User:如沐西风/SandboxM

| 這是維基百科用户页 此頁面不是百科全書條目,也不是條目的讨论页。 若您在中文維基百科(域名為zh.wikipedia.org)之外的网站看到此頁面,那麼您可能正在瀏覽一个镜像网站。 请注意:镜像网站中的页面可能已经过时,且页面中涉及的用户可能與该镜像網站沒有任何关系。 若欲造訪原始页面,請點擊这里。 |

| 建筑沙盒 现在条目:贝聿铭 外文版本:en:I. M. Pei(特色条目评选时的版本) 辅助工具:User:如沐西风/遗珍计划、维基百科:中国文化遗产专题、{{山西文保}}、{{文物保护单位}} 备注:不需要完全依照英文版本。可根据需要增删内容;英文版配图质量令人失望 |

| 貝聿銘 貝聿銘 | |

|---|---|

2006年摄于卢森堡 | |

| 出生 | 1917年4月26日 |

| 逝世 | 2019年5月16日(102歲) |

| 公民权 | Republic of China United States |

| 职业 | 建筑师 |

| 配偶 | Eileen Loo (1942年结婚—2014年丧偶) |

| 儿女 | 4 |

| 奖项 | Royal Gold Medal AIA Gold Medal Presidential Medal of Freedom Pritzker Prize Praemium Imperiale |

| 事务所 | I. M. Pei & Associates 1955–2019 I. M. Pei & Partners 1966–2019 Pei Cobb Freed & Partners 1989–2019 Pei Partnership Architects (consultant) 1992–2019 |

| 建筑 | John F. Kennedy Library, Boston National Gallery of Art East Building Louvre Pyramid, Paris Bank of China Tower, Hong Kong Museum of Islamic Art, Doha Indiana University Art Museum Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Miho Museum, The chapel of a junior and high school : Miho Institute of Aesthetics, Japan |

| 如沐西风/SandboxM | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 繁体字 | 貝聿銘 | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 简化字 | 贝聿铭 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 遗珍 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 缪斯 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 丝路/西洋 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 蹴鞠 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 察罕 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 时事 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 工具箱 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

C & P 链接翻译 WP:译音表 User:如沐西风/遗珍计划 User:胡葡萄/方志资源 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Ieoh Ming Pei, FAIA, RIBA[1] (26 April 1917 – 16 May 2019) was a Chinese-American architect. Born in Guangzhou and raised in Hong Kong and Shanghai, Pei drew inspiration at an early age from the gardens at Suzhou. In 1935, he moved to the United States and enrolled in the University of Pennsylvania's architecture school, but quickly transferred to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He was unhappy with the focus at both schools on Beaux-Arts architecture, and spent his free time researching emerging architects, especially Le Corbusier. After graduating, he joined the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD) and became a friend of the Bauhaus architects Walter Gropius and Marcel Breuer. In 1948, Pei was recruited by New York City real estate magnate William Zeckendorf, for whom he worked for seven years before establishing his own independent design firm I. M. Pei & Associates in 1955, which became I. M. Pei & Partners in 1966 and later in 1989 became Pei Cobb Freed & Partners. Pei retired from full-time practice in 1990. In his retirement, he worked as an architectural consultant primarily from his sons' architectural firm Pei Partnership Architects.

Pei's first major recognition came with the Mesa Laboratory at the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Colorado (designed in 1961, and completed in 1967). His new stature led to his selection as chief architect for the John F. Kennedy Library in Massachusetts. He went on to design Dallas City Hall and the East Building of the National Gallery of Art.[2] He returned to China for the first time in 1975 to design a hotel at Fragrant Hills, and designed Bank of China Tower, Hong Kong, a skyscraper in Hong Kong for the Bank of China fifteen years later. In the early 1980s, Pei was the focus of controversy when he designed a glass-and-steel pyramid for the Musée du Louvre in Paris. He later returned to the world of the arts by designing the Morton H. Meyerson Symphony Center in Dallas, the Miho Museum in Japan, Shigaraki, near Kyoto, and the chapel of the junior and high school: MIHO Institute of Aesthetics, the Suzhou Museum in Suzhou,[3] Museum of Islamic Art in Qatar, and the Grand Duke Jean Museum of Modern Art, abbreviated to Mudam, in Luxembourg.

Pei won a wide variety of prizes and awards in the field of architecture, including the AIA Gold Medal in 1979, the first Praemium Imperiale for Architecture in 1989, and the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum in 2003. In 1983, he won the Pritzker Prize, which is sometimes referred to as the Nobel Prize of architecture.

童年 Childhood

[编辑]

Pei's ancestry traces back to the Ming Dynasty, when his family moved from Anhui province to Suzhou. Finding wealth in the sale of medicinal herbs, the family stressed the importance of helping the less fortunate.[5] Ieoh Ming Pei was born on 26 April 1917 to Tsuyee and Lien Kwun, and the family moved to Hong Kong one year later. The family eventually included five children. As a boy, Pei was very close to his mother, a devout Buddhist who was recognized for her skills as a flautist. She invited him (and not his brothers or sisters) to join her on meditation retreats.[6] His relationship with his father was less intimate. Their interactions were respectful but distant.[7]

贝聿铭的祖先在明朝时自安徽移居苏州,以药材生意发家。贝聿铭的父亲是贝祖贻,母亲为庄莲君,贝家有五个孩子(似与中文资料不符)。1917年4月26日,贝聿铭生于广州。一年后,贝家移居香港。(可能需补充搬家原因及具体家境情况)孩提时,贝聿铭与母亲关系较近。庄莲君笃信佛教,擅长吹笛。在五个孩子中,她仅仅让贝聿铭同她一起禅修冥想。贝聿铭对父亲虽然恭敬有礼,但二人关系并不如他和母亲那样亲密。(https://web.archive.org/web/20091218073038/http://www.buildbook.com.cn/magazine/book/cszg/19/3.html 中文资料中的贝家先祖

联合早报([1]):贝聿铭的祖父贝理泰(字哉安,有来源写作履泰?)20岁成为苏州府学贡生,因父亲逝世而未能为官,专心经营家族产业。贝理泰曾为知县吴次竹担任钱谷师爷。清帝退位后,贝理泰参与创办了上海银行、中国旅行社,曾任中国旅行社苏州分社经理。贝理泰有五个儿子,贝聿铭的父亲贝祖贻(诒?)排行第三。贝祖贻毕业于东吴大学。贝聿铭的母亲庄氏是清朝末任国子监祭酒的女儿。贝祖贻夫妇有三个儿子和三个女儿,贝聿铭是长子。庄氏去世后,银行将贝祖贻派往欧洲,希望能让他逐渐从丧妻之痛中走出。访欧期间,贝祖贻结识了比他小19岁的蒋士英。1932年春,贝祖贻和蒋士英在巴黎举办了婚礼。

