草稿:風箏

風箏是一種比空氣重或比空氣輕的繫繩飛行器,其表面與空氣發生反應,以產生升力和阻力。風箏由翼、線和錨組成,通常使用韁繩和尾巴來引導風箏表面,讓風可以將風箏舉起。[1] Some kite designs do not need a bridle; box kites can have a single attachment point. A kite may have fixed or moving anchors that can balance the kite. The name is derived from the kite, the hovering bird of prey.[2]

The lift that sustains the kite in flight is generated when air moves around the kite's surface, producing low pressure above and high pressure below the wings.[3] The interaction with the wind also generates horizontal drag along the direction of the wind. The resultant force vector from the lift and drag force components is opposed by the tension of one or more of the lines or tethers to which the kite is attached.[4] The anchor point of the kite line may be static or moving (e.g., the towing of a kite by a running person, boat, free-falling anchors as in paragliders and fugitive parakites[5][6] or vehicle).[7][8]

The same principles of fluid flow apply in liquids, so kites can be used in underwater currents.[9][10] Paravanes and otter boards operate underwater on an analogous principle.

Man-lifting kites were made for reconnaissance, entertainment and during development of the first practical aircraft, the biplane.

Kites have a long and varied history and many different types are flown individually and at festivals worldwide. Kites may be flown for recreation, art or other practical uses. Sport kites can be flown in aerial ballet, sometimes as part of a competition. Power kites are multi-line steerable kites designed to generate large forces which can be used to power activities such as kite surfing, kite landboarding, kite buggying and snow kiting.

歷史[編輯]

公元前5世紀,風箏被認為是中國哲學家墨子和魯班的發明。製作風箏的理想材料很容易獲得,包括用作風箏主體的絲綢、用於牽引風箏放飛的絲線和有彈性的竹子構成堅固輕盈的骨架。公元549年,人們開始放飛紙風箏,當時風箏被用來作為求救兵的通信。古代中國文獻記載,風箏被用來測量距離、測試風向、舉升人員、發信號和軍事行動中的通信。已知最早的中國風箏是扁平形狀(而不是弓形),並且通常是矩形。風箏上裝飾吉祥圖案,有些裝有弦和哨,可以在飛行時發出聲響。[11][12][13]

After its introduction into India, the kite further evolved into the fighter kite, known as the patang in India, where thousands are flown every year on festivals such as Makar Sankranti.[14]

Kites were known throughout Polynesia, as far as New Zealand, with the assumption being that the knowledge diffused from China along with the people. Anthropomorphic kites made from cloth and wood were used in religious ceremonies to send prayers to the gods.[15] Polynesian kite traditions are used by anthropologists to get an idea of early "primitive" Asian traditions that are believed to have at one time existed in Asia.[16]

Kites were late to arrive in Europe, although windsock-like banners were known and used by the Romans. Stories of kites were first brought to Europe by Marco Polo towards the end of the 13th century, and kites were brought back by sailors from Japan and Malaysia in the 16th and 17th centuries.[17][18] Konrad Kyeser described dragon kites in Bellifortis about 1400 AD.[19] Although kites were initially regarded as mere curiosities, by the 18th and 19th centuries they were being used as vehicles for scientific research.[17]

1752年,本傑明·富蘭克林發表一篇風箏實驗的論文,以證明是由電引起的閃電。

風箏在萊特兄弟和其他人的研究中也發揮重要作用,促使他們在1800年代末發明第一架飛機,以及幾種不同設計的載人風箏同時被開發出來。1860年至1910年左右,這段時期成為歐洲「風箏的黃金時代」。[20]

In the 20th century, many new kite designs are developed. These included Eddy's tailless diamond, the tetrahedral kite, the Rogallo wing, the sled kite, the parafoil, and power kites.[21] Kites were used for scientific purposes, especially in meteorology, aeronautics, wireless communications and photography. The Rogallo wing was adapted for stunt kites and hang gliding and the parafoil was adapted for parachuting and paragliding.

The rapid development of mechanically powered aircraft diminished interest in kites. World War II saw a limited use of kites for military purposes (survival radio, Focke Achgelis Fa 330, military radio antenna kites).

Kites are now mostly used for recreation. Lightweight synthetic materials (ripstop nylon, plastic film, carbon fiber tube and rod) are used for kite making. Synthetic rope and cord (nylon, polyethylene, kevlar and dyneema) are used as bridle and kite line.

