用戶:PhiLiP/童話

童話是一種短篇敘事作品,在英語被稱為「Fairy tale」,法語為「conte de fée」,德語為「Märchen」,意大利語為「fiaba」,波蘭語為「baśń」,瑞典語為「saga」。童話的人物通常由小仙子、哥布林、精靈、巨怪、巨人或地精等民俗角色構成,故事中常出現巫術或咒語。童話故事往往有着一系列難以置信的情節。

在脫離原意的環境中,「童話」一詞亦被用於比喻不同尋常的快樂和幸福,例如「童話般的結局」(意為完美結局)[1]、「童話般的愛情」(儘管並非所有童話都有完美結局)。此外,在口語中,「童話」還可用於形容荒誕、牽強的故事。

在許多文化中,邪靈與女巫常被認為是存在於真實世界的,這時童話就有可能變成傳說,如此一來說故事和聽故事的人也更會覺得故事是一段史實。但是和傳說與史詩有所區別的是,童話並不會過多地提及宗教、具體的地點、人物和事件,童話故事發生在「很早以前」,而不是具體的時代。[2]

童話具有口述和寫作兩種形式。童話的歷史很難追溯,因為只有寫作形式的童話才會得以流傳。但雖如此,可考的文學作品卻也證明童話至少有數千年歷史,儘管童話在古代並未被視為獨立的文學類型:「童話」一詞是多爾諾瓦夫人最先使用的。今天的許多童話故事,都是從幾百年前的古老故事演變而來,並在世界各地不同文化的薰陶下,產生了多種多樣的版本。[3]在現今,藝術家們仍然還在創作童話及其衍生作品。

早期童話的讀者既有兒童也有成人。然而,早在女才子文風出現之時,童話的主體受眾便已是兒童了;格林兄弟就是以《獻給孩子和家庭的童話》為其文集命名的,隨着時間的推移,童話和兒童的聯繫也越來越緊密。

在童話的分類上,民俗學家採用了各種不同的方式。其中最知名的是阿爾奈-湯普森分類法和弗拉基米爾·普羅普的形態分析法。其他的民俗學家詮釋了童話故事的意義,但目前這些解釋均尚未確立任何學派。

定義

[編輯]儘管童話與其他民間故事有着截然不同的差別,但如何將一部作品定義為童話卻仍然備受爭議。[4]小仙子或其他巫術生物應是童話的必然成分。[5]照一般的說法,動物寓言和其他的一些民間故事也算是童話,但具體到小仙子和/或其他巫術生物(如精靈、哥布林、巨魔、巨人等)上,到底按何種出場程度可將作品歸類為童話,學者們持有不同的意見。弗拉基米爾·普羅普在其《民間故事形態學》(Morphology of the Folktale)一書中,非議了童話故事和動物故事的常見區別,因為許多故事都同時包含有奇幻和動物這兩個因素。[6]然而,在為其分析挑選作品時,普羅普使用了阿爾奈-湯普森分類法300-749類的全部俄羅斯民間故事來構成故事集。[7]並使用自己的分析方式,根據故事的情節元素來判斷其是否屬於童話。這種分析方法本身便遭到了質疑,因其無法簡單地適用在不帶探索情節的故事上;此外,相同的情節元素亦會在非童話作品中出現。[8]

| “ | 有人問我,什麼是童話?我會說,讀讀《渦堤孩》吧,那就是童話……在我讀過的所有童話中,《渦堤孩》無疑是最優美的。[9] | ” |

| ——喬治·麥克唐納,《幻想集》(The Fantastic Imagination) | ||

正如斯蒂思·湯普森指出的那樣,動物和巫術在童話故事中所佔的比例要高於小仙子。[10]然而,有動物出現的故事並不一定是童話,特別是當動物被明顯用作人類象徵時,譬如寓言故事。[11]

在《論童話故事》一文中,J·R·R·托爾金認為可以根據定義來排除不屬於「童話」的作品;他將童話定義為人在「仙境」(Faërie)中的奇遇:仙境裏居住着小仙子、童話里的王子和公主、矮人與精靈;在童話中,不僅要有神奇的生物,還要有着各種各樣的奇蹟。[12]然而,這篇文章將一些常被視為童話的故事排除在童話之外,例如曾被安德魯·朗格收入《淡紫色童話書》中的故事《猴子的心》。[11]

Steven Swann Jones identified the presence of magic as the feature by which fairy tales can be distinguished from other sorts of folktales.[13] Davidson and Chaudri identify "transformation" as the key feature of the genre.[14] From a psychological point of view, Jean Chiriac argued for the necessity of the fantastic in these narratives.[15]

Some folklorists prefer to use the German term Märchen or "wonder tale"[14] to refer to the genre, a practice given weight by the definition of Thompson in his 1977 edition of The Folktale: "a tale of some length involving a succession of motifs or episodes. It moves in an unreal world without definite locality or definite creatures and is filled with the marvelous. In this never-never land, humble heroes kill adversaries, succeed to kingdoms and marry princesses."[16] The characters and motifs of fairy tales are simple and archetypal: princesses and goose-girls; youngest sons and gallant princes; ogres, giants, dragons, and trolls; wicked stepmothers and false heroes; fairy godmothers and other magical helpers, often talking horses, or foxes, or birds; glass mountains; and prohibitions and breaking of prohibitions.[17]

