酶:修订间差异

小 cewbot: 修正維基語法 102: PMID語法錯誤 |

Kaguya-Taketori(留言 | 贡献) 无编辑摘要 |

||

| 第2行: | 第2行: | ||

|G1=生命科学 |

|G1=生命科学 |

||

}} |

}} |

||

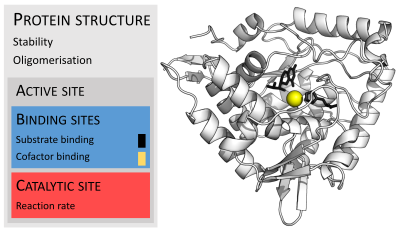

[[File:Glucosidase enzyme.png|thumb|400px|{{link-en|葡糖苷酶|Glucosidases}}能將一分子[[麥芽糖]]轉化爲兩分子[[葡萄糖]]。圖中活性位點以紅色表示,麥芽糖以黑色表示,輔酶[[NAD]]以黃色表示({{PDB|1OBB}})|alt=Ribbon diagram of glycosidase with an arrow showing the cleavage of the maltose sugar substrate into two glucose products.]] |

|||

[[File:GLO1 Homo sapiens small fast.gif|thumb|300px|人類乙二醛酶I的帶狀圖,其催化鋅離子顯示兩個紫色的球體。抑制劑,S-hexylglutathione,則表現為一個空間填充模型,填充兩個活性部位。綠色,紅色,藍色和黃色的球體,分別對應於碳,氧,氮和硫原子。]] |

|||

{{Biochemistry sidebar}} |

|||

'''酶'''(Enzymes({{IPAc-en|ˈ|ɛ|n|z|aɪ|m|z}} ))是一種[[大分子]][[生物]][[催化劑]]。酶能加快[[化學反應]]的速度,即具有[[催化作用]]。由酶催化的反應中,反應物稱爲[[底物]](substrates),生成的物質稱爲[[产物_(化学)|產物]]。幾乎所有細胞內[[新陳代謝|代謝過程]]都離不開酶。酶能大大加快這些過程中各化學反應進行的速率,使代謝過程能滿足生物體的需求<ref name = "Stryer_2002">{{cite book |vauthors=Stryer L, Berg JM, Tymoczko JL | title = Biochemistry | publisher = W.H. Freeman | location = San Francisco | year = 2002 | edition = 5th | isbn = 0-7167-4955-6 | url = http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK21154/}}{{Open access}}</ref>{{rp|8.1}}。細胞中酶的類型決定了可在該細胞中發生的[[代謝途徑]]的類型。對酶進行研究的學科稱爲「酶學」(''enzymology'')。 |

|||

[[File:Purine Nucleoside Phosphorylase.jpg|thumb|230px|[[嘌呤核苷磷酸化酶]]三维结构的飘带图示,不同的[[氨基酸]]残基用不同颜色显示]] |

|||

{{TransH}} |

|||

'''酶''',又稱'''酵素''',指具有生物[[催化]]功能的高分子物質,複合球狀蛋白質。<ref>{{en}}{{cite book|author=Smith AD ''et al.'' |title=Oxford Dictionary of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology|year=1997|publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=0-19-854768-4}}</ref>在酶的催化反应体系中,反应物分子被称为[[底物]],底物通过酶的催化转化为另一种分子。几乎所有的[[细胞]]活动进程都需要酶的参与,以提高效率。与其他非生物[[催化劑]]相似,酶藉著提供另一條[[活化能]](用''E''<sub>a</sub>或Δ''G''<sup>‡</sup>表示)需求較低的途徑来使反應進行,使更多反應粒子能擁有不少於活化能的動能,從而加快反应速率。<ref>{{cite book|author=John C. Kotz, Paul M. Treichel, John Townsend|title=Chemistry and Chemical Reactivity|year=2011|publisher=Cengage Learning|isbn=978-0840048288|pages=P.695 - 697}}</ref>大多数的酶可以将其催化的反应之速率提高上百万倍。酶作为催化剂,本身在反应过程中不被消耗,也不影响反应的[[化学平衡]]。酶有催化作用(加快反應速率),也有[[抑制剂|抑制]]作用(減慢反應速率)。<ref>{{en}}{{cite web|author=IUPAC Gold Book|title=catalyst|url=http://goldbook.iupac.org/C00876.html|publisher=IUPAC|accessdate=2014-02-26}}</ref>与其他非生物[[催化剂]]不同的是,酶具有高度的专一性,只催化特定的反应或产生特定的构型。目前已知的可以被酶催化的反应有约4000种。<ref>{{en}}{{cite journal en |url=http://www.expasy.org/NAR/enz00.pdf|author= Bairoch A.|year= 2000|title= The ENZYME database in 2000 |journal=Nucleic Acids Res|volume=28|pages=304–305|pmid=10592255 }}</ref> |

|||

Enzymes are known to catalyze more than 5,000 biochemical reaction types.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Schomburg I, Chang A, Placzek S, Söhngen C, Rother M, Lang M, Munaretto C, Ulas S, Stelzer M, Grote A, Scheer M, Schomburg D | title = BRENDA in 2013: integrated reactions, kinetic data, enzyme function data, improved disease classification: new options and contents in BRENDA | journal = Nucleic Acids Research | volume = 41 | issue = Database issue | pages = D764–72 | date = January 2013 | pmid = 23203881 | pmc = 3531171 | doi = 10.1093/nar/gks1049 }}</ref> Most enzymes are [[protein]]s, although a few are [[Ribozyme|catalytic RNA molecules]]. Enzymes' specificity comes from their unique [[tertiary structure|three-dimensional structures]]. |

|||

Like all catalysts, enzymes increase the [[reaction rate|rate of a reaction]] by lowering its [[activation energy]]. Some enzymes can make their conversion of substrate to product occur many millions of times faster. An extreme example is [[orotidine 5'-phosphate decarboxylase]], which allows a reaction that would otherwise take millions of years to occur in milliseconds.<ref name="radzicka">{{cite journal | vauthors = Radzicka A, Wolfenden R | title = A proficient enzyme | journal = Science | volume = 267 | issue = 5194 | pages = 90–931| date = January 1995 | pmid = 7809611 | doi=10.1126/science.7809611| bibcode = 1995Sci...267...90R }}</ref><ref name="pmid17889251">{{cite journal | vauthors = Callahan BP, Miller BG| title = OMP decarboxylase—An enigma persists | journal = Bioorganic Chemistry | volume = 35 | issue = 6 | pages = 465–9 | date = December 2007 | pmid = 17889251 | doi = 10.1016/j.bioorg.2007.07.004 }}</ref> Chemically, enzymes are like any catalyst and are not consumed in chemical reactions, nor do they alter the [[Chemical equilibrium|equilibrium]]of a reaction. Enzymes differ from most other catalysts by being much more specific. Enzyme activity can be affected by other molecules: [[Enzyme inhibitor|inhibitors]] are molecules that decrease enzyme activity, and [[enzyme activator|activators]] are molecules that increase activity. Many [[drug]]s and [[poison]]s are enzyme inhibitors. An enzyme's activity decreases markedly outside its optimal [[temperature]] and [[pH]]. |

|||

虽然酶大多是蛋白质,但少數具有生物催化功能的分子并非為蛋白质,有一些被称为[[核酶]]的[[核糖核酸|RNA]]分子<ref>{{en}}{{cite journal en |author=Lilley D |title=Structure, folding and mechanisms of ribozymes |journal=Curr Opin Struct Biol |volume=15 |issue=3 |pages=313-23 |year=2005 |pmid=15919196}}</ref>和一些[[脱氧核糖核酸|DNA]]分子<ref>{{cite book|author=聂剑初,吴国利等|title=生物化学简明教程|year=2007|publisher=高等教育出版社|isbn=978-7-04-007259-4|pages=93}}</ref>同样具有催化功能。此外,通过人工合成所谓[[人工酶]]也具有与酶类似的催化活性。<ref>{{en}}{{cite journal en |author=Groves JT |title=Artificial enzymes. The importance of being selective |journal=Nature |volume=389 |issue=6649 |pages=329-30 |year=1997 |pmid=9311771}}</ref>有人认为酶应定义为具有[[催化]]功能的[[生物大分子]],即生物[[催化剂]],则该定义中酶包含具有催化功能的蛋白质和[[核酶]]。<ref>{{zh}}{{cite journal|author=吴诗光,周琳|year= 2002|title=对酶概念的再认识 |journal=生物学通报|volume=04期}}</ref> |

|||

Some enzymes are used commercially, for example, in the synthesis of [[antibiotics]]. Some household products use enzymes to speed up chemical reactions: enzymes in biological[[washing powder]]s break down protein, starch or [[fat]] stains on clothes, and enzymes in [[papain|meat tenderizer]] break down proteins into smaller molecules, making the meat easier to chew. |

|||

酶的催化活性可以受其他分子影响:[[酶抑制剂|抑制剂]]是可以降低酶活性的分子;[[酶激活剂|激活剂]]则是可以增加酶活性的分子。有许多[[药物]]和[[毒物|毒药]]就是酶的抑制剂。酶的活性还可以被[[温度]]、化学环境(如[[pH值]])、底物浓度以及电磁波(如微波<ref>{{en}}{{cite journal en|author= Young DD, Nichols J, Kelly RM, Deiters A|year= 2008|title=Microwave activation of enzymatic catalysis |journal=J Am Chem Soc|volume=130|pages=10048-10049|pmid= 18613673 }}</ref>)等许多因素所影响。 |

|||

== Etymology and history == |

|||

酶在工业和人们的日常生活中的应用也非常广泛。例如,药厂用特定的合成酶来合成[[抗生素]];加酶[[洗衣粉]]通过分解蛋白质和[[脂肪]]来帮助除去衣物上的污渍和油渍。 |

|||

[[Image:Eduardbuchner.jpg|alt=Photograph of Eduard Buchner.|thumb|180px|left|[[Eduard Buchner]] ]] |

|||

By the late 17th and early 18th centuries, the digestion of [[meat]] by stomach secretions<ref name="Reaumur1752">{{cite journal | vauthors = de Réaumur RA | authorlink = René Antoine Ferchault de Réaumur | year = 1752 | title = Observations sur la digestion des oiseaux|journal = Histoire de l'academie royale des sciences | volume = 1752 | pages = 266, 461 }}</ref>and the conversion of [[starch]] to [[sugar]]s by plant extracts and [[saliva]] were known but the mechanisms by which these occurred had not been identified.<ref>{{cite book | url =http://etext.lib.virginia.edu/toc/modeng/public/Wil4Sci.html | last = Williams | first = Henry Smith | title = A History of Science: in Five Volumes''. ''Volume IV: Modern Development of the Chemical and Biological Sciences | publisher = Harper and Brothers | year = 1904 | name-list-format = vanc }}</ref> |

|||

French chemist [[Anselme Payen]] was the first to discover an enzyme, [[diastase]], in 1833.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Payen A, Persoz JF | year = 1833 | title = Mémoire sur la diastase, les principaux produits de ses réactions et leurs applications aux arts industriels | language = French | trans-title = Memoir on diastase, the principal products of its reactions, and their applications to the industrial arts | journal = Annales de chimie et de physique | series = 2nd | volume = 53 | url = https://books.google.com/?id=Q9I3AAAAMAAJ&pg=PA73 | pages = 73–92}}</ref> A few decades later, when studying the [[fermentation (food)|fermentation]] of sugar to [[alcohol]] by [[yeast]], [[Louis Pasteur]]concluded that this fermentation was caused by a [[Vitalism|vital force]] contained within the yeast cells called "ferments", which were thought to function only within living organisms. He wrote that "alcoholic fermentation is an act correlated with the life and organization of the yeast cells, not with the death or putrefaction of the cells."<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Manchester KL | title = Louis Pasteur (1822–1895)–chance and the prepared mind | journal = Trends in Biotechnology | volume = 13 | issue = 12 | pages = 511–5 |date = December 1995 | pmid = 8595136 | doi = 10.1016/S0167-7799(00)89014-9 }}</ref> |

|||

== 发现及研究史 == |

|||

[[File:Louis Pasteur, foto av Félix Nadar.jpg|thumb|left|[[法国]]科学家[[路易·巴斯德]]]] |

|||

酶的发现来源于人们对[[发酵]]机理的逐渐了解。早在18世纪末和19世纪初,人们就认识到食物在[[胃]]中被[[消化作用|消化]],<ref name="Reaumur1752">{{fr}}{{cite journal en | last = de Réaumur | first = RAF | year = 1752 | title = Observations sur la digestion des oiseaux | journal = Histoire de l'academie royale des sciences | volume = 1752|pages = 266, 461}}</ref>用植物的提取液可以将[[淀粉]]转化为[[糖]],但对于其对应的机理则并不了解。<ref>{{en}}Williams, H. S.(1904)[http://etext.lib.virginia.edu/toc/modeng/public/Wil4Sci.html A History of Science: in Five Volumes. Volume IV: Modern Development of the Chemical and Biological Sciences] Harper and Brothers (New York) Accessed 04 April 2007</ref> |