材料[編輯]

Designs often emulate flying insects, birds, and other beasts, both real and mythical. The finest Chinese kites are made from split bamboo (usually golden bamboo), covered with silk, and hand painted. On larger kites, clever hinges and latches allow the kite to be disassembled and compactly folded for storage or transport. Cheaper mass-produced kites are often made from printed polyester rather than silk.

Tails are used for some single-line kite designs to keep the kite's nose pointing into the wind. Spinners and spinsocks can be attached to the flying line for visual effect. There are rotating wind socks which spin like a turbine. On large display kites these tails, spinners and spinsocks can be 50英尺(15公尺) long or more.

Modern aerobatic kites use two or four lines to allow fine control of the kite's angle to the wind. Traction kites may have an additional line to de-power the kite and quick-release mechanisms to disengage flyer and kite in an emergency.

實用[編輯]

風箏除了是一種娛樂遊戲,也被用於人類飛行、軍事應用、科學與氣象研究、攝影、升降無線電天線、發電、空氣動力學實驗等領域。

軍事用途[編輯]

Kites have been used for military purposes in the past, such as signaling, delivery of ammunition, and for observation, both by lifting an observer above the field of battle and by using kite aerial photography.

Kites were first used in warfare by the Chinese.[22] During the Song dynasty the Fire Crow, a kite carrying incendiary powder, a fuse, and a burning stick of incense was developed as a weapon.[23]

According to Samguk Sagi, in 647 Kim Yu-sin, a Korean general of Silla rallied his troops to defeat rebels by using flaming kites which also scared the enemy.[24]

Russian chronicles mention Prince Oleg of Novgorod use of kites during the siege of Constantinople in 906: "and he crafted horses and men of paper, armed and gilded, and lifted them into the air over the city; the Greeks saw them and feared them".[25]

Walter de Milemete's 1326 De nobilitatibus, sapientiis, et prudentiis regum treatise depicts a group of knights flying kite laden with a black-powder filled firebomb over the wall of city.[26]

Kites were also used by Admiral Yi of the Joseon Dynasty (1392–1910) of Korea. During the Japanese invasions of Korea (1592–1598), Admiral Yi commanded his navy using kites. His kites had specific markings directing his fleet to perform various orders.[27]

In the modern era the British Army used kites to haul human lookouts into the air for observation purposes, using the kites developed by Samuel Franklin Cody. Barrage kites were used to protect shipping during the Second World War.[28][29] Kites were also used for anti-aircraft target practice.[30] Kites and kytoons were used for lofting communications antenna.[31] Submarines lofted observers in rotary kites.[32]

Palestinians from the Gaza Strip have flown firebomb kites over the Israel–Gaza barrier, setting fires on the Israeli side of the border,[33][34][35][36] hundreds of dunams of Israeli crop fields were burned by firebomb kites launched from Gaza, with an estimated economic loss of several millions of shekels.[37]

科學與氣象學[編輯]

風箏曾經用於科學目的,例如本傑明·富蘭克林利用風箏,證明閃電是電的著名實驗。風箏是傳統航空器的前身,在早期飛行器的發展中發揮着重要作用,亞歷山大·格雷厄姆·貝爾試驗過非常大的載人風箏,萊特兄弟和勞倫斯·哈格雷夫也做過類似的實驗。風箏在提升科學儀器以測量大氣條件,從而進行天氣預報方面發揮過歷史性作用,於1847年在喬城天文台,弗朗西斯·羅納德和威廉·拉德克利夫·伯特描述過一種非常穩定的風箏,被試用於支撐高空自記錄氣象儀器。[38]

無線電天線和燈標[編輯]

Kites can be used for radio purposes, by kites carrying antennas for MF, LF or VLF-transmitters. This method was used for the reception station of the first transatlantic transmission by Marconi. Captive balloons may be more convenient for such experiments, because kite-carried antennas require a lot of wind, which may be not always possible with heavy equipment and a ground conductor. It must be taken into account during experiments, that a conductor carried by a kite can lead to high voltage toward ground, which can endanger people and equipment, if suitable precautions (grounding through resistors or a parallel resonant circuit tuned to transmission frequency) are not taken.

Kites can be used to carry light effects such as lightsticks or battery powered lights.

