白蚁

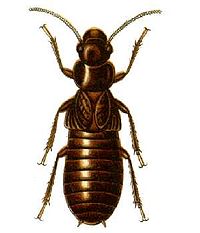

| 白蚁 化石时期:白垩纪-现代

| |

|---|---|

| |

| 台湾家白蚁 Coptotermes formosanus | |

| 科学分类 | |

| 界: | 动物界 Animalia |

| 门: | 节肢动物门 Arthropoda |

| 纲: | 昆虫纲 Insecta |

| 目: | 蜚蠊目 Blattodea |

| 下目: | 等翅下目 Isoptera Brullé, 1832 |

| 科 | |

白蚁,亦称

白蚁旧时分类位阶为等翅目,但近期系统发生学证据显示白蚁为蜚蠊目,姊妹群为隐尾蠊属(Cryptocercus )[2],现降级为蜚蠊目等翅下目或白蚁上科(学名:Termitoidae)。共有超过3,000个物种,可见于热带及亚热带地区[3],可分为12个科,其中3个科已灭绝。以前的研究认为白蚁起源于侏罗纪或三叠纪,但近期研究认为其起源于白垩纪[4],最早的白蚁化石年代为白垩纪中期。

白蚁为不完全变态,生活史包括卵、若虫、成虫,可分为多个阶级,有不具生殖能力的工蚁和兵蚁,和具有生殖能力的蚁王蚁后。大部分白蚁取食死亡的植物组织,和含有纤维素的木材、落叶、土壤或动物粪便。白蚁的群体大小因物种而异,个体数量少至百只内,多至数百万。蚁后的寿命乃昆虫之最,有纪录显示蚁后能活30至50年。

除了南极洲以外,白蚁的足迹遍布全球,热带与亚热带地区的白蚁丰富度和多样性最高,白蚁能分解木材和植物组织,是生态系统中不可或缺的一员。

白蚁在某些文化中是美食,也被用于传统疗法。数百种白蚁是经济害虫,会危害建筑、作物和森林,有些物种是世界广布的入侵种,如西印度干木白蚁(Cryptotermes brevis)。

描述

[编辑]

大部分白蚁体型较小,体长约 4-15 毫米[5]。现生最大的白蚁是 Macrotermes bellicosus 的蚁后,体长可以超过 10 公分[6]。还有一种已灭绝的白蚁 Gyatermes styriensis 体长约 25 毫米,翼展 76 毫米,该物种栖息于中新世的奥地利[7][注 2]。

大部分白蚁的工蚁和兵蚁没有眼睛,有些则有简单的复眼,如 Hodotermes mossambicus ,可以用来分辨方向并感知阳光及月光[8]。大部分有翅生殖型有复眼和侧单眼,但是原白蚁科和古原白蚁科的则没有侧单眼[9][10]。白蚁上唇为舌状,上唇上方连著头楯,头楯可分为前头楯和后头楯两个部分。白蚁触角有很多种功能,如触觉、味觉、嗅觉(包含接收费洛蒙)、感热和感知震动。触角可分为三个部分:柄节(第一节)、梗节(第二节,通常较柄节短)和鞭节(其馀的节[10])。口器包含小颚、下唇、大颚,小颚和下唇生有须,可以帮助白蚁感知并抓握食物[10]。

白蚁的胸部包含三个部分:前胸、中胸和后胸[10],各生有一对足。有翅生殖型的翅膀生于中胸和后胸发达的骨片上,前胸的骨片较不发达[11]。

白蚁的腹部共有 10 节[12]。第十腹节生有一对短尾毛(cerci)[13]。白蚁的生殖器类似于蟑螂的,但较为简化,如雄虫没有阴茎,且精子不具移动能力或无鞭毛,但在澳白蚁科中,精子有鞭毛且具有些微移动能力[14]。雌虫的生殖器也较为简化,但澳白蚁科和其他白蚁不同,澳白蚁科雌虫具有产卵管,这个特征与蟑螂雌虫极为相似[15]。

非生殖阶级无翅,依赖六肢移动,有翅生殖型飞行的时间只占一小部分,因此他们也是靠六肢移动[12]。每个阶级的脚形态相似,除了兵蚁的脚较大较粗壮。白蚁的脚由基节、转节、腿节、胫节和附节组成[12]。胫节刺的数量因种类而异。有些物种具有爪间体,爪间体是擅爬光滑表面的昆虫会有的构造,但大多白蚁没有[16]。

跟蚂蚁不同的是,白蚁的前翅和后翅长度相等[17]。白蚁不太擅长飞行,他们的飞行策略是飞上天以后往随机的方向去[18]。研究显示大型白蚁飞行的距离比小型白蚁长。白蚁飞行时翅膀与身体垂直,没有飞行时则与身体平行[19]。

阶级分工

[编辑]

工蚁

[编辑]工蚁负责群体中大多数的工作,如觅食、管理储粮、照顾幼代和打理蚁巢[20][21]。工蚁负责消化纤维素,因此,在被蛀食的木材中发现的大多是工蚁。工蚁喂食其他个体的行为被称作交哺(trophallaxis),交哺是有效的营养供给方法,且利于含氮物质循环[22],交哺让亲代不必负责喂养每一个子代,交哺有利于群体个体数成长,且能保证巢中每个个体都能获得共生原生动物。有些白蚁的若虫也会负责工蚁的工作[20]。工蚁雌雄都有,但通常不具有生育能力,特别是巢食分离型的物种。 工蚁两种性别都有,但是生殖器官退化不具功能。工蚁可分为假工蚁(pseudergate)和真工蚁(worker)。大部分低等白蚁的工蚁都是假工蚁,假工蚁可以继续蜕皮分化;而真工蚁则无法继续蜕皮进行分化。依照物种不同,假工蚁可以透过蜕皮分化为真工蚁、兵蚁、有翅型、补充繁殖型。有些学者会将无生殖能力的工蚁称作真工蚁(True worker),而具生殖能力的工蚁则被称作假工蚁(Pseudergate),如原白蚁科[23]。

兵蚁

[编辑]兵蚁不论形态或行为都和工蚁相异,他们的功能是保卫群体[24]。很多物种的兵蚁具有极大的头部和高度特化的大颚,他们甚至无法自行取食,仰赖工蚁喂食[24][25]。窗点(Fontanelle) 是前额上的一个小孔,可以分泌防御性的分泌物,窗点是鼻白蚁科的特征[26]。很多物种都可以靠兵蚁的特征来分辨,如头部和大颚[20][24]。有些物种的兵蚁头部为截面型(phragmotic),可以用来阻塞通道,如截头堆沙白蚁[27]。兵蚁种类因物种而异,如小兵蚁、大兵蚁或象鼻型兵蚁(nasutes),象鼻型兵蚁的窗点特化,形成一个角状的突出结构[20],能喷出含有双萜类(diterpene) 的分泌物来攻击敌人[28]。固氮作用对象白蚁很重要,是他们获取营养的来源之一[29]。兵蚁通常不具有生殖能力,但有些原白蚁科的物种有具有生殖能力且头部类似兵蚁的个体,称作补充繁殖型兵蚁(neotenic soldiers)[30]。 不同物种兵蚁形态不同,依据形态可分为以下几种:

- 大颚型兵蚁,用大颚咬敌人,如土白蚁属 (Odonotermes )。

- 弹击型兵蚁,大颚修长,可分为对称型与不对称型,两大颚互相挤压累积弹性位能,再透过瞬间释放造成极高的速度,弹击目标。不对称型大颚如新渡户歪白蚁,其大颚弹击速度为动物界中最快的运动速度。

- 阻塞型兵蚁,头部高度骨化,且额部扁平,巢体受破坏时能以头部塞住破口,如截头堆沙白蚁(Cryptotermes domesticus )。

- 象鼻型兵蚁,头部额部 (frons) 的窗点 (fontanelle) 特化,延伸成象鼻状 (Nasute),可分泌化学物质涂抹敌人造成伤害,如象白蚁亚科(Nasutitermitinae)。

生殖型

[编辑]生殖型包含雌虫和雄虫,称作蚁后和蚁王[31],蚁后负责产卵,蚁王负责让卵受精[32]。在某些物种中,蚁后的腹部会随著时间膨胀,提高生殖能力,这种现象称作“腹膨大(physogastrism)”[31]。有翅生殖型会在一年中的某些特定时间出现,而这特定时间因物种而异,等到婚飞的时候来临,有翅生殖型会倾巢而出,同时吸引大量掠食者前来[31]。

台湾家白蚁、格斯特家白蚁,和台湾土白蚁的有翅繁殖型常会在空气湿度高的温暖夏夜倾巢而出,尤其是台湾土白蚁常在下过雨的夜晚婚飞,又因其具有趋光性,婚飞时常常涌入民众家中或是光源处(路灯下),有时婚飞规模庞大,常会吸引民众目光[33],这类有翅繁殖型俗称大水蚁。

生殖型可分二类:有翅型及补充生殖型,在群体中负责生殖后代。

- 有翅型 (alate) 为白蚁主要的繁殖方式,又称主要生殖型(primary reproductive)。有翅型个体生殖器官功能正常,靠飞行进行长距离移动,交配后建立新群体,成为创始蚁王蚁后,在某些白蚁(如台湾土白蚁)中,蚁后的卵巢会随著时间渐渐发育,导致腹部膨大。

- 补充生殖型 (neotenic)为有翅型以外的具有繁殖能力的个体,又称次要生殖型(secondary reproductive) 。可粗分为短翅型 (brachypterous) 与无翅型 (apterous),在某些物种中可以在创建群体的有翅型死后填补生殖的功能,如黄原鼻白蚁。

语源学

[编辑]Isoptera 源于希腊文,Iso 意思为相等(equal),Ptera 意思为翅膀(winged),命名由来是因为白蚁的前后翅大小几乎相等[34]。Termite 为晚期拉丁文,是林奈于1781年创造的拉丁词汇[35],和 terere(摩擦、耗损、侵蚀)有关,源于早期拉丁文的 tarmes 。蚁巢称作 terminarium 或 termitaria [36][37]。在早期的英文中,白蚁称作 wood ants 或 white ants [36]。

在德语中,白蚁又称“Unglückshafte”,意为“带有厄运的动物”或“带来不幸的动物”。

法语:Formic de blanc,意思为白蚁。

英语:White ant,意思为白蚁。

中文:白蚁。

分类学与演化

[编辑]

白蚁旧时被分作等翅目(Isoptera),但后来根据分子生物学证据将白蚁并入蜚蠊目。

Cleveland 于1934年发现白蚁和隐尾蠊的肠内具有类似的原生生物,推论白蚁和隐尾蠊亲缘关系接近[38]。McKittrick F. A. 于1965年提到某些白蚁和隐尾蠊若虫具有相似特征,进一步支持了白蚁和隐尾蠊接近的假说[39]。2008 年根据 16S rRNA 的 DNA 分析结果支持白蚁于演化树上的位置被包覆在蜚蠊目之中[40][41][42]。隐尾蠊属和白蚁为姊妹群[43][44],白蚁和隐尾蠊的形态和行为都有相似之处,如:大多蜚蠊没有社会性,但隐尾蠊会育幼,甚至还会交哺和社会性梳理[45]。有学者认为白蚁是从隐尾蠊演化而来[41][46],有些学者把白蚁分在白蚁上科(Termitoidae)中,白蚁上科中包含白蚁和隐尾蠊属[47]。学者认为白蚁接近蟑螂和螳螂,因此将白蚁也分入网翅总目中[48][49]。 最古老的白蚁化石可追溯至白垩纪早期,但根据白垩纪白蚁的多样性,和包裹在白垩纪化石中的共生原生动物,部分学者推测白蚁起源的年代可能是侏罗纪或三叠纪[50][51][52]。扶鲁塔食蚁兽(Fruitafossor ) 形态类似于现代专食白蚁的哺乳类[53],科学家推测其专食白蚁,它的生存年代为晚侏罗世,学者因此推测白蚁起源于侏罗纪。最古老的白蚁巢年代为晚侏罗世,地点为德州西部,最古老的粪球也发现于德州西部[54]。若试图将白蚁起源推得更早,可能会面临争议,如:Weesner F. M. 曾指出澳白蚁科的起源可追溯至晚二叠世,也就是2亿5千万年前[3],同时,堪萨斯州的二叠纪沉积层中出土了类似于澳白蚁属的翅膀化石[55]。白蚁的起源甚至可追溯至石炭纪[56]。木蜚蠊 Pycnoblattina 的翅膀与澳白蚁相似,现代的昆虫中只有澳白蚁和它相似[55]。然而 Krishna 等人(2003) 认为古生代和三叠纪的白蚁事实上并非白蚁,且应从等翅目中移除[57]。其他研究推论白蚁的起源较晚,是白垩纪早期时从隐尾蠊属演化而来[58]。

达尔文澳白蚁(Mastotermes darwiniensis ) 有很多类似于蟑螂,且其他白蚁没有的特征,如具有卵鞘、翅具有臀叶[59]。有学者提议将白蚁和隐尾蠊科放在同一个分支木食总科(Xylophagodea) 中[60]。白蚁有时候会被误认为白色的蚂蚁,但两者除了都具有真社会性以外别无相似之处,而真社会性乃是由趋同演化而来,并非由亲缘关系[61][62],而白蚁是世界上第一种真社会性昆虫,其真社会性早已出现超过1亿年[63]。跟其他昆虫比起来,白蚁的基因体较大,第一个被全基因体解序的白蚁是 Zootermopsis nevadensis ,发表于 Nature Communications 期刊上,其序列大小约为 500Mb[64],而后续两种被全基因体解序的白蚁分别为 Macrotermes natalensis 和 Cryptotermes secundus ,其序列大小约为 1.3Gb[62][65]。

| 网翅总目(Dictyoptera) |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

}} | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

至 2013 年,大约有 3106 种白蚁被发表,包含现生的和化石中的,共分为 12 个科。通常需透过兵蚁和繁殖蚁才能鉴定物种。等翅下目被划分为两个分支和数个科群,每个科下又分别有数个亚科,如以下所示[57]:

白蚁基群

[编辑]- Epifamily Termitoidae

- †科 Cratomastotermitidae

- 澳白蚁科 Mastotermitidae

- 小目 Euisoptera

- 原白蚁科 Termopsidae

- 科 Archotermopsidae

- 草白蚁科 Hodotermitidae

- 科 Stolotermitidae

- 木白蚁科 Kalotermitidae

新等翅类群

[编辑]新等翅类群(Neoisoptera),意思为“新的白蚁”,在演化的历史上新等翅类群是比较晚出现的类群,新等翅类群在分类位阶上属“从目(nanorder)”。新等翅类群中包含白蚁科,白蚁科没有假工蚁(Pseudergates)。白蚁科肠道内有共生真核细菌帮助消化纤维素[66],有些物种甚至会和Termitomyces 属的真菌共生,而低等白蚁肠道内则含有原生动物和原核细菌。

以下为新等翅类群下的五个科:

|

|

分布与多样性

[编辑]除南极洲外的大陆都有纪录。北美洲和欧洲的多样性较低(欧洲已知10种,北美已知50种),南美洲多样性较高,已知超过400种[67]。目前已发表3000多种白蚁,其中1000多种栖息于非洲,非洲有些地区的蚁冢数量极多,光是克留格尔国家公园北部就有1100万个白蚁蚁冢[68]。亚洲有435种白蚁,大部分分布于中国长江以南的微热带及亚热带地区[67]。澳洲已知超过360种白蚁,大多是特有种[67]。

白蚁无法栖息于寒冷地区,因其表皮较柔软[69]。白蚁可依栖地粗分为三类:腐木白蚁(原白蚁科)、干木白蚁(木白蚁科)、地下白蚁(鼻白蚁科),腐木白蚁栖息于针叶林,干木白蚁栖息于阔叶林,地下白蚁则广泛分布[67]。西印度干木白蚁(Cryptotermes brevis ) 在澳洲是入侵种[70]。

| 亚洲 | 非洲 | 北美洲 | 南美洲 | 欧洲 | 澳洲 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 估计物种数 | 435 | 1,000 | 50 | 400 | 10 | 360 |

生命周期

[编辑]

白蚁常常和社会性膜翅目(蚂蚁和一些蜂类)被放在一起讨论,但它们的生命周期差异甚大。真社会性膜翅目的工虫都是雌性,雄性是由未受精卵发育而来的单套体(n),雌性则是由受精卵发育而来的双套体(2n),而白蚁的工蚁两性皆有,且都为受精卵发育而来的双套体(2n)。根据白蚁物种不同,雄虫和雌虫负责的工作可能不同[71]。

白蚁的生命周期为卵、幼虫、成虫,这种没有经过蛹期的生命周期称作不完全变态[72]。幼虫的外形类似缩小版的成虫,它们透过蜕皮来长大,在 Cryptotermes dudleyi 中,幼虫(卵孵化出的个体)会经历四次蜕皮,而若虫(将来会发育成有翅型的个体)会经历三次蜕皮,最终成为有翅型[73]。若虫可以透过蜕皮变成兵蚁或有翅型[74]。

从若虫发育成有翅型的过程耗时数个月,具体时间会受食物多寡、气温、群体中个体数量影响。若虫无法自行取食,需透过工蚁喂食,工蚁的其他工作包含觅食、建造或修缮蚁巢、照顾蚁王蚁后[20][75]。费洛蒙调节白蚁的阶级分化,让大部分的个体无法成为繁殖阶级,只有极少部分有机会生育[76]。

Reticulitermes speratus 的蚁后寿命很长,且生殖能力不会随著时间下降。Reticulitermes speratus 的蚁后所受到的氧化压力(包含氧化性 DNA 损伤,oxidative DNA damage)比工蚁、兵蚁和若虫都小很多[77],因为这个物种的蚁后具有较多的过氧化氢酶,过氧化氢酶是一种可以抵挡氧化压力的催化物[77]。

繁殖

[编辑]

有翅繁殖型只会在分飞时离开蚁巢。雌雄虫会两两配对然后建立新的群体[78],蚁王蚁后只有在找到适合的地方筑巢以后才会交配,它们会挖出一个腔室,关上入口然后交配[78],之后,蚁王蚁后永远不会离开蚁巢。分飞时间因物种而异,有些物种在夏日白天分飞,有些在冬天白天分飞[79],也有在黄昏时分飞的物种,有翅型通常会被灯光吸引而大量聚集。分飞与否决定于环境因子,如时间、湿度、风速、降雨量[79]。群体中的个体数因物种而异,体型较大的物种个体数通常介于 100-1,000,有些物种个体数则可高达几百万只[7]。

在新群体建立的一开始,蚁后只会产下 10-20 颗卵,但群体建立数年后的蚁后一天可产下 1,000 颗卵[20]。成熟群体的创始蚁后(primary queen) 的产卵能力很强,它的腹部会膨胀,且一天可产下 40,000 颗卵[80]。一对成熟的卵巢各有大约 2,000 个卵巢管[81]。膨大的腹部让蚁后的体型大了好几倍,导致蚁后失去移动能力,需要工蚁协助移动。

蚁王只会长大一点点,而且会一辈子持续的和蚁后交配(蚁后寿命可达30至50年),这点和蚂蚁不同,蚂蚁的蚁后只和雄蚁交配一次便能储存能用上一辈子的精子,而雄蚁在交配完便会死去[32][75]。如果蚁后死了,蚁王会制造能诱发新蚁后发育的费洛蒙[82]。蚁王蚁后是一夫一妻制的,所以不会为了抢夺交配权竞争[83]。

白蚁透过不完全变态来变成有翅型,而在有些物种中,有补充繁殖型的阶级,它们会在蚁王或蚁后死亡或消失在群体中时发育成繁殖型[74][84]。补充繁殖型有能力取代死去的蚁王蚁后,且一个群体中可以有多个补充繁殖型[20]。有些物种蚁后可以行无性繁殖,研究显示蚁后会和蚁王交配产下工蚁,但也会行无性繁殖产下自己的补充繁殖型(neotenics)[85][86]。

在亚热带地区的白蚁 Embiratermes neotenicus 和其他近缘的物种中,一个群体包含一对创始蚁王蚁后和高达200只补充繁殖型蚁后,这些补充繁殖型蚁后是透过雌性单性生殖产生[87],这种方式可以确保配子异质性,从而避免近亲繁殖导致基因衰败。

行为和生态学

[编辑]食性

[编辑]

白蚁为食碎屑者,于生态系中扮演重要的角色,负责分解死木、粪便或植物组织[88][89][90]。很多物种都取食纤维素,肠道特化可分解植物纤维[91]。白蚁被认为是大气中甲烷的主要来源之一(11%),因其分解纤维素时会产生甲烷,甲烷是主要的温室气体之一[92]。白蚁依赖肠道内的共生原生动物分解纤维素,白蚁会吸收纤维素被分解后的产物作为养分[93][94],而原生动物(如Trichonympha)则依赖附著于它们体表的共生细菌分泌消化酶。白蚁科可自行分泌纤维素酶,但它们仍然仰赖细菌分解大部分的纤维素,白蚁科没有肠道共生原生动物[95][96][97]。白蚁消化系统与肠道共生物的关系仍需更多研究。根据肠道内原生动物亲缘关系,白蚁和隐尾蠊的原生动物可能是从共祖得来[98]。

某些物种食性会依季节改变,如 Gnathamitermes tubiformans 夏天偏好取食 Aristida longiseta ,5月至8月偏好取食野牛草,春天、夏天和秋天偏好取食格兰马草。Gnathamitermes tubiformans 秋天时比较活跃,因此所需要的食物量大于春天[99]。

木头的不同状态会影响白蚁取食与否,相关因子包含湿度、材质、硬度、树脂和木质素的含量。研究指出 Cryptotermes brevis 强烈偏好取食杨属和枫属的木材,而这两属的木材是大部分白蚁不吃的[100]。

有些白蚁会种植真菌。白蚁会建造菌圃,种植 Termitomyces 属的真菌。当白蚁吃下孢子,孢子会完好的通过白蚁的肠道,最后随著粪便离开白蚁体内,并在菌圃上成长[101][102]。分子证据显示大白蚁亚科种植真菌的行为起源于3100万年前。推测在非洲和亚洲半干燥莽原(semiarid savannah) 中,9成的木材都由大白蚁亚科的物种分解。大白蚁亚科起源于雨林,种植真菌的行为使它们能够扩殖非洲莽原,最终扩张到亚洲[103]。

白蚁可根据食性粗分为两大类:高等白蚁和低等白蚁。低等白蚁主要取食木材,由于一般的木材难以消化,白蚁偏好于取食受真菌感染的木材,真菌感染的木材较容易消化,且真菌富含蛋白。高等白蚁食性多样,取食粪便、腐植质、草、落叶和根[104]。低等白蚁肠道内含有很多种细菌和原生动物,而高等白蚁只有少数几种细菌且无原生动物[105]。

共生

[编辑]高等白蚁 (higher termites) 是指白蚁科,其他非白蚁科的白蚁称为低等白蚁 (lower termites)。高低等白蚁一个主要的差异在于高等白蚁的肠道内没有共生原生动物。

体内共生

[编辑]白蚁依靠后肠内的生物来协助他们分解纤维素,低等白蚁主要依靠原生动物,高等白蚁肠内则没有原生动物,它们靠细菌来协助他们分解纤维素。白蚁肠道内的原生动物共有两门,分别为副基体纲和前轴柱纲 (Preaxostyla) ,其中前轴柱纲的原生动物皆属于锐滴虫目 (Oxymonadida)[106]。

体外共生

[编辑]白蚁科中的大白蚁亚科会盖菌圃,并种植真菌,取食孢子。台湾土白蚁 (Coptotermes formosanus ) 与鸡肉丝菇 (Termitomyces eurhizus ) 共生,鸡肉丝菇的孢子中含有色胺酸(tryptophan),色胺酸为必需胺基酸,台湾土白蚁无法自行合成色胺酸,只能借由摄食鸡肉丝菇的孢子取得[107]。

天敌

[编辑]

白蚁有很多天敌,曾有研究指出 65 种鸟类和 19 种哺乳类会取食 Hodotermes mossambicus [108]。蚂蚁[109][110]、蜈蚣、蟑螂、蟋蟀、蜻蜓、蝎子、蜘蛛[111]、蜥蜴[112]、青蛙[113]都会吃白蚁,有两种 Ammoxenidae 科的蜘蛛专食白蚁[114][115][116]。土豚、土狼、食蚁兽、蝙蝠、熊、兔耳袋狸、许多鸟类、针鼹、狐狸、婴猴、袋食蚁兽、老鼠和穿山甲也会取食白蚁[114][117][118][119]。

土狼是一种专食昆虫的哺乳类,主食为白蚁。土狼透过声音寻找猎物,也会透过白蚁兵蚁释放的味道寻找白蚁。一只土狼用长又黏的舌头取食白蚁,一个晚上可以吃掉上千只白蚁[120][121]。懒熊会用爪破坏蚁丘,而黑猩猩则会使用工具把白蚁“钓”出蚁巢。根据骨制工具上的使用痕迹,学者认为罗百氏傍人会用工具破坏蚁丘[122]。

蚂蚁是白蚁最主要的天敌[109][110],有些种类的蚂蚁专食白蚁,如 Megaponera 属,Megaponera 属只吃白蚁,它们会行军捕食白蚁,行军时间可维持数小时[123][124];Paltothyreus tarsatus 也会行军捕食白蚁,它们会用大颚抓住尽可能多的白蚁带回家,在行军途中它们会沿途留下化学讯息,其他个体会沿著化学讯息加入行军[109];Eurhopalothrix heliscata 则会从朽木的缝隙进入,猎捕居住在朽木中的白蚁[109];Tetramorium uelense 则猎食小型白蚁,在外觅食的工蚁侦查到白蚁后会带来10到30只的工蚁一起猎捕,它们会用螫针使白蚁失去行动能力[125];Centromyrmex 和虹琉璃蚁属有时候会在蚁丘内筑巢并取食白蚁,但除了猎食以外,白蚁和这两属的蚂蚁并没有其他交互关系[126][127];其他蚂蚁如Acanthostichus 、巨山蚁属、举尾家蚁属(Crematogaster )、Cylindromyrmex、细颚针蚁属(Leptogenys )、锯针蚁属、Ophthalmopone、Pachycondyla、Rhytidoponera、火家蚁属、Wasmannia 也会取食白蚁[109][117][128]。矛蚁属则很少会取食白蚁,尽管矛蚁属的食性极广[129]。

蚂蚁并非唯一会行军的无脊椎动物,很多狩蜂类、Polybia Lepeletier 、Angiopolybia Araujo 、也会在白蚁分飞时攻击蚁丘[130]。

寄生虫、病原体和病毒

[编辑]比起蜂类和蚂蚁,白蚁比较不会被寄生虫攻击,因为它们通常躲在蚁巢中被保护得好好的[131][132],然而,白蚁还是会被一些寄生虫攻击,如有些双翅目蝇类、Pyemotes 属的螨、和很多种线虫,这些线虫大部分为小杆目的物种[133],还有 Mermis 属、Diplogaster aerivora 、Harteria gallinarum [134]。群体可能会透过迁徙来躲避寄生虫[135]。

真菌病原体 Aspergillus nomius 和黑僵菌会威胁蚁群,因为这两种真菌并没有寄主专一性,且可以感染巢中大量的个体[136][137]。真菌透过接触传染[138]。 M. anisopliae 会削弱白蚁的免疫能力。A. nomius 只有在群体受到极大压力时才能感染个体。

可能感染白蚁的病毒包括 Entomopoxvirinae 和核多角病毒[139][140](Nuclear Polyhedrosis Virus)。

移动方式和觅食

[编辑]工蚁和兵蚁没有翅膀,而有翅型在分飞后就会把翅膀剥落,因此白蚁主要的移动方式还是靠行走[12]。

白蚁觅食的方式因种类而异,巢食共处型的会取食它们所居住的木头,而巢食连接型和巢食分离型会出巢觅食[141]。大部分的工蚁不会在外活动,也不会在没有遮蔽物的环境下觅食,它们会沿路建筑蚁道,借此保护自身[21]。鼻白蚁科会建筑蚁道来寻找食物,而找到食物的工蚁会留下费洛蒙,借此吸引更多同伴前来取食[142]。觅食的工蚁会沿路留下讯息费洛蒙,讯息费洛蒙由腹板腺分泌[143][144]。 Nasutitermes costalis 的觅食行为可分成三个阶段,第一阶段兵蚁会出外觅食,当它们找到食物时,它们会释放讯息,接收到讯息后其他兵蚁和一小群工蚁会前往食物所在地;第二阶段,食物所在地会出现大量的工蚁;第三阶段,兵蚁的数量减少,工蚁的数量增加[145]。

工蚁会随机行走(Lévy flight) 来寻找同伴或食物[146]。

竞争

[编辑]两群体间的竞争往往是透过仪式性打斗(agonistic behaviour) 进行,竞争会导致个体死亡,和领地的得失[147][148]。打斗中死去的个体可能会被集中埋起来[149]。

研究显示当属于不同群体的白蚁相遇时,有些个体会故意挡住另一方的去路,以阻止它回巢留下费洛蒙讯息,让更多工蚁前来支援[143][150]。如果陌生群体的尸体堵在探索用的隧道中,白蚁会选择另辟新路而不是移开尸体[151]。两个群体相遇时不总是会打斗,虽然它们可能会挡住对方的去路,但是不一定会打斗,如 Macrotermes bellicosus 和 Macrotermes subhyalinus 就是如此[152]。有些白蚁会自杀式的堵住道路,以防止敌人入侵,如台湾家白蚁,它们会挤进隧道里面然后死在那边,以堵塞通道进而阻止后续的打斗[153]。

在繁殖阶级中,补充繁殖型的雌虫可能会互相竞争,以抢夺繁殖地位,最后会剩下一只蚁后存活[154]。

蚂蚁和白蚁可能会互相竞争筑巢地点,特别是具有补食白蚁习性的蚂蚁,它们通常会对树栖型白蚁产生不良影响[155]。

沟通

[编辑]

大部分白蚁没有视觉,主要依靠化学分子、触觉和费洛蒙沟通,沟通内容包含觅食、寻找繁殖蚁、建筑蚁巢、分辨同伴、分飞、寻找并攻击敌人、抵御巢穴[156][143]。最频繁的沟通方式是透过触角[143]。已发现的费洛蒙有接触费洛蒙(contact pheromones)(透过交哺和清理同伴身体传播)、警戒费洛蒙、标迹费洛蒙、性费洛蒙等。警戒费洛蒙和防御性化学物质由前额腺分泌;标迹费洛蒙由腹板腺分泌;性费洛蒙由腹板腺和背板腺分泌[156]。白蚁出外觅食时会排成一列。蚁道会包覆其他物体,蚁道成分为粪便,工蚁会在蚁道中留下费洛蒙,其他个体会透过味觉受器感知费洛蒙[157]。白蚁可以透过化学讯息、震动和肢体接触来沟通[157][143]。

白蚁筑巢时使用的是间接构通。白蚁筑巢的行为是出自于个体本身的,而并非由某些个体负责发号施令。白蚁放下建材时会刺激其他白蚁放下更多建材,因此白蚁建筑与否是取决于环境,而非取决于与同伴构通的结果[143]。

白蚁透过表皮碳氢化合物来分辨同伴[158][159][160]。

防御

[编辑]

蚁巢被破坏或被入侵时白蚁会释放警戒费洛蒙,兵蚁会前往警戒费洛蒙的位置御敌[143]。白蚁警戒时会持续抽动,发出震动,有些种类兵蚁受侵扰时会从前额腺释放液体并排出含有警戒费洛蒙的粪便[143][161]。

被黑僵菌感染的个体会震动发出讯号,其他个体接收到讯号后会避开受感染的个体[162]。如果黑僵菌感染的状况极为严重,整个群体可能会因此灭亡,但发生这种状况的机率极低[163]。

有些物种的兵蚁头部前方呈截面状,受侵扰时会用头部塞住出入口,借此御敌[164],如截头堆沙白蚁(Cryptotermes domesticus )。如果出入口大于兵蚁的头部,数只兵蚁会一起挡在出入口并尝试钳咬入侵者[163]。

蚁道受破坏时会触发警戒,尽管破坏程度极低。警戒时兵蚁会聚集在破坏处,并释放警戒费洛蒙吸引更多兵蚁前来,也吸引工蚁前来修补破口[157]。警戒的白蚁会显得躁动,当它撞到另一个个体时也会让另一个体警戒,并留下警戒费洛蒙,白蚁借此来加强警戒并招募更多个体协防破口[157]。

泛热带地区的象白蚁亚科兵蚁高度特化,前额腺外突,形成象鼻状的管状结构,可透过释放化学物质来防御[165]。象鼻兵蚁大颚退化,无法自行取食,需透过工蚁喂食[166]。象白蚁亚科分泌的液体中含有多种单萜烯类[165]。同样也具有从前额腺分泌液体的还有鼻白蚁科的台湾家白蚁(Coptotermes formosanus ),台湾家白蚁分泌的液体中还有萘[167]。

Globitermes sulphureus 的兵蚁会透过自爆来防御,它们会挤破表皮底下的腺体,并放出浓稠的黄色液体,液体接触空气后会变得非常黏稠,可以困住入侵的蚂蚁或其他昆虫[168][169]。Neocapriterme taracua 也会透过自杀来防御,工蚁会挤压背部表皮下的腺体,释放出可以麻痹并杀死敌人的液体[170]。新热带的齿白蚁科也会自爆,兵蚁在通道中受攻击时会释放液体,形成路障阻止入侵者[171]。

面对尸体时工蚁会采取数种不同的策略,如掩盖尸体、吃掉尸体,还有避开尸体[172][173][174]。白蚁会把尸体带离巢穴丢弃(necrophoresis) 来避免病原体扩散[175]。处理尸体的方式取决于尸体的状态(如死亡时间)[175]。

与其他生物的交互关系

[编辑]

有一类真菌会伪装成白蚁的卵,借此避免天敌,这些真菌不会危害到白蚁的卵,有时候白蚁把这些真菌当卵照顾[176],这些真菌透过分泌葡糖苷酶来伪装成白蚁卵[177]。Trichopsenius 属的甲虫会伪装成散白蚁,这些甲虫会合成和白蚁一样的表皮碳氢化合物,借此混入蚁群中[178]。Austrospirachtha mimetes 的腹部特化膨大,让这种甲虫可以伪装成白蚁工蚁[179]。

有些蚂蚁会将白蚁制服而不是直接杀死白蚁,这样可以让白蚁保持新鲜,Formica nigra 就有这种行为[180]。有些针蚁亚科的物种会成群结队掠夺白蚁巢,有些物种则会单独行动,偷食白蚁的卵或若虫[155]。 Megaponera analis 会攻击地上的蚁冢,而矛蚁亚科则会攻击地下蚁巢[155][181]。除了敌对关系以外,有些物种也会跟白蚁和平共处,如 Nasutitermes corniger 会和某些蚂蚁形成交互关系,避免受专食白蚁的蚂蚁袭击[182]。已知最早的白蚁蚂蚁交互关系是阿兹特克蚁(Azteca)和象白蚁(Nasutitermes ),年代为渐新世至中新世[183]。

有 54 种蚂蚁被记录到居住在象白蚁废弃的或使用中的蚁巢里[184],这么多种蚂蚁会居住在象白蚁蚁巢中是因为它们的活动范围高度重叠,另外,居住在象白蚁蚁巢中可以躲避洪水[184][185]。虹琉璃蚁属也会居住在白蚁巢内,但两者之间除了掠食以外没有任何交互关系[126]。少数几种的白蚁会居住在蚂蚁巢内[186]。很多类群的无脊椎动物都是白蚁的蚁客,如某些甲虫、马陆、蝇类和蜈蚣,这些蚁客居住在白蚁群体内,离开白蚁群体便无法存活[157],有些甲虫和蝇类具有特化腺体,可分泌物质吸引白蚁照顾它们。鸟类、蜥蜴、蛇和蝎子也会居住在白蚁丘之中[157]。

有些白蚁会搬运花粉,也会频繁地访花[187],所以白蚁被认为是某些植物的授粉者[188],尤其是主要由白蚁授粉的地下兰(Rhizanthella gardneri),地下兰是唯一由白蚁授粉的兰花[187]。

很多植物具有特化的机制可以抵挡白蚁攻击,然而植物在种子阶段很脆弱,因为防御机制要等到发芽以后才会开始发育[189]。植物抵御白蚁的机制通常是在细胞壁中分泌忌避性的物质[190],这种物质可以降低白蚁分解纤维素的效率。澳洲有一种产品就是用植物萃取物做的,这种产品的使用方式是在建物的周围涂一圈以形成防护圈[190]。一种由澳洲玄参属萃取出的物质对白蚁具有忌避性[191]。研究显示白蚁会拒绝取食含有忌避性物质的食物,最后饿死,如果把白蚁和忌避物放在一起,白蚁会四处乱窜最后死亡[191]。

与环境的关系

[编辑]白蚁的数量会受到人类活动及其他因子影响。一篇研究指出人类活动越高、树木和土壤覆盖率越低、牲畜和山羊数量越多的地区,白蚁的数量越少,尤其是食木的白蚁[192]。

蚁巢

[编辑]

蚁巢可粗分为三类:地下型(完全在土中)、出土型(凸出地表)、树栖型(巢体不接触到地面,但有连接到地面的蚁道[193])。出土型蚁巢是由土壤与泥巴建筑而成[194]。蚁巢可提供适宜的居住环境并保护白蚁不受天敌捕食。大部分的蚁巢是地下型的[195]。较为原始的白蚁筑巢于木制结构中,如倒木、树桩,和活树死去的组织之中,正如同它们百万年前的祖先一般[193]。

白蚁巢主要以粪便构成,粪便是很合适的建材[196],除了粪便外,树栖型白蚁筑巢时也会加入消化过的植物组织,这种类型的巢材质类似纸板,地下白蚁则会加入泥土来筑巢和建筑蚁冢。并非所有的白蚁巢都很显眼,有些蚁巢,如热带雨林中的蚁巢便是建在地底下[195],如 Apicotermitinae 亚科[196]。居住在木头中的白蚁会在取食的同时慢慢挖出隧道并居住于其中。蚁巢和蚁冢可以让柔软的白蚁免于脱水、光照、病原菌和寄生虫,并保护白蚁不受天敌攻击[197]。树栖型蚁巢材质通常较为脆弱,因此当蚁巢受到侵袭时,白蚁会反击掠食者[198]。

红树林沼泽中的象白蚁会筑树栖巢,该巢富含木质素,且含有少量纤维素和木聚糖,这是因为象白蚁的肠道内有细菌可以帮助他们分解纤维素,而象白蚁会用粪便筑巢,并将分解后的物质一起镶入巢中。在波多黎各的红树林沼泽中,树栖型白蚁巢可占的地上总体碳含量的 2 %,这些蚁巢主要成分为部分分解的木材组织,来自于红树林树种的树干与枝条,这些树种包含 Rhizophora mangle(红树)、Avicennia germinans(黑红树)和 Laguncularia racemose(白红树[199])。

有些物种会建筑错综复杂且数量较多的巢,这种行为称作“多巢型(polycalism)”,这些散布的巢会透过地下腔室彼此连接[117]。Apicotermes 和 Trinervitermes 便是多巢型的物种[200]。建筑蚁冢的物种很少是多巢型的,而树栖型的象白蚁有少数几个物种被观察到具有多巢型的现象[200]。

蚁冢

[编辑]凸出地表的蚁巢被称作蚁冢[196],蚁冢可以提供比蚁巢更完备的庇护[198]。多雨地区的蚁冢会受到雨水侵蚀,因其材料富含黏土,而树栖型蚁巢则可忍受雨水冲打[196]。蚁冢的特定区域特别设计来抵御外敌,如 Cubitermes 会建筑狭窄的通道,通道的直径刚好可以让兵蚁堵住[201]。王室是蚁王蚁后居住的地方,其外壁非常坚硬,是蚁冢的最后一道防线[198]。

大白蚁属(Macrotermes )的某些物种可以筑出巨大的蚁冢[196],可高达 8 至 9 公尺[157]。Amitermes meridionalis 可筑出高 3 至 4 公尺,宽 2.5 公尺的蚁冢。世上最高的蚁冢位于刚果,高度为 12.8 公尺[202]。

有的蚁冢外型很特别,如磁白蚁(Amitermes),磁白蚁的蚁冢向南北延伸,外形扁平[203][204],这种蚁冢可以在清晨时快速吸收阳光提高温度,并在日正当中时避免吸收过多阳光导致过热,中午过后的温度维持稳定,直到黄昏太阳下山时[205]。

蚁道

[编辑]

白蚁会从地表往上建筑蚁道,蚁道可见于树干上或墙壁上[206]。白蚁会在夜间湿度较高的时候建筑蚁道,蚁道可以让白蚁躲避捕食者,尤其是蚂蚁[207]。蚁道内是一个高湿度且黑暗的环境,工蚁可以透过蚁道安全地抵达食物所在地[206]。蚁道是由土壤和粪便建筑而成的,颜色通常为棕色。蚁道的宽度依食物的量而定,可以小于 1 公分,也可大至好几公分宽,长度可达数十公尺[207]。

巢体类别

[编辑]- 巢食共处型 (one-piece nesting type):白蚁取食并居住在木头中,活动范围被限制在同块木头中,如木白蚁科。

- 巢食连接型 (intermediate nesting type):白蚁取食并居住在木头中,但可以于土壤中建筑蚁道,寻找其他食物资源,如鼻白蚁科。

- 巢食分离型 (separate nesting type):白蚁筑巢在土壤中,离巢觅食,如白蚁科。

与人类的关系

[编辑]作为害虫

[编辑]

很多种白蚁都可以严重损害木制结构[208]。白蚁是木材和植物组织重要的分解者,也会损害人类的木制结构,与任何包含纤维素的材料,和木质装饰品,这些人类的物品可以提供白蚁稳定的食物来源与适宜的湿度[209]。白蚁习性隐蔽,因此当人们发现木材受到白蚁蛀蚀时,往往木材内已空无一物,只剩下薄薄一层白蚁用来将自己与外界隔绝的木材[210]。目前共有 3106 种白蚁被发表,其中只有 183 种会造成危害,其中 83 种会对木质结构造成严重危害[208]。在北美洲,18 种鼻白蚁科的物种是害虫[211];在澳洲,16 种白蚁会造成经济危害;在印度次大陆,26 种白蚁被认为是害虫;热带非洲则有 24 种白蚁被认为是害虫;中美洲和西印度群岛共有 17 种白蚁是害虫[208]。在所有的白蚁害虫中,鼻白蚁科占了最大的比例,共有 28 种是害虫[208],木白蚁科只有不到一成是害虫,大多危害热带、亚热带和其他区域的木制家具和房屋结构,原白蚁科只会危害被雨水淋湿或接触到土壤的木材[208]。

木白蚁科在温带比较多,会随著受危害的木材、容器和运船进到居家环境中[208]。在寒带地区的白蚁会在温暖的房屋中栖息[212]。有些物种是入侵种,如西印度干木白蚁(Cryptotermes brevis),是世界广布的入侵种,西印度群岛中每个岛上都已被入侵,澳洲也已被入侵[213][208]。

除了建筑物以外,白蚁也会危害作物[214],白蚁通常会危害抵抗力较差的树木,而不是成长迅速的植株,白蚁常在干季危害作物及树木[214]。

在美国,因白蚁危害木制结构而造成的损失大约是每年美金 150 万元,而全世界所受到的损失难以估计[208][215]。大部分的损失是木白蚁科造成的[216]。白蚁防治的最终目的是在一开始就避免让白蚁接近木制结构和园艺作物,而不是亡羊补牢[217],所谓木制结构包含民宅或公司大楼,或任何包含木材的建物,如邮箱的木柄和电线杆。监测白蚁危害必须由专家来定期执行,因为白蚁危害的征兆较不明显,就算出现了成群的繁殖型,还是须由专家来判断来源为何。在建筑物旁边放置白蚁监测站可以监测白蚁活动,白蚁监测站由木材或其他含纤维素的材质组成。波尔多液或含铜的溶液(如铬化砷酸铜)可用来防治白蚁[218]。

人们发明了很多种方法来监测白蚁活动以防治白蚁[215]。早期有一种方法是透过含有标记蛋白 IgG 的饵来追踪,IgG 可以由兔子或鸡中萃取,投放饵料后再从野外收集白蚁并侦测是否含有 IgG 。近期成本较低的方法是用蛋白、牛奶或豆浆中的蛋白喷洒在野外的白蚁身上,后续可以用酵素结合免疫吸附分析法追踪白蚁[215]。

作为食物

[编辑]

总共有 43 种白蚁被人类当成食物或喂给牲畜[219]。白蚁在贫穷国家尤其重要,贫穷国家普遍营养不良,而白蚁富含蛋白质,取食白蚁可以补充蛋白质。世界各地都有人在吃白蚁,但直到近期已开发国家才开始流行吃白蚁[219]。

世界各地各文化中都有人会吃白蚁,在非洲的很多地方,白蚁有翅型是当地居民饮食中不可或缺的一环[220],不同地区的人有不同的方式搜集或饲养白蚁,有些会搜集兵蚁,而最难搜集的蚁后则是难得的美食[221]。白蚁有翅型富含养分、脂肪和蛋白质。当地居民认为白蚁很美味,烹煮过后味道类似坚果[220]。

在雨季初期可以搜集到白蚁的有翅型,有翅型婚飞时具有趋光性,所以当地居民会在灯上设立网子并搜集有翅型。当地居民会透过类似扬谷的方式分离白蚁和翅膀。最好的料理方法是在热盘上稍微煎过,或是炸至酥脆,料理时不需要额外放油,因为有翅型本身就含有足够的油脂。当地居民会在牲畜还没长肥或作物还没准备好收成时吃白蚁,前一季食物收获不佳时也会吃白蚁[220]。

除了非洲以外,亚洲、北美洲和南美洲的原住民也会吃白蚁。虽然澳洲土著知道白蚁可以吃,但是他们不会去吃白蚁,就算是在食物短缺的时候,目前没有多少理论试图解释这个现象[220][221]。在肯亚、塔桑尼亚、赞比亚、辛巴威和南非,蚁冢是土壤降解的主要来源[222][223][224][225]。科学家认为白蚁很适合发展为食物,或是在太空农业中占一席之地,因为白蚁富含蛋白质,所以可以将人类无法食用的农业废弃物转换成可食用的白蚁[226]。

农业

[编辑]

白蚁是农业害虫,尤其在东非和北亚最为严重(非洲作物损失率可达 3 - 100 %[227])。对抗白蚁为害可增加该地区的水渗透率,以掩没白蚁的地下隧道,借此减少地表迳流,并减少生物扰动造成的土壤侵蚀[228]。在南非,桉树、旱稻和甘蔗等作物会被白蚁严重危害,白蚁会攻击作物的叶子、根部和茎,白蚁也会攻击其他作物,如木薯、咖啡、棉花、果树、玉米、花生、黄豆和蔬菜类[229]。蚁冢会妨碍农民操作农具,然而,尽管农民厌恶蚁冢,但蚁冢通常不会造成作物产量减少[229]。白蚁也可以是农业益虫,白蚁可以让土壤更为肥沃并增加产量,白蚁和蚂蚁可以栖息于收获后未耕作残留作物残梗的农地,蚁巢可以让大量的雨水渗入地底,并增加土壤的含氮量,这两点都是农业中不可或缺的[230]。

科学和科技

[编辑]白蚁的肠道激发了科学家,科学家纷纷投入心力研发可以替代石化燃料的干净能源[231]。白蚁是高效的生物反应器,可以用一张纸生产出两公升的氢气[232]。白蚁的后肠中住了大约 200 种微生物,在白蚁消化木材和植物组织时协助分解出并释放氢气[231][233]。微生物透过目前尚未确认的酶分解木质素和纤维素,并将其分解为糖类,糖类稍后被转换成氢气。后肠内的微生物可以将糖类和氢气转换为白蚁赖以为生的醋酸纤维素[231]。科学家正尝试透过基因工程制造出可从木材中产生氢气的生物反应器[231]。

白蚁建筑复杂蚁冢的行为激发了科学家发明可以建造复杂结构的自主机器人[234],自主机器人可以独自作业,可以在轨道上移动、往高处爬和举起砖头,科学家认为自主机器人未来可以在火星计画中占一席之地,或是用来建筑防洪堤[235]。

白蚁调节蚁冢温度的方式很复杂,例如前面所提到的磁白蚁可以利用蚁冢的形状来调节温度。蚁冢升温时会产生烟囱效应,在蚁冢中产生往上的气流[236],这道气流可以促进蚁冢内的空气循环,同时从两侧引入气流。烟囱效应已经被人类应用了好几世纪,中东与近东的人会利用这个效应来降温,罗马人也会利用这个效应[237]。但直到近期这项技术才被融入现代建筑,烟囱效应尤其盛行于非洲[236]。

文化

[编辑]

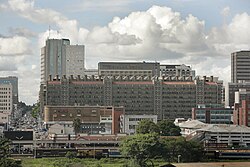

东门中心是辛巴威哈拉雷中部的购物中心和办公大楼,这栋大楼的建筑师米克·皮尔斯当初就是受白蚁的启发,才应用烟囱效应为大楼打造被动降温系统[238]。东门中心是第一栋应用白蚁降温技术的大楼,因此吸引了国际间的注意。其他应用白蚁降温技术的建筑包含东非天主教大学的学习资源中心,和澳洲墨尔本的市政厅 2 号[236]。

很少动物园会展出白蚁,因为饲养白蚁有一定的困难,且由于它们可能会变成害虫,当地机关很少会同意饲养白蚁。瑞士巴塞尔动物园有饲养白蚁,该园拥有两群状况极佳的 Macrotermes bellicosus ,在 2008 年九月,成千上万的有翅型在夜晚蜂涌而出,飞翔,死去,尸体遍布了饲养区域的地表和水池之中[239]。

一些非洲的部落拥有白蚁图腾,因此,吃白蚁在这些部落中是被禁止的[240]。白蚁是一种传统药材,用来治疗哮喘、支气管炎、嘶哑、流感、鼻窦炎、扁桃腺炎和百日咳[219]。在奈及利亚,Macrotermes nigeriensis 被当地居民用来防止鬼怪侵袭,或治疗伤口和生病的孕妇。在东南亚,白蚁被用作宗教用途,马来西亚、新加坡、泰国的民众会供奉蚁冢[241]。当地居民认为废弃的蚁冢是灵体制造的,相信其中住有保护灵(名为 Keramat 或 Datok Kong)。郊区的住民会在废弃的蚁冢上面盖红色的神龛,以祈求平安、健康和好运[241]。

白蚁轶事

[编辑]据康熙年间出版的《岭南杂记》(吴震方著)记载,公元1684年某衙门银库发现数千两银子失踪,官员们大为惊恐,到处寻找而不见,后来在墙壁下发现一些发亮的白色蛀粉,并在墙角下挖出一个白蚁窝,众官员当时不解,随后将白蚁放进炉内烧死,结果烧出了白银。

延伸阅读

[编辑]注释

[编辑]参考文献

[编辑]- ^ ?. RevBrasOrnitol: 359.

- ^ Inward D, Beccaloni G and Eggleton P. Death of an order: a comprehensive molecular phylogenetic study confirms that termites are eusocial cockroaches. Biology letters. 2007, (3): 331-335 [2020-07-04]. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2007.0102. (原始内容存档于2021-07-06).

- ^ 3.0 3.1 Weesner, F.M. Evolution and Biology of the Termites. Annual Review of Entomology. 1960, 5 (1): 153–170. doi:10.1146/annurev.en.05.010160.001101.

- ^ Evangelista, Dominic A.; Wipfler, Benjamin; Béthoux, Olivier; Donath, Alexander; Fujita, Mari; Kohli, Manpreet K.; Legendre, Frédéric; Liu, Shanlin; Machida, Ryuichiro; Misof, Bernhard; Peters, Ralph S. An integrative phylogenomic approach illuminates the evolutionary history of cockroaches and termites (Blattodea). Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2019-01-30, 286 (1895): 20182076 [2020-07-04]. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 6364590

. PMID 30963947. doi:10.1098/rspb.2018.2076. (原始内容存档于2021-04-11) (英语).

. PMID 30963947. doi:10.1098/rspb.2018.2076. (原始内容存档于2021-04-11) (英语).

- ^ Termite Biology and Ecology. Division of Technology, Industry and Economics Chemicals Branch. United Nations Environment Programme. [12 January 2015]. (原始内容存档于10 November 2014).

- ^ Claybourne, Anna. A colony of ants, and other insect groups. Chicago, Ill.: Heinemann Library. 2013: 38. ISBN 978-1-4329-6487-0.

- ^ 7.0 7.1 Engel, M.S.; Gross, M. A giant termite from the Late Miocene of Styria, Austria (Isoptera). Naturwissenschaften. 2008, 96 (2): 289–295. Bibcode:2009NW.....96..289E. PMID 19052720. doi:10.1007/s00114-008-0480-y.

- ^ Heidecker, J.L.; Leuthold, R.H. The organisation of collective foraging in the harvester termite Hodotermes mossambicus (Isoptera). Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 1984, 14 (3): 195–202. doi:10.1007/BF00299619.

- ^ Costa-Leonardo, A.M.; Haifig, I. Pheromones and exocrine glands in Isoptera. Vitamins and Hormones. 2010, 83: 521–549. ISBN 9780123815163. PMID 20831960. doi:10.1016/S0083-6729(10)83021-3.

- ^ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Bignell, Roisin & Lo 2010,第7页.

- ^ Bignell, Roisin & Lo 2010,第7–9页.

- ^ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 Bignell, Roisin & Lo 2010,第11页.

- ^ Robinson, W.H. Urban Insects and Arachnids: A Handbook of Urban Entomology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2005: 291. ISBN 978-1-139-44347-0.

- ^ Riparbelli, M.G; Dallai, R; Mercati, D; Bu, Y; Callaini, G. Centriole symmetry: a big tale from small organisms. Cell Motility and the Cytoskeleton. 2009, 66 (12): 1100–5. PMID 19746415. doi:10.1002/cm.20417.

- ^ Nalepa, C.A.; Lenz, M. The ootheca of Mastotermes darwiniensis Froggatt (Isoptera: Mastotermitidae): homology with cockroach oothecae. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2000, 267 (1454): 1809–1813. PMC 1690738

. PMID 12233781. doi:10.1098/rspb.2000.1214.

. PMID 12233781. doi:10.1098/rspb.2000.1214.

- ^ Crosland, M.W.J.; Su, N.Y.; Scheffrahn, R.H. Arolia in termites (Isoptera): functional significance and evolutionary loss. Insectes Sociaux. 2005, 52 (1): 63–66. doi:10.1007/s00040-004-0779-4.

- ^ Cranshaw, W. 11. Bugs Rule!: An Introduction to the World of Insects. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. 2013: 188. ISBN 978-0-691-12495-7.

- ^ Bignell, Roisin & Lo 2010,第9页.

- ^ Bignell, Roisin & Lo 2010,第10页.

- ^ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 20.4 20.5 20.6 Termites. Australian Museum. [8 January 2015]. (原始内容存档于2015-01-08).

- ^ 21.0 21.1 Bignell, Roisin & Lo 2010,第13页.

- ^ Machida, M.; Kitade, O.; Miura, T.; Matsumoto, T. Nitrogen recycling through proctodeal trophallaxis in the Japanese damp-wood termite Hodotermopsis japonica (Isoptera, Termopsidae). Insectes Sociaux. 2001, 48 (1): 52–56. ISSN 1420-9098. doi:10.1007/PL00001745.

- ^ Higashi, Masahiko; Yamamura, Norio; Abe, Takuya; Burns, Thomas P. Why don't all termite species have a sterile worker caste?. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 1991-10-22, 246 (1315): 25–29. ISSN 0962-8452. PMID 1684665. doi:10.1098/rspb.1991.0120 (英语).

- ^ 24.0 24.1 24.2 Bignell, Roisin & Lo 2010,第18页.

- ^ Krishna, K. Termite. Encyclopædia Britannica. [11 September 2015]. (原始内容存档于2021-04-21).

- ^ Busvine, J.R. Insects and Hygiene The biology and control of insect pests of medical and domestic importance 3rd. Boston, MA: Springer US. 2013: 545. ISBN 978-1-4899-3198-6.

- ^ Meek, S.P. Termite Control at an Ordnance Storage Depot. American Defense Preparedness Association. 1934: 159.

- ^ Prestwich, G.D. From tetracycles to macrocycles. Tetrahedron. 1982, 38 (13): 1911–1919. doi:10.1016/0040-4020(82)80040-9.

- ^ Prestwich, G. D.; Bentley, B.L.; Carpenter, E.J. Nitrogen sources for neotropical nasute termites: Fixation and selective foraging. Oecologia. 1980, 46 (3): 397–401. Bibcode:1980Oecol..46..397P. ISSN 1432-1939. PMID 28310050. doi:10.1007/BF00346270.

- ^ Thorne, B. L.; Breisch, N. L.; Muscedere, M. L. Evolution of eusociality and the soldier caste in termites: Influence of intraspecific competition and accelerated inheritance. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2003-10-28, 100 (22): 12808–12813. Bibcode:2003PNAS..10012808T. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 240700

. PMID 14555764. doi:10.1073/pnas.2133530100 (英语).

. PMID 14555764. doi:10.1073/pnas.2133530100 (英语).

- ^ 31.0 31.1 31.2 Horwood, M.A.; Eldridge, R.H. Termites in New South Wales Part 1. Termite biology (PDF) (技术报告). Forest Resources Research. 2005 [2020-07-04]. ISSN 0155-7548. 96-38. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2021-02-27).

- ^ 32.0 32.1 Keller, L. Queen lifespan and colony characteristics in ants and termites. Insectes Sociaux. 1998, 45 (3): 235–246. doi:10.1007/s000400050084.

- ^ 周羿彣. 全台爆發大水蟻!網期待「要下雨了嗎」 鄭明典也想問專家. 三立新闻网. [2021-05-07]. (原始内容存档于2021-12-09) (中文).

- ^ Cranshaw, W. 11. Bugs Rule!: An Introduction to the World of Insects. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. 2013: 188. ISBN 978-0-691-12495-7.

- ^ Termite. Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. [5 January 2015]. (原始内容存档于2021-04-11).

- ^ 36.0 36.1 Harper, Douglas. Termite. Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ Lobeck, A. Kohl. Geomorphology; an Introduction to the Study of Landscapes 1st. University of California: McGraw Hill Book Company, Incorporated. 1939: 431–432. ASIN B002P5O9SC.

- ^ Cleveland, L.R.; Hall, S.K.; Sanders, E.P.; Collier, J. The Wood-Feeding Roach Cryptocercus, its protozoa, and the symbiosis between protozoa and roach. Memoirs of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. 1934, 17 (2): 185–382. doi:10.1093/aesa/28.2.216.

- ^ McKittrick, F.A. A contribution to the understanding of cockroach-termite affinities.. Annals of the Entomological Society of America. 1965, 58 (1): 18–22. PMID 5834489. doi:10.1093/aesa/58.1.18.

- ^ Ware, J.L.; Litman, J.; Klass, K.-D.; Spearman, L.A. Relationships among the major lineages of Dictyoptera: the effect of outgroup selection on dictyopteran tree topology. Systematic Entomology. 2008, 33 (3): 429–450. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3113.2008.00424.x.

- ^ 41.0 41.1 Inward, D.; Beccaloni, G.; Eggleton, P. Death of an order: a comprehensive molecular phylogenetic study confirms that termites are eusocial cockroaches.. Biology Letters. 2007, 3 (3): 331–5. PMC 2464702

. PMID 17412673. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2007.0102.

. PMID 17412673. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2007.0102.

- ^ Eggleton, P.; Beccaloni, G.; Inward, D. Response to Lo et al.. Biology Letters. 2007, 3 (5): 564–565. PMC 2391203

. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2007.0367.

. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2007.0367.

- ^ Ohkuma, M.; Noda, S.; Hongoh, Y.; Nalepa, C.A.; Inoue, T. Inheritance and diversification of symbiotic trichonymphid flagellates from a common ancestor of termites and the cockroach Cryptocercus. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2009, 276 (1655): 239–245. PMC 2674353

. PMID 18812290. doi:10.1098/rspb.2008.1094.

. PMID 18812290. doi:10.1098/rspb.2008.1094.

- ^ Lo, N.; Tokuda, G.; Watanabe, H.; Rose, H.; Slaytor, M.; Maekawa, K.; Bandi, C.; Noda, H. Evidence from multiple gene sequences indicates that termites evolved from wood-feeding cockroaches. Current Biology. June 2000, 10 (13): 801–814. PMID 10898984. doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(00)00561-3.

- ^ Grimaldi, D.; Engel, M.S. Evolution of the insects 1st. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2005: 237. ISBN 978-0-521-82149-0.

- ^ Klass, K.D.; Nalepa, C.; Lo, N. Wood-feeding cockroaches as models for termite evolution (Insecta: Dictyoptera): Cryptocercus vs. Parasphaeria boleiriana. Molecular Phylogenetics & Evolution. 2008, 46 (3): 809–817. PMID 18226554. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2007.11.028.

- ^ Lo, N.; Engel, M.S.; Cameron, S.; Nalepa, C.A.; Tokuda, G.; Grimaldi, D.; Kitade, O..; Krishna, K.; Klass, K.-D.; Maekawa, K.; Miura, T.; Thompson, G.J. Comment. Save Isoptera: a comment on Inward et al.. Biology Letters. 2007, 3 (5): 562–563. PMC 2391185

. PMID 17698448. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2007.0264.

. PMID 17698448. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2007.0264.

- ^ Costa, James. The other insect societies. Harvard University Press. 2006: 135–136. ISBN 978-0-674-02163-1.

- ^ Capinera, J.L. Encyclopedia of Entomology 2nd. Dordrecht: Springer. 2008: 3033–3037, 3754. ISBN 978-1-4020-6242-1.

- ^ Vrsanky, P.; Aristov, D. Termites (Isoptera) from the Jurassic/Cretaceous boundary: Evidence for the longevity of their earliest genera. European Journal of Entomology. 2014, 111 (1): 137–141. doi:10.14411/eje.2014.014.

- ^ Poinar, G.O. Description of an early Cretaceous termite (Isoptera: Kalotermitidae) and its associated intestinal protozoa, with comments on their co-evolution. Parasites & Vectors. 2009, 2 (1–17): 12. PMC 2669471

. PMID 19226475. doi:10.1186/1756-3305-2-12.

. PMID 19226475. doi:10.1186/1756-3305-2-12.

- ^ Legendre, F.; Nel, A.; Svenson, G.J.; Robillard, T.; Pellens, R.; Grandcolas, P.; Escriva, H. Phylogeny of Dictyoptera: Dating the Origin of Cockroaches, Praying Mantises and Termites with Molecular Data and Controlled Fossil Evidence. PLoS ONE. 2015, 10 (7): e0130127. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1030127L. PMC 4511787

. PMID 26200914. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0130127.

. PMID 26200914. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0130127.

- ^ Luo, Z.X.; Wible, J.R. A Late Jurassic digging mammal and early mammalian diversification.. Science. 2005, 308 (5718): 103–107. Bibcode:2005Sci...308..103L. PMID 15802602. doi:10.1126/science.1108875.

- ^ Rohr, D.M.; Boucot, A. J.; Miller, J.; Abbott, M. Oldest termite nest from the Upper Cretaceous of west Texas. Geology. 1986, 14 (1): 87. Bibcode:1986Geo....14...87R. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(1986)14<87:OTNFTU>2.0.CO;2.

- ^ 55.0 55.1 Tilyard, R.J. Kansas Permian insects. Part XX the cockroaches, or order Blattaria. American Journal of Science. 1937, 34 (201): 169–202, 249–276. Bibcode:1937AmJS...34..169T. doi:10.2475/ajs.s5-34.201.169.

- ^ Henry, M.S. Symbiosis: Associations of Invertebrates, Birds, Ruminants, and Other Biota. New York, New York: Elsevier. 2013: 59. ISBN 978-1-4832-7592-5.

- ^ 57.0 57.1 Krishna, K.; Grimaldi, D.A.; Krishna, V.; Engel, M.S. Treatise on the Isoptera of the world (PDF). Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 1. 2013, 377 (7): 1–200 [2020-07-04]. doi:10.1206/377.1. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2021-04-11).

- ^ Evangelista, Dominic A.; Wipfler, Benjamin; Béthoux, Olivier; Donath, Alexander; Fujita, Mari; Kohli, Manpreet K.; Legendre, Frédéric; Liu, Shanlin; Machida, Ryuichiro; Misof, Bernhard; Peters, Ralph S. An integrative phylogenomic approach illuminates the evolutionary history of cockroaches and termites (Blattodea). Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2019-01-30, 286 (1895): 20182076 [2020-07-04]. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 6364590

. PMID 30963947. doi:10.1098/rspb.2018.2076. (原始内容存档于2021-04-11) (英语).

. PMID 30963947. doi:10.1098/rspb.2018.2076. (原始内容存档于2021-04-11) (英语).

- ^ Bell, W.J.; Roth, L.M.; Nalepa, C.A. Cockroaches: ecology, behavior, and natural history. Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press. 2007: 161. ISBN 978-0-8018-8616-4.

- ^ Engel, M. Family-group names for termites (Isoptera), redux. ZooKeys. 2011, (148): 171–184. PMC 3264418

. PMID 22287896. doi:10.3897/zookeys.148.1682.

. PMID 22287896. doi:10.3897/zookeys.148.1682.

- ^ Thorne, Barbara L. Evolution of eusociality in termites (PDF). Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 1997, 28 (5): 27–53. PMC 349550

. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.28.1.27. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2010-05-30).

. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.28.1.27. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2010-05-30).

- ^ 62.0 62.1 Harrison, Mark C.; Jongepier, Evelien; Robertson, Hugh M.; Arning, Nicolas; Bitard-Feildel, Tristan; Chao, Hsu; Childers, Christopher P.; Dinh, Huyen; Doddapaneni, Harshavardhan; Dugan, Shannon; Gowin, Johannes; Greiner, Carolin; Han, Yi; Hu, Haofu; Hughes, Daniel S. T.; Huylmans, Ann-Kathrin; Kemena, Carsten; Kremer, Lukas P. M.; Lee, Sandra L.; Lopez-Ezquerra, Alberto; Mallet, Ludovic; Monroy-Kuhn, Jose M.; Moser, Annabell; Murali, Shwetha C.; Muzny, Donna M.; Otani, Saria; Piulachs, Maria-Dolors; Poelchau, Monica; Qu, Jiaxin; Schaub, Florentine; Wada-Katsumata, Ayako; Worley, Kim C.; Xie, Qiaolin; Ylla, Guillem; Poulsen, Michael; Gibbs, Richard A.; Schal, Coby; Richards, Stephen; Belles, Xavier; Korb, Judith; Bornberg-Bauer, Erich. Hemimetabolous genomes reveal molecular basis of termite eusociality. Nature Ecology & Evolution. 2018, 2 (3): 557–566. PMC 6482461

. PMID 29403074. doi:10.1038/s41559-017-0459-1.

. PMID 29403074. doi:10.1038/s41559-017-0459-1.

- ^ Termites had first castes. Nature. 2016, 530 (7590): 256. Bibcode:2016Natur.530Q.256.. doi:10.1038/530256a.

- ^ Terrapon, Nicolas; Li, Cai; Robertson, Hugh M.; Ji, Lu; Meng, Xuehong; Booth, Warren; Chen, Zhensheng; Childers, Christopher P.; Glastad, Karl M.; Gokhale, Kaustubh; et al. Molecular traces of alternative social organization in a termite genome. Nature Communications. 2014, 5: 3636. Bibcode:2014NatCo...5.3636T. PMID 24845553. doi:10.1038/ncomms4636.

- ^ Poulsen, Michael; Hu, Haofu; Li, Cai; Chen, Zhensheng; Xu, Luohao; Otani, Saria; Nygaard, Sanne; Nobre, Tania; Klaubauf, Sylvia; Schindler, Philipp M .; et al. Complementary symbiont contributions to plant decomposition in a fungus-farming termite. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2014, 111 (40): 14500–14505. Bibcode:2014PNAS..11114500P. PMC 4209977

. PMID 25246537. doi:10.1073/pnas.1319718111.

. PMID 25246537. doi:10.1073/pnas.1319718111.

- ^ Kohler, T; Dietrich, C; Scheffrahn, RH; Brune, A. High‐resolution analysis of gut environment and bacterial microbiota reveals functional compartmentation of the gut in wood‐feeding higher termites (Nasutitermes spp.). Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2012, 78 (13): 4691–4701. PMC 3370480

. PMID 22544239. doi:10.1128/aem.00683-12.

. PMID 22544239. doi:10.1128/aem.00683-12.

- ^ 67.0 67.1 67.2 67.3 Termite Biology and Ecology. Division of Technology, Industry and Economics Chemicals Branch. United Nations Environment Programme. [12 January 2015]. (原始内容存档于10 November 2014).

- ^ Meyer, V.W.; Braack, L.E.O.; Biggs, H.C.; Ebersohn, C. Distribution and density of termite mounds in the northern Kruger National Park, with specific reference to those constructed by Macrotermes Holmgren (Isoptera: Termitidae). African Entomology. 1999, 7 (1): 123–130.

- ^ Sanderson, M.G. Biomass of termites and their emissions of methane and carbon dioxide: A global database. Global Biogeochemical Cycles. 1996, 10 (4): 543–557. Bibcode:1996GBioC..10..543S. doi:10.1029/96GB01893.

- ^ Heather, N.W. The exotic drywood termite Cryptotermes brevis (Walker) (Isoptera : Kalotermitidae) and endemic Australian drywood termites in Queensland. Australian Journal of Entomology. 1971, 10 (2): 134–141. doi:10.1111/j.1440-6055.1971.tb00022.x.

- ^ Korb, J. Termites, hemimetabolous diploid white ants?. Frontiers in Zoology. 2008, 5 (1): 15. PMC 2564920

. PMID 18822181. doi:10.1186/1742-9994-5-15.

. PMID 18822181. doi:10.1186/1742-9994-5-15.

- ^ Davis, P. Termite Identification. Entomology at Western Australian Department of Agriculture. (原始内容存档于2009-06-12).

- ^ Neoh, K.B.; Lee, C.Y. Developmental stages and caste composition of a mature and incipient colony of the drywood termite, Cryptotermes dudleyi (Isoptera: Kalotermitidae). Journal of Economic Entomology. 2011, 104 (2): 622–8. PMID 21510214. doi:10.1603/ec10346.

- ^ 74.0 74.1 Native subterranean termites. University of Florida. [8 January 2015]. (原始内容存档于2021-04-11).

- ^ 75.0 75.1 Schneider, M.F. Termite Life Cycle and Caste System. University of Freiburg. 1999 [8 January 2015]. (原始内容存档于2021-04-11).

- ^ Simpson, S.J.; Sword, G.A.; Lo, N. Polyphenism in Insects. Current Biology. 2011, 21 (18): 738–749. PMID 21959164. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2011.06.006.

- ^ 77.0 77.1 Tasaki E, Kobayashi K, Matsuura K, Iuchi Y. An Efficient Antioxidant System in a Long-Lived Termite Queen. PLoS ONE. 2017, 12 (1): e0167412. Bibcode:2017PLoSO..1267412T. PMC 5226355

. PMID 28076409. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0167412.

. PMID 28076409. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0167412.

- ^ 78.0 78.1 Miller, D.M. Subterranean Termite Biology and Behavior. Virginia Tech (Virginia State University). 5 March 2010 [8 January 2015]. (原始内容存档于2021-04-11).

- ^ 79.0 79.1 Gouge, D.H.; Smith, K.A.; Olson, C.; Baker, P. Drywood Termites. Cooperative Extension, College of Agriculture & Life Sciences. University of Arizona. 2001 [16 September 2015]. (原始内容存档于2016-11-10).

- ^ Kaib, M.; Hacker, M.; Brandl, R. Egg-laying in monogynous and polygynous colonies of the termite Macrotermes michaelseni (Isoptera, Macrotermitidae). Insectes Sociaux. 2001, 48 (3): 231–237. doi:10.1007/PL00001771.

- ^ Gilbert, executive editors, G.A. Kerkut, L.I. Comprehensive insect physiology, biochemistry, and pharmacology 1st. Oxford: Pergamon Press. 1985: 167. ISBN 978-0-08-026850-7.

- ^ Wyatt, T.D. Pheromones and animal behaviour: communication by smell and taste

Repr. with corrections 2004. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2003: 119. ISBN 978-0-521-48526-5.

Repr. with corrections 2004. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2003: 119. ISBN 978-0-521-48526-5.

- ^ Morrow, E.H. How the sperm lost its tail: the evolution of aflagellate sperm.. Biological Reviews of the Cambridge Philosophical Society. 2004, 79 (4): 795–814. PMID 15682871. doi:10.1017/S1464793104006451.

- ^ Supplementary reproductive. University of Hawaii. [16 September 2015]. (原始内容存档于30 October 2014).

- ^ Yashiro, T.; Matsuura, K. Termite queens close the sperm gates of eggs to switch from sexual to asexual reproduction. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2014, 111 (48): 17212–17217. Bibcode:2014PNAS..11117212Y. PMC 4260566

. PMID 25404335. doi:10.1073/pnas.1412481111.

. PMID 25404335. doi:10.1073/pnas.1412481111.

- ^ Matsuura, K.; Vargo, E.L.; Kawatsu, K.; Labadie, P. E.; Nakano, H.; Yashiro, T.; Tsuji, K. Queen Succession Through Asexual Reproduction in Termites. Science. 2009, 323 (5922): 1687. Bibcode:2009Sci...323.1687M. PMID 19325106. doi:10.1126/science.1169702.

- ^ Fougeyrollas R, Dolejšová K, Sillam-Dussès D, Roy V, Poteaux C, Hanus R, Roisin Y. Asexual queen succession in the higher termite Embiratermes neotenicus. Proc. Biol. Sci. June 2015, 282 (1809): 20150260. PMC 4590441

. PMID 26019158. doi:10.1098/rspb.2015.0260.

. PMID 26019158. doi:10.1098/rspb.2015.0260.

- ^ Freymann, B.P.; Buitenwerf, R.; Desouza, O.; Olff. The importance of termites (Isoptera) for the recycling of herbivore dung in tropical ecosystems: a review. European Journal of Entomology. 2008, 105 (2): 165–173. doi:10.14411/eje.2008.025.

- ^ de Souza, O.F.; Brown, V.K. Effects of habitat fragmentation on Amazonian termite communities. Journal of Tropical Ecology. 2009, 10 (2): 197–206. doi:10.1017/S0266467400007847.

- ^ Bignell, Roisin & Lo 2010,第13–14页.

- ^ Tokuda, G.; Watanabe, H.; Matsumoto, T.; Noda, H. Cellulose digestion in the wood-eating higher termite, Nasutitermes takasagoensis (Shiraki): distribution of cellulases and properties of endo-beta-1,4-glucanase.. Zoological Science. 1997, 14 (1): 83–93. PMID 9200983. doi:10.2108/zsj.14.83.

- ^ Ritter, Michael. The Physical Environment: an Introduction to Physical Geography. University of Wisconsin. 2006: 450. (原始内容存档于18 May 2007).

- ^ Ikeda-Ohtsubo, W.; Brune, A. Cospeciation of termite gut flagellates and their bacterial endosymbionts: Trichonympha species and Candidatus Endomicrobium trichonymphae. Molecular Ecology. 2009, 18 (2): 332–342. PMID 19192183. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2008.04029.x.

- ^ Slaytor, M. Cellulose digestion in termites and cockroaches: What role do symbionts play?. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology B. 1992, 103 (4): 775–784. doi:10.1016/0305-0491(92)90194-V.

- ^ Watanabe, H..; Noda, H.; Tokuda, G.; Lo, N. A cellulase gene of termite origin. Nature. 1998, 394 (6691): 330–331. Bibcode:1998Natur.394..330W. PMID 9690469. doi:10.1038/28527.

- ^ Tokuda, G.; Watanabe, H. Hidden cellulases in termites: revision of an old hypothesis. Biology Letters. 2007, 3 (3): 336–339. PMC 2464699

. PMID 17374589. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2007.0073.

. PMID 17374589. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2007.0073.

- ^ Li, Z.-Q.; Liu, B.-R.; Zeng, W.-H.; Xiao, W.-L.; Li, Q.-J.; Zhong, J.-H. Character of Cellulase Activity in the Guts of Flagellate-Free Termites with Different Feeding Habits. Journal of Insect Science. 2013, 13 (37): 37. PMC 3738099

. PMID 23895662. doi:10.1673/031.013.3701.

. PMID 23895662. doi:10.1673/031.013.3701.

- ^ Dietrich, C.; Kohler, T.; Brune, A. The Cockroach origin of the termite gut microbiota: patterns in bacterial community structure reflect major evolutionary events. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2014, 80 (7): 2261–2269. PMC 3993134

. PMID 24487532. doi:10.1128/AEM.04206-13.

. PMID 24487532. doi:10.1128/AEM.04206-13.

- ^ Allen, C.T.; Foster, D.E.; Ueckert, D.N. Seasonal Food Habits of a Desert Termite, Gnathamitermes tubiformans, in West Texas. Environmental Entomology. 1980, 9 (4): 461–466. doi:10.1093/ee/9.4.461.

- ^ McMahan, E.A. Studies of Termite Wood-feeding Preferences (PDF). Hawaiian Entomological Society. 1966, 19 (2): 239–250 [2020-07-04]. ISSN 0073-134X. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2021-04-11).

- ^ Aanen, D.K.; Eggleton, P.; Rouland-Lefevre, C.; Guldberg-Froslev, T.; Rosendahl, S.; Boomsma, J.J. The evolution of fungus-growing termites and their mutualistic fungal symbionts. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2002, 99 (23): 14887–14892. Bibcode:2002PNAS...9914887A. JSTOR 3073687. PMC 137514

. PMID 12386341. doi:10.1073/pnas.222313099.

. PMID 12386341. doi:10.1073/pnas.222313099.

- ^ Mueller, U.G.; Gerardo, N. Fungus-farming insects: Multiple origins and diverse evolutionary histories. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2002, 99 (24): 15247–15249. Bibcode:2002PNAS...9915247M. PMC 137700

. PMID 12438688. doi:10.1073/pnas.242594799.

. PMID 12438688. doi:10.1073/pnas.242594799.

- ^ Roberts, E.M.; Todd, C.N.; Aanen, D.K.; Nobre, T.; Hilbert-Wolf, H.L.; O'Connor, P.M.; Tapanila, L.; Mtelela, C.; Stevens, N.J. Oligocene termite nests with in situ fungus gardens from the Rukwa Rift Basin, Tanzania, support a paleogene African origin for insect agriculture. PLoS ONE. 2016, 11 (6): e0156847. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1156847R. PMC 4917219

. PMID 27333288. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0156847.

. PMID 27333288. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0156847.

- ^ Radek, R. Flagellates, bacteria, and fungi associated with termites: diversity and function in nutrition – a review (PDF). Ecotropica. 1999, 5: 183–196 [2020-07-04]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2021-04-11).

- ^ Breznak, J.A.; Brune, A. Role of microorganisms in the digestion of lignocellulose by termites. Annual Review of Entomology. 1993, 39 (1): 453–487. doi:10.1146/annurev.en.39.010194.002321.

- ^ Parabasalia. Archibald. Springer, Cham. 2016. ISBN 978-3-319-32669-6. Authors list列表中的

|first1=缺少|last1=(帮助) - ^ Chun-I Chiu, Jie-Hao Ou, Chi-Yu Chen & Hou-Feng Li. Fungal nutrition allocation enhances mutualism with fungus-growing termite. Fungal Ecology. 2019, (41): 92-100 [2020-03-04]. doi:10.1016/j.funeco.2019.04.001. (原始内容存档于2021-04-11).

- ^ Kok, O.B.; Hewitt, P.H. Bird and mammal predators of the harvester termite Hodotermes mossambicus (Hagen) in semi-arid regions of South Africa. South African Journal of Science. 1990, 86 (1): 34–37. ISSN 0038-2353.

- ^ 109.0 109.1 109.2 109.3 109.4 Hölldobler, B.; Wilson, E.O. The Ants. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. 1990: 559–566. ISBN 978-0-674-04075-5.

- ^ 110.0 110.1 Culliney, T.W.; Grace, J.K. Prospects for the biological control of subterranean termites (Isoptera: Rhinotermitidae), with special reference to Coptotermes formosanus. Bulletin of Entomological Research. 2000, 90 (1): 9–21. PMID 10948359. doi:10.1017/S0007485300000663.

- ^ Dean, W.R.J.; Milton, S.J. Plant and invertebrate assemblages on old fields in the arid southern Karoo, South Africa. African Journal of Ecology. 1995, 33 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2028.1995.tb00777.x.

- ^ Wade, W.W. Ecology of Desert Systems. Burlington: Elsevier. 2002: 216. ISBN 978-0-08-050499-5.

- ^ Reagan, D.P.; Waide, R.B. The food web of a tropical rain forest. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 1996: 294. ISBN 978-0-226-70599-6.

- ^ 114.0 114.1 Bardgett, R.D.; Herrick, J.E.; Six, J.; Jones, T.H.; Strong, D.R.; van der Putten, W.H. Soil ecology and ecosystem services 1st. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2013: 178. ISBN 978-0-19-968816-6.

- ^ Choe, J.C.; Crespi, B.J. The evolution of social behavior in insects and arachnids 1st. Cambridge: Cambridge university press. 1997: 76. ISBN 978-0-521-58977-2.

- ^ Bignell, Roisin & Lo 2010,第509页.

- ^ 117.0 117.1 117.2 Abe, Y.; Bignell, D.E.; Higashi, T. Termites: Evolution, Sociality, Symbioses, Ecology. Springer. 2014: 124–149. ISBN 978-94-017-3223-9. doi:10.1007/978-94-017-3223-9.

- ^ Wilson, D.S.; Clark, A.B. Above ground defence in the harvester termite, Hodotermes mossambicus. Journal of the Entomological Society of South Africa. 1977, 40: 271–282.

- ^ Lavelle, P.; Spain, A.V. Soil ecology 2nd. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic. 2001: 316. ISBN 978-0-306-48162-8.

- ^ Richardson, P.K.R.; Bearder, S.K. The Hyena Family

. MacDonald, D. (编). The Encyclopedia of Mammals. New York, NY: Facts on File Publication: 158–159. 1984. ISBN 978-0-87196-871-5.

. MacDonald, D. (编). The Encyclopedia of Mammals. New York, NY: Facts on File Publication: 158–159. 1984. ISBN 978-0-87196-871-5.

- ^ Mills, G.; Harvey, M. African Predators. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press. 2001: 71. ISBN 978-1-56098-096-4.

- ^ d'Errico, F.; Backwell, L. Assessing the function of early hominin bone tools. Journal of Archaeological Science. 2009, 36 (8): 1764–1773. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2009.04.005.

- ^ Lepage, M.G. Étude de la prédation de Megaponera foetens (F.) sur les populations récoltantes de Macrotermitinae dans un ecosystème semi-aride (Kajiado-Kenya). Insectes Sociaux. 1981, 28 (3): 247–262. doi:10.1007/BF02223627 (西班牙语).

- ^ Levieux, J. Note préliminaire sur les colonnes de chasse de Megaponera fœtens F. (Hyménoptère Formicidæ). Insectes Sociaux. 1966, 13 (2): 117–126. doi:10.1007/BF02223567 (法语).

- ^ Longhurst, C.; Baker, R.; Howse, P.E. Chemical crypsis in predatory ants. Experientia. 1979, 35 (7): 870–872. doi:10.1007/BF01955119.

- ^ 126.0 126.1 Wheeler, W.M. Ecological relations of Ponerine and other ants to termites. Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. 1936, 71 (3): 159–171 [2020-07-04]. JSTOR 20023221. doi:10.2307/20023221. (原始内容存档于2021-04-11).

- ^ Shattuck, S.O.; Heterick, B.E. Revision of the ant genus Iridomyrmex (Hymenoptera : Formicidae) (PDF). Zootaxa. 2011, 2845: 1–74 [2020-07-04]. ISBN 978-1-86977-676-3. ISSN 1175-5334. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2021-03-15).

- ^ Traniello, J.F.A. Enemy deterrence in the recruitment strategy of a termite: Soldier-organized foraging in Nasutitermes costalis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1981, 78 (3): 1976–1979. Bibcode:1981PNAS...78.1976T. PMC 319259

. PMID 16592995. doi:10.1073/pnas.78.3.1976.

. PMID 16592995. doi:10.1073/pnas.78.3.1976.

- ^ Schöning, C.; Moffett, M.W. Driver Ants Invading a Termite Nest: why do the most catholic predators of all seldom take this abundant prey? (PDF). Biotropica. 2007, 39 (5): 663–667 [2020-07-04]. doi:10.1111/j.1744-7429.2007.00296.x. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2015-11-12).

- ^ Mill, A.E. Observations on Brazilian termite alate swarms and some structures used in the dispersal of reproductives (Isoptera: Termitidae). Journal of Natural History. 1983, 17 (3): 309–320. doi:10.1080/00222938300770231.

- ^ Schmid-Hempel 1998,第61页.

- ^ Schmid-Hempel 1998,第75页.

- ^ Schmid-Hempel 1998,第59页.

- ^ Schmid-Hempel 1998,第301–302页.

- ^ Schmid-Hempel 1998,第19页.

- ^ Weiser, J.; Hrdy, I. Pyemotes – mites as parasites of termites. Zeitschrift für Angewandte Entomologie. 2009, 51 (1–4): 94–97. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0418.1962.tb04062.x.

- ^ Chouvenc, T.; Efstathion, C.A.; Elliott, M.L.; Su, N.Y. Resource competition between two fungal parasites in subterranean termites.. Die Naturwissenschaften. 2012, 99 (11): 949–58. Bibcode:2012NW.....99..949C. PMID 23086391. doi:10.1007/s00114-012-0977-2.

- ^ Schmid-Hempel 1998,第38, 102页.

- ^ Chouvenc, T.; Mullins, A.J.; Efstathion, C.A.; Su, N.-Y. Virus-like symptoms in a termite (Isoptera: Kalotermitidae) field colony. Florida Entomologist. 2013, 96 (4): 1612–1614. doi:10.1653/024.096.0450.

- ^ Al Fazairy, A.A.; Hassan, F.A. Infection of Termites by Spodoptera littoralis Nuclear Polyhedrosis Virus. International Journal of Tropical Insect Science. 2011, 9 (1): 37–39. doi:10.1017/S1742758400009991.

- ^ Traniello, J.F.A.; Leuthold, R.H. Behavior and Ecology of Foraging in Termites. Springer Netherlands. 2000: 141–168. ISBN 978-94-017-3223-9. doi:10.1007/978-94-017-3223-9_7.

- ^ Reinhard, J.; Kaib, M. Trail communication during foraging and recruitment in the subterranean termite Reticulitermes santonensis De Feytaud (Isoptera, Rhinotermitidae). Journal of Insect Behavior. 2001, 14 (2): 157–171. doi:10.1023/A:1007881510237.

- ^ 143.0 143.1 143.2 143.3 143.4 143.5 143.6 143.7 Costa-Leonardo, A.M.; Haifig, I. Termite communication during different behavioral activities in Biocommunication of Animals. Springer Netherlands. 2013: 161–190. ISBN 978-94-007-7413-1. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-7414-8_10.

- ^ Costa-Leonardo, A.M. Morphology of the sternal gland in workers of Coptotermes gestroi (Isoptera, Rhinotermitidae).. Micron. 2006, 37 (6): 551–556. PMID 16458523. doi:10.1016/j.micron.2005.12.006.

- ^ Traniello, J.F.; Busher, C. Chemical regulation of polyethism during foraging in the neotropical termite Nasutitermes costalis. Journal of Chemical Ecology. 1985, 11 (3): 319–32. PMID 24309963. doi:10.1007/BF01411418.

- ^ Miramontes, O.; DeSouza, O.; Paiva, L.R.; Marins, A.; Orozco, S.; Aegerter, C.M. Lévy flights and self-similar exploratory behaviour of termite workers: beyond model fitting. PLoS ONE. 2014, 9 (10): e111183. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9k1183M. PMC 4213025

. PMID 25353958. arXiv:1410.0930

. PMID 25353958. arXiv:1410.0930  . doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0111183.

. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0111183.

- ^ Jost, C.; Haifig, I.; de Camargo-Dietrich, C.R.R.; Costa-Leonardo, A.M. A comparative tunnelling network approach to assess interspecific competition effects in termites. Insectes Sociaux. 2012, 59 (3): 369–379. doi:10.1007/s00040-012-0229-7.

- ^ Polizzi, J.M.; Forschler, B.T. Intra- and interspecific agonism in Reticulitermes flavipes (Kollar) and R. virginicus (Banks) and effects of arena and group size in laboratory assays. Insectes Sociaux. 1998, 45 (1): 43–49. doi:10.1007/s000400050067.

- ^ Darlington, J.P.E.C. The underground passages and storage pits used in foraging by a nest of the termite Macrotermes michaelseni in Kajiado, Kenya. Journal of Zoology. 1982, 198 (2): 237–247. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1982.tb02073.x.

- ^ Cornelius, M.L.; Osbrink, W.L. Effect of soil type and moisture availability on the foraging behavior of the Formosan subterranean termite (Isoptera: Rhinotermitidae).. Journal of Economic Entomology. 2010, 103 (3): 799–807. PMID 20568626. doi:10.1603/EC09250.

- ^ Toledo Lima, J.; Costa-Leonardo, A.M. Subterranean termites (Isoptera: Rhinotermitidae): Exploitation of equivalent food resources with different forms of placement. Insect Science. 2012, 19 (3): 412–418. doi:10.1111/j.1744-7917.2011.01453.x.

- ^ Jmhasly, P.; Leuthold, R.H. Intraspecific colony recognition in the termites Macrotermes subhyalinus and Macrotermes bellicosus (Isoptera, Termitidae). Insectes Sociaux. 1999, 46 (2): 164–170. doi:10.1007/s000400050128.

- ^ Messenger, M.T.; Su, N.Y. Agonistic behavior between colonies of the Formosan subterranean termite (Isoptera: Rhinotermitidae) from Louis Armstrong Park, New Orleans, Louisiana. Sociobiology. 2005, 45 (2): 331–345.

- ^ Korb, J.; Weil, T.; Hoffmann, K.; Foster, K.R.; Rehli, M. A gene necessary for reproductive suppression in termites. Science. 2009, 324 (5928): 758. Bibcode:2009Sci...324..758K. PMID 19423819. doi:10.1126/science.1170660.

- ^ 155.0 155.1 155.2 Mathew, T.T.G.; Reis, R.; DeSouza, O.; Ribeiro, S.P. Predation and interference competition between ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) and arboreal termites (Isoptera: Termitidae) (PDF). Sociobiology. 2005, 46 (2): 409–419 [2020-07-04]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2021-04-11).

- ^ 156.0 156.1 Costa-Leonardo, A.M.; Haifig, I. Pheromones and exocrine glands in Isoptera. Vitamins and Hormones. 2010, 83: 521–549. ISBN 9780123815163. PMID 20831960. doi:10.1016/S0083-6729(10)83021-3.

- ^ 157.0 157.1 157.2 157.3 157.4 157.5 157.6 Krishna, K. Termite. Encyclopædia Britannica. [11 September 2015]. (原始内容存档于2021-04-21).

- ^ Costa-Leonardo, A.M.; Casarin, F.E.; Lima, J.T. Chemical communication in isoptera. Neotropical Entomology. 2009, 38 (1): 747–52. PMID 19347093. doi:10.1590/S1519-566X2009000100001.

- ^ Richard, F.-J.; Hunt, J.H. Intracolony chemical communication in social insects (PDF). Insectes Sociaux. 2013, 60 (3): 275–291 [2020-07-04]. doi:10.1007/s00040-013-0306-6. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2016-03-04).

- ^ Dronnet, S.; Lohou, C.; Christides, J.P.; Bagnères, A.G. Cuticular hydrocarbon composition reflects genetic relationship among colonies of the introduced termite Reticulitermes santonensis Feytaud. Journal of Chemical Ecology. 2006, 32 (5): 1027–1042. PMID 16739021. doi:10.1007/s10886-006-9043-x.

- ^ Wilson, D.S. Above ground predator defense in the harvester termite, Hodotermes mossambicus (Hagen). Journal of the Entomological Society of Southern Africa. 1977, 40: 271–282.

- ^ Rosengaus, R.B.; Traniello, J.F.A.; Chen, T.; Brown, J.J.; Karp, R.D. Immunity in a social insect. Naturwissenschaften. 1999, 86 (12): 588–591. Bibcode:1999NW.....86..588R. doi:10.1007/s001140050679.

- ^ 163.0 163.1 Wilson, E.O. A window on eternity: a biologist's walk through Gorongosa National Park First. Simon & Schuster. 2014: 85, 90. ISBN 978-1-4767-4741-5.

- ^ Belbin, R.M. The Coming Shape of Organization. New York: Routledge. 2013: 27. ISBN 978-1-136-01553-3.

- ^ 165.0 165.1 Prestwich, G.D.; Chen, D. Soldier defense secretions of Trinervitermes bettonianus (Isoptera, Nasutitermitinae): Chemical variation in allopatric populations. Journal of Chemical Ecology. 1981, 7 (1): 147–157. PMID 24420434. doi:10.1007/BF00988642.

- ^ Prestwich, G.D. From tetracycles to macrocycles. Tetrahedron. 1982, 38 (13): 1911–1919. doi:10.1016/0040-4020(82)80040-9.

- ^ Chen, J.; Henderson, G.; Grimm, C. C.; Lloyd, S. W.; Laine, R. A. Termites fumigate their nests with naphthalene. Nature. 1998-04-09, 392 (6676): 558–559. Bibcode:1998Natur.392..558C. doi:10.1038/33305.

- ^ Piper, Ross, Extraordinary Animals: An Encyclopedia of Curious and Unusual Animals, Greenwood Press: 26, 2007 [2020-07-04], ISBN 978-0-313-33922-6, (原始内容存档于2021-04-11)

- ^ Bordereau, C.; Robert, A.; Van Tuyen, V.; Peppuy, A. Suicidal defensive behaviour by frontal gland dehiscence in Globitermes sulphureus Haviland soldiers (Isoptera). Insectes Sociaux. 1997, 44 (3): 289–297. doi:10.1007/s000400050049.

- ^ Sobotnik, J.; Bourguignon, T.; Hanus, R.; Demianova, Z.; Pytelkova, J.; Mares, M.; Foltynova, P.; Preisler, J.; Cvacka, J.; Krasulova, J.; Roisin, Y. Explosive backpacks in old termite workers. Science. 2012, 337 (6093): 436. Bibcode:2012Sci...337..436S. PMID 22837520. doi:10.1126/science.1219129.

- ^ ŠobotnÍk, J.; Bourguignon, T.; Hanus, R.; Weyda, F.; Roisin, Y. Structure and function of defensive glands in soldiers of Glossotermes oculatus (Isoptera: Serritermitidae). Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 2010, 99 (4): 839–848. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.2010.01392.x.

- ^ Ulyshen, M.D.; Shelton, T.G. Evidence of cue synergism in termite corpse response behavior. Naturwissenschaften. 2011, 99 (2): 89–93. Bibcode:2012NW.....99...89U. PMID 22167071. doi:10.1007/s00114-011-0871-3.

- ^ Su, N.Y. Response of the Formosan subterranean termites (Isoptera: Rhinotermitidae) to baits or nonrepellent termiticides in extended foraging arenas.. Journal of Economic Entomology. 2005, 98 (6): 2143–2152. PMID 16539144. doi:10.1603/0022-0493-98.6.2143.

- ^ Sun, Q.; Haynes, K.F.; Zhou, X. Differential undertaking response of a lower termite to congeneric and conspecific corpses. Scientific Reports. 2013, 3: 1650. Bibcode:2013NatSR...3E1650S. PMC 3629736

. PMID 23598990. doi:10.1038/srep01650.

. PMID 23598990. doi:10.1038/srep01650.

- ^ 175.0 175.1 Neoh, K.-B.; Yeap, B.-K.; Tsunoda, K.; Yoshimura, T.; Lee, C.Y.; Korb, J. Do termites avoid carcasses? behavioral responses depend on the nature of the carcasses. PLoS ONE. 2012, 7 (4): e36375. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...736375N. PMC 3338677

. PMID 22558452. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0036375.

. PMID 22558452. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0036375.

- ^ Matsuura, K. Termite-egg mimicry by a sclerotium-forming fungus. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2006, 273 (1591): 1203–1209. PMC 1560272

. PMID 16720392. doi:10.1098/rspb.2005.3434.

. PMID 16720392. doi:10.1098/rspb.2005.3434.

- ^ Matsuura, K.; Yashiro, T.; Shimizu, K.; Tatsumi, S.; Tamura, T. Cuckoo fungus mimics termite eggs by producing the cellulose-digesting enzyme β-glucosidase. Current Biology. 2009, 19 (1): 30–36. PMID 19110429. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2008.11.030.

- ^ Howard, R.W.; McDaniel, C.A.; Blomquist, G.J. Chemical mimicry as an integrating mechanism: cuticular hydrocarbons of a termitophile and its host. Science. 1980, 210 (4468): 431–433. Bibcode:1980Sci...210..431H. PMID 17837424. doi:10.1126/science.210.4468.431.

- ^ Watson, J.A.L. Austrospirachtha mimetes a new termitophilous corotocine from Northern Australia (Coleoptera: Staphylinidae). Australian Journal of Entomology. 1973, 12 (4): 307–310. doi:10.1111/j.1440-6055.1973.tb01678.x.

- ^ Forbes, H.O. Termites Kept in Captivity by Ants. Nature. 1878, 19 (471): 4–5. Bibcode:1878Natur..19....4F. doi:10.1038/019004b0.

- ^ Darlington, J. Attacks by doryline ants and termite nest defences (Hymenoptera; Formicidae; Isoptera; Termitidae). Sociobiology. 1985, 11: 189–200.

- ^ Quinet Y, Tekule N & de Biseau JC. Behavioural Interactions Between Crematogaster brevispinosa rochai Forel (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) and Two Nasutitermes Species (Isoptera: Termitidae). Journal of Insect Behavior. 2005, 18 (1): 1–17. doi:10.1007/s10905-005-9343-y.

- ^ Coty, D.; Aria, C.; Garrouste, R.; Wils, P.; Legendre, F.; Nel, A.; Korb, J. The First Ant-Termite Syninclusion in Amber with CT-Scan Analysis of Taphonomy. PLoS ONE. 2014, 9 (8): e104410. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9j4410C. PMC 4139309

. PMID 25140873. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0104410.

. PMID 25140873. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0104410.

- ^ 184.0 184.1 Santos, P.P.; Vasconcellos, A.; Jahyny, B.; Delabie, J.H.C. Ant fauna (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) associated to arboreal nests of Nasutitermes spp: (Isoptera, Termitidae) in a cacao plantation in southeastern Bahia, Brazil. Revista Brasileira de Entomologia. 2010, 54 (3): 450–454. doi:10.1590/S0085-56262010000300016.

- ^ Jaffe, K.; Ramos, C.; Issa, S. Trophic Interactions Between Ants and Termites that Share Common Nests. Annals of the Entomological Society of America. 1995, 88 (3): 328–333. doi:10.1093/aesa/88.3.328.

- ^ Trager, J.C. A Revision of the fire ants, Solenopsis geminata group (Hymenoptera: Formicidae: Myrmicinae). Journal of the New York Entomological Society. 1991, 99 (2): 141–198. JSTOR 25009890. doi:10.5281/zenodo.24912.

- ^ 187.0 187.1 Cingel, N.A. van der. An atlas of orchid pollination: America, Africa, Asia and Australia. Rotterdam: Balkema. 2001: 224. ISBN 978-90-5410-486-5.

- ^ McHatton, R. Orchid Pollination: exploring a fascinating world (PDF). The American Orchid Society: 344. 2011 [5 September 2015]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2021-04-11).

- ^ Cowie, R. Journey to a Waterfall a biologist in Africa. Raleigh, North Carolina: Lulu Press. 2014: 169. ISBN 978-1-304-66939-1.

- ^ 190.0 190.1 Tan, K.H. Environmental Soil Science 3rd. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press. 2009: 105–106. ISBN 978-1-4398-9501-6.

- ^ 191.0 191.1 Clark, Sarah. Plant extract stops termites dead. ABC. 15 November 2005 [8 February 2014]. (原始内容存档于15 June 2009).

- ^ Vasconcellos, Alexandre; Bandeira, Adelmar G.; Moura, Flávia Maria S.; Araújo, Virgínia Farias P.; Gusmão, Maria Avany B.; Reginaldo, Constantino. Termite assemblages in three habitats under different disturbance regimes in the semi-arid Caatinga of NE Brazil. Journal of Arid Environments (Elsevier). February 2010, 74 (2): 298–302. Bibcode:2010JArEn..74..298V. ISSN 0140-1963. doi:10.1016/j.jaridenv.2009.07.007.

- ^ 193.0 193.1 Noirot, C.; Darlington, J.P.E.C. Termite Nests: Architecture, Regulation and Defence in Termites: Evolution, Sociality, Symbioses, Ecology. Springer. 2000: 121–139. ISBN 978-94-017-3223-9. doi:10.1007/978-94-017-3223-9_6.

- ^ Bignell, Roisin & Lo 2010,第20页.

- ^ 195.0 195.1 Eggleton, P.; Bignell, D.E.; Sands, W.A.; Mawdsley, N. A.; Lawton, J. H.; Wood, T.G.; Bignell, N.C. The Diversity, Abundance and Biomass of Termites under Differing Levels of Disturbance in the Mbalmayo Forest Reserve, Southern Cameroon. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 1996, 351 (1335): 51–68. Bibcode:1996RSPTB.351...51E. doi:10.1098/rstb.1996.0004.

- ^ 196.0 196.1 196.2 196.3 196.4 Bignell, Roisin & Lo 2010,第21页.

- ^ De Visse, S.N.; Freymann, B.P.; Schnyder, H. Trophic interactions among invertebrates in termitaria in the African savanna: a stable isotope approach. Ecological Entomology. 2008, 33 (6): 758–764 [2020-07-04]. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2311.2008.01029.x. (原始内容存档于2021-04-11).

- ^ 198.0 198.1 198.2 Bignell, Roisin & Lo 2010,第22页.

- ^ Vane, C.H.; Kim, A.W.; Moss-Hayes, V.; Snape, C.E.; Diaz, M.C.; Khan, N.S.; Engelhart, S.E.; Horton, B.P. Degradation of mangrove tissues by arboreal termites (Nasutitermes acajutlae) and their role in the mangrove C cycle (Puerto Rico): Chemical characterization and organic matter provenance using bulk δ13C, C/N, alkaline CuO oxidation-GC/MS, and solid-state (PDF). Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems. 2013, 14 (8): 3176–3191 [2020-07-04]. Bibcode:2013GGG....14.3176V. doi:10.1002/ggge.20194. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2016-10-07).

- ^ 200.0 200.1 Roisin, Y.; Pasteels, J. M. Reproductive mechanisms in termites: Polycalism and polygyny in Nasutitermes polygynus and N. costalis. Insectes Sociaux. 1986, 33 (2): 149–167. doi:10.1007/BF02224595.

- ^ Perna, A.; Jost, C.; Couturier, E.; Valverde, S.; Douady, S.; Theraulaz, G. The structure of gallery networks in the nests of termite Cubitermes spp. revealed by X-ray tomography.. Die Naturwissenschaften. 2008, 95 (9): 877–884. Bibcode:2008NW.....95..877P. PMID 18493731. doi:10.1007/s00114-008-0388-6.

- ^ Glenday, Craig. Guinness World Records 2014. 2014: 33. ISBN 978-1-908843-15-9.

- ^ Jacklyn, P. Evidence for Adaptive Variation in the Orientation of Amitermes (Isoptera, Termitinae) Mounds From Northern Australia. Australian Journal of Zoology. 1991, 39 (5): 569. doi:10.1071/ZO9910569.

- ^ Jacklyn, P.M.; Munro, U. Evidence for the use of magnetic cues in mound construction by the termite Amitermes meridionalis (Isoptera : Termitinae). Australian Journal of Zoology. 2002, 50 (4): 357. doi:10.1071/ZO01061.

- ^ Grigg, G.C. Some Consequences of the Shape and Orientation of 'magnetic' Termite Mounds (PDF). Australian Journal of Zoology. 1973, 21 (2): 231–237. doi:10.1071/ZO9730231.

- ^ 206.0 206.1 Hadlington, P. Australian Termites and Other Common Timber Pests 2nd. Kensington, NSW, Australia: New South Wales University Press. 1996: 28–30. ISBN 978-0-86840-399-1.

- ^ 207.0 207.1 Kahn, L.; Easton, B. Shelter II. Bolinas, California: Shelter Publications. 2010: 198. ISBN 978-0-936070-49-0.

- ^ 208.0 208.1 208.2 208.3 208.4 208.5 208.6 208.7 Su, N.Y.; Scheffrahn, R.H. Termites as Pests of Buildings in Termites: Evolution, Sociality, Symbioses, Ecology. Springer Netherlands. 2000: 437–453. ISBN 978-94-017-3223-9. doi:10.1007/978-94-017-3223-9_20.

- ^ Thorne, Ph.D, Barbara L. NPMA Research Report On Subterranean Termites. Dunn Loring, VA: NPMA. 1999: 22 [2020-07-04]. (原始内容存档于2021-04-11).

- ^ Termites. Victorian Building Authority. Government of Victoria. 2014 [20 September 2015]. (原始内容存档于2018-02-03).

- ^ Thorne, Ph.D, Barbara L. NPMA Research Report On Subterranean Termites. Dunn Loring, VA: NPMA. 1999: 2 [2020-07-04]. (原始内容存档于2021-04-11).

- ^ Grace, J.K.; Cutten, G.M.; Scheffrahn, R.H.; McEkevan, D.K. First infestation by Incisitermes minor of a Canadian building (Isoptera: Kalotermitidae). Sociobiology. 1991, 18: 299–304.

- ^ Heather, N.W. The exotic drywood termite Cryptotermes brevis (Walker) (Isoptera : Kalotermitidae) and endemic Australian drywood termites in Queensland. Australian Journal of Entomology. 1971, 10 (2): 134–141. doi:10.1111/j.1440-6055.1971.tb00022.x.

- ^ 214.0 214.1 Sands, W.A. Termites as Pests of Tropical Food Crops. Tropical Pest Management. 1973, 19 (2): 167–177. doi:10.1080/09670877309412751.

- ^ 215.0 215.1 215.2 215.3 Flores, A. New Assay Helps Track Termites, Other Insects. Agricultural Research Service (United States Department of Agriculture). 17 February 2010 [15 January 2015]. (原始内容存档于2016-03-03).

- ^ Su, N.Y.; Scheffrahn, R.H. Economically important termites in the United States and their control (PDF). Sociobiology. 1990, 17: 77–94. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2011-08-12).

- ^ Thorne, Ph.D, Barbara L. NPMA Research Report On Subterranean Termites. Dunn Loring, VA: NPMA. 1999: 40 [2020-07-04]. (原始内容存档于2021-04-11).

- ^ Elliott, Sara. How can copper keep termites at bay?. HowStuffWorks. 26 May 2009 [2020-07-04]. (原始内容存档于2020-07-24).

- ^ 219.0 219.1 219.2 Figueirêdo, R.E.C.R.; Vasconcellos, A.; Policarpo, I.S.; Alves, R.R.N. Edible and medicinal termites: a global overview. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine. 2015, 11 (1): 29. PMC 4427943

. PMID 25925503. doi:10.1186/s13002-015-0016-4.

. PMID 25925503. doi:10.1186/s13002-015-0016-4.

- ^ 220.0 220.1 220.2 220.3 Nyakupfuka, A. Global Delicacies: Discover Missing Links from Ancient Hawaiian Teachings to Clean the Plaque of your Soul and Reach Your Higher Self.. Bloomington, Indiana: BalboaPress. 2013: 40–41. ISBN 978-1-4525-6791-4.

- ^ 221.0 221.1 Bodenheimer, F.S. Insects as Human Food: A Chapter of the Ecology of Man. Netherlands: Springer. 1951: 331–350. ISBN 978-94-017-6159-8.

- ^ Geissler, P.W. The significance of earth-eating: social and cultural aspects of geophagy among Luo children. Africa. 2011, 70 (4): 653–682. doi:10.3366/afr.2000.70.4.653.

- ^ Knudsen, J.W. Akula udongo (earth eating habit): a social and cultural practice among Chagga women on the slopes of Mount Kilimanjaro. African Journal of Indigenous Knowledge Systems. 2002, 1 (1): 19–26. ISSN 1683-0296. OCLC 145403765. doi:10.4314/indilinga.v1i1.26322.

- ^ Nchito, M.; Wenzel Geissler, P.; Mubila, L.; Friis, H.; Olsen, A. Effects of iron and multimicronutrient supplementation on geophagy: a two-by-two factorial study among Zambian schoolchildren in Lusaka. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2004, 98 (4): 218–227. PMID 15049460. doi:10.1016/S0035-9203(03)00045-2.

- ^ Saathoff, E.; Olsen, A.; Kvalsvig, J.D.; Geissler, P.W. Geophagy and its association with geohelminth infection in rural schoolchildren from northern KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2002, 96 (5): 485–490. PMID 12474473. doi:10.1016/S0035-9203(02)90413-X.

- ^ Katayama, N.; Ishikawa, Y.; Takaoki, M.; Yamashita, M.; Nakayama, S.; Kiguchi, K.; Kok, R.; Wada, H.; Mitsuhashi, J. Entomophagy: A key to space agriculture (PDF). Advances in Space Research. 2008, 41 (5): 701–705 [2020-07-04]. Bibcode:2008AdSpR..41..701S. doi:10.1016/j.asr.2007.01.027. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2018-09-27).

- ^ Mitchell, J.D. Termites as pests of crops, forestry, rangeland and structures in Southern Africa and their control. Sociobiology. 2002, 40 (1): 47–69 [2020-07-04]. ISSN 0361-6525. (原始内容存档于2015-09-25).

- ^ Löffler, E.; Kubiniok, J. Landform development and bioturbation on the Khorat plateau, Northeast Thailand (PDF). Natural History Bulletin of the Siam Society. 1996, 44: 199–216 [2020-07-04]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2021-04-11).

- ^ 229.0 229.1 Capinera, J.L. Encyclopedia of Entomology 2nd. Dordrecht: Springer. 2008: 3033–3037, 3754. ISBN 978-1-4020-6242-1.

- ^ Evans, T.A.; Dawes, T.Z.; Ward, P.R.; Lo, N. Ants and termites increase crop yield in a dry climate. Nature Communications. 2011, 2: 262. Bibcode:2011NatCo...2..262E. PMC 3072065

. PMID 21448161. doi:10.1038/ncomms1257.

. PMID 21448161. doi:10.1038/ncomms1257.

- ^ 231.0 231.1 231.2 231.3 Termite Power. DOE Joint Genome Institute. United States Department of Energy. 14 August 2006 [11 September 2015]. 原始内容存档于22 September 2006.

- ^ Hirschler, B. Termites' gut reaction set for biofuels. ABC News. 22 November 2007 [8 January 2015]. (原始内容存档于2021-04-11).

- ^ Roach, J. Termite Power: Can Pests' Guts Create New Fuel?. National Geographic News. 14 March 2006 [11 September 2015]. (原始内容存档于2017-03-18).

- ^ Werfel, J.; Petersen, K.; Nagpal, R. Designing Collective Behavior in a Termite-Inspired Robot Construction Team. Science. 2014, 343 (6172): 754–758. Bibcode:2014Sci...343..754W. PMID 24531967. doi:10.1126/science.1245842.

- ^ Gibney, E. Termite-inspired robots build castles. Nature. 2014 [2020-07-04]. doi:10.1038/nature.2014.14713. (原始内容存档于2021-04-11).

- ^ 236.0 236.1 236.2 Termites Green Architecture in the Tropics. The Architect. Architectural Association of Kenya. [17 October 2015]. (原始内容存档于2016-03-22).

- ^ Tan, A.; Wong, N. Parameterization Studies of Solar Chimneys in the Tropics. Energies. 2013, 6 (1): 145–163. doi:10.3390/en6010145.

- ^ Tsoroti, S. What's that building? Eastgate Mall. Harare News. 15 May 2014 [8 January 2015]. (原始内容存档于2021-04-11).

- ^ Im Zoo Basel fliegen die Termiten aus. Neue Zürcher Zeitung. 8 February 2014 [21 May 2011]. (原始内容存档于2012-03-14) (德语).

- ^ Van-Huis, H. Insects as food in Sub-Saharan Africa (PDF). Insect Science and Its Application. 2003, 23 (3): 163–185 [2020-07-04]. doi:10.1017/s1742758400023572. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2017-07-13).

- ^ 241.0 241.1 Neoh, K.B. Termites and human society in Southeast Asia (PDF). The Newsletter. 2013, 30 (66): 1–2 [2020-07-04]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2014-04-02).

外部链接

[编辑]- Termites. University of Nebraska. [2008-04-29]. (原始内容存档于2006-01-16) (英语).

- A summary of termite control methods

- University of California advice on Drywood Termites (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- Termite Pest Control Information - USA National Pesticide Information Center (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- Catalogue of the termites of the World

- Pictures of termites (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- Transitional Species in Insect Evolution (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- Did the Termites Cause Laterites? (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- Cretaceous Termites and Soil Phosphorus (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- Beneficial Uses of Termites

- Texas A&M University Department of Entomology - Center for Urban & Structural Entomology

- The Soul of the White Ant - Eugène N. Marais (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- Urban Entomology Program University of Toronto

- Harvard University fact sheet on Eastern Subterranean Termites

- Isoptera: termites (CSIRO Australia Entomology)。

- 'Termite guts can save the planet', says Nobel laureate (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- USA Pest Management Association's fact sheet on termites

- Termite Control Information from a US chemical supply company (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- VLC Pest Control Service Tw (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- Bugsdied Pest Control HK (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)