歐洲航天局科學計劃

歐洲太空總署的科學計劃(Science Programme)[1][2][a]是一項長期的空間科學和太空探索任務規劃,由該機構科學理事會管理,通過制定各十年期航天計劃,資助歐洲航天機構和其它組織所開發、發射和運營的任務。首期「地平線 2000」計劃在1985年至1995年間推動了包括四項「奠基石任務」—太陽和太陽圈探測器及星簇2號衛星、X射線多鏡面牛頓衛星、羅塞塔號和赫歇爾空間天文台等在內的八項任務的開發;第二期「地平線 2000+」計劃,在1995年至2005年期間促進了「蓋亞任務、雷射干涉空間天線開路者號和貝皮可倫坡號的開發;當前的第三期「宇宙願景」計劃,自2005 年來,已資助了十項任務的開發,其中包括三項旗艦任務:木星冰月探測器、先進高能天體物理學望遠鏡和雷射干涉空間天線。目前正在規劃即將推出的第四期「遠航 2050」計劃。另外 ,在科學計劃中,還有與歐洲以外航天機構和組織的合作,如與美國宇航局的「卡西尼-惠更斯號」和中國國家航天局的微笑計劃項目。

管理[編輯]

| 歐空局科學計劃諮詢結構[8][9][10] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

科學計劃由歐洲太空總署 (ESA) 科學理事會管理[11],其目標包括提升歐洲在太空科學領域的地位、促進技術創新以及維護歐洲太空基礎設施,如發射服務和太空飛行器運營[11],為歐空局強制性計劃之一,所有歐空局成員國都必須參與[12][13],並按照國民生產淨值的比例繳納一定的會費,以確保該計劃及其任務的長期財務安全[14]。該計劃的制訂過程採用「自下而上」的結構,歐洲科學界可通過諮詢機構引導計劃的方向[7][15]。這些機構向總幹事和科學部主任提出有關該計劃的建議[16][17],並可將建議獨立報告給歐空局的科學計劃委員會(SPC)—整個計劃的管理機構[16][18]。該計劃目前的諮詢結構由天文學工作組 (AWG) 和太陽系與探索工作組 (SSEWG) 組成[8][9],他們向高級空間科學諮詢委員會 (SSAC) 報告,該委員會則向該機構的董事會報告[17]。諮詢機構的成員資格為期三年[19],天文學工作組和太陽系與探索工作組的主席也是高級空間科學諮詢委員會的成員[8][9][19]。另外,還可設立特設諮詢小組,就某些任務提案或規劃周期的制定提供諮詢意見[10]。

該計劃中的任務是從歐洲科學界成員向歐空局提交的提案中競選評出[20],在每次競選中,歐空局都會概述提案需要滿足的各類任務評審標準[21],它們分別是「L」級大型任務、「M」級中型任務、「S」級小型任務和「F」級快速任務,每類任務都有不同的預算上限和實施時間表[5][21]。參選提案隨後由天文學工作組、太陽系與探索工作組、歐空局工程師和所有相關的特設工作組進行審查,作為「第 0 階段」可行性研究的一部分[22][23]。對需要開發新技術的任務,會在研發期間由歐洲空間研究與技術中心的並行測試部門進行審查[24]。研究結束後,在「A 階段」最多選出三項入圍提案,並為每項候選任務制定初步設計[23][25]。然後,科學計劃委員會就哪項提案進入「B」到「F」階段作出最終決定,包括任務中所用太空飛行器的開發、建造、發射和處置[26][27][28]。在 A 階段,每項候選任務會分配兩個相互競爭的承建商來建造太空飛行器,並在 B 階段選擇獲選任務的承建商[25][27]。

歷史[編輯]

背景[編輯]

歐洲太空總署成立於1975年5月,由歐洲空間研究組織(ESRO)和歐洲發射裝置發展組織(ELDO)合併而成[29][30][31]。1970年,歐洲空間研究組織的發射計劃管理諮詢委員會 (LPAC) 決定不執行當時認為超出該組織預算和能力的天文學或行星探測任務[32][33],這意味著所有大型科學任務必須要與其他政府航天機構和組織進行合作[33]。1980年,這一政策得到有效改變,時任歐空局科學部主任恩斯特·特倫德倫伯格(Ernst Trendelenburg)和新成立的決策機構—科學計劃委員會 (SPC) 決定選擇發射飛越哈雷彗星的「喬托號」偵測任務和「依巴谷」天體測量任務[34][35],加上1983年3月選定的國際紫外線探測天文台[35],成為三項首次用阿麗亞娜空間運載火箭發射的歐洲探索任務,自此使歐洲擁有了自主的發射服務[36][37]。除此之外 ,缺乏長期科學任務計劃,以及美國宇航局在國際合作的太陽極地任務(後命名為「尤利西斯號」)預算挫折[38],刺激了長期科學計劃的發展。通過該計劃,歐空局可在更長時間內獨立於其他機構和組織持續地規劃任務[38][39]。歐空局科學理事會的決策和諮詢結構在該計劃成立之前就立即發生了改革。20世紀70年代,歐空局科學諮詢委員會(SAC)接替了發射計劃管理諮詢委員會 (LPAC),就所有科學問題向總幹事提供諮詢,天文工作組(AWG)和太陽系工作組(SSWG)也直接向總幹事報告[40]。20世紀80年代初,歐空局科學諮詢委員會(SAC)被空間科學諮詢委員會 (SSAC) 取代,後者的任務是向科學部主任報告天文學工作組和太陽系工作組的發展情況[41]。此外,前歐空局科學諮詢委員會主席羅傑-莫里斯·博內特(Roger-Maurice Bonnet)於1983年5月接替特倫德倫伯格擔任科學部主任[42]。

地平線 2000[編輯]

闡述[編輯]

1983年11月和12月,歐空局根據博內特於1983年底向科學計劃委員會提交的社會驅動計劃的構想,首次向歐洲科學界公開徵集任務提案[44][45][46]。這次徵集共產生了68項提案,其中30項屬於天文學領域,34項為太陽物理學領域,還有4項其它領域的概念[46][47][48]。並從空間科學諮詢委員會、歐洲核子研究中心、歐洲科學基金會、歐洲南方天文台和國際天文學聯合會等機構召集相關成員[49],組建了一個由時任荷蘭空間研究所主管約翰·布雷克(Johan-Bulek)領導的臨時「調查委員會」[50][51],專門審查提交的提案[10][52]。在整個1984年初,調查委員會為一系列任務制定了計劃,這些任務劃分為三類—實施時間較長,需要兩年預算的「奠基石」級任務;需一個年度預算的中型任務和只花費半年度預算的小型任務[53][54]。1984年,科學計劃的預算為每年1.3億歐洲貨幣單位,並建議在1991年之前每年增加7%,屆時預算將固定為每年2億歐洲貨幣單位[55]。中型和小型類項目稍後將合併為一個中型類項目,代表花費一半預算的任務[56]。這一類別在內部被稱為「藍色任務」,以它們在公開計劃圖表中被藍框表示而命名[56]。該計劃最初三項奠基石項目都各自針對某一特定的科學領域,參選提案需致力於填補這一領域[54],而中型任務的目標則有待於與任務提案一起進行競選[56][57][58]。選定的奠基石項目是彗星採樣返回任務、X射線光譜學任務和亞毫米天文學任務[59][60][61]。因財務和技術不足而未選定的基礎目標,但調查委員會稱具有地平線 2000 計劃外機會的項目有太陽探測器、火星探測車和二維干涉測量任務[62]。