風箏牽引[編輯]

風箏可用於順風拉動人員和車輛,高效的翼型風箏(如動力風箏)也可用於逆風航行。其原理與帆船相同,前提是地面或水中的橫向力,可以像傳統帆船的龍骨、中心板、輪和冰葉一樣重新定向。在過去多年裡,一些風箏牽引運動開始變得流行,例如風箏越野車、風箏陸上滑板、風箏划船和風箏衝浪,以及近年出現的風箏滑雪。

Kite sailing opens several possibilities not available in traditional sailing:

- Wind speeds are greater at higher altitudes

- Kites may be maneuvered dynamically which increases the force available dramatically

- There is no need for mechanical structures to withstand bending forces; vehicles or hulls can be very light or dispensed with all together

水下風箏[編輯]

Underwater kites are now being developed to harvest renewable power from the flow of water.[39][40] A kite was used in minesweeping operations from the First World War: this was a foil "attached to a sweep-wire submerging it to the requisite depth when it is towed over a minefield" (OED, 2021). See also paravane.

風箏釣魚[編輯]

Kite fishing is a fishing technique. It involves a kite from which a drop line hangs, attached to a lure or bait. The kite is flown over the surface of a body of water, and the bait floats near the waterline until taken by a fish. The kite then drops immediately, signaling to the fisherman that the bait has been taken, and the fish can then be hauled in. Kites can provide boatless fishermen access to waters that would otherwise be available only to boats. Similarly, for boat owners, kites provide a way to fish in areas where it is not safe to navigate - such as shallows or coral reef.

文化用途[編輯]

風箏節是世界各地流行的娛樂節日,包括當地傳統的風箏遊戲活動,以及國際的風箏交流活動,吸引不同國家的風箏愛好者,展示其獨特的風箏藝術。許多國家都有風箏博物館,重點關注風箏的發展歷史,保留該國的風箏傳統。[41]

亞洲[編輯]

Kite flying is popular in many Asian countries, where it often takes the form of "kite fighting", in which participants try to snag each other's kites or cut other kites down.[42] Fighter kites are usually small, flattened diamond-shaped kites made of paper and bamboo. Tails are not used on fighter kites so that agility and maneuverability are not compromised.

In Afghanistan, kite flying is a popular game, and is known in Dari as Gudiparan Bazi. Some kite fighters pass their strings through a mixture of ground glass powder and glue, which is legal. The resulting strings are very abrasive and can sever the competitor's strings more easily. The abrasive strings can also injure people. During the Taliban rule in Afghanistan, kite flying was banned, among various other recreations.

In Pakistan, kite flying is often known as Gudi-Bazi or Patang-bazi. Although kite flying is a popular ritual for the celebration of spring festival known as Jashn-e-Baharaan (lit. Spring Festival) or Basant, kites are flown throughout the year. Kite fighting is a very popular pastime all around Pakistan, but mostly in urban centers across the country (especially Lahore). The kite fights are at their highest during the spring celebrations and the fighters enjoy competing with rivals to cut-loose the string of the others kite, popularly known as "Paecha". During the spring festival, kite flying competitions are held across the country and the skies are colored with kites. When a competitor succeeds in cutting another's kite loose, shouts of 'wo kata' ring through the air. Cut kites are reclaimed by chasing after them. This is a popular ritual, especially among the country's youth, and is depicted in the 2007 film The Kite Runner (although that story is based in neighboring Afghanistan). Kites and strings are a big business in the country and several different types of string are used, including glass-coated, metal, and tandi. Kite flying was banned in Punjab, India due to more than one motorcyclist death caused by glass-coated or metal kite strings.[43] Kup, Patang, Guda, and Nakhlaoo are some of the popular kite brands; they vary in balance, weight and speed.

