亞沙漠中占主導地位的凱勒卜部落結盟[23],該部落勢力範圍南到杜邁特·堅德爾盆地,北及巴爾米拉,還是遍及整個敘利亞的古達埃部落聯盟的主要部落[24][25][26]。凱勒卜部落在阿拉伯-拜占庭戰爭中基本保持中立,特別是在拜占庭帝國的首要阿拉伯盟友——信仰基督教的加薩尼王國拒絕穆斯林政府提出的倒戈請求之後,但麥地那政權也一直嘗試拉攏凱勒卜部落[27][註 3]。在伊斯蘭教進入敘利亞之前,凱勒卜部落乃至整個古達埃部落聯盟都長期受到希臘-阿拉米文化與一性論基督教影響[30][31],曾作為加薩尼王國的屬民負責保衛拜占庭帝國的敘利亞邊界,抵禦薩珊王朝與其阿拉伯代理人萊赫米王國的侵擾[30]。到穆斯林進入敘利亞時,他們已積累了豐富的戰鬥經驗,且習慣於等級秩序與軍事服從[31]。為了利用他們的力量,把敘利亞建成自己的立足點,穆阿維葉於約650年娶了凱勒卜部落酋長貝赫德爾·本·烏奈弗的女兒邁松[23][26][32],還與邁松的堂親奈伊勒·賓特·烏邁勒(Na'ila bint Umara)短暫結婚[33][註 4]。

大征服後,阿拉伯部落遷徙的主要目的地是原屬薩珊王朝的伊拉克[35],敘利亞移民相對較少,再加上瘟疫的沉重打擊與穆阿維葉重用本地阿拉伯部落的政策[35],使敘利亞的阿拉伯駐軍數量從637年的2,4萬人銳減到639年的4千人[36]。於是穆阿維葉採取了自由徵兵的政策,使得相當數量的基督徒部落民與邊疆地區的農民進入軍隊[37],,基督教的台努赫聯盟與半基半穆的泰伊部落成為北敘利亞部隊的一部分[38][39]。為了支付軍餉,穆阿維葉向哈里發請求敘利亞境內原有的拜占庭皇室土地,得到了奧斯曼的准許,這些土地肥沃、利潤豐厚,歐麥爾原本規定其為穆斯林軍隊的公共財產[40]。

敘利亞的鄉村居民——說阿拉米語的基督教農民的生活呢狀況基本沒有改變[41],但大馬士革、阿勒頗、拉塔基亞、的黎波里等城的說希臘語的城市居民紛紛逃至拜占庭帝國境內[36],留下來的人也有著親拜占庭的情感[35]。穆斯林征服一地後往往建立新的駐軍城市以容納穆斯林軍隊,實施統治,但在敘利亞,阿拉伯軍直接進入現存的城市,包括大馬士革、霍姆斯、耶路撒冷、提比里亞[36]、阿勒頗與根奈斯林[29]。穆阿維葉還修復沿海的安條克、巴爾達、塔爾圖斯、邁勒吉耶、巴尼亞斯等城,移入人口並設置駐軍[35],還命大批猶太人移入的黎波里[35]。之前薩珊王朝短暫奪取敘利亞時,曾有部分波斯人定居下來,穆阿維葉把他們遷到霍姆斯、安條克與巴勒貝克[42]。奉哈里發奧斯曼之名,穆阿維葉還安排游牧的台米木部落、阿薩德部落與蓋斯部落遷徙到幼發拉底河以北的拉卡地區[35][43]。

與拜占庭帝國的海戰、征服亞美尼亞

[編輯]穆阿維葉以的黎波里、貝魯特、提爾、阿卡、雅法等海港為基地,在東地中海數次發動海上進攻拜占庭帝國的戰役[1][37][44]。穆阿維葉首先提出渡海征服賽普勒斯的計劃,理由是該島可能成為拜占庭軍攻擊敘利亞沿海地區的基地,而且可以被阿拉伯軍輕鬆占領[45],但歐麥爾因擔心穆斯林軍隊在海上的安全而拒絕,奧斯曼一開始也拒絕了這一提議,但終於647年允許穆阿維葉發起進攻[45]。具體攻擊的年份尚不能確定,阿拉伯史料給出的時間介於647-650年之間,而在賽普勒斯索利發現的希臘文銘文提到了648-650年之間的兩次襲擊[45]。

根據9世紀史家拜拉祖里與哈里發·本·哈耶特的記載,穆阿維葉本人在他出身古萊氏奈烏法勒氏族的妻子凱特韋·賓特·蓋勒澤·本·阿卜杜·阿慕爾(Katwa bint Qaraza ibn Abd Amr)及將領烏貝德·本·薩米特的陪同下,親自指揮了這次突襲[34][45]。凱特韋死在島上,穆阿維葉又與她的姐妹菲希塔(Fakhita)結婚[34]。另一種穆斯林記載則稱是穆阿維葉的海軍將領阿卜杜拉·本·蓋斯領導,而且他還在進攻賽普勒斯島之前在薩拉米斯島登陸[44]。兩種記載都稱賽普勒斯被迫向阿拉伯人繳納與付給拜占庭政府的數額相等的貢金[44][46]。穆阿維葉在島上設置駐軍並建立了清真寺以維持哈里發政權在島上的影響力。之後雙方在島上均有勢力,都以此為基地攻擊對方的領土[46]。島上的居民很大程度上保持自治,考古證據表明,這一時期島上相當繁榮[47]。

這一時期穆阿維葉的海軍掌握著東地中海的制海權,653年,阿拉伯海軍又襲擊了克里特島與羅得島,羅得島的戰果使得穆阿維葉能交納相當多的戰利給哈里發奧斯曼[48]。644或645年,亞歷山大的埃及穆斯林海軍與敘利亞海軍發起聯合進攻,在呂基亞外海大敗拜占庭皇帝君士坦斯二世(641-668年在位)親自率領的艦隊,迫使後者逃到西西里島,史稱船桅之戰,之後阿拉伯艦隊前往進攻君士坦丁堡,沒能成功[49]。這次行動的指揮者可能是埃及總督阿卜杜拉·本·賽耳德或是穆阿維葉的副手阿布·艾阿瓦爾[49]。

之前阿拉伯人曾兩次試圖征服亞美尼亞,650年阿拉伯人的第三次進攻以穆阿維葉與拜占庭特使普羅科皮歐斯(Procopios)在大馬士革簽訂三年和平條約爾告終[50]。653年,亞美尼亞貴族狄奧多爾·厄勒什圖尼向穆阿維葉投降,拜占庭軍隊也於此年撤出亞美尼亞,承認了事實[51]。655年,穆阿維葉的副將赫比卜·本·麥斯萊麥·菲赫里攻陷狄奧多西波利斯(埃爾祖魯姆),將狄奧多爾擄回敘利亞,穩固了阿拉伯人對亞美尼亞的控制[51]。

第一次穆斯林內戰

[編輯]奧斯曼徵用伊拉克的前薩珊王室土地及其任命一批親屬任重要職位的做法[註 5]使得古萊氏族人與被剝奪權力的庫法、埃及精英開始反對他[53]。7世紀50年代,哈里發國的麥地那、埃及、庫法等地區涌動著反對哈里發奧斯曼政策的風暴,但穆阿維葉的轄區基本沒有收到影響,例外的是阿布·德爾·吉法里[1],他因公開反對奧斯曼任人唯親而被遣送到大馬士革[55],在那裡,他又批評穆阿維葉建造的豪宅過於奢侈,不久又被驅逐出境[55]。

656年6月,來自埃及的一夥不滿分子圍攻奧斯曼的住宅,迫使哈里發向穆阿維葉求援,後者派遣一支部隊前往麥地那,但在路上聽說奧斯曼已死,就退到了古拉谷[56]。穆罕默德的堂弟兼女婿阿里隨後在麥地那當選哈里發[57],穆阿維葉拒絕效忠 [58],據某些史料講,阿里還派自己的官員到敘利亞以罷免穆阿維葉,但後者不允許此人進入敘利亞[57]。學者馬德隆不認可這種說法,認為阿里上任的前七個月中,雙方並沒有正式的交流[59]。

阿里上任不久後,許多古萊氏族人都出來反對他,他們的領袖是穆罕默德的重要夥伴泰勒海與左拜爾·本·阿瓦木以及先知的遺孀阿伊莎,他們都擔心自己會在阿里治下失去影響力[60]。隨後爆發的內戰被稱為第一次「fitna」,意為「爭鬥、內戰」[註 6]。阿里在巴斯拉附近擊敗了這三位領袖,左拜爾和泰勒海戰死,阿伊莎被阿里送回麥地那,史稱駱駝之戰[60]。此後阿里穩固了自己對伊拉克、阿拉伯半島、埃及的控制,隨後將目光轉向穆阿維葉控制的敘利亞。與其他總督不同,穆阿維葉擁有強大而忠實的權力基礎,要求為他的親人奧斯曼報仇,其位置難以被輕易取代[62][63]。但在此時,穆阿維葉還沒有宣稱哈里發之位,而是把精力放在穩固敘利亞上[64][65]。

戰爭準備

[編輯]阿里在巴斯拉的勝利使穆阿維葉變得勢單力孤,其領地被埃及與伊拉克的阿里勢力包圍,而且他還需與北面的拜占庭帝國作戰[66]。657或658年,穆阿維葉首先與拜占庭皇帝簽訂和平條約,以確保北部邊境安全,集中精力準備即將到來的與阿里的戰爭[67]。他未能說服埃及總督蓋斯·本·薩阿德倒戈,於是決定放棄倭馬亞家族對埃及的征服者、前總督,涉嫌參與謀殺奧斯曼的阿慕爾·本·阿綏的敵意[68]。由於阿慕爾仍很受埃及駐軍歡迎,穆阿維葉與他簽訂協議,阿慕爾加入穆阿維葉一邊共同對抗阿里,穆阿維葉則承諾推翻埃及的阿里派總督後,任命阿慕爾為埃及終身總督[69]。

儘管強大的凱勒卜部落堅定支持穆阿維葉,但他為了鞏固對敘利亞其他地區的控制,接受了倭馬亞族人韋立德·本·烏格貝的建議,試圖穩固與希木葉爾部落、肯德部落、赫姆丹部落等組成霍姆斯駐軍的葉門(南阿拉伯)諸部落的聯盟。他重用在敘利亞聲名遠揚的肯德部落著名貴族舒勒比·本·希姆特,以匯集葉門諸部落的力量[70]。通過寬恕朱哈姆部落酋長納提爾·本·蓋斯攫取地方國庫的行為,他又獲得了這一巴勒斯坦主要部落的支持[71]。這些努力取得了成果,與阿里開戰的呼聲在穆阿維葉的領地不斷高漲[72]。阿里隨後派遣貝吉萊部落酋長賈里爾·本·阿卜杜拉(Jarir ibn Abd Allah)出使穆阿維葉,在回信中,穆阿維葉拒絕承認哈里發的合法性,實際上宣布了與阿里開戰[73]。

綏芬戰役與仲裁

[編輯]657年6月第一周,穆阿維葉與阿里的軍隊在拉卡附近的綏芬(Siffin)相遇,小規模衝突過後,雙方於19日達成一個月的休戰[74]。休戰期間,穆阿維葉派以赫比卜·本·麥斯萊麥·菲赫里為首的使團向阿里遞交最後通牒,要求他交出所謂刺殺奧斯曼的兇手,退位並召開舒拉(協商會議)決定新哈里發的人選。阿里拒絕了要求,並於7月18日宣布敘利亞人仍然頑固地拒絕承認他的權威,隨後,兩軍中的高級指揮官之間進行了持續一個星期的決鬥[75],7月26日,雙方開始大舉交戰[76]。阿里的軍隊向穆阿維葉的大營衝鋒,穆阿維葉也命敘利亞的精英部隊前進,一開始敘利亞人占了上風,打退了伊拉克軍隊,但第二天形勢逆轉,穆阿維葉一方的兩位名將戰死,即哈里發歐麥爾之子烏拜杜拉·本·歐麥爾與所謂「希木葉爾之王」祖阿勒-凱拉·塞邁費[77]。