|||

In 1877, German physiologist [[Wilhelm Kühne]] (1837–1900) first used the term ''[[wiktionary:enzyme|enzyme]]'', which comes from [[Ancient Greek|Greek]] ἔνζυμον, "leavened", to describe this process.<ref>Kühne coined the word "enzyme" in: {{cite journal | vauthors = Kühne W | year = 1877 | url = https://books.google.com/?id=jzdMAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA190 |language = German | title = Über das Verhalten verschiedener organisirter und sog. ungeformter Fermente | trans-title = On the behavior of various organized and so-called unformed ferments | journal = Verhandlungen des naturhistorisch-medicinischen Vereins zu Heidelberg | series = new series | volume = 1 | issue = 3 | pages = 190–193 }} The relevant passage occurs on page 190: ''"Um Missverständnissen vorzubeugen und lästige Umschreibungen zu vermeiden schlägt Vortragender vor, die ungeformten oder nicht organisirten Fermente, deren Wirkung ohne Anwesenheit von Organismen und ausserhalb derselben erfolgen kann, als ''Enzyme'' zu bezeichnen."'' (Translation: In order to obviate misunderstandings and avoid cumbersome periphrases, [the author, a university lecturer] suggests designating as "enzymes" the unformed or not organized ferments, whose action can occur without the presence of organisms and outside of the same.)</ref> The word ''enzyme'' was used later to refer to nonliving substances such as [[pepsin]], and the word ''ferment'' was used to refer to chemical activity produced by living organisms.<ref>{{cite book | editor1-first = John L. | editor1-last = Heilbron | title = The Oxford Companion to the History of Modern Science |first1 = Frederic Lawrence | last1 = Holmes | chapter = Enzymes | page = 270 | chapterurl = https://books.google.com/books?id=abqjP-_KfzkC&pg=PA270&lpg=PA270&dq=history+of+enzymes+ferment+living+organisms&source=bl&hl=en | publisher = Oxford University Press | location = Oxford | year = 2003 | name-list-format = vanc }}</ref> |

|||

到了19世纪中叶,法国科学家[[路易·巴斯德]]对[[蔗糖]]转化为[[乙醇|酒精]]的发酵过程进行了研究,认为在[[酵母]][[细胞]]中存在一种活力物质,命名为“酵素”(ferment)。他提出发酵是这种活力物质催化的结果,并认为活力物质只存在于生命体中,细胞破裂就会失去发酵作用。<ref>{{en}}{{cite journal en |author=Dubos J.|year= 1951|title= Louis Pasteur: Free Lance of Science, Gollancz. Quoted in Manchester K. L.(1995)Louis Pasteur(1822–1895)—chance and the prepared mind.|journal= Trends Biotechnol|volume=13|issue=12|pages=511–515|id= PMID 8595136}}</ref> |

|||

[[Eduard Buchner]] submitted his first paper on the study of yeast extracts in 1897. In a series of experiments at the [[Humboldt University of Berlin|University of Berlin]], he found that sugar was fermented by yeast extracts even when there were no living yeast cells in the mixture.<ref name="urlEduard Buchner - Biographical">{{cite web | url =http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/chemistry/laureates/1907/buchner-bio.html | title = Eduard Buchner | work = Nobel Laureate Biography | publisher = Nobelprize.org | accessdate = 23 February 2015 }}</ref> He named the enzyme that brought about the fermentation of sucrose "[[zymase]]".<ref name="urlEduard Buchner - Nobel Lecture: Cell-Free Fermentation">{{cite web| url = http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/chemistry/laureates/1907/buchner-lecture.html | title = Eduard Buchner – Nobel Lecture: Cell-Free Fermentation | year = 1907 | work = Nobelprize.org | accessdate = 23 February 2015 }}</ref> In 1907, he received the [[Nobel Prize in Chemistry]] for "his discovery of cell-free fermentation". Following Buchner's example, enzymes are usually named according to the reaction they carry out: the suffix ''[[-ase]]'' is combined with the name of the [[substrate (biochemistry)|substrate]] (e.g.,[[lactase]] is the enzyme that cleaves [[lactose]]) or to the type of reaction (e.g., [[DNA polymerase]] forms DNA polymers).<ref>The naming of enzymes by adding the suffix "-ase" to the substrate on which the enzyme acts, has been traced to French scientist [[Émile Duclaux]] (1840–1904), who intended to honor the discoverers of [[diastase]] – the first enzyme to be isolated – by introducing this practice in his book {{cite book | author = Duclaux E | title = Traité de microbiologie: Diastases, toxines et venins | language = French |trans-title = Microbiology Treatise: diastases , toxins and venoms | year = 1899 | publisher = Masson and Co | location = Paris, France | url = https://books.google.com/books?id=Kp9EAAAAQAAJ&printsec=frontcover }} See Chapter 1, especially page 9.</ref> |

|||

1878年,[[德国]]生理学家[[威廉·屈内]]首次提出了'''酶'''(enzyme)这一概念。随后,'''酶'''被用于专指[[胃蛋白酶]]等一类非活体物质,而'''酵素'''(ferment)则被用于指由活体细胞产生的催化活性。 |

|||

The biochemical identity of enzymes was still unknown in the early 1900s. Many scientists observed that enzymatic activity was associated with proteins, but others (such as Nobel laureate [[Richard Willstätter]]) argued that proteins were merely carriers for the true enzymes and that proteins ''per se'' were incapable of catalysis.<ref name = "Willstätter_1927">{{cite journal| vauthors = Willstätter R | title = Faraday lecture. Problems and methods in enzyme research | journal = Journal of the Chemical Society (Resumed) |date = 1927 | pages = 1359 | doi = 10.1039/JR9270001359 }} quoted in {{cite journal | vauthors = Blow D | title = So do we understand how enzymes work? | journal = Structure (London, England : 1993) | volume = 8 | issue = 4 | pages = R77–R81 | date = April 2000 | pmid = 10801479 | doi = 10.1016/S0969-2126(00)00125-8 | url =http://cmgm3.stanford.edu/biochem/sb241/Herschlag_lectures/papers/Blow.pdf | format = pdf }}</ref> In 1926, [[James B. Sumner]] showed that the enzyme [[urease]] was a pure protein and crystallized it; he did likewise for the enzyme [[catalase]] in 1937. The conclusion that pure proteins can be enzymes was definitively demonstrated by [[John Howard Northrop]]and [[Wendell Meredith Stanley]], who worked on the digestive enzymes [[pepsin]] (1930), [[trypsin]] and [[chymotrypsin]]. These three scientists were awarded the 1946 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.<ref name="urlThe Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1946">{{cite web | url = http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/chemistry/laureates/1946/ | title = Nobel Prizes and Laureates: The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1946 | work = Nobelprize.org | accessdate = 23 February 2015 }}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Eduardbuchner.jpg|thumb|[[德国]]科学家[[爱德华·比希纳]]]] |

|||

这种对酶的错误认识很快得到纠正。1897年,德国科学家[[爱德华·比希纳]]开始对不含细胞的酵母提取液进行发酵研究,通过在[[柏林洪堡大學|柏林洪堡大学]]所做的一系列实验最终证明发酵过程并不需要完整的活细胞存在。<ref>{{en}}[http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/chemistry/laureates/1907/buchner-bio.html 诺贝尔奖获得者爱德华·比希纳的简历]Accessed 04 April 2007</ref>他将其中能够发挥发酵作用的酶命名为[[发酵酶]](zymase)。<ref>{{en}}[http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/chemistry/laureates/1907/buchner-lecture.html 爱德华·比希纳在1907年的诺贝尔奖获奖演说]Accessed 04 April 2007</ref>这一贡献打开了通向现代[[酶学]]与现代[[生物化学]]的大门,其本人也因“发现无细胞发酵及相应的生化研究”而获得了1907年的[[诺贝尔化学奖]]。在此之后,酶和酵素两个概念合二为一,并依据比希纳的命名方法,酶的发现者们根据其所催化的反应将它们命名。通常酶的英文名称是在催化底物或者反应类型的名字最后加上-ase的后缀,而对应中文命名也采用类似方法,即在名字最后加上“酶”。例如,[[乳糖酶]](lactase)是能够剪切[[乳糖]](lactose)的酶;[[DNA聚合酶]](DNA polymerase)能够催化DNA聚合反应。 |

|||

The discovery that enzymes could be crystallized eventually allowed their structures to be solved by [[x-ray crystallography]]. This was first done for [[lysozyme]], an enzyme found in tears, saliva and [[egg white]]s that digests the coating of some bacteria; the structure was solved by a group led by [[David Chilton Phillips]] and published in 1965.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Blake CC, Koenig DF, Mair GA, North AC, Phillips DC, Sarma VR | title = Structure of hen egg-white lysozyme. A three-dimensional Fourier synthesis at 2 Ångström resolution | journal = Nature | volume = 206 | issue = 4986 | pages = 757–61 | date = May 1965 | pmid = 5891407 | doi = 10.1038/206757a0 | bibcode = 1965Natur.206..757B }}</ref> This high-resolution structure of lysozyme marked the beginning of the field of [[structural biology]] and the effort to understand how enzymes work at an atomic level of detail.<ref name="pmid10390620">{{cite journal | vauthors = Johnson LN, Petsko GA | title = David Phillips and the origin of structural enzymology | journal = Trends Biochem. Sci. | volume = 24 |issue = 7 | pages = 287–9 | year = 1999 | pmid = 10390620 | doi = 10.1016/S0968-0004(99)01423-1 }}</ref> |

|||

人们在认识到酶是一类不依赖于活体细胞的物质后,下一步工作就是鉴定其生化组成成分。许多早期研究者指出,一些蛋白质与酶的催化活性相关;但包括诺贝尔奖得主[[里夏德·维尔施泰特]]在内的部分科学家认为酶不是蛋白质,他们辩称那些蛋白质只是酶分子的携带者,蛋白质本身并不具有催化活性。1926年,[[美國|美国]]生物化学家[[詹姆斯·B·萨姆纳|詹姆斯·萨姆纳]]完成了一个决定性的实验。他首次从[[刀豆屬|刀豆]]得到[[尿素酶]]结晶,并证明了尿素酶的[[蛋白质]]本质。其后,萨姆纳在1931年在[[过氧化氢酶]]的研究中再次证实了酶为蛋白质。[[约翰·霍华德·诺思罗普]]和[[温德尔·梅雷迪思·斯坦利]]通过对胃蛋白酶、[[胰蛋白酶]]和[[胰凝乳蛋白酶]]等消化性[[蛋白酶]]的研究,最终确认蛋白质可以是酶。以后陆续发现的两千余种酶均证明酶的化学本质是蛋白质。以上三位科学家因此获得1946年度诺贝尔化学奖。<ref>{{en}}[http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/chemistry/laureates/1946/ 1946年度诺贝尔化学奖获得者]Accessed 04 April 2007</ref> |

|||

== Structure == |

|||

由于蛋白质可以[[结晶]],通过[[X射线晶体学]]就可以对酶的三维结构进行研究。第一个获得结构解析的酶分子是[[溶菌酶]],一种在[[眼泪]]、[[唾液]]和[[蛋白|蛋清]]中含量丰富的酶,其功能是溶解[[细菌]]外壳。[[溶菌酶]]结构由[[大卫·菲利浦]](David Phillips)所领导的研究组解析,并于1965年发表。<ref>{{en}}{{cite journal en |author=Blake CC, Koenig DF, Mair GA, North AC, Phillips DC, Sarma VR.|year= 1965|title= Structure of hen egg-white lysozyme. A three-dimensional Fourier synthesis at 2 Angstrom resolution. |journal= Nature |volume=22|issue=206|pages=757–761|id= PMID 5891407}}</ref>这一成果的发表标志着[[结构生物学]]研究的开始,高分辨率的酶三维结构使得对于酶在分子水平上的工作机制的了解成为可能。 |

|||

{{multiple image |

|||

| direction = vertical |

|||

| width = 400 |

|||

| footer = |

|||

| image1 = Enzyme structure.svg |

|||

1980年代,[[托马斯·切赫]]和[[悉尼·奥尔特曼]]分别从[[四膜虫]]的[[核糖體RNA|rRNA]]前体的加工研究和细菌的[[核糖核酸酶P]][[蛋白质复合物|复合物]]的研究中都发现RNA本身具有自我催化作用,并提出了[[核酶]]的概念。这是第一次发现蛋白质以外的具有催化活性的生物分子。 |

|||

| alt1 = Lysozyme displayed as an opaque globular surface with a pronounced cleft which the substrate depicted as a stick diagram snuggly fits into |

|||

1989年,其二人也因此获得诺贝尔化学奖。<ref>{{en}}[http://nobelprize.org/chemistry/laureates/1989/ 1989年度诺贝尔化学奖]授予了[[托马斯·切赫]]和[[悉尼·奥尔特曼]]以奖励他们发现[[核糖核酸|RNA]]分子的催化性质。</ref> |