1984年6月,調查委員會在威尼斯聖喬治·馬焦雷島召開了最後一次會議,會上向時任歐空局總幹事埃里克·奎斯特加德(Erik Quistgaard)和歐洲科學界主要成員提交了「地平線2000」計劃[54][63][64]。該計劃的廣義目標是擴大科學知識,將歐洲建立為空間科學的發展中心,為歐洲科學界提供機會,並促進太空技術產業的創新[65]。會議通過了太陽系工作組提出的第四號奠基石項目—日地科學計劃(STSP),該計劃由太陽和日光層觀測站和星團衛星提案組成,成為地平線2000計劃下首批選中發射的任務[66][67]。1985年,奎斯特加德在羅馬舉行的部長理事會上提出了地平線2000計劃並獲得批准。到1989年,預算每年只增加5%,而不是要求到1991年達到的7%[64][68][69],這隻夠為地平線2000目標提供約一半的資金[69]。但1990年海牙部長理事會批准將5%的年增長率延長至1994年,這使得所有地平線2000任務都能獲得全額資金[70][71][72]。

實施 [編輯]

1985年6月,歐空局在靈比舉辦的一次研究會上,X射線多鏡面任務(XMM)被列為X射線光譜學奠基石任務,該任務是一台由12架低能望遠鏡和7架高能望遠鏡組成的空間天文台[73]。但受客觀條件限制,到1987年,任務有效載荷整體削減至7台望遠鏡[74]。雖然歐洲X射線天文台衛星(EXOSAT)的成功啟發了任務規劃者通過將太空飛行器發射到高偏心軌道來提高任務觀測效率[75][76],可使太空飛行器的有效載荷減少到最終設計的三架大型望遠鏡—每架望遠鏡的反射面積為1500厘米2[75][77]。到1986年,預計第四號奠基石項目—日地科學計劃的成本將超出所分配的4億歐洲貨幣單位預算[78][79]。在1986年2月的一次會議上,科學計劃委員會被告知有可能取消該奠基石項目,以便轉為在太陽和日光層天文台、星簇衛星和克卜勒火星軌道器提案中選擇一項中型任務[78][80],這在空間科學諮詢委員會成員中得到了普遍的支持[81]。而一個月前發生的挑戰者號太空梭災難對該計劃產生了極大的負面影響,因為太陽和日光層天文台原計劃搭載在太空梭上發射升空[82]。儘管如此,通過簡化太陽和日光層天文台,以及將星團衛星減少為三顆[83][84],太陽系工作組、空間科學諮詢委員會和科學計劃委員會還是堅持了對日地科學計劃項目的承諾。1986年10月與美國宇航局達成的一項合作協議,進一步降低了任務的成本—美國宇航局將提供測試、發射服務和衛星操作,並提供各類科學儀器[85][86],同時取消自已的赤道任務,轉而使用搭載了美國探測儀器的第四顆星簇衛星[87][b]。

第一次中級飛行任務是1982年歐空局在地平線2000計劃前,從提交的提案中選出的[89],一艘由一組美國和歐洲科學家提出的搭載在美國卡西尼號太空飛行器上的土衛六探測器[89],並與美國-歐洲聯合的萊曼紫外線天文學衛星和魁煞甚長基線干涉天文台一起成為最終入圍者[90][91][92]。歐洲-蘇聯聯合的維斯塔小行星多次飛越任務和格拉斯普伽馬射線天文台也參加了評選[93][94],但被天文學工作組和太陽系工作組拒絕[92][95]。挑戰者號失事導致的預算削減迫使美國宇航局撤消了對萊曼和魁煞項目的支持[96]。1988年11月,科學計劃委員會選擇了土衛六探測器[97],根據會上瑞士天文學家的建議,該探測器更名為惠更斯號,以紀念在1655年發現了土衛六的克里斯蒂安·惠更斯[92]。

在1989年6月的第二次中級任務競選中,美國和歐洲機構聯合提出了國際伽瑪射線天體物理實驗室,一台結合了格拉斯普與美國核天體物理探測器(NAE)功能的伽馬射線天文台[98]。美國核天體物理探測器在當年美國宇航局探索者計劃評選中落敗[99],但美國宇航局支持這一提案,俄羅斯科學院後來曾提出用質子運載火箭發射它,以換取對該探測器的觀測時間[100][101]。儘管很擔心美國宇航局對該任務的承諾及資金來源,但在1993年6月,科學計劃委員會還是選擇了國際伽瑪射線天體物理實驗室項目[102],並由美國宇航局提供深空網絡服務和一台光譜儀[103][104]。作為回應,美國宇航局不通過競選,直接將國際伽瑪射線天體物理實驗室項目列為探索者計劃任務[105]。對於這一點,加上對為此次任務所設計光譜儀靈敏度的擔憂,在美國宇航局的諮詢機構中引起了爭議[105][106]。1994年9月,歐空局和美國航天局以缺乏財政支持為由,決定終止美國航天局在光譜儀方面的合作[107],法國國家太空研究中心迅速承擔了財政負擔,並主導了新光譜儀的設計和製造[108]。

1993年11月,羅塞塔號和「福斯特號」入選為第三和第四次奠基石任務[109],後一任務最終被重命名為赫歇爾空間天文台。1996年7月,宇宙背景輻射各向異性衛星和背景各向異性測量(COBRAS/SAMBA)後改名為普朗克衛星,被選為第三次中型任務[110][111]。截至2016年12月,地平線2000任務中尚有四項(包括三項奠基石任務和一個中型任務)仍在運行。

地平線 2000+[編輯]

「地平線2000+」是地平線2000計劃的延續,為上世紀90年代中期制定的1995年至2015年期間執行的任務計劃[112]。它包括了另外兩項奠基石級任務,即2013年發射的星際測繪任務蓋亞號和2018年發射的貝皮可倫坡號水星探測任務,以及將於2015年發射,以測試未來雷射干涉空間天線(莉莎號)的技術演示衛星雷射干涉空間天線開路者號,

「地平線2000」和「地平線2000+」計劃下的所有任務都取得了成功,只有1996年發射的星簇衛星因火箭爆炸而被毀,但在2000年成功建造並發射了替代的星簇2號衛星。

宇宙願景[編輯]

宇宙願景2015-2025是歐空局空間科學任務規劃的當前長期計劃,最初的構想和概念徵集發起於2004年,隨後在巴黎舉辦了一次研討會,探討在天文學和天體物理學、太陽系探索和基礎物理學等更廣泛領域內更全面地定義宇宙願景的主題。到2006年初,圍繞以下4項關鍵問題制定了10年計劃:

2007年3月,正式發布了任務構想徵集,共收到19項天體物理學、12項基礎物理學和19項太陽系任務建議。

大型[編輯]

大型(L級)飛行任務最初打算與其他合作夥伴聯合實施,歐空局設定的費用不超過9億歐元。然而,在2011年4月,很明顯,美國的預算壓力意味著在第一項大型任務上不太可能與美國宇航局取得合作。因此,接下來的選擇被迫推遲,任務範圍重新確定為由歐空局主導,國際參與有限[113]。宇宙願景計劃共選擇了三項大型任務,分別為:計劃於2023年發射的木星和木衛三軌道飛行器「果汁號」[114];2034年發射X射線天文台「雅典娜號」[115]以及 2037年發射的太空引力波觀測台「莉莎號」[116]。

中型[編輯]

