使用者:PhiLiP/文藝復興

文藝復興(義大利語:Rinascimento,由ri-「重新」和nascere「出生」構成)[1]是一場發生在14世紀至17世紀的文化運動,在中世紀晚期發源於佛羅倫斯,後擴展至歐洲各國。「文藝復興」一詞亦可粗略地指代這一歷史時期,但由於歐洲各地因其引發的變化並非完全一致,故「文藝復興」只是對這一時期的通稱。這場文化運動囊括了對古典文獻的重新學習,在繪畫方面直線透視法的發展,以及逐步而廣泛開展的教育變革。傳統觀點認為,這種知識上的轉變讓文藝復興發揮了銜接中世紀和現代的作用。儘管文藝復興在知識、社會和政治各個方面都引發了革命,但令其聞名於世的或許還在於這一時期的藝術成就,以及李奧納多·達文西、米開朗琪羅等博學家做出的貢獻。[2][3]

一般認為,文藝復興始於14世紀托斯卡納的佛羅倫斯,但對此尚有質疑之聲。[4]就這場運動的起源和特點而言,多種理論已經提出了各自的見解,但其關注的焦點不盡相同:其中包括有當時佛羅倫斯的社會和公民的特點;當地的政治結構;當地統治階級美第奇家族的贊助[5];以及鄂圖曼土耳其人攻陷君士坦丁堡後,大批流入義大利的希臘語學者及書籍。[6][7][8]

史學上關於文藝復興的內容很多且頗為複雜,而「文藝復興」作為詞彙的作用,及其作為歷史過渡期的意義,都引發了史學家的諸多爭論。[9]文藝復興能否被稱作是中世紀後的文化「進步」,一些史學家對此是持懷疑態度的:他們認為,這個階段只是對古典時代抱持悲觀與緬懷的時期。[10]而另一些人則關注兩個時代之間的連續性。[11]實際上,現在已有人提出不應繼續使用這個詞彙,因為他們認為「文藝復興」一詞只是現代主義的產物,是使用歷史來驗證和發揚當代理想的工具。[12]「文藝復興」一詞也被用於其他歷史或文化運動,卡洛林文藝復興和12世紀的文藝復興就是這樣的例子。

概述[編輯]

| 文藝復興 |

|---|

|

| 主題 |

| 區域 |

|

文藝復興這場文化運動對近代歐洲的學術生活造成了深刻的影響。它從義大利興起,在16世紀時已擴大至歐洲各國,其影響遍及文學、哲學、藝術、政治、科學、宗教等知識探索的各個方面。文藝復興時期的學者在學術研究中使用人文主義的方法,並在藝術創作中追尋現實主義和人類的情感。[13]

在歐洲的修道院圖書館中和沒落的拜占庭帝國里,文藝復興時期的思想家們搜集到了古典時代的文學、歷史和演說文獻。這些文獻大多使用拉丁語或古希臘語寫成,多數內容晦澀難懂。文藝復興時期的學者同12世紀文藝復興時期的中世紀學者最顯著的差別在於,前者將文學和歷史等文化方面的文獻作為新的研究重點,而後者只專注於自然科學、物理學和數學的希臘語和阿拉伯語典籍。文藝復興時期的人文學者並不反對基督教;恰恰相反,這一時期眾多的偉大作品都是為宗教而作,而且許多藝術作品得到了教會的贊助。然而,從文化生活的其他領域可以看出,學者們對待宗教的方式還是發生了微妙的轉變。[14]此外,包括希臘語《新約》在內的大量希臘語基督教著作從拜占庭流入了西歐,這是自古典時代末期後,西方學者首次接觸到如此具有吸引力的內容。這些希臘語的基督教作品,特別是由洛倫佐·瓦拉和伊拉斯謨整理完善的希臘語原文《新約》,為後來的宗教改革創造了條件。

馬薩喬等藝術家們為了更自然地表現透視和明暗關係,都在改善自己的技法,努力做到能真實地描摹人體形態。以尼可羅·馬基亞維利為首的政治哲學家們理性地分析政治生活,設法讓敘述符合事實。米蘭多拉的著名作品《論人的尊嚴》(De hominis dignitate,1486年)為義大利文藝復興的人文主義作出了巨大貢獻;文中論述了哲學、自然思想、宗教信仰和巫術這一系列的話題,並以理性為依據,有力地回擊了反對者。為了更好地學習古拉丁語和希臘語,文藝復興時期的作家們開始更多地使用這些地方語言寫作;而印刷術的推廣亦使得更多的人能夠接觸到各種書籍,特別是聖經。[15]

總而言之,文藝復興可被視為學者們研究和改善俗世的一次嘗試,他們通過復興古典時代思想和創新思考方式來推動變革。羅德尼·斯塔克(Rodney Stark)等學者[16]認為中世紀盛期發生在義大利城邦的改革的意義並不亞於文藝復興運動,前者產生了回應型政府、基督教和資本主義萌芽的結合體。這種分析認為,鑑於歐洲大國(法國和西班牙)受君主專制統治,而其他國家則受教會的直接控制;因而只有義大利的獨立城市共和國才能從僧院等級承襲資本主義的原則,進而引發了一場規模空前的商業革命,並為隨後發生的文藝復興運動打下了經濟基礎。

起源[編輯]

絕大部分歷史學家相信,對文藝復興這一概念的闡述源於13世紀晚期的佛羅倫斯,特別是在但丁(1265年-1321年)、彼特拉克(1304年-1374年)的著作以及喬托(1267年-1337年)的繪作誕生的時代。有的學者非常明確地給出了文藝復興開始的時間,其中一位提出,應以1401年洛倫佐·吉貝爾蒂和菲利波·布魯內萊斯基這兩位天才雕塑家競爭佛羅倫斯聖母百花大教堂洗禮堂銅門的合約為標誌。[17]而其他學者則認為,是藝術家和博學家(包括布魯內萊斯基、吉貝爾蒂、多那太羅和馬薩喬等人)為獲得藝術品創作委託的普遍競爭,激發了文藝復興時期的創造力。但是,對於文藝復興興起於義大利、發生於當時的原因,學界至今仍有著諸多爭議;相應地,也有多種理論用於解釋文藝復興的起源問題。

文藝復興人文主義的拉丁語和希臘語時期[編輯]

中世紀盛期的拉丁語學者全身心地研究自然科學、哲學、數學的希臘語和阿拉伯文著作,[18]與之形成鮮明對比的是文藝復興時期的學者,他們對重尋和研究拉丁語及希臘語的文學、歷史與演講資料更感興趣。概括而言,這一時期開始於14世紀,與拉丁語時期同步。彼特拉克、薩盧塔蒂(1331年-1406年)、尼科利(1364年-1437年)及波焦·布拉喬利尼(1380年-1459年)等文藝復興學者,為了搜尋諸如西塞羅、李維和塞內卡等希臘語作家的著作而找遍了歐洲的各大圖書館。[19]截至15世紀早期,已有大部分這樣的拉丁語文學作品被找到;而當西歐學者開始尋找古希臘的文學、歷史、演講及神學資料時,文藝復興人文主義的希臘語時期也隨之開始。[20]

在西歐,從古典時代後期就有對拉丁語文獻的保存和研究,但對古希臘語文獻的研究卻在整個中世紀都極為有限。西歐和伊斯蘭世界分別從其中世紀盛期和中世紀開始,都對古希臘語的科學、數學和哲學著作有所研究;但無論是在拉丁語地區還是伊斯蘭世界,對希臘語文學、演講及歷史作品(如荷馬、修昔底德以及其他古希臘的劇作家、雄辯家等)的研究都未曾有過:在中世紀,只有拜占庭的學者才研究過這些著作。文藝復興時期學者的一大成就,就是自古典時代後期以來,第一次將希臘語文化作品從整體上引入了西歐。該運動讓希臘語的文學、歷史、演講和神學資料重新進入了西歐學校的課程中:這通常會以薩盧塔蒂邀請拜占庭外交官和學者赫里索洛拉斯(約1355年-1415年)到佛羅倫斯講授希臘語為標誌,[23]後者的希臘語造詣對此發揮了關鍵的作用。另一位重要的希臘語拜占庭學者是德美特里·卡爾孔狄利斯(1421年-1511年),他在義大利的帕多瓦[24]、佩魯賈[25]、米蘭和佛羅倫斯[26]講授了四十餘年的希臘語和柏拉圖哲學。他的學生有:約翰·羅伊希林、亞努斯·拉斯卡里斯、波利齊亞諾、利奧十世、巴爾達薩雷·卡斯蒂廖內[27]、吉利奧·格雷戈里奧·吉拉爾迪、斯特凡諾·內格里(Stefano Negri)及喬瓦尼·馬里亞·卡塔內奧(Giovanni Maria Cattaneo)。[28][29]