Pei's ancestors' success meant that the family lived in the upper echelons of society, but Pei said his father was "not cultivated in the ways of the arts".[8] The younger Pei, drawn more to music and other cultural forms than to his father's domain of banking, explored art on his own. "I have cultivated myself," he said later.[7]

虽然贝聿铭家境殷实,但他的父亲对艺术并没有特别的爱好。相比父亲工作的金融行业,贝聿铭小时候对音乐和其他文化活动更感兴趣。他后来说,他对艺术的爱好是自己培养起来的。

At the age of ten, Pei moved with his family to Shanghai after his father was promoted. Pei attended St. John's Middle School, run by Anglican missionaries. Academic discipline was rigorous; students were allowed only one half-day each month for leisure. Pei enjoyed playing billiards and watching Hollywood movies, especially those of Buster Keaton and Charlie Chaplin. He also learned rudimentary English skills by reading the Bible and novels by Charles Dickens.[9]

十岁时,由于父亲升职,贝聿铭一家搬到上海。他在聖公宗开办的圣约翰中学读书。学校纪律严格,学生每一个月内只有半天时间可供娱乐。贝聿铭喜欢打撞球、看好莱坞电影。他尤其喜欢巴斯特·基頓和查理·卓别林的电影。通过阅读聖經和查尔斯·狄更斯的小说,他掌握了基本的英语技能。

Shanghai's many international elements gave it the name "Paris of the East".[11] The city's global architectural flavors had a profound influence on Pei, from The Bund waterfront area to the Park Hotel, built in 1934. He was also impressed by the many gardens of Suzhou, where he spent the summers with extended family and regularly visited a nearby ancestral shrine. The Shizilin Garden, built in the 14th century by a Buddhist monk and owned by Pei's uncle Bei Runsheng, was especially influential. Its unusual rock formations, stone bridges, and waterfalls remained etched in Pei's memory for decades. He spoke later of his fondness for the garden's blending of natural and human-built structures.[4][9]

上海众多的外国元素为之赢得了“东方巴黎”的名声。由外滩到国际饭店一带上海国际化建筑风格对贝聿铭产生了深远的影响。贝聿铭是家中长孙,祖父贝理泰要他每年夏天到苏州住一段时间。1918年,贝聿铭的叔祖父贝润生(https://qd.house.ifeng.com/column/exclusive/beishi001j http://news.163.com/19/0517/06/EFC24LDC00018AOR.html 待确认,英文维基说是叔父)买下了始建于14世纪的苏州园林狮子林。当时贝聿铭常常到此游览。狮子林的假山、石桥、瀑布令他难以忘怀,他很欣赏狮子林融合自然与人工的设计。

Soon after the move to Shanghai, Pei's mother developed cancer. As a pain reliever, she was prescribed opium, and assigned the task of preparing her pipe to Pei. She died shortly after his thirteenth birthday, and he was profoundly upset.[12] The children were sent to live with extended family; their father became more consumed by his work and more physically distant. Pei said: "My father began living his own separate life pretty soon after that."[13] His father later married a woman named Aileen, who moved to New York later in her life.[14]

搬家到上海不久,贝聿铭的母亲患上了癌症。医生在处方中列入鸦片作为止痛剂,贝聿铭负责打理烟管。贝聿铭13岁生日之后不久,他的母亲离开了人世。贝聿铭深感悲痛。贝家的子女被送去与大家族一同生活。他们的父亲忙于工作,与子女们很少见面。贝聿铭的父亲后来与蒋士云结婚。蒋士云后来移居纽约。

卢爱玲、卢艾琳、陆书华?

求学与任教(直译似乎很难受) Education and formative years

[编辑]As Pei neared the end of his secondary education, he decided to study at a university. He was accepted to a number of schools, but decided to enroll at the University of Pennsylvania.[15] Pei's choice had two roots. While studying in Shanghai, he had closely examined the catalogs for various institutions of higher learning around the world. The architectural program at the University of Pennsylvania stood out to him.[16] The other major factor was Hollywood. Pei was fascinated by the representations of college life in the films of Bing Crosby, which differed tremendously from the academic atmosphere in China. "College life in the U.S. seemed to me to be mostly fun and games", he said in 2000. "Since I was too young to be serious, I wanted to be part of it ... You could get a feeling for it in Bing Crosby's movies. College life in America seemed very exciting to me. It's not real, we know that. Nevertheless, at that time it was very attractive to me. I decided that was the country for me."[17] Pei added that "Crosby's films in particular had a tremendous influence on my choosing the United States instead of England to pursue my education."[18]

临近中学毕业时,贝聿铭决定上大学继续学业。很多学校都愿意录取他,但他最终选择了宾夕法尼亚大学。这个决定主要有两方面的考虑。当他在上海读书时,他仔细地查阅了全球高等教育机构的目录。在他看来,宾夕法尼亚大学的建筑专业尤为优秀。另一个重要因素是好莱坞。贝聿铭迷恋冰·哥羅士比电影中描述的美国大学生活,这与中国学校的气氛大相径庭。在2000年,贝聿铭回忆说,那时他印象的美国大学生活主要是欢乐和游戏,年轻尚轻的他并不是一个严肃的人,他想要加入其中;尽管知道电影中的大学生活与现实不同,但他仍然受此影响选择了美国。

In 1935 Pei boarded a boat and sailed to San Francisco, then traveled by train to Philadelphia. What he found once he got to those places, however, differed vastly from his expectations. Professors at the University of Pennsylvania based their teaching in the Beaux-Arts style, rooted in the classical traditions of ancient Greece and Rome. Pei was more intrigued by modern architecture, and also felt intimidated by the high level of drafting proficiency shown by other students. He decided to abandon architecture and transferred to the engineering program at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Once he arrived, however, the dean of the architecture school commented on his eye for design and convinced Pei to return to his original major.[19]

1935年,贝聿铭乘船前往美国旧金山,随后乘火车来到费城。他的所见所闻与他的预期完全不同。宾夕法尼亚大学的教授们讲授的课程基于学院派艺术,承袭希腊、罗马古典艺术传统。贝聿铭却更喜欢现代主义建筑。此外,其他同学精湛的制图能力也挫伤了他的自信心。他决定离开建筑学,到麻省理工学院学习工程。他进入麻省理工学院后,建筑学院院长发现他很有设计眼光,劝说他回到了建筑专业。

