新鄂圖曼主義

| 系列條目 |

| 保守主義 |

|---|

|

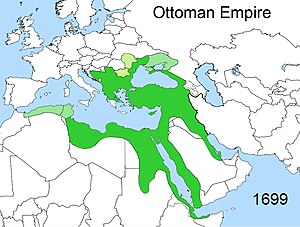

新鄂圖曼主義(土耳其語:Yeni Osmanlıcılık)是一種土耳其的帝國主義政治意識形態,目的是促進土耳其在其前身鄂圖曼帝國──一個覆蓋了整個現代土耳其領土的帝國國家──所統治過的地區之範圍內,進行更廣泛的政治參與。[註 1]

這個術語與雷傑普·塔伊普·艾爾多安對東地中海之鄰國:賽普勒斯、希臘、敘利亞、伊拉克,以及如利比亞和納戈爾諾-卡拉巴赫的統一主義、干涉主義、擴張主義之外交政策息息相關。[註 2]然而,該用語被艾爾多安政府成員所否定,例如前外交部長艾哈邁德·達夫歐魯[17]與國會議長穆斯塔法·森托普[18]。

概述[編輯]

該術語首次使用於1985年,大衛·巴查德在漆咸樓的報告[19]中,指出「新鄂圖曼主義」可能會是土耳其政府未來採納的政策之一。在土耳其入侵賽普勒斯的時候,希臘也用了類似的說法。[20]

到了21世紀時,該術語已經成為土耳其政治的國內趨勢,鄂圖曼的傳統與文化的復興,伴隨著正義與發展黨(土耳其語:Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi,簡稱AK Parti或AKP)的崛起而浮上檯面。正義與發展黨對意識形態的影響,使得鄂圖曼文化的影響力更上一層樓,同時使土耳其的世俗主義與共和政體逐漸地被動搖。[21][22]這些理想見證了正發黨外交政策即新鄂圖曼主義的復興。

現任土耳其總統雷傑普·塔伊普·艾爾多安除了把他的支持者跟世俗主義支持者(多為反對派)給區分開來,正義與發展黨所倡導的新鄂圖曼主義還成為了他們努力讓土耳其從議會制轉變成總統制之基礎。如此,他們便可建立起強大的中央集權,就跟當年的鄂圖曼時代一樣。因此,其反對者們紛紛表示艾爾多安的表現跟「鄂圖曼蘇丹」沒什麼兩樣。[23][24][25]

歷史[編輯]

新鄂圖曼主義已經被用來描述正義與發展黨領導下的土耳其外交政策,該黨在2002年在艾爾多安的領導下掌權,隨後他便成為總理。新鄂圖曼主義大幅度地翻轉了傳統的凱末爾主義之外交政策,後者強調向西方靠攏。圖爾古特·厄扎爾的諸多土耳其外交政策中,皆證實了該政策理念已經將傳統概念逐漸轉變,並為新鄂圖曼主義邁出了第一步。[26]

新鄂圖曼主義在宗教界有一定的基礎。法圖拉·居連:一位有一定影響力的伊斯蘭邪教領袖,著眼於轉變個人、社會與政治的活動,並完全接受土耳其民族主義──其定義特點是伊斯蘭教本身,而非國籍──和經濟新自由主義。同時,他強調土耳其和鄂圖曼帝國過去的連續性。[27]他對整體國家和新自由主義的強調,是因為鄂圖曼帝國晚期的領土位置與性質不斷變化的遺產總和的累積,包括巴爾幹半島上,穆斯林與基督徒間的衝突,以及後來蘇聯的擴張與威脅。[27]

鄂圖曼帝國是一個具有影響力的全球大國,在其鼎盛時期,其疆域至少涵蓋了整個巴爾幹半島與中東的大部分區域。隨著土耳其與日俱增的地區影響力驅使下,使得新鄂圖曼主義外交政策被使用在這些地區,次數逐漸增加。[28]這一決策有助於改善土耳其與鄰國的關係,特別是敘利亞、伊拉克與伊朗。然而,土耳其與曾是土耳其盟友的以色列之關係卻因此受到影響,尤其是在2008-09年的加薩戰爭[29]與2010年的加薩船隊衝突[30]之後。