1453年,隨著拜占庭帝國的徹底瓦解,鄂圖曼土耳其關閉了它的高等學府。大批希臘語學者因而被迫流亡義大利乃至更遠之處,同時也將他們的希臘語手稿和古希臘語文學造詣帶到了西歐:其中的一部分已在西方佚失了數百年之久。[30]

義大利的社會與政治結構[編輯]

基於中世紀後期義大利的獨特政治結構,部分學者推理說:當地與眾不同的社會氛圍為義大利出現罕見的文化繁榮提供了必要條件。在近代,義大利並非一個統一的政治實體,而是由一些城邦和領地組成:控制著南部的拿波里王國,位於中部的佛羅倫斯共和國和教皇國,分別位於北部和西部的熱那亞與米蘭,以及位於東部的威尼斯。15世紀的義大利是歐洲城市化水平最高的地區。[31]許多義大利城市就建立在古羅馬建築的廢墟之上;從表面上看,這就將文藝復興的古典性及其發祥於羅馬帝國心臟地帶的事實聯繫在了一起。[32]

歷史學與政治哲學家昆廷·斯金納指出,弗賴辛主教奧托(1114年-1158年)在12世紀來到義大利時,曾注意到這裡出現了一種新的政治和社會組織形態,並觀察到義大利似乎已開始脫離封建制度,將商人和商業作為其社會基礎。與此相關的,是壁畫《好政府與壞政府的諷喻》(Allegory of Good and Bad Government)所表達出的反君主制思想;這幅著名的早期文藝復興壁畫位於錫耶納,由安布羅焦·洛倫采蒂繪於1338年至1340年;他通過這幅畫傳達出了對公平、公正、共和與善治的強烈渴盼。儘管受到教廷與神聖羅馬帝國的牽制,但這些城市共和國依舊不懈地追求著自由的理念。斯金納指出當地有很多人都在極力維護自由,例如馬泰奧·帕爾米耶里(1406年-1475年)不僅歌頌了佛羅倫斯藝術、雕塑及建築方面的天才藝術家,還對「同時在佛羅倫斯出現的道德、社會及政治哲學的繁榮」[33]發出了讚美之辭。[34]

即使是義大利中心以外的城市與城邦,亦因其商人共和國的政體而備受關注,譬如當時的佛羅倫斯共和國;而其中最為出色的當屬威尼斯共和國。儘管這些政體在實際上仍是寡頭政治,與現代的民主也鮮有類似之處;但他們確實具備了民主的特徵,其響應型政府亦已具備了參與治理的形式及對自由的信念。[35][36][37]這些城邦提供的相對政治自由,有利於學術和藝術的進步。[38]同樣的,威尼斯等位於重要貿易中心的義大利城市,也成為了智慧交匯的樞紐。世界各地的——尤其是累范特地區的——商人帶著各自的觀點來到這裡。出產優質玻璃的威尼斯,在這時成為了歐洲與東方的貿易門戶;而佛羅倫斯則成為了紡織業的中心。商業活動為義大利帶來的巨大財富,讓藝術家得以創作大型的公共及私人藝術作品,同時也讓個人擁有了更多的閒暇時間用來學習。[38]

黑死病[編輯]

有種理論提出,1348至1350年間的黑死病給歐洲帶來了沉重的打擊,其中以義大利、特別是佛羅倫斯的疫情尤其具有毀滅性,這導致14世紀義大利人的世界觀發生了變化。這種理論推測,直面死亡的體驗,讓義大利的思想家們開始將其關注的對象從靈性和來世轉向現世。[39]同時,這種理論還指出,黑死病引發了對宗教的新一輪虔誠,使人們開始大量地資助宗教題材作品的創作。[40]然而,該理論並不能充分地解釋文藝復興發生在14世紀義大利的原因,因為黑死病的大流行也對整個歐洲造成了同樣的影響。因此,文藝復興首先出現在義大利,極有可能是上述多種因素共同作用的結果。[9]

黑死病帶來的劫難令人口銳減,進而導致勞動力嚴重缺乏。在歐洲,這種趨勢讓工人特別是熟練工人掌握了更多的話語權。與此同時,工人和商人們從統治者手裡接掌了權力,這在一些較小的國家中尤為明顯(譬如當時分裂中的義大利)。因此,撇開黑死病所帶來的精神和心理影響不談,這場瘟疫的經濟影響乃至隨後的政治影響,可能為文藝復興的出現做了鋪墊。

佛羅倫斯的文化環境[編輯]

It has long been a matter of debate why the Renaissance began in Florence, and not elsewhere in Italy. Scholars have noted several features unique to Florentine cultural life which may have caused such a cultural movement. Many have emphasized the role played by the Medici, a banking family and later ducal housefamily, in patronizing and stimulating the arts. Lorenzo de' Medici (1449 – 1492) was the catalyst for an enormous amount of arts patronage, encouraging his countryman to commission works from Florence's leading artists, including Leonardo da Vinci, Sandro Botticelli, and Michelangelo Buonarroti.[5]

文藝復興為什麼發端於佛羅倫斯而不是義大利的其他地方,這是一個長期以來爭論頗多的問題。一些學者注意到佛羅倫斯的文化生活具備一些獨有的特點,也許這些就是引發這場文化運動的原因。佛羅倫斯的梅第奇家族起初從事銀行業,後來得到了公爵頭銜。這一家族曾長期贊助並激勵藝術事業,在這場文化運動中扮演了舉足輕重的角色。洛倫佐·德·梅第奇(1449-1492)推動了大量對藝術的贊助,並鼓勵國民向佛羅倫斯的頂尖藝術家訂購作品,這其中就包括達文西、波提切利和米開朗基羅。【5】

The Renaissance was certainly underway before Lorenzo came to power; indeed, before the Medici family itself achieved hegemony in Florentine society. Some historians have postulated that Florence was the birthplace of the Renaissance as a result of luck, i.e. because "Great Men" were born there by chance.[41] Da Vinci, Botticelli and Michelangelo were all born in Tuscany. Arguing that such chance seems improbable, other historians have contended that these "Great Men" were only able to rise to prominence because of the prevailing cultural conditions at the time.[42]

毫無疑問,文藝復興運動在洛倫佐掌權之前就已經在開展了。實際上,這場運動開始的時間早在梅第奇家族主宰佛羅倫斯社會之前。有歷史學家猜測,佛羅倫斯之所以成為文藝復興的發源地完全是出於運氣,即,僅僅是因為那些「偉人」恰好都出生在那裡【40】——達文西、波提切利和米開朗基羅都是托斯卡納人。其他歷史學家則認為運氣的說法很難成立,他們斷言當時只有佛羅倫斯的文化環境能使那些「偉人」脫穎而出。

特徵[編輯]

人文主義[編輯]

In some ways Humanism was not a philosophy per se, but rather a method of learning. In contrast to the medieval scholastic mode, which focused on resolving contradictions between authors, humanists would study ancient texts in the original, and appraise them through a combination of reasoning and empirical evidence. Humanist education was based on the programme of 'Studia Humanitatis', that being the study of five humanities: poetry, grammar, history, moral philosophy and rhetoric. Although historians have sometimes struggled to define humanism precisely, most have settled on "a middle of the road definition... the movement to recover, interpret, and assimilate the language, literature, learning and values of ancient Greece and Rome".[43] Above all, humanists asserted "the genius of man ... the unique and extraordinary ability of the human mind."[44] 在某些方面人文主義本身不能算作是一種哲學體系,而更像是一種學習方法。對比中世紀的學術模式,人文主義者並不把焦點放在分析對比不同作家間的矛盾衝突,他們轉而去研究古典文學的起源,通過將推理和經驗證據相綜合的方式對作家作品進行評價。人文主義教育建立在「人文研究」課程之上,對包括詩歌、文法、歷史、倫理和修辭在內的五門學科進行研究。儘管歷史學家有時也對人文主義的準確定義莫衷一是,但大多數人給出的答案是「人們能夠普遍接受這樣的定義……這是一場恢復、詮釋並消化吸收語言、文學、學識和古希臘、古羅馬價值觀的運動。」【42】更為重要的是, 「人的稟賦,人類所獨有的超凡思維能力」是人文主義者堅信不疑的。【43】