In terms of aesthetic values, Italo Calvino cited the fairy tale as a prime example of "quickness" in literature, because of the economy and concision of the tales.[18]

History of the genre

[編輯]Originally, stories we would now call fairy tales were not marked out as a separate genre. The German term "Märchen" literally translates as "tale"—not any specific type of tale. The genre was first marked out by writers of the Renaissance, stabilized through the works of many subsequent writers, and emerged as an unquestioned genre in the works of the Brothers Grimm.[19] In this evolution, the name was coined when the précieuses took up writing literary stories; Madame d'Aulnoy invented the term conte de fée, or fairy tale.[20]

Before the definition of the genre of fantasy, many works that would now be classified as fantasy were termed "fairy tales", including Tolkien's The Hobbit, George Orwell's Animal Farm, and L. Frank Baum's The Wonderful Wizard of Oz.[21] Indeed, Tolkien's "On Fairy-Stories" includes discussions of world-building and is considered a vital part of fantasy criticism. Although fantasy, particularly the sub-genre of fairytale fantasy, draws heavily on fairy tale motifs,[22] the genres are now regarded as distinct.

Folk and literary

[編輯]

The fairy tale, told orally, is a sub-class of the folktale. Many writers have written in the form of the fairy tale. These are the literary fairy tales, or Kunstmärchen.[5] The oldest forms, from Panchatantra to the Pentamerone, show considerable reworking from the oral form.[23] The Brothers Grimm were among the first to try to preserve the features of oral tales. Yet the stories printed under the Grimm name have been considerably reworked to fit the written form.[24]

Literary fairy tales and oral fairy tales freely exchanged plots, motifs, and elements with one another and with the tales of foreign lands.[25] Many 18th-century folklorists attempted to recover the "pure" folktale, uncontaminated by literary versions. Yet while oral fairy tales likely existed for thousands of years before the literary forms, there is no pure folktale. And each literary fairy tale draws on folk traditions, if only in parody.[26] This makes it impossible to trace forms of transmission of a fairy tale. Oral story-tellers have been known to read literary fairy tales to increase their own stock of stories and treatments.[27]

History

[編輯]

The oral tradition of the fairy tale came long before the written page. Tales were told or enacted dramatically, rather than written down, and handed down from generation to generation. Because of this, the history of their development is necessarily obscure.[28] The oldest known written fairy tales stem from ancient Egypt, c. 1300 BC (ex. The Tale of Two Brothers),[29] and fairy tales appear, now and again, in written literature throughout literate cultures, as in The Golden Ass, which includes Cupid and Psyche (Roman, 100–200 AD),[30] or the Panchatantra (India 3rd century BCE),[30] but it is unknown to what extent these reflect the actual folk tales even of their own time. The stylistic evidence indicates that these, and many later collections, reworked folk tales into literary forms.[23] What they do show is that the fairy tale has ancient roots, older than the Arabian Nights collection of magical tales (compiled circa 1500 AD),[30] such as Vikram and the Vampire, and Bel and the Dragon. Besides such collections and individual tales, in China, Taoist philosophers such as Liezi and Zhuangzi recounted fairy tales in their philosophical works.[31] In the broader definition of the genre, the first famous Western fairy tales are those of Aesop (6th century BC) in ancient Greece.

Allusions to fairy tales appear plentifully in Geoffrey Chaucer's The Canterbury Tales, Edmund Spenser's The Faerie Queene, and the plays of William Shakespeare.[32] King Lear can be considered a literary variant of fairy tales such as Water and Salt and Cap O' Rushes.[33] The tale itself resurfaced in Western literature in the 16th and 17th centuries, with The Facetious Nights of Straparola by Giovanni Francesco Straparola (Italy, 1550 and 1553),[30] which contains many fairy tales in its inset tales, and the Neapolitan tales of Giambattista Basile (Naples, 1634–6),[30] which are all fairy tales.[34] Carlo Gozzi made use of many fairy tale motifs among his Commedia dell'Arte scenarios,[35] including among them one based on The Love For Three Oranges (1761).[36] Simultaneously, Pu Songling, in China, included many fairy tales in his collection, Strange Stories from a Chinese Studio (published posthumously, 1766).[31] The fairy tale itself became popular among the précieuses of upper-class France (1690–1710),[30] and among the tales told in that time were the ones of La Fontaine and the Contes of Charles Perrault (1697), who fixed the forms of Sleeping Beauty and Cinderella.[37] Although Straparola's, Basile's and Perrault's collections contain the oldest known forms of various fairy tales, on the stylistic evidence, all the writers rewrote the tales for literary effect.[38]

The first collectors to attempt to preserve not only the plot and characters of the tale, but also the style in which they were told, were the Brothers Grimm, collecting German fairy tales; ironically, this meant although their first edition (1812 & 1815)[30] remains a treasure for folklorists, they rewrote the tales in later editions to make them more acceptable, which ensured their sales and the later popularity of their work.[39]