中級(M級)任務是相對獨立的項目,成本上限約為5億歐元。前兩項中級任務:近距離太陽觀測的太陽物理學軌道飛行器任務[117]和旨在研究暗能量及暗物質的「歐幾里德」可見光-近紅外太空望遠鏡任務[118]於2011年10月選出[119]。2014年2月19日,尋找系外行星並測量恆星振盪的「柏拉圖號」[120]一舉擊敗回聲號(EChO)、閣樓號(LOFT)、馬可波羅-R(MarcoPolo-R)和時空探索者與量子等效原理空間測試(STE-QUEST)等空間探測計劃,成為第三項中級任務[121]。2015年3月,在對第四次中級飛行任務提案作初步篩選後,6月4日公布了三項入選進一步研究的候選任務名單[122][123][124]:雷神號電漿體天文台、西佩號X射線天文台和系外行星大氣紅外遙感大調查衛星愛麗兒號。最終,通過觀測附近系外行星凌日來確定其化學成分和物理條件的愛麗兒號空間天文台[124],在2018年3月20日被宣布中選第四項中級任務[125][126]。第五項中級任務角逐於2021年6月結束,獲勝的展望號金星軌道器將在2031發射升空[127]。斯皮卡號遠紅外天文台和忒修斯號伽馬射線望遠鏡是此次參選中的另外兩項提案[128]。

小型[編輯]

歐空局的小型飛行任務(S級)預算不超過5000萬歐元,2012年3月發布了第一次任務提案徵集公告,獲選的提案需要在2017年前完成發射準備[129],此次征告收到約70份意向書[130]。基奧普斯號是一項通過光度測量搜索系外行星的任務,2012年10月被選為第一項S級任務,將於2019年秋季發射[131][132];2015年6月,歐空局與中國科學院聯合開展的地球磁層圈和太陽風交互作用研究項目—微笑任務,從13項競選提案中脫穎而出, 成為第二項S級任務[133],截至2021年4月,微笑計劃將定於2024年11月發射[134]。

快速型[編輯]

在2018年5月16日的歐空局科學計劃委員會 (SPC) 研討會上,提出了創建一系列特殊機會的快速級(F 級)任務。 從第四號中級任務開始,這些快速級任務將與每次的中級任務一起聯合發射,並將側重於「創新實施」,以擴大任務涵蓋的科學主題範圍。但將快速級任務納入宇宙願景計劃需要增加科學預算[135]。快速級任務從選擇到發射必須在十年時間之內,且重量不超過1000公斤[136]。2019年6月,選出了首個快速級任務-彗星攔截器[137][138]。

機會任務[編輯]

有時,歐空局會資助其它航天機構主持的太空任務。機會任務能讓歐空局科學界以相對較低的成本參與合作夥伴主導的任務,設定的成本上限為5000萬歐元[139]。歐空局的機會任務包括對日出號、虹膜號、顯微鏡號、普羅巴3號、X射線成像和光譜學任務(XRISM)、火星太空生物、愛因斯坦探針衛星和火星衛星探測器的資助[139]。對日本宇宙航空研究開發機構的斯皮卡號(宇宙和天體物理學太空紅外望遠鏡)任務的資助雖被評估為宇宙願景中的機會任務,但它不再在該框架內考慮[140],現已被列為第五號中級任務提案之一。

遠航2050[編輯]

歐空局科學計劃的下一個十年期規劃是「遠航2050」,它將涵蓋2035年至2050年的空間科學任務。該計劃起始於2018年12月任命的高級委員會和2019年3月發表的白皮書公告。[141]。

該計劃目前預計有三項大型任務和六到七項中型任務,以及小型和機遇任務[142]。2021年6月11日,高級委員會發布了遠航2050計劃,並為接下來的三大任務推薦了以下科學主題[143]:

- 巨行星的衛星—探測擁有海洋的氣體巨行星衛星的任務。

- 從溫和的系外行星到銀河系—描述系外行星特徵或調查銀河系形成歷史的任務。

- 早期宇宙的新物理探測器—通過宇宙微波背景、引力波或其他基本天體物理現象來研究早期宇宙的任務。

任務[編輯]

地平線2000

- 奠基石 1 – 太陽和日光層觀測站,1995年12月發射,運行中 – 歐空局-美國宇航局為空間天氣預報提供實時數據的聯合太陽觀測任務。

- 奠基石 1 – 星簇衛星,1996年6月發射,失敗 – 使用四顆相同衛星研究行星磁層的地球觀測任務,發射失敗。

- 重新發射– 星簇2號衛星,2000年7月和8月發射,運行中 – 成功完成任務接替。

- 奠基石 2 – X射線多鏡面任務,1999年12月發射,運行中 –一架研究宇宙中所有範圍X射線源的X射線空間望遠鏡。

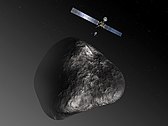

- 奠基石 3 – 羅塞塔號,2004年3月發射,已完成 – 丘留莫夫-格拉西緬科彗星軌道器任務,研究彗星及其演化。

- 奠基石 4 – 赫歇爾空間天文台,2009年5月發射,已完成 –通用天文學紅外太空觀測任務。

- 中1號 – 惠更斯號,1997年10月發射,已完成 – 「卡西尼-惠更斯號」任務的土衛六著陸器組件,首次登陸外太陽系星球。

- 中2號 – 國際伽瑪射線天體物理實驗室,2002年10月發射,運行中 – 伽馬射線空間天文台,也可觀測X射線和可見光波長。

- 中3號 – 普朗克衛星,2009年5月發射,已完成 – 繪製宇宙微波背景及其各向異性的宇宙學任務。

地平線 2000 +

- 第1次任務– 蓋亞號,2013年12月發射,運行中 – 天體測量任務,測量銀河系中超過十億個天體的位置及距離。

- 第2次任務– 雷射干涉空間天線開路者號,2015年12月發射,已完成 –演示宇宙願景莉莎號引力波觀測站技術的任務。

- 第3次任務– 貝皮可倫坡號,2018年10月發射,運行中 – 歐空局-日本宇宙航空研究開發機構聯合水星偵測任務,使用兩艘分別運行的獨特探測器。

宇宙願景

- 大1號 – 果汁號,2023年8月發射,2031年進入軌道。未來 – 木星軌道飛行器任務,重點研究四顆伽利略衛星木衛二、木衛三和木衛四。

- 大2號 – 雅典娜號,2034年發射,未來 – X射線空間觀測任務,用於接替「X射線多鏡面任務」望遠鏡。

- 大3號 – 莉莎號,2037年發射,未來 – 第一次專門的引力波太空觀測任務。

- 中1號 – 太陽軌道器,2020年發射,運行中 –太陽觀測任務,旨在在0.28天文單位的近日點對太陽進行遙感和原位研究。

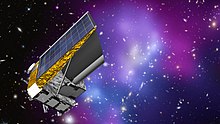

- 中2號 – 歐幾里得衛星,2023年初發射,未來 – 重點聚焦暗物質和暗能量的可見光和近紅外太空觀測任務。

- 中3號 – 柏拉圖號,2026年發射,未來 – 類似太空觀測任務的凌日系外行星巡天衛星,旨在發現和觀測系外行星。

- 中4號 – 愛麗兒號,2029年發射,未來 – 研究已知系外行星大氣層的紅外太空天文台任務。

- 中5號 – 展望號,2031年發射,未來 – 金星測繪軌道飛行器任務[127]。

- 小1號 – 太陽和日光層觀測站,2019年12月發射,運行中 –重點研究已知系外行星的空間望遠鏡任務。

- 小2號 – 微笑計劃,2024年11月發射,未來 –歐空局與中國科學院聯合執行的地球觀測任務,研究地球磁層與太陽風之間的交互作用。

- 快1號 – 彗星攔截器,2029年發射,未來。

時間表[編輯]

另請查看[編輯]

參考文獻[編輯]

注釋

- ^ Also known as the ESA Science Programme,[3] ESA's Science Programme,[4][5] or the ESA scientific programme.[6][7]

- ^ Equator was a planned mission by NASA to explore Earth's magnetosphere from an equatorial orbit. It was NASA's contribution to a joint mission with the STSP known as the International Solar-Terrestrial Physics (ISTP) programme.[87][88]

資料來源

- Bonnet, Roger-Maurice; Bleeker, Johan; Olthof, Henk. Longdon, Norman , 編. Space Science – Horizon 2000. Esa's Report to the ... Cospar Meeting (Noordwijk, Netherlands: ESA Scientific & Technical Publications Branch). 1984 [9 July 2019]. ISSN 0379-6566. (原始內容存檔於9 July 2019).