|||

| caption1 = Organisation of [[protein structure|enzyme structure]] and [[lysozyme]] example. Binding sites in blue, catalytic site in red and [[peptidoglycan]] substrate in black. ({{PDB|9LYZ}}) |

|||

| image2 = Q10 graph c.svg |

|||

== 生物学功能 == |

|||

| alt2 = A graph showing that reaction rate increases exponentially with temperature until denaturation causes it to decrease again. |

|||

在生物体内,酶发挥非常广泛的功能。[[訊息傳遞|信号转导]]和细胞活动的调控都离不开酶,特别是[[激酶]]和[[磷酸酶]]的参与。<ref>{{en}}{{cite journal en |author= Hunter T.|year= 1995|title= Protein kinases and phosphatases: the yin and yang of protein phosphorylation and signaling.|journal= Cell.|volume= 80 (2)|pages= 225–236|id= PMID 7834742}}</ref>酶也能产生运动,通过催化[[肌球蛋白]]上[[三磷酸腺苷|ATP]]的水解产生[[肌肉收缩]],并且能够作为[[细胞骨架]]的一部分参与运送胞内物质。<ref>{{cite journal en |url=http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pubmed&pubmedid=11294886|author= Berg JS, Powell BC, Cheney RE.|year= 2001|title= A millennial myosin census.|journal= Mol Biol Cell.|volume= 12 (4)|pages= 780–794|id= PMID 11294886}}</ref>一些位于[[细胞膜]]上的[[ATP酶]]作为[[离子泵]]参与[[主动运输]]。一些生物体中比较奇特的功能也有酶的参与,例如[[荧光素酶|-{zh:荧; zh-hans:荧; zh-hant:螢}-光素酶]]可以为[[萤火虫]]发光。<ref>{{en}}{{cite journal en |url=http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pubmed&pubmedid=2030669|author= Meighen EA.|year= 1991|title= Molecular biology of bacterial bioluminescence.|journal= Microbiol Rev.|volume= 55 (1)|pages= 123–142|id= PMID 2030669}}</ref>[[病毒]]中也含有酶,或参与侵染细胞(如[[HIV整合酶]]和[[逆转录酶]]),或参与病毒颗粒从宿主细胞的释放(如[[流行性感冒病毒|流感病毒]]的[[神经氨酸酶]])。 |

|||

| caption2 = Enzyme activity initially increases with temperature ([[Q10 (temperature coefficient)|Q10 coefficient]]) until the enzyme's structure unfolds ([[denaturation (biochemistry)|denaturation]]), leading to an optimal [[rate of reaction]] at an intermediate temperature. |

|||

}} |

|||

{{see also|Protein structure}} |

|||

酶的一个非常重要的功能是参与在动物[[消化系统]]的工作。以[[淀粉酶]]和[[蛋白酶]]为代表的一些酶可以将进入消化道的大分子([[淀粉]]和[[蛋白质]])降解为小分子,以便于肠道吸收。淀粉不能被肠道直接吸收,而酶可以将淀粉水解为[[麥芽糖|麦芽糖]]或更进一步水解为[[葡萄糖]]等肠道可以吸收的小分子。不同的酶分解不同的食物[[底物]]。在[[草食性]][[反刍亚目|反刍动物]]的消化系统中存在一些可以产生[[纤维素酶]]的细菌,纤维素酶可以分解植物[[细胞壁]]中的[[纤维素]],从而提供可被吸收的养料。<ref>{{en}}{{cite journal en |author=Mackie RI, White BA |title=Recent advances in rumen microbial ecology and metabolism: potential impact on nutrient output |journal=J. Dairy Sci. |volume=73 |issue=10 |pages=2971–95 |date=1 October 1990 |pmid=2178174 |doi=10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(90)78986-2|last2=White }}</ref> |

|||

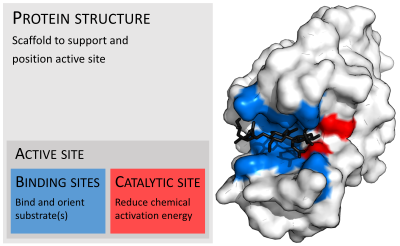

Enzymes are generally [[globular protein]]s, acting alone or in larger [[protein complex|complexes]]. Like all proteins, enzymes are linear chains of [[amino acids]] that [[protein folding|fold]] to produce a [[tertiary structure|three-dimensional structure]]. The sequence of the amino acids specifies the structure which in turn determines the catalytic activity of the enzyme.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Anfinsen CB | title = Principles that govern the folding of protein chains | journal = Science | volume = 181 | issue = 4096 |pages = 223–30 | date = July 1973 | pmid = 4124164 | doi = 10.1126/science.181.4096.223 | bibcode = 1973Sci...181..223A }}</ref> Although structure determines function, a novel enzyme's activity cannot yet be predicted from its structure alone.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Dunaway-Mariano D | title = Enzyme function discovery | journal = Structure (London, England : 1993) | volume = 16 | issue = 11 | pages = 1599–600 | date = November 2008 | pmid = 19000810 | doi = 10.1016/j.str.2008.10.001 }}</ref> Enzyme structures unfold ([[denaturation (biochemistry)|denature]]) when heated or exposed to chemical denaturants and this disruption to the structure typically causes a loss of activity.<ref>{{cite book |last1 = Petsko | first1 = Gregory A. | last2 = Ringe | first2 = Dagmar | title = Protein structure and function | date = 2003 | publisher = New Science | location = London | isbn=978-1405119221 | name-list-format = vanc | chapter = Chapter 1: From sequence to structure | chapterurl = https://books.google.com/books?id=2yRDWkHhN9QC&pg=PA27&dq=Protein+Denaturation+unfold+loss+of+function&hl=en | page = 27 }}</ref> Enzyme denaturation is normally linked to temperatures above a species' normal level; as a result, enzymes from bacteria living in volcanic environments such as [[hot spring]]s are prized by industrial users for their ability to function at high temperatures, allowing enzyme-catalysed reactions to be operated at a very high rate. |

|||

[[Image:Glycolysis (zh-cn).svg|thumb|left|480px|糖酵解酶及其在[[糖酵解]]的[[代谢途径]]的功能]] |

|||

Enzymes are usually much larger than their substrates. Sizes range from just 62 amino acid residues, for the [[monomer]] of [[4-Oxalocrotonate tautomerase|4-oxalocrotonate tautomerase]],<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Chen LH, Kenyon GL, Curtin F, Harayama S, Bembenek ME, Hajipour G, Whitman CP | title = 4-Oxalocrotonate tautomerase, an enzyme composed of 62 amino acid residues per monomer | journal = The Journal of Biological Chemistry | volume = 267 | issue = 25 | pages = 17716–21 | date = September 1992 | pmid = 1339435 }}</ref>to over 2,500 residues in the animal [[fatty acid synthase]].<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Smith S | title = The animal fatty acid synthase: one gene, one polypeptide, seven enzymes | journal = FASEB Journal | volume = 8 | issue = 15 | pages = 1248–59 | date = December 1994 | pmid = 8001737 }}</ref> Only a small portion of their structure (around 2–4 amino acids) is directly involved in catalysis: the catalytic site.<ref>{{ cite web | url = http://www.ebi.ac.uk/thornton-srv/databases/CSA/ | title = The Catalytic Site Atlas |publisher = The European Bioinformatics Institute | accessdate = 4 April 2007 }}</ref> This catalytic site is located next to one or more [[binding site]]s where residues orient the substrates. The catalytic site and binding site together comprise the enzyme's [[active site]]. The remaining majority of the enzyme structure serves to maintain the precise orientation and dynamics of the active site.<ref name = "Suzuki_2015_7">{{cite book | author = Suzuki H | title = How Enzymes Work: From Structure to Function | publisher = CRC Press| location = Boca Raton, FL | year = 2015 | isbn = 978-981-4463-92-8 | chapter = Chapter 7: Active Site Structure | pages = 117–140 }}</ref> |

|||

在[[代謝途徑|代谢途径]]中,多个酶以特定的顺序发挥功能:前一个酶的产物是后一个酶的底物;每个酶催化反应后,产物被传递到另一个酶。有些情况下,不同的酶可以平行地催化同一个反应,从而允许进行更为复杂的调控:比如一个酶可以以较低的活性持续地催化该反应,而另一个酶在被诱导后可以较高的活性进行催化。 |

|||

In some enzymes, no amino acids are directly involved in catalysis; instead, the enzyme contains sites to bind and orient catalytic [[cofactor (biochemistry)|cofactors]].<ref name="Suzuki_2015_7" /> Enzyme structures may also contain [[allosteric site]]s where the binding of a small molecule causes a [[conformational change]] that increases or decreases activity.<ref>{{cite book | author = Krauss G | title = Biochemistry of Signal Transduction and Regulation | date = 2003 | publisher = Wiley-VCH | location = Weinheim | isbn = 9783527605767 | edition = 3rd | pages = 89–114 | chapter = The Regulations of Enzyme Activity | chapterurl = https://books.google.com/books?id=iAvu2XRLnfYC&pg=PA91&dq=enzyme+metabolic+pathways+feedback+regulation&hl=en&redir_esc=y}}</ref> |

|||

酶的存在确定了整个代谢按正确的途径进行;而一旦没有酶的存在,代谢既不能按所需步骤进行,也无法以足够的速度完成合成以满足细胞的需要。实际上如果没有酶,代谢途径,如[[糖酵解]],无法独立进行。例如,葡萄糖可以直接与[[三磷酸腺苷|ATP]]反应使得其一个或多个碳原子被[[磷酸化]];在没有酶的催化时,这个反应进行得非常缓慢以致可以忽略;而一旦加入[[己糖激酶]],在6位上的碳原子的磷酸化反应获得极大加速,虽然其他碳原子的磷酸化反应也在缓慢进行,但在一段时间后检测可以发现,绝大多数产物为[[葡萄糖-6-磷酸]]。<ref>{{en}}{{cite web|url=http://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/potm/2004_2/Page1.htm|author= Jennifer McDowall|accessdate=2015-01-23|title= Enzymes of Glycolysis.}}</ref>于是每个细胞就可以通过这样一套功能性酶来完成代谢途径的整个反应网络。 |

|||

{{-}} |

|||

A small number of [[Ribonucleic acid|RNA]]-based biological catalysts called [[ribozyme]]s exist, which again can act alone or in complex with proteins. The most common of these is the [[ribosome]] which is a complex of protein and catalytic RNA components.<ref name = "Stryer_2002"/>{{rp|2.2}} |

|||

== 结构与催化机理 == |

|||

{{see also|蛋白质结构|酶促反应}} |

|||

[[File:TPI1 structure.png|thumb|300px|[[丙糖磷酸异构酶]](TIM)三维结构的飘带图和半透明的蛋白表面图显示。丙糖磷酸异构酶是典型的[[TIM桶折叠]],图中用不同颜色来表示该酶中所含有的两个TIM桶折叠[[结构域]]。]] |

|||

作为蛋白质,不同种酶之间的大小差别非常大,从62个[[氨基酸]]残基的[[4-草酰巴豆酯互变异构酶]](4-oxalocrotonate tautomerase)<ref>{{en}}{{cite journal en |author=Chen LH, Kenyon GL, Curtin F, Harayama S, Bembenek ME, Hajipour G, Whitman CP |title=4-Oxalocrotonate tautomerase, an enzyme composed of 62 amino acid residues per monomer |journal=J. Biol. Chem. |volume=267 |issue=25 |pages=17716-21 |year=1992 |pmid=1339435}}</ref>到超过2500个残基的动物[[脂肪酸合酶]]<ref>{{en}}{{cite journal en |author=Smith S |title=The animal fatty acid synthase: one gene, one polypeptide, seven enzymes |url=http://www.fasebj.org/cgi/reprint/8/15/1248 |journal=FASEB J. |volume=8 |issue=15 |pages=1248–59 |year=1994 |pmid=8001737}}</ref>。酶的[[三维结构]]决定了它们的催化活性和机理。<ref>{{en}}{{cite journal en |author=Anfinsen C.B.|year= 1973|title= Principles that Govern the Folding of Protein Chains|journal= Science|pages= 223–230|id= PMID 4124164}}</ref>大多数的酶都要比它们的催化底物大得多,并且酶分子中只有一小部分(3-4个残基)直接参与催化反应。<ref>{{en}}[http://www.ebi.ac.uk/thornton-srv/databases/CSA/ The Catalytic Site Atlas at The European Bioinformatics Institute] Accessed 04 April 2007</ref>这些参与催化残基加上参与结合底物的残基共同形成了发生催化反应的区域,这一区域就被称为“活性中心”或“[[活化位置|活性位点]]”。有许多酶含有能够结合其催化反应所必需的[[辅因子]]的结合区域。此外,还有一些酶能够结合催化反应的直接或[[代謝途徑|间接]]产物或者底物;这种结合能够增加或降低酶活,是一种[[反馈]]调节手段。 |

