前王朝时期

史前埃及 前王朝时期 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| |||||||

历史系列条目 |

|---|

| 埃及历史 |

|

|

|

前王朝时期,又称史前埃及,是从埃及最早的人类定居点开始,到公元前3100年左右第一王朝成立的时期,也是埃及文明的第一时期。而在史前时代结束后,“前王朝时期”在传统上被定义为从新石器时代的最后部分(约公元前6200年)到涅伽达三期文化结束(约公元前3000年)的时期。约前40世纪,埃及人开始在各地建立城邦,当中包括底比斯、孟斐斯、布陀、希拉康波利斯、厄勒芬廷、阿拜多斯、提尼斯、赛伊斯、索伊斯、赫利奥波利斯、布巴斯提斯、坦尼斯,前王朝时代如是开始。直至前31世纪美尼斯统一上下埃及,前王朝时期结束,早王朝时期开始。

前王朝时期在时间上跨越的尺度在埃及大规模考古发掘就确定了,但后来关于埃及前王朝时期探索的进程十分缓慢,导致前王朝时期究竟何时结束的争议。因此大家用各种如“原王朝时期”、“第零王朝”[1]来命名此时期和埃及早期王朝。前王朝时期通常被划分为不同的文化,这些文化常常得名于首次发现该文化特征的埃及定居点。然而,原始王朝时期的渐进式发展贯穿整个前王朝时期,各个“文化”不应被分别看待。这种主观划分只是为了便于研究整个时期。考古学家发现的绝大多数关于前王朝时期的遗址来自上埃及,因为尼罗河的淤泥在下埃及三角洲地区沉积得更为严重,掩埋了下埃及大部分的前王朝遗址。[2]

旧石器时代

[编辑]尽管有关早期埃及人类居住的证据稀少且零散,包括早期人类在内,埃及有人类居住的时间已有超过一百万年(可能超过两百万年)。埃及最古老的考古发现是属于奥都万文化的石器,而这些石器的年代确定得不太准确。随后,这些工具阿舍利文化的石器取代。[3]埃及最早的阿舍利文化遗址可追溯到大约40至30万年前。[4]

瓦迪哈勒法

[编辑]一些已知最古老的建筑结构是在埃及阿尔金8号遗址由考古学家瓦尔德玛尔·赫米勒夫斯基(Waldemar Chmielewski)发现的,这个遗址位于苏丹的瓦迪哈勒法。赫米勒夫斯基将这些结构的年代确定为公元前100,000年。[5]这些结构的遗迹是深约30厘米,横跨2米 × 1米的椭圆形坑洞。许多坑洞内有平坦的砂岩板,作为帐篷环,支撑着由皮革或树枝制成的圆顶状庇护所。这种类型的住所提供了居住的场所,但必要时也便于拆卸和运输。这些可以轻松拆卸、移动和重新组装结构为狩猎采集者提供了半永久的居住地。[5]

阿特拉工具

[编辑]

阿特拉文化[6]的工具制作技术大约在距今40000年进入埃及。[5]

霍尔穆桑工具

[编辑]埃及的霍尔穆桑文化开始于公元前42000年到32000年之间。[5]霍尔穆桑人不仅用石头制作工具,还用动物骨头和赤铁矿。[5]他们还制作了类似美洲原住民的小箭头,但并未发现弓。[5]霍尔穆桑文化大约在公元前16000年,随着包括格迈安文化在内的其他文化的出现而结束。[7]

旧石器时代晚期

[编辑]埃及的旧石器时代晚期大约始于公元前30000年。[5]1980年发现的纳兹莱特·哈特尔骨骼,在1982年根据年代介于距今35100年和30,360年九个样本,测定其年代为33000年。[8]这具标本是非洲石器时代晚期最早的一段时间中唯一保存完整的现代人类骨骼。[9]

上埃及的法胡里亚旧石器时代晚期文化表明,在晚更新世,尼罗河谷存在一个相似的人群。对骨骼材料的研究显示,其变化范围与瓦迪哈勒法、杰贝勒萨哈巴和考姆翁布人群的骨骼碎片相似。

中石器时代

[编辑]哈尔凡和库班尼亚文化

[编辑]哈尔凡和库班尼亚这两个密切相关的文化兴盛于上尼罗河谷。哈尔凡文化位于苏丹最北部,而库班尼亚文化则位于上埃及。对于哈尔凡文化,只有四个放射性碳定年数据。席尔德(Schild)和温多夫(Wendorf)于2014年排除了最早和最晚的日期,认为哈尔凡文化存在于距今约22.5-22.0千年前。[10]人们依靠大型牲畜和霍尔穆桑传统的捕鱼方式生存。更多的文物集中表明他们并非季节性游牧,而是长时间定居。哈法文化继承自霍尔穆桑文化,[注 1][12][页码请求]而后者依靠专业的狩猎、捕鱼和采集技术生存。这一文化的主要物质遗存是石器工具、石片和大量的岩画。

塞比利亚文化

[编辑]塞比利亚文化开始于约公元前13000年,并消失于约公元前10000年。考古遗址中发现的花粉分析表明,塞比利亚文化(也称为埃斯那文化)的人收集谷物,不过没有发现用于种植的种子。[13]根据假设,谷物收集者的定居生活方式导致了战争的增加,对定居生活不利,并导致了这一文化的终结。[13]

卡丹文化

[编辑]卡丹文化,自公元前13000年至9000年,是中石器时代文化,考古证据表明,卡丹文化大约在15000年前起源于上埃及。[14][15]卡丹文化的生存方式持续了大约4000年,其特征包括狩猎以及一种独特的食物采集方式,如收集并食用野草和谷物。[14][15]卡丹文化系统性地浇灌、照料并收获当地的植物,但谷物并未按有序的行列种植。[16]

上努比亚的约二十个考古遗址提供了卡丹文化为磨粮文化的证据。在萨哈巴达鲁尼罗河阶段初期,撒哈拉沙漠的干旱导致利比亚绿洲的居民迁往到尼罗河谷时,卡丹文化的人群还沿着尼罗河进行野生谷物的采集。[13]卡丹文化其中一个遗址是杰贝勒萨哈巴墓地,其年代被确定为中石器时代。[17]

卡丹文化最早创造了镰刀,还独立创造了磨石,以帮助收集和处理植物性食物,并在食用之前进行加工。[18]然而,在公元前10000年狩猎采集者取代了他们之后,便没有了使用这些工具的迹象。[18]

新石器时代至原始王朝时期

[编辑]尼罗河谷新石器时代文化的早期证据通常位于埃及北部,展示了新石器时代的生存方式,包括作物栽培和定居生活,以及公元前6千纪晚期开始的陶器生产。[19]

1947年,自然科学家弗雷德里克·法尔肯伯格(Frederick Falkenburger)基于大约1800个史前埃及颅骨样本,注意到样本间存在很大的差异。法尔肯伯格根据鼻指数、整体头部和面部形态(包括宽度、眼窝结构等指标)将这些颅骨分类为四种类型:克罗马侬类型、尼格罗类型、地中海类型和上述群体的混合类型。[20]同样根据医生兼人类学家尤金·斯特罗哈尔(Eugene Strouhal)1971年的研究,早期埃及人的颅骨测量数据被指定为北非的克罗马农类型、地中海类型、东非的尼格罗类型以及中间/混合类型。[21]

根据费克里·A·哈桑教授的研究,考古和生物数据表明,埃及尼罗河谷的人口组成是沿海北非人、新石器时代撒哈拉人、尼罗特狩猎者和生活在尼罗河沿岸地区的原始努比亚人之间复杂互动的结果,并受到来自黎凡特的影响和移民迁徙。[22]

下埃及

[编辑]法尤姆B文化(加龙文化)