然而,於2009-2014年擔任土耳其外交部長和新外交政策「首席策定師」的艾哈邁德·達夫歐魯拒絕用「新鄂圖曼主義」一詞,來描述土耳其的新外交政策。[31]

土耳其的新外交政策引發了主要在西方媒體中的一場辯論,關於土耳其是否正在經歷「軸心轉移」;換句話說,他是否正在遠離歐洲,並向中東、亞洲靠攏。[32]當土耳其跟以色列的緊張局勢升級後,此擔憂在西方媒體中更加頻繁地出現。[32]當時的總統阿卜杜拉·莒內駁斥了土耳其已經改變其外交政策軸心的說法。[33]

達夫歐魯致力於履行「與鄰國零問題」之原則來定義土耳其的外交政策,而非新鄂圖曼主義。[32]其中,「軟實力」被認為是有用的方式之一。[32]

作為新一任的總統,艾爾多安見證了鄂圖曼傳統的復興[34][35],他在新總統府使用了鄂圖曼風格的儀式來迎接巴勒斯坦總統馬哈茂德·阿巴斯,而衛兵之身著皆代表歷史上16個大突厥帝國之創開國君主的服裝。[36]在擔任土耳其總理期間,艾爾多安的正義與發展黨多次提及了有關鄂圖曼帝國的事情,比如該黨會稱支持他的民眾為「鄂圖曼帝國的子孫」(Osmanlı torunu)。[37]此舉被證明是具有爭議性的,因為這很明顯是對穆斯塔法·凱末爾創立的現代土耳其之共和性質進行公開反擊。2015年,艾爾多安曾發表聲明,他支持用鄂圖曼帝國的舊詞külliye,來代指「大學校園」,而非標準土耳其詞kampüs。[38]因此許多反對者都批評艾爾多安想要成為鄂圖曼帝國的蘇丹,並放棄共和國該有的世俗與民主。[39][40][41][42]美國哲學家諾姆·杭士基對此表示:「土耳其的艾爾多安基本上是在試圖創造像是鄂圖曼哈里發的東西,以他為哈里發國之最高領袖,同時去施壓、摧殘所剩無幾的土耳其民主。[43]」

2015年1月,當艾爾多安被提及這個問題時,他否認這些說法,並告訴TRT道,他的目標是擔任類似於英國女王伊麗莎白二世的角色,[44]並解釋:「在我看來,即使是施行君主立憲的英國,其主導仍然在女王身上。[45]」

2020年7月,在土耳其國務委員會決議取消內閣在1934年將阿亞索菲亞建立成博物館並撤銷紀念碑地位的決定後,艾爾多安下令將其重新歸類為清真寺。[46][47]他表示,根據鄂圖曼帝國和土耳其的法律,1934年的那項法律是為非法,這是因為穆罕默德二世在統治期間便授予阿亞索菲亞為瓦合甫,並指定該地點是清真寺;支持該決定的支持者認為阿亞索菲亞是蘇丹的個人財產。[48]這個重定向決定頗受爭議,並引起了反對派、聯合國教科文組織、普世教會協會、教廷與其他國家領導人的譴責。[49][50][51]2020年8月,他還簽署了將科拉教堂的管理權移交給宗教事務處的行政命令,並將其作為清真寺,開放信眾禮拜。[52] 該建築最初被鄂圖曼人改造成清真寺,後來1934年時被當時的政府指定為博物館。[53][34]

參見[編輯]

註釋[編輯]

參考來源[編輯]

- ^ Wastnidge, Edward. Imperial Grandeur and Selective Memory: Re-assessing Neo-Ottomanism in Turkish Foreign and Domestic Politics. Middle East Critique. 2019-01-02, 28 (1): 7–28. ISSN 1943-6149. S2CID 149534930. doi:10.1080/19436149.2018.1549232.