穆阿維葉拒絕了與阿里一對一決鬥以終結仇恨的提議[78],7月28日,戰鬥達到高潮,史稱「喧囂之夜」,雙方進行了殘酷的肉搏戰,儘管兩邊傷亡都不斷增加,阿里軍還是占了絕對優勢[79][註 7]。根據史家左海里(742年去世)的記載,這種局勢使得阿慕爾·本·阿綏於次日早晨向穆阿維葉提出建議,讓士兵將《古蘭經》的篇章捆在長矛尖上,以此表示願與阿里的伊拉克軍隊談判。史家舍耳比(723年去世)則稱,阿里軍中的艾什阿斯·本·蓋斯對內戰表示擔憂,認為拜占庭人與波斯人會趁穆斯林精疲力竭時發動進攻,穆阿維葉探得這一情報後,下令士兵以長矛舉起《古蘭經》[81]。儘管這一行為某種意義上是穆阿維葉的讓步,因為他放棄了此前堅持的以武力討伐阿里,追捕藏在伊拉克的殺害奧斯曼兇手的主張,但談判也在阿里軍中播下了不和與不確定性的種子[82]。

阿里遵從自己軍中多數人的意見,接受了舉行仲裁的提議[83],他還同意了阿慕爾或穆阿維葉提出的要求,在最初的仲裁文件中放棄哈里發的主要頭銜「信士們的長官」 [84]。根據學者休·甘迺迪的說法,這使得阿里「需以平等的地位與穆阿維葉談判,放棄了他領導穆斯林社群的無可爭辯的權力」[85]。馬德隆則稱此舉讓「穆阿維葉在道義上獲勝」,引發了「阿里手下的災難性分裂」[86]。658年9月阿里返回庫法,他軍中反對仲裁的戰士大多叛逃,形成了哈瓦利吉派運動[87]。

雙方達成的初步協議決定推遲仲裁[79][88],早期穆斯林記載中關於仲裁時間、地點、結果的記載十分混亂,阿里的代表阿布·穆薩·艾什爾里與穆阿維葉的代表阿慕爾可能會面兩次,第一次在杜邁特·堅德爾舉行,第二次在烏茲盧赫舉行[89]。阿里的代表阿布·穆薩與阿慕爾不同,並不太在意他主公的成敗[90],第一次會議上,他接受了敘利亞方提出的奧斯曼死於非命的說法,這正是阿里所一直反對的問題[91],應穆阿維葉要求舉行的第二次會議在混亂中失敗了,但穆阿維葉在爭奪哈里發之位中已獲得了更大的優勢[92]。

自稱哈里發,戰爭繼續

[編輯]

談判破裂後,阿慕爾與其他代表返回大馬士革,他們稱穆阿維葉為「信士們的長官」,實際上承認了他的哈里發地位[93]。658年4月或5月,穆阿維葉接受了敘利亞人的宣誓效忠[56]。作為回應,阿里斷絕了與穆阿維葉的聯繫,重新動員軍隊,並在晨禱中詛咒穆阿維葉與其親信[93],穆阿維葉也在自己的領地內如法炮製,詛咒阿里及其親信[94]。

埃及的服從阿里的總督,阿布·伯克爾之子穆罕默德·本·阿布·伯克爾先前鎮壓了省內支持奧斯曼(反阿里)的力量,7月,穆阿維葉派阿慕爾率一支部隊前往埃及[95],打敗了總督的部隊,占領省會福斯塔特,穆罕默德被埃及反對派領袖穆阿維葉·本·胡代傑·基迪處死[95]。失去埃及嚴重打擊了阿里的威信,他本人也在與哈瓦利吉派的戰鬥中陷入困境,對巴斯拉以及伊拉克東部、南部的控制力有所下降[56][96]。儘管穆阿維葉的力量增強,但他沒有對阿里發起直接攻擊[96],而是設法賄賂支持阿里的部落首領令其倒戈,並騷擾伊拉克西部邊區的居民[96]:第一次襲擊由德赫克·本·蓋斯·菲赫里指揮,攻擊力庫法以西的沙漠中的穆斯林游牧人與朝聖者[97];第二次攻擊中,努阿曼·本·貝希爾·安薩里攻擊艾因·泰穆爾不成功;660年夏天,素福彥·本·艾烏夫成功襲擊了希特與安巴爾兩地[98]。

659或660年,穆阿維葉又向希賈茲發起攻擊,派阿卜杜拉·本·麥斯阿德·費扎里向泰馬綠洲的居民徵收慈善金並要求他們向穆阿維葉宣誓效忠,但這支部隊被庫法軍隊擊敗[99],660年4月,另一次要求麥加的古萊氏成員效忠的嘗試也告失敗[100]。

夏季,穆阿維葉派布斯爾·本·艾比·艾爾塔特率一支大軍前往征服希賈茲與葉門,他指示布斯爾在不造成傷害的情況下恐嚇麥地那居民,饒恕麥加居民,但要殺死每一個不願效忠的葉門人[101]。布斯爾相繼前往麥地那、麥加與塔伊夫,沒有受到抵抗,三城都承認了穆阿維葉的地位[102]。在葉門,布斯爾在奈季蘭及其周邊處死幾位著名人物,或是因為他們過去批評奧斯曼,也可能是因為他們與阿里有聯繫;屠殺了赫姆丹部落的許多成員以及薩那與馬里卜的市民。他本欲繼續向哈德拉毛進軍,但庫法的援軍趕到,他趕在兩軍相遇前撤退[103]。布斯爾在阿拉伯半島的征戰促使阿里的軍隊團結起來,準備進攻穆阿維葉[104],但661年1月,阿里突然遇刺而死,遠征沒有發動[105]。

哈里發生涯

[編輯]登位

[編輯]阿里死後,其子哈桑繼承了父親的權位,穆阿維葉則命德赫克·本·蓋斯·菲赫里留守敘利亞,自己率軍向庫法進軍 [106][107]。穆阿維葉賄賂了哈桑的先頭部隊指揮官烏拜杜拉·本·阿拔斯(Ubayd Allah ibn Abbas)使其遁逃,並派遣使者直接與哈桑談判[108]。最終哈桑同意退位並得到了金錢上的補償,穆阿維葉則於661年7月或9月進入庫法,被承認為哈里發。許多早期穆斯林史料稱這一年為「統一年」,並認為這是穆阿維葉哈里發任期的真正開始[56][109]。

阿里去世前後,穆阿維葉於耶路撒冷接受了一次或兩次的正式宣誓效忠,第一次在660年底或661年初舉行,第二次在661年7月舉行[110]。10世紀的耶路撒冷人地理學家麥格迪西記載道,穆阿維葉擴建了哈里發歐麥爾在聖殿山上開始的清真寺工程。即阿克薩清真寺的前身,並在那裡接受了正式效忠誓言[111]。而據現存年代最早的記載穆阿維葉在耶路撒冷即位的史料——與此事近乎同時代的一位不知名的敘利亞基督徒的撰寫的《馬龍派編年史》中的記載,穆阿維葉接受了諸部落首領的效忠,並在聖殿山附近的各各他與客西馬尼園的聖母瑪利亞之墓祈禱[112],編年史也提到,穆阿維葉「沒有像世界各地其他國王那樣戴上王冠」[113]。

治理敘利亞

[編輯]

早期穆斯林史料沒有記載多少穆阿維葉在其統治中心敘利亞施政的情況[114][115]。他在大馬士革建立了自己的宮廷,並把哈里發的國庫從庫法移到大馬士革[116]。他所依賴的主要是約有10萬人的敘利亞部落的軍隊[114][117]並通過削減伊拉克駐軍(同樣約有10萬人)的軍餉提高他們的收入[114]{sfn|Kennedy|2001|p=20}}。2千名來自古達埃聯盟與肯德部落的貴族——支持穆阿維葉的核心群體——得到了可繼承的,最高等的年金,並且被賦予了參與決定國家大事,反對或支持各種舉措的權力[30][118]。古達埃與肯德部落各自的領袖,凱勒卜部落酋長伊本·貝赫德爾和以霍姆斯為基地的舒勒比·本·希姆特,與古萊氏族人阿卜杜-拉赫曼·本·哈立德(名將哈立德·本·瓦利德之子)、德赫克·本·蓋斯·菲赫里這四人組成了穆阿維葉的敘利亞核心權力圈子[119]。

早期穆斯林史料將建立郵政(barid)、通信(rasa'il)、總理(khatam)等底萬(政府部門)的舉措歸功於穆阿維葉[30]。根據塔巴里的說法,661年一個哈瓦利吉派布勒克·本·阿卜杜拉(al-Burak ibn Abd Allah)在大馬士革的清真寺行刺穆阿維葉未遂,此後哈里發便設置了個人衛隊(赫萊斯)、精英衛隊(舒爾塔),並在清真寺中設立專屬區域(麥格蘇賴以保護自己的安全[120][121]。哈里發的國庫很大程度上依靠敘利亞的賦稅以及伊拉克、阿拉伯半島的前(薩珊)王室土地的收入,他的手下將領遠征時獲得的常規戰利品的五分之一也要上交哈里發[30]。穆阿維葉還面臨著在賈茲拉地區湧入大量游牧部落的問題,新湧入的居民包括穆達爾部落與賴比阿部落的成員、巴斯拉與庫法來的內戰難民等,根據8世紀史家賽弗·本·歐麥爾的說法,為了應對這一變化,穆阿維葉自霍姆斯駐軍區中劃分出根奈斯林駐軍區兼管賈茲拉[122][123]。但白拉祖里認為這一變化是穆阿維葉之子耶齊德一世(680-683年在位)所為[122]。

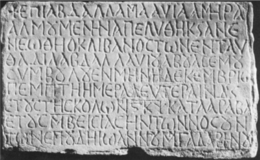

敘利亞保留了拜占庭時期的官僚系統,其工作人員主要是基督徒,包括稅收部門的首腦塞爾仲·本·曼蘇爾[124]。塞爾仲自穆阿維葉成為哈里發前就已擔任同樣的職務[125],他的父親曼蘇爾則很可能在拜占庭皇帝希拉克略(610-641年在位)手下擔任同樣的職務[124]。穆阿維葉對占敘利亞人口多數的基督徒採取了容忍的態度,給了他們至少不亞於拜占庭時期的待遇[126],因此基督教社群也對他的統治感到滿意[127]。穆阿維葉試圖鑄造他自己的貨幣,但敘利亞人拒絕使用新幣,因為上面沒有十字架的圖案[128]。穆阿維葉在敘利亞統治的唯一實物證明——一塊在太巴列湖附近的哈馬特·加德溫泉發現的663年的希臘語銘文[129]上稱哈里發為「阿卜杜拉(真主之仆)·穆阿維葉,信士們的長官」,哈里發的名字前面還有個十字架,稱讚他為了病人的福祉修復了羅馬時代的浴場。學者伊扎爾·赫希菲爾德認為,這也是「哈里發試圖取悅」基督徒的舉措[130]。哈里發經常在位於太巴列湖附近的辛納卜萊行宮過冬[131],他也曾出資修復被679年的地震毀壞的埃德薩教堂[132],還表現出對耶路撒冷的興趣[133]。儘管缺乏考古證據,中世紀文獻中的證據表明聖殿山上的一座簡陋清真寺是由穆阿維葉修建的,或者說在穆阿維葉的時代已經存在[134][註 8]。