|||

== Mechanism == |

|||

与其他非酶蛋白相似,酶能够[[蛋白质折叠|折叠]]形成多种三维结构类型。有一部分酶是由多个[[蛋白质亚基|亚基]]所组成的复合物酶。除了[[嗜熱生物|嗜热菌]]中的酶以外,大多数酶在高温情况下会发生去折叠,其三维结构和酶活性被破坏;对于不同的酶,这种去折叠的可逆性也有所不同。 |

|||

=== |

=== Substrate binding === |

||

Enzymes must bind their substrates before they can catalyse any chemical reaction. Enzymes are usually very specific as to what [[substrate (biochemistry)|substrates]] they bind and then the chemical reaction catalysed. Specificity is achieved by binding pockets with complementary shape, charge and [[hydrophilic]]/[[hydrophobic]] characteristics to the substrates. Enzymes can therefore distinguish between very similar substrate molecules to be [[chemoselectivity|chemoselective]], [[regioselectivity|regioselective]] and[[stereospecificity|stereospecific]].<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Jaeger KE, Eggert T | title = Enantioselective biocatalysis optimized by directed evolution | journal = Current Opinion in Biotechnology | volume = 15 | issue = 4 | pages = 305–13 | date = August 2004 | pmid = 15358000 | doi = 10.1016/j.copbio.2004.06.007 }}</ref> |

|||

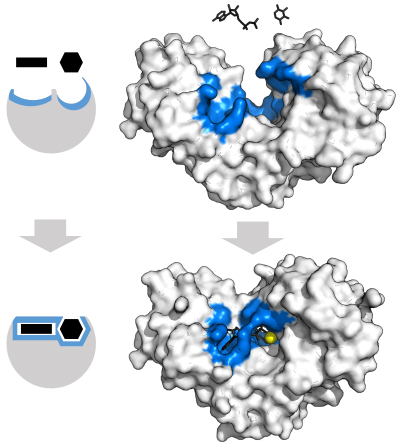

{{FileTA|Enzymatic mechanism model|png|thumb|left|300px|三种酶催化机制模式图:A. “锁-钥匙”模式;B.诱导契合模式;C.群体移动模式。}} |

|||

通常情况下,酶对于其所催化的反应类型和底物种类具有高度的专一性。酶的活性位点和底物,它们的形状、表面电荷、[[親水性|亲]][[疏水性]]都会影响专一性。酶的催化可以具有很高的[[立体专一性]]、[[区域选择性]]和[[化学选择性]](chemoselectivity |

|||

)。<ref>{{en}}{{cite journal en |author= Jaeger KE, Eggert T.|year= 2004|title= Enantioselective biocatalysis optimized by directed evolution.| journal=Curr Opin Biotechnol.|volume= 15 (4)|pages= 305–313|id= PMID 15358000}}</ref> |

|||

具体来说,酶只对具有特定空间结构的某种或某类底物起作用。例如,[[麦芽糖酶]]只能使[[葡萄糖苷键|α-葡萄糖苷键]]断裂而对[[葡萄糖苷键|β-葡萄糖苷键]]无影响。此外,酶具有对底物[[对映异构|对映异构体]]的识别能力,只能于一种[[对映异构|对映体]]作用,而对另一对映体不起作用。例如,[[胰蛋白酶]]只能水解由[[氨基酸|L-氨基酸]]形成的[[肽键]],而不能作用于[[氨基酸|D-氨基酸]]形成的肽键;[[酵母]]中的酶只能对D-构型[[糖]](如[[葡萄糖|D-葡萄糖]])发酵,而对L-构型无效。 |

|||

Some of the enzymes showing the highest specificity and accuracy are involved in the copying and [[Gene expression|expression]] of the [[genome]]. Some of these enzymes have "[[Proofreading (biology)|proof-reading]]" mechanisms. Here, an enzyme such as [[DNA polymerase]] catalyzes a reaction in a first step and then checks that the product is correct in a second step.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Shevelev IV, Hübscher U | title = The 3' 5' exonucleases | journal = Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology | volume = 3 | issue = 5 |pages = 364–76 | date = May 2002 | pmid = 11988770 | doi = 10.1038/nrm804 }}</ref> This two-step process results in average error rates of less than 1 error in 100 million reactions in high-fidelity mammalian polymerases.<ref name = "Stryer_2002"/>{{rp|5.3.1}} Similar proofreading mechanisms are also found in [[RNA polymerase]],<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Zenkin N, Yuzenkova Y, Severinov K | title = Transcript-assisted transcriptional proofreading | journal = Science | volume = 313 | issue = 5786 | pages = 518–20 | date = July 2006 |pmid = 16873663 | doi = 10.1126/science.1127422 | bibcode = 2006Sci...313..518Z }}</ref> [[aminoacyl tRNA synthetase]]s<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Ibba M, Soll D | title = Aminoacyl-tRNA synthesis | journal = Annual Review of Biochemistry | volume = 69 | pages = 617–50 | pmid = 10966471 | doi = 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.617 | year=2000}}</ref> and[[ribosome]]s.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Rodnina MV, Wintermeyer W | title = Fidelity of aminoacyl-tRNA selection on the ribosome: kinetic and structural mechanisms | journal = Annual Review of Biochemistry | volume = 70 | pages = 415–35 | pmid = 11395413 | doi = 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.415 | year=2001}}</ref> |

|||

Conversely, some enzymes display [[enzyme promiscuity]], having broad specificity and acting on a range of different physiologically relevant substrates. Many enzymes possess small side activities which arose fortuitously (i.e. [[Neutral evolution|neutrally]]), which may be the starting point for the evolutionary selection of a new function.<ref name=Tawfik10>{{cite journal | vauthors = Khersonsky O, Tawfik DS | title = Enzyme promiscuity: a mechanistic and evolutionary perspective | journal = Annual Review of Biochemistry | volume = 79 |pages = 471–505 | pmid = 20235827 | pmc = | doi = 10.1146/annurev-biochem-030409-143718 | year=2010}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = O'Brien PJ, Herschlag D | title = Catalytic promiscuity and the evolution of new enzymatic activities | journal = Chemistry & Biology | volume = 6 | issue = 4 | pages = R91–R105 | date = April 1999 | pmid = 10099128| doi = 10.1016/S1074-5521(99)80033-7 }}</ref> |

|||

为了解释酶的专一性,研究者提出了多种可能的酶与底物的结合模式(后两种模式为大多数研究者所倾向): |

|||

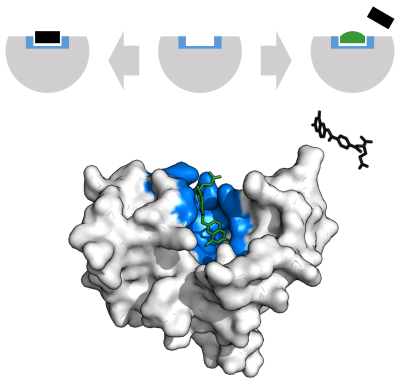

[[File:Hexokinase induced fit.svg|alt=Hexokinase displayed as an opaque surface with a pronounced open binding cleft next to unbound substrate (top) and the same enzyme with more closed cleft that surrounds the bound substrate (bottom)|thumb|400px|Enzyme changes shape by induced fit upon substrate binding to form enzyme-substrate complex. [[Hexokinase]] has a large induced fit motion that closes over the substrates [[adenosine triphosphate]] and [[xylose]]. Binding sites in blue, substrates in black and [[magnesium|Mg<sup>2+</sup>]]cofactor in yellow. ({{PDB|2E2N}}, {{PDB2|2E2Q}})]] |

|||

==== “锁-钥”模式 ==== |

|||

“锁-钥”模式(“Lock and key”,也稱為'''鎖鑰假說''')由[[赫尔曼·埃米尔·费歇尔]]于1894年提出,基于的理论是酶和底物都有一定的外形,当且仅当两者之间的外形能够精确互补时,催化反应才可以发生。<ref>{{de}}{{cite journal en |author= Fischer E.|year= 1894|title= Einfluss der Configuration auf die Wirkung der Enzyme| journal=Ber. Dt. |

|||

Chem. Ges.|volume=27|pages=2985–2993|url = http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k90736r/f364.chemindefer }}</ref>这一模式通常被形象地称为“锁-钥匙”模式。虽然这一模式能够解释酶的专一性,但却无法说明为什么酶能够稳定反应的过渡态。 |

|||

==== |

==== "Lock and key" model ==== |

||

To explain the observed specificity of enzymes, in 1894 [[Hermann Emil Fischer|Emil Fischer]] proposed that both the enzyme and the substrate possess specific complementary geometric shapes that fit exactly into one another.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Fischer E | year = 1894 | title = Einfluss der Configuration auf die Wirkung der Enzyme | language = German |trans_title = Influence of configuration on the action of enzymes | journal=Berichte der Deutschen chemischen Gesellschaft zu Berlin | volume = 27 | issue = 3 | pages = 2985–93 | url = http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k90736r/f364.chemindefer|doi=10.1002/cber.18940270364 }} From page 2992: ''"Um ein Bild zu gebrauchen, will ich sagen, dass Enzym und Glucosid wie Schloss und Schlüssel zu einander passen müssen, um eine chemische Wirkung auf einander ausüben zu können."'' (To use an image, I will say that an enzyme and a glucoside [i.e., glucose derivative] must fit like a lock and key, in order to be able to exert a chemical effect on each other.)</ref> This is often referred to as "the lock and key" model.<ref name="Stryer_2002" />{{rp|8.3.2}} This early model explains enzyme specificity, but fails to explain the stabilization of the transition state that enzymes achieve.<ref name="Cooper_2000">{{cite book |author = Cooper GM | title = The Cell: a Molecular Approach | date = 2000 | publisher = ASM Press | location = Washington (DC ) | isbn = 0-87893-106-6| edition = 2nd | chapter = Chapter 2.2: The Central Role of Enzymes as Biological Catalysts | chapterurl = http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK9921/}}</ref> |

|||

{{FileTA|Induced fit diagram|svg|thumb|400px|诱导契合模式详解图}} |

|||

==== Induced fit model ==== |

|||

诱导契合模式(Induced fit)由[[丹尼尔·科什兰]](Daniel Koshland)通过修改“锁-钥”模式,于1958年提出。基于的理论是,既然酶作为蛋白质,其结构是具有一定柔性的,因此活性位点在结合底物的过程中,通过与底物分子之间的相互作用,可以不断发生微小的形变。<ref>{{en}}{{cite journal en |url=http://www.pnas.org/cgi/reprint/44/2/98|author=Koshland D. E.|year= 1958|title= Application of a Theory of Enzyme Specificity to Protein Synthesis|journal=Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.|volume=44|issue=2|pages=98–104|id= PMID 16590179}}</ref>在这一模式中,底物不是简单地结合到刚性的活性位点上,活性位点上的氨基酸残基的[[侧链]]可以摆动到正确的位置,使得酶能够进行催化反应。在结合过程中,活性位点不断地发生变化,直到底物完全结合,此时活性位点的形状和带电情况才会最终确定下来。<ref>{{en}}{{cite book en |last=Boyer |first=Rodney |title=Concepts in Biochemistry |origyear=2002 |accessdate=2007-04-21 |edition=2nd ed.|publisher=John Wiley & Sons, Inc. |location=New York, Chichester, Weinheim, Brisbane, Singapore, Toronto. |language=English |isbn=0-470-00379-0 |pages=137–138 |chapter=6}}</ref>在一些情况下,底物在进入活性中心时也是会发生微小形变的,如[[糖苷水解酶|糖苷酶]]的催化反应。<ref>{{en}}{{cite journal|author=Vasella A, Davies GJ, Bohm M.|year= 2002|title= Glycosidase mechanisms.|journal=Curr Opin Chem Biol.|volume=6|issue=5|pages=619–629|id= PMID 12413546}}</ref> |

|||

In 1958, [[Daniel E. Koshland, Jr.|Daniel Koshland]] suggested a modification to the lock and key model: since enzymes are rather flexible structures, the active site is continuously reshaped by interactions with the substrate as the substrate interacts with the enzyme.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Koshland DE | title = Application of a Theory of Enzyme Specificity to Protein Synthesis | journal = Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America | volume = 44 | issue = 2 | pages = 98–104 | date = February 1958 | pmid = 16590179 | pmc = 335371 | doi = 10.1073/pnas.44.2.98 | bibcode = 1958PNAS...44...98K }}</ref> As a result, the substrate does not simply bind to a rigid active site; the amino acid [[Side chain|side-chains]] that make up the active site are molded into the precise positions that enable the enzyme to perform its catalytic function. In some cases, such as [[glycosidases]], the substrate [[molecule]] also changes shape slightly as it enters the active site.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Vasella A, Davies GJ, Böhm M |title = Glycosidase mechanisms | journal = Current Opinion in Chemical Biology | volume = 6 | issue = 5 | pages = 619–29 | date = October 2002 | pmid = 12413546 | doi = 10.1016/S1367-5931(02)00380-0 }}</ref> The active site continues to change until the substrate is completely bound, at which point the final shape and charge distribution is determined.<ref>{{cite book | last = Boyer | first = Rodney | title = Concepts in Biochemistry | edition = 2nd | publisher = John Wiley & Sons, Inc. | location = New York, Chichester, Weinheim, Brisbane, Singapore, Toronto. | isbn = 0-470-00379-0 | pages=137–8 | chapter = Chapter 6: Enzymes I, Reactions, Kinetics, and Inhibition | year = 2002 | oclc = 51720783 |name-list-format = vanc}}</ref> |