- Bonnet, Roger-Maurice. Fundamental science and space science within the Horizon 2000 programme. Rolfe, Erica (編). A Decade of UV astronomy with the IUE satellite: proceedings of a celebratory symposium held at Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Maryland, USA, 12-15 April 1988, Volume 2. Noordwijk, Netherlands: ESA Publications Division. 1988: 85–94 [15 July 2019]. Bibcode:1988ESASP.281b..85B. ISSN 0379-6566. (原始內容存檔於15 July 2019).

|journal=被忽略 (幫助)

- Bonnet, Roger-Maurice. European Space Science - In Retrospect and in Prospect. Battrick, Bruce; Guyenne, Duc; Mattok, Clare (編). ESA Bulletin No. 81. Noordwijk, Netherlands: ESA Publications Division. 1995: 6–17 [7 July 2019]. ISSN 0376-4265. (原始內容存檔於2021-06-04).

|journal=被忽略 (幫助) - Bonnet, Roger-Maurice. Cassini–Huygens in the European Context. Fletcher, Karen (編). Titan: From Discovery to Encounter: Proceedings of the International Conference, 13-17 April 2004, ESTEC, Noordwijk, the Netherlands. Noordwijk, Netherlands: ESA Publications Division. 2004: 201–209 [7 July 2019]. Bibcode:2004ESASP1278..201B. ISBN 9789290929970. (原始內容存檔於7 July 2019).

- Cogen, Marc. An Introduction to European Intergovernmental Organizations 2nd. Abingdon, England: Routledge. 2016 [8 July 2019]. ISBN 9781317181811. (原始內容存檔於2021-12-29).

- European Science Foundation; National Research Council. U.S.-European Collaboration in Space Science. Washington, D.C., United States: National Academies Press. 1998 [6 July 2019]. ISBN 9780309059848. (原始內容存檔於2021-12-29).

- European Space Agency. The Science Programme. The ESA Programmes (BR-114). 1995 [6 July 2019]. (原始內容存檔於6 July 2019).

- European Space Agency. How a Mission is Chosen. ESA Science. 2013 [7 July 2019]. (原始內容存檔於7 July 2019).

- European Space Agency. Science Programme. ESA Industry Portal. 2015 [6 July 2019]. (原始內容存檔於6 July 2019).

- Harvey, Brian. Europe's Space Programme: To Ariane and Beyond. Dublin, Ireland: Springer Science+Business Media. 2003 [9 July 2019]. ISBN 9781852337223. (原始內容存檔於2021-05-08).

- Jansen, Fred; Lumb, David; Schartel, Norbert. X-ray Multi-mirror Mission (XMM-Newton) observatory. Optical Engineering. 3 February 2012, 51 (1): 011009–011009–11. Bibcode:2012OptEn..51a1009L. S2CID 119237088. arXiv:1202.1651

. doi:10.1117/1.OE.51.1.011009.

. doi:10.1117/1.OE.51.1.011009.

- Krige, John; Russo, Arturo; Sebesta, Laurenza. Harris, R. A. , 編. A History of the European Space Agency, 1958 – 1987 (Vol. II - The Story of ESA, 1973 to 1987) (PDF). Noordwijk, Netherlands: ESA Publications Division. 2000 [8 July 2019]. ISBN 9789290925361. (原始內容存檔 (PDF)於8 July 2019).

- Wilson, Andrew. ESA Achievements (PDF) 3rd. Noordwijk, Netherlands: ESA Publications Division. 2005 [10 July 2019]. ISBN 9290924934. (原始內容存檔 (PDF)於10 July 2019).

引文

- ^ ESA science programme planning cycles. ESA Science. 4 March 2019 [7 July 2019]. (原始內容存檔於7 July 2019).

The Science Programme of the European Space Agency (ESA) relies on long-term planning of its scientific priorities.

- ^ ESA 2015,"The Science Programme within the Directorate of Science has two main objectives [...] The Science Programme has a long and successful history..."

- ^ ESA Media Relations Office. ESA Science Programme's new small satellite will study super-Earths. European Space Agency. 12 October 2012 [6 July 2019]. (原始內容存檔於6 July 2019).

Studying planets around other stars will be the focus of the new small Science Programme mission, Cheops, ESA announced today. [...] The mission was selected from 26 proposals submitted in response to the Call for Small Missions in March [...] Possible future small missions in the Science Programme should be low cost and rapidly developed, in order to offer greater flexibility in response to new ideas from the scientific community.

- ^ ESA 1995,"ESA's Science Programme has three primary features that single it out among the Agency's activities [...] ESA's Science Programme has consistently focussed on missions with a strong innovative content."

- ^ 5.0 5.1 Call for a Fast (F) mission opportunity in ESA's Science Programme. ESA Science. 16 July 2018 [7 July 2019]. (原始內容存檔於7 July 2019).

This Call for a Fast mission aims at defining a mission of modest size (wet mass less than 1000 kg) to be launched towards the Earth-Sun L2 Lagrange point as a co-passenger to the ARIEL M mission, or possibly the PLATO M mission.

- ^ ESA 2013,"The ESA scientific programme is based on a continuous flow of projects that fulfil its scientific goals."

- ^ 7.0 7.1 ESF and NRC 1998,page 36, "The fundamental rule of ESRO, and subsequently ESA, has been that ESA exists to serve scientists and that its science policy must be driven by the scientific community, not vice versa [...] [This] explains the determining influence that ESA's advisory structure has on the definition and evolution of the scientific program."

- ^ 8.0 8.1 8.2 European Space Agency. Astronomy Working Group. ESA Cosmos Portal. 2011 [6 July 2019]. (原始內容存檔於6 July 2019).

The Astronomy Working Group (AWG) provides scientific advice mainly to the Space Science Advisory Committee (SSAC). [...] The chair of the working group is also a member of the SSAC.

- ^ 9.0 9.1 9.2 European Space Agency. Solar System and Exploration Working Group (SSEWG). ESA Cosmos Portal. 2011 [6 July 2019]. (原始內容存檔於6 July 2019).

The Solar System and Exploration Working Group (SSEWG) provide scientific advice mainly to the Space Science Advisory Committee (SSAC). [...] The chair of the working group is also a member of the SSAC.

- ^ 10.0 10.1 10.2 ESF and NRC 1998,page 36, "還可任命其他臨時工作組就特定主題提供諮詢意見. [...] 另一個是所謂的調查委員會,該委員會根據歐洲科學共同體提供的投入制定了空間科學長期計劃(即地平線2000計劃)。"

- ^ 11.0 11.1 ESA 2015,"The Science Programme within the Directorate of Science has two main objectives; To provide the scientific community with the best tools possible to maintain Europe's competence in space; To contribute to the sustainability of European space capabilities and associated infrastructures by fostering technological innovation in industry and science communities, and maintaining launch services and spacecraft operations."