- ^ Talmiz Ahmad. Erdogan's neo-Ottomanism a risky approach for Turkey. Arab News. 27 September 2020 [13 May 2021]. (原始內容存檔於2022-01-27).

- ^ Allison Meakem. Turkey's Year of Living Dangerously. Foreign Policy. 25 December 2020 [13 May 2021]. (原始內容存檔於2022-01-27).

- ^ Joseph Croitoru. Imperialist aspirations of Turkey - Ankara on course for expansion (Original: Imperialistische Bestrebungen der Türkei - Ankara auf Expansionskurs). Die Tageszeitung: Taz (Die Tageszeitung (Taz)). 9 May 2021 [13 May 2021]. (原始內容存檔於2022-01-27).

- ^ Branislav Stanicek. Turkey: Remodelling the eastern Mediterranean (PDF). European Parliamentary Research Service. September 2020 [18 May 2021]. (原始內容存檔 (PDF)於2022-01-20).

- ^ Taşpınar, Ömer. Turkey's Strategic Vision and Syria. The Washington Quarterly. 2012-08-01, 35 (3): 127–140. ISSN 0163-660X. S2CID 154875841. doi:10.1080/0163660X.2012.706519.

- ^ Antonopoulos, Paul. Turkey's interests in the Syrian war: from neo-Ottomanism to counterinsurgency. Global Affairs. 2017-10-20, 3 (4–5): 405–419. ISSN 2334-0460. S2CID 158613563. doi:10.1080/23340460.2018.1455061.

- ^ Danforth, Nick. Turkey's New Maps Are Reclaiming the Ottoman Empire. Foreign Policy. [2020-10-08]. (原始內容存檔於2016-10-24) (美國英語).

- ^ Sahar, Sojla. Turkey's Neo-Ottomanism is knocking on the door. Modern Diplomacy. 2020-09-02 [2020-10-08]. (原始內容存檔於2020-09-02) (美國英語).

- ^ Turkey's Dangerous New Exports: Pan-Islamist, Neo-Ottoman Visions and Regional Instability. Middle East Institute. 21 April 2020 [4 May 2021]. (原始內容存檔於2020-04-22).

- ^ Sinem Cengiz. Turkey's militarized foreign policy provokes Iraq. Arab News. 7 May 2021 [9 May 2021]. (原始內容存檔於2021-05-07).

- ^ Asya Akca. Neo-Ottomanism: Turkey's foreign policy approach to Africa. Center for Strategic and International Studies. [13 May 2021]. (原始內容存檔於2019-05-30).

- ^ Michael Arizanti. Europe must wake up to Erdogan's neo-Ottoman ambition. CAPX. 10 October 2020 [13 May 2021]. (原始內容存檔於2020-10-11).

- ^ Srdja Trifkovic. Turkey as a regional power: Neo-Ottomanism in action. Politea (ReadCube). 2011, 1 (2): 83–95 [13 May 2021]. doi:10.5937/pol1102083t. (原始內容存檔於2021-05-13).

- ^ Slaviša Milačić. The revival of neo-Ottomanism in Turkey. World Geostrategic Sights. 23 October 2020 [13 May 2021]. (原始內容存檔於2020-11-01).

- ^ Hay Eytan Cohen Yanarocak. Turkish Irredentism and the Greater Middle East. Jerusalem Institute for Strategy and Security. 8 November 2021 [12 November 2021]. (原始內容存檔於2021-11-12).

- ^ Raxhimi, Altin. Davutoglu: 'I'm Not a Neo-Ottoman'. Balkan Insight. 26 April 2011 [7 January 2021]. (原始內容存檔於2022-01-27).

- ^ Rakipoglu, Zeynep. 'Turkey determined to protect its rights': Official. www.aa.com.tr. 29 January 2021 [21 June 2021]. (原始內容存檔於2022-01-27).

- ^ David Barchard. Turkey and the West. Royal Institute of International Moin Ali Khan Affairs. 1985. ISBN 0710206186.