Such literary forms did not merely draw from the folktale, but also influenced folktales in turn. The Brothers Grimm rejected several tales for their collection, though told orally to them by Germans, because the tales derived from Perrault, and they concluded they were thereby French and not German tales; an oral version of Bluebeard was thus rejected, and the tale of Briar Rose, clearly related to Perrault's Sleeping Beauty, was included only because Jacob Grimm convinced his brother that the figure of Brynhildr, from much earlier Norse mythology, proved that the sleeping princess was authentically Germanic folklore.[40]

This consideration of whether to keep Sleeping Beauty reflected a belief common among folklorists of the 19th century: that the folk tradition preserved fairy tales in forms from pre-history except when "contaminated" by such literary forms, leading people to tell inauthentic tales.[41] The rural, illiterate, and uneducated peasants, if suitably isolated, were the folk and would tell pure folk tales.[42] Sometimes they regarded fairy tales as a form of fossil, the remnants of a once-perfect tale.[43] However, further research has concluded that fairy tales never had a fixed form, and regardless of literary influence, the tellers constantly altered them for their own purposes.[44]

The work of the Brothers Grimm influenced other collectors, both inspiring them to collect tales and leading them to similarly believe, in a spirit of romantic nationalism, that the fairy tales of a country were particularly representative of it, to the neglect of cross-cultural influence. Among those influenced were the Russian Alexander Afanasyev (first published in 1866),[30] the Norwegians Peter Christen Asbjørnsen and Jørgen Moe (first published in 1845),[30] the Romanian Petre Ispirescu (first published in 1874), the English Joseph Jacobs (first published in 1890),[30] and Jeremiah Curtin, an American who collected Irish tales (first published in 1890).[26] Ethnographers collected fairy tales over the world, finding similar tales in Africa, the Americas, and Australia; Andrew Lang was able to draw on not only the written tales of Europe and Asia, but those collected by ethnographers, to fill his "coloured" fairy books series.[45] They also encouraged other collectors of fairy tales, as when Yei Theodora Ozaki created a collection, Japanese Fairy Tales (1908), after encouragement from Lang.[46] Simultaneously, writers such as Hans Christian Andersen and George MacDonald continued the tradition of literary fairy tales. Andersen's work sometimes drew on old folktales, but more often deployed fairytale motifs and plots in new tales.[47] MacDonald incorporated fairytale motifs both in new literary fairy tales, such as The Light Princess, and in works of the genre that would become fantasy, as in The Princess and the Goblin or Lilith.[48]

Cross-cultural transmission

[編輯]Two theories of origins have attempted to explain the common elements in fairy tales found spread over continents. One is that a single point of origin generated any given tale, which then spread over the centuries; the other is that such fairy tales stem from common human experience and therefore can appear separately in many different origins.[49]

Fairy tales with very similar plots, characters, and motifs are found spread across many different cultures. Many researchers hold this to be caused by the spread of such tales, as people repeat tales they have heard in foreign lands, although the oral nature makes it impossible to trace the route except by inference.[50] Folklorists have attempted to determine the origin by internal evidence, which can not always be clear; Joseph Jacobs, comparing the Scottish tale The Ridere of Riddles with the version collected by the Brothers Grimm, The Riddle, noted that in The Ridere of Riddles one hero ends up polygamously married, which might point to an ancient custom, but in The Riddle, the simpler riddle might argue greater antiquity.[51]

Folklorists of the "Finnish" (or historical-geographical) school attempted to place fairy tales to their origin, with inconclusive results.[52] Sometimes influence, especially within a limited area and time, is clearer, as when considering the influence of Perrault's tales on those collected by the Brothers Grimm. Little Briar-Rose appears to stem from Perrault's Sleeping Beauty, as the Grimms' tale appears to be the only independent German variant.[53] Similarly, the close agreement between the opening of Grimms' version of Little Red Riding Hood and Perrault's tale points to an influence—although Grimms' version adds a different ending (perhaps derived from The Wolf and the Seven Young Kids).[54]

Fairy tales also tend to take on the color of their location, through the choice of motifs, the style in which they are told, and the depiction of character and local color.[55]

Association with children

[編輯]Originally, adults were the audience of a fairy tale just as often as children.[56] Literary fairy tales appeared in works intended for adults, but in the 19th and 20th centuries the fairy tale became associated with children's literature.

The précieuses, including Madame d'Aulnoy, intended their works for adults, but regarded their source as the tales that servants, or other women of lower class, would tell to children.[57] Indeed, a novel of that time, depicting a countess's suitor offering to tell such a tale, has the countess exclaim that she loves fairy tales as if she were still a child.[58] Among the late précieuses, Jeanne-Marie Le Prince de Beaumont redacted a version of Beauty and the Beast for children, and it is her tale that is best known today.[59] The Brothers Grimm titled their collection Children's and Household Tales and rewrote their tales after complaints that they were not suitable for children.[60]