Humanist scholars shaped the intellectual landscape throughout the early modern period. Political philosophers such as Niccolò Machiavelli and Thomas More(1478 – 1535) revived the ideas of Greek and Roman thinkers, and applied them in critiques of contemporary government. Machiavelli's contribution, in the view of Isaiah Berlin, was a decisive break in western political thought allocating a unique reasoning to politics and faith and perhaps making him the father of the social sciences. Pico della Mirandola who lived to only twenty-three years wrote what is often considered the manifesto of the Renaissance, a vibrant defence of thinking, the Oration on the Dignity of Man. Matteo Palmieri (1406-1475), another humanist, is most known for his work Della vita civile ("On Civic Life"; printed 1528) which advocated civic humanism, and his influence in refining the Tuscan vernacular to the same level as Latin. Palmieri's written works drawn on Roman philosophers and theorists, especially Cicero, who, like Palmieri, lived an active public life as a citizen and official, as well as a theorist and philosopher and also Quintilian. Strongly committed to a deep and broad education Palmieri believed this would dispose people to public engagement and enhance the human capacity to do good deeds and contribute to the community. Although holding public office between 1432 and 1475 he is best remembered for these writings extolling the ideal of humanism as combination of learning with civic or political action. Possibly the most succinct expression of his perspective on humanism is in a 1465 poetic work La città di vita, but an earlier work Della vita civile (On Civic Life) is more wide-ranging. Composed as a series of dialogues set in a country house in the Mugello countryside outside Florence during the plague of 1430, Palmieri expounds on the qualities of the ideal citizen. The dialogues concern how children develop mentally and physically, how citizens can conduct themselves morally, how citizens and states can ensure probity in public life, and an important debate on the difference between that which is pragmatically useful and that which is honest. 人文主義學者構建起的思想藍圖貫穿了整個近代史。包括馬基雅維利和托馬斯•摩爾(1478-1535)在內的政治哲學家重新激活了古希臘羅馬思想家的觀點,並將其應用於評論當時的政府。從以賽亞•伯林的觀點來看,馬基雅維利的貢獻在於他打破了將某一特定理由賦予政治與信仰的西方政治觀念,他也許因此成為了社會科學的始祖。米蘭多拉在他23歲時完成了通常被認為是文藝復興宣言的《演講之高貴的人》一文,是對當時思想有力的辯駁。馬特奧•佩梅力(1406-1475)也是一位人文主義者,他以《論市民生活》(印刷於1528年)一書最富盛名。書中所倡導的城市人文主義,以及他對托斯卡納地區方言的淨化所產生的影響使其提高到了和拉丁語同等的地位。佩梅力的作品以古羅馬時期的哲學家和理論家為依據,尤其是西塞羅,他和佩梅力一樣一邊擔任公職一邊過著積極的市民生活,但又身兼哲學家和理論家,同樣也包括昆體良。佩梅力致力於擴展教育的深度和廣度,他相信這將會幫助人們更多的參與公共活動,做更多有益的事,並為社會做出貢獻。雖然在1432-1475這十幾年裡佩梅力在政府擔任公職,但人們記住更多的還是他那些讚頌人性理想的作品,其中綜合了對市民行為以及政治行為的研究。也許最能表現佩梅力人文主義觀念的簡明話語出現在他1465年的詩作《動感之都》當中,但更早的《論市民生活》一書的影響範圍則更廣。該書中,作者將場景設置在了1430黑死病瘟疫期間一個位於佛羅倫斯市之外名為穆傑羅的鄉村,在這裡以對話的方式探討了一系列典型好市民應具備的品質。對話涉及兒童心智和體質教育,市民道德行為規範,以及市民和政府如何在公共生活上保持正直廉潔等等,書中還就實用和誠實的概念進行了重要的議論。

藝術[編輯]

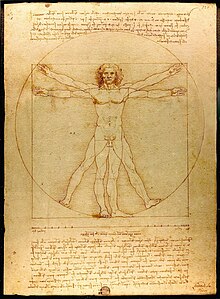

米開朗基羅的創造亞當

One of the distinguishing features of Renaissance art was its development of highly realistic linear perspective. Giotto di Bondone (1267–1337) is credited with first treating a painting as a window into space, but it was not until the demonstrations of architect Filippo Brunelleschi (1377–1446) and the subsequent writings of Leon Battista Alberti (1404–1472) that perspective was formalized as an artistic technique.[45] The development of perspective was part of a wider trend towards realism in the arts.[46] To that end, painters also developed other techniques, studying light, shadow, and, famously in the case of Leonardo da Vinci, human anatomy. Underlying these changes in artistic method, was a renewed desire to depict the beauty of nature, and to unravel the axioms of aesthetics, with the works of Leonardo, Michelangelo and Raphael representing artistic pinnacles that were to be much imitated by other artists.[47] Other notable artists include Sandro Botticelli, working for the Medici in Florence, Donatello another Florentine and Titian in Venice, among others. 文藝復興的明顯特徵之一就是高度寫實的直線透視法的發展。(喬托•迪•邦多納)(1267至1337)被認為是第一個將繪畫看作表達空間的窗口的人,但是,直到有了菲利波•布魯內列斯基(1377至1446)的示範和利昂納•巴蒂斯塔•阿爾貝蒂)(1404至1472)隨後的作品,透視法才作為一種藝術技巧正式確定其地位。透視法的發展構成了更大藝術[45]趨勢下寫實主義發展的一部分。因此,畫家還要發展別的技巧,並研究光和影以及人體解剖學(最有名的例子是萊奧納多•達•芬奇)。引起藝術方法的這些變化的根本原因是人們再次渴望描繪自然之美,弄清楚美學原理,萊奧納多•米開朗基羅和拉斐爾的作品說明了這些原因,代表了藝術的頂點,他們的作品被眾多其他的藝術家[46]所模仿。在其他值得注意的藝術家包括為佛羅倫斯的梅迪契家族工作的桑德羅•波提切利,佛羅倫斯人多納泰羅和威尼斯的提香。

Concurrently, in the Netherlands, a particularly vibrant artistic culture developed, the work of Hugo van der Goes and Jan van Eyck having particular influence on the development of painting in Italy, both technically with the introduction of oil paint and canvas, and stylistically in terms of naturalism in representation. (For more, see Renaissance in the Netherlands). Later, the work of Pieter Brueghel the Elder would inspire artists to depict themes of everyday life.[48] 同時,在荷蘭發展形成了一種極充滿活力的藝術文化,代表是雨果•梵•德爾和揚•凡•愛克的作品,他們對義大利繪畫的發展有特別的影響,在技巧上都引入了油畫顏料和油畫布,在風格上都表現自然主義。(更多內容參見荷蘭的文藝復興部分)。之後的布勒哲爾的作品則激勵藝術家去表現日常生活的主題。

In architecture, Filippo Brunelleschi was foremost in studying the remains of ancient classical buildings, and with rediscovered knowledge from the 1st-century writer Vitruvius and the flourishing discipline of mathematics, formulated the Renaissance style which emulated and improved on classical forms. Brunelleschi's major feat of engineering was the building of the dome of Florence Cathedral.[49] The first building to demonstrate this is claimed to be the church of St. Andrew built by Alberti in Mantua. The outstanding architectural work of the High Renaissance was the rebuilding of St. Peter's Basilica, combining the skills of Bramante, Michelangelo, Raphael, Sangallo and Maderno.

在建築方面,菲利波•布魯內萊斯基在研究古代古典建築遺蹟方面表現最傑出,他從一世紀的作家維特魯威和蓬勃發展的數學學科中重新發現知識,闡述了文藝復興風格,這個風格模仿並改善了古典形式。布魯內萊斯基在工程方面的主要功績就是建造了佛羅倫斯大教堂。[48]第一座表現該風格的建築物據說是曼圖亞的阿爾貝蒂建造的聖安德魯教堂。文藝復興高潮期最傑出的建築作品成果是聖彼得教堂的重建,它融合了布拉曼特、米開朗基羅、拉斐爾、桑迦洛和馬代爾諾的技巧。

The Roman orders types of columns are used: Tuscan, Doric, Ionic, Corinthian and Composite. These can either be structural, supporting an arcade or architrave, or purely decorative, set against a wall in the form of pilasters. During the Renaissance, architects aimed to use columns, pilasters, and entablatures as an integrated system. One of the first buildings to use pilasters as an integrated system was in the Old Sacristy (1421–1440) by Filippo Brunelleschi.[50]

使用了羅馬柱型:托斯卡那型、多利安式、愛奧尼亞式、科林斯式和混合式。這些柱型或者在結構上支撐一個拱廊或框緣,或單純用於裝飾,以壁柱形式靠在牆上。在文藝復興時期,建築師將圓柱、壁柱和柱上楣構作為完整的體系來使用。最早將壁柱作為完整體系來使用的建築物之一是菲利波•布魯內萊斯基[49]建的舊聖器室(1421–1440)。

Arches, semi-circular or (in the Mannerist style) segmental, are often used in arcades, supported on piers or columns with capitals. There may be a section of entablature between the capital and the springing of the arch. Alberti was one of the first to use the arch on a monumental. Renaissance vaults do not have ribs. They are semi-circular or segmental and on a square plan, unlike the Gothic vault which is frequently rectangular.