- ^ Kemal H. Karpat, Studies on Ottoman Social and Political History: Selected Articles and Essays, BRILL, 2002, ISBN 978-90-04-12101-0, p. 524. (頁面存檔備份,存於網際網路檔案館)

- ^ İstanbul Barosu'ndan AKP'li vekile çok sert tepki. www.cumhuriyet.com.tr. [2020-10-08]. (原始內容存檔於2022-01-27) (土耳其語).

- ^ AKP'li vekil: Osmanlı'nın 90 yıllık reklam arası sona erdi. www.cumhuriyet.com.tr. [2020-10-08]. (原始內容存檔於2022-01-27) (土耳其語).

- ^ AKP'nin Osmanlı sevdası ve... - Barış Yarkadaş. [8 February 2015]. (原始內容存檔於8 February 2015).

- ^ Yeniden Osmanlı hayalinin peşinden koşan AKP, felaketi yakaladı!... www.sozcu.com.tr. [2020-10-08]. (原始內容存檔於2022-01-27) (土耳其語).

- ^ Kılıçdaroğlu: AKP çökmüş Osmanlıcılığı ambalajlıyor. T24. [2020-10-08]. (原始內容存檔於2022-01-27) (土耳其語).

- ^ Murinson, Alexander. Turkey's Entente with Israel and Azerbaijan: State Identity and Security in the Middle East and Caucasus (Routledge Studies in Middle Eastern Politics). Routledge. December 2009: 119. ISBN 978-0-415-77892-3.

- ^ 27.0 27.1 Fethullah Gülen. rlp.hds.harvard.edu. (原始內容存檔於27 March 2019).

- ^ Taspinar, Omer. Turkey's Middle East Policies: Between Neo-Ottomanism and Kemalism. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. September 2008 [5 June 2010]. (原始內容存檔於2011-01-12).

- ^ Sarah Rainsford. Turkey rallies to Gaza's plight. BBC News. 16 January 2009 [9 January 2012]. (原始內容存檔於2009-01-19).

- ^ Turkey condemns Israel over deadly attack on Gaza aid flotilla. The Telegraph (United Kingdom). 31 May 2010 [5 June 2010]. (原始內容存檔於2010-06-03).

- ^ I am not a neo-Ottoman, Davutoğlu says. Today's Zaman (Turkey). 25 November 2009 [9 January 2012]. (原始內容存檔於25 October 2013).

- ^ 32.0 32.1 32.2 32.3 Adem Palabıyık. Interpreting foreign policy correctly in the East-West perspective. Today's Zaman. 29 June 2010 [8 September 2010]. (原始內容存檔於3 July 2010).

- ^ Claims of axis shift stem from ignorance, bad intentions, says Gül. Today's Zaman. 15 June 2010 [9 January 2012]. (原始內容存檔於6 October 2012).

- ^ 34.0 34.1 Calian, Florin George. The Hagia Sophia and Turkey's Neo-Ottomanism. The Armenian Weekly. 2021-03-25 [2021-05-28]. (原始內容存檔於2021-11-05) (美國英語).

- ^ Europe must wake up to Erdogan's neo-Ottoman ambition. CapX. 2020-10-10 [2021-05-28]. (原始內容存檔於2020-10-11) (英國英語).

- ^ cumhurbaskanligi@tccb.gov.tr. T.C. CUMHURBAŞKANLIĞI : Cumhurbaşkanlığı. tccb.gov.tr. [2022-01-27]. (原始內容存檔於2011-10-04).

- ^ Oktay Özilhan. AKP'nin şarkısında 'Uzun adam' gitti 'Osmanlı torunu' geldi ! – Taraf Gazetesi. Taraf Gazetesi. (原始內容存檔於8 February 2015).

- ^ Erdoğan: Kampus değil, külliye. ilk-kursun.com. [2022-01-27]. (原始內容存檔於2016-06-03).

- ^ Recep Tayyip Erdogan: The 'new sultan' now has a new palace – and it has cost Turkish taxpayers £400m. The Independent. [2022-01-27]. (原始內容存檔於2015-09-25).

- ^ Erdogan Is Turkey's New Sultan – WSJ. WSJ. 13 August 2014 [2022-01-27]. (原始內容存檔於2022-01-27).