各省治理

[編輯]穆阿維葉在國內面臨的挑戰主要是監護根基於敘利亞的中央政府,使其能重新將政治、社會上分裂的哈里發國統一起來,並確保其對組成哈里發的軍隊的各部落的權威[122]。他對組成哈里發國的各省實行間接統治,任命擁有民事、軍事全權的總督前往治理[136]。儘管原則上各地官員需要將稅收的盈餘部分交給哈里發[122],但實際上大部分盈餘都被省內的駐軍侵吞,大馬士革的中央政府只能得到微不足道的剩餘部分[30][137]。在穆阿維葉時代,地方總督的權力也依賴於各部落首領(ashraf),因為後者扮演了組成駐軍的各部落成員與官員權威之間的中間角色[122]。穆阿維葉的治國之道可能受到了他那喜歡利用自己的財富建立政治同盟的父親的影響 [137],相比直接對抗,穆阿維葉更喜歡用賄賂來解決問題。學者甘迺迪總結道,穆阿維葉的統治方式是「與各省的當權者達成合作,獎勵願意與他合作的人,與儘可能多的權貴建立關係,讓他們加入自己的事業」[137]。

伊拉克與東部

[編輯]

伊拉克是挑戰中央權威,特別挑戰穆阿維葉個人的情緒最激烈的地區。這一省份中,各部落首領(ashraf)所代表的戰爭暴發戶與正在形成的穆斯林精英見存在著巨大的矛盾,而後一群體又分裂為阿里的支持者和哈瓦利吉派[138]。穆阿維葉執政後,以阿里曾經的支持者艾什阿斯·本·蓋斯和賈里爾·本·阿卜杜拉(Jarir ibn Abd Allah)為代表的居住在庫法的部落首領們勢力逐漸強大,阿里派的胡杰爾·本·阿迪和易卜拉欣·本·艾什特爾(阿里的主要助手麥立克·艾什特爾之子)漸失權勢。661年,穆阿維葉選擇讓長期在伊拉克擔任行政、軍事職務,熟悉當地情況與各種問題的穆吉雷·本·舒阿貝擔任庫法總督。後者的任期持續了將近十年,在此期間,他維持了城中局勢的穩定,無視不危及統治的違法行為,允許庫法人繼續持有吉巴勒地區利潤豐厚的薩珊王室領地,並且與之前的總督不同,他能夠及時地支付駐軍的軍餉[139]。

在巴斯拉,穆阿維葉任命同屬阿布·沙姆氏族的親戚,還曾在奧斯曼手下任職的阿卜杜拉·本·埃米爾為總督[140]。阿卜杜拉在其任上重新開始遠征錫斯坦,最遠到達喀布爾,但巴斯拉人對遠征異國越來越不滿,使得他無法維持統治。穆阿維葉因此於664/665年將其罷免,代以齊亞德·本·艾比希[141]。阿里死時,齊亞德任法爾斯長官,他拒不承認穆阿維葉的權威,據守伊什塔克爾城不出[142],時任巴斯拉總督布斯爾曾威脅要處死他的三個兒子以逼他投降,齊亞德最終在他的師長庫法總督穆吉雷的勸說下於663年選擇服從穆阿維葉[143]。在穆阿維葉看來,齊亞德是最有能力管理巴斯拉的人[141],為了確保他的忠誠,穆阿維葉不顧兒子葉齊德以及阿卜杜拉·本·埃米爾甚至居住在希賈茲的倭馬亞族人的不滿,宣布認齊亞德為他同父異母的兄弟(齊亞德生父身份不明)[143][144]。

670年後庫法總督穆吉雷去世,穆阿維葉將庫法及其轄地交由齊亞德管轄,使他事實上成為整個哈里發國東半部的長官[141]。在任上,齊亞德解決了伊拉克的核心經濟問題,即駐軍城鎮人口過多帶來的資源短缺,方法是設法清退了一批津貼領取者,並調5萬伊拉克士兵及其家屬到呼羅珊定居。這一舉措加強了阿拉伯人在呼羅珊這一原本控制虛弱、不穩定的極東省份的力量,並有助於進一步征服河中[122]。在庫法,他還沒收了其駐軍的共有地,這些土地最終成為哈里發的財產[136]。庫法的一位人物胡杰爾·本·艾迪(Hujr ibn Adi)原本致力宣傳阿里派思想,前任總督穆吉雷容忍了他的行為[145] ,這時他又發起了反對沒收土地的運動,但被齊亞德毫不猶豫地鎮壓[122]。胡杰爾與他的隨從被送到穆阿維葉處接受懲罰,穆阿維葉對他們處以死刑,此事成為伊斯蘭歷史上第一次政治性死刑,也成為後來庫法阿里派起事的千兆[144][146]。673年齊亞德去世,之後的幾年裡,穆阿維葉逐漸將其全部總督官職授予他的兒子烏拜杜拉。通過任命穆吉雷、齊亞德及齊亞德的兒子,穆阿維葉實際也是將哈里發國東半部的管理權交給了有權勢的塞吉夫部落成員,這一族與穆阿維葉所屬的古萊氏部落長期關係密切,且在征服伊拉克中發揮了重要作用[115]。

埃及

[編輯]在埃及,與穆阿維葉合力對抗阿里的埃及征服者阿慕爾按協議繼續掌握政權,並被允許自己保留稅收的盈餘部分(常規來講要上交哈里發)[95],與其說他是哈里發的臣子,不如說他是哈里發的合伙人,這種局面持續到他於664年去世[124]。哈里發下令恢復了內戰以來中斷的埃及到麥地那的穀物與食用油運輸[147],阿慕爾死後,他先後任命自己的兄弟烏特貝·本·艾比·素福彥(664-665年在任)及穆罕默德的同伴烏格貝·本·阿米爾(665-667年在任),最後是麥斯萊麥·本·穆赫萊德為埃及總督[95][124]。麥斯萊麥得以留任到穆阿維葉去世[124],他大規模擴建了福斯塔特城及其清真寺,674年,由於亞歷山大容易遭受拜占庭帝國的海上襲擊,他還將埃及的主要海軍基地從亞歷山大轉移到福斯塔特附近的勞代島,進一步提高了這座城市的地位[148]。

阿拉伯人在埃及的主要存在基本局限於首府福斯塔特的駐軍以及亞歷山大的少量軍隊[147]。658年,阿慕爾帶來了一支敘利亞軍隊,673年,齊亞德又派來部分巴斯拉軍隊,使得福斯塔特的駐軍由1.5萬增加到4萬[147]。總督烏格貝還將亞歷山大的駐軍加到1.2萬,並在城裡建立了總督官邸。但城內的希臘裔基督徒敵視阿拉伯人的統治,烏特貝在亞歷山大的副手抱怨憑他的軍隊無法控制城市,於是穆阿維葉從敘利亞和麥地那派1.5萬人到亞歷山大[149]。與伊拉克的駐軍相比,埃及的軍人算得上安分,儘管也會有一些福斯塔特駐軍偶爾反對穆阿維葉的政策。在麥斯萊麥任上,穆阿維葉打算沒收位於法尤姆的公地,交給兒子葉齊德,激起了駐軍的大規模抗議,最終哈里發被迫收回成命[150]。

阿拉伯

[編輯]儘管為倭馬亞氏族的哈里發奧斯曼報仇是當初穆阿維葉起事爭奪哈里發之位的理由,但他既沒有效法奧斯曼賦予倭馬亞族人權力的政策,也沒有利用族人來鞏固自己的權力[137][151]。除少數例外外,倭馬亞族人基本沒有在富裕的省份或中央任職的,但多數倭馬亞族人乃至古萊氏部落的舊貴族仍在哈里發國的舊都麥地那享有權威,穆阿維葉則試圖把他們的權力限制在那裡[137][152]。The loss of political power left the Umayyads of Medina resentful toward Mu'awiya, who may have become wary of the political ambitions of the much larger Abu al-As branch of the clan—to which Uthman had belonged—under the leadership of Marwan ibn al-Hakam.[153] The caliph attempted to weaken the clan by provoking internal divisions.[154] Among the measures taken was the replacement of Marwan from the governorship of Medina in 668 with another leading Umayyad, Sa'id ibn al-As. The latter was instructed to demolish Marwan's house, but refused and when Marwan was restored in 674, he also refused Mu'awiya's order to demolish Sa'id's house.[155] Mu'awiya dismissed Marwan once more in 678, replacing him with his own nephew, al-Walid ibn Utba.[156] Besides his own clan, Mu'awiya's relations with the Banu Hashim (the clan of Muhammad and Caliph Ali), the families of Muhammad's closest companions, the once-prominent Banu Makhzum, and the Ansar was generally characterized by suspicion or outright hostility.[157]

Despite his relocation to Damascus, Mu'awiya remained fond of his original homeland and made known his longing for "the spring in Juddah [sic], the summer in Ta'if, [and] the winter in Mecca".[158] He purchased several large tracts throughout Arabia and invested considerable sums to develop the lands for agricultural use. According to the Muslim literary tradition, in the plain of Arafat and the barren valley of Mecca he dug numerous wells and canals, constructed dams and dikes to protect the soil from seasonal floods, and built fountains and reservoirs. His efforts saw extensive grain fields and date palm groves spring up across Mecca's suburbs, which remained in this state until deteriorating during the Abbasid era, which began in 750.[158] In the Yamama region in central Arabia, Mu'awiya confiscated from the Banu Hanifa the lands of Hadarim, where he employed 4,000 slaves, likely to cultivate its fields.[159] The caliph gained possession of estates in and near Ta'if which, together with the lands of his brothers Anbasa and Utba, formed a considerable cluster of properties.[160]

One of the earliest known Arabic inscriptions from Mu'awiya's reign was found at a soil-conservation dam called Sayisad 32公里(20英里) east of Ta'if, which credits Mu'awiya for the dam's construction in 677 or 678 and asks God to give him victory and strength.[161] Mu'awiya is also credited as the patron of a second dam called al-Khanaq 15公里(9.3英里) east of Medina, according to an inscription found at the site.[162] This is possibly the dam between Medina and the gold mines of the Banu Sulaym tribe attributed to Mu'awiya by the historians al-Harbi (d. 898) and al-Samhudi (d. 1533).[163]

與拜占庭帝國作戰

[編輯]

Mu'awiya possessed more personal experience than any other caliph fighting the Byzantines,[164] the principal external threat to the Caliphate,[56] and pursued the war against the Empire more energetically and continuously than his successors.[165] The First Fitna caused the Arabs to lose control over Armenia to native, pro-Byzantine princes, but in 661 Habib ibn Maslama re-invaded the region.[51] The following year, Armenia became a tributary of the Caliphate and Mu'awiya recognized the Armenian prince Grigor Mamikonian as its commander.[51] Not long after the civil war, Mu'awiya broke the truce with Byzantium,[166] and on a near-annual or bi-annual basis the caliph engaged his Syrian troops in raids across the mountainous Anatolian frontier,[124] the buffer zone between the Empire and the Caliphate.[167] At least until Abd al-Rahman ibn Khalid's death in 666, Homs served as the principal marshaling point for the offensives, and afterward Antioch served this purpose as well.[168] The bulk of the troops fighting on the Anatolian and Armenian fronts hailed from the tribal groups that arrived from Arabia during and after the conquest.[32] During his caliphate, Mu'awiya continued his past efforts to resettle and fortify the Syrian port cities.[56] Due to the reticence of Arab tribesmen to inhabit the coastlands, in 663 Mu'awiya moved Persian civilians and personnel that he had previously settled in the Syrian interior into Acre and Tyre, and transferred Asawira, elite Persian soldiers, from Kufa and Basra to the garrison at Antioch.[35][42] A few years later, Mu'awiya settled Apamea with 5,000 Slavs who had defected from the Byzantines during one of his forces' Anatolian campaigns.[35]