|||

Induced fit may enhance the fidelity of molecular recognition in the presence of competition and noise via the [[conformational proofreading]] mechanism.<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors = Savir Y, Tlusty T | title = Conformational proofreading: the impact of conformational changes on the specificity of molecular recognition | journal = PLoS ONE | volume = 2| issue = 5 | pages = e468 | year = 2007 | pmid = 17520027 | pmc = 1868595 | doi = 10.1371/journal.pone.0000468 | url = http://www.weizmann.ac.il/complex/tlusty/papers/PLoSONE2007.pdf| editor1-last = Scalas | editor1-first = Enrico |name-list-format=vanc| bibcode = 2007PLoSO...2..468S }}</ref> |

|||

=== Catalysis === |

|||

群体移动模式(Population shift)是近年来提出的一种新的酶与底物的结合模式,<ref>{{en}}{{cite journal en |author=Kumar S, Ma B, Tsai CJ, Sinha N, Nussinov R.|year= 2000|title= Folding and binding cascades: dynamic landscapes and population shifts|journal=Protein Sci.|volume=9|issue=1|pages=10–19|id= PMID 10739242}}</ref>试图解释在一些酶中所发现的底物结合前后,酶的构象有较大变化,而这是用诱导契合模式无法解释的。其基于的假设是,酶在溶液中同时存在不同构象,一种构象(构象A)为适合底物结合的构象,而另一种(构象B)则不适合,这两种构象之间保持着动态平衡。在没有底物存在的情况下,构象B占主导地位;当加入底物后,随着底物不断与构象A结合,溶液中构象A含量下降,两种构象之间的平衡被打破,导致构象B不断地转化为构象A。 |

|||

{{See also|Enzyme catalysis}} |

|||

=== 机理 === |

|||

酶催化机理多种多样,殊途同归的是最终都能够降低反应的ΔG<sup>‡</sup>:<ref>{{en}}Fersht, A (1985) ''Enzyme Structure and Mechanism''(2nd ed)p50–52 W H Freeman & co, New York ISBN 978-0-7167-1615-0</ref> |

|||

* 创造稳定[[过渡态]]的[[微环境]]。例如,通过与反应的过渡态分子更高的亲和力(与底物分子相比),提高其稳定性;或扭曲底物分子,以使得底物更趋向于转化为过渡态。 |

|||

* 提供不同的反应途径。例如,暂时性地激活底物,形成酶-底物复合物的中间态。 |

|||

* 将反应中不同底物分子结合到一起,并固定其方位至反应能够正确发生的位置,从而降低反应的“门槛”。如果只考虑反应的[[焓]]变(ΔH<sup>‡</sup>),则此作用会被忽略。有趣的是,这一作用同时也会降低反应基态的稳定性,<ref>{{en}}Jencks W.P. "Catalysis in Chemistry and Enzymology." 1987, Dover, New York</ref>因此对于催化的贡献较小。<ref>{{en}}{{cite journal en |author=Villa J, Strajbl M, Glennon TM, Sham YY, Chu ZT, Warshel A |title=How important are entropic contributions to enzyme catalysis? |journal=Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. |volume=97 |issue=22 |pages=11899-904 |year=2000 |pmid=11050223 |url=http://www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/97/22/11899}}</ref> |

|||

Enzymes can accelerate reactions in several ways, all of which lower the [[activation energy]] (ΔG<sup>‡</sup>, [[Gibbs free energy]])<ref name="Fersht_1985">{{cite book | author = Fersht A | title = Enzyme Structure and Mechanism | publisher = W.H. Freeman | location = San Francisco | year = 1985 | pages = 50–2 | isbn = 0-7167-1615-1}}</ref> |

|||

==== 过渡态的稳定 ==== |

|||

# By stabilizing the transition state: |

|||

对比同一反应在不受催化和受酶催化的情况,可以了解酶是如何稳定过渡态的。最有效的稳定方式是电荷相互作用,酶可以为过渡态分子上的电荷提供固定的相反电荷,<ref>{{en}}{{cite journal en |author=Warshel A, Sharma PK, Kato M, Xiang Y, Liu H, Olsson MH |title=Electrostatic basis for enzyme catalysis |journal=Chem. Rev. |volume=106 |issue=8 |pages=3210-35 |year=2006 |pmid=16895325}}</ref>而这是在水溶液非催化反应体系中不存在的。 |

|||

#* Creating an environment with a charge distribution complementary to that of the transition state to lower its energy.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Warshel A, Sharma PK, Kato M, Xiang Y, Liu H, Olsson MH | title = Electrostatic basis for enzyme catalysis | journal = Chemical Reviews | volume = 106 | issue = 8 | pages = 3210–35 | date = August 2006 | pmid = 16895325 | doi = 10.1021/cr0503106 }}</ref> |

|||

# By providing an alternative reaction pathway: |

|||

#* Temporarily reacting with the substrate, forming a covalent intermediate to provide a lower energy transition state.<ref>{{cite book | last1 = Cox | first1 = Michael M. | last2 = Nelson | first2 = David L. | title = Lehninger Principles of Biochemistry | date = 2013 | publisher = W.H. Freeman | location = New York, N.Y. | isbn = 978-1464109621 | edition = 6th| chapter = Chapter 6.2: How enzymes work | page = 195 | chapterurl = http://www.amazon.co.uk/Lehninger-Principles-Biochemistry-David-Nelson/dp/1464109621/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1425406097&sr=1-1&keywords=9781464109621 | name-list-format = vanc }}</ref> |

|||

# By destabilising the substrate ground state: |

|||

#* Distorting bound substrate(s) into their transition state form to reduce the energy required to reach the transition state.<ref name=PMID12947189>{{cite journal | vauthors = Benkovic SJ, Hammes-Schiffer S | title = A perspective on enzyme catalysis | journal = Science | volume = 301 | issue = 5637 | pages = 1196–202 | date = August 2003 | pmid = 12947189| doi = 10.1126/science.1085515 | bibcode = 2003Sci...301.1196B }}</ref> |

|||

#* By orienting the substrates into a productive arrangement to reduce the reaction [[entropy]] change.<ref>{{cite book | author = Jencks WP | title = Catalysis in Chemistry and Enzymology | publisher = Dover | location = Mineola, N.Y | year = 1987 | isbn = 0-486-65460-5 }}</ref> The contribution of this mechanism to catalysis is relatively small.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Villa J, Strajbl M, Glennon TM, Sham YY, Chu ZT, Warshel A | title = How important are entropic contributions to enzyme catalysis? | journal = Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America | volume = 97 | issue = 22 | pages = 11899–904 | date = October 2000 | pmid = 11050223 | pmc = 17266 | doi = 10.1073/pnas.97.22.11899 | bibcode = 2000PNAS...9711899V }}</ref> |

|||

Enzymes may use several of these mechanisms simultaneously. For example, [[protease]]s such as [[trypsin]] perform covalent catalysis using a [[catalytic triad]], stabilise charge build-up on the transition states using an [[oxyanion hole]], complete [[hydrolysis]] using an oriented water substrate. |

|||

=== Dynamics === |

|||

最近的一些研究揭示了酶内部的动态作用与其催化机制之间的联系。<ref>{{en}}{{cite journal en |author=Eisenmesser EZ, Bosco DA, Akke M, Kern D. |title=Enzyme dynamics during catalysis |journal=Science |volume=295 |issue=5559|pages=1520–3 |year=2002 |pmid=11859194}}</ref><ref>{{en}}{{cite journal en |author=Agarwal PK. |title=Role of protein dynamics in reaction rate enhancement by enzymes |journal=J. Am. Chem. Soc. |volume=127 |issue=43 |pages=15248-56 |year=2005 |pmid=16248667}}</ref>酶内部的动态作用可以描述为其内部组成元件(小的如一个氨基酸、一组氨基酸;大的如一段环区域、一个[[α螺旋]]或相邻的[[β折叠|β链]];或者可以是整个[[结构域]])的运动,这种运动可以发生在从[[飞秒]](10<sup>−15</sup>秒)到秒的不同时间尺度。通过这种动态作用,整个酶分子结构中的氨基酸残基就都可以对酶催化作用施加影响。<ref>{{en}}{{cite journal en |url=http://www.structure.org/content/article/abstract?uid=PIIS096921260500167X|author=Yang LW, Bahar I.|title=Coupling between catalytic site and collective dynamics: A requirement for mechanochemical activity of enzymes.| journal=Structure.|volume=13|pages=893–904|id=PMID 15939021|date=June 5, 2005}}</ref><ref>{{en}}{{cite journal en |url=http://www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/99/5/2794|author=Agarwal PK, Billeter SR, Rajagopalan PT, Benkovic SJ, Hammes-Schiffer S.|title=Network of coupled promoting motions in enzyme catalysis.| journal=Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A.|volume=99|pages=2794–9|id=PMID 11867722|date=March 5, 2002}}</ref><ref>{{en}}Agarwal PK, Geist A, Gorin A. ''Protein dynamics and enzymatic catalysis: investigating the peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerization activity of cyclophilin A.'' Biochemistry. 2004 August 24;43 (33):10605-18. PMID 15311922</ref><ref>{{en}}{{cite journal en |url=http://www.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=ArticleURL&_udi=B6VRP-4D4JYMC-6&_coverDate=08%2F31%2F2004&_alid=465962916&_rdoc=1&_fmt=&_orig=search&_qd=1&_cdi=6240&_sort=d&view=c&_acct=C000050221&_version=1&_urlVersion=0&_userid=10&md5=613585a6164baa38b4f6536d8da9170a|author=Tousignant A, Pelletier JN.|title=Protein motions promote catalysis.|journal=Chem Biol.|volume=11|issue=8|pages=1037–42|id=PMID 15324804|date=Aug 2004}}</ref>蛋白质动态作用在许多酶中都起到关键作用,而是小的快速运动还是大的相对较慢的运动起作用更多是依赖于酶所催化的反应类型。对于动态作用的这些新发现,对于了解[[别构调节|别构作用]]、设计人工酶和开发新药都有重要意义。 |

|||

{{See also|Protein dynamics}} |

|||

但必须指出的是,这种时间依赖的动态进程不大可能帮助提高酶催化反应的速率,因为这种运动是随机发生的,并且速率常数取决于到达中间态的几率(P,P = exp {ΔG<sup>‡</sup>/RT})。<ref>{{en}} Olsson M.H.M., Parson W.W. and Warshel A. "Dynamical Contributions to Enzyme Catalysis: Critical Tests of A Popular Hypothesis" Chem. Rev., 2006 105: 1737-1756</ref>而且,降低ΔG<sup>‡</sup>需要相对较小的运动(与在溶液反应中的相应运动相比)以达到反应物与产物之间的过渡态。因此,这种运动或者说动态作用对于催化反应有何贡献还不清楚。 |

|||

Enzymes are not rigid, static structures; instead they have complex internal dynamic motions – that is, movements of parts of the enzyme's structure such as individual amino acid residues, groups of residues forming a [[turn (biochemistry)|protein loop]] or unit of [[protein secondary structure|secondary structure]], or even an entire [[protein domain]]. These motions give rise to a [[conformational ensemble]] of slightly different structures that interconvert with one another at [[thermodynamic equilibrium|equilibrium]]. Different states within this ensemble may be associated with different aspects of an enzyme's function. For example, different conformations of the enzyme [[dihydrofolate reductase]] are associated with the substrate binding, catalysis, cofactor release, and product release steps of the catalytic cycle.<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Ramanathan A, Savol A, Burger V, Chennubhotla CS, Agarwal PK |title=Protein conformational populations and functionally relevant substates |journal=Acc. Chem. Res. |volume=47 |issue=1 |pages=149–56 |year=2014|pmid=23988159 |doi=10.1021/ar400084s |url=}}</ref> |

|||

=== 别构调节 === |

|||

{{main|别构调节}} |

|||

在结合[[效应子]]的情况下,别构酶能够改变自身结构,从而达到调节酶活性的效应。这种调节作用可以是直接的,即效应子结合到别构酶上;也可以是间接的,即效应子通过结合其它能够与别构酶相互作用的蛋白来发挥调节作用。<ref>{{Cite book|author=Laurence A. Moran, Robert Horton, Gray Scrimgeour & Marc D. Perry|year=2011|title=Principles of Biochemistry (Fifth Edition)|trans_title=生物化学原理|publisher=[[培生出版集團]]|pages= 153-154|chapter= Properties of Enzymes|isbn=0-321-70733-8}}</ref> |