- ^ The next sultan?. The Economist. 16 August 2014 [2022-01-27]. (原始內容存檔於2017-10-19).

- ^ Akkoc, Raziye. 'Turkey's president is not acting like the Queen – he is acting like a sultan'. Telegraph.co.uk. 2 February 2015 [2022-01-27]. (原始內容存檔於2022-01-27).

- ^ Barsamian, David. Noam Chomsky Discusses Azeri Aggression on Artsakh. Chomsky.info. 2020-10-10 [2021-01-10]. (原始內容存檔於2021-10-21).

Erdogan in Turkey is basically trying to create something like the Ottoman Caliphate, with him as caliph, supreme leader, throwing his weight around all over the place, and destroying the remnants of democracy in Turkey at the same time, Chomsky said

- ^ Akkoc, Raziye. Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdogan: I want to be like Queen of UK. Telegraph.co.uk. 30 January 2015 [2022-01-27]. (原始內容存檔於2022-01-27).

- ^ AFP. Erdogan wants to be like Queen Elizabeth. www.timesofisrael.com. [2021-11-04]. (原始內容存檔於2021-11-06) (美國英語).

- ^ Bethan McKernan. Erdoğan leads first prayers at Hagia Sophia museum reverted to mosque. The Guardian. July 25, 2020 [2 February 2021]. (原始內容存檔於2022-01-27) (英語).

- ^ Presidential Decree on the opening of Hagia Sophia to worship promulgated on the Official Gazette. Presidency of the Republic of Turkey: Directorate of Communications. 2020-07-10 [2020-07-17]. (原始內容存檔於2022-04-05) (英語).

- ^ Turkey's Erdogan says Hagia Sophia becomes mosque after court ruling. CNBC. 2020-07-10 [2020-07-24]. (原始內容存檔於2020-07-16).

- ^ Church body wants Hagia Sophia decision reversed. BBC News. 11 July 2020 [13 July 2020]. (原始內容存檔於2022-01-29) (英語).

- ^ Pope 'pained' by Hagia Sophia mosque decision. BBC News. 12 July 2020 [13 July 2020]. (原始內容存檔於2022-02-20) (英語).

- ^ World reacts to Turkey reconverting Hagia Sophia into a mosque. Al Jazeera. 10 July 2020 [10 July 2020]. (原始內容存檔於2020-07-11) (英語).

- ^ Kariye Camii ibadete açılıyor. Sözcü. (原始內容存檔於21 August 2020). 參數

|newspaper=與模板{{cite web}}不匹配(建議改用{{cite news}}或|website=) (幫助) - ^ Yackley, Ayla. Court Ruling Converting Turkish Museum to Mosque Could Set Precedent for Hagia Sophia. The Art Newspaper. 3 December 2019 [9 December 2019]. (原始內容存檔於2021-09-17).

外部連結[編輯]

- M. Hakan Yavuz, Nostalgia for the Empire: The Politics of Neo-Ottomanism (頁面存檔備份,存於網際網路檔案館). Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2020. ISBN 9780197512289.

- Alexander Murinson, Turkish Foreign Policy in the 21st Century: Neo-Ottomanism and the Strategic Depth Doctrine. I. B. Tauris, 2020. ISBN 9781784532406

- Darko Tanasković, Neo-ottomanism: A Doctrine and Foreign Policy Practice. Association of Non-Governmental Organisations of Southeast Europe-CIVIS, 2013. ISBN 9788690810352

- Kubilay Yado Arin, The AKP's Foreign Policy, Turkey's Reorientation from the West to the East? Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Berlin, Berlin 2013. ISBN 9 783865 737199.

- Graham E. Fuller, The New Turkish Republic: Turkey as a Pivotal State in the Muslim World, United States Institute of Peace Press, 2007. ISBN 9781601270191

- Arestakes Simavoryan, Ideological Trends in the Context of Foreign Policy of Turkey (頁面存檔備份,存於網際網路檔案館). Europe & Orient, no. 11 (55-62), 2010.