[编辑]

法尤姆B文化,也被称为加龙文化,得名于加龙湖,是埃及上古石器时代(或中石器时代)的考古文化,位于法尤姆A文化之前。法尤姆B文化没有发现陶器,刀刃类型包括普通石器和细石器。一组勺子和箭簇表明法尤姆B文化可能与撒哈拉有所接触(约公元前6500年至公元前5190年)。[23][24]

马切伊·亨内伯格(Maciej Henneberg,1989)纪录了一个距今8000年的加龙文化老年女性头骨,它与瓦迪哈勒法、现代黑人和澳大利亚土著有密切联系,与北非(Mechta-Afalou,即古柏柏尔人)或者之后的原始地中海类型(卡普萨文化)的上古石器时代材料有明显不同。头骨具有折中的性质,一方面骨骼纤细,另一方面却拥有较大的牙齿和沉重的下颚骨。[25]2021年S. O. Y. 凯塔的简短报告中也得出了相似的结果,并说明了加龙文化与肯尼亚泰塔人的亲缘关系。[26]

法尤姆A文化

[编辑]在公元前5400年至公元前4400年的新石器时代法尤姆地区,[27][28],沙漠的不断扩大使得埃及人的祖先迁徙到尼罗河流域,并长久地定居下来。法尤姆A文化是尼罗河流域最早的农耕文化。[29]已发现的考古沉积物的特征是凹底的投射物与陶器。[30]公元前6200年左右,新石器时代的定居点出现在整个埃及范围内。一些基于生物形态学、[31]遗传学[32][33][34][35][36]和考古学数据[37][38][39][40][41]的研究将这些定居点归因于埃及和北非的新石器时代来自近东新月沃土的移民,他们将农业带来了这里。

人类学和后颅骨数据研究将法尤姆、梅里姆达和拜达里的最早农业人群与近东人群联系在一起。[42][43][44]考古证据还表明,近东的家养动物和植物被纳入了现有的觅食策略,但是在缓慢发展后才逐渐形成了一种完整的生活方式。[注 2][46][47]最终,引入埃及的近东家养动物的名称并不是苏美尔语或原始闪米特语的借词。[48][49]

然而,一些学者对这一观点提出了质疑,他们引用了语言学、[50]体质人类学、[51]考古学[52][53][54]和遗传学数据[55][56][57][58][59],这些数据不支持史前时期来自黎凡特的大规模迁移假说。历史学家威廉·斯蒂布林(William Stiebling)和考古学家苏珊·N·赫尔夫特(Susan N. Helft)认为,这一观点认为古埃及人与努比亚人及其他撒哈拉人是同一原始人口群体,而有一些来自阿拉伯、黎凡特、北非和印欧人的基因输入,这些人在埃及的漫长历史中定居于此。另一方面,斯蒂布林和赫尔夫特承认,北非人群的遗传研究通常表明在新石器时代或更早时期有大量近东人口的涌入。他们还补充说,目前关于古埃及DNA的研究很少,无法解释这些问题。[60]

埃及学家伊恩·肖在2003年写道:“人类学研究表明,前王朝时期的人口包括多种种族类型(尼格罗人种、地中海人种和欧洲人种)”,但在法老时期开始时的骨骼材料却是最具争议的。根据一些学者的观点,人群变化的过程可能比先前假设的来自东方的快速征服更为缓慢,可能涉及来自叙利亚-巴勒斯坦地区的不同类型逐步通过东部三角洲渗透。[61]

法尤姆A文化首次出现了纺织。另一方面,与后来的埃及人不同,这一时期的人们将死者埋在离他们的居住地非常近的地方,有时甚至直接埋在定居点内。[62]

尽管考古遗址关于这一时期的信息有限,但对许多埃及语中“城市”一词的研究,可以推测埃及人定居的原因。在上埃及,这一术语显示定居的原因包括贸易、保护牲畜、洪水避难的高地以及神祇的圣地等因素。[63]

梅里姆达文化

[编辑]梅里姆达文化[64],自约公元前5000年至公元前4200年在下埃及蓬勃发展,目前发现的只有尼罗河三角洲西部边缘的大型聚落遗址梅里姆达-贝尼-萨拉姆。梅里姆达文化与法尤姆A文化和黎凡特有密切联系。人们生活在小屋里,制作简单而没有装饰的陶器和石器。他们饲养牛、绵羊、山羊和猪,种植小麦、高粱和大麦。梅里姆达文化的人将逝者埋葬在定居点内,并制作泥塑。第一个真人大小的埃及泥塑头像就是来自梅里姆达文化。[65]

埃尔-奥马里文化

[编辑]埃尔-奥马里文化[64]得名于开罗附近的小定居点。人们可能居住在小屋里,但只有柱坑和坑洞留存。埃尔-奥马里文化的陶器没有装饰,石器包括小石片、斧头和镰刀,而金属尚不清楚。[66]埃尔-奥马里文化遗址自公元前4000年到埃及古风时期的公元前3100年都有人居住。[67]

马底文化

[编辑]

马底文化,也被称为布陀—马底文化,大约自公元前4000年至公元前3500年,是下埃及重要的史前文化,与涅伽代一期和二期文化同期。[68]马底文化得名于开罗附近的马底,这里也是布陀的所在地,并在从尼罗河三角洲到法尤姆地区的许多地方都有发现。马底文化的特点是建筑与技术的发展,而马底文化的无装饰陶瓷也延续了其先前的文化。[69]

马底文化已经有了铜,同时发现了一些铜锛,陶器以手工制作,但是简单而缺乏装饰。黑顶陶器的发现证明马底文化与其南方的涅伽达文化有联系。此外,还发现了许多从巴勒斯坦进口的容器,以及用黑色玄武岩制作的容器。[70]

马底文化的人群生活在部分挖入地下的小屋里。死者通常埋葬在墓地中,不过只有很少的随葬品。马底文化被涅伽达三期文化所取代,是通过征服还是渗透仍存在争议。[71]

多年来,下埃及在统一以前的发展存在很大的争议。近期在泰尔法卡、塞易斯和泰尔伊斯威德的发掘证实了这一点。总之,铜石并用时代的下埃及文化仍需要更多的研究。[72]

上埃及

[编辑]塔西文化

[编辑]塔西文化,自约公元前4500年出现在上埃及。塔西文化得名于尼罗河东岸艾斯尤特和艾赫米姆之间的塔西发现的墓葬。塔西文化组最早创造了一种红色和棕色,同时顶部和内部涂成黑色的黑顶陶器[62] 。黑顶陶器对追溯前王朝时期的埃及非常重要。前王朝时期的日期较为模糊,因此弗林德斯·皮特里爵士发明了年代序列法,从而判断相对日期。如果没有绝对日期,任何前王朝遗址的相对日期都可以通过研究发掘的陶器来确定。

随着前王朝时期的发展,陶器手柄的作用逐渐从实用功能转变为装饰功能。一个考古遗址中陶器作用的实用或装饰程度可以用于确定遗址的相对日期。塔西文化陶器与拜达里文化陶器只有很小的差别,因而塔西文化和拜达里文化在范围上有很大的重叠。[73] 从塔西文化开始,上埃及受到了下埃及文化的强烈影响。[74] 考古证据表明“塔西和拜达里文化时期尼罗河流域的定居点是早期非洲文化的外围网络,拜达里人、撒哈拉人、努比亚人和尼罗特人经常传播非洲文化”[75] 埃及学家布鲁斯•威廉姆斯(Bruce Williams)认为,塔西文化与新石器时代的苏丹-撒哈拉传统有很大关系,新石器时代的苏丹-撒哈拉传统从喀土穆以北延伸到苏丹东古拉附近的地区。[76]

拜达里文化

[编辑]