在拱廊中經常使用拱形、半圓或(風格主義中)弓形結構,這樣的拱廊支撐在扶垛或帶頂的圓柱之上。在柱頂和拱形的起拱點之間可能存在柱上楣構的部分。阿爾貝蒂是最早在紀念碑中使用拱形的建築師之一。文藝復興時期的拱頂沒有拱肋。他們是半圓或弓形的,位於一個方形平面中,不同於通常為矩形的哥德式拱頂。

科學[編輯]

The upheavals occurring in the arts and humanities were mirrored by a dynamic period of change in the sciences. Some have seen this flurry of activity as a "scientific revolution", heralding the beginning of the modern age.[51] Others have seen it merely as an acceleration of a continuous process stretching from the ancient world to the present day.[52] Regardless, there is general agreement that the Renaissance saw significant changes in the way the universe was viewed and the methods with which philosophers sought to explain natural phenomena.[53]

在藝術和人文領域發生劇變的同時,文藝復興時期的科學領域也經歷著相當活躍的變化。有的人認為,這樣急速的變革是一次「科學的革命」,預示著近代的開始。另一些人則認為,這僅僅是古代科學延續下來的某些過程在加速發展。不論如何,大多數人都承認,文藝復興時期的人看待宇宙的方式發生了很大的變化,哲學家們用以解釋某些自然現象的方法也因此發生改變。

伽利略 伽利雷的蠟筆畫像 作者雷奧尼

Science and art were very much intermingled in the early Renaissance, with artists such as Leonardo da Vinci making observational drawings of anatomy and nature. An exhaustive 2007 study by Fritjof Capra [54] shows that Leonardo was a much greater scientist than previously thought, and not just an inventor. In science theory and in conducting actual science practice, Leonardo was innovative. He set up controlled experiments in water flow, medical dissection, and systematic study of movement and aerodynamics; he devised principles of research method that for Capra classify him as 「father of modern science」. In Capra's detailed assessment of many surviving manuscripts Leonardo's science is more in tune with holistic non-mechanistic and non-reductive approaches to science which are becoming popular today. Perhaps the most significant development of the era was not a specific discovery, but rather a process for discovery, the scientific method.[53] This revolutionary new way of learning about the world focused on empirical evidence, the importance of mathematics, and discarding the Aristotelian "final cause" in favor of a mechanical philosophy. Early and influential proponents of these ideas included Copernicus and Galileo. In his 1991 survey of these developments, Charles Van Doren [55] considers that the Copernican revolution really is the Galilean cartesian (René Descartes) revolution, on account of the nature of the courage and depth of change their work brought about.

科學與藝術在文藝復興初期密不可分。畫家雷奧納多達文西就曾經畫過解剖學和自然方面的觀察圖。2007年福特耶夫卡普拉的研究充分表明,達文西不僅僅是一位發明家,他實際上還是一位比過去認為的出色得多的科學家。在科學理論和實際科學試驗方面,達文西都很有創造力。 他對水的流動、醫學解剖進行了可控的實驗,並且系統地研究了物體運動和空氣動力學。他還提出了科學研究的幾項基本原則,卡普拉因此把他稱作「近代科學之父」。根據卡普拉對現存的數張手稿的分析,達文西的科學研究其實更加貼近於整體性的非機制和非推導的方式,這種方式在今天日益流行起來。也許那個時代最重要的進步不是某個特定的科學發現,而是整個發現的過程,也就是研究方法的變革。新的認識世界的方法注重經驗上的證據以及數學的重要性。它拋棄了亞里斯多德的「目的因」學說,轉而支持機械理論。哥白尼和伽利略都是早期支持這些觀點並具影響力的學者。在查爾斯范德倫1991年對這些進步所作的調查中發現,從他們的改革所帶來的鼓舞和改革的深度上來看,哥白尼式的改革實際上是伽利略笛卡爾式改革。

The new scientific method led to great contributions in the fields of astronomy, physics, biology, and anatomy. With the publication of Vesalius's De humani corporis fabrica, a new confidence was placed in the role of dissection, observation, and a mechanistic view of anatomy.[53]

新的科學研究方法帶來了天文、物理,生物和解剖學領域一系列的進步。維薩劉斯的《人體結構研究》這部著作的出版,為解剖、觀測和機械理論的解剖學帶來了新的希望。

宗教[編輯]

The new ideals of humanism, although more secular in some aspects, developed against a Christian backdrop, especially in the Northern Renaissance. Indeed, much (if not most) of the new art was commissioned by or in dedication to the Church.[14] However, the Renaissance had a profound effect on contemporary theology, particularly in the way people perceived the relationship between man and God.[14] Many of the period's foremost theologians were followers of the humanist method, including Erasmus, Zwingli, Thomas More, Martin Luther, and John Calvin.

儘管在某些方面有些世俗,人文主義的構想在基督教的背景之下還是成長起來,在歐洲北部地區尤甚。事實上,絕大多數新創作的藝術作品是受教堂的指派創作,或是獻給教堂的。然而,文藝復興卻對當代神學,尤其是如何看待人與神之間的關係上,產生了深遠的影響。許多那個年代的神學領袖都是人文學派的支持者,包括伊拉茲瑪斯,茨溫利,托馬斯摩爾,馬丁路德,以及約翰加爾文。

亞歷山大四世,一位博基亞家族的教皇,以貪污受賄而聞名

The Renaissance began in times of religious turmoil. The late Middle Ages saw a period of political intrigue surrounding the Papacy, culminating in the Western Schism, in which three men simultaneously claimed to be true Bishop of Rome.[56] While the schism was resolved by the Council of Constance (1414), the 15th century saw a resulting reform movement know as Conciliarism, which sought to limit the pope's power. Although the papacy eventually emerged supreme in ecclesiastical matters by the Fifth Council of the Lateran (1511), it was dogged by continued accusations of corruption, most famously in the person of Pope Alexander VI, who was accused variously of simony, nepotism and fathering four illegitimate children whilst Pope, whom he married off to gain more power.[57]

文藝復興在宗教混亂時期興起。中世紀晚期,羅馬教皇統治混亂,一度曾有三人同時聲稱自己才是真正的羅馬主教教會分裂,西方教會分裂達到頂峰。1414年簽署的康斯坦茲協議最終解決了教會分裂的問題。15世界,議會主義改革星期,旨在限制大主教的權力。儘管第五屆拉特蘭議會最終確定了羅馬教皇在宗教事務中的最高地位,它隨即持續指責教皇的貪污行為。其中最出名的亞歷山大四世,被指控褻瀆聖位,重用親戚,並非法生了四個孩子,他還出嫁女兒,以獲得更多的權力。

Churchmen such as Erasmus and Luther proposed reform to the Church, often based on humanist textual criticism of the New Testament.[14] Indeed, it was Luther who in October 1517 published the 95 Theses, challenging papal authority and criticizing its perceived corruption, particularly with regard to its sale of indulgences. The 95 Theses led to the Reformation, a break with the Roman Catholic Church that previously claimed hegemony in Western Europe. Humanism and the Renaissance therefore played a direct role in sparking the Reformation, as well as in many other contemporaneous religious debates and conflicts.

傳教士們贊成依據新約中對人文主義的評論條文對教堂進行改革,如伊拉茲瑪斯和馬丁路德。實際上,馬丁路德於1517年10月發表的《95條論綱》才真正動搖了教皇的權威地位,批判了它顯而易見的腐敗,尤其是用金錢來免罪的行為。《95條論綱》引發了宗教革命,打破了羅馬天主教堂早先在西歐範圍內宣稱的霸權地位。人文主義和文藝復興因此成為宗教革命以及其他許多同一時期宗教辯論和衝突的導火索。

自我意識[編輯]

By the 15th century, writers, artists and architects in Italy were well aware of the transformations that were taking place and were using phrases like modi antichi (in the antique manner) or alle romana et alla antica (in the manner of the Romans and the ancients) to describe their work. The term la rinascita first appeared, however, in its broad sense in Giorgio Vasari's Vite de' più eccellenti architetti, pittori, et scultori Italiani (The Lives of the Artists, 1550, revised 1568).[58][59] Vasari divides the age into three phases: the first phase contains Cimabue, Giotto, and Arnolfo di Cambio; the second phase contains Masaccio, Brunelleschi, and Donatello; the third centers on Leonardo da Vinci and culminates with Michelangelo. It was not just the growing awareness of classical antiquity that drove this development, according to Vasari, but also the growing desire to study and imitate nature.[60]