MIT's architecture faculty was also focused on the Beaux-Arts school, and Pei found himself uninspired by the work. In the library he found three books by the Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier. Pei was inspired by the innovative designs of the new International style, characterized by simplified form and the use of glass and steel materials. Le Corbusier visited MIT in November 1935, an occasion which powerfully affected Pei: "The two days with Le Corbusier, or 'Corbu' as we used to call him, were probably the most important days in my architectural education."[20] Pei was also influenced by the work of U.S. architect Frank Lloyd Wright. In 1938 he drove to Spring Green, Wisconsin, to visit Wright's famous Taliesin building. After waiting for two hours, however, he left without meeting Wright.[21][需要解释]

麻省理工学院的建筑学教授同样专注学院派风格,贝聿铭对此不感兴趣。学图书馆里,他找到了三本瑞士籍法国建筑师勒·柯布西耶的书。新兴的国际风格建筑推崇简单的形状、使用玻璃和钢铁材料,贝聿铭深受启发。1935年11月,柯布西耶访问麻省理工学院,这件事深刻地影响了贝聿铭。他曾提到,与柯布西耶一同度过的两天很可能是他在建筑教育中最重要的时光。贝聿铭也受到美国建筑师弗蘭克·勞埃德·賴特作品的影响。1938年,他开车去威斯康辛州春綠村,拜访著名的塔里耶森。塔里耶森是賴特为自己建造的住宅和事务所。贝聿铭等候了两个小时也没有见到赖特,离开了这里。

Although he disliked the Beaux-Arts emphasis at MIT, Pei excelled in his studies. "I certainly don't regret the time at MIT", he said later. "There I learned the science and technique of building, which is just as essential to architecture."[22] Pei received his B.Arch. degree in 1940.[23]

麻省理工学院建筑学科注重学院派风格。虽然贝聿铭不喜欢学院派,但他的成绩很好。他后来回忆称,自己并不后悔在麻省理工学院的时光。他在这里学到了建筑学中至关重要科学和技术。1940年,贝聿铭获得建筑学学士学位。

While visiting New York City in the late 1930s, Pei met a Wellesley College student named Eileen Loo. They began dating and they married in the spring of 1942. She enrolled in the landscape architecture program at Harvard University, and Pei was thus introduced to members of the faculty at Harvard's Graduate School of Design (GSD). He was excited by the lively atmosphere, and joined the GSD in December 1942.[24]

1930年代末,贝聿铭访问纽约时认识了正在维斯理学院求学的卢爱玲。两人开始约会,后来在1942年春天结婚。卢爱玲毕业后进入哈佛大学学习景觀設計,贝聿铭由此认识了哈佛大学设计学院的教师们。贝聿铭喜欢哈佛设计学院的活泼气氛,他在1942年12月加入哈佛大学设计学院。

Less than a month later, Pei suspended his work at Harvard to join the National Defense Research Committee, which coordinated scientific research into U.S. weapons technology during World War II. Pei's background in architecture was seen as a considerable asset; one member of the committee told him: "If you know how to build you should also know how to destroy."[25] The fight against Germany was ending, so he focused on the Pacific War. The U.S. realized that its bombs used against the stone buildings of Europe would be ineffective against Japanese cities, mostly constructed from wood and paper; Pei was assigned to work on incendiary bombs. Pei spent two and a half years with the NDRC, but revealed few details of his work.[26]

不到一个月后,贝聿铭暂时停下他在哈佛大学的工作,加入美国国防部科研委员会。在第二次世界大战期间,国防部科研委员会协调美国武器技术的科研工作。委员会认为贝聿铭的建筑学背景很有价值。一位委员曾对他说,如果你知道怎么盖楼,那你应该也知道怎么毁楼。对德战事已经临近尾声,贝聿铭的工作主要集中于太平洋战争。日本建筑多以木材建成(纸张??)而非石材,美国意识到在欧洲战场上针对石质建筑的炸弹用于轰炸日本时不再有效。贝聿铭被安排研究燃烧弹。他在美国国防部科研委员会工作了两年半,但他很少透露他工作的细节。

In 1945 Eileen gave birth to a son, T'ing Chung; she withdrew from the landscape architecture program in order to care for him. Pei returned to Harvard in the autumn of 1945, and received a position as assistant professor of design. The GSD was developing into a hub of resistance to the Beaux-Arts orthodoxy. At the center were members of the Bauhaus, a European architectural movement that had advanced the cause of modernist design. The Nazi regime had condemned the Bauhaus school, and its leaders left Germany. Two of these, Walter Gropius and Marcel Breuer, took positions at the Harvard GSD. Their iconoclastic focus on modern architecture appealed to Pei, and he worked closely with both men.[27]长子贝定中 次子贝建中 三子贝礼中

1945年,卢爱玲生下长子贝定中。为了照顾儿子,卢爱玲退了学。这年秋天,贝聿铭返回哈佛大学工作,并被聘为设计学助理教授。那时的哈佛大学设计学院逐渐成为反抗学院派正统的中心。推动现代主义设计的欧洲建筑运动包豪斯的一些成员当时就在设计学院工作。納粹德國不容忍包豪斯存在,包豪斯的领袖因而离开德国,其中瓦爾特·格羅佩斯(中文维基现用译名并不接近德语发音)、马塞尔·布劳耶加盟了哈佛大学设计学院。他们打破传统的现代建筑主张吸引了贝聿铭,贝聿铭与两人合作紧密。

One of Pei's design projects at the GSD was a plan for an art museum in Shanghai. He wanted to create a mood of Chinese authenticity in the architecture without using traditional materials or styles.[28] The design was based on straight modernist structures, organized around a central courtyard garden, with other similar natural settings arranged nearby. It was very well received; Gropius, in fact, called it "the best thing done in [my] master class".[28] Pei received his M.Arch. degree in 1946, and taught at Harvard for another two years.[1][29]

在哈佛大学设计学院期间,贝聿铭的设计工作之一是一座位于上海的艺术博物馆(中文资料称这是贝的硕士毕业设计)。他想在不使用传统材料、样式的条件下呈现出原汁原味的中式趣味。这项设计使用的完全是现代主义的结构,整个建筑围绕中心的花园庭院展开,附近也设置了类似的天然景观。这项设计受到好评。格罗皮乌斯称赞这件作品是他的硕士班上最好的一件。1946年,贝聿铭获得建筑学硕士学位,此后又在哈佛任教两年。