- ^ Cogen 2016,page 221, "All member states must participate in the mandatory programmes [...] Today, ESA's mandatory programmes are carried out under the General Budget, the Technology Research Programme, the Science Programme and ESA's technical and operational infrastructure."

- ^ ESA 1995,"...it is the only mandatory programme [...] In 1975, when ESRO and ELDO were merged to form ESA, it was immediately decided that the Agency's Science Programme should be mandatory."

- ^ ESA 2015,"All Member States contribute pro-rata to their Net National Product (NNP) providing budget stability and allowing long-term planning of its scientific goals. For this reason, the Science Programme is called 'mandatory'.

- ^ ESA 2015,"Long-term science planning and mission calls are established through bottom-up processes. This relies on broad participation, with input and peer reviews of the space science community. The ESA Science Programme is foremost science-driven."

- ^ 16.0 16.1 ESF and NRC 1998,page 36, "They advise the director general and the director of the scientific program on all scientific matters, and their recommendations are independently reported to the SPC."

- ^ 17.0 17.1 European Space Agency. Space Science Advisory Committee (SSAC). ESA Cosmos Portal. 2011 [6 July 2019]. (原始內容存檔於6 July 2019).

The Space Science Advisory Committee (SSAC) is the senior advisory body to the Director of Science (D/SCI) on all matters concerning space science included in the mandatory science programme of ESA.

- ^ Cogen 2016,page 219, "The Council is responsible for the establishment of a Science Programme Committee which deals with any matter relating to the mandatory scientific programme."

- ^ 19.0 19.1 ESF and NRC 1998,page 36, "Membership on the advisory bodies is for 3 years, and the chairs of the AWG and SSWG are de jure members of the SSAC."

- ^ ESA 2013,"These projects are identified and selected using the mechanism of the open call. Whenever appropriate, and compatible with the programme goals and constraints, ESA issues a call for proposals for new science missions."

- ^ 21.0 21.1 ESA 2013,"The call includes descriptions of the scientific goals, size, cost of the mission, together with programmatic and implementation details. [...] Missions fall into three categories: small (S-class), medium (M-class) and large (L-class), their size reflecting the scientific goals addressed and eventually the cost and development time required."

- ^ ESA 2013,"ESA's various scientific advisory committees of experts assess the submissions. [...] ESA’s engineers also make an initial assessment of the feasibility of the missions. [...] Phase 0; Mission analysis and identification..."

- ^ 23.0 23.1 Bonnet 2004,page 203, "Following a normal cycle of selection, through the Working Group, ESA undertook a feasibility study in 1984-1985, followed by the selection for Phase A in 1986."

- ^ ESA 2013,"This identifies any new technology that will need to be developed to make the mission possible. The majority of these studies are conducted internally at ESA's Concurrent Design Facility (CDF)."

- ^ 25.0 25.1 ESA 2013,"The committees then make recommendations about which missions should proceed to 'Phase A'. [...] Usually two or three missions are downselected for the phase A study, for which two competitive industrial contracts are placed for each mission. Phase A results in a preliminary design for the mission."

- ^ ESA 2013,"Phase B; Preliminary Definition; Phase C; Detailed Definition; Phase D; Qualification and Production; Phase E; Utilisation; Phase F; Disposal..."

- ^ 27.0 27.1 ESA 2013,"Results are presented, again in Paris to the various committees, and a final decision on which proposal will be selected for each mission is made. [...] They will eventually lead to the 'adoption' of the mission and to the selection of one of the two industrial contractors to become the responsible for the whole implementation phase..."

- ^ Bonnet 2004,page 203–204, "The Titan Probe was eventually selected by ESA's SCP in Nov. 1988 as the first 'blue' mission of Horizon 2000, against four other missions: VESTA, LYMAN, QUASAT, and GRASP."

- ^ Krige et al. 2000,page 34, "The Convention establishing the European Space Agency was signed by ten European states on 30 May 1975 [...] At the same time the Conference of Plenipotentiaries adopted a Final Act including ten resolutions. These made allowance for the transition from ESRO and ELDO to ESA..."

- ^ Cogen 2016,page 217, "ESA is created in its current form in 1975, merging ELDO with ESRO, by the Convention for the Establishment of a European Space Agency of 30 May 1975."

- ^ Parks, Clinton. May 31, 1975: European Space Unites Under the ESA Banner. SpaceNews. 27 May 2008 [8 July 2019].

Established May 31, 1975, ESA formed from the merger of the European Space Research Organisation (ESRO) and the European Launcher Development Organisation (ELDO).

- ^ Krige et al. 2000,page 40, "Astronomy had suffered heavily in ESRO and had been explicitly demoted in priority by the LPAC in 1970."

- ^ 33.0 33.1 Bonnet 2004,page 201, "At their long term planning meeting in 1970, the LPAC decided not to plan any planetary missions because they were considered at the time too expensive and beyond the financial capabilities of ESRO. Cooperation with NASA or the USSR was the only option for Europe to participate in the exploration of the Solar System."

- ^ Bonnet 2004,page 201–202, "The first change from that policy was the proposal of the ESA Science Director, Ernst Trendelenburg, followed by the positive decision of ESA's SPC in 1980, to launch a fast fly-by mission to Halley's comet on the occasion of its return to the vicinity of the Sun in March 1986."

- ^ 35.0 35.1 Bonnet 1995,page 9, "These two events together explain the series of decisions taken between 1980 and 1983. Giotto and Hipparcos were selected by the SPC in 1980 (again with great difficulties in deciding between astronomy and solar-system missions) and ISO in March 1983."

- ^ Bonnet 1995,page 9, "The crisis came in the same period as the arrival of Ariane, which was successfully launched for the first time on Christmas Eve 1979, giving Europe full autonomy in accessing space. [...] All three missions were to use the Ariane launcher and were originally European-only missions."

- ^ Bonnet 2004,page 202, "Giotto (the name given to that mission) was the first purely European mission to explore the Solar System with its own launcher: Ariane 1, launched on July 2 1985."

- ^ 38.0 38.1 Bonnet 1995,page 9, "The ISPM crisis then opened their eyes as they realised for the first time the fragility of agreements signed by their trans- Atlantic counterparts. The Memorandum of Understanding, the official document establishing the basis for the cooperation, which had a binding significance on the European side, had a different interpretation for the Americans, with NASA's budget submitted to yearly discussion at the White House and in Congress."

- ^ Bonnet 1995,page 10, "In 1983, it became clear that ESA could no longer continue with its existing method of selecting project after project, without a long-term perspective and some kind of commitment that would allow the scientific community to prepare itself better for the future. ESA too needed a long-term programme in space science."

- ^ Krige et al. 2000,page 39, "The DG replaced the LPAC with the SAC (Science Advisory Committee) reporting directly to him on all scientific matters [...] A Life Sciences Working Group (LSWG) and Materials Sciences Working Group (MSWG) were also added to the AWG and SSWG, with all working groups reporting to the DG."

- ^ Krige et al. 2000,page 43, "The SAC, which had previously advised the Director General on all scientific matters, was now transformed into the SSAC (Space Science Advisory Committee). Its role became to advise the Director of Scientific Programmes on activities covered by the AWG and the SSWG."

- ^ Krige et al. 2000,page 43, "The spirited and controversial figure of Ernst Trendelenburg, who had spent almost twenty years in ESRO and then ESA, was replaced as Director of Scientific Programmes on 1 May 1983 by the French space scientist Roger Bonnet, former chairman of the SAC from 1978 to 1980."