15世紀,義大利的作家,藝術家,建築師們充分意識到正在發生的一些變革。那就是他們正在運用古老的方式或採用羅馬人和先人們的習慣來創作自己的作品。 第一次出現了la rinascita的術語。然而,從廣義上來說,喬治 瓦薩里在他的作品de' più eccellenti architetti, pittori, et scultori Italiani(藝術家的生活,1550,1568修訂)[57][58],將這個時期分為三個階段。 第一個階段的代表人物包括:契馬布埃,喬托和阿諾爾弗 迪 坎比奧;第二個階段的代表人物包括馬薩喬,布魯內勒斯基和多納泰羅;第三個階段的代表人物以列奧那多 達 芬奇為焦點,米開朗基羅則將這一時期藝術作品推向高潮。 據瓦薩里記載,文藝復興運動的發展,不僅僅是因為人們對傳統文化藝術的意識日益俱增,而且還因為人們學習和模仿大自然的意願不斷增強。

傳播[編輯]

In the 15th century, the Renaissance spread with great speed from its birthplace in Florence, first to the rest of Italy, and soon to the rest of Europe. The invention of the printing press allowed the rapid transmission of these new ideas. As it spread, its ideas diversified and changed, being adapted to local culture. In the 20th century, scholars began to break the Renaissance into regional and national movements. 15世紀,文藝復興運動從發源地佛羅倫斯迅速蔓延開來,首先傳播到義大利其它地方,很快滲入到整個歐洲其它地區。印刷機的發明使得這些新思想迅速得以傳播。在傳播過程中,這些思想融合了地方文化,呈現出多樣性。 20世紀,學者們開始撇開文藝復興,提倡開展地方和民族文化運動。

北歐文藝復興[編輯]

The Renaissance as it occurred in Northern Europe has been termed the "Northern Renaissance".

匈牙利[編輯]

The Renaissance style came directly from Italy during the Quattrocento to Hungary first in the Central European region, thanks to the development of early Hungarian-Italian relationships – not only in dynastic connections, but also in cultural, humanistic and commercial relations – growing in strength from the 1300s. Italian architectural influence became stronger in the reign of Zsigmond thanks to the church foundations of the Florentine Scolaries and the castle constructions of Pipo of Ozora. The relationship between Hungarian and Italian Gothic styles was a second reason – exaggerated breakthrough of walls is avoided, preferring clean and light structures. The new Italian trend combined with existing national traditions to create a particular local Renaissance art. Acceptance of Renaissance art was furthered by the continuous arrival of humanist thought in the country. Many young Hungarians studying at Italian universities came closer to the Florentine humanist center, so a direct connection with Florence evolved. The growing number of Italian traders moving to Hungary, specially to Buda, helped this process. New thoughts were carried by the humanist prelates, among them Vitéz János, archbishop of Esztergom, one of the founders of Hungarian humanism.[61] After the marriage in 1476 of Matthias Corvinus (King of Hungary from 1458-1490) to Beatrice of Naples, Buda became one of the most important artistic centres of the Renaissance north of the Alps.[62] The most important humanists living in Matthias' court were Antonio Bonfini and the famous Hungarian poet Janus Pannonius.[62] Matthias Corvinus's library, the Bibliotheca Corviniana, was Europe's greatest collections of secular books: historical chronicles, philosophic and scientific works in the fifteenth century. His library was second only in size to the Vatican Library. (However, the Vatican Library mainly contained Bibles and religious materials.)[63] In 1489, Bartolomeo della Fonte of Florence wrote that Lorenzo de Medici founded his own Greek-Latin library encouraged by the example of the Hungarian king. Corvinus's library is part of UNESCO World Heritage.[64] Other important figures of Hungarian Renaissance: Bálint Balassi (poet) , Sebestyén Tinódi Lantos (poet), Bálint Bakfark (composer and lutenist) 歐洲文藝復興初期,由於早期匈-意關係的發展,如皇族間的交流,以及在文化,人文和商業之間的聯繫,文藝復興時期的風格首先從義大利直接傳播到位於中歐地區的匈牙利。其影響從13世紀開始逐漸發展壯大。 由於佛羅倫斯Scolaries教堂以及Pipo of Ozora.城堡的建立,義大利建築風格在Zsigmond統治時期日益盛行起來。匈牙利和義大利哥德式建築風格關係密切是第二個原因-避免使用誇張,突兀的牆壁,而喜歡採用清新,明亮的建築結構。新的義大利風格融合了匈牙利現有的民族傳統,創造出一種獨特的,具有地方特色的文藝復興藝術作品。伴隨著整個國家人文思想的興起,文藝復興藝術受到進一步推崇。 許多在義大利大學求學的匈牙利年青人奔向佛羅倫斯人文中心,於是直接受到佛羅倫斯人文思想的影響。 越來越多的義大利商人來到匈牙利,特別是布達,促進了文藝復興的加速傳播。人文主義高級神職人員將新思想傳播開來,其中包括埃斯泰爾戈姆大主教Vitéz János,他是匈牙利人文主義思想的創始人之一。1476年,匈牙利國王(1458-1490)馬加什·科韋努斯與那不勒斯的比阿特麗斯聯姻之後,布達成為阿爾卑斯山北部地區文藝復興的重要藝術中心。馬加什當政期間最重要的人文思想家包括安東尼奧· 本菲尼和著名的匈牙利詩人傑納斯 ·潘納尼爾斯。15世紀, 馬加什·科韋努斯的圖書館,科韋努斯圖書館擁有歐洲最大的非宗教類藏書, 歷史志,哲學和科學作品 他的圖書館規模僅次於梵蒂岡圖書館,(然而,梵蒂岡圖書館主要收藏聖經和宗教類書籍)1489年佛羅倫斯Bartolomeo della Fonte寫道:受匈牙利國王的鼓舞,Lorenzo de Medici也建立了自己的希臘語-拉丁語圖書館。科韋努斯的圖書館成為聯合國科教文組織世界文化遺產的一部分。匈牙利文藝復興時期的其它重要人物還包括 Bálint Balassi (詩人) , Sebestyén Tinódi Lantos(詩人),Bálint Bakfark (作曲家和琵琶彈奏者)

波蘭[編輯]

喬瓦尼·巴蒂斯塔在1550—1555年按照哥德式風格重建波南茲市廳

An early Italian humanist who came to Poland in the mid-15th century was Filip Callimachus. Many Italian artists came to Poland with Bona Sforza of Milan, when she married King Zygmunt I of Poland in 1518.[65] This was supported by temporarily strengthened monarchies in both areas, as well as by newly-established universities.[66] 在15世紀中期較早來到波蘭的義大利人文主義者是菲利普·卡利馬庫斯。1518年,當米蘭的博納·斯福爾扎嫁給波蘭國王齊格蒙德一世時,許多義大利藝術家都跟隨她來到波蘭。當時兩地強化了的君主統治以及新建立的大學推動了此舉。

德國[編輯]

In the second half of the 15th century, the spirit of the age spread to Germany and the Low Countries, where the development of the printing press (ca. 1450) and early Renaissance artists like the painters Jan van Eyck (1395-1441) and Hieronymus Bosch (1450-1516) and the composers Johannes Ockeghem (1410-1497), Jacob Obrecht (1457-1505) and Josquin des Prez (1455-1521), predated the influence from Italy. In the early Protestant areas of the country humanism became closely linked to the turmoil of the Protestant Reformation, and the art and writing of the German Renaissance frequently reflected this dispute.[67] However, the gothic style and medieval scholastic philosophy remained exclusively until the turn of the 16th century. Emperor Maximilian I (Ruling:1493-1519) was the first truly Renaissance monarch of the Holy Roman Empire. 15世紀後半葉,時代精神傳播到德國和低地國家,在這些地方印刷機與文藝復興早期藝術家,如畫家揚·范·艾克,希羅尼穆斯·博斯,作曲家約翰內斯·奧克岡,若斯坎·德普雷,雅各布·奧布雷赫特的發展(不舒服,機器和人並列)早於來自義大利的影響。在該國新教地區,早期人們將人文主義與新教改革的騷亂緊密聯繫在一起,德國的藝術與寫作經常反映這場爭辯。然而,直到十六世紀之交,哥德式風格與中世紀經院哲學開始成為主導。皇帝馬克西米連一世(1493-1519年在位)是第一個真正意義上的神聖羅馬帝國文藝復興時期的君王。

法國[編輯]

In 1495 the Italian Renaissance arrived in France, imported by King Charles VIII after his invasion of Italy. A factor that promoted the spread of secularism was the Church's inability to offer assistance against the Black Death. Francis I imported Italian art and artists, including Leonardo da Vinci, and built ornate palaces at great expense. Writers such as François Rabelais, Pierre de Ronsard, Joachim du Bellay and Michel de Montaigne, painters such as Jean Clouet and musicians such as Jean Mouton also borrowed from the spirit of the Italian Renaissance.