In the modern era, fairy tales were altered so that they could be read to children. The Brothers Grimm concentrated mostly on eliminating sexual references;[61] Rapunzel, in the first edition, revealed the prince's visits by asking why her clothing had grown tight, thus letting the witch deduce that she was pregnant, but in subsequent editions carelessly revealed that it was easier to pull up the prince than the witch.[62] On the other hand, in many respects, violence – particularly when punishing villains – was increased.[63] Other, later, revisions cut out violence; J. R. R. Tolkien noted that The Juniper Tree often had its cannibalistic stew cut out in a version intended for children.[64] The moralizing strain in the Victorian era altered the classical tales to teach lessons, as when George Cruikshank rewrote Cinderella in 1854 to contain temperance themes. His acquaintance Charles Dickens protested, "In an utilitarian age, of all other times, it is a matter of grave importance that fairy tales should be respected."[65][66]

Psychoanalysts such as Bruno Bettelheim, who regarded the cruelty of older fairy tales as indicative of psychological conflicts, strongly criticized this expurgation, because it weakened their usefulness to both children and adults as ways of symbolically resolving issues.[67]

The adaptation of fairy tales for children continues. Walt Disney's influential Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs was largely (although certainly not solely) intended for the children's market.[68] The anime Magical Princess Minky Momo draws on the fairy tale Momotarō.[69] Jack Zipes has spent many years working to make the older traditional tales accessible to modern readers and their children.[70]

In Waldorf schools, fairy tales are used in the first grade as a central part of the curriculum. Rudolf Steiner's work on human development claims that at age six to seven, the mind of a child is best taught through storytelling. The archetypes and magical nature of fairy tales appeals strongly to children of these ages. The nature of fairy tales, following the oral tradition, enhances the child's ability to visualize a spoken narrative, as well as to remember the story as heard.[來源請求]

Contemporary tales

[編輯]Literary

[編輯]

In contemporary literature, many authors have used the form of fairy tales for various reasons, such as examining the human condition from the simple framework a fairytale provides.[71] Some authors seek to recreate a sense of the fantastic in a contemporary discourse.[72] Some writers use fairy tale forms for modern issues;[73] this can include using the psychological dramas implicit in the story, as when Robin McKinley retold Donkeyskin as the novel Deerskin, with emphasis on the abusive treatment the father of the tale dealt to his daughter.[74] Sometimes, especially in children's literature, fairy tales are retold with a twist simply for comic effect, such as The Stinky Cheese Man by Jon Scieszka and The ASBO Fairy Tales by Chris Pilbeam. A common comic motif is a world where all the fairy tales take place, and the characters are aware of their role in the story,[75] such as in the film series Shrek.

Other authors may have specific motives, such as multicultural or feminist reevaluations of predominantly Eurocentric masculine-dominated fairy tales, implying critique of older narratives.[76] The figure of the damsel in distress has been particularly attacked by many feminist critics. Examples of narrative reversal rejecting this figure include The Paperbag Princess by Robert Munsch, a picture book aimed at children in which a princess rescues a prince, and Angela Carter's The Bloody Chamber, which retells a number of fairy tales from a female point of view.[來源請求]

One use of the genre occurred in a military technology journal named Defense AT&L, which published an article as a fairytale titled Optimizing Bi-Modal Signal/Noise Ratios. Written by Maj. Dan Ward (USAF), the story uses a fairy named Garble to represent breakdowns in communication between operators and technology developers.[77] Ward's article was heavily influenced by George MacDonald.

Other notable figures who have employed fairy tales include Oscar Wilde, A. S. Byatt, Jane Yolen, Terri Windling, Donald Barthelme, Robert Coover, Margaret Atwood, Kate Bernheimer, Espido Freire, Tanith Lee, James Thurber, Robin McKinley, Isaac Bashevis Singer, Kelly Link, Bruce Holland Rogers, Donna Jo Napoli, Cameron Dokey, Robert Bly, Gail Carson Levine, Annette Marie Hyder, Jasper Fforde and many others.[來源請求]

It may be hard to lay down the rule between fairy tales and fantasies that use fairy tale motifs, or even whole plots, but the distinction is commonly made, even within the works of a single author: George MacDonald's Lilith and Phantastes are regarded as fantasies, while his "The Light Princess", "The Golden Key", and "The Wise Woman" are commonly called fairy tales. The most notable distinction is that fairytale fantasies, like other fantasies, make use of novelistic writing conventions of prose, characterization, or setting.[78]

Film

[編輯]Fairy tales have been enacted dramatically; records exist of this in commedia dell'arte,[79] and later in pantomime.[80] The advent of cinema has meant that such stories could be presented in a more plausible manner, with the use of special effects and animation; the Disney movie Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs in 1937 was a ground-breaking film for fairy tales and, indeed, fantasy in general.[68] Disney's influence helped establish this genre as a children's genre, and has been blamed for simplification of fairy tales ending in situations where everything goes right, as opposed to the pain and suffering — and sometimes unhappy endings — of many folk fairy tales.[74]

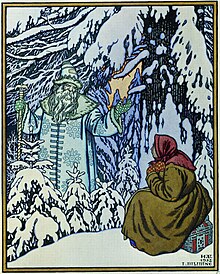

Many filmed fairy tales have been made primarily for children, from Disney's later works to Aleksandr Rou's retelling of Vasilissa the Beautiful, the first Soviet film to use Russian folk tales in a big-budget feature.[81] Others have used the conventions of fairy tales to create new stories with sentiments more relevant to contemporary life, as in Labyrinth,[82] My Neighbor Totoro, the films of Michel Ocelot,[83] and Happily N'Ever After.