建筑师生涯 Career

[编辑]1948–1956: 生涯早期,韦伯纳普公司 1948–1956: early career with Webb and Knapp

[编辑]In the spring of 1948 Pei was recruited by New York real estate magnate William Zeckendorf to join a staff of architects for his firm of Webb and Knapp to design buildings around the country. Pei found Zeckendorf's personality the opposite of his own; his new boss was known for his loud speech and gruff demeanor. Nevertheless, they became good friends and Pei found the experience personally enriching. Zeckendorf was well connected politically, and Pei enjoyed learning about the social world of New York's city planners.[30]

1948年春,纽约地产大亨威廉·泽肯多夫聘请贝聿铭加入他的韦伯纳普公司建筑团队,为美国各地设计建筑。贝聿铭发现泽肯多夫的性格与他截然相反,泽肯多夫讲话声音很大、举止粗鲁。然而,两人成了好朋友,贝聿铭感觉这段经历很充实。泽肯多夫在政界有很多熟人。了解纽约城市规划者的社交圈的过程给了贝聿铭很多乐趣。

His first project for Webb and Knapp was an apartment building with funding from the Housing Act of 1949. Pei's design was based on a circular tower with concentric rings. The areas closest to the supporting pillar handled utilities and circulation; the apartments themselves were located toward the outer edge. Zeckendorf loved the design and even showed it off to Le Corbusier when they met. The cost of such an unusual design was too high, however, and the building never moved beyond the model stage.[31]

贝聿铭为韦伯纳普公司制作的第一项设计是一座公寓建筑,建筑受1949年住宅法资助。贝聿铭的设计方案为一个圆形的高楼和数个同心的圆环。承重柱附近的空间布置了通道和管线(公共设施utilities是水、煤气、电线吗?又不能译成公用事业),公寓房间则安排在楼的外沿。泽肯多夫很喜欢这个方案,他与勒·柯布西耶见面时甚至还把这个设计拿给柯布西耶看。然而,这一非同寻常的设计所需的建设经费过于高昂,贝聿铭的设计方案仅仅停留在模型阶段。

131 Ponce de Leon Avenue, Atlanta

Pei finally saw his architecture come to life in 1949,[32] when he designed a two-story corporate building for Gulf Oil in Atlanta, Georgia. The building was demolished in February 2013 although the front facade will be retained as part of an apartment development. His use of marble for the exterior curtain wall brought praise from the journal Architectural Forum.[33] Pei's designs echoed the work of Mies van der Rohe in the beginning of his career as also shown in his own weekend-house in Katonah, New York in 1952. Soon Pei was so inundated with projects that he asked Zeckendorf for assistants, which he chose from his associates at the GSD, including Henry N. Cobb and Ulrich Franzen. They set to work on a variety of proposals, including the Roosevelt Field Shopping Mall. The team also redesigned the Webb and Knapp office building, transforming Zeckendorf's office into a circular space with teak walls and a glass clerestory. They also installed a control panel into the desk that allowed their boss to control the lighting in his office. The project took one year and exceeded its budget, but Zeckendorf was delighted with the results.[34]

1949年,贝聿铭的设计方案头一次得以付诸实施。那时,他设计了位于佐治亚州亚特兰大的海湾石油公司办公楼。这座建筑在2013年2月被拆除,但是前立面被保留了下来用于之后公寓楼的建设。这座办公楼有两层。《建筑论坛》(Architectural Forum)杂志称赞了贝聿铭在建筑外幕墙上对大理石的使用。贝聿铭早期的设计令人想到路德維希·密斯·凡德羅的作品,1952年他为自己设计的位于纽约州卡托纳的周末度假房也体现了这样的风格。不久,贝聿铭的项目多到了难以应付的程度,他向泽肯多夫请求雇佣助手。贝聿铭挑选哈佛大学设计学院同事作为助手,包括亨利·N·柯布、乌尔里希·弗兰岑。他们设计了很多项目,包括罗斯福菲尔德购物中心。贝聿铭的团队还重新设计了韦伯纳普公司的办公楼,把泽肯多夫的办公室改造成了装有柚木墙和玻璃高侧窗的圆形空间。他们还在泽肯多夫的桌上安装了一块控制面板,用来控制办公室里的照明。这项计划耗时一年,耗费的资金超出了预算,但泽肯多夫很满意改造结果。

In 1952 Pei and his team began work on a series of projects in Denver, Colorado. The first of these was the Mile High Center, which compressed the core building into less than twenty-five percent of the total site; the rest is adorned with an exhibition hall and fountain-dotted plazas.[36] One block away, Pei's team also redesigned Denver's Courthouse Square, which combined office spaces, commercial venues, and hotels. These projects helped Pei conceptualize architecture as part of the larger urban geography. "I learned the process of development," he said later, "and about the city as a living organism."[37] These lessons, he said, became essential for later projects.[37]

1952年,贝聿铭与他的团队开始为丹佛设计一系列的项目。第一个项目是一英里高中心(Mile High Center),他们把核心建筑压缩到整片区域四分之一的范围内,其余部分则用展厅、有喷泉的广场妆点着。与此相距一个街区的地方,贝聿铭的团队重新设计了丹佛的法院广场,将办公空间、商业场所和宾馆融合在一起。这些工程使得贝聿铭形成了一种观念,也就是把建筑作为城市地理的一部分。他后来说,他学到了开发土地的过程,还学到了将城市视为一个有机体。

Pei and his team also designed a united urban area for Washington, D.C., L'Enfant Plaza (named for French-American architect Pierre Charles L'Enfant).[38] Pei's associate Araldo Cossutta was the lead architect for the plaza's North Building (955 L'Enfant Plaza SW) and South Building (490 L'Enfant Plaza SW).[38] Vlastimil Koubek was the architect for the East Building (L'Enfant Plaza Hotel, located at 480 L'Enfant Plaza SW), and for the Center Building (475 L'Enfant Plaza SW; now the United States Postal Service headquarters).[38] The team set out with a broad vision that was praised by both The Washington Post and Washington Star (which rarely agreed on anything), but funding problems forced revisions and a significant reduction in scale.[39]皮埃尔·夏尔·朗方 阿拉尔多·科苏塔 弗拉斯季米尔·库贝克

贝聿铭和他的团队还为华盛顿哥伦比亚特区设计了朗方广场建筑群。广场以美籍法裔建筑师皮埃尔·夏尔·朗方命名。贝聿铭的助手阿拉尔多·科苏塔担任广场北楼(朗方广场西南955号,955 L'Enfant Plaza SW)和南楼(朗方广场西南490号,490 L'Enfant Plaza SW)的首席建筑师,弗拉斯季米尔·库贝克则担任东楼(朗方广场酒店,地址为朗方广场西南480号,480 L'Enfant Plaza SW)和中楼(后来用作美國郵政署总部,地址为朗方广场西南475号,475 L'Enfant Plaza SW)的设计师。贝聿铭团队的远见(不会真是说视野开阔吧?查下原书)得到了《华盛顿邮报》和一贯挑剔的《华盛顿明星报》的称赞。然而,由于资金问题,建筑设计不得不进行修改,建筑的规模也只好大幅缩水。