1495年,法國國王查理八世入侵義大利後,將義大利的文藝復興引入了法國。教會面對黑死病疫情的束手無策也是促進世俗主義的傳播的一大因素。弗朗索瓦一世給法國帶來了義大利的藝術和達文西等藝術家,他還花重金建造了華麗的宮殿。法國作家拉伯雷、德龍沙、杜·貝萊和蒙田,畫家讓·克盧埃以及音樂家讓·穆東等人都借鑑了義大利的文藝復興精神。

In 1533, a fourteen-year old Caterina de' Medici, (1519–1589) born in Florence to Lorenzo II de' Medici and Madeleine de la Tour d'Auvergne married Henry, second son of King Francis I and Queen Claude. Though she became famous and infamous for her role in France's religious wars, she made a direct contribution in bringing arts, sciences and music (including the origins of ballet) to the French court from her native Florence.

1533年,洛倫佐二世·德·梅第奇把他14歲的女兒卡特里娜·德·梅第奇嫁給了後來的法國國王亨利二世。雖然卡特里娜由於她在法國宗教戰爭中的角色而臭名昭著,她對於將藝術、科學、音樂(包括芭蕾的開端)從她的家鄉佛羅倫斯引進法國宮廷卻做出了直接的貢獻。

英格蘭[編輯]

人是何等巧妙的一件天工!理性何等的高貴!智能何等的廣大!儀容舉止是何等的勻稱可愛!行動是多麼像天使!悟性是多麼像神明!真是世界之美,萬物之靈!【這段是梁實秋先生的譯文】(威廉·莎士比亞《哈姆雷特》這些引語突出人類是宇宙的中心)

In England, the Elizabethan era marked the beginning of the English Renaissance with the work of writers William Shakespeare, Christopher Marlowe,Edmund Spenser , Sir Thomas More , Francis Bacon , Sir Philip Sidney ,John Milton (who is known as perhaps last of the renaissance artists), as well as great artists, architects (such as Inigo Jones who introduced Italianate architecture to England), and composers such as Thomas Tallis, John Taverner, and William Byrd.

在英格蘭,伊莉莎白時代標誌著英格蘭文藝復興的開端,那時流行著作家莎士比亞,克里斯多福·馬洛,埃德蒙·斯賓塞,托馬斯·莫爾,培根,菲利普·西德尼,米爾頓(他被認為是文藝復興時期最後一個藝術家),許多的藝術家,包括建築師(例如將義大利式建築引進英國的伊尼戈·瓊斯)和作曲家,例如托馬斯·塔利斯,約翰·塔弗納,威廉·伯德。

Southern Europe[編輯]

Italy[編輯]

While Renaissance ideas were moving north from Italy, there was a simultaneous southward spread of some areas of innovation, particularly in music.[68] The music of the 15th century Burgundian School defined the beginning of the Renaissance in that art and the polyphony of the Netherlanders, as it moved with the musicians themselves into Italy, formed the core of what was the first true international style in music since the standardization of Gregorian Chant in the 9th century.[68] The culmination of the Netherlandish school was in the music of the Italian composer, Palestrina. At the end of the 16th century Italy again became a center of musical innovation, with the development of the polychoral style of the Venetian School, which spread northward into Germany around 1600.

The paintings of the Italian Renaissance differed from those of the Northern Renaissance. Italian Renaissance artists were among the first to paint secular scenes, breaking away from the purely religious art of medieval painters. At first, Northern Renaissance artists remained focused on religious subjects, such as the contemporary religious upheaval portrayed by Albrecht Dürer. Later on, the works of Pieter Bruegel influenced artists to paint scenes of daily life rather than religious or classical themes. It was also during the northern Renaissance that Flemish brothers Hubert and Jan van Eyck perfected the oil painting technique, which enabled artists to produce strong colors on a hard surface that could survive for centuries.[69] A feature of the Northern Renaissance was its use of the vernacular in place of Latin or Greek, which allowed greater freedom of expression. This movement had started in Italy with the decisive influence of Dante Alighieri on the development of vernacular languages; in fact the focus on writing in Italian has neglected a major source of Florentine ideas expressed in Latin.[70] The spread of the technology of the German invention of movable type printing boosted the Renaissance, in Northern Europe as elsewhere; with Venice becoming a world center of printing.

Spain[編輯]

The Renaissance arrived in the Iberian peninsula through the Mediterranean possessions of the Aragonese Crown and the city of Valencia. Indeed, many of the early Spanish Renaissance writers come from the Kingdom of Aragon, including Ausiàs March and Joanot Martorell. In the Kingdom of Castile, the early Renaissance was heavily influenced by the Italian humanism, starting with writers and poets starting with the Marquis of Santillana, who introduced the new Italian poetry to Spain in the early 15th century. Other writers, such as Jorge Manrique, Fernando de Rojas, Juan del Encina, Juan Boscán Almogáver and Garcilaso de la Vega, kept a close resemblance to the Italian canon. Miguel de Cervantes's masterpiece Don Quixote is credited as the first Western novel. Renaissance humanism flourished in the early 16th century, with influential writers such as philosopher Juan Luis Vives, grammarian Antonio de Nebrija or natural historian Pedro de Mexía.

Later Spanish Renaissance tended towards religious themes and mysticism, with poetas such as fray Luis de León, Teresa of Ávila and John of the Cross, and treated issues related to the exploration of the New World, with chroniclers and writers such as Inca Garcilaso de la Vega or Bartolomé de las Casas. The late Renaissance in Spain also saw the rise of artists such as El Greco, and composers such as Tomás Luis de Victoria and Antonio de Cabezón.

Portugal[編輯]

In Portugal, the Renaissance arrived through the influence of the wealthy Italian merchants that started investing their money in the profitable Indian commerce that Portugal had monopolized during the late 15th century. Lisbon flourished, and writers such as Gil Vicente, Sá de Miranda, Bernardim Ribeiro and Luís de Camões and artists such as Nuno Gonçalves appeared.

Historiography[編輯]

Conception[編輯]

The term was first used retrospectively by the Italian artist and critic Giorgio Vasari (1511–1574) in his book The Lives of the Artists (published 1550). In the book Vasari was attempting to define what he described as a break with the barbarities of gothic art: the arts had fallen into decay with the collapse of the Roman Empire and only the Tuscan artists, beginning with Cimabue (1240–1301) and Giotto (1267–1337) began to reverse this decline in the arts. According to Vasari, antique art was central to the rebirth of Italian art.[71]

However, it was not until the nineteenth century that the French word Renaissance achieved popularity in describing the cultural movement that began in the late-13th century. The Renaissance was first defined by French historian Jules Michelet (1798–1874), in his 1855 work, Histoire de France. For Michelet, the Renaissance was more a development in science than in art and culture. He asserted that it spanned the period from Columbus to Copernicus to Galileo; that is, from the end of the 15th century to the middle of the seventeenth century.[72] Moreover, Michelet distinguished between what he called, "the bizarre and monstrous" quality of the Middle Ages and the democratic values that he, as a vocal Republican, chose to see in its character.[9] A French nationalist, Michelet also sought to claim the Renaissance as a French movement.[9]

The Swiss historian Jacob Burckhardt (1818–1897) in his Die Cultur der Renaissance in Italien (1860), by contrast, defined the Renaissance as the period between Giotto and Michelangelo in Italy, that is, the 14th to mid-16th centuries. He saw in the Renaissance the emergence of the modern spirit of individuality, which had been stifled in the Middle Ages.[73] His book was widely read and was influential in the development of the modern interpretation of the Italian Renaissance.[74] However, Buckhardt has been accused of setting forth a linear Whiggish view of history in seeing the Renaissance as the origin of the modern world.[11]

More recently, historians have been much less keen to define the Renaissance as a historical age, or even a coherent cultural movement. As Randolph Starn has put it,

Rather than a period with definitive beginnings and endings and consistent content in between, the Renaissance can be (and occasionally has been) seen as a movement of practices and ideas to which specific groups and identifiable persons variously responded in different times and places. It would be in this sense a network of diverse, sometimes converging, sometimes conflicting cultures, not a single, time-bound culture.[11]

——Randolph Starn

For better or for worse?[編輯]

Much of the debate around the Renaissance has centered around whether the Renaissance truly was an "improvement" on the culture of the Middle Ages. Both Michelet and Burckhardt were keen to describe the progress made in the Renaissance towards the "modern age". Burckhardt likened the change to a veil being removed from man's eyes, allowing him to see clearly.[41]

In the Middle Ages both sides of human consciousness – that which was turned within as that which was turned without – lay dreaming or half awake beneath a common veil. The veil was woven of faith, illusion, and childish prepossession, through which the world and history were seen clad in strange hues.[75]