Other works have retold familiar fairy tales in a darker, more horrific or psychological variant aimed primarily at adults. Notable examples are Jean Cocteau's Beauty and the Beast[84] and The Company of Wolves, based on an Angela Carter's retelling of Little Red Riding Hood.[85] Likewise, Princess Mononoke,[86] Pan's Labyrinth,[87] Suspiria, and Spike[88] create new stories in this genre from fairy tale and folklore motifs.

In comics and animated TV series, The Sandman, Revolutionary Girl Utena, Princess Tutu, Fables and MÄR all make use of standard fairy tale elements to various extents but are more accurately categorised as fairytale fantasy due to the definite locations and characters which a longer narrative requires.

A more modern cinematic fairy tale would be Luchino Visconti’s Le Notti Bianche, starring Marcello Mastroianni before he became a superstar. It involves many of the romantic conventions of fairy tales, yet it takes place in post-World War II Italy, and it ends realistically.

Motifs

[編輯]Any comparison of fairy tales quickly discovers that many fairy tales have features in common with each other. Two of the most influential classifications are those of Antti Aarne, as revised by Stith Thompson into the Aarne-Thompson classification system, and Vladimir Propp's Morphology of the Folk Tale.

Aarne-Thompson

[編輯]This system groups fairy and folk tales according to their overall plot. Common, identifying features are picked out to decide which tales are grouped together. Much therefore depends on what features are regarded as decisive.

For instance, tales like Cinderella – in which a persecuted heroine, with the help of the fairy godmother or similar magical helper, attends an event (or three) in which she wins the love of a prince and is identified as his true bride – are classified as type 510, the persecuted heroine. Some such tales are The Wonderful Birch, Aschenputtel, Katie Woodencloak, The Story of Tam and Cam, Ye Xian, Cap O' Rushes, Catskin, Fair, Brown and Trembling, Finette Cendron, Allerleirauh, and Tattercoats.

Further analysis of the tales shows that in Cinderella, The Wonderful Birch, The Story of Tam and Cam, Ye Xian, and Aschenputtel, the heroine is persecuted by her stepmother and refused permission to go to the ball or other event, and in Fair, Brown and Trembling and Finette Cendron by her sisters and other female figures, and these are grouped as 510A; while in Cap O' Rushes, Catskin, and Allerleirauh, the heroine is driven from home by her father's persecutions, and must take work in a kitchen elsewhere, and these are grouped as 510B. But in Katie Woodencloak, she is driven from home by her stepmother's persecutions and must take service in a kitchen elsewhere, and in Tattercoats, she is refused permission to go to the ball by her grandfather. Given these features common with both types of 510, Katie Woodencloak is classified as 510A because the villain is the stepmother, and Tattercoats as 510B because the grandfather fills the father's role.

This system has its weaknesses in the difficulty of having no way to classify subportions of a tale as motifs. Rapunzel is type 310 (The Maiden in the Tower), but it opens with a child being demanded in return for stolen food, as does Puddocky; but Puddocky is not a Maiden in the Tower tale, while The Canary Prince, which opens with a jealous stepmother, is.

It also lends itself to emphasis on the common elements, to the extent that the folklorist describes The Black Bull of Norroway as the same story as Beauty and the Beast. This can be useful as a shorthand but can also erase the coloring and details of a story.[89]

Morphology

[編輯]Vladimir Propp specifically studied a collection of Russian fairy tales, but his analysis has been found useful for the tales of other countries.[90]

Having criticized Aarne-Thompson type analysis for ignoring what motifs did in stories, and because the motifs used were not clearly distinct,[91] he analyzed the tales for the function each character and action fulfilled and concluded that a tale was composed of thirty-one elements and eight character types. While the elements were not all required for all tales, when they appeared they did so in an invariant order — except that each individual element might be negated twice, so that it would appear three times, as when, in Brother and Sister, the brother resists drinking from enchanted streams twice, so that it is the third that enchants him.[92]

One such element is the donor who gives the hero magical assistance, often after testing him.[93] In The Golden Bird, the talking fox tests the hero by warning him against entering an inn and, after he succeeds, helps him find the object of his quest; in The Boy Who Drew Cats, the priest advised the hero to stay in small places at night, which protects him from an evil spirit; in Cinderella, the fairy godmother gives Cinderella the dresses she needs to attend the ball, as their mothers' spirits do in Bawang Putih Bawang Merah and The Wonderful Birch; in The Fox Sister, a Buddhist monk gives the brothers magical bottles to protect against the fox spirit. The roles can be more complicated.[94] In The Red Ettin, the role is split into the mother – who offers the hero the whole of a journey cake with her curse or half with her blessing – and when he takes the half, a fairy who gives him advice; in Mr Simigdáli, the sun, the moon, and the stars all give the heroine a magical gift. Characters who are not always the donor can act like the donor.[95] In Kallo and the Goblins, the villain goblins also give the heroine gifts, because they are tricked; in Schippeitaro, the evil cats betray their secret to the hero, giving him the means to defeat them. Other fairy tales, such as The Story of the Youth Who Went Forth to Learn What Fear Was, do not feature the donor.