拜达里文化自公元前4400年至公元前4000年,[77]得名于塔西附近的拜达里。拜达里文化的时间在塔西文化之后,但因为两者非常相似,许多人认为它们是一个连续的时期。巴拜达里文化继续生产黑顶陶器,且质量有了很大提高,其年代序列编号为21到29。[73] 学者们没有将这两个时期合并的主要原因是,拜达里文化除了使用石器外还使用铜器,因此被认为是铜石并用时代的定居点,而塔西文化仍然被视为石器时代。[73]

拜达里文化的燧石工具继续发展,变得更为锋利而优美,并且出现了最早的陶釉制品。[78] 明确的拜达里遗址从尼肯一直延伸到阿拜多斯以北。[79]似乎法尤姆A文化与拜达里和塔西文化有明显的重叠,然而,法尤姆A文化较少从事农业,仍然属于新石器时代。[78][80] 许多生物人类学研究显示,拜达里人与其他东北非洲人口有很强的生物亲缘关系。[81][82][83][84][85][86] 然而,据尤金·斯特罗哈尔(Eugene Strouhal)和其他人类学家所述,拜达里文化的埃及人更类似于北非的卡普萨文化和柏柏尔人。[87]

2005年,凯塔(Keita)对上埃及前王朝时期的拜达里头骨与欧洲和热带非洲的各种头骨进行比较,他发现拜达里头骨与热带非洲更为接近。不过,研究中没有包括亚洲或其他北非的样本,因为这项比较是基于“布雷斯(Brace)等人(1993年)关于上埃及/努比亚在旧石器时代晚期相似性的评论”选出的。凯塔进一步指出,来自苏丹、晚期古埃及北方(吉萨)、索马里、亚洲和太平洋岛屿的额外分析和材料表明,“拜达里与非洲东北部最为相似,之后才是其他非洲人”。[88]

对拜达里化石进行的牙齿特征分析发现,他们与居住在东北非洲以及马格里布的阿非罗-亚细亚语系人群有着密切关系。在古代人群中,拜达里人与其他古埃及人(上埃及的涅伽达、希拉孔波利斯、阿拜多斯和哈里杰绿洲;下埃及的哈瓦拉),以及在下努比亚发掘的C组文化和法老时代的遗骸最为接近,其次是下努比亚的A组文化、上努比亚的克尔玛和库施,以及下努比亚的麦罗埃、X组和基督教时期的居民,还有达赫拉绿洲的凯利斯人群。[89]:219–20在现代人群中,拜达里在形态上与阿尔及利亚的肖威亚和卡拜勒柏柏尔人群以及摩洛哥、利比亚和突尼斯的贝都因人群最为接近,其次是非洲之角的其他阿非罗-亚细亚语系人群。[89]:222–224 凯利斯出土的拜达里晚罗马时期的骨骼在表型上也与撒哈拉以南非洲的其他人群明显不同。[89]:231–32

奈加代文化

[编辑]

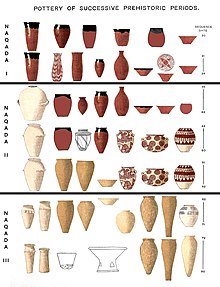

涅伽达文化也是铜石并用时代史前埃及的考古文化,时间自公元前4000年至公元前3000年,得名于埃及基纳省的涅伽达。涅伽达文化分为三个子时期:涅伽达一期文化(阿姆拉特文化)、涅伽达二期文化(格尔津文化)和涅伽达三期文化(原始王朝时期)。

与先前的拜达里文化类似,研究发现涅伽达文化的骨骼遗骸具有东北非洲的特征。[90][91][92][93][94][95]肖尔马卡·凯塔(Shormaka Keita)的研究发现,涅伽达的遗骸符合两种本地类型:南埃及的模式(与克尔马最为相似)和北埃及的模式(与沿海马格里布最为相似)。[96]

1996年,洛维尔(Lovell)和普罗斯(Prowse)报告了在涅伽达发现的被埋葬者,这些人被认为埋在高规格的贵族墓葬中,显示他们是涅伽达本地人口中内婚制的统治阶层或贵族,他们与努比亚北部(A组)的人群更为接近,而非与南埃及的邻近人群。具体而言,他们指出,涅伽达的样本“与下努比亚原始王朝时期样本的相似度高于与地理上更接近的南埃及的基纳和拜达里的样本”。然而,他们发现涅伽达墓地的骨骼样本与下努比亚的原始王朝时期人群,以及拜达里和基纳的埃及原始王朝时期样本都有明显不同(这二者之间也有显著不同)。[97]总体而言,涅伽达墓地中的贵族和非贵族个体彼此间更为相似,而与北努比亚的样本或南埃及的拜达里和基纳的样本相较之下差异较大。[98]

2023年,克里斯托弗·埃雷特(Christopher Ehret)报告称,“在公元前四千年古埃及起源地主要墓葬遗址(特别是拜达里和涅伽达)中的体质人类学研究发现,其人群没有受到黎凡特人群的显著影响。”埃雷特指出,研究揭示了这些头骨和牙齿特征与东北非洲周边地区长期定居人口(如努比亚和非洲之角北部)有着最为密切的相似性。他进一步评论道,这些人口的成员并非来自其他地方,而是这些地区数千年以来长期居民的后代。埃雷特还引用现有的考古、语言和遗传数据支持这段人群历史。[99]

阿姆拉特文化(奈加代一期文化)

[编辑]

阿姆拉特文化,自公元前4000年至公元前3500年,[100] 得名于拜达里以南120公里的阿姆拉。阿姆拉是第一个发现这一文化的遗址,并且并没有与格尔津文化混淆,但这一时期的文化在涅伽达得到了更好的诠释,因此阿姆拉特文化也被称为涅伽达一期文化。[101]黑顶陶器依然在这一时期出现,同时还发现了一种名为白色横纹陶器,这种陶器上装饰有一组紧密平行的白色线条,与另一组白色线条交叉。根据彼特里的年代序列法,阿姆拉特时期介于30期至39期之间。[102]

新发掘的物品证明了这一时期上埃及和下埃及之间的贸易有所增加。在阿姆拉发现了一只来自北方的石制花瓶。另外还有铜,而埃及不产铜,铜可能是从西奈或者努比亚进口的,黑曜石[103]和少量的黄金[102]都明确来自努比亚。与绿洲之间的贸易也很可能存在。[103]

阿姆拉定居点出现了新技术的创新,为后期文化奠定了基础。例如,格尔津文化以泥砖建筑著称,这些建筑最早出现在阿姆拉特文化,虽然数量很少。[104] 此外,椭圆和动物形状的调色板也出现在这一时期,但工艺非常粗糙,后来闻名的浮雕艺术尚未出现。[105][106]

格尔津文化(奈加代二期文化)

[编辑]

格尔津文化,自公元前3500年至公元前3200年,[107] 得名于遗址的发现地格尔津。它是埃及文化发展的下一阶段,并奠定了埃及王朝的基础。格尔津文化在很大程度上是从阿姆拉特文化发展而来的,影响范围自尼罗河三角洲向南经过上埃及,但未能在努比亚取代阿姆拉特文化。[108]格尔津文化的陶器按年代序列法位列40至62,与阿姆拉特的白色横纹陶器或黑顶陶器明显不同。[109] 格尔泽陶器多为暗红色,上面绘有动物、人物和船只的图案和可能来源于动物的几何符号。[108]此外,“波浪形 ”把手在这一时期之前非常罕见(虽然早在按年代序列法分期的第35期就偶尔发现),但在格尔津文化时期,“波浪形 ”把手越来越常见,也越来越精致,几乎完全成为装饰品。[109]