In Indonesia kites are flown as both sport and recreation. One of the most popular kite variants is from Bali. Balinese kites are unique and they have different designs and forms; birds, butterflies, dragons, ships, etc. In Vietnam, kites are flown without tails. Instead small flutes are attached allowing the wind to "hum" a musical tune. There are other forms of sound-making kites. In Bali, large bows are attached to the front of the kites to make a deep throbbing vibration, and in Malaysia, a row of gourds with sound-slots are used to create a whistle as the kite flies. Malaysia is also home to the Kite Museum in Malacca.[44]

Kite are also popular in Nepal, especially in hilly areas and among the Pahadi and Newar communities, although people also fly kites in Terai areas. Unlike India, people in Nepal fly kites in August – September period and is more popular in time of Dashain.[45]

Kites are very popular in India, with the states of Gujarat, Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, Haryana and Punjab notable for their kite fighting festivals. Highly maneuverable single-string paper and bamboo kites are flown from the rooftops while using line friction in an attempt to cut each other's kite lines, either by letting the cutting line loose at high speed or by pulling the line in a fast and repeated manner. During the Indian spring festival of Makar Sankranti, near the middle of January, millions of people fly kites all over northern India. Kite flying in Hyderabad starts a month before this, but kite flying/fighting is an important part of other celebrations, including Republic Day, Independence Day, Raksha Bandhan, Viswakarma Puja day in late September and Janmashtami. An international kite festival is held every year before Uttarayan for three days in Vadodara, Surat and Ahmedabad.

Kites have been flown in China since ancient times. Weifang is home to the largest kite museum in the world.[46][47] It also hosts an annual international kite festival on the large salt flats south of the city. There are several kite museums in Japan, UK, Malaysia, Indonesia, Taiwan, Thailand and the USA. In the pre-modern period, Malays in Singapore used kites for fishing.[48]

In Japan, kite flying is traditionally a children's play in New Year holidays and in the Boys' Festival in May. In some areas, there is a tradition to celebrate a new boy baby with a new kite (祝い凧). There are many kite festivals throughout Japan. The most famous one is "Yōkaichi Giant Kite Festival" in Higashiōmi, Shiga, which started in 1841.[49] The largest kite ever built in the festival is 62英尺(19公尺) wide by 67英尺(20公尺) high and weighs 3,307英磅(1,500公斤).[50] In the Hamamatsu Kite Festival in Hamamatsu, Shizuoka, more than 100 kites are flown in the sky over the Nakatajima Sand Dunes, one of the three largest sand dunes in Japan, which overlooks the Enshunada Sea.[51] Parents who have a new baby prepare a new kite with their baby's name and fly it in the festival.[52] These kites are traditional ones made from bamboo and paper.

-

Making a traditional Wau jala budi kite in Malaysia. The bamboo frame is covered with plain paper and then decorated with multiple layers of shaped paper and foil.

-

Various Balinese kites is on display in front of a store in Ubud, Bali, Indonesia

-

A kite shop in Lucknow, India

-

Traditional Japanese kites

歐洲[編輯]

In Greece and Cyprus, flying kites is a tradition for Clean Monday, the first day of Lent. In the British Overseas Territory of Bermuda, traditional Bermuda kites are made and flown at Easter, to symbolise Christ's ascent. In Fuerteventura a kite festival is usually held on the weekend nearest to 8 November lasting for 3 days.

波利尼西亞[編輯]

Polynesian traditional kites are sometimes used at ceremonies and variants of traditional kites for amusement. Older pieces are kept in museums. These are treasured by the people of Polynesia.

-

Māori kite

-

Launch of ram-air inflated Peter Lynn single-line kite, shaped like an octopus and 90英尺(27公尺) long

南美洲[編輯]

In Brazil, flying a kite is a very popular leisure activity for children, teenagers and even young adults. Mostly these are boys, and it is overwhelmingly kite fighting a game whose goal is to maneuver their own kites to cut the other persons' kites' strings during flight, and followed by kite running where participants race through the streets to take the free-drifting kites. As in other countries with similar traditions, injuries are common and motorcyclists in particular need to take precautions.[53]

In Chile, kites are very popular, especially during Independence Day festivities (September 18). In Peru, kites are also very popular. There are kite festivals in parks and beaches mostly on August.

In Colombia, kites can be seen flown in parks and recreation areas during August which is calles as windy. It is during this month that most people, especially the young ones would fly kites.