In 1955 Pei's group took a step toward institutional independence from Webb and Knapp by establishing a new firm called I. M. Pei & Associates. (The name changed later to I. M. Pei & Partners.) They gained the freedom to work with other companies, but continued working primarily with Zeckendorf. The new firm distinguished itself through the use of detailed architectural models. They took on the Kips Bay residential area on the east side of Manhattan, where Pei set up Kips Bay Towers, two large long towers of apartments with recessed windows (to provide shade and privacy) in a neat grid, adorned with rows of trees. Pei involved himself in the construction process at Kips Bay, even inspecting the bags of concrete to check for consistency of color.[40]

1955年,贝聿铭的团队成立了名叫“贝聿铭与同事们”(I. M. Pei & Associates)的公司,迈出了从韦伯纳普公司独立的一步。公司后来改名为贝聿铭与合伙人(I. M. Pei & Partners)。他们可以自由同其他公司合作,不过仍然以与泽肯多夫合作为主。他们的新公司因复杂精细的建筑模型而独树一帜。他们承担了曼哈顿东部的基普斯湾住宅区工程。在这里,贝聿铭设计了基普斯湾塔,这是两幢又大又长的公寓塔楼。外墙整齐的格子里装有凹窗,既能遮阳又能提供私密空间(凹窗译法对吗?真有这个功效吗?)。建筑区内还栽着几列树。贝聿铭亲自参与了基普斯湾的建设工程,他甚至检查一袋袋的混凝土以确保其颜色一致。

The company continued its urban focus with the Society Hill project in central Philadelphia. Pei designed the Society Hill Towers, a three-building residential block injecting cubist design into the 18th-century milieu of the neighborhood. As with previous projects, abundant green spaces were central to Pei's vision, which also added traditional townhouses to aid the transition from classical to modern design.[41]

公司继续以都市建设为中心,参与了費城中心的协会山工程(就别译社会山了)。贝聿铭设计了协会山塔。协会山塔由三座住宅楼组成,设计上将立体派风格融入到周边的18世纪建筑中。与贝聿铭之前的工程一样,协会山塔也有大量的绿地。为了让从传统设计向现代设计的过渡更为自然,他还增添了一些连排屋。

From 1958 to 1963 Pei and Ray Affleck developed a key downtown block of Montreal in a phased process that involved one of Pei's most admired structures in the Commonwealth, the cruciform tower known as the Royal Bank Plaza (Place Ville Marie). According to the Canadian Encyclopedia "its grand plaza and lower office buildings, designed by internationally famous US architect I. M. Pei, helped to set new standards for architecture in Canada in the 1960s ... The tower's smooth aluminum and glass surface and crisp unadorned geometric form demonstrate Pei's adherence to the mainstream of 20th-century modern design."[42]

1958年至1963年间,贝聿铭同拉伊·阿弗莱克在蒙特利尔市中心分阶段开发了一个重要的街区。其中包括贝聿铭在整个英联邦里最受欢迎的建筑之一皇家银行大厦(后改名为玛丽城广场)。这是一座平面为十字形的大楼。《加拿大百科全书》称,“知名美国建筑师贝聿铭设计的宏伟的广场与低处的办公建筑为1960年代的加拿大设立了建筑的新标杆……大楼光滑的铝质与玻璃质表面、清爽而无装饰的几何外形体现了贝聿铭对20世纪现代设计主流风格的尊崇”。

Although these projects were satisfying, Pei wanted to establish an independent name for himself. In 1959 he was approached by MIT to design a building for its Earth science program. The Green Building continued the grid design of Kips Bay and Society Hill. The pedestrian walkway at the ground floor, however, was prone to sudden gusts of wind, which embarrassed Pei. "Here I was from MIT," he said, "and I didn't know about wind-tunnel effects."[43] At the same time, he designed the Luce Memorial Chapel in at Tunghai University in Taichung, Taiwan. The soaring structure, commissioned by the same organisation that had run his middle school in Shanghai, broke severely from the cubist grid patterns of his urban projects.[44][45]

尽管这些工程已经令人满意,但贝聿铭还希望为自己建立独立的名声。1959年,麻省理工大学请他为学校的地球科学项目设计一幢大楼。他为麻省理工大学设立的绿楼延续了他在基普斯湾和协会山的网格设计。然而,绿楼底层的通道却易受狂风吹袭,使楼门在大风天里无法开启。(此处需补充参考资料。或许可以配图)这让贝聿铭非常尴尬。他说,“我是麻省理工大学毕业的,可我却不知道风洞效应”。最终,校方拆下了绿楼的大门,将底层空间改为开放式的景框(补充来源)。大约与此同时,他为台湾臺中市東海大學设计了路思義教堂。路思义教堂与贝聿铭少时在上海就读的圣约翰中学由同一组织开办。这座教堂高耸的结构与贝聿铭在城市建筑中的立体派网格设计大不相同。

The challenge of coordinating these projects took an artistic toll on Pei. He found himself responsible for acquiring new building contracts and supervising the plans for them. As a result, he felt disconnected from the actual creative work. "Design is something you have to put your hand to," he said. "While my people had the luxury of doing one job at a time, I had to keep track of the whole enterprise."[46] Pei's dissatisfaction reached its peak at a time when financial problems began plaguing Zeckendorf's firm. I. M. Pei and Associates officially broke from Webb and Knapp in 1960, which benefited Pei creatively but pained him personally. He had developed a close friendship with Zeckendorf, and both men were sad to part ways.[47]

协调这些工程的挑战让贝聿铭付出了艺术上的代价。他发现自己既需要想方设法为公司赢得新的建设合同,又要管理这些项目的设计。结果是,他觉得自己离开了真正创造性的工作。“设计是件必须亲手做的事情”,他说道,“当我的人可以奢侈地同时只做一件事的时候,我却得盯着整个公司”。当泽肯多夫的公司受到财务问题困扰时,贝聿铭的不满达到了顶峰。1960年,“贝聿铭与同事们”公司正式同韦伯纳普公司分家。这虽然对贝聿铭的创作有利,但是也让他感到难过。数年来,他与泽肯多夫结下了深厚的友谊。两人都因离别而伤心。