格尔津文化的兴起恰逢降雨量大幅减少,[110]因而此时尼罗河沿岸的农业生产了绝大多数食物,[108] 尽管绘画作品表明当时并没有完全放弃狩猎。随着粮食供应的增加,埃及人采用了更加定居的生活方式,城市也发展到 5000 座之多。[108]在这一时期,古埃及的城市居民停止使用芦苇建造建筑,开始大量生产泥砖(最早发现于阿姆拉特时期)来建造城市。[108]

古埃及人虽然仍在使用石器,但样式已从双面结构转变为波纹片状结构。铜被用于制作各种工具,[108]并出现了最早的铜制武器。[111]金、银、青金石以及埃及彩陶被用于装饰,[108] 而自拜达里文化时期起就用于眼部彩绘的陶制调色板上开始有了浮雕装饰。[111]

第一批古典埃及风格的陵墓也已建成,这些陵墓仿照普通房屋建造,有时由多个房间组成。[112] 人们普遍认为这种陵墓风格起源于尼罗河三角洲地区(尽管还需要进一步发掘),而不是上埃及。[112]

尽管格尔津文化已被明确认定为阿姆拉特文化的延续,但在格尔津文化时期,美索不达米亚文化对埃及产生了重要影响。这种影响过去被王朝种族学说解释为美索不达米亚统治阶级掌管上埃及的证据,而这一观点已不再对学术界有强烈的吸引力。

在这一时期,有明显的外来物品和艺术形式进入埃及,表明埃及与亚洲多个地区有接触。在埃及发现了格贝尔阿拉克刀的刀柄,上面有明显的美索不达米亚浮雕图案,[115] 而这一时期出现的银器只能从小亚细亚获得。[108]

此外还出现了明显模仿美索不达米亚形式但又并非一味模仿的埃及物品。[116] 埃及出现了圆筒形印章以及嵌入式镶板建筑,化妆台上的浮雕显然与当时美索不达米亚乌鲁克文化的风格相同,晚期格尔泽文化和早期“塞米诺文化”(即涅伽达三期文化)出土的礼仪用权杖头是按照美索不达米亚的 “梨形 ”风格制作的,而不是埃及本土风格。[110]

这条贸易路线很难确定,但埃及与迦南的接触并不早于早期王朝时期,因此通常假定贸易是通过水路进行的。[117] 在王朝种族学说仍然流行的时候,有人推测是乌鲁克水手跨越了阿拉伯半岛,但埃及出现的比布鲁斯物品证明,更有可能是通过比布鲁斯的中间商经由地中海进行贸易。[117]

许多格尔津遗址都位于通往红海的干河,表明有一定数量的贸易是通过红海进行的,比布鲁斯与埃及贸易路线可能自地中海穿过西奈半岛,然后取道红海。[118] 另外,嵌入式镶板建筑等复杂的技术不太可能通过间接方式进入埃及,通常怀疑至少有一小批移民带来了这项技术。[117]

尽管有这些外来影响,埃及学家普遍认为,格尔津文化仍是埃及本土文化。

原始王朝时期(奈加代三期文化)

[编辑]

涅伽达三期文化,约公元前 3200 年至公元前 3000 年,[119]通常被认为与埃及统一之前的“原始王朝时期”(Protodynastic period)相同。 在涅伽达三期文化时期,首次出现了象形文字(目前存在争议),首次有规律地使用塞拉赫纹章,首次进行灌溉并且首次出现了王室墓地。[120]

生物考古学家南希·洛弗尔(Nancy Lovell)指出,有足够多的形态学证据表明,古埃及南方人的身体特征“在撒哈拉和热带非洲古今土著人的变化范围之内”,并总结道:“总的来说,上埃及和努比亚的居民与撒哈拉和更南部地区的居民在生物学上最相近”,[122]但在在非洲范围内又表现出差异。[123]

-

前王朝时期带有王室夫妇的权杖碎片,现藏于慕尼黑国家埃及艺术收藏馆(Staatliche Sammlung für Ägyptische Kunst)

-

描绘了一个人和一支手杖的礼仪调色板残片,约公元前3200 - 公元前3100年,前王朝时期涅伽达三期文化晚期

下努比亚

[编辑]纳巴塔沙漠盆地

[编辑]

纳巴塔沙漠盆地曾是努比亚沙漠中的一个大型内流盆地,位于现代开罗以南约800公里[124],以及阿布辛拜勒以西约100公里[125],具体位置是北纬22.51度,东经30.73度。如今该地区有许多考古遗址。纳巴塔沙漠盆地的考古遗址是埃及新石器时代最早的遗址之一,可以追溯到约公元前7500年。[126][127]发掘表明,该地区新石器时代的居民包括来自撒哈拉以南非洲和地中海地区的移民。[128][129]根据克里斯托弗·埃雷特的研究,物质文化指标显示,更大范围的纳巴塔沙漠区域居民是尼罗-撒哈拉语系人群。[130]

时间线

[编辑](所有日期均为近似日期)

- 旧石器时代晚期,始于公元前40000年

- 新石器时代,始于公元前 11 世纪

- 约公元前10500年:尼罗河沿岸收获了野生谷物,谷物磨制文化创造了世界上最早的石制镰刀,[18]时间大致在更新世末期

- 约公元前8000年:人们迁徙到尼罗河,发展出更加集中的社会和定居的农业经济

- 约公元前7500年:从亚洲向撒哈拉引入动物

- 约公元前7000年:东撒哈拉发展出包括畜牧业和谷物业在内的农业;在纳巴塔开凿了深层的常年水井,并设计有计划安排的大型有组织居住区

- 约公元前6000年:埃及岩画中出现了初级船只,如划船和单帆船

- 约公元前5500年:纳巴塔出现有石顶的地下墓室和其他地下建筑群,里面埋葬着祭牛

- 约公元前5000年:考古发现了纳巴塔的天文巨石;[131][132]拜达里文化中发现了家具、餐具、长方形的房屋模型、壶、碟、杯、碗、花瓶、雕像以及梳子

- 约公元前4400年: 精细编织的亚麻布碎片[133]

- 从公元前4000年开始,出现了各种先进的创造

相对年表

[编辑]相关条目

[编辑]注释

[编辑]参考资料

[编辑]- ^ Leprohon, Ronald, J. The great name : ancient Egyptian royal titulary. Society of Biblical Literature. 2013. ISBN 978-1-58983-735-5.

- ^ Redford, Donald B. Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times

. Princeton: University Press. 1992: 10. ISBN 9780691036069.

. Princeton: University Press. 1992: 10. ISBN 9780691036069.

- ^ Bakry, Aboualhassan; Saied, Ahmed; Ibrahim, Doaa. The Oldowan in the Egyptian Nile Valley. Journal of African Archaeology. 2020-07-21, 18 (2): 229–241. ISSN 1612-1651. doi:10.1163/21915784-20200010.

- ^ Michalec, Grzegorz; Cendrowska, Marzena; Andrieux, Eric; Armitage, Simon J.; Ehlert, Maciej; Kim, Ju Yong; Sohn, Young Kwan; Krupa-Kurzynowska, Joanna; Moska, Piotr; Szmit, Marcin; Masojć, Mirosław. A Window into the Early–Middle Stone Age Transition in Northeastern Africa—A Marine Isotope Stage 7a/6 Late Acheulean Horizon from the EDAR 135 Site, Eastern Sahara (Sudan). Journal of Field Archaeology. 2021-11-17, 46 (8): 513–533. ISSN 0093-4690. doi:10.1080/00934690.2021.1993618 (英语).

- ^ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 Ancient Egyptian Culture: Paleolithic Egypt. Emuseum. Minnesota: Minnesota State University. [13 April 2012]. (原始内容存档于1 June 2010).

- ^ 潘华琼. 非洲考古与人类的“摇篮”. 中国投资(中英文). 2020, (Z2): 96-97.