In Guyana, kites are flown at Easter, an activity in which all ethnic and religious groups participate. Kites are generally not flown at any other time of year. Kites start appearing in the sky in the weeks leading up to Easter and school children are taken to parks for the activity. It all culminates in a massive airborne celebration on Easter Monday especially in Georgetown, the capital, and other coastal areas. The history of the practice is not entirely clear but given that Easter is a Christian festival, it is said that kite flying is symbolic of the Risen Lord. Moore[54] describes the phenomenon in the 19th century as follows:

A very popular Creole pastime was the flying of kites. Easter Monday, a public holiday, was the great kite-flying day on the sea wall in Georgetown and on open lands in villages. Young and old alike, male and female, appeared to be seized by kite-flying mania. Easter 1885 serves as a good example. "The appearance of the sky all over Georgetown, but especially towards the Sea Wall, was very striking, the air being thick with kites of all shapes and sizes, covered with gaily coloured paper, all riding bravely on the strong wind.

——(His quotation is from a letter to The Creole newspaper of December 29, 1858.)

The exact origins of the practice of kite flying (exclusively) at Easter are unclear. Bridget Brereton and Kevin Yelvington[55] speculate that kite flying was introduced by Chinese indentured immigrants to the then colony of British Guiana in the mid 19th century. The author of an article in the Guyana Chronicle newspaper of May 6, 2007 is more certain:

Kite flying originated as a Chinese tradition to mark the beginning of spring. However, because the plantation owners were suspicious of the planter class (read "plantation workers"), the Chinese claimed that it represented the resurrection of Jesus Christ. It was a clever argument, as at that time, Christians celebrated Easter to the glory of the risen Christ. The Chinese came to Guyana from 1853–1879.[56]

世界紀錄[編輯]

吉尼斯世界紀錄大全有許多涉及風箏的世界紀錄項目,[57] 其中世界上最大風箏是稱為「科威特國旗」的充氣單線風箏,放飛在空中至少20分鐘。[58]

The single-kite altitude record is held by a triangular-box delta kite. On 23 September 2014 a team led by Robert Moore, flew a 129平方英尺(12平方公尺) kite to 16,009英尺(4,880公尺) above ground level.[59] The record altitude was reached after eight series of attempts over a ten-year period from a remote location in western New South Wales, Australia. The 9.2英尺(3公尺) tall and 19.6英尺(6公尺) wide Dunton-Taylor delta kite's flight was controlled by a winch system using 40,682英尺(12,400公尺) of ultra high strength Dyneema line. The flight took about eight hours from ground and return. The height was measured with on-board GPS telemetry transmitting positional data in real time to a ground-based computer and also back-up GPS data loggers for later analysis.[60]

流行文化[編輯]

- The Kite Runner, a 2005 novel by Khaled Hosseini dramatizes the role of kite fighting in pre-war Kabul.

- The Peanuts cartoon character Charlie Brown was often depicted having flown his kite into a tree as a metaphor for life's adversities.

- "Let's Go Fly a Kite" is a song from the Mary Poppins film and musical.

- In the Disney animated film Mulan, kites are flown in the parade.

- In the film Shooter, a kite is used to show the wind direction and wind velocity.

- "Kite" is a 1978 song celebrating kite flying and appears on Kate Bush's first album, The Kick Inside.

一般安全問題[編輯]

放飛風箏存在一些安全問題,例如:風箏線可能會撞擊並纏繞在電線上,導致區域停電,並有可能導致觸電的危險;當在暴風雨天氣時,沾濕的風箏線可以充當靜電和閃電的導體;大面積或強大升力的風箏,可能將放風箏的人拖離地面或拖入其他物體。在多數城市地區,風箏的飛行高度通常有上限,以防止風箏和風箏線侵犯直升機和輕型飛機的空域;鬥風箏使用沾有玻璃粉的風箏線,也有可能造成人命傷亡,例如:2016年8月印度發生三名觀眾在不同事件中喪生。

埃及政府出於安全和國家安全考慮,於 2020年7月禁止放風箏,並在開羅查獲369隻風箏,在亞歷山大查獲99隻風箏,並對部分民眾處以罰款。[61]

畫廊[編輯]

-

This delta kite has a keel instead of a bridle

-

Giant Japanese kite launched, 2019

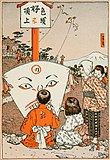

-

Kites fly on top of the Mitsui Store where the craftsmen are working on top of the roof, print by Hokusai

-

Hiroshige II Enshū Akiha (1859)

-

Illustration from the book Story of the mince pie by Josephine Scribner Gates, (1916)

參考資料[編輯]

- ^ Eden, Maxwell. The Magnificent Book of Kites: Explorations in Design, Construction, Enjoyment & Flight. New York: Sterling Publishing Company, Inc. 2002: 18. ISBN 9781402700941.