Based on the histories of al-Tabari (d. 923) and Agapius of Hierapolis (d. 941), the first raid of Mu'awiya's caliphate occurred in 662 or 663, during which his forces inflicted a heavy defeat on a Byzantine army with numerous patricians slain. In the next year a raid led by Busr reached Constantinople and in 664 or 665, Abd al-Rahman ibn Khalid raided Koloneia in northeastern Anatolia. In the late 660s, Mu'awiya's forces attacked Antioch of Pisidia or Antioch of Isauria.[166] Following the death of Constans II in July 668, Mu'awiya oversaw an increasingly aggressive policy of naval warfare against the Byzantines.[56] According to the early Muslim sources, raids against the Byzantines peaked between 668 and 669.[166] In each of those years there occurred six ground campaigns and a major naval campaign, the first by an Egyptian and Medinese fleet and the second by an Egyptian and Syrian fleet.[169] The culmination of the campaigns was an assault on Constantinople, but the chronologies of the Arabic, Syriac, and Byzantine sources are contradictory. The traditional view by modern historians is of a great series of naval-borne assaults against Constantinople in 約674–678, based on the history of the Byzantine chronicler Theophanes the Confessor (d. 818).[170]

However, the dating and the very historicity of this view has been challenged; the Oxford scholar James Howard-Johnston considers that no siege of Constantinople took place, and that the story was inspired by the actual siege a generation later.[171] The historian Marek Jankowiak on the other hand, in a revisionist reconstruction of the events reliant on the Arabic and Syriac sources, asserts that the assault came earlier than what is reported by Theophanes, and that the multitude of campaigns that were reported during 668–669 represented the coordinated efforts by Mu'awiya to conquer the Byzantine capital.[172] Al-Tabari reports that Mu'awiya's son Yazid led a campaign against Constantinople in 669 and Ibn Abd al-Hakam reports that the Egyptian and Syrian navies joined the assault, led by Uqba ibn Amir and Fadala ibn Ubayd respectively.[173] According to Jankowiak, Mu'awiya likely ordered the invasion during an opportunity presented by the rebellion of the Byzantine Armenian general Saborios, who formed a pact with the caliph, in spring 667. The caliph dispatched an army under Fadala, but before it could be joined by the Armenians, Saborios died. Mu'awiya then sent reinforcements led by Yazid who led the Arab army's invasion in the summer.[170] An Arab fleet reached the Sea of Marmara by autumn, while Yazid and Fadala, having raided Chalcedon through the winter, besieged Constantinople in spring 668, but due to famine and disease, lifted the siege in late June. The Arabs continued their campaigns in Constantinople's vicinity before withdrawing to Syria most likely in late 669.[174]

In 669, Mu'awiya's navy raided as far as Sicily. The following year, the wide-scale fortification of Alexandria was completed.[56] While the histories of al-Tabari and al-Baladhuri report that Mu'awiya's forces captured Rhodes in 672–674 and colonized the island for seven years before withdrawing during the reign of Yazid I, the modern historian Clifford Edmund Bosworth casts doubt on these events and holds that the island was only raided by Mu'awiya's lieutenant Junada ibn Abi Umayya al-Azdi in 679 or 680.[175] Under Emperor Constantine IV (r. 668–685), the Byzantines began a counteroffensive against the Caliphate, first raiding Egypt in 672 or 673,[176] while in winter 673, Mu'awiya's admiral Abd Allah ibn Qays led a large fleet that raided Smyrna and the coasts of Cilicia and Lycia.[177] The Byzantines landed a major victory against an Arab army and fleet led by Sufyan ibn Awf, possibly at Sillyon, in 673 or 674.[178] The next year, Abd Allah ibn Qays and Fadala landed in Crete and in 675 or 676, a Byzantine fleet assaulted Maraqiya, killing the governor of Homs.[176]

In 677, 678 or 679 Mu'awiya sued for peace with Constantine IV, possibly as a result of the destruction of his fleet or the Byzantines' deployment of the Mardaites in the Syrian littoral during that time.[179] A thirty-year treaty was concluded, obliging the Caliphate to pay an annual tribute of 3,000 gold coins, 50 horses and 30 slaves, and withdraw their troops from the forward bases they had occupied on the Byzantine coast.[180] Although the Muslims did not achieve any permanent territorial gains in Anatolia during Mu'awiya's career, the frequent raids provided Mu'awiya's Syrian troops with war spoils and tribute, which helped ensure their continued allegiance, and sharpened their combat skills.[181] Moreover, Mu'awiya's prestige was boosted and the Byzantines were precluded from any concerted campaigns against Syria.[182]

征服北非中部

[編輯]

Although the Arabs had not advanced beyond Cyrenaica since the 640s other than periodic raids, the expeditions against Byzantine North Africa were renewed during Mu'awiya's reign.[183] In 665 or 666 Ibn Hudayj led an army which raided Byzacena (southern district of Byzantine Africa) and Gabes and temporarily captured Bizerte before withdrawing to Egypt. The following year Mu'awiya dispatched Fadala and Ruwayfi ibn Thabit to raid the commercially valuable island of Djerba.[184] Meanwhile, in 662 or 667, Uqba ibn Nafi, a Qurayshite commander who had played a key role in the Arabs' capture of Cyrenaica in 641, reasserted Muslim influence in the Fezzan region, capturing the Zawila oasis and the Garamantes capital of Germa.[185] He may have raided as far south as Kawar in modern-day Niger.[185]

The struggle over the succession of Constantine IV drew Byzantine focus away from the African front.[186] In 670, Mu'awiya appointed Uqba as Egypt's deputy governor over the North African lands under Arab control west of Egypt. At the head of a 10,000-strong force, Uqba commenced his expedition against the territories west of Cyrenaica.[187] As he advanced, his army was joined by Islamized Luwata Berbers and their combined forces conquered Ghadamis, Gafsa and the Jarid.[185][187] In the last region he established a permanent Arab garrison town called Kairouan, at a relatively safe distance from Carthage and the coastal areas, which had remained under Byzantine control, to serve as a base for further expeditions. It also aided Muslim conversion efforts among the Berber tribes that dominated the surrounding countryside.[188]

Mu'awiya dismissed Uqba in 673, probably out of concern that he would form an independent power base in the lucrative regions that he had conquered. The new Arab province, Ifriqiya (modern-day Tunisia), remained subordinate to the governor of Egypt, who sent his mawla (non-Arab, Muslim freedman) Abu al-Muhajir Dinar to replace Uqba, who was arrested and transferred to Mu'awiya's custody in Damascus. Abu al-Muhajir continued the westward campaigns as far as Tlemcen and defeated the Awraba Berber chief Kasila, who subsequently embraced Islam and joined his forces.[188] In 678, a treaty between the Arabs and the Byzantines ceded Byzacena to the Caliphate, while forcing the Arabs to withdraw from the northern parts of the province.[186] After Mu'awiya's death, his successor Yazid reappointed Uqba, Kasila defected and a Byzantine–Berber alliance ended Arab control over Ifriqiya,[188] which was not reestablished until the reign of Caliph Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan (r. 685–705).[189]

提名耶齊德為繼承人

[編輯]In a move unprecedented in Islamic politics, Mu'awiya nominated his own son, Yazid, as his successor.[190] The caliph likely held ambitions for his son's succession over a considerable period.[191] In 666, he allegedly had his governor in Homs, Abd al-Rahman ibn Khalid, poisoned to remove him as a potential rival to Yazid.[192] The Syrian Arabs, with whom Abd al-Rahman ibn Khalid was popular, had viewed the governor as the caliph's most suitable successor by dint of his military record and descent from Khalid ibn al-Walid.[193][註 9]

It was not until the latter half of his reign that Mu'awiya publicly declared Yazid heir apparent, though the early Muslim sources offer divergent details about the timing and location of the events relating to the decision.[199] The accounts of al-Mada'ini (752–843) and Ibn al-Athir (1160–1232) agree that al-Mughira was the first to suggest that Yazid be acknowledged as Mu'awiya's successor and that Ziyad supported the nomination with the caveat that Yazid abandon impious activities which could arouse opposition from the Muslim polity.[200] According to al-Tabari, Mu'awiya publicly announced his decision in 675 or 676 and demanded oaths of allegiance be given to Yazid.[201] Ibn al-Athir alone relates that delegations from all the provinces were summoned to Damascus where Mu'awiya lectured them on his rights as ruler, their duties as subjects and Yazid's worthy qualities, which was followed by the calls of al-Dahhak ibn Qays and other courtiers that Yazid be recognized as the caliph's successor. The delegates lent their support, with the exception of the senior Basran nobleman al-Ahnaf ibn Qays, who was ultimately bribed into compliance.[202] Al-Mas'udi (896–956) and al-Tabari do not mention provincial delegations other than a Basran embassy led by Ubayd Allah ibn Ziyad in 678–679 or 679–680, respectively, which recognized Yazid.[203]

According to Hinds, in addition to Yazid's nobility, age and sound judgement, "most important of all" was his connection to the Kalb. The Kalb-led Quda'a confederation was the foundation of Sufyanid rule and Yazid's succession signaled the continuation of this alliance.[30] In nominating Yazid, the son of the Kalbite Maysun, Mu'awiya bypassed his older son Abd Allah from his Qurayshite wife Fakhita.[204] Alhough support from the Kalb and the Quda'a was guaranteed, Mu'awiya exhorted Yazid to widen his tribal support base in Syria. As the Qaysites were the predominant element in the northern frontier armies, Mu'awiya's appointment of Yazid to lead the war efforts with Byzantium may have served to foster Qaysite support for his nomination.[205] Mu'awiya's efforts to that end were not entirely successful as reflected in a line by a Qaysite poet: "we will never pay allegiance to the son of a Kalbi woman [i.e. Yazid]".[206][207]

In Medina, Mu'awiya's distant kinsmen Marwan ibn al-Hakam, Sa'id ibn al-As and Ibn Amir accepted Mu'awiya's succession order, albeit disapprovingly.[208] Most opponents of Mu'awiya's order in Iraq and among the Umayyads and Quraysh of the Hejaz were ultimately threatened or bribed into acceptance.[181] The remaining principle opposition emanated from Husayn ibn Ali, Abd Allah ibn al-Zubayr, Abd Allah ibn Umar and Abd al-Rahman ibn Abi Bakr, all prominent Medina-based sons of earlier caliphs or close companions of Muhammad.[209] As they possessed the nearest claims to the caliphate, Mu'awiya was determined to obtain their recognition.[210][211] According to the historian Awana ibn al-Hakam (d. 764), before his death, Mu'awiya ordered certain measures to be taken against them, entrusting these tasks to his loyalists al-Dahhak ibn Qays and Muslim ibn Uqba.[212]

去世

[編輯]Mu'awiya died from an illness in Damascus in Rajab 60 AH (April or May 680 CE), at around the age of 80.[1][213] The medieval accounts vary regarding the specific date of his death, with Hisham ibn al-Kalbi (d. 819) placing it on 7 April, al-Waqidi on 21 April and al-Mada'ini on 29 April.[214] Yazid, who was away from Damascus at the time of his father's death,[215] is held by Abu Mikhnaf (d. 774) to have succeeded him on 7 April, while the Nestorian chronicler Elias of Nisibis (d. 1046) says it occurred on 21 April.[216] In his last testament, Mu'awiya told his family "Fear God, Almighty and Great, for God, praise Him, protects whoever fears Him, and there is no protector for one who does not fear God".[217] He was buried next to the Bab al-Saghir gate of the city and the funeral prayers were led by al-Dahhak ibn Qays, who mourned Mu'awiya as the "stick of the Arabs and the blade of the Arabs, by means of whom God, Almighty and Great, cut off strife, whom He made sovereign over mankind, by means of whom he conquered countries, but now he has died".[218]