- ^ Nicolas-Christophe Grimal. A History of Ancient Egypt. p. 20. Blackwell (1994). ISBN 0-631-19396-0

- ^ Dental Anthropology (PDF). Anthropology.osu.edu. [2013-10-25]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于29 October 2013). 已忽略未知参数

|df=(帮助) - ^ Bouchneba, L.; Crevecoeur, I. The inner ear of Nazlet Khater 2 (Upper Paleolithic, Egypt). Journal of Human Evolution. 2009, 56 (3): 257–262. Bibcode:2009JHumE..56..257B. PMID 19144388. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2008.12.003.

- ^ R. Schild; F. Wendorf. Late Palaeolithic Hunter-Gatherers in the Nile Valley of Nubia and Upper Egypt. E A. A. Garcea (编). South-Eastern Mediterranean Peoples Between 130,000 and 10,000 years ago. Oxbow Books: 89–125. 2014.

- ^ Prehistory of Nubia. Numibia.net. [2013-10-25]. (原始内容存档于29 October 2013). 已忽略未知参数

|df=(帮助) - ^ Reynes, Midant-Beatrix. The Prehistory of Egypt: From the First Egyptians to the First Pharohs. Wiley-Blackwell. 2000. ISBN 0-631-21787-8.

- ^ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Grimal, Nicolas. A History of Ancient Egypt. Librairie Arthéme Fayard. 1988: 21.

- ^ 14.0 14.1 Phillipson, DW: African Archaeology p. 149. Cambridge University Press, 2005.

- ^ 15.0 15.1 Shaw, I & Jameson, R: A Dictionary of Archaeology, p. 136. Blackwell Publishers Ltd, 2002.

- ^ Darvill, T: The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Archaeology, Copyright © 2002, 2003 by Oxford University Press.

- ^ Kelly, Raymond. The evolution of lethal intergroup violence. PNAS. October 2005, 102 (43): 24–29. Bibcode:2005PNAS..10215294K. PMC 1266108

. PMID 16129826. doi:10.1073/pnas.0505955102

. PMID 16129826. doi:10.1073/pnas.0505955102  .

.

- ^ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 18.4 18.5 Ancient Egyptian Culture: Paleolithic Egypt. Emuseum. Minnesota: Minnesota State University. [13 April 2012]. (原始内容存档于1 June 2010).

- ^ Köhler, E. Christiana. Neolithic in the Nile Valley (Fayum A, Merimde, el-Omari, Badarian). Archéo-Nil. 2011, 21 (1): 17–20. doi:10.3406/arnil.2011.1023.

- ^ Boëtsch, Gilles. Noirs ou blancs : une histoire de l'anthropologie biologique de l'Égypte. Égypte/Monde arabe. 1995-12-31, (24): 113–138. ISSN 1110-5097. doi:10.4000/ema.643 (法语).

Falkenburger also notes a great heterogeneity in the measurements taken on 1,800 Egyptian skulls. From indices expressing the shape of the face, nose and orbits, Falkenburger divides the ancient Egyptians into four types - Cro-Magnon type, Negroid type, Mediterranean type and mixed type, resulting from the mixture of the first three.

- ^ Strouhal, Eugen. Evidence of the early penetration of Negroes into prehistoric Egypt. The Journal of African History. 1971-01-01, 12 (1): 1–9. ISSN 1469-5138. doi:10.1017/S0021853700000037 (英语).

- ^ Hassan, Fekri A. The Predynastic of Egypt. Journal of World Prehistory. 1988-06-01, 2 (2): 135–185. ISSN 1573-7802. doi:10.1007/BF00975416 (英语).

- ^ Fayum, Qarunian (Fayum B) (about 6000-5000 BC?). Digital Egypt for Universities. University College London. [September 23, 2024].

- ^ Ki-Zerbo[editor], Joseph. General history of Africa, abridged edition, v. 1: Methodology and African prehistory. UNESCO Digital Library. The University of California Press: 281. 1989 [September 23, 2024].

- ^ Hendrickx, Stan; Claes, Wouter; Tristant, Yann. IFAO - Bibliographie de l'Égypte des Origines : #2998 = The Early Neolithic, Qarunian burial from the Northern Fayum Desert (Egypt). www.ifao.egnet.net. [2024-09-24] (法语).

- ^ Keita, S.O.Y. Title: Short Report: Morphometric Affinity of the Qarunian Early Egyptian Skull Explored With Fordisc 3.0. Academia.edu. 2020-08-01.

- ^ Köhler, E. Christiana. Neolithic in the Nile Valley (Fayum A, Merimde, el-Omari, Badarian). Archéo-Nil. 2011, 21 (1): 17–20. doi:10.3406/arnil.2011.1023.

- ^ Fayum, Qarunian (Fayum B) (about 6000-5000 BC?). Digital Egypt for Universities. University College London. [September 23, 2024].

- ^ Köhler, E. Christiana. Neolithic in the Nile Valley (Fayum A, Merimde, el-Omari, Badarian). Archéo-Nil. 2011, 21 (1): 17–20. doi:10.3406/arnil.2011.1023.

- ^ Redford, Donald B. Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times

. Princeton: University Press. 1992: 6. ISBN 9780691036069.

. Princeton: University Press. 1992: 6. ISBN 9780691036069.

- ^ Brace, C. Loring; Seguchi, Noriko; Quintyn, Conrad B.; Fox, Sherry C.; Nelson, A. Russell; Manolis, Sotiris K.; Qifeng, Pan. The questionable contribution of the Neolithic and the Bronze Age to European craniofacial form. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006, 103 (1): 242–247. Bibcode:2006PNAS..103..242B. PMC 1325007

. PMID 16371462. doi:10.1073/pnas.0509801102

. PMID 16371462. doi:10.1073/pnas.0509801102  .

.

- ^ Chicki, L; Nichols, RA; Barbujani, G; Beaumont, MA. Y genetic data support the Neolithic demic diffusion model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002, 99 (17): 11008–11013. Bibcode:2002PNAS...9911008C. PMC 123201

. PMID 12167671. doi:10.1073/pnas.162158799

. PMID 12167671. doi:10.1073/pnas.162158799  .

.

- ^ Estimating the Impact of Prehistoric Admixture on the Genome of Europeans, Dupanloup et al., 2004. Mbe.oxfordjournals.org. [1 May 2012]. (原始内容存档于11 March 2007).

- ^ Semino, O; Magri, C; Benuzzi, G; et al. Origin, Diffusion, and Differentiation of Y-Chromosome Haplogroups E and J: Inferences on the Neolithization of Europe and Later Migratory Events in the Mediterranean Area, 2004. Am. J. Hum. Genet. May 2004, 74 (5): 1023–34. PMC 1181965

. PMID 15069642. doi:10.1086/386295.

. PMID 15069642. doi:10.1086/386295.

- ^ Cavalli-Sforza. Paleolithic and Neolithic lineages in the European mitochondrial gene pool. Am J Hum Genet. 1997, 61 (1): 247–54 [1 May 2012]. PMC 1715849

. PMID 9246011. doi:10.1016/S0002-9297(07)64303-1.

. PMID 9246011. doi:10.1016/S0002-9297(07)64303-1.

- ^ Chikhi. Clines of nuclear DNA markers suggest a largely Neolithic ancestry of the European gene. PNAS. 21 July 1998, 95 (15): 9053–9058. Bibcode:1998PNAS...95.9053C. PMC 21201

. PMID 9671803. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.15.9053

. PMID 9671803. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.15.9053  .

.

- ^ Bar Yosef, Ofer. The Natufian Culture in the Levant, Threshold to the Origins of Agriculture. Evolutionary Anthropology. 1998, 6 (5): 159–177. S2CID 35814375. doi:10.1002/(sici)1520-6505(1998)6:5<159::aid-evan4>3.0.co;2-7.