——Jacob Burckhardt,The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy

On the other hand, many historians now point out that most of the negative social factors popularly associated with the "medieval" period – poverty, warfare, religious and political persecution, for example – seem to have worsened in this era which saw the rise of Machiavelli, the Wars of Religion, the corrupt Borgia Popes, and the intensified witch-hunts of the 16th century. Many people who lived during the Renaissance did not view it as the "golden age" imagined by certain 19th-century authors, but were concerned by these social maladies.[76] Significantly, though, the artists, writers, and patrons involved in the cultural movements in question believed they were living in a new era that was a clean break from the Middle Ages.[58] Some Marxist historians prefer to describe the Renaissance in material terms, holding the view that the changes in art, literature, and philosophy were part of a general economic trend away from feudalism towards capitalism, resulting in a bourgeois class with leisure time to devote to the arts.[77]

Johan Huizinga (1872–1945) acknowledged the existence of the Renaissance but questioned whether it was a positive change. In his book The Waning of the Middle Ages, he argued that the Renaissance was a period of decline from the High Middle Ages, destroying much that was important.[10] The Latin language, for instance, had evolved greatly from the classical period and was still a living language used in the church and elsewhere. The Renaissance obsession with classical purity halted its further evolution and saw Latin revert to its classical form. Robert S. Lopez has contended that it was a period of deep economic recession.[78] Meanwhile George Sarton and Lynn Thorndike have both argued that scientific progress was perhaps less original than has traditionally been supposed.[79]

Some historians have begun to consider the word Renaissance to be unnecessarily loaded, implying an unambiguously positive rebirth from the supposedly more primitive "Dark Ages" (Middle Ages). Many historians now prefer to use the term "Early Modern" for this period, a more neutral designation that highlights the period as a transitional one between the Middle Ages and the modern era.[80] Others such as Roger Osborne have come to consider the Italian Renaissance as a repository of the myths and ideals of western history in general, and instead of rebirth of ancient ideas as a period of great innovation [81]

Other Renaissances[編輯]

The term Renaissance has also been used to define time periods outside of the 15th and 16th centuries. Charles H. Haskins (1870–1937), for example, made a case for a Renaissance of the 12th century.[82] Other historians have argued for a Carolingian Renaissance in the 8th and 9th centuries, and still later for an Ottonian Renaissance in the 10th century.[83] Other periods of cultural rebirth have also been termed "renaissances", such as the Bengal Renaissance or the Harlem Renaissance.

See also[編輯]

- Weser Renaissance

- Gilded woodcarving

- List of Renaissance figures

- List of Renaissance structures

- Medical Renaissance

- Scientific Revolution

References[編輯]

- Brotton, Jerry, The Renaissance: A Very Short Introduction ISBN 0-19-280163-5

- Burckhardt, Jacob (1878), The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy, trans S. G. C. Middlemore, republished in 1990 ISBN 0-14-044534-X

- Burke, P, The European Renaissance: Centre and Peripheries ISBN 0-631-19845-8

- Cronin, Vincent (1967), The Florentine Renaissance ISBN 0002112620

- ------------------(1969), The Flowering of the Renaissance, ISBN 0712698841

- ------------------(1992), The Renaissance, ISBN 0002154110

- Ergang, Robert (1967), The Renaissance, ISBN 0-442-02319-7

- Ferguson, Wallace K. (1962), Europe in Transition, 1300–1500, ISBN 0-04-940008-8

- Haskins, Charles Homer (1927), The Renaissance of the Twelfth Century, ISBN 0-674-76075-1

- Huizinga, Johan (1924), The Waning of the Middle Ages, republished in 1990 ISBN 0-14-013702-5

- Jensen, De Lamar (1992), Renaissance Europe, ISBN 0-395-88947-2

- Lopez, Robert S. (1952), Hard Times and Investment in Culture

- Stephens, John, The Italian Renaissance: The Origins of Intellectual and Artistic Change before the Renaissance ISBN 0-582-49337-4

- Strathern, Paul (2003), The Medici: Godfathers of the Renaissance, ISBN 1844130983

- Thorndike, Lynn (1943) 'Renaissance or Prenaissance?' in "Some Remarks on the Question of the Originality of the Renaissance", Journal of the History of Ideas Vol. 4, No. 1, Jan. 1943 (Subscription required for JSTOR link.)

- Ward, A. The Cambridge Modern History. Vol 1: The Renaissance (1902)

- Weiss, Roberto (1969) The Renaissance Discovery of Classical Antiquity, ISBN 1-597-40150-1

- Werkmeister, William H. [editor]. Facets of the Renaissance. Los Angeles: University of Southern California Press. 1959.

Notes[編輯]

- ^ Renaissance, Online Etymology Dictionary. Etymonline.com. [2009-07-31].

- ^ BBC Science & Nature,Leonardo da Vinci.於2009年12月24日查閱.

- ^ BBC History,Michelangelo.於2009年12月24日查閱.

- ^ Burke, P.,The European Renaissance: Centre and Peripheries(Blackwell,Oxford 1998)

- ^ 5.0 5.1 Strathern, Paul The Medici: Godfathers of the Renaissance (2003)

- ^ Encyclopedia Britannica,Renaissance,2008,O.Ed.

- ^ Har, Michael H.History of Libraries in the Western World,Scarecrow Press Incorporate,1999,ISBN 0810837242.

- ^ Norwich, John Julius,A Short History of Byzantium,1997,Knopf,ISBN 0679450882.

- ^ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Brotton, J.,The Renaissance: A Very Short Introduction,OUP,2006.

- ^ 10.0 10.1 Huizanga, Johan,The Waning of the Middle Ages(1919,trans. 1924).

- ^ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Starn, Randolph. "Renaissance Redux" The American Historical Review Vol.103 No.1 p.124 (Subscription required for JSTOR link)

- ^ The Idea of the Renaissance,Richard Hooker,Washington State University Website.於2009年12月24日查閱.

- ^ Perry, M.Humanities in the Western Tradition,Ch. 13.

- ^ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 Open University,Looking at the Renaissance: Religious Context in the Renaissance.於2009年12月24日查閱. 引用錯誤:帶有name屬性「openuni」的

<ref>標籤用不同內容定義了多次 - ^ Open University,Looking at the Renaissance: Urban economy and government.於2009年12月24日查閱.

- ^ Stark, Rodney,The Victory of Reason,Random House,NY:2005.

- ^ Walker, Paul Robert,The Feud that sparked the Renaissance: How Brunelleschi and Ghiberti Changed the Art World,(New York, Perennial-Harper Collins, 2003).

- ^ 對於早期的這種針對不同古代文獻(科學文獻而不是文學文獻)的不同研究,更詳細的信息參見12世紀的拉丁語翻譯以及伊斯蘭對中世紀歐洲的貢獻.

- ^ L.D. Reynolds and Nigel Wilson,Scribes and Scholars: A guide to the transmission of Greek and Latin Literature Clarendon Press,Oxford,1974,p.113-123.

- ^ L.D. Reynolds and Nigel G. Wilson,Scribes and scholars p. 123;130-137.

- ^ Bèze, Théodore de; Summers, Kirk M. A view from the Palatine: the Iuvenilia of Théodore de Bèze. Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies. 2001: 442. ISBN 0866982795 9780866982795 請檢查

|isbn=值 (幫助).Demetrius Chalcondyles (1423-1511), a Greek refugee who taught Greek at Perugia, Padua, Florence, and Milan. Around 1493 he produced a Greek textbook for beginners.

- ^ Valeriano, Pierio; Gaisser, Julia Haig. Pierio Valeriano on the ill fortune of learned men: a Renaissance humanist and his world. University of Michigan Press. 1999: 281. ISBN 0472110551, 9780472110551 請檢查

|isbn=值 (幫助).Demetrius Chalcondyles was a prominent Greek humanist. He taught Greek in Italy for over forty years.

- ^ L.D. Reynolds and Nigel G. Wilson,Scribes and scholars,.p. 119, 131.

- ^ Demetrius Chalcondyles.. www.britannica.com. [2009-09-24].

Demetrius Chalcondyles – born 1424, Athens [Greece] died 1511, Milan [Italy]. In 1447 Demetrius went to Italy, where Cardinal Bessarion became his patron. He was made professor at Padua in 1463.

- ^ Cubberley, Ellwood Patterson. The History of Education Volume 1. BiblioBazaar, LLC. 2008: 264. ISBN 9780554225234.

Another Greek of importance was Demetrius Chalcondyles of Athens (1424—1511), who reached Italy in 1447. In 1450 he became professor of Greek at Perugia.

- ^ Bèze, Théodore de; Summers, Kirk M. A view from the Palatine: the Iuvenilia of Théodore de Bèze. Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies. 2001: 442. ISBN 0866982795 9780866982795 請檢查

|isbn=值 (幫助).Demetrius Chalcondyles (1423-1511), a Greek refugee who taught Greek at Perugia, Padua, Florence, and Milan. Around 1493 he produced a Greek textbook for beginners.