Mu'awiya's grave was a visitation site as late as the 10th century. Al-Mas'udi holds that a mausoleum was built over the grave and was open to visitors on Mondays and Thursdays. Ibn Taghribirdi asserts that Ahmad ibn Tulun, the autonomous 9th-century ruler of Egypt and Syria, erected a structure on the grave in 883 or 884 and employed members of the public to regularly recite the Qur'an and light candles around the tomb.[219]

評價與影響

[編輯]

Like Uthman, Mu'awiya adopted the title khalifat Allah ('deputy of God'), instead of khalifat rasul Allah ('deputy of the messenger of God'), the title used by the other caliphs who preceded him.[220] The title may have implied political as well as religious authority and divine sanctioning.[30] He is reported by al-Baladhuri to have said "The earth belongs to God and I am the deputy of God".[221] Nevertheless, whatever the absolutist connotations the title may have had, Mu'awiya evidently did not impose this religious authority. Instead, he governed indirectly like a supra-tribal chief using alliances with provincial ashraf, his personal skills, persuasive power, and wit.[30][222]

Apart from his war with Ali, he did not deploy his Syrian troops domestically, and often used monetary gifts as a tool to avoid conflict.[137] In Julius Wellhausen's assessment, Mu'awiya was an accomplished diplomat "allowing matters to ripen of themselves, and only now and then assisting their progress".[223] He further states that Mu'awiya had the ability to identify and employ the most talented men at his service and made even those whom he distrusted work for him.[223]

In the view of the historian Patricia Crone, Mu'awiya's successful rule was facilitated by the tribal composition of Syria. There, the Arabs who formed his support base were distributed throughout the countryside and were dominated by a single confederation, the Quda'a. This was in contrast to Iraq and Egypt, where the diverse tribal composition of the garrison towns meant that the government had no cohesive support base and had to create a delicate balance between the opposing tribal groups. As evidenced by the disintegration of Ali's Iraqi alliance, maintaining this balance was untenable. In her view, Mu'awiya's taking advantage of the tribal circumstances in Syria prevented the dissolution of the Caliphate in the civil war.[224] In the words of the orientalist Martin Hinds, the success of Mu'awiya's style of governance is "attested by the fact that he managed to hold his kingdom together without ever having to resort to using his Syrian troops".[30]

In the long-term, Mu'awiya's system proved precarious and unviable.[30] Reliance on personal relations meant his government was dependent on paying and pleasing its agents instead of commanding them. This created a "system of indulgence", according to Crone.[225] The governors became increasingly unaccountable and amassed personal wealth. The tribal balance on which he relied was insecure and a slight fluctuation would lead to factionalism and infighting.[225] When Yazid became caliph, he continued his father's model. Controversial as his nomination had been, he had to face the rebellions of Husayn and Ibn al-Zubayr. Although he was able to defeat them with the help of his governors and the Syrian army, the system fractured as soon as he died in November 683. The provincial ashraf defected to Ibn al-Zubayr, as did the Qaysite tribes, who had migrated to Syria during Mu'awiya's reign and were opposed to the Quda'a confederation on whom Sufyanid power rested. In a matter of months the authority of Yazid's successor, Mu'awiya II, was restricted to Damascus and its environs. Although the Umayyads, backed by the Quda'a, were able to reconquer the Caliphate after the decade-long second civil war, it was under the leadership of Marwan, founder of the new ruling Umayyad house, the Marwanids, and his son Abd al-Malik.[226] Having realized the weakness of Mu'awiya's model and lacking in his political skill, the Marwanids abandoned his system in favor of a more traditional form of governance where the caliph was the central authority.[227] Nonetheless, the hereditary succession introduced by Mu'awiya became a permanent feature of many of the Muslim governments that followed.[228]

Kennedy views the preservation of the Caliphate's unity as Mu'awiya's greatest achievement.[229] Expressing a similar viewpoint, Mu'awiya's biographer R. Stephen Humphreys states that although maintaining the integrity of the Caliphate would have been an achievement on its own, Mu'awiya was intent on vigorously continuing the conquests that had been initiated by Abu Bakr and Umar. By creating a formidable navy, he made the Caliphate the dominant force in the eastern Mediterranean and the Aegean. Control of northeastern Iran was secured and the Caliphate's frontier was expanded in North Africa.[230] Madelung deems Mu'awiya a corruptor of the caliphal office, under whom the precedence in Islam (sabiqa), which was the determining factor in the choice of earlier caliphs, gave way to the might of the sword, the people became his subjects and he became the "absolute lord over their life and death".[231] He strangled the communal spirit of Islam and used the religion as a tool of "social control, exploitation and military terrorization".[231]

Mu'awiya was the first caliph whose name appeared on coins, inscriptions, or documents of the nascent Islamic empire.[232] The inscriptions from his reign lacked any explicit reference to Islam or Muhammad and the only titles that appear are 'servant of God' and 'commander of the faithful'. This has led some modern historians to question Mu'awiya's commitment to Islam.[註 10] They have proposed that he adhered to a non-confessional or indeterminate form of monotheism, or may have been a Christian. Asserting that the earliest Muslims did not see their faith as different from other monotheistic faiths, these historians see the earlier Medina-based caliphs in the same vein, but no public proclamations from their period exist. On the other hand, the historian Robert Hoyland notes that Mu'awiya gave a very Islamic challenge to the Byzantine emperor Constans to "deny [the divinity of] Jesus and turn to the Great God who I worship, the God of our father Abraham" and speculates that Mu'awiya's tour of Christian sites in Jerusalem was done to demonstrate "the fact that he, and not the Byzantine emperor, was now God's representative on earth".[234]

早期歷史記載

[編輯]The surviving Muslim histories originated in Abbasid-era Iraq.[235] The compilers, the narrators from whom the stories were collected, and the overall public sentiment in Iraq were hostile to the Syria-based Umayyads,[236] under whom Syria was a privileged province and Iraq was locally perceived as a Syrian colony.[228] Moreover, the Abbasids, having overthrown the Umayyads in 750, saw them as illegitimate rulers and further tarnished their memory to enhance their own legitimacy. Abbasid caliphs like al-Saffah, al-Ma'mun, and al-Mu'tadid publicly condemned Mu'awiya and other Umayyad caliphs.[237] As such, the Muslim historical tradition is by and large anti-Umayyad.[235] Nonetheless, in the case of Mu'awiya it portrays him in a relatively balanced manner.[238]

On the one hand, it portrays him as a successful ruler who implemented his will with persuasion instead of force.[238] It stresses his quality of hilm, which in his case meant mildness, slowness to anger, subtlety, and management of people by perceiving their needs and desires.[30][239] The historical tradition is rife with anecdotes of his political acumen and self-control. In one such anecdote, when inquired about allowing one of his courtiers to address him with arrogance, he remarked:[240]

I do not insert myself between the people and their tongue, so long as they do not insert themselves between us and our sovereignty.[240]

The tradition presents him operating in the way of a traditional tribal sheikh who lacks absolute authority; summoning delegations (wufud) of tribal chiefs, and persuading them with flattery, arguments, and presents. This is exemplified in a saying attributed to him: "I never use my voice if I can use my money, never my whip if I can use my voice, never my sword if I can use my whip; but, if I have to use my sword, I will."[238]

On the other hand, the tradition also portrays him as a despot who perverted the caliphate into kingship. In the words of al-Ya'qubi (d. 898):[238]

[Mu'awiya] was the first to have a bodyguard, police-force and chamberlains ... He had somebody walk in front of him with a spear, took alms out of the stipends and sat on a throne with the people below him ... He used forced labour for his building projects ... He was the first to turn this matter [the caliphate] into mere kingship.[241]

Al-Baladhuri calls him the 'Khosrow of the Arabs' (kisra l-'arab).[242] 'Khosrow' was used by the Arabs as a reference to Sasanian Persian monarchs in general, who the Arabs associated with worldly splendor and authoritarianism, as opposed to the humility of Muhammad.[243] Mu'awiya was compared to these monarchs mainly because he appointed his son Yazid as the next caliph, which was viewed as a violation of the Islamic principle of shura and an introduction of dynastic rule on par with the Byzantines and Sasanians.[238][242] The civil war that erupted after Mu'awiya's death is asserted to have been the direct consequence of Yazid's nomination.[238] In the Islamic tradition, Mu'awiya and the Umayyads are given the title of malik (king) instead of khalifa (caliph), though the succeeding Abbasids are recognized as caliphs.[244]

The contemporary non-Muslim sources generally present a benign image of Mu'awiya.[126][238] The Greek historian Theophanes calls him a protosymboulos, 'first among equals'.[238] According to Kennedy, the Nestorian Christian chronicler John bar Penkaye writing in the 690s "has nothing but praise for the first Umayyad caliph ... of whose reign he says 'the peace throughout the world was such that we have never heard, either from our fathers or from our grandparents, or seen that there had ever been any like it'".[245]

穆斯林觀點

[編輯]In contrast to the four earlier caliphs, who are considered as models of piety and having governed with justice, Mu'awiya is not recognized as a rightly-guided caliph (khalifa al-rashid) by the Sunnis.[241] He is seen as transforming the caliphate into a worldly and despotic kingship. His acquisition of the caliphate through the civil war and his institution of the hereditary succession by appointing his son Yazid as heir apparent are the principal charges made against him.[246] Although Uthman and Ali had been highly controversial during the early period, religious scholars in the 8th and 9th centuries compromised in order to appease and absorb the Uthmanid and pro-Alid factions. Uthman and Ali were thus regarded along with the first two caliphs as divinely guided, whereas Mu'awiya and those who came after him were viewed as oppressive tyrants.[241] Nevertheless, the Sunnis accord him the status of a companion of Muhammad and consider him a scribe of the Qur'anic revelation (katib al-wahi). On these accounts, he is also respected.[247][248] Some Sunnis defend his war against Ali holding that although he was in error, he acted according to his best judgment and had no evil intentions.[249]

Mu'awiya's war with Ali, whom the Shia hold as the true successor of Muhammad, has made him a reviled figure in Shia Islam. According to the Shia, based on this alone Mu'awiya qualifies as an unbeliever, if he was a believer to begin with.[248] In addition, he is held responsible for the killing of a number of Muhammad's companions at Siffin, having ordered the cursing of Ali from the pulpit, appointing Yazid as his successor, who went on to kill Husayn at Karbala, executing the pro-Alid Kufan nobleman Hujr ibn Adi,[250] and assassinating Hasan by poisoning.[251] As such, he has been a particular target of Shia traditions. Some traditions hold him to have been born of an illegitimate relationship between Abu Sufyan's wife Hind and Muhammad's uncle Abbas.[252] His conversion to Islam is held to be devoid of any conviction and to have been motivated by convenience after Muhammad conquered Mecca. On this basis he is given the title of taliq (freed slave of Muhammad). A number of hadiths are ascribed to Muhammad condemning Mu'awiya and his father Abu Sufyan in which he is called "an accursed man (la'in) son of an accursed man" and prophesying that he will die as an unbeliever.[253] Unlike the Sunnis, the Shia deny him the status of a companion[253] and also refute the Sunni claims that he was a scribe of the Qur'anic revelation.[248] Like other opponents of Ali, Mu'awiya is cursed in a ritual called tabarra, which is held by many Shia to be an obligation.[254]