国家大气研究中心与相关工程 NCAR and related projects

[编辑]Pei was able to return to hands-on design when he was approached in 1961 by Walter Orr Roberts to design the new Mesa Laboratory for the National Center for Atmospheric Research outside Boulder, Colorado. The project differed from Pei's earlier urban work; it would rest in an open area in the foothills of the Rocky Mountains. He drove with his wife around the region, visiting assorted buildings and surveying the natural environs. He was impressed by the United States Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs, but felt it was "detached from nature".[49]

1961年,沃尔特·奥尔·罗伯茨邀请贝聿铭为国家大气研究中心设计新建梅萨实验室。项目地点位于科罗拉多州波德城外。贝聿铭得以重新亲手从事设计。这项工程与贝聿铭此前设计的都市建筑不同,梅萨实验室建在洛磯山脈脚下的开阔空间中。贝聿铭与妻子驱车在附近考查了各种各样的建筑,也调查了附近的自然环境。位于科罗拉多斯普林斯的美国空军学院建筑给他留下了深刻的印象,但是贝聿铭觉得这座建筑脱离了这里的自然环境。

The conceptualization stages were important for Pei, presenting a need and an opportunity to break from the Bauhaus tradition. He later recalled the long periods of time he spent in the area: "I recalled the places I had seen with my mother when I was a little boy—the mountaintop Buddhist retreats. There in the Colorado mountains, I tried to listen to the silence again—just as my mother had taught me. The investigation of the place became a kind of religious experience for me."[48]

对贝聿铭而言,概念设计是一个重要阶段。一方面,这个项目有必要打破包豪斯的传统,另一方面这也是突破包豪斯传统的机会。后来,他回忆起在这一带度过的漫长时光:“我想起了小时候和母亲一起去过的地方——山顶的佛教禅修所。在科罗拉多山里,我试着再次聆听静默——就像母亲以前教我的那样。于我而言,对这个地方的调查变成了一种宗教体验。”

Pei also drew inspiration from the Mesa Verde cliff dwellings of the Ancient Pueblo Peoples; he wanted the buildings to exist in harmony with their natural surroundings.[50] To this end, he called for a rock-treatment process that could color the buildings to match the nearby mountains. He also set the complex back on the mesa overlooking the city, and designed the approaching road to be long, winding, and indirect.[51]

贝聿铭也从古普埃布洛人在梅萨维德的崖居那里获得了灵感。他想让这座建筑与其自然环境和谐共生。为此,他增加了石材处理环节,让建筑物的颜色同附近的山岩相配。他将建筑群设置在山的平顶上,俯瞰着城市。通往建筑的路设计得长而迂回。

Roberts disliked Pei's initial designs, referring to them as "just a bunch of towers".[52] Roberts intended his comments as typical of scientific experimentation, rather than artistic critique; still, Pei was frustrated. His second attempt, however, fit Roberts' vision perfectly: a spaced-out series of clustered buildings, joined by lower structures and complemented by two underground levels. The complex uses many elements of cubist design, and the walkways are arranged to increase the probability of casual encounters among colleagues.[53]

Once the laboratory was built, several problems with its construction became apparent. Leaks in the roof caused difficulties for researchers, and the shifting of clay soil beneath caused cracks in the buildings which were expensive to repair. Still, both architect and project manager were pleased with the final result. Pei refers to the NCAR complex as his "breakout building", and he remained a friend of Roberts until the scientist died in March 1990.[55]

实验室刚刚完工,建设时的一些问题就暴露了出来。屋顶的漏洞给研究人员带来了麻烦。建筑下面粘土的滑动造成楼体裂缝,维修费用昂贵。然而,贝聿铭和项目经理都很满意最终的结果。贝聿铭把这一建筑群称作他的突破之作。他与罗伯茨的友谊一直延续,直到后者在1990年3月离世。

The success of NCAR brought renewed attention to Pei's design acumen. He was recruited to work on a variety of projects, including the S. I. Newhouse School of Public Communications at Syracuse University, the Everson Museum of Art in Syracuse, NY, the Sundrome terminal at John F. Kennedy International Airport in New York City, and dormitories at New College of Florida.[56]

国家大气研究中心项目取得成功,使得贝聿铭的设计才华再次引起了关注。他受聘设计了诸多建筑,包括雪城大學纽豪斯公共传播学院、纽约州锡拉丘兹(需补充字词转换)的伊弗森美术馆、纽约市約翰·甘迺迪國際機場6号航站楼、佛羅里達新學院宿舍楼等。

肯尼迪图书馆 Kennedy Library

[编辑]After President John F. Kennedy was assassinated in November 1963, his family and friends discussed how to construct a library that would serve as a fitting memorial. A committee was formed to advise Kennedy's widow Jacqueline, who would make the final decision. The group deliberated for months and considered many famous architects.[57] Eventually, Kennedy chose Pei to design the library, based on two considerations. First, she appreciated the variety of ideas he had used for earlier projects. "He didn't seem to have just one way to solve a problem," she said. "He seemed to approach each commission thinking only of it and then develop a way to make something beautiful."[58] Ultimately, however, Kennedy made her choice based on her personal connection with Pei. Calling it "really an emotional decision", she explained: "He was so full of promise, like Jack; they were born in the same year. I decided it would be fun to take a great leap with him."[59]

1963年11月,美国总统约翰·肯尼迪遇刺。为了纪念肯尼迪,他的家人朋友讨论了建设一座图书馆的方案。为此,他们成立了一个委员会,为肯尼迪遗孀杰奎琳·肯尼迪担任顾问,最终的决定权在杰奎琳手中。他们仔细考虑了好几个月,想到了很多知名建筑师。最后,杰奎琳·肯尼迪选择了贝聿铭。这有两方面的考虑。一方面,杰奎琳很欣赏贝聿铭之前作品里丰富多样的方案。杰奎琳曾说,贝聿铭解决问题并不只有一种方案,他受托设计建筑时心里只想着这一件事,然后就能想出美丽的方案(真别扭)。然而,杰奎琳选择贝聿铭的原因根本上是因为二人的私交。她把这称作一个感性的决定。她解释说,贝聿铭前途无量,就像她的丈夫一样;贝聿铭和约翰·肯尼迪恰巧出生在同一年。她说,与贝聿铭一起向前迈出一大步会很有趣。(译得真烂)

The project was plagued with problems from the outset. The first was scope. President Kennedy had begun considering the structure of his library soon after taking office, and he wanted to include archives from his administration, a museum of personal items, and a political science institute. After the assassination, the list expanded to include a fitting memorial tribute to the slain president. The variety of necessary inclusions complicated the design process and caused significant delays.[60]