Analogies have been drawn between this and the analysis of myths into the Hero's journey.[96]

This analysis has been criticized for ignoring tone, mood, characters and, indeed, anything that differentiates one fairy tale from another.[97]

Interpretations

[編輯]Many variants, especially those intended for children, have had morals attached. Perrault concluded his versions with one, although not always completely moral: Cinderella concludes with the observation that her beauty and character would have been useless without her godmother, reflecting the importance of social connections, but could symbolize a spiritual meaning.[98]

Many fairy tales have been interpreted for their (purported) significance. One mythological interpretation claimed that many fairy tales, including Hansel and Gretel, Sleeping Beauty, and The Frog King, all were solar myths; this mode of interpretation is rather less popular now.[99] Many have also been subjected to Freudian, Jungian, and other psychological analysis, but no mode of interpretation has ever established itself definitively.

Specific analyses have often been criticized for lending great importance to motifs that are not, in fact, integral to the tale; this has often stemmed from treating one instance of a fairy tale as the definitive text, where the tale has been told and retold in many variations.[100] In variants of Bluebeard, the wife's curiosity is betrayed by a blood-stained key, by an egg's breaking, or by the singing of a rose she wore, without affecting the tale, but interpretations of specific variants have claimed that the precise object is integral to the tale.[101]

Other folklorists have interpreted tales as historical documents. Many German folklorists, believing the tales to have been preserved from ancient times, used Grimms' tales to explain ancient customs.[102] Other folklorists have explained the figure of the wicked stepmother historically: many women did die in childbirth, their husbands remarried, and the new stepmothers competed with the children of the first marriage for resources.[103]

Compilations

[編輯]- See also: Collections of fairy tales

Authors and works:

- Andrew Lang's Fairy Books (Scotland, 1889–1910)

- Fairy Tales (USA, 1965) by E. E. Cummings

- Giovanni Francesco Straparola (Italy, 16th century)

- Grimm's Fairy Tales (Germany, 1812–1857)

- Hans Christian Andersen (Denmark, 1805–1875)

- Fairy Tales, Now First Collected: To which are prefixed two dissertations: 1. On Pygmies. 2. On Fairies (England, 1831) by Joseph Ritson

- Italian Folktales (Italy, 1956) by Italo Calvino

- Joseph Jacobs (1854–1916)

- Legende sau basmele românilor (Romania, 1874) by Petre Ispirescu

- Madame d'Aulnoy (France, 1650–1705)

- Norwegian Folktales (Norway, 1845–1870) by Peter Christen Asbjørnsen and Jørgen Moe

- Narodnye russkie skazki (Russia, 1855–1863) by Alexander Afanasyev

- Pentamerone (Italy, 1634–1636) by Giambattista Basile

- Charles Perrault (France, 1628–1703)

- Panchatantra (India, 3rd century BCE)

- Popular Tales of the West Highlands (Scotland, 1862) by John Francis Campbell

- Ruth Manning-Sanders (Wales, 1886–1988)

- Kunio Yanagita (Japan, 1875–1962)

- World Tales (United Kingdom, 1979) by Idries Shah

See also

[編輯]Notes

[編輯]- ^ Merriam-Webster definition of "fairy tale"

- ^ Catherine Orenstein, Little Red Riding Hood Uncloaked, p. 9. ISBN 0-465-04125-6

- ^ Gray, Richard. "Fairy tales have ancient origin." Telegraph.co.uk. 5 September 2009.

- ^ Heidi Anne Heiner, "What Is a Fairy Tale?"

- ^ 5.0 5.1 Terri Windling, "Les Contes de Fées: The Literary Fairy Tales of France"

- ^ Vladimir Propp, Morphology of the Folk Tale, p. 5. ISBN 0-292-78376-0.

- ^ Propp, p. 19.

- ^ Steven Swann Jones, The Fairy Tale: The Magic Mirror of Imagination, Twayne Publishers, New York, 1995, p. 15. ISBN 0-8057-0950-9.

- ^ 原文:「Were I asked, what is a fairytale? I should reply, Read Undine: that is a fairytale ... of all fairytales I know, I think Undine the most beautiful.」

- ^ Stith Thompson, The Folktale, p 55, University of California Press, Berkeley Los Angeles London, 1977.

- ^ 11.0 11.1 J. R. R. Tolkien, "論童話故事" , The Tolkien Reader, p. 15.

- ^ Tolkien, pp. 10–11.

- ^ The Fairy Tale: The Magic Mirror of the Imagination. Routledge, 2002, p. 8.

- ^ 14.0 14.1 A companion to the fairy tale. By Hilda Ellis Davidson, Anna Chaudhri. Boydell & Brewer 2006. p. 39.

- ^ http://www.freudfile.org/psychoanalysis/fairy_tales.html

- ^ Stith Thompson, The Folktale, 1977 (Thompson: 8).