|||

=== |

=== Allosteric modulation === |

||

{{main |Allosteric regulation}} |

|||

一般情况下,酶在常温、常压和中性水溶液条件下可以正常发挥催化活性。在极端条件下,包括高温、过高或过低[[pH值|pH]]条件等,酶会失去催化活性,这被称为酶的失活。但也有一些酶则偏好在非常条件下发挥催化功能,如[[嗜熱生物|嗜热菌]]中的酶在高温条件下反而具有较高活性,[[嗜酸菌]]中的酶又偏好低pH条件。 |

|||

Allosteric sites are pockets on the enzyme, distinct from the active site, that bind to molecules in the cellular environment. These molecules then cause a change in the conformation or dynamics of the enzyme that is transduced to the active site and thus affects the reaction rate of the enzyme.<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Tsai CJ, Del Sol A, Nussinov R|title=Protein allostery, signal transmission and dynamics: a classification scheme of allosteric mechanisms |journal=Mol Biosyst |volume=5 |issue=3 |pages=207–16 |year=2009|pmid=19225609 |pmc=2898650 |doi=10.1039/b819720b |url=}}</ref> In this way, allosteric interactions can either inhibit or activate enzymes. Allosteric interactions with metabolites upstream or downstream in an enzyme's metabolic pathway cause [[feedback]] regulation, altering the activity of the enzyme according to the [[Flux (metabolism)|flux]] through the rest of the pathway.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Changeux JP, Edelstein SJ | title = Allosteric mechanisms of signal transduction | journal = Science | volume = 308 | issue = 5727 |pages = 1424–8 | date = June 2005 | pmid = 15933191 | doi = 10.1126/science.1108595 | bibcode = 2005Sci...308.1424C }}</ref> |

|||

== 辅因子与辅酶 == |

|||

{{main|辅酶|辅因子}} |

|||

=== 辅因子 === |

|||

==Cofactors== |

|||

并非所有的酶自身就可以催化反应,有一些酶需要结合一些非蛋白小分子后才可以发挥或提高催化活性。<ref name="cofactor">{{en}}{{cite web|url=http://academic.brooklyn.cuny.edu/biology/bio4fv/page/coenzy_.htm |title=coenzymes and cofactors |accessdate=2008-01-13}}</ref>这些小分子被称为辅因子,它们既可以是无机分子或[[离子]](如金属离子、[[铁硫簇]]),也可以是有机化合物(如[[黄素]]、[[血紅素|血红素]])。有机辅因子通常是[[辅基]],可以与其对应的酶非常牢固地结合。这种牢固结合的辅因子与辅酶(如[[烟酰胺腺嘌呤二核苷酸]])不同的是,在整个催化反应过程中,它们一直结合在酶活性位点上而不脱落。 |

|||

[[File:Transketolase + TPP.png|thumb|400px|alt=Thiamine pyrophosphate displayed as an opaque globular surface with an open binding cleft where the substrate and cofactor both depicted as stick diagrams fit into.|Chemical structure for [[thiamine pyrophosphate]] and protein structure of [[transketolase]]. Thiamine pyrophosphate cofactor in yellow and [[xylulose 5-phosphate]] substrate in black. ({{PDB|4KXV}})]] |

|||

以含有辅因子的[[碳酸酐酶]]为例:其辅因子锌牢固地结合在活性中心,参与催化反应。<ref>{{en}}{{cite journal en |author= Fisher Z, Hernandez Prada JA, Tu C, Duda D, Yoshioka C, An H, Govindasamy L, Silverman DN and McKenna R.|year= 2005|title= Structural and kinetic characterization of active-site histidine as a proton shuttle in catalysis by human carbonic anhydrase II.| journal=Biochemistry.|volume= 44 (4)|pages= 1097-115|id= PMID 15667203}}</ref>黄素或血红素等辅因子可以参与催化[[氧化还原反应]],往往结合于催化此类反应的酶中。 |

|||

{{main|Cofactor (biochemistry)}} |

|||

需要辅因子结合以进行催化的酶,在不结合辅因子的情况下,被称为'''酶元'''(apoenzyme);而在结合了辅因子后,被称为'''全酶'''(holoenzyme)。大多数全酶中,辅因子都是以非[[共价键|共价]]连接方式与酶结合;也有一些有机辅因子可以与酶共价结合(如[[丙酮酸脱氢酶]]中的[[焦磷酸硫胺素]])。 |

|||

Some enzymes do not need additional components to show full activity. Others require non-protein molecules called cofactors to be bound for activity.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.chem.qmul.ac.uk/iupac/bioinorg/CD.html#34 | title = Glossary of Terms Used in Bioinorganic Chemistry: Cofactor | accessdate = 30 October 2007 | last = de Bolster |first = M.W.G. | year = 1997 | publisher = International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry | name-list-format = vanc }}</ref> Cofactors can be either [[inorganic]] (e.g.,[[ion|metal ions]] and [[iron-sulfur cluster]]s) or [[organic molecules|organic compounds]] (e.g., [[flavin group|flavin]] and [[heme]]). Organic cofactors can be either[[coenzyme]]s, which are released from the enzyme's active site during the reaction, or [[prosthetic groups]], which are tightly bound to an enzyme. Organic prosthetic groups can be covalently bound (e.g., [[biotin]] in enzymes such as [[pyruvate carboxylase]]).<ref name="pmid10470036">{{cite journal | vauthors = Chapman-Smith A, Cronan JE | title = The enzymatic biotinylation of proteins: a post-translational modification of exceptional specificity | journal = Trends Biochem. Sci. | volume = 24 | issue = 9 | pages = 359–63 | year = 1999 | pmid = 10470036 | doi = 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01438-3}}</ref> |

|||

=== 辅酶 === |

|||

[[File:NADH-3D-vdW.png|thumb|left|150px|辅酶[[烟酰胺腺嘌呤二核苷酸]]的空间填充式结构模型]] |

|||

辅酶是一类可以将化学基团从一个酶转移到另一个酶上的有机小分子,与酶较为松散地结合,对于特定酶的活性发挥是必要的。<ref name="cofactor"/>有许多[[维生素|维他命]]及其衍生物,如[[核黄素]]、[[硫胺|硫胺素]]和[[叶酸]],都属于辅酶。<ref>{{en}}{{cite web |url=http://www.elmhurst.edu/~chm/vchembook/571cofactor.html |title=Enzyme Cofactors |accessdate=2008-01-13}}</ref>这些化合物无法由人体合成,必须通过饮食补充。不同的辅酶能够携带的化学基团也不同:[[烟酰胺腺嘌呤二核苷酸]]或NADP<sup>+</sup>携带氢离子,[[辅酶A]]携带乙酰基,叶酸携带甲酰基,[[S-腺苷基蛋氨酸]]也可携带甲基。<ref>{{en}}AF Wagner, KA Folkers (1975) ''Vitamins and coenzymes.'' Interscience Publishers New York| ISBN 978-0-88275-258-7</ref> |

|||

An example of an enzyme that contains a cofactor is [[carbonic anhydrase]], which is shown in the [[ribbon diagram]] above with a zinc cofactor bound as part of its active site.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Fisher Z, Hernandez Prada JA, Tu C, Duda D, Yoshioka C, An H, Govindasamy L, Silverman DN, McKenna R | title = Structural and kinetic characterization of active-site histidine as a proton shuttle in catalysis by human carbonic anhydrase II | journal = Biochemistry | volume = 44 | issue = 4 | pages = 1097–115 | date = February 2005 |pmid = 15667203 | doi = 10.1021/bi0480279 }}</ref> These tightly bound ions or molecules are usually found in the active site and are involved in catalysis.<ref name = "Stryer_2002"/>{{rp|8.1.1}} For example, flavin and heme cofactors are often involved in [[redox]] reactions.<ref name = "Stryer_2002"/>{{rp|17}} |

|||

由于辅酶在酶催化反应中其化学组分发生了变化,因此可以认为辅酶是一种特殊的底物或者称为“第二底物”。这种所谓的第二底物可以被许多酶所利用。例如,目前已知有约七百种酶可以利用辅酶[[烟酰胺腺嘌呤二核苷酸]]进行催化。<ref>{{en}}[http://www.brenda.uni-koeln.de/ BRENDA The Comprehensive Enzyme Information System] Accessed 04 April 2007</ref> |

|||

Enzymes that require a cofactor but do not have one bound are called ''apoenzymes'' or ''apoproteins''. An enzyme together with the cofactor(s) required for activity is called a''holoenzyme'' (or haloenzyme). The term ''holoenzyme'' can also be applied to enzymes that contain multiple protein subunits, such as the [[DNA polymerase]]s; here the holoenzyme is the complete complex containing all the subunits needed for activity.<ref name = "Stryer_2002"/>{{rp|8.1.1}} |

|||

在细胞内,反应后的辅酶可以被再生,以维持其胞内浓度在一个稳定的水平上。例如,[[NADPH]]可以通过[[磷酸戊糖途径]]再生,[[S-腺苷基蛋氨酸]]則可以通过[[甲硫氨酸腺苷基转移酶]]来再生。由于辅酶的再生对于维持酶反应体系的稳定是必要的,因此,辅酶再生系统获得了大量的实验室以及工业应用。<ref>{{zh}}{{cite journal |author=张小里,岑沛霖 |title=伴有辅酶再生的多酶反应技术进展 |journal=化工进展 |volume=6 |pages=50-52, 59 |year=1996 }}</ref> |

|||

== |

===Coenzymes=== |

||

{{see also|活化能|热力学平衡|化学平衡}} |

|||

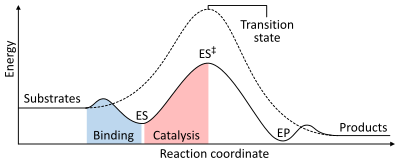

{{FileTA|Activation Energy|png|thumb|300px|有酶或无酶催化反应体系中反应进程与能量关系图示。可以看出,当反应没有酶的催化时,底物通常需要获得较高的活化能才能到达过渡态,然后才能生成产物;而当反应体系中有酶催化时,通过酶对过渡态的稳定作用,降低了达到过渡态所需能量,从而降低了整个反应所需的能量。}} |

|||

与其他催化剂一样,酶并不改变反应的[[平衡常数]],而是通过降低反应的[[活化能]]来加快反应速率(见右图)。通常情况下,反应在酶存在或不存在的两种条件下,其反应方向是相同的,只是前者的反应速度更快一些。但必须指出的是,在酶不存在的情况下,底物可以通过其他不受催化的“自由”反应生成不同的产物,原因是这些不同产物的形成速度更快。 |

|||

Coenzymes are small organic molecules that can be loosely or tightly bound to an enzyme. Coenzymes transport chemical groups from one enzyme to another.<ref name = "Wagner_1975">{{cite book | author = Wagner AL | title = Vitamins and Coenzymes | publisher = Krieger Pub Co | year = 1975 | isbn = 0-88275-258-8}}</ref> Examples include [[Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide|NADH]], [[Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate|NADPH]] and [[adenosine triphosphate]] (ATP). Some coenzymes, such as [[riboflavin]], [[thiamine]] and [[folic acid]], are [[vitamins]], or compounds that cannot be synthesized by the body and must be acquired from the diet. The chemical groups carried include the [[hydride]] ion (H<sup>−</sup>) carried by [[nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide|NAD or NADP<sup>+</sup>]], the phosphate group carried by [[adenosine triphosphate]], the acetyl group carried by [[coenzyme A]], formyl, methenyl or methyl groups carried by [[folic acid]] and the methyl group carried by [[S-adenosylmethionine]].<ref name = "Wagner_1975"/> |

|||

酶可以连接两个或多个反应,因此可以用一个[[热力学]]上更容易发生的反应去“驱动”另一个热力学上不容易发生的反应。例如,细胞常常通过[[三磷酸腺苷|ATP]]被酶水解所产生的能量来驱动其他化学反应。<ref name=Nicholls>{{en}}{{cite book |author=Ferguson, S. J.; Nicholls, David; Ferguson, Stuart |title=Bioenergetics 3 |publisher=Academic |location=San Diego |year=2002 |isbn=0-12-518121-3 |edition=3rd}}</ref> |

|||

Since coenzymes are chemically changed as a consequence of enzyme action, it is useful to consider coenzymes to be a special class of substrates, or second substrates, which are common to many different enzymes. For example, about 1000 enzymes are known to use the coenzyme NADH.<ref>{{cite web | url = http://www.brenda-enzymes.org | title = BRENDA The Comprehensive Enzyme Information System | publisher = Technische Universität Braunschweig | accessdate = 23 February 2015 }}</ref> |

|||

酶可以同等地催化正向反应和逆向反应,而并不改变反应自身的化学平衡。例如,[[碳酸酐酶]]可以催化如下两个互逆反应,催化哪一种反应则是依赖于反应物浓度。<ref>{{en}}{{cite journal en|author=Maren TH|title=Carbonic anhydrase: chemistry, physiology, and inhibition|journal=Physiol Rev|volume=47|issue=4|year=1967|pages=595-781|pmid=4964060}}</ref> |