- ^ kite | Etymology, origin and meaning of kite by etymonline. Etymonline.com. [14 December 2021].

- ^ Beginner's Guide to Aeronautics. NASA. [2012-10-03]. (原始內容存檔於2015-03-25).

- ^ Flying High, Down Under. [14 December 2021]. (原始內容存檔於1 December 2008).

- ^ Woglom, Gilbert Totten. Parakites: A treatise on the making and flying of tailless kites for scientific purposes and for recreation. Putnam. 1896. OCLC 2273288. OL 6980132M.

- ^ Science in the Field: Ben Balsley, CIRES Scientist in the Field Gathering atmospheric dynamics data using kites. Kites are anchored to boats on the Amazon River employed to sample levels of certain gases in the air.. [14 December 2021]. (原始內容存檔於14 March 2008).

- ^ The Bachstelze Article describes the Fa-330 Rotary Wing Kite towed by its mooring to the submarine. The kite was a man-lifter modeled after the autogyro principle. Uboat.net. [2012-10-03].

- ^ Kite Fashions: Above, Below, Sideways. Expert kite fliers sometimes tie a flying kite to a tree to have the kite fly for days on end. (PDF). [14 December 2021]. (原始內容 (PDF)存檔於23 July 2011).

- ^ Underwater kiting. 2lo.de. [2012-10-03].

- ^ Hydro kite angling device Jason C. Hubbart. [2012-10-03].

- ^ Needham (1965), Science and Civilisation in China, p. 576–580

- ^ Sarak, Sim; Yarin, Cheang. Khmer Kites. Cambodia: Ministry of Culture and Fine Arts. 2002. ASIN B005VDYAAW.

- ^ Kite Flying for Fun and Science, 1907, The New York Times.

- ^ Tripathi, Piyush Kumar. Kite fights to turn skies colourful on Makar Sankranti - Professional flyers to showcase flying skills; food lovers can relish delicacies at snack huts. The Telegraph (Calcutta, India). 7 January 2012. (原始內容存檔於August 13, 2013).

- ^ Tarlton, John. Ancient Maori Kites. [19 October 2011]. (原始內容存檔於15 October 2011).

- ^ Chadwick, Nora K. The Kite: A Study in Polynesian Tradition. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute. July 1931, 61: 455–491. ISSN 0307-3114. JSTOR 2843932. doi:10.2307/2843932.

- ^ 17.0 17.1 Anon. Kite History: A Simple History of Kiting. G-Kites. [20 June 2010]. (原始內容存檔於29 May 2010).

- ^ Needham (1965), Science and Civilisation in China, p. 580

- ^ Ley, Willy. Dragons and Hot-Air Balloons. For Your Information. Galaxy Science Fiction. December 1962: 79–89.

- ^ Archived copy (PDF). [2018-06-12]. (原始內容 (PDF)存檔於2020-06-30).

- ^ History of Kites. [18 April 2012]. (原始內容存檔於26 April 2012). 已忽略未知參數

|df=(幫助) - ^ Military Aircraft, Origins to 1918: An Illustrated History of Their Impact, Justin D. Murphy, page 2

- ^ China Reconstructs. China Reconstructs. 15 December 1984 [15 December 2021] –透過Google Books.

- ^ History of Science in Korea, Sang-un Chŏn, page 181

- ^ Kites- The History Attached With It. Sporteology. 2017-12-03 [2019-02-01] (美國英語).

- ^ Taking Flight: Inventing the Aerial Age, from Antiquity Through the First World War, Richard Hallion, pages 9-10

- ^ 신호연신호 개요 (Summary of sending a signal with a kite). Korea Culture & Contents Agency. [July 30, 2009]. (原始內容存檔於July 8, 2011) (韓語).

- ^ M. Robinson. Kites On The Winds of War. Members.bellatlantic.net. [2012-10-03]. (原始內容存檔於2012-01-21).

- ^ Saul, Trevor. Henry C Sauls Barrage Kite. Soul Search. August 2004 [2012-10-03]. (原始內容存檔於2013-05-23).

- ^ Grahame, Arthur. Target Kite Imitates Plane's Flight. Popular Science. May 1945 [2012-10-03].

- ^ World Kite Museum. World Kite Museum. [2012-10-03]. (原始內容存檔於2009-04-06).