Amid rising religious sectarianism among Muslims in the 10th century, while the Abbasid Caliphate was dominated by the Twelver Shia emirs of the Buyid dynasty, the figure of Mu'awiya became a propaganda tool used by the Shia and the Sunnis opposed to them. Strong pro-Mu'awiya sentiments were voiced by Sunnis in several Abbasid cities, including Baghdad, Wasit, Raqqa and Isfahan. At about the same time, the Shia were permitted by the Buyids and the Sunni Abbasid caliphs to perform the ritual cursing of Mu'awiya in mosques.[255] In 10th–11th-century Egypt, the figure of Mu'awiya occasionally played a similar role, with the Ismaili Shia Fatimid caliphs introducing measures opposed to Mu'awiya's memory and opponents of the government using him as a tool to berate the Shia.[256]

注釋

[編輯]- ^ 據拜拉祖里記載,阿布·素福彥在巴爾蓋高地擁有一個村莊,後成為大馬士革駐軍區的一部分 ,13世紀敘利亞地理學者雅古特認為該村名叫比吉尼斯(Biqinis)[11]

- ^ 1968年一份阿拉伯文文獻在聖殿山的西南部被發現,標明日期為652年,作者為「穆阿維葉」,可能就是本文中的穆阿維葉。銘文共有九行,只有部分可讀;學者摩西·沙龍認為其內容與637年穆斯林攻占耶路撒冷有關,因為其中提到 阿布·烏拜德·本·傑拉赫與阿卜杜-拉赫曼·本·艾烏夫這兩位傳統上認為與此事有關的聖伴。這份文件寫於阿布·烏拜德死後數年,並與阿卜杜-拉赫曼的死亡時間粗略相符,但與本是抄寫員的穆阿維葉擔任總督的時間相符。沙龍因此認為這份文件是穆阿維葉寫的紀年該城投降的法律文件[14]。

- ^ 學者哈里里·阿薩米納(Khalil Athamina)認為,哈里發歐麥爾嘗試讓敘利亞本地的阿拉伯部落成為抵禦拜占庭帝國反攻的中堅力量,於是於解除了哈立德·本·瓦利德的敘利亞軍隊總指揮職務,並讓哈立德軍中諸部落撤回伊拉克,因為他們可能被凱勒卜部落及其盟友視為威脅[28]。古萊氏族人與早期的穆斯林貴族則尋求確保控制他們長期以來很熟悉的敘利亞,因而鼓勵後皈依的游牧部落遷徙至伊拉克[29]。學者威爾弗雷德·馬德隆則認為,歐麥爾重用耶齊德與穆阿維葉兩兄弟是為了確保哈里發政權在敘利亞的權威,對抗在穆斯林征服中發揮作用,並「強大而很有野心」的南阿拉伯人——舊希木葉爾王國貴族[17]。

- ^ 奈伊勒與穆阿維葉離婚後,又嫁給穆阿維葉的親密助手赫比卜·本·麥斯萊麥·菲赫里,後者去世後,又嫁給穆阿維葉的另一位親密下屬努阿曼·本·貝希爾·安薩里[34]。

- ^ 奧斯曼試圖維持古萊氏對哈里發政權的控制,改變歐麥爾的相對鬆散的財政政策[52][53]。他把所有重要的總督職位都分給屬於倭馬亞氏族及其上級氏族阿布·沙姆氏族的近親:族弟穆阿維葉在敘利亞、賈茲拉任職,庫法先後由倭馬亞族人韋立德·本·烏格貝與賽義德·本·阿斯管理,巴斯拉與巴林(東阿拉伯)、阿曼由奧斯曼的堂弟阿卜杜拉·本·埃米爾統治,阿布·沙姆氏族的阿里·本·艾迪·本·賴比厄(Ali ibn Adi ibn Rabi'a)統治麥加,義弟阿卜杜拉·本·賽耳德任埃及總督,另外哈里發的堂弟麥爾萬·本·赫凱姆在中央政府中也有很大權力[54]。奧斯曼還要求被征服地區土地的盈餘收入要交給中央政府,這些土地雖已被歐麥爾宣布為國有土地,但實際受諸部落的控制。他還將部分土地授予親戚和其他著名的古萊氏成員[53]。

- ^ 歷史方面,fitna意為一場導致統一的穆斯林社會內部出現裂痕,危及信仰的內戰或叛亂[61]。

- ^ The consensus in the early Muslim sources holds that Caliph Ali's Iraqi forces gained the advantage during the battle prompting the Syrians to appeal for a settlement by arbitration. This is contrasted by a number of early non-Muslim sources, including Theophanes the Confessor, according to whom the Syrians were victorious, an assertion supported by Umayyad court poetry.[56][80]。

- ^ 基督教朝聖者阿爾庫勒夫於679-681年間到訪耶路撒冷,指出聖殿山上建起了一座臨時的穆斯林祈禱室,以木樑與黏土製造,可容納3千名信徒;而一部猶太人的米德拉什宣稱穆阿維葉重建了聖殿山的圍牆;10世紀中期的穆斯林史家穆特赫爾·本·塔希爾·麥格迪西(al-Mutahhar ibn Tahir al-Maqdisi)明確指出穆阿維葉修建了一座清真寺[135]。

- ^ The claim that Mu'awiya had Abd al-Rahman ibn Khalid poisoned by his Christian doctor Ibn Uthal is found in the medieval Islamic histories of al-Mada'ini, al-Tabari, al-Baladhuri and Mus'ab al-Zubayri, among others[194][195] and is accepted by historian Wilferd Madelung,[194] while historians Martin Hinds and Julius Wellhausen consider Mu'awiya's role in the affair as an allegation of the early Muslim sources.[195][196] The Orientalists Michael Jan de Goeje and Henri Lammens dismiss the claim;[197][198] the former called it an "absurdity" and "incredible" that Mu'awiya "would have deprived himself of one of his best men" and the more likely scenario was that Abd al-Rahman ibn Khalid had been ill and Mu'awiya attempted to have him treated by Ibn Uthal, who was unsuccessful. De Goeje further doubts the credibility of the reports as they originated in Medina, the home of his Banu Makhzum clan, rather than Homs where Abd al-Rahman ibn Khalid had died.[197]

- ^ These include Fred M. Donner, Yehuda D. Nevo, Karl-Heinz Ohlig, and Gerd R. Puin.[233]

引用

[編輯]- ^ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 Hinds 1993,第264頁.

- ^ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Watt 1960a,第151頁.

- ^ Hawting 2000,第21–22頁.

- ^ Watt 1960b,第868頁.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927,第22–23頁.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927,第20–21頁.

- ^ Lewis 2002,第49頁.

- ^ Kennedy 2004,第52頁.

- ^ Kennedy 2004,第54頁.

- ^ 10.0 10.1 Madelung 1997,第45頁.

- ^ Fowden 2004,第151, note 54頁.

- ^ Athamina 1994,第259頁.

- ^ Donner 2014,第133–134頁.

- ^ Sharon 2018,第100–101, 108–109頁.

- ^ Donner 2014,第154頁.

- ^ 16.0 16.1 Madelung 1997,第60–61頁.

- ^ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 Madelung 1997,第61頁.

- ^ Donner 2014,第153頁.

- ^ Sourdel 1965,第911頁.

- ^ Kaegi 1995,第67, 246頁.

- ^ Kaegi 1995,第245頁.

- ^ Donner 2012,第152頁.

- ^ 23.0 23.1 Dixon 1978,第493頁.

- ^ Lammens 1960,第920頁.

- ^ Donner 2014,第106頁.

- ^ 26.0 26.1 Marsham 2013,第104頁.

- ^ Athamina 1994,第263頁.

- ^ Athamina 1994,第262, 265–268頁.

- ^ 29.0 29.1 Kennedy 2007,第95頁.

- ^ 30.00 30.01 30.02 30.03 30.04 30.05 30.06 30.07 30.08 30.09 30.10 30.11 Hinds 1993,第267頁.

- ^ 31.0 31.1 Wellhausen 1927,第55, 132頁.

- ^ 32.0 32.1 Humphreys 2006,第61頁.

- ^ Morony 1987,第215頁.

- ^ 34.0 34.1 34.2 Morony 1987,第215–216頁.

- ^ 35.0 35.1 35.2 35.3 35.4 35.5 35.6 35.7 Jandora 1986,第111頁.

- ^ 36.0 36.1 36.2 Donner 2014,第245頁.

- ^ 37.0 37.1 Jandora 1986,第112頁.

- ^ Shahid 2000a,第191頁.

- ^ Shahid 2000b,第403頁.

- ^ Madelung 1997,第82頁.

- ^ Donner 2014,第248–249頁.

- ^ 42.0 42.1 Kennedy 2001,第12頁.

- ^ Donner 2014,第248頁.

- ^ 44.0 44.1 44.2 Bosworth 1996,第157頁.

- ^ 45.0 45.1 45.2 45.3 Lynch 2016,第539頁.

- ^ 46.0 46.1 Lynch 2016,第540頁.

- ^ Lynch 2016,第541–542頁.

- ^ Bosworth 1996,第158頁.

- ^ 49.0 49.1 Bosworth 1996,第157–158頁.

- ^ Kaegi 1995,第184–185頁.

- ^ 51.0 51.1 51.2 51.3 Kaegi 1995,第185頁.

- ^ Kennedy 2004,第70頁.

- ^ 53.0 53.1 53.2 Donner 2012,第152–153頁.

- ^ Madelung 1997,第86–87頁.

- ^ 55.0 55.1 Madelung 1997,第84頁.

- ^ 56.0 56.1 56.2 56.3 56.4 56.5 56.6 56.7 56.8 Hinds 1993,第265頁.

- ^ 57.0 57.1 Lewis 2002,第62頁.

- ^ Humphreys 2006,第74頁.

- ^ Madelung 1997,第184頁.

- ^ 60.0 60.1 Hawting 2000,第27頁.

- ^ Gardet 1965,第930頁.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927,第55–56, 76頁.

- ^ Kennedy 2004,第76頁.

- ^ Humphreys 2006,第77頁.

- ^ Hawting 2000,第28頁.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927,第76頁.

- ^ Shaban 1976,第74頁.

- ^ Madelung 1997,第191, 196頁.

- ^ Madelung 1997,第196–197頁.

- ^ Madelung 1997,第199–200頁.

- ^ Madelung 1997,第224頁.

- ^ Madelung 1997,第203頁.

- ^ Madelung 1997,第204–205頁.

- ^ Madelung 1997,第225–226, 229頁.

- ^ Madelung 1997,第230–231頁.

- ^ Lewis 2002,第63頁.

- ^ Madelung 1997,第232–233頁.

- ^ Madelung 1997,第235頁.

- ^ 79.0 79.1 Vaglieri 1960,第383頁.

- ^ Crone 2003,第203, note 30頁.

- ^ Hinds 1972,第93–94頁.

- ^ Madelung 1997,第238頁.

- ^ Hinds 1972,第98頁.

- ^ Hinds 1972,第100頁.

- ^ Kennedy 2004,第79頁.

- ^ Madelung 1997,第245頁.

- ^ Donner 2012,第162頁.

- ^ Hinds 1972,第101頁.

- ^ Madelung 1997,第254–255頁.

- ^ Hinds 1972,第99頁.

- ^ Donner 2012,第162–163頁.

- ^ Donner 2012,第165頁.

- ^ 93.0 93.1 Madelung 1997,第257頁.

- ^ Madelung 1997,第258頁.

- ^ 95.0 95.1 95.2 95.3 Kennedy 1998,第69頁.

- ^ 96.0 96.1 96.2 Wellhausen 1927,第99頁.

- ^ Madelung 1997,第262–263, 287頁.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927,第100頁.

- ^ Madelung 1997,第289頁.

- ^ Madelung 1997,第290–292頁.

- ^ Madelung 1997,第299–300頁.

- ^ Madelung 1997,第301–303頁.

- ^ Madelung 1997,第304–305頁.

- ^ Madelung 1997,第307頁.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927,第102–103頁.

- ^ Donner 2012,第166頁.