- ^ Zvelebil, M. Hunters in Transition: Mesolithic Societies and the Transition to Farming. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. 1986: 5–15, 167–188.

- ^ Bellwood, P. First Farmers: The Origins of Agricultural Societies. Malden, MA: Blackwell. 2005.

- ^ Dokládal, M.; Brožek, J. Physical Anthropology in Czechoslovakia: Recent Developments. Current Anthropology. 1961, 2 (5): 455–477. S2CID 161324951. doi:10.1086/200228.

- ^ Zvelebil, M. On the transition to farming in Europe, or what was spreading with the Neolithic: a reply to Ammerman (1989). Antiquity. 1989, 63 (239): 379–383. S2CID 162882505. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00076110.

- ^ Smith, P. (2002) The palaeo-biological evidence for admixture between populations in the southern Levant and Egypt in the fourth to third millennia BC. In: Egypt and the Levant: Interrelations from the 4th through the Early 3rd Millennium BC, London–New York: Leicester University Press, 118–128

- ^ Keita, S.O.Y. Early Nile Valley Farmers from El-Badari: Aboriginals or "European" Agro-Nostratic Immigrants? Craniometric Affinities Considered With Other Data. Journal of Black Studies. 2005, 36 (2): 191–208. S2CID 144482802. doi:10.1177/0021934704265912.

- ^ Kemp, B. 2005 "Ancient Egypt Anatomy of a Civilisation". Routledge. p. 52–60

- ^ Shirai, Noriyuki. The Archaeology of the First Farmer-Herders in Egypt: New Insights into the Fayum Epipalaeolithic. Archaeological Studies Leiden University. Leiden University Press. 2010.

- ^ Wetterstrom, W. Shaw, T.; et al , 编. Archaeology of Africa. London: Routledge. 1993: 165–226.

- ^ Rahmani, N. Le Capsien typique et le Capsien supérieur. Cambridge Monographs in Archaeology (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press). 2003, (57).

- ^ Keita, S. O. Y.; Boyce, A. J. Genetics, Egypt and History: Interpreting Geographical Patterns of a Y-Chromosome Variation. History in Africa. 2005, 32: 221–46. S2CID 163020672. doi:10.1353/hia.2005.0013.

- ^ Ehret, C; Keita, SOY; Newman, P. The Origins of Afroasiatic a response to Diamond and Bellwood (2003). Science. 2004, 306 (5702): 1680. PMID 15576591. S2CID 8057990. doi:10.1126/science.306.5702.1680c.

- ^ Ehret, Christopher. Ancient Africa: A Global History, to 300 CE. Princeton: Princeton University Press. 20 June 2023: 82–85. ISBN 978-0-691-24409-9 (英语).

- ^ Zakrzewski, Sonia R. Population continuity or population change: Formation of the ancient Egyptian state. American Journal of Physical Anthropology. April 2007, 132 (4): 501–509. PMID 17295300. doi:10.1002/ajpa.20569 (英语).

- ^ "There is no evidence, no archaeological signal, for a mass migration (settler colonization)" into Egypt from southwest Asia at the time of the writing. Core Egyptian culture was well established. A total peopling of Egypt at this time from the Near East would have meant the mass migration of Semitic speakers. The ancient Egyptian language – using the usual academic language taxonomy – is a branch within Afroasiatic with one member (not counting place of origin/urheimat is within Africa, using standard linguistic criteria based on the locale of greatest diversity, deepest branches, and least moves accounting for its five or six branches or sevem, if Ongota is counted".Template:Verify inline Keita, S. O. Y. Ideas about 'Race' in Nile Valley Histories: A Consideration of 'Racial' Paradigms in Recent Presentations on Nile Valley Africa, from 'Black Pharaohs' to Mummy Genomest. Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections. September 2022.

- ^ Wengrow, David; Dee, Michael; Foster, Sarah; Stevenson, Alice; Ramsey, Christopher Bronk. Cultural convergence in the Neolithic of the Nile Valley: a prehistoric perspective on Egypt's place in Africa. Antiquity. March 2014, 88 (339): 95–111. ISSN 0003-598X. S2CID 49229774. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00050249

(英语).

(英语).

- ^ Redford, Donald. The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press. 2001: 27–28. ISBN 978-0195102345.

- ^ "P2 (PN2) marker, within the E haplogroup, connects the predominant Y chromosome lineage found in Africa overall after the modern human left Africa. P2/M215-55 is found from the Horn of Africa up through the Nile Valley and west to the Maghreb, and P2/V38/M2 is predominant in most of infra-Saharan tropical Africa". Shomarka, Keita. Ancient Egyptian 'Origins' and 'Identity'. Ancient Egyptian society: challenging assumptions, exploring approaches. Abingdon, Oxfordshire: Routledge. 2022: 111–122. ISBN 978-0367434632.

- ^ "Moreover, the available genetic evidence – relating in particular to the M35/215 Y-chromosome lineage – also accords with just this kind of demographic history. This lineage had its origins broadly in the Horn of Africa and East Africa." Ehret, Christopher. Ancient Africa: A Global History, to 300 CE. Princeton University Press. 20 June 2023: 97. ISBN 978-0-691-24410-5 (英语).

- ^ Trombetta, B.; Cruciani, F.; Sellitto, D.; Scozzari, R. A new topology of the human Y chromosome haplogroup E1b1 (E-P2) revealed through the use of newly characterized binary polymorphisms. PLOS ONE. 2011, 6 (1): e16073. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...616073T. PMC 3017091

. PMID 21253605. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0016073

. PMID 21253605. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0016073  .

.

- ^ Cruciani, Fulvio; et al. Tracing Past Human Male Movements in Northern/Eastern Africa and Western Eurasia: New Clues from Y-Chromosomal Haplogroups E-M78 and J-M12. Molecular Biology and Evolution. June 2007, 24 (6): 1300–1311. PMID 17351267. doi:10.1093/molbev/msm049.

- ^ Anselin, Alain H. Egypt in its African context: proceedings of the conference held at the Manchester Museum, University of Manchester, 2-4 October 2009. Oxford: Archaeopress. 2011: 43–54. ISBN 978-1407307602.

- ^ Stiebing, William H. Jr.; Helft, Susan N. Ancient Near Eastern History and Culture. Taylor & Francis. 3 July 2023: 209–212. ISBN 978-1-000-88066-3 (英语).

- ^ Shaw, Ian. The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. OUP Oxford. 2003-10-23: 309. ISBN 978-0-19-160462-1 (英语).

- ^ 62.0 62.1 Gardiner, Alan. Egypt of the Pharaohs. Oxford: University Press. 1964: 388.

- ^ Redford, Donald B. Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times

. Princeton: University Press. 1992: 8. ISBN 9780691036069.

. Princeton: University Press. 1992: 8. ISBN 9780691036069.

- ^ 64.0 64.1 郭小瑞. 古埃及早期社会分层的缘起. 外国问题研究. 2023, (01): 48-59+143. doi:10.16225/j.cnki.wgwtyj.2023.01.006.

- ^ Eiwanger, Josef. Merimde Beni-salame. Bard, Kathryn A. (编). Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt

. London/New York: Routledge. 1999: 501–505. ISBN 9780415185899.

. London/New York: Routledge. 1999: 501–505. ISBN 9780415185899.

- ^ Mortensen, Bodil. el-Omari. Bard, Kathryn A. (编). Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt

. London/New York: Routledge. 1999: 592–594. ISBN 9780415185899.

. London/New York: Routledge. 1999: 592–594. ISBN 9780415185899.

- ^ El-Omari. EMuseum. Mankato: Minnesota State University. (原始内容存档于15 June 2010).