这项工程一开始就遇到了困难。第一个麻烦是这座建筑要承担的功能较多。肯尼迪就任总统不久就开始设想他的图书馆的结构。他希望图书馆存放他的政府的档案,要有一个私人物品的博物馆,还要有一个政治学研究所。肯尼亚遇刺之后,图书馆的功能又加了一条:纪念遇害的肯尼迪总统。建筑囊括的内容多种多样,使得设计过程复杂起来,严重延误了进度。

Pei's first proposed design included a large glass pyramid that would fill the interior with sunlight, meant to represent the optimism and hope that Kennedy's administration had symbolized for so many in the US. Mrs. Kennedy liked the design, but resistance began in Cambridge, the first proposed site for the building, as soon as the project was announced. Many community members worried that the library would become a tourist attraction, causing particular problems with traffic congestion. Others worried that the design would clash with the architectural feel of nearby Harvard Square. By the mid-70s, Pei tried proposing a new design, but the library's opponents resisted every effort.[62] These events pained Pei, who had sent all three of his sons to Harvard, and although he rarely discussed his frustration, it was evident to his wife. "I could tell how tired he was by the way he opened the door at the end of the day," she said. "His footsteps were dragging. It was very hard for I. M. to see that so many people didn't want the building."[63]

贝聿铭最开始计划为图书馆修建一座很大的玻璃金字塔,既让太阳光照亮内部空间,又代表着乐观与希望。对很多美国人而言,肯尼迪政府正是象征着乐观和希望。肯尼迪夫人喜欢这个设计。然而,这时剑桥市民开始抵制图书馆项目。肯尼迪图书馆计划出台时,就将建设地点选在了马萨诸塞州的剑桥市。剑桥市的很多居民担心图书馆会成为一个旅游景点,由此引发交通拥堵问题。还有人担心这座建筑的设计会破坏附近哈佛广场的建筑气氛。70年代中期,贝聿铭尝试改用新的设计方案,但是反对者们毫不让步。贝聿铭的三个儿子都在哈佛大学读书。这些反对意见深深地困扰着他。尽管他很少谈及那段日子里的沮丧心情,但他的妻子却清楚地看到了他的真实心境。她说,他开门的动作充满疲惫感,步履沉重;这么多人不喜欢这座建筑,让他倍感艰难。

Finally the project moved to Columbia Point, near the University of Massachusetts Boston. The new site was less than ideal; it was located on an old landfill, and just over a large sewage pipe. Pei's architectural team added more fill to cover the pipe and developed an elaborate ventilation system to conquer the odor. A new design was unveiled, combining a large square glass-enclosed atrium with a triangular tower and a circular walkway.[64]

最终,肯尼迪图书馆的地点改到麻州大學波士頓分校附近的哥伦比亚角。这并不是一个理想的地点。图书馆的位置原先是一座垃圾填埋场,图书馆正下方有一个很粗的下水管道。贝聿铭的建筑团队做了更多的填埋,以把下水管遮起来;他们还设计了复杂的通风系统,以解决臭气问题。图书馆采用了全新的设计方案,有一个方形的中庭、三角形塔楼和环形的步道。

The John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum was dedicated on 20 October 1979. Critics generally liked the finished building, but the architect himself was unsatisfied. The years of conflict and compromise had changed the nature of the design, and Pei felt that the final result lacked its original passion. "I wanted to give something very special to the memory of President Kennedy," he said in 2000. "It could and should have been a great project."[61] Pei's work on the Kennedy project boosted his reputation as an architect of note.[65]

1979年10月20日,肯尼迪总统图书馆暨博物馆举行了落成典礼。评论家们大体上喜欢这座建筑,但是贝聿铭自己并不满意。多年的争执和妥协已经改变了设计的本质,贝聿铭觉得最终的结果完全失去了原来的激情。他在2000年时说道,他本想用特别的设计来纪念肯尼迪,图书馆本来可以成为一项伟大的工程,而且也应该成为一项伟大的工程。(可能还是该意译,或者拿掉,或者用其他资料代替?)

"Pei Plan" in Oklahoma City

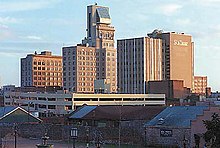

[编辑]The Pei Plan was a failed urban redevelopment initiative designed for downtown Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, in the 1960s and 1970s. It is the informal name for two related commissions by Pei – namely the Central Business District General Neighborhood Renewal Plan (design completed 1964) and the Central Business District Project I-A Development Plan (design completed 1966). It was formally adopted in 1965, and implemented in various public and private phases throughout the 1960s and 1970s.

The plan called for the demolition of hundreds of old downtown structures in favor of renewed parking, office building, and retail developments, in addition to public projects such as the Myriad Convention Center and the Myriad Botanical Gardens. It was the dominant template for downtown development in Oklahoma City from its inception through the 1970s. The plan generated mixed results and opinion, largely succeeding in re-developing office building and parking infrastructure but failing to attract its anticipated retail and residential development. Significant public resentment also developed as a result of the destruction of multiple historic structures. As a result, Oklahoma City's leadership avoided large-scale urban planning for downtown throughout the 1980s and early 1990s, until the passage of the Metropolitan Area Projects (MAPS) initiative in 1993.[66][67]

Providence's Cathedral Square

[编辑]

Another city which turned to Pei for urban renewal during this time was Providence, Rhode Island.[68] In the late 1960s, Providence hired Pei to redesign Cathedral Square, a once-bustling civic center which had become neglected and empty, as part of an ambitious larger plan to redesign downtown.[68] Pei's new plaza, modeled after the Greek Agora marketplace, opened in 1972.[68] Unfortunately, the city ran out of money before Pei's vision could be fully realized.[68] Also, recent construction of a low-income housing complex and Interstate 95 had changed the neighborhood's character permanently.[68] In 1974, The Providence Evening Bulletin called Pei's new plaza a "conspicuous failure."[68] By 2016, media reports characterized the plaza as a neglected, little-visited "hidden gem".[68]

Augusta, Georgia

[编辑]

In 1974, the city of Augusta, Georgia turned to Pei and his firm for downtown revitalization.[69] From the plan, the Chamber of Commence building and Bicentennial Park, were completed.[70] In 1976, Pei designed a distinctive modern penthouse, that was added to the roof of architect William Lee Stoddart's historic Lamar Building, designed in 1916.[71] The penthouse is a modern take on a pyramid, predating Pei's more famous Louvre Pyramid. It has been criticized by architectural critic James Howard Kunstler as an "Eyesore of the Month" with him comparing it to Darth Vader's helmet.[72] In 1980, he and his company designed the Augusta Civic Center, now known as the James Brown Arena.[73]