- ^ A. S. Byatt, "Introduction" p. xviii, Maria Tatar, ed. The Annotated Brothers Grimm, ISBN 0-393-05848-4.

- ^ Italo Calvino, Six Memoes for the Next Millennium, pp. 36–37. ISBN 0-674-81040-6.

- ^ Jack Zipes, The Great Fairy Tale Tradition: From Straparola and Basile to the Brothers Grimm, pp. xi-xii, ISBN 0-393-97636-X.

- ^ Zipes, The Great Fairy Tale Tradition: From Straparola and Basile to the Brothers Grimm, p. 858.

- ^ Brian Attebery, The Fantasy Tradition in American Literature, p. 83, ISBN 0-253-35665-2.

- ^ Philip Martin, The Writer's Guide of Fantasy Literature: From Dragon's Liar to Hero's Quest, pp. 38–42, ISBN 0-871116-195-8.

- ^ 23.0 23.1 Swann Jones, p. 35.

- ^ Brian Attebery, The Fantasy Tradition in American Literature, p. 5, ISBN 0-253-35665-2.

- ^ Zipes, The Great Fairy Tale Tradition: From Straparola and Basile to the Brothers Grimm, p. xii.

- ^ 26.0 26.1 Zipes, The Great Fairy Tale Tradition: From Straparola and Basile to the Brothers Grimm, p. 846.

- ^ Linda Degh, "What Did the Grimm Brothers Give To and Take From the Folk?" p. 73, James M. McGlathery, ed., The Brothers Grimm and Folktale, The Three Bears.ISBN 0-252-01549-5.

- ^ Jack Zipes, When Dreams Came True: Classical Fairy Tales and Their Tradition, p. 2. ISBN 0-415-92151-1.

- ^ John Grant and John Clute, The Encyclopedia of Fantasy, "Fairytale," p. 331. ISBN 0-312-19869-8.

- ^ 30.00 30.01 30.02 30.03 30.04 30.05 30.06 30.07 30.08 30.09 Heidi Anne Heiner, "Fairy Tale Timeline"

- ^ 31.0 31.1 Moss Roberts, "Introduction", p. xviii, Chinese Fairy Tales & Fantasies. ISBN 0-394-73994-9.

- ^ Zipes, When Dreams Came True: Classical Fairy Tales and Their Tradition, p. 11.

- ^ Soula Mitakidou and Anthony L. Manna, with Melpomeni Kanatsouli, Folktales from Greece: A Treasury of Delights, p. 100, Libraries Unlimited, Greenwood Village CO, 2002, ISBN 1-56308-908-4.

- ^ Swann Jones, p. 38.

- ^ Terri Windling, White as Ricotta, Red as Wine: The Magic Lore of Italy"

- ^ Italo Calvino, Italian Folktales, p. 738. ISBN 0-15-645489-0.

- ^ Zipes, When Dreams Came True: Classical Fairy Tales and Their Tradition, pp. 38–42.

- ^ Swann Jones, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Swann Jones, p. 40.

- ^ G. Ronald Murphy, The Owl, The Raven, and the Dove: The Religious Meaning of the Grimms' Magic Fairy Tales, ISBN 0195151690.

- ^ Zipes, When Dreams Came True: Classical Fairy Tales and Their Tradition, p. 77.

- ^ Degh, pp. 66–67.

- ^ Iona and Peter Opie, The Classic Fairy Tales p. 17. ISBN 0-19-211550-6.

- ^ Jane Yolen, p. 22, Touch Magic. ISBN 0-87483-591-7.

- ^ Andrew Lang, The Brown Fairy Book, "Preface"

- ^ Yei Theodora Ozaki, Japanese Fairy Tales, "Preface"

- ^ Grant and Clute, "Hans Christian Andersen," pp. 26–27.

- ^ Grant and Clute, "George MacDonald," p. 604.

- ^ Orenstein, pp. 77–78.

- ^ Zipes, The Great Fairy Tale Tradition: From Straparola and Basile to the Brothers Grimm, p. 845.

- ^ Joseph Jacobs, More Celtic Fairy Tales. London: David Nutt, 1894, "Notes and References"

- ^ Calvino, Italian Folktales, p. xx.

- ^ Harry Velten, "The Influences of Charles Perrault's Contes de ma Mère L'oie on German Folklore", p. 962, Jack Zipes, ed., The Great Fairy Tale Tradition: From Straparola and Basile to the Brothers Grimm.

- ^ Velten, pp. 966–67.

- ^ Calvino, Italian Folktales, p. xxi.

- ^ Zipes, When Dreams Came True: Classical Fairy Tales and Their Tradition, p. 1.

- ^ Lewis Seifert, "The Marvelous in Context: The Place of the Contes de Fées in Late Seventeenth Century France", Jack Zipes, ed., The Great Fairy Tale Tradition: From Straparola and Basile to the Brothers Grimm, p. 913.

- ^ Seifert, p. 915.

- ^ Zipes, When Dreams Came True: Classical Fairy Tales and Their Tradition, p. 47.