- ^ Madelung 1997,第317頁.

- ^ Madelung 1997,第320, 322頁.

- ^ Marsham 2013,第93頁.

- ^ Marsham 2013,第96頁.

- ^ Marsham 2013,第97, 100頁.

- ^ Marsham 2013,第87, 89, 101頁.

- ^ Marsham 2013,第94, 106頁.

- ^ 114.0 114.1 114.2 Wellhausen 1927,第131頁.

- ^ 115.0 115.1 Kennedy 2004,第86頁.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927,第59–60, 131頁.

- ^ Kennedy 2001,第20頁.

- ^ Crone 1994,第44頁.

- ^ Kennedy 2004,第86–87頁.

- ^ Hawting 1996,第223頁.

- ^ Kennedy 2001,第13頁.

- ^ 122.0 122.1 122.2 122.3 122.4 122.5 122.6 Hinds 1993,第266頁.

- ^ Crone 1994,第45, note 239頁.

- ^ 124.0 124.1 124.2 124.3 124.4 124.5 Kennedy 2004,第87頁.

- ^ Sprengling 1939,第182頁.

- ^ 126.0 126.1 Humphreys 2006,第102–103頁.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927,第134頁.

- ^ Hawting 2000,第842頁.

- ^ Foss 2016,第83頁.

- ^ Hirschfeld 1987,第107頁.

- ^ Hasson 1982,第99頁.

- ^ Hoyland 1999,第159頁.

- ^ Elad 1999,第23頁.

- ^ Elad 1999,第33頁.

- ^ Elad 1999,第23–24, 33頁.

- ^ 136.0 136.1 Hinds 1993,第266–267頁.

- ^ 137.0 137.1 137.2 137.3 137.4 137.5 Kennedy 2004,第83頁.

- ^ Kennedy 2004,第83–84頁.

- ^ Kennedy 2004,第84頁.

- ^ Kennedy 2004,第84–85頁.

- ^ 141.0 141.1 141.2 Kennedy 2004,第85頁.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927,第120頁.

- ^ 143.0 143.1 Wellhausen 1927,第121頁.

- ^ 144.0 144.1 Hasson 2002,第520頁.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927,第124頁.

- ^ Hawting 2000,第41頁.

- ^ 147.0 147.1 147.2 Foss 2009,第268頁.

- ^ Foss 2009,第269頁.

- ^ Foss 2009,第272頁.

- ^ Foss 2009,第269–270頁.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927,第135頁.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927,第135–136頁.

- ^ Bosworth 1991,第621–622頁.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927,第136頁.

- ^ Madelung 1997,第345, note 90頁.

- ^ Madelung 1997,第346頁.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927,第136–137頁.

- ^ 158.0 158.1 Miles 1948,第236頁.

- ^ Dixon 1971,第170頁.

- ^ Miles 1948,第238頁.

- ^ Miles 1948,第237頁.

- ^ Al-Rashid 2008,第270頁.

- ^ Al-Rashid 2008,第271, 273頁.

- ^ Kaegi 1995,第247頁.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927,第115頁.

- ^ 166.0 166.1 166.2 Jankowiak 2013,第273頁.

- ^ Kaegi 1995,第244–245, 247頁.

- ^ Kaegi 1995,第245, 247頁.

- ^ Jankowiak 2013,第273–274頁.

- ^ 170.0 170.1 Jankowiak 2013,第303–304頁.

- ^ Howard-Johnston 2010,第303–304頁.

- ^ Jankowiak 2013,第290頁.

- ^ Jankowiak 2013,第267, 274頁.

- ^ Jankowiak 2013,第304, 316頁.

- ^ Bosworth 1996,第159–160頁.

- ^ 176.0 176.1 Jankowiak 2013,第316頁.

- ^ Jankowiak 2013,第318頁.

- ^ Jankowiak 2013,第278–279, 316頁.

- ^ Stratos 1978,第46頁.

- ^ Lilie 1976,第81–82頁.

- ^ 181.0 181.1 Kennedy 2004,第88頁.

- ^ Kaegi 1995,第247–248頁.

- ^ Kennedy 2007,第207–208頁.

- ^ Kaegi 2010,第12頁.

- ^ 185.0 185.1 185.2 Christides 2000,第789頁.

- ^ 186.0 186.1 Kaegi 2010,第13頁.

- ^ 187.0 187.1 Kennedy 2007,第209頁.

- ^ 188.0 188.1 188.2 Christides 2000,第790頁.

- ^ Kennedy 2007,第217頁.

- ^ Lewis 2002,第67頁.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927,第146頁.

- ^ Hinds 1991,第139–140頁.

- ^ Madelung 1997,第339–340頁.

- ^ 194.0 194.1 Madelung 1997,第340–342頁.

- ^ 195.0 195.1 Hinds 1991,第139頁.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927,第137頁.

- ^ 197.0 197.1 de Goeje 1911,第28頁.

- ^ Gibb 1960,第85頁.

- ^ Marsham 2013,第90頁.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927,第141, 143頁.

- ^ Morony 1987,第183頁.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927,第142頁.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927,第143–144頁.

- ^ Hawting 2002,第309頁.

- ^ Marsham 2013,第90–91頁.

- ^ Marsham 2013,第91頁.

- ^ Crone 1994,第45頁.

- ^ Madelung 1997,第342–343頁.

- ^ Donner 2012,第177頁.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927,第145–146頁.

- ^ Hawting 2000,第43頁.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927,第144–145頁.

- ^ Morony 1987,第210, 212–213頁.

- ^ Morony 1987,第210頁.

- ^ Morony 1987,第209, 213–214頁.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927,第139頁.

- ^ Morony 1987,第213頁.

- ^ Morony 1987,第213–214頁.

- ^ Grabar 1966,第18頁.

- ^ Crone & Hinds 2003,第6–7頁.

- ^ Crone & Hinds 2003,第6頁.

- ^ Humphreys 2006,第93頁.

- ^ 223.0 223.1 Wellhausen 1927,第137–138頁.

- ^ Crone 2003,第30頁.

- ^ 225.0 225.1 Crone 2003,第33頁.

- ^ Hawting 2002,第310頁.

- ^ Kennedy 2004,第98頁.

- ^ 228.0 228.1 Kennedy 2016,第34頁.

- ^ Kennedy 2004,第82頁.

- ^ Humphreys 2006,第112–113頁.

- ^ 231.0 231.1 Madelung 1997,第326–327頁.

- ^ Hoyland 2015,第98頁.

- ^ Hoyland 2015,第266 n. 30頁.

- ^ Hoyland 2015,第135–136, 266 n. 30頁.

- ^ 235.0 235.1 Hoyland 2015,第233頁.

- ^ Hawting 2000,第16–17頁.

- ^ Humphreys 2006,第3–6頁.

- ^ 238.0 238.1 238.2 238.3 238.4 238.5 238.6 238.7 Hawting 2000,第42頁.

- ^ Humphreys 2006,第119頁.

- ^ 240.0 240.1 Humphreys 2006,第121頁.

- ^ 241.0 241.1 241.2 Hoyland 2015,第134頁.

- ^ 242.0 242.1 Crone & Hinds 2003,第115頁.

- ^ Morony 1986,第184–185頁.

- ^ Lewis 2002,第65頁.

- ^ Kennedy 2007,第349頁.

- ^ Humphreys 2006,第115頁.

- ^ Ende 1977,第14頁.

- ^ 248.0 248.1 248.2 Kohlberg 2020,第105頁.

- ^ Kohlberg 2020,第105, note 136頁.

- ^ Kohlberg 2020,第105–106頁.

- ^ Pierce 2016,第83–85頁.

- ^ Kohlberg 2020,第103頁.

- ^ 253.0 253.1 Kohlberg 2020,第104頁.

- ^ Hyder 2006,第82頁.

- ^ Kraemer 1992,第64–65頁.

- ^ Halm 2003,第90, 192頁.

來源

[編輯]- Athamina, Khalil. The Appointment and Dismissal of Khalid ibn al-Walid from the Supreme Command: A Study of the Political Strategy of the Early Muslim Caliphs in Syria. Arabica (Brill). 1994, 41 (2): 253–272. JSTOR 4057449. doi:10.1163/157005894X00191.

- Bosworth, C. Edmund. Marwān I b. al-Ḥakam. Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Pellat, Ch. (編). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume VI: Mahk–Mid. Leiden: E. J. Brill: 621–623. 1991. ISBN 978-90-04-08112-3.

- Bosworth, C. Edmund. Arab Attacks on Rhodes in the Pre-Ottoman Period. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. 1996, 6 (2): 157–164. JSTOR 25183178. doi:10.1017/S1356186300007161.

- Christides, Vassilios. ʿUkba b. Nāfiʿ. Bearman, P. J.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. (編). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume X: T–U. Leiden: E. J. Brill: 789–790. 2000. ISBN 978-90-04-11211-7.

- Crone, Patricia; Hinds, Martin. God's Caliph: Religious Authority in the First Centuries of Islam. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2003 [1986]. ISBN 0-521-32185-9.

- Crone, Patricia. Were the Qays and Yemen of the Umayyad Period Political Parties?. Der Islam (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter & Co.). 1994, 71 (1): 1–57. ISSN 0021-1818. S2CID 154370527. doi:10.1515/islm.1994.71.1.1.

- Crone, Patricia. Slaves on Horses: The Evolution of the Islamic Polity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1980. ISBN 0-521-52940-9.

- Dixon, 'Abd al-Ameer A. The Umayyad Caliphate, 65–86/684–705: (a Political Study). London: Luzac. 1971. ISBN 978-0-7189-0149-3.

- Dixon, 'Abd al-Ameer A. Kalb b. Wabara – Islamic Period. van Donzel, E.; Lewis, B.; Pellat, Ch.; Bosworth, C. E. (編). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume IV: Iran–Kha. Leiden: E. J. Brill: 493–494. 1978. OCLC 758278456.

- Donner, Fred M. Muhammad and the Believers, at the Origins of Islam. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. 2012 [2010]. ISBN 978-0-674-05097-6.

- Donner, Fred M. The Early Islamic Conquests. Princeton: Princeton University Press. 2014 [1981]. ISBN 978-0-691-05327-1.

- Elad, Amikam. Medieval Jerusalem and Islamic Worship: Holy Places, Ceremonies, Pilgrimage 2nd. Leiden: Brill. 1999. ISBN 90-04-10010-5.

- Ende, Werner. Arabische Nation und islamische Geschichte: Die Umayyaden im Urteil arabischer Autoren des 20. Jahrhunderts. Beirut: Orient-Institut der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft. 1977 [1974].

- Gardet, Louis. Fitna. Lewis, B.; Pellat, Ch.; Schacht, J. (編). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume II: C–G. Leiden: E. J. Brill: 930–931. 1965. OCLC 495469475.

- de Goeje, Michael Jan. Caliphate. Chisholm, Hugh (編). Encyclopædia Britannica 5 (第11版). London: Cambridge University Press: 23–54. 1911.

- Grabar, Oleg. The Earliest Islamic Commemorative Structures, Notes and Documents. Ars Orientalis. 1966, 6: 7–46. JSTOR 4629220.

- Fowden, Garth. Quṣayr ʻAmra: Art and the Umayyad Elite in Late Antique Syria. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. 2004. ISBN 0-520-23665-3.

- Foss, Clive. Muʿāwiya's State. Haldon, John (編). Money, Power and Politics in Early Islamic Syria: A Review of Current Debates. London and New York: Routledge. 2016 [2010]. ISBN 978-0-7546-6849-7.

- Foss, Clive. Egypt under Muʿāwiya Part II: Middle Egypt, Fusṭāṭ and Alexandria. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 2009, 72 (2): 259–278. JSTOR 40379004. doi:10.1017/S0041977X09000512

.