Dallas City Hall

[编辑]

Kennedy's assassination led indirectly to another commission for Pei's firm. In 1964 the acting mayor, Erik Jonsson, began working to change the community's image. Dallas was known and disliked as the city where the president had been killed, but Jonsson began a program designed to initiate a community renewal. One of the goals was a new city hall, which could be a "symbol of the people".[75] Jonsson, a co-founder of Texas Instruments, learned about Pei from his associate Cecil Howard Green, who had recruited the architect for MIT's Earth Sciences building.[76]

Pei's approach to the new Dallas City Hall mirrored those of other projects; he surveyed the surrounding area and worked to make the building fit. In the case of Dallas, he spent days meeting with residents of the city and was impressed by their civic pride. He also found that the skyscrapers of the downtown business district dominated the skyline, and sought to create a building which could face the tall buildings and represent the importance of the public sector. He spoke of creating "a public-private dialogue with the commercial high-rises".[77]

Working with his associate Theodore Musho, Pei developed a design centered on a building with a top much wider than the bottom; the facade leans at an angle of 34 degrees, which shades the building from the Texas sun. A plaza stretches out before the building, and a series of support columns holds it up. It was influenced by Le Corbusier's High Court building in Chandigarh, India; Pei sought to use the significant overhang to unify building and plaza. The project cost much more than initially expected, and took 11 years. Revenue was secured in part by including a subterranean parking garage. The interior of the city hall is large and spacious; windows in the ceiling above the eighth floor fill the main space with light.[78]

The city of Dallas received the building well, and a local television news crew found unanimous approval of the new city hall when it officially opened to the public in 1978. Pei himself considered the project a success, even as he worried about the arrangement of its elements. He said: "It's perhaps stronger than I would have liked; it's got more strength than finesse."[80] He felt that his relative lack of experience left him without the necessary design tools to refine his vision, but the community liked the city hall enough to invite him back. Over the years he went on to design five additional buildings in the Dallas area.[81]

波士顿汉考克大厦 Hancock Tower, Boston

[编辑]While Pei and Musho were coordinating the Dallas project, their associate Henry Cobb had taken the helm for a commission in Boston. John Hancock Insurance chairman Robert Slater hired I. M. Pei & Partners to design a building that could overshadow the Prudential Tower, erected by their rival.[82]

贝聿铭与穆绍忙于协调达拉斯的工程,而他们的同事亨利·N·柯布在波士顿受托设计一个新的项目。恒康保险公司主席罗伯特·斯莱特聘请贝聿铭与合伙人设计所建造一座新的大楼,以超越竞争对手保德信的保德信大厦。(似应译为普天寿或保德信大厦,此Prudential非彼Prudential!)

After the firm's first plan was discarded due to a need for more office space, Cobb developed a new plan around a towering parallelogram, slanted away from the Trinity Church and accented by a wedge cut into each narrow side. To minimize the visual impact, the building was covered in large reflective glass panels; Cobb said this would make the building a "background and foil" to the older structures around it.[83] When the Hancock Tower was finished in 1976, it was the tallest building in New England.[84]

公司设计的第一版方案由于办公空间不足而被抛弃。柯布设计的新方案是一座平行四边形的高楼(看卫星图似乎说的是平面呈平行四边形,待查对参考资料),沿着远离三一堂 (波士顿)波士顿三一堂的方向倾斜(莫名其妙,是说平面的平行四边形倾斜还是说立面倾斜?),大楼较窄的两个面各有一个楔形的槽。为了尽量减小视觉冲击,大楼外面覆盖着大块的反光玻璃板。柯布说,这可以让大楼成为附近老建筑的背景和陪衬。1976年,约翰·汉考克大厦建成,成为当时新英格蘭地区最高的建筑。

Serious issues of execution became evident in the tower almost immediately. Many glass panels fractured in a windstorm during construction in 1973. Some detached and fell to the ground, causing no injuries but sparking concern among Boston residents. In response, the entire tower was reglazed with smaller panels. This significantly increased the cost of the project. Hancock sued the glass manufacturers, Libbey-Owens-Ford, as well as I. M. Pei & Partners, for submitting plans that were "not good and workmanlike".[85] LOF countersued Hancock for defamation, accusing Pei's firm of poor use of their materials; I. M. Pei & Partners sued LOF in return. All three companies settled out of court in 1981.[86]

工程刚刚开始,施工上的严重问题就暴露了出来。1973年,大楼建设过程遭遇风暴,很多玻璃板破裂。有些玻璃板脱落、下坠到了地面,虽然没有造成人员伤亡,但是引发了波士顿居民的忧虑。为此,整座大楼全部改用更小的玻璃板。整个工程的造价急剧增加。恒康保险将玻璃制造商利比-欧文斯-福特、贝聿铭与合伙人设计所告上法庭。恒康保险起诉贝聿铭的公司提交“不好、技艺纯熟却无新意的方案”(不知怎么译)。利比-欧文斯-福特反告恒康保险诽谤,还起诉贝聿铭的设计所使用玻璃产品方法不当。贝聿铭与合伙人设计所也将利比-欧文斯-福特告上法庭。1981年,三家公司达成庭外和解。

The project became an albatross for Pei's firm. Pei himself refused to discuss it for many years. The pace of new commissions slowed and the firm's architects began looking overseas for opportunities. Cobb worked in Australia and Pei took on jobs in Singapore, Iran, and Kuwait. Although it was a difficult time for everyone involved, Pei later reflected with patience on the experience. "Going through this trial toughened us," he said. "It helped to cement us as partners; we did not give up on each other."[87]

汉考克大厦最终成为贝聿铭与合伙人设计所的污点。贝聿铭很多年来都不愿说起汉考克大厦工程。设计所接到的业务减少,公司的建筑师开始到海外寻找机会。柯布在澳大利亚揽活,而贝聿铭则在新加坡、伊朗、科威特做了一些设计。后来,贝聿铭回忆起这段日子里大家的忍耐力,他说,“这场磨炼使得我们更加坚韧,巩固了我们合伙人的关系,我们谁也没有抛弃谁”。(还是不想译直接引语)

National Gallery East Building, Washington, DC

[编辑]

In the mid-1960s, directors of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., declared the need for a new building. Paul Mellon, a primary benefactor of the gallery and a member of its building committee, set to work with his assistant J. Carter Brown (who became gallery director in 1969) to find an architect. The new structure would be located to the