- ^ "Maadi", University College London.

- ^ Mark, Joshua J. Predynastic Period in Egypt. World History Encyclopedia. 18 January 2016 [2017-11-14].

- ^ "Maadi", University College London.

- ^ Seeher, Jürgen. Ma'adi and Wadi Digla

. Bard, Kathryn A. (编). Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt. London/New York: Routledge: 455–458. 1999. ISBN 9780415185899.

. Bard, Kathryn A. (编). Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt. London/New York: Routledge: 455–458. 1999. ISBN 9780415185899.

- ^ Mączyńska, Agnieszka. On the Transition Between the Neolithic and Chalcolithic in Lower Egypt and the Origins of the Lower Egyptian Culture: a Pottery Study (PDF). Desert and the Nile. Prehistory of the Nile Basin and the Sahara. 2018. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于March 27, 2023).

- ^ 73.0 73.1 73.2 Gardiner, Alan, Egypt of the Pharaohs (Oxford: University Press, 1964), p. 389.

- ^ Grimal, Nicolas. A History of Ancient Egypt. p.35. Librairie Arthéme Fayard, 1988.

- ^ Excell, Karen. Egypt in its African context: proceedings of the conference held at the Manchester Museum, University of Manchester, 2–4 October 2009. Oxford: Archaeopress. 2011: 43–54. ISBN 978-1407307602.

- ^ Williams, Bruce. The Qustul Incense Burner and the Case for a Nubian Origin of Ancient Egyptian Kingship. Celenko, Theodore (编). Egypt in Africa. Indianapolis, Indiana: Indianapolis Museum of Art. 1996: 95–97. ISBN 978-0936260648.

- ^ Shaw, Ian (编). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press. 2000: 479. ISBN 0-19-815034-2.

- ^ 78.0 78.1 Grimal, Nicolas. A History of Ancient Egypt. p.24. Librairie Arthéme Fayard, 1988

- ^ Gardiner, Alan, Egypt of the Pharaohs (Oxford: University Press, 1964), p. 391.

- ^ Newell, G. D. (2012). "A re-examination of the Badarian Culture". MA thesis.

- ^ "When Mahalanobis D2 was used,the Naqadan and Badarian Predynastic samples exhibited more similarity to Nubian, Tigrean, and some more southern series than to some mid- to late Dynasticseries from northern Egypt (Mukherjee et al., 1955). The Badarian have been found to be very similar to a Kerma sample (Kushite Sudanese), using both the Penrose statistic (Nutter, 1958) and DFA of males alone (Keita, 1990). Furthermore, Keita considered that Badarian males had a southern modal phenotype, and that together with a Naqada sample, they formed a southern Egyptian cluster as tropical variants together with a sample from Kerma". Zakrzewski, Sonia R. Population continuity or population change: Formation of the ancient Egyptian state. American Journal of Physical Anthropology. April 2007, 132 (4): 501–509. PMID 17295300. doi:10.1002/ajpa.20569 (英语).

- ^ Keita, S. O. Y. Early Nile Valley Farmers From El-Badari: Aboriginals or 'European' Agro-Nostratic Immigrants? Craniometric Affinities Considered With Other Data. Journal of Black Studies. 2005, 36 (2): 191–208. ISSN 0021-9347. JSTOR 40034328. S2CID 144482802. doi:10.1177/0021934704265912.

- ^ Godde, Kanya. A biological perspective of the relationship between Egypt, Nubia, and the Near East during the Predynastic period. [20 February 2022].

- ^ S. O. Y., Keita; A. J., Boyce. Temporal variation in phenetic affinity of early Upper Egyptian male cranial series. Human Biology. 2008, 80 (2): 141–159. ISSN 0018-7143. PMID 18720900. S2CID 25207756. doi:10.3378/1534-6617(2008)80[141:TVIPAO]2.0.CO;2 (英语).

- ^ "Keita (1992), using craniometrics, discovered that the Badarian series is distinctly different from the later Egyptian series, a conclusion that is mostly confirmed here. In the current analysis, the Badari sample more closely clusters with the Naqada sample and the Kerma sample". Godde, K. An examination of Nubian and Egyptian biological distances: support for biological diffusion or in situ development?. Homo: Internationale Zeitschrift für die vergleichende Forschung am Menschen. 2009, 60 (5): 389–404. ISSN 1618-1301. PMID 19766993. doi:10.1016/j.jchb.2009.08.003.

- ^ Ehret, Christopher. Ancient Africa: A Global History, to 300 CE. Princeton: Princeton University Press. 20 June 2023: 84–85. ISBN 978-0-691-24409-9 (英语).

- ^ Strohaul, Eugene. Anthropology of the Egyptian Nubian Men - Strouhal - 2007 - ANTHROPOLOGIE (PDF). Puvodni.MZM.cz: 115.

- ^ Keita, S. O. Y. Early Nile Valley Farmers From El-Badari: Aboriginals or 'European' Agro-Nostratic Immigrants? Craniometric Affinities Considered With Other Data. Journal of Black Studies. November 2005, 36 (2): 191–208. ISSN 0021-9347. S2CID 144482802. doi:10.1177/0021934704265912 (英语).

- ^ 89.0 89.1 89.2 Haddow, Scott Donald. Dental Morphological Analysis of Roman Era Burials from the Dakhleh Oasis, Egypt. Institute of Archaeology, University College London. January 2012 [2 June 2017].

- ^ "When Mahalanobis D2 was used, the Naqadan and Badarian Predynastic samples exhibited more similarity to Nubian, Tigrean, and some more southern series than to some mid- to late Dynasticseries from northern Egypt (Mukherjee et al., 1955). The Badarian have been found to be very similar to a Kerma sample (Kushite Sudanese), using both the Penrose statistic (Nutter, 1958) and DFA of males alone (Keita, 1990). Furthermore, Keita considered that Badarian males had a southern modal phenotype, and that together with a Naqada sample, they formed a southern Egyptian cluster as tropical variants together with a sample from Kerma". Zakrzewski, Sonia R. Population continuity or population change: Formation of the ancient Egyptian state. American Journal of Physical Anthropology. April 2007, 132 (4): 501–509. PMID 17295300. doi:10.1002/ajpa.20569 (英语).

- ^ Keita, S. O. Y. Studies and Comments on Ancient Egyptian Biological Relationships. History in Africa. 1993, 20: 129–154. ISSN 0361-5413. JSTOR 3171969. S2CID 162330365. doi:10.2307/3171969.

- ^ Keita, Shomarka. Analysis of Naqada Predynastic Crania: a brief report (PDF). 1996 [22 February 2022]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于5 December 2022).

- ^ Godde, K. An examination of Nubian and Egyptian biological distances: support for biological diffusion or in situ development?. Homo: Internationale Zeitschrift für die Vergleichende Forschung am Menschen. 2009, 60 (5): 389–404. ISSN 1618-1301. PMID 19766993. doi:10.1016/j.jchb.2009.08.003.

- ^ Godde, Kanya. A biological perspective of the relationship between Egypt, Nubia, and the Near East during the Predynastic period. Egypt at its Origins 6: Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference "Origin of the State. Predynastic and Early Dynastic Egypt". Vienna: Peeters. 2020. 已忽略未知参数

|orig-date=(帮助) - ^ Ehret, Christopher. Ancient Africa: A Global History, to 300 CE. Princeton: Princeton University Press. 20 June 2023: 84–85. ISBN 978-0-691-24409-9 (英语).

- ^ Keita, Shomarka. Analysis of Naqada Predynastic Crania: a brief report (1996) (PDF). [2022-02-22]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2022-12-05).