|||

Coenzymes are usually continuously regenerated and their concentrations maintained at a steady level inside the cell. For example, NADPH is regenerated through the [[pentose phosphate pathway]] and ''S''-adenosylmethionine by [[methionine adenosyltransferase]]. This continuous regeneration means that small amounts of coenzymes can be used very intensively. For example, the human body turns over its own weight in ATP each day.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Törnroth-Horsefield S, Neutze R | title = Opening and closing the metabolite gate | journal = Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America | volume = 105 | issue = 50 | pages = 19565–6 | date = December 2008 |pmid = 19073922 | pmc = 2604989 | doi = 10.1073/pnas.0810654106 | bibcode = 2008PNAS..10519565T }}</ref> |

|||

: <math>\mathrm{CO_2 + H_2O |

|||

{}^\mathrm{\quad *} |

|||

\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\! |

|||

\overrightarrow{\qquad} |

|||

H_2CO_3}</math> ([[組織|组织]]内;高[[二氧化碳|CO<sub>2</sub>]]浓度下) |

|||

: <math>\mathrm{H_2CO_3 |

|||

{}^\mathrm{\quad *} |

|||

\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\! |

|||

\overrightarrow{\qquad} |

|||

CO_2 + H_2O}</math> ([[肺]]中;低CO<sub>2</sub>浓度下) |

|||

==Thermodynamics== |

|||

<span style="font-size:smaller;"> 反应式中“*”表示“碳酸酐酶”</span> |

|||

[[File:Enzyme catalysis energy levels 2.svg|thumb|400px|alt=A two dimensional plot of reaction coordinate (x-axis) vs. energy (y-axis) for catalyzed and uncatalyzed reactions. The energy of the system steadily increases from reactants (x = 0) until a maximum is reached at the transition state (x = 0.5), and steadily decreases to the products (x = 1). However, in an enzyme catalysed reaction, binding generates an enzyme-substrate complex (with slightly reduced energy) then increases up to a transition state with a smaller maximum than the uncatalysed reaction.|The energies of the stages of a [[chemical reaction]]. Uncatalysed (dashed line), substrates need a lot of [[activation energy]] to reach a [[transition state]], which then decays into lower-energy products. When enzyme catalysed (solid line), the enzyme binds the substrates (ES), then stabilizes the transition state (ES<sup>‡</sup>) to reduce the activation energy required to produce products (EP) which are finally released.]] |

|||

{{main |Activation energy|Thermodynamic equilibrium|Chemical equilibrium}} |

|||

当然,如果反应平衡极大地趋向于某一方向,比如释放高能量的反应,而逆反应不可能有效的发生,则此时酶实际上只催化热力学上允许的方向,而不催化其逆反应。 |

|||

As with all catalysts, enzymes do not alter the position of the chemical equilibrium of the reaction. In the presence of an enzyme, the reaction runs in the same direction as it would without the enzyme, just more quickly.<ref name = "Stryer_2002"/>{{rp|8.2.3}} For example, [[carbonic anhydrase]] catalyzes its reaction in either direction depending on the concentration of its reactants:<ref>{{cite book |vauthors=McArdle WD, Katch F, Katch VL | title = Essentials of Exercise Physiology | date = 2006 | publisher = Lippincott Williams & Wilkins | location = Baltimore, Maryland | isbn = 978-0781749916 | pages = 312–3 | edition = 3rd | chapter = Chapter 9: The Pulmonary System and Exercise | chapterurl =https://books.google.com/books?id=L4aZIDbmV3oC&pg=PA313&lpg=PA313&dq=carbonic+anhydrase+lung+tissue+low+high+carbon+dioxide+equilibrium&source=bl&ots=WmoWpbFgYQ&hl=en&sa=X&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=carbonic%20anhydrase%20lung%20tissue%20low%20high%20carbon%20dioxide%20equilibrium&f=false}}</ref> |

|||

== 动力学 == |

|||

{{main|酶动力学}} |

|||

{{FileTA|Simple mechanism of enzyme reaction|png|thumb|left|300px|单一底物的酶催化反应机理:酶(表示为“E”)结合底物(表示为“S”),并通过催化反应生成产物(表示为“P”)。}} |

|||

{{Unsolved|化學|为什么一些酶的表现快于扩散动力学?}} |

|||

酶动力学是研究酶结合底物能力和催化反应速率的科学。研究者通过[[酶反应分析法]](enzyme assay)来获得用于酶动力学分析的反应速率数据。 |

|||

{{NumBlk|:| <math chem>\begin{matrix}{}\\ |

|||

1902年,[[维克多·亨利]]提出了酶动力学的定量理论;<ref>{{fr}}{{cite journal en |author=Henri,V.|year=1902|title= Theorie generale de l'action de quelques diastases|journal=Compt. rend. hebd. Acad. Sci. Paris|volume= 135|pages= 916-919}}</ref>随后该理论得到他人证实并扩展为[[米氏方程]]。<ref>{{de}}{{cite journal en |author=Michaelis L., Menten M.|year=1913|title= Die Kinetik der Invertinwirkung|journal=Biochem. Z.|volume= 49|pages= 333–369}} [http://web.lemoyne.edu/~giunta/menten.html English translation] Accessed 6 April 2007</ref>亨利最大贡献在于其首次提出酶催化反应由两步组成:首先,底物可逆地结合到酶上,形成酶-底物复合物;然后,酶完成对对应化学反应的催化,并释放生成的产物(见左图)。 |

|||

\ce{{CO2} + H2O ->[\ce{Carbonic\ anhydrase}] H2CO3}\\ |

|||

{}\end{matrix}</math> (in [[Biological tissue|tissues]]; high CO<sub>2</sub> concentration)|{{EquationRef|1}}}} |

|||

{{NumBlk|:| <math chem>\begin{matrix}{}\\ |

|||

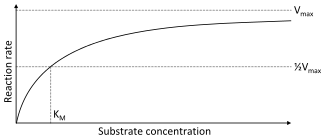

[[File:Michaelis-Menten.png|thumb|300px|酶初始反应速率(表示为“''V''”)与底物浓度(表示为“[S]”)的关系曲线。随着底物浓度不断提高,酶的反应速率也趋向于最大反应速率(表示为“''V''<sub>max</sub>”)。]] |

|||

\ce{H2CO3 ->[\ce{Carbonic\ anhydrase}] {CO2} + H2O}\\ |

|||

酶可以在一秒钟内催化数百万个反应。例如,[[乳清酸核苷5'-磷酸脱羧酶]]所催化的反应在无酶情况下,需要七千八百万年才能将一半的底物转化为产物;而同样的反应过程,如果加入这种脱羧酶,则需要的时间只有25[[数量级 (时间)|毫秒]]。<ref>{{en}}{{cite journal en |author=Radzicka A, Wolfenden R.|year= 1995|title= A proficient enzyme. |journal= Science |volume=6|issue=267|pages=90–931|id= PMID 7809611}}</ref>酶催化速率依赖于反应条件和底物浓度。如果反应条件中存在能够将蛋白解链的因素,如高温、极端的pH和高的盐浓度,都会破坏酶的活性;而提高反应体系中的底物浓度则会增加酶的活性。在酶浓度固定的情况下,随着底物浓度的不断升高,酶催化的反应速率也不断加快并趋向于最大反应速率(''V''<sub>max</sub>,见右图的饱和曲线)。出现这种现象的原因是,当反应体系中底物的浓度升高,越来越多自由状态下的酶分子结合底物形成酶-底物复合物;当所有酶分子的活性位点都被底物饱和结合,即所有酶分子形成酶-底物复合物时,催化的反应速率达到最大。当然,''V''<sub>max</sub>并不是酶唯一的动力学常数,要达到一定反应速率所需的底物浓度也是一个重要的动力学指标。这一动力学指标即[[米氏方程|米氏常数]](''K''<sub>m</sub>),指的是达到''V''<sub>max</sub>值一半的反应速率所需的底物浓度(见右图)。对于特定的底物,每一种酶都有其特征''K''<sub>m</sub>值,表示底物与酶之间的结合强度(''K''<sub>m</sub>值越低,结合越牢固,亲和力越高)。另一个重要的动力学指标是''k''<sub>cat</sub>,定义为一个酶活性位点在一秒钟内催化底物的数量,用于表示酶催化特定底物的能力。 |

|||

{}\end{matrix}</math> (in [[lung]]s; low CO<sub>2</sub> concentration)|{{EquationRef|2}}}} |

|||

酶的催化效率可以用''k''<sub>cat</sub>/''K''<sub>m</sub>来衡量。这一表示式又被称为特异性常数,其包含了催化反应中所有步骤的[[反应常数]]。由于特异性常数同时反映了酶对底物的亲和力和催化能力,因此可以用于比较不同酶对于特定底物的 |

|||

催化效率或同一种酶对于不同底物的催化效率。特异性常数的理论最大值,又称为扩散极限,约为10<sup>8</sup>至10<sup>9</sup> M<sup>−1</sup>s<sup>−1</sup>;此时,酶与底物的每一次碰撞都会导致底物被催化,因此产物的生成速率不再为反应速率所主导,而分子的扩散速率起到了决定性作用。酶的这种特性被称为“[[完美催化酶|催化完美性]]”或“动力学完美性”。相关的酶的例子有[[磷酸丙糖异构酶]]、[[碳酸酐酶]]、[[乙酰胆碱酯酶]]、[[过氧化氢酶]]、[[延胡索酸酶]]、β-内酰胺酶和[[超氧化物歧化酶]]。 |

|||

米氏方程是基于[[質量作用定律|质量作用定律]]而确立的,而该定律则基于自由扩散和热动力学驱动的碰撞这些假定。然而,由于酶/底物/产物的高浓度和相分离或者一维/二维分子运动,许多生化或细胞进程明显偏离质量作用定律的假定。<ref>{{en}}{{cite journal en |author=Ellis RJ |title=Macromolecular crowding: obvious but underappreciated |journal=Trends Biochem. Sci. |volume=26 |issue=10 |pages=597-604 |year=2001 |pmid=11590012}}</ref>在这些情况下,可以应用[[分形]]米氏方程。<ref>{{en}}{{cite journal en |author=Kopelman R |title=Fractal Reaction Kinetics |journal=Science |volume=241 |issue=4873 |pages=1620–26 |year=1988 |DOI=10.1126/science.241.4873.1620}}</ref><ref>{{en}}{{cite journal en |author=Savageau MA |title=Michaelis-Menten mechanism reconsidered: implications of fractal kinetics |journal=J. Theor. Biol. |volume=176 |issue=1 |pages=115-24 |year=1995 |pmid=7475096}}</ref><ref>{{en}}{{cite journal en |author=Schnell S, Turner TE |title=Reaction kinetics in intracellular environments with macromolecular crowding: simulations and rate laws |journal=Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. |volume=85 |issue=2–3 |pages=235-60 |year=2004 |pmid=15142746}}</ref><ref>{{en}}{{cite journal en |author=Xu F, Ding H |title=A new kinetic model for heterogeneous (or spatially confined) enzymatic catalysis: Contributions from the fractal and jamming (overcrowding) effects |journal=Appl. Catal. A: Gen. |volume=317 |issue=1 |pages=70–81 |year=2007 |doi=10.1016/j.apcata.2006.10.014 }}</ref> |

|||

The rate of a reaction is dependent on the [[activation energy]] needed to form the [[transition state]] which then decays into products. Enzymes increase reaction rates by lowering the energy of the transition state. First, binding forms a low energy enzyme-substrate complex (ES). Secondly the enzyme stabilises the transition state such that it requires less energy to achieve compared to the uncatalyzed reaction (ES<sup>‡</sup>). Finally the enzyme-product complex (EP) dissociates to release the products.<ref name = "Stryer_2002"/>{{rp|8.3}} |

|||

存在一些酶,它们的催化产物动力学速率甚至高于分子扩散速率,这种现象无法用目前公认的理论来解释。有多种理论模型被提出来解释这类现象。其中,部分情况可以用酶对底物的附加效应来解释,即一些酶被认为可以通过双偶极电场来捕捉底物以及将底物以正确方位摆放到催化活性位点。另一种理论模型引入了基于量子理论的[[量子穿隧效應|穿隧效应]],即质子或电子可以穿过激活能垒(就如同穿过隧道一般),但关于穿隧效应还有较多争议。<ref>{{en}}{{cite journal en |author= Garcia-Viloca M., Gao J., Karplus M., Truhlar D. G.|year= 2004|title= How enzymes work: analysis by modern rate theory and computer simulations.|journal= Science|volume=303|issue=5655|pages=186–195|id= PMID 14716003}}</ref><ref>{{en}}{{cite journal en |author=Olsson M. H., Siegbahn P. E., Warshel A.|year= 2004|title= Simulations of the large kinetic isotope effect and the temperature dependence of the hydrogen atom transfer in lipoxygenase|journal = J. Am. Chem. Soc.|volume=126|issue=9|pages=2820-1828|id= PMID 14995199}}</ref>有报道发现[[色胺]]中质子存在量子穿隧效应。<ref>{{en}}{{cite journal en |author=Masgrau L., Roujeinikova A., Johannissen L. O., Hothi P., Basran J., Ranaghan K. E., Mulholland A. J., Sutcliffe M. J., Scrutton N. S., Leys D.|year= 2006|title= Atomic Description of an Enzyme Reaction Dominated by Proton Tunneling|journal= Science| volume=312|issue=5771|pages=237–241|id= PMID 16614214}}</ref>因此,有研究者相信在酶催化中也存在着穿隧效应,可以直接穿过反应能垒,而不是像传统理论模型的方式通过降低能垒达到催化效果。有相关的实验报道提出在一种[[醇脫氫酶|醇脱氢酶]]的催化反应中存在穿隧效应,<ref>{{en}}{{cite journal en |author=Kohen, A., Cannio, R., Bartolucci, S., Klinman, J. P.|year= 1999|title= Enzyme dynamics and hydrogen tunnelling in a thermophilic alcohol dehydrogenase|journal= Nature| volume=399|issue=6735|pages=496-9|id= PMID 10365965}}</ref>但穿隧效应是否在酶催化反应中普遍存在并未有定论。<ref>{{en}}{{cite journal en |author=Ball, P.|year= 2004|title= Enzymes: by chance, or by design?|journal= Nature| volume=431|issue=7007|pages=396-7|id= PMID 15385982}}</ref> |