- ^ Bleeker et al. 1984,page 3, "Over the past 25 years, space science has progressed from the pioneering and exploratory stage to a firmly established mature branch of fundamental science. The time has come to identify what the main thrusts of European space science should be for the coming decades to consolidate Europe's position in the forefront of scientific development"

- ^ Bleeker et al. 1984,page V, "The study, which led to the long term plan proposed in this document, was initiated by the Director of the Scientific Programme in September 1983 and was coordinated by a Survey Committee composed of scientists from different areas of fundamental science."

- ^ Krige et al. 2000,page 43, "Bonnet presented his idea to a meeting of the SPC in October 1983. The scientific community would be asked to suggest mission concepts which would be assessed by expert teams covering various disciplines in astronomy and the solar system sciences."

- ^ 46.0 46.1 Bonnet 1995,page 10, "Following a Call for Mission Concepts issued in Autumn 1983, to which the European scientific community responded with some 68 proposals (Table 2)..."

- ^ Krige et al. 2000,page 44, "The exercise produced 68 mission concepts, 33 in astronomy and 35 in solar system sciences."

- ^ Bonnet 1995,page 10, "Horizon 2000; 2/11 – 31/12/1983; Astronomy 30; Solar Physics 34; Miscellaneous proposals 4; Total no. proposals 68"

- ^ ESF and NRC 1998,page 36, "The SSAC formed the core of the survey committee. The membership of the survey committee, in addition to the SSAC [...] the European Science Foundation, Centre d'Études et de Recherches Nucléaires (CERN), the European Southern Observatory (ESO), and the International Astronomical Union (IAU)."

- ^ Harvey 2003,page 210, "The Agency adopted a team of scientists under Johan Bleeker and made a call for mission concepts: one that was widely supported (70 were received)..."

- ^ Bleeker et al. 1984,page V, "Johan Bleeker; Chairman of the Survey Committee"

- ^ Krige et al. 2000,page 43, "Their proposals would be evaluated by a Survey Committee which would draw up a global model programme for the years 1985 - 2004."

- ^ Krige et al. 2000,page 44, "The philosophy of Horizon 2000 was to divide projects into three classes: cornerstones, costing two annual budgets, and having long lead times; medium size projects, costing one annual budget, and of the class of then current missions like Giotto, Hipparcos and Ulysses; and low-cost projects, costing 0.5 annual budgets, typically participation in international programmes."

- ^ 54.0 54.1 54.2 Harvey 2003,page 210, "In the end, the committee produced a report called Space Science Horizon 2000, often referred to as Horizon 2000. This adopted the principle of 'cornerstone' missions, projects that will advance space science substantially in distinct areas over a period of many years."

- ^ Krige et al. 2000,page 44, "The overall budget for the programme was set at 200 MAU annually (1983 prices) as from 1991, this level to be achieved by an annual 7% increase over the 1984 budget (about 130 MAU)."

- ^ 56.0 56.1 56.2 Bonnet 2004,page 203, "In addition, Horizon 2000 offered the possibility of introducing at any stage in the selection process, medium-size or 'blue' missions, so-called because they were represented as blue boxes in the original diagram of the plan, whose cost would not be larger than half the value of the yearly budget."

- ^ Bleeker 1984,page 6, "Having established the major missions as the 'cornerstones' of the programme, provisions are to be made within the overall long term programme for a number of typical but as yet unidentified medium and small size missions [...] Detailed identification and selection of these smaller missions will be made at the appropriate time and follow the established competitive procedure."

- ^ Bonnet 1995,page 10, "In addition, the plan also included both small and medium size projects [...] but with no i priori (原文如此) exclusion of disciplines, so that a community not 'served' directly by the Cornerstones could still find a place in responding to the regularly released 'Calls for Ideas'."

- ^ Krige et al. 2000,page 44, "The astronomers selected an X-ray spectroscopy mission intended to build a third generation of observatory-class satellites for high-energy astrophysics. Their second cornerstone was in the field of submillimetre heterodyne spectroscopy [...] As for the solar system scientists, one of their cornerstones built on the achievements of Giotto, involving a mission to primordial bodies (comets and asteroids) with a return of pristine materials."

- ^ Bleeker et al. 1984,page 10–11, "The four cornerstones are: The Solar Terrestrial Programme (STP) [...] A Mission to Primordial Bodies including Return of Pristine Materials [...] A High Throughput X-Ray Mission for Spectroscopic Studies between 0.1- 20 keY [...] A High Throughput Heterodyne Spectroscopy Mission..."

- ^ Bonnet 1995,page 10, "so-called 'Cornerstones' were approved in four domains: solar-terrestrial physics (STSP), comet science (CNSR, now called Rosetta), X-ray (XMM), and submillimetre astronomy (FIRST)."

- ^ Bleeker et al. 1984,page 11, "As a follow-up to these four elements it is already possible to identify beyond the horizon 2004 other major thrusts: these are the Solar Probe and the Heliosynchronous Out of Ecliptic Mission in solar terrestrial physics, the Mars Rover in the planetary area, and, in astronomy, two-dimensional interferometry for high spatial resolution in the visible, infrared (IR) and millimetre (mm) wavelength region. These thrusts are beyond the present programme, for technological and financial reasons..."

- ^ Krige et al. 2000,page 44, "After the expert teams had prepared their reports an historic meeting of leading members of the European space science community on the San Giorgio Island in Venice from 30 May to 1 June 1984 consolidated the choices between them and produced a long-term plan which received the name Horizon 2000."

- ^ 64.0 64.1 Bonnet 1995,page 10, "...a survey committee and several Topical Teams were formed to [...] formulate recommendations to ESA's then Director General Erik Quistgaard, for him to present to the Council of Ministers in January 1985 in Rome."

- ^ ESA 1995,"The programme objectives are to: contribute to the advancement of fundamental scientific knowledge; establish Europe as a major participant in the worldwide development of space science; offer a balanced distribution of opportunities for frontline research to the European scientific community; provide major technological challenges for innovative industrial developments."

- ^ ESF and NRC 1998,page 52, "At the final meeting of the survey committee in May 1984 in Venice, Italy, only three cornerstones were originally foreseen. It was therefore a surprise when a fourth, consisting of the SOHO and Cluster missions, was introduced by the chairman of the Solar System Working Group. [...] This cornerstone was called the Solar-Terrestrial Science Program (STSP)..."

- ^ Krige et al. 2000,page 44, "The second, not foreseen in the original outline, sneaked in at the Venice meeting and covered the fields of solar and plasma physics. It involved combining two existing proposals, SOHO and Cluster."

- ^ Krige et al. 2000,page 44, "..as a result of which those present agreed to increase the level of the mandatory programme by 5% annually in real terms over the period 1985 - 1989."

- ^ 69.0 69.1 ESA 1995,"Carrying out Horizon 2000 required a special financial effort from the Member States, amounting to a progressive budgetary increase of 7% per year from 1985 to a steady state in 1992. The Council meeting at Ministerial Level in Rome authorised a slower progression of 5% a year until 1989, thus affording about 50% of the requested increase."

- ^ ESA 1995,"The realisation of the entire Horizon 2000 plan became dependent on such a progression of 5% a year being maintained until 1994. This progression was granted by the ESA Council in December 1990, thereby opening the way to full implementation of Horizon 2000."

- ^ Bonnet 1995,page 10, "...the ESA science budget was granted an annual increase of 5% above inflation [...] an increment that was to be implemented over ten years."