- ^ Maria Tatar, The Hard Facts of the Grimms' Fairy Tales, p. 19, ISBN 0-691-06722-8.

- ^ Tatar, The Hard Facts of the Grimms' Fairy Tales, p. 20.

- ^ Tatar, The Hard Facts of the Grimms' Fairy Tales, p. 32.

- ^ Byatt, pp. xlii-xliv.

- ^ Tolkien, p. 31.

- ^ K. M. Briggs, The Fairies in English Tradition and Literature, pp. 181–182, University of Chicago Press, London, 1967.

- ^ http://www.victorianweb.org/authors/dickens/pva/pva239.html

- ^ Jack Zipes, The Brothers Grimm: From Enchanted Forests to the Modern World, p. 48, ISBN 0-312-29380-1.

- ^ 68.0 68.1 Grant and Clute, "Cinema", p. 196.

- ^ Patrick Drazen, Anime Explosion!: The What? Why? & Wow! of Japanese Animation, pp. 43–44, ISBN 1-880656-72-8.

- ^ wolf, Eric James The Art of Storytelling Show Interview Jack Zipes – Are Fairy tales still useful to Children?

- ^ Zipes, When Dreams Came True: Classical Fairy Tales and Their Tradition and so on!, pp. 24–25.

- ^ Grant and Clute, "Fairytale," p. 333.

- ^ Martin, p. 41.

- ^ 74.0 74.1 Helen Pilinovsky, "Donkeyskin, Deerskin, Allerleirauh: The Reality of the Fairy Tale"

- ^ Briggs, p. 195.

- ^ Zipes, The Brothers Grimm: From Enchanted Forests to the Modern World, pp. 251–52.

- ^ D. Ward, Optimizing Bi-Modal Signal to Noise Ratios: A Fairy TalePDF (304 KiB), Defense AT&L, Sept/Oct 2005.

- ^ Diana Waggoner, The Hills of Faraway: A Guide to Fantasy, pp. 22–23, 0-689-10846-X.

- ^ Grant and Clute, "Commedia Dell'Arte", p. 219.

- ^ Grant and Clute, "Commedia Dell'Arte", p. 745.

- ^ James Graham, "Baba Yaga in Film"

- ^ Richard Scheib, Review of Labyrinth

- ^ Drazen, p. 264.

- ^ Terri Windling, "Beauty and the Beast"

- ^ Terri Windling, "The Path of Needles or Pins: Little Red Riding Hood"

- ^ Drazen, p. 38.

- ^ Spelling, Ian. Guillermo del Toro and Ivana Baquero escape from a civil war into the fairytale land of Pan's Labyrinth. Science Fiction Weekly. 2006-12-25 [2007-07-14].

- ^ Festival Highlights: 2008 Edinburgh International Film Festival. Variety. 2008-06-13 [2010-04-28].

- ^ Tolkien, p. 18.

- ^ Propp, Morphology of the Folk Tale.

- ^ Propp, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Propp, p. 74.

- ^ Propp, p. 39.

- ^ Propp, pp. 81–82.

- ^ Propp, pp. 80–81.

- ^ Christopher Vogler, The Writer's Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers, 2nd edition, p. 30, ISBN 0-941188-70-1.

- ^ Vladimir Propp's Theories

- ^ Maria Tatar, The Annotated Classic Fairy Tales, p. 43. ISBN 0-393-05163-3.

- ^ Tatar, The Hard Facts of the Grimms' Fairy Tales, p. 52.

- ^ Alan Dundes, "Interpreting Little Red Riding Hood Psychoanalytically", pp. 18–19, James M. McGlathery, ed., The Brothers Grimm and Folktale, ISBN 0-252-01549-5.

- ^ Tatar, The Hard Facts of the Grimms' Fairy Tales, p. 46.

- ^ Zipes, The Brothers Grimm: From Enchanted Forests to the Modern World, p. 48.

- ^ Marina Warner, From the Beast to the Blonde: On Fairy Tales And Their Tellers, p. 213. ISBN 0-374-15901-7.

References

[編輯]- Antti Aarne and Stith Thompson: The Types of the Folktale: A Classification and Bibliography (Helsinki, 1961)

- Thompson, Stith, The Folktale.

- Heidi Anne Heiner, "The Quest for the Earliest Fairy Tales: Searching for the Earliest Versions of European Fairy Tales with Commentary on English Translations"

- Heidi Anne Heiner, "Fairy Tale Timeline"

External links

[編輯]- Best of the Web: SurLaLune Fairy Tales - Annotated Tales including histories, Discussion Forum, Fairy Tale Books, Illustrations and Multicultural tales

- Cabinet des Fees - An Online Journal of Fairy Tale Fiction

- Children's resource for Andersen

- Children's resource for Grimm Brothers

- Endicott Studio - Journal of Mythic Arts, fairy tale history and contemporary fairy tales

- Fables - Collection and guide to fables and Fairy Tales for children

- Fairy Tale Review: A Journal of Fairy Tale Literature

- Once Upon a Time - How Fairy Tales Shape Our Lives, by Jonathan Young, Ph.D.

- Vladimir Propp's theories, and the Fairy Tale outline generator

- Perrault Fairy Tales