. - Gibb, H. A. R. ʿAbd al-Raḥmān b. Khālid b. al-Walīd. Gibb, H. A. R.; Kramers, J. H.; Lévi-Provençal, E.; Schacht, J.; Lewis, B.; Pellat, Ch. (編). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume I: A–B. Leiden: E. J. Brill: 85. 1960. OCLC 495469456.

- Halm, Heinz. Die Kalifen von Kairo: Die Fatimiden in Ägypten, 973–1074 [The Caliphs of Cairo: The Fatimids in Egypt, 973–1074]. Munich: C. H. Beck. 2003. ISBN 3-406-48654-1 (德語).

- Hasson, Isaac. Remarques sur l'inscription de l'époque de Mu'āwiya à Ḥammat Gader [Notes on the inscription from the time of Mu'āwiya to Ḥammat Gader]. Israel Exploration Journal. 1982, 32 (2/3): 97–102. JSTOR 27925830 (法語).

- Hasson, Isaac. Ziyād b. Abīhi. Bearman, P. J.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. (編). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume XI: W–Z. Leiden: E. J. Brill: 519–522. 2002. ISBN 978-90-04-12756-2.

- Hawting, G.R. (編). The History of al-Ṭabarī, Volume XVII: The First Civil War: From the Battle of Siffīn to the Death of ʿAlī, A.D. 656–661/A.H. 36–40. SUNY Series in Near Eastern Studies. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. 1996. ISBN 978-0-7914-2393-6.

- Hawting, Gerald R. The First Dynasty of Islam: The Umayyad Caliphate AD 661–750 Second. London and New York: Routledge. 2000. ISBN 0-415-24072-7 (英語).

- Hawting, Gerald R. Yazīd (I) b. Muʿāwiya. Bearman, P. J.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. (編). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume XI: W–Z. Leiden: E. J. Brill: 309–311. 2002. ISBN 978-90-04-12756-2.

- Hinds, Martin. The Siffin Arbitration Agreement. Journal of Semitic Studies. 1972, 17 (1): 93–129. doi:10.1093/jss/17.1.93.

- Hinds, Martin. Makhzūm. Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Pellat, Ch. (編). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume VI: Mahk–Mid. Leiden: E. J. Brill: 137–140. 1991. ISBN 978-90-04-08112-3.

- Hinds, Martin. Muʿāwiya I b. Abī Sufyān. Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P.; Pellat, Ch. (編). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume VII: Mif–Naz. Leiden: E. J. Brill: 263–268. 1993. ISBN 978-90-04-09419-2.

- Hirschfeld, Yizhar. The History and Town-Plan of Ancient Ḥammat Gādẹ̄r. Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 1987, 103: 101–116. JSTOR 27931308.

- Howard-Johnston, James. Witnesses to a World Crisis: Historians and Histories of the Middle East in the Seventh Century. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2010. ISBN 978-0-19-920859-3.

- Hoyland, Robert G. Jacob of Edessa on Islam. Reinink, G. J.; Klugkist, A. C. (編). After Bardaisan: Studies on Continuity and Change in Syriac Christianity in Honour of Professor Han J. W. Drijvers. Leuven: Peeters Publishers. 1999. ISBN 90-429-0735-5.

- Hoyland, Robert G. In God's Path: the Arab Conquests and the Creation of an Islamic Empire. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2015. ISBN 978-0-19-991636-8.

- Humphreys, R. Stephen. Mu'awiya ibn Abi Sufyan: From Arabia to Empire. Oneworld. 2006. ISBN 1-85168-402-6.

- Hyder, Syed Akbar. Reliving Karbala: Martyrdom in South Asian Memory. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2006. ISBN 978-0-19-537302-8.

- Jandora, John W. Developments in Islamic Warfare: The Early Conquests. Studia Islamica. 1986, (64): 101–113. JSTOR 1596048. doi:10.2307/1596048.

- Jankowiak, Marek. The First Arab Siege of Constantinople. Zuckerman, Constantin (編). Travaux et mémoires, Vol. 17: Constructing the Seventh Century. Paris: Association des Amis du Centre d』Histoire et Civilisation de Byzance. 2013: 237–320.

- Kaegi, Walter E. Byzantium and the Early Islamic Conquests. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1995 [1992]. ISBN 0-521-41172-6.

- Kaegi, Walter E. Muslim Expansion and Byzantine Collapse in North Africa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2010. ISBN 978-0-521-19677-2.

- Kennedy, Hugh. Egypt as a Province in the Islamic Caliphate, 641–868. Petry, Carl F. (編). The Cambridge History of Egypt, Volume 1: Islamic Egypt, 640–1517. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1998: 62–85. ISBN 0-521-47137-0 (英語).

- Kennedy, Hugh. The Armies of the Caliphs: Military and Society in the Early Islamic State. London and New York: Routledge. 2001. ISBN 0-415-25093-5.

- Kennedy, Hugh. The Prophet and the Age of the Caliphates: The Islamic Near East from the 6th to the 11th Century Second. Harlow: Longman. 2004. ISBN 978-0-582-40525-7.

- Kennedy, Hugh. The Great Arab Conquests: How the Spread of Islam Changed the World We Live In. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Da Capo Press. 2007. ISBN 978-0-306-81740-3.

- Kennedy, Hugh. Caliphate: The History of an Idea. New York: Basic Books. 2016. ISBN 978-0-465-09439-4.

- Kohlberg, Etan. In Praise of the Few. Studies in Shiʿi Thought and History. Leiden: Brill. 2020. ISBN 978-90-04-40697-1.

- Kraemer, Joel L. Humanism in the Renaissance of Islam: The Cultural Revival During the Buyid Age Second Revised. Leiden, New York and Koln: Brill. 1992 [1986]. ISBN 90-04-09736-8.

- Lammens, Henri. Baḥdal. Gibb, H. A. R.; Kramers, J. H.; Lévi-Provençal, E.; Schacht, J.; Lewis, B.; Pellat, Ch. (編). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume I: A–B. Leiden: E. J. Brill: 919–920. 1960. OCLC 495469456.

- Lewis, Bernard. Arabs in History. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2002. ISBN 978-0-19-164716-1.

- Lilie, Ralph-Johannes. Die byzantinische Reaktion auf die Ausbreitung der Araber. Studien zur Strukturwandlung des byzantinischen Staates im 7. und 8. Jhd. [The Byzantine Response to the Spread of the Arabs. Studies on the structural change of the Byzantine state in the 7th and 8th centuries]. Munich: Institut für Byzantinistik und Neugriechische Philologie der Universität München. 1976. OCLC 797598069 (德語).

- Lynch, Ryan J. Cyprus and Its Legal and Historiographical Significance in Early Islamic History. Journal of the American Oriental Society. 2016, 136 (3): 535–550. JSTOR 10.7817/jameroriesoci.136.3.0535. doi:10.7817/jameroriesoci.136.3.0535.

- Madelung, Wilferd. The Succession to Muhammad: A Study of the Early Caliphate. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1997. ISBN 0-521-56181-7.

- Marsham, Andrew. The Architecture of Allegiance in Early Islamic Late Antiquity: The Accession of Mu'awiya in Jerusalem, ca. 661 CE. Beihammer, Alexander; Constantinou, Stavroula; Parani, Maria (編). Court Ceremonies and Rituals of Power in Byzantium and the Medieval Mediterranean. Leiden and Boston: Brill. 2013: 87–114. ISBN 978-90-04-25686-6.

- Miles, George C. Early Islamic Inscriptions Near Ṭāʾif in the Ḥijāz. Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 1948, 7 (4): 236–242. JSTOR 542216. S2CID 162403885. doi:10.1086/370887.

- Morony, M. Kisrā. Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Lewis, B.; Pellat, Ch. (編). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume V: Khe–Mahi. Leiden: E. J. Brill: 184–185. 1986. ISBN 978-90-04-07819-2.

- Pierce, Matthew. Twelve Infallible Men: The Imams and the Making of Shiʿism. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. 2016. ISBN 978-0-674-73707-5.

- Al-Rashid, Saad bin Abdulaziz. Sadd al-Khanaq: An Early Umayyad Dam near Medina, Saudi Arabia. Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies (Archaeopress). 2008, 38: 265–275. JSTOR 41223953.

- Morony, Michael G. (編). The History of al-Ṭabarī, Volume XVIII: Between Civil Wars: The Caliphate of Muʿāwiyah, 661–680 A.D./A.H. 40–60. SUNY Series in Near Eastern Studies. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. 1987. ISBN 978-0-87395-933-9.

- Shaban, M. A. Islamic History, A New Interpretation: Volume 1, AD 600–750 (A.H. 132). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1976 [1971]. ISBN 978-0-521-29131-6.

- Shahid, Irfan. Tanūkh. Bearman, P. J.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. (編). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume X: T–U. Leiden: E. J. Brill: 190–192. 2000. ISBN 978-90-04-11211-7.

- Shahid, Irfan. Ṭayyīʾ. Bearman, P. J.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. (編). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume X: T–U. Leiden: E. J. Brill: 402–403. 2000. ISBN 978-90-04-11211-7.

- Sharon, Moshe. Witnessed by Three Disciples of the Prophet: The Jerusalem 32 Inscription from 32 AH/652 CE. Israel Exploration Journal. 2018, 68 (1): 100–111. JSTOR 26740639.

- Sourdel, D. Filasṭīn – I. Palestine under Islamic Rule. Lewis, B.; Pellat, Ch.; Schacht, J. (編). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume II: C–G. Leiden: E. J. Brill: 910–913. 1965. OCLC 495469475.

- Sprengling, Martin. From Persian to Arabic. The American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures (The University of Chicago Press). 1939, 56 (2): 175–224. JSTOR 528934. S2CID 170486943. doi:10.1086/370538.

- Stratos, Andreas N. Byzantium in the Seventh Century, Volume IV: 668–685. Amsterdam: Adolf M. Hakkert. 1978. ISBN 978-90-256-0665-7.

- Vaglieri, L. Veccia. ʿAlī b. Abī Ṭālib. Gibb, H. A. R.; Kramers, J. H.; Lévi-Provençal, E.; Schacht, J.; Lewis, B.; Pellat, Ch. (編). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume I: A–B. Leiden: E. J. Brill: 381–386. 1960. OCLC 495469456.

- Watt, W. Montgomery. Abū Sufyān. Gibb, H. A. R.; Kramers, J. H.; Lévi-Provençal, E.; Schacht, J.; Lewis, B.; Pellat, Ch. (編). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume I: A–B. Leiden: E. J. Brill: 151. 1960. OCLC 495469456.

- Watt, W. Montgomery. Badr. Gibb, H. A. R.; Kramers, J. H.; Lévi-Provençal, E.; Schacht, J.; Lewis, B.; Pellat, Ch. (編). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume I: A–B. Leiden: E. J. Brill: 866–867. 1960. OCLC 495469456.

- Wellhausen, Julius. The Arab Kingdom and its Fall. 由Margaret Graham Weir翻譯. Calcutta: University of Calcutta. 1927. OCLC 752790641.

延伸閱讀

[編輯]- Shahin, Aram A. In Defense of Mu’awiya ibn Abi Sufyan: Treatises and Monographs on Mu’awiya from the Eighth to Nineteenth Centuries. Cobb, Paul M. (編). The Lineaments of Islam: Studies in Honor of Fred McGraw Donner. Leiden and Boston: Brill. 2012: 177–208. ISBN 978-90-04-21885-7.

Dkzzl/阿季奈迪恩戰役 出生於:602逝世於:26 April 680

| ||

|---|---|---|

| 前任者: Hasan ibn Ali |

Caliph of Islam Umayyad Caliph 661–680 |

繼任者: Yazid I |