- ^ Krige et al. 2000,page 44, "This was subsequently extended at the Ministerial Meeting in The Hague to enable the programme to reach a level of almost 217 MAU in 1992 (in 1985 prices)."

- ^ Lumb et al. 2012,page 1, "...culminating in a mission presentation at an ESA workshop held in Lyngby, Denmark in June 1985. In the papers presented at this conference the mission design contained 12 low-energy and 7 high-energy telescopes..."

- ^ Lumb et al. 2012,page 1, "When the report of the telescope working group was delivered in 1987, the consideration of practical constraints had reduced the number of telescopes to a more modest total of 7."

- ^ 75.0 75.1 Lumb et al. 2012,pages 1, 4, "The mission was approved into implementation phase in 1994, and an improved observing efficiency achieved with a highly eccentric orbit allowed the number of telescopes to be reduced. [...] Effective area (1keV); 1500 cm2"

- ^ European Space Agency. XMM-Newton Overview. ESA Science. 4 June 2013 [9 July 2019]. (原始內容存檔於9 July 2019).

Following the experience with Exosat, which demonstrated the value of a highly eccentric orbit for long uninterrupted observations of X-ray sources, XMM was to be placed in a 48-hour period orbit using the Ariane 4 launcher.

- ^ Wilson 2005,page 206, "The heart of the mission is the X-ray telescope. It consists of three large mirror modules and associated focalplane instruments held together by the telescope's central tube"

- ^ 78.0 78.1 Krige et al. 2000,page 217, "To this, Bonnet replied that the Executive would offer the SPC the choice between implementing the STSP as a wholeor selecting one of the three projects in competition (SOHO, Cluster and Kepler), but stressed that "if the Executive could implement the STSP Cornerstone within 400 MAU, it would do so unless the SSAC expressed a strong negative opinion on this approach"."

- ^ Krige et al. 2000,page 217, "The supporters of Kepler had a good card in their hands, however, i.e. the high cost of the twin SOHO/Cluster mission, well above the 400 MAU ceiling."

- ^ Harvey 2003,page 211, "Several other mission possibilities were also discussed; for example, a Mars probe (Kepler)..."

- ^ Krige et al. 2000,page 217, "The decision was not however taken without some conflict. One of the new SSAC members, M. Ackerman, did not like the "inferiority situation" in which Kepler had found itself as aconsequence of the introduction of the STSP Cornerstone and insisted that the Mars mission should be maintained in the selection cycle."

- ^ Krige et al. 2000,page 219, "The SPC met on 6 February 1986, in the aftermath of the dramatic accident which had destroyed the Challenger Shuttle, killing its crew (28 January). This event threw a new shadow on the STSP programme: firstly, because SOHO was assumed to be eventually launched on the Space Shuttle..."

- ^ Krige et al. 2000,page 217, "After a dramatic discussion on the various options, the SSAC agreed that an STSP mission consisting of a descoped SOHO and a three-spacecraft Cluster should eventually be pursued..."

- ^ Krige et al. 2000,page 218–219, "The SSWG unanimously agreed to recommend the STSP programme [...] The SSAC, for their part, fully endorsed the SSWG recommendation [...] all SPC delegations finally approved the adoption of the STSP double mission into ESA's Scientific Programme..."

- ^ Krige et al. 2000,page 219, "ESA would also develop the SOHO spacecraft (including payload integration) for which NASA would provide testing, launch services and operations. European and US experiments would be included in SOHO and the first Cluster spacecraft."

- ^ Wilson 2005,page 160, "The Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO) is a cooperative project between ESA and NASA..."

- ^ 87.0 87.1 Krige et al. 2000,page 219, "In the event, a tentative agreement was reached with NASA in October that year, by which ESA would develop four identical Cluster spacecraft, one of which would be launched by NASA in 1993 into an equatorial orbit, thereby replacing NASA's "Equator" ISTP satellite now cancelled, and the three others would be launched in 1994 (free of charge) on an Ariane-5 demonstration flight."

- ^ Goddard Space Flight Center. Equator-S. Space Science Data Coordinated Archive. [15 July 2019]. (原始內容存檔於15 July 2019).

Equator-S is different from NASA's ISTP/EQUATOR spacecraft, which was dropped when the ISTP mission was re-scoped in late 1989.

- ^ 89.0 89.1 Bonnet 2004,page 203, "In response to a call for ideas for new missions released by ESA in 1982, a group of European and US scientists proposed adding a Titan Probe as an element of the US Cassini mission."

- ^ Harvey 2003,page 211, "Also in the melting pot for consideration were an ultraviolet observatory (Lyman), a very long baseline interferometry mission (Quasat)..."

- ^ Krige et al. 2000,page 220, "All three missions under consideration were recommended by the Working Groups for Phase-A study, the Titan probe for the Cassini mission by the SSWG and Lyman and Quasat by the AWG."

- ^ 92.0 92.1 92.2 Bonnet 2004,page 203–204, "The Titan Probe was eventually selected by ESA's SPC in Nov. 1998 (原文如此) as the first 'blue' mission of Horizon 2000, against four other missions: VESTA, LYMAN, QUASAT, and GRASP."

- ^ Bonnet 1988,page 87, "Vesta is a trilateral (USSR, CNES, and ESA) mission to the small bodies of the Solar System [...] Each spacecraft will fly-by a minimum of three asteroids [...] A cometary fly-by will also be included."

- ^ Bonnet 1988,page 93, "GRASP (Gamma-Ray Astronomy with Spectrometry and Positioning) is a fully European project."

- ^ Harvey 2003,page 211, "...a gamma ray observatory (GRASP) and a number of candidates for an asteroid mission (Agora, Vesta)."

- ^ Krige et al. 2000,page 220, "Later on, however, NASA informed ESA that because of budgets cuts, in the wake of the Challenger accident, they could no longer consider the Lyman and Quasat projects for the present."

- ^ Bonnet 2004,page 204, "At the end of the SPC meeting the Director of the Science Programme reminded delegations that the Saturn moon Titan had been discovered in 1655 by the Dutch astronomer Huygens. In response to the Swiss request, he therefore proposed that the European contribution to the American Cassini project henceforth by known as 'Huygens'."

- ^ ESF and NRC 1998,page 54, "The early definition of INTEGRAL attempted to combine the best features of the two earlier gamma-ray missions studied on both sides of the Atlantic [...] In June 1989, in response to the ESA call for new mission proposals, INTEGRAL was proposed jointly [...] on behalf of a consortium of institutes and laboratories in Europe and the United States."

- ^ ESF and NRC 1998,page 54, "The renewed discussions of INTEGRAL in Europe following the rejection of GRASP stemmed in part from the NASA Explorer competition of 1989 in which a U.S. gamma-ray spectroscopy mission, the Nuclear Astrophysics Explorer (NAE), had been selected for a Phase A study but then was not selected for flight."

- ^ ESF and NRC 1998,page 54, "It was envisioned as a fully-shared ESA-NASA partnership, a view supported by NASA Headquarters."

- ^ ESF and NRC 1998,page 54, "In December 1991, the Russian Academy of Sciences offered to provide a Proton launcher, free of charge, as a contribution in exchange for a share of the observing time."

- ^ ESF and NRC 1998,page 55, "Moreover, NASA had no previously identified INTEGRAL in its overall mission planning. Given this uncertainty, NASA was unable to make a firm commitment. [...] A suspicion arose within the U.S. space science community that funding the spectrometer would require funds be derived from the Explorer line."