- ^ Lovell, Nancy; Prowse, Tracy. Concordance of cranial and dental morphological traits and evidence for endogamy in ancient Egypt. American Journal of Physical Anthropology. October 1996, 101 (2): 237–246. PMID 8893087. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-8644(199610)101:2<237::AID-AJPA8>3.0.CO;2-Z.

Table 3 presents the MMD data for Badari, Qena, and Nubia in addition to Naqada and shows that these samples are all significantly different from each other. ... 1) the Naqada samples are more similar to each other than they are to the samples from the neighbouring Upper Egyptian or Lower Nubian sites and 2) the Naqada samples are more similar to the Lower Nubian protodynastic sample than they are to the geographically more proximate Egyptian samples.

- ^ Lovell, Nancy; Prowse, Tracy. Concordance of cranial and dental morphological traits and evidence for endogamy in ancient Egypt. American Journal of Physical Anthropology. October 1996, 101 (2): 237–246. PMID 8893087. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-8644(199610)101:2<237::AID-AJPA8>3.0.CO;2-Z.

... the Naqada samples are more similar to each other than they are to the samples from the neighbouring Upper Egyptian or Lower Nubian sites ...

- ^ Ehret, Christopher. Ancient Africa: A Global History, to 300 CE. Princeton: Princeton University Press. 20 June 2023: 82–85, 97. ISBN 978-0-691-24409-9 (英语).

- ^ Shaw, Ian (编). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press. 2000: 479. ISBN 0-19-815034-2.

- ^ Grimal, Nicolas. A History of Ancient Egypt. p.24. Librairie Arthéme Fayard, 1988

- ^ 102.0 102.1 Gardiner, Alan, Egypt of the Pharaohs (Oxford: University Press, 1964), p. 390.

- ^ 103.0 103.1 Grimal, Nicolas. A History of Ancient Egypt. p. 28. Librairie Arthéme Fayard, 1988

- ^ Redford, Donald B. (1992). Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times. Princeton: University Press, p. 7.

- ^ Gardiner, Alan (1964), Egypt of the Pharaohs. Oxford: University Press, p. 393.

- ^ Newell, G. D., "The Relative chronology of PNC I" (Academia.Edu: 2012)

- ^ Shaw, Ian (编). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press. 2000: 479. ISBN 0-19-815034-2.

- ^ 108.0 108.1 108.2 108.3 108.4 108.5 108.6 108.7 Redford, Donald B. Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times. (Princeton: University Press, 1992), p. 16.

- ^ 109.0 109.1 Gardiner, Alan, Egypt of the Pharaohs (Oxford: University Press, 1964), p. 390.

- ^ 110.0 110.1 Redford, Donald B. Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times. (Princeton: University Press, 1992), p. 17.

- ^ 111.0 111.1 Gardiner, Alan, Egypt of the Pharaohs (Oxford: University Press, 1964), p. 391.

- ^ 112.0 112.1 Grimal, Nicolas. A History of Ancient Egypt. p. 28. Librairie Arthéme Fayard, 1988

- ^ 113.0 113.1 Site officiel du musée du Louvre. cartelfr.louvre.fr.

- ^ Cooper, Jerrol S. The Study of the Ancient Near East in the Twenty-first Century: The William Foxwell Albright Centennial Conference. Eisenbrauns. 1996: 10–14. ISBN 9780931464966 (英语).

- ^ Shaw, Ian & Nicholson, Paul, The Dictionary of Ancient Egypt (London: British Museum Press, 1995), p. 109.

- ^ Redford, Donald B. Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times. (Princeton: University Press, 1992), p. 18.

- ^ 117.0 117.1 117.2 Redford, Donald B. Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times. (Princeton: University Press, 1992), p. 22.

- ^ Redford, Donald B. Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times. (Princeton: University Press, 1992), p. 20.

- ^ Shaw, Ian (编). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press. 2000: 479. ISBN 0-19-815034-2.

- ^ Naqada III. Faiyum.com. [1 May 2012].

- ^ Maadi Culture. University College London. [3 April 2018].

- ^ "There is now a sufficient body of evidence from modern studies of skeletal remains to indicate that the ancient Egyptians, especially southern Egyptians, exhibited physical characteristics that are within the range of variation for ancient and modern indigenous peoples of the Sahara and tropical Africa. The distribution of population characteristics seems to follow a clinal pattern from south to north, which may be explained by natural selection as well as gene flow between neighboring populations. In general, the inhabitants of Upper Egypt and Nubia had the greatest biological affinity to people of the Sahara and more southerly areas". Lovell, Nancy C. Egyptians, physical anthropology of. Bard, Kathryn A.; Shubert, Steven Blake (编). Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt. London: Routledge: 328–331. 1999. ISBN 0415185890.

- ^ Lovell, Nancy C. Egyptians, physical anthropology of (PDF). Bard, Kathryn A.; Shubert, Steven Blake (编). Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt. London: Routledge: 328–331. 1999. ISBN 0415185890.

- ^ Slayman, Andrew L., Neolithic Skywatchers, Archaeological Institute of America, May 27, 1998

- ^ Wendorf, Fred; Schild, Romuald, Late Neolithic megalithic structures at Nabta Playa (Sahara), southwestern Egypt, Comparative Archaeology Web, November 26, 2000, (原始内容存档于August 6, 2011)

- ^ Margueron, Jean-Claude. Le Proche-Orient et l'Égypte antiques. Hachette Éducation. 2012: 380. ISBN 9782011400963 (法语).

- ^ Wendorf, Fred; Schild, Romuald. Holocene Settlement of the Egyptian Sahara: Volume 1: The Archaeology of Nabta Playa. Springer Science & Business Media. 2013: 51–53. ISBN 9781461506539 (英语).

- ^ Wendorf, Fred. Holocene settlement of the Egyptian Sahara. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers. 2001: 489–502. ISBN 978-0-306-46612-0.

- ^ McKim Malville, J. Astronomy at Nabta Playa, Southern Egypt. Handbook of Archaeoastronomy and Ethnoastronomy. Springer. 2015: 1080–1090. ISBN 978-1-4614-6140-1. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-6141-8_101.

- ^ Ehret, Christopher. Ancient Africa: A Global History, to 300 CE. Princeton University Press. 20 June 2023: 107. ISBN 978-0-691-24409-9 (英语).

- ^ Malville, J. McKim, Astronomy at Nabta Playa, Egypt, Ruggles, C.L.N. (编), Handbook of Archaeoastronomy and Ethnoastronomy 2, New York: Springer Science+Business Media: 1079–1091, 2015, ISBN 978-1-4614-6140-1

- ^ Belmonte, Juan Antonio, Ancient Egypt, Ruggles, Clive; Cotte, Michel (编), Heritage Sites of Astronomy and Archaeoastronomy in the context of the UNESCO World Heritage Convention: A Thematic Study, Paris: International Council on Monuments and Sites/International Astronomical Union: 119–129, 2010, ISBN 978-2-918086-07-9

- ^ linen fragment. Digitalegypt.ucl.ac.uk. [1 May 2012].

- ^ Shaw (2000), p. 61

- ^ Brooks, Nick. Cultural responses to aridity in the Middle Holocene and increased social complexity. Quaternary International. 2006, 151 (1): 29–49. Bibcode:2006QuInt.151...29B. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2006.01.013.

- ^ "Iron beads were worn in Egypt as early as 4000 B.C., but these were of meteoric iron, evidently shaped by the rubbing process used in shaping implements of stone", quoted under the heading "Columbia Encyclopedia: Iron Age" at Iron Age, Answers.com. Also, see History of ferrous metallurgy#Meteoric iron—"Around 4000 BC small items, such as the tips of spears and ornaments, were being fashioned from iron recovered from meteorites" – attributed to R. F. Tylecote, A History of Metallurgy (2nd edition, 1992), p. 3.