- ^ Focke Achgelis Fa 330

- ^ Gazans Fly Firebombs Tied to Kites Into Israel, Sparking Several Blazes, Haaretz, 16 April 2018

- ^ Gazans use kites to set fire to fields, forests in Israel, JNS, 17 April 2018

- ^ Flaming kite from Gaza sets Israeli warehouse ablaze, Times of Israel, 21 April 2018

- ^ Continuing kite threat puts Israeli farmers on edge, YNET, 24 April 2018

- ^ Kite Terrorism: Compensation to Victims 網際網路檔案館的存檔,存檔日期2018-05-02., Hadashot, 2 May 2018

- ^ Ronalds, B.F. Sir Francis Ronalds: Father of the Electric Telegraph. London: Imperial College Press. 2016. ISBN 978-1-78326-917-4.

- ^ Wales launches £25m underwater kite-turbine scheme The Guardian (retrieved 17 November 2015)

- ^ Underwater Kites Can Harness Ocean Currents to Create Clean Energy Smithsonian.com (retrieved 17 November 2015)

- ^ Kite Museums – Drachen Foundation. Drachen.org. [2018-04-29]. (原始內容存檔於2018-04-30).

- ^ Kite.(2007) Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Britannica.com. [2013-04-22].

- ^ Basant: Colorless skies as ban on kite flying in Pakistan continues. www.aa.com.tr. [2022-03-14].

- ^ Pogadaev, Victor. Svetly Mesyatz-Zmei Kruzhitsa (My Lord Moon Kite) - "Vostochnaya Kollektsia" (Oriental Collection). M.: Russian State Library. N 4 (38), 2009, 129-134. ISSN 1681-7559

- ^ Sijapati, Alisha. Kite fight over Kathmandu. Nepalitimes.com. 8 October 2020 [2020-11-18] (美國英語).

- ^ Story of a Kite. The New Indian Express. [2018-03-15].

- ^ Weifang World Kite Museum in Weifang,Shandong Province - China.org.cn. China.org.cn. [2020-08-25].

- ^ Skeat, Walter William. Malay Magic: An Introduction to the Folklore and Popular Religion of the Malay Peninsula. Psychology Press. 1965: 485. ISBN 978-0-7146-2026-8.

- ^ 八日市大凧まつり 網際網路檔案館的存檔,存檔日期2015-05-26.NHK(video)

- ^ GIANT KITE FESTIVALS IN JAPAN 網際網路檔案館的存檔,存檔日期2012-03-11. Japanese Kite Collection

- ^ A spectacular festival of some 100 large kites flying over sand dunes. Japan National Tourism Organization

- ^ Hamamatsu Matsuri 網際網路檔案館的存檔,存檔日期2015-05-27. NHK

- ^ mirantesmt.com. (原始內容存檔於2015-08-27).

- ^ Moore, Brian L. (1995). Cultural Power, Resistance, and Pluralism: Colonial Guyana 1838-1900. McGill-Queen's Press - MQUP, ISBN 978-0-7735-1354-9

- ^ Brereton, Bridget; Yelvington, Kevin A. (1999). The Colonial Caribbean in Transition. University Press of Florida, ISBN 978-0-8130-1696-2

- ^ Welcome to guyanachronicle.com. [15 December 2021]. (原始內容存檔於2008-04-16).

- ^ Search Results. Guinness World Records. [15 December 2021].

- ^ Largest kite flown. Guinnessworldrecords.com. 15 February 2005.

- ^ Highest altitude by a single kite. Guinness World Records. 23 September 2014 [14 December 2021].

- ^ Moore, R. Untitled Page. Kitesite.com.au.

- ^ Egypt grounds kites for 'safety', 'national security'. news.yahoo.com. [July 12, 2020].

外部連結[編輯]

- The earliest depiction of kite flying in European literature in a panorama of Ternate (Moluccas) 1600.

- Mathematics and aeronautical principles of kites.

- Kitecraft and Kite Tournaments (1914)—A free public domain e-book

- Trivedi, Parthsarathi; et al. Aerodynamics of Kites (PDF). [8 February 2013]. (原始內容 (PDF)存檔於12 June 2013).

- Eyes on Brazil

Template:Application of wind energy Template:Aircraft types (by method of thrust and lift)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||