- ^ ESF and NRC 1998,page 55, "At ESA's June 1993 meeting, the SPC approved INTEGRAL as ESA's M2 mission, based on an international cooperation in which Russia would provide the Proton launcher and NASA the spectrometer instrument, as well as a contribution to the ground segment."

- ^ Wilson 2005,page 236, "Integral was selected by the Agency's Science Programme Committee in 1993 as the M2 medium-size scientific mission. It was conceived as an observatory, with contributions from Russia (launch) and NASA (Deep Space Network ground stations)."

- ^ 105.0 105.1 ESF and NRC 1998,page 55, "The INTEGRAL mission had still not garnered broad U.S. support or a vocal constituency in the NASA space science advisory process for several reasons [...] the perception that INTEGRAL had never passed the required peer review in the Explorer competition..."

- ^ ESF and NRC 1998,page 55, "...early concerns of some astrophysists that the lack of detection of bright descrete sources of line emission [...] implied that the spectrometer planned for INTEGRAL might not be sensitive enough."

- ^ ESF and NRC 1998,page 55, "...it became increasingly clear that NASA could not support INTEGRAL at the $70 million level expected by U.S. PIs. [...] Finally in September 1994, a meeting between ESA and NASA led to the conclusion that NASA could not support the U.S. spectrometer PI."

- ^ ESF and NRC 1998,page 55, "The proposal was made possible because the Centre National d'Études Spatiales (CNES), the French national space agency, agreed to assume the financial burden resulting from NASA's withdrawal on the spectrometer..."

- ^ ESA confirms ROSETTA and FIRST in its long-term science programme. XMM-Newton Press Release. 8 November 1993: 43 [21 December 2016]. Bibcode:1993xmm..pres...43.. (原始內容存檔於21 December 2016).

- ^ Van Tran, J. Fundamental Parameters in Cosmology. Paris: Atlantica Séguier Frontières. 1998: 255 [2021-12-13]. ISBN 978-2-86332-233-8. (原始內容存檔於2021-12-29).

- ^ History of Planck - COBRAS/SAMBA: The Beginning of Planck. ESA Cosmos Portal. European Space Agency. December 2013 [25 December 2016]. (原始內容存檔於25 December 2016).

- ^ Vincent Minier; et al. Inventing a Space Mission: The Story of the Herschel Space Observatory. International Space Science Institute (Springer Publishing). 26 November 2017: 40 [2021-12-15]. ISBN 978-3-319-60023-9. (原始內容存檔於2021-12-16).

- ^ New approach for L-class mission candidates. ESA. 19 April 2011 [23 August 2019]. (原始內容存檔於2019-08-23).

- ^ ESA Science & Technology - JUICE. ESA. 8 November 2021 [10 November 2021]. (原始內容存檔於2019-09-21).

- ^ Athena: Mission Summary. ESA. 8 November 2021 [10 November 2021]. (原始內容存檔於2021-11-10).

- ^ LISA: Mission Summary. ESA. 8 November 2021 [10 November 2021]. (原始內容存檔於2021-11-10).

- ^ Solar Orbiter: Summary. ESA. 20 September 2018 [19 December 2018]. (原始內容存檔於2019-02-12).

- ^ Key milestone for Euclid mission, now ready for final assembly. ESA. 18 December 2018 [19 December 2018]. (原始內容存檔於2019-08-17).

- ^ Dark and bright: ESA chooses next two science missions. ESA. 4 October 2011 [23 August 2014]. (原始內容存檔於2019-08-17).

- ^ Gravitational wave mission selected, planet-hunting mission moves forward. ESA. 20 June 2017 [20 June 2017]. (原始內容存檔於2017-07-09).

- ^ ESA selects planet-hunting PLATO mission. ESA. 19 February 2014 [11 February 2015]. (原始內容存檔於2019-02-28).

- ^ Call for a Medium-size mission opportunity in ESA's Science Programme for a launch in 2025 (M4). ESA. 19 August 2014 [23 August 2014]. (原始內容存檔於2019-08-17).

- ^ Amos, Jonathan. Europe drops asteroid sample-return idea. BBC News. 18 March 2015 [16 April 2015]. (原始內容存檔於2021-12-17).

- ^ 124.0 124.1 Three candidates for ESA's next medium-class science mission. ESA. 4 June 2015 [4 June 2015]. (原始內容存檔於2019-08-23).

- ^ ESA's next science mission to focus on nature of exoplanets. ESA. 20 March 2018 [23 August 2019]. (原始內容存檔於2019-09-13).

- ^ Cosmic Vision M4 candidate missions: Presentation Event. ESA. 5 May 2017 [19 September 2017]. (原始內容存檔於2019-08-17).

- ^ 127.0 127.1 ESA selects revolutionary Venus mission EnVision. ESA. 10 June 2021 [11 June 2021]. (原始內容存檔於2021-12-25).

- ^ ESA selects three new mission concepts for study. ESA. 7 May 2018 [10 May 2018]. (原始內容存檔於2019-10-13).

- ^ Call for a small mission opportunity in ESA's science programme for a launch in 2017. ESA. 9 March 2012 [20 February 2014]. (原始內容存檔於2013-03-13).

- ^ S-class mission letters of intent. ESA. 16 April 2012 [20 February 2014].

- ^ CHEOPS Mission Status & Summary. University of Bern. July 2018 [2 November 2018]. (原始內容存檔於2019-08-13).

- ^ Exoplanet mission launch slot announced. ESA. 23 November 2018 [19 December 2018]. (原始內容存檔於2019-04-18).

- ^ ESA and Chinese Academy of Sciences to study SMILE as joint mission. ESA. 4 June 2015 [5 August 2015]. (原始內容存檔於2019-08-13).

- ^ SMILE. Open University. 14 April 2021 [18 May 2021]. (原始內容存檔於2021-12-10).

- ^ Hasinger, Günther. The ESA Science Programme - ESSC Plenary Meeting (PDF). ESA. 23 May 2018 [8 July 2018]. (原始內容存檔 (PDF)於2021-06-04).

- ^ Gater, Will. Comet mission given green light by European Space Agency. Physics World. 21 June 2019 [23 August 2019]. (原始內容存檔於2021-12-15).

- ^ Lakdawalla, Emily. ESA to Launch Comet Interceptor Mission in 2028. The Planetary Society. 21 June 2019 [23 August 2019]. (原始內容存檔於2019-11-20).

- ^ O'Callaghan, Jonathan. European Comet Interceptor Could Visit an Interstellar Object

. Scientific American. 24 June 2019 [23 August 2019]. (原始內容存檔於2021-12-15).

. Scientific American. 24 June 2019 [23 August 2019]. (原始內容存檔於2021-12-15).

- ^ 139.0 139.1 Policy for Missions of Opportunity in the ESA Science Directorate. ESA. 5 February 2019 [26 June 2019]. (原始內容存檔於2019-07-29).

- ^ SPICA - A space infrared telescope for cosmology and astrophysics. ESA. 19 February 2014 [20 February 2014]. (原始內容存檔於2013-05-12).

- ^ Voyage 2050 – Long-term planning of the ESA Science Programme. ESA. 28 February 2019 [26 June 2019]. (原始內容存檔於2022-01-01).

- ^ Call for White Papers for the Voyage 2050 long-term plan in the ESA Science Programme (PDF). ESA. 4 March 2019 [26 June 2019]. (原始內容存檔 (PDF)於26 June 2019).

- ^ Voyage 2050 sets sail: ESA chooses future science mission themes. ESA. 11 June 2021 [12 June 2021]. (原始內容存檔於2021-12-15).

外部連結[編輯]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 機構概要 | |

|---|---|

| 類型 | 航天機構 |