|||

Enzymes can couple two or more reactions, so that a thermodynamically favorable reaction can be used to "drive" a thermodynamically unfavourable one so that the combined energy of the products is lower than the substrates. For example, the hydrolysis of [[Adenosine triphosphate|ATP]] is often used to drive other chemical reactions.<ref name="Nicholls">{{cite book|vauthors=Ferguson SJ, Nicholls D, Ferguson S | title = Bioenergetics 3 | publisher = Academic | location = San Diego | year = 2002 | isbn = 0-12-518121-3 | edition = 3rd}}</ref> |

|||

== 抑制作用 == |

|||

{{main|酶抑制剂}} |

|||

酶的催化活性可以被多种抑制剂所降低。<ref>{{Cite book|author=Laurence A. Moran, Robert Horton, Gray Scrimgeour & Marc D. Perry|year=2011|title=Principles of Biochemistry (Fifth Edition)|trans_title=生物化学原理|publisher=[[培生出版集團]]|pages= 148-152|chapter= Properties of Enzymes|isbn=0-321-70733-8}}</ref> |

|||

==Kinetics== |

|||

{{FileTA|Inhibition|png|thumb|400px|不同的抑制类型。分类参考自<ref>{{en}}{{cite journal en |author=Cleland, W.W.|year=1963|title= The Kinetics of Enzyme-catalyzed Reactions with two or more Substrates or Products 2. {I}nhibition: Nomenclature and Theory|journal=Biochim. Biophys. Acta|volume= 67|pages= 173-187}}</ref>。图中,“E”表示酶;“I”表示抑制剂;“S”表示底物;“P”表示产物。}} |

|||

{{multiple image |

|||

=== 可逆抑制作用 === |

|||

| direction= vertical |

|||

可逆抑制作用的类型有多种,它们的共同特点在于抑制剂对酶活性的抑制反应具有可逆性。 |

|||

| width = 325 |

|||

| footer = |

|||

| image1 = Enzyme mechanism 2.svg |

|||

==== 竞争性抑制作用 ==== |

|||

| alt1 = Schematic reaction diagrams for uncatalzyed (Substrate to Product) and catalyzed (Enzyme + Substrate to Enzyme/Substrate complex to Enzyme + Product) |

|||

抑制剂与底物竞争结合酶的活性位点(抑制剂和底物不能同时结合到活性位点),也就意味着它们不能同时结合到酶上。<ref>{{en}}{{cite journal |author=Price, NC. |year=1979 |title=What is meant by 'competitive inhibition'? |journal=Trends in Biochemical Sciences |volume=4|pages=pN272 |doi=10.1016/0968-0004(79)90205-6 |issue=11}}</ref>对于竞争性抑制作用,催化反应的最大反应速率值没有变,但是需要更高的底物浓度,反映在表观''K''<sub>m</sub>值的增加。 |

|||

| caption1 = A chemical reaction mechanism with or without [[enzyme catalysis]]. The enzyme (E) binds [[substrate (chemistry)|substrate]] (S) to produce [[product (chemistry)|product]] (P). |

|||

| image2 = Michaelis Menten curve 2.svg |

|||

==== 非竞争性抑制作用 ==== |

|||

| alt2 = A two dimensional plot of substrate concentration (x axis) vs. reaction rate (y axis). The shape of the curve is hyperbolic. The rate of the reaction is zero at zero concentration of substrate and the rate asymptotically reaches a maximum at high substrate concentration. |

|||

非竞争性抑制抑制剂可以与底物同时结合到酶上,即抑制剂不结合到活性位点。酶-抑制剂复合物(EI)或酶-抑制剂-底物复合物(EIS)都没有催化活性。与竞争性抑制作用相比,非竞争性抑制作用不能通过提高底物浓度来达到所需反应速度,即表观最大反应速率''V''<sub>max</sub>的值变小;而同时,由于抑制剂不影响底物与酶的结合,因此''K''<sub>m</sub>值保持不变。 |

|||

| caption2 = [[Michaelis–Menten kinetics|Saturation curve]] for an enzyme reaction showing the relation between the substrate concentration and reaction rate. |

|||

}} |

|||

{{main|Enzyme kinetics}} |

|||

==== 反竞争性抑制作用 ==== |

|||

反竞争性抑制作用比较少见:抑制剂不能与处于自由状态下的酶结合,而只能和酶-底物复合物(ES)结合,在酶反应动力学上表现为''V''<sub>max</sub>和''K''<sub>m</sub>值都变小。这种抑制作用可能发生在多亚基酶中。 |

|||

Enzyme kinetics is the investigation of how enzymes bind substrates and turn them into products. The rate data used in kinetic analyses are commonly obtained from [[enzyme assay]]s. In 1913 [[Leonor Michaelis]] and [[Maud Leonora Menten]] proposed a quantitative theory of enzyme kinetics, which is referred to as [[Michaelis–Menten kinetics]].<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Michaelis L, Menten M | year = 1913 | title = Die Kinetik der Invertinwirkung | journal = Biochem. Z. | volume = 49 | pages = 333–369 | language = German |trans-title = The Kinetics of Invertase Action }}; {{cite journal | vauthors = Michaelis L, Menten ML, Johnson KA, Goody RS | title = The original Michaelis constant: translation of the 1913 Michaelis-Menten paper | journal = Biochemistry | volume = 50 | issue = 39 | pages = 8264–9 | year = 2011 | pmid = 21888353 | pmc = 3381512 | doi = 10.1021/bi201284u }}</ref> The major contribution of Michaelis and Menten was to think of enzyme reactions in two stages. In the first, the substrate binds reversibly to the enzyme, forming the enzyme-substrate complex. This is sometimes called the Michaelis-Menten complex in their honor. The enzyme then catalyzes the chemical step in the reaction and releases the product. This work was further developed by [[George Edward Briggs|G. E. Briggs]] and [[J. B. S. Haldane]], who derived kinetic equations that are still widely used today.<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors = Briggs GE, Haldane JB | title = A Note on the Kinetics of Enzyme Action | journal = The Biochemical Journal | volume = 19 | issue = 2 | pages = 339–339 | year = 1925 |pmid = 16743508 | pmc = 1259181 | doi=10.1042/bj0190338}}</ref> |

|||

==== 复合抑制作用 ==== |

|||

这种抑制作用与非竞争性抑制作用比较相似,区别在于EIS复合物残留有部分酶的活性。在许多生物体中,这类抑制剂可以作为[[负反馈|负反馈机制]]的组成部分。若一个酶体系生产了过多的产物,那么产物就会抑制合成该产物的酶体系中第一个酶的活性,这就可以保证一旦合成足够多的产物后,该产物的合成速率会下降或停止。受这种抑制作用调控的酶通常为多亚基酶,并具有与调控产物结合的别构结合位点。这种抑制作用的反应速率与底物浓度的关系图不再是双曲线形而是S形。 |

|||

Enzyme rates depend on [[solution]] conditions and substrate [[concentration]]. To find the maximum speed of an enzymatic reaction, the substrate concentration is increased until a constant rate of product formation is seen. This is shown in the saturation curve on the right. Saturation happens because, as substrate concentration increases, more and more of the free enzyme is converted into the substrate-bound ES complex. At the maximum reaction rate (''V''<sub>max</sub>) of the enzyme, all the enzyme active sites are bound to substrate, and the amount of ES complex is the same as the total amount of enzyme.<ref name = "Stryer_2002"/>{{rp|8.4}} |

|||

=== 不可逆抑制作用 === |

|||

不可逆抑制剂可以与酶结合形成[[共价键|共价连接]],而其他抑制作用中酶与抑制剂之间都是非共价结合。这种抑制作用是不可逆的,酶一旦被抑制后就无法再恢复活性状态。这类抑制剂包括[[二氟甲基鸟氨酸]](一种可用于治疗寄生虫导致的[[昏睡症]]的药物<ref name=Poulin>{{en}}Poulin R, Lu L, Ackermann B, Bey P, Pegg AE. [http://www.jbc.org/cgi/reprint/267/1/150 ''Mechanism of the irreversible inactivation of mouse ornithine decarboxylase by alpha-difluoromethylornithine. Characterization of sequences at the inhibitor and coenzyme binding sites.''] J Biol Chem. 1992 Jan 5;267 (1):150–8. PMID 1730582</ref>)、[[苯甲基磺酰氟]](PMSF)、[[青霉素]]和[[阿司匹林]]。这些药物都是与酶活性位点结合并被激活,然后与活性位点处的一个或多个氨基酸残基发生不可逆的反应形成共价连接。 |

|||

''V''<sub>max</sub> is only one of several important kinetic parameters. The amount of substrate needed to achieve a given rate of reaction is also important. This is given by the[[Michaelis-Menten constant]] (''K''<sub>m</sub>), which is the substrate concentration required for an enzyme to reach one-half its maximum reaction rate; generally, each enzyme has a characteristic ''K''<sub>m</sub> for a given substrate. Another useful constant is ''k''<sub>cat</sub>, also called the ''turnover number'', which is the number of substrate molecules handled by one active site per second.<ref name = "Stryer_2002"/>{{rp|8.4}} |

|||

=== 抑制剂的用途 === |

|||

酶抑制剂常被用作药物,同样也可以被作为毒药使用。而药物和毒药之间的差别通常非常小,大多数的药物都有一定程度的毒性,正如[[帕拉塞尔苏斯]]所言:“所有东西都有毒,没有什么是无毒的”(“In all things there is a poison, and there is nothing without a poison”)。<ref>{{en}}Ball, Philip (2006) ''The Devil's Doctor: Paracelsus and the World of Renaissance Magic and Science.'' Farrar, Straus and Giroux ISBN 978-0-374-22979-5</ref>相同的,[[抗生素]]和其他抗感染药物只是特异性地对[[病原|病原体]]而不是对[[宿主]]有毒性。 |

|||

The efficiency of an enzyme can be expressed in terms of ''k''<sub>cat</sub>/''K''<sub>m</sub>. This is also called the specificity constant and incorporates the [[rate constant]]s for all steps in the reaction up to and including the first irreversible step. Because the specificity constant reflects both affinity and catalytic ability, it is useful for comparing different enzymes against each other, or the same enzyme with different substrates. The theoretical maximum for the specificity constant is called the diffusion limit and is about 10<sup>8</sup> to 10<sup>9</sup> (M<sup>−1</sup> s<sup>−1</sup>). At this point every collision of the enzyme with its substrate will result in catalysis, and the rate of product formation is not limited by the reaction rate but by the diffusion rate. Enzymes with this property are called ''[[catalytically perfect enzyme|catalytically perfect]]'' or''kinetically perfect''. Example of such enzymes are [[triosephosphateisomerase|triose-phosphate isomerase]], [[carbonic anhydrase]], [[acetylcholinesterase]], [[catalase]],[[fumarase]], [[β-lactamase]], and [[superoxide dismutase]].<ref name = "Stryer_2002"/>{{rp|8.4.2}} The turnover of such enzymes can reach several million reactions per second.<ref name = "Stryer_2002"/>{{rp|9.2}} |

|||

一个获得广泛应用的抑制剂药物是[[阿司匹林]],它可以抑制[[环加氧酶]]的活性,而环加氧酶可以生产[[炎症]]反应信使[[前列腺素]],因此,阿司匹林可以起到抑制疼痛与炎症的作用。而剧毒毒药[[氰化物]]可以通过结合[[细胞色素氧化酶]]位点处的铜和铁原子不可逆地抑制酶活性,从而抑制细胞的[[呼吸作用]]。<ref>{{en}}{{cite journal en |url=http://www.jbc.org/cgi/reprint/265/14/7945|author=Yoshikawa S and Caughey WS.|volume=265|issue=14|title= Infrared evidence of cyanide binding to iron and copper sites in bovine heart cytochrome c oxidase. Implications regarding oxygen reduction.|journal= J Biol Chem.|pages= 7945–7958|id= PMID 2159465|date=May 1990}}</ref> |

|||