- ^ Baldassare Castiglione. britannica.com. [2009-12-26].

Castiglione was educated [by] Demetrius Chalcondyles.

- ^ Valeriano, Pierio; Gaisser, Julia Haig. Pierio Valeriano on the ill fortune of learned men: a Renaissance humanist and his world. University of Michigan Press. 1999: 281. ISBN 9780472110551.

Demetrius Chalcondyles was a prominent Greek humanist. He taught Greek in Italy for over forty years; among his pupils were Ianus Lascaris, Poliziano, Leo X, Castaglione, Giraldi, Stefano Negri, and Giovanni Maria Cattaneo.

- ^ Demetrius Chalcondyles.. www.britannica.com. [2009-09-25].

One of his pupils at Florence was the German scholar Johann Reuchlin.

- ^ History of the Renaissance,HistoryWorld.於2009年12月27日查閱.

- ^ Kirshner, Julius,Family and Marriage: A socio-legal perspective,Italy in the Age of the Renaissance: 1300–1550,ed. John M. Najemy (Oxford University Press, 2004) p.89.於2009年12月26日查閱.

- ^ Burckhardt, Jacob,The Revival of Antiquity',The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy(trans. by S.G.C. Middlemore,1878).

- ^ 原文:「the remarkable efflorescence of moral, social and political philosophy that occurred in Florence at the same time」.

- ^ Skinner, Quentin,The Foundations of Modern Political Thought,vol I:The Renaissance;vol II:The Age of Reformation,Cambridge University Press,p. 69.

- ^ Skinner, Quentin,The Foundations of Modern Political Thought,vol I:The Renaissance;vol II:The Age of Reformation,Cambridge University Press,p. 69).

- ^ Stark, Rodney,The Victory of Reason,New York,Random House,2005.

- ^ Martin, J. and Romano, D.,Venice Reconsidered,Baltimore,Johns Hopkins University,2000.

- ^ 38.0 38.1 Burckhardt, Jacob,The Republics: Venice and Florence,The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy,translated by S.G.C. Middlemore,1878.

- ^ 進一步的信息可閱讀芭芭拉·塔奇曼(Barbara Tuchman)的作品《遙遠的鏡子》(A Distant Mirror).

- ^ The End of Europe's Middle Ages: The Black Death,University of Calgary website.於2009年12月27日查閱.

- ^ 41.0 41.1 Burckhardt, Jacob, The Development of the Individual, The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy, translated by S.G.C. Middlemore, 1878.

- ^ Stephens, J., Individualism and the cult of creative personality, The Italian Renaissance, New York, 1990 p. 121.

- ^ Burke, P., The spread of Italian humanism, in The impact of humanism on western Europe, ed. A. Goodman and A. MacKay, London, 1990, p. 2.

- ^ As asserted by Gianozzo Manetti in On the Dignity and Excellence of Man, cited in Clare, J., Italian Renaissance.

- ^ Clare, John D. & Millen, Alan, Italian Renaissance, London, 1994, p. 14.

- ^ Stork, David G. Optics and Realism in Renaissance Art (Retrieved on May 10, 2007)

- ^ Vasari, Giorgio, Lives of the Artists, translated by George Bull, Penguin Classics, 1965, ISBN 0-14-044-164-6.

- ^ Peter Brueghel Biography, Web Gallery of Art (Retrieved on May 10, 2007)

- ^ Hooker, Richard, Architecture and Public Space (Retrieved on May 10, 2007)

- ^ Saalman, Howard. Filippo Brunelleschi: The Buildings. Zwemmer. 1993.

- ^ Butterfield, Herbert, The Origins of Modern Science, 1300–1800, p. viii

- ^ Shapin, Steven. The Scientific Revolution, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996, p. 1.

- ^ 53.0 53.1 53.2 Brotton, J., "Science and Philosophy", The Renaissance: A Very Short Introduction OUP, 2006.

- ^ Capra, Fritjof, The Science of Leonardo; Inside the Mind of the Great Genius of the Renaissance, New York, Doubleday, 2007.

- ^ Van Doren, Charles, A History of Knowledge, New York, Ballantine, 1991.

- ^ Catholic Encyclopedia, Western Schism (Retrieved on May 10, 2007)

- ^ Catholic Encyclopedia, Alexander VI (Retrieved on May 10, 2007)

- ^ 58.0 58.1 Panofsky, Erwin. Renaissance and Renascences in Western Art, New York: Harper and Row, 1960.

- ^ The Open University Guide to the Renaissance, Defining the Renaissance (Retrieved on May 10, 2007)

- ^ Sohm, Philip. Style in the Art Theory of Early Modern Italy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001)

- ^ the influences of the florentine renaissance in hungary. Fondazione-delbianco.org. [2009-07-31].

- ^ 62.0 62.1 Czigány, Lóránt, A History of Hungarian Literature, "The Renaissance in Hungary" (Retrieved on May 10, 2007)

- ^ Marcus Tanner, The Raven King: Matthias Corvinus and the Fate of his Lost Library (New Haven: Yale U.P., 2008)

- ^ [1][失效連結]

- ^ (1494,%E2%80%93,1557),1958.html History of Poland on Polish Government's website (Retrieved on April 4–2007)

- ^ For example, the re-establishment of Jagiellonian University in 1400.

- ^ Review of Lewis Spitz, The Religious Renaissance of the German Humanists. Review by Gerald Strauss, English Historical Review, Vol. 80, No. 314, p.156. Available on JSTOR (subscription required).

- ^ 68.0 68.1 Láng, Paul Henry. "The So Called Netherlands Schools," The Musical Quarterly, Vol. 25, No. 1. (Jan., 1939), pp. 48–59. (Subscription required for JSTOR link.)

- ^ Painting in Oil in the Low Countries and Its Spread to Southern Europe, Metropolitan Museum of Art website. (Retrieved April 5–2007)

- ^ Celenza, Christopher, (2004) The Lost Italian Renaissance: Humanists, Historians, and Latin's Legacy.Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press

- ^ Defining the Renaissance, Open University. Open.ac.uk. [2009-07-31].

- ^ Michelet, Jules. History of France, trans. G. H. Smith (New York: D. Appleton, 1847)

- ^ Burckhardt, Jacob. The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy (trans. S.G.C Middlemore, London, 1878)

- ^ Gay, Peter, Style in History, New York: Basic Books, 1974.

- ^ Burckhardt, Jacob, The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy, [August 31, 2008]

- ^ Savonarola's popularity is a prime example of the manifestation of such concerns. Other examples include Phillip II of Spain's censorship of Florentine paintings, noted by Edward L. Goldberg, "Spanish Values and Tuscan Painting", Renaissance Quarterly (1998) p.914

- ^ Renaissance Forum at Hull University, Autumn 1997 (Retrieved on 10-05-2007)

- ^ Lopez, Robert S., and Miskimin, Harry A., The Economic Depression of the Renaissance, Economic History Review, 2nd ser., 14 (1962), pp. 408-26. Available on JSTOR (subscription required)

- ^ Thorndike, Lynn (1943) Renaissance or Prenaissance? in "Some Remarks on the Question of the Originality of the Renaissance", Journal of the History of Ideas Vol. 4, No. 1, Jan. 1943. Available on JSTOR (subscription required)

- ^ Greenblatt, S. Renaissance Self-Fashioning: From More to Shakespeare, University of Chicago Press, 1980.

- ^ Osborne, Roger, Civilization: a new history of the Western world, Pegasus Books, 2006.

- ^ Haskins, Charles Homer, The Renaissance of the Twelfth Century, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1927.

- ^ Hubert, Jean, L』Empire carolingien, (English: The Carolingian Renaissance, translated by James Emmons, New York: G. Braziller, 1970.

External links[編輯]

維基共享資源上的相關多媒體資源:PhiLiP/文藝復興 本頁面的朗讀版本([[:Image:|資訊/下載]])

[[Image:|200px|center]] 此音訊檔案是根據條目「PhiLiP/文藝復興」2006-12-05的修訂版本錄製的,以[[]]朗讀,不會反映對該頁面的後續編輯。(媒體幫助)

|

- Ancient and Renaissance women by Dr. Deborah Vess

- Notable Medieval and Renaissance Women

- Renaissance Style Guide

- Interactive Resources

- Florence: 3D Panoramas of Florentine Renaissance Sites(English/Italian)

- Interactive Glossary of Terms Relating to the Renaissance

- Multimedia Exploration of the Renaissance

- RSS News Feed: Get an entry from Leonardo's Journal delivered each day

- Virtual Journey to Renaissance Florence

- Exhibits Collection - Renaissance

- Lectures and Galleries

Template:Renaissance navbox Template:Periods of the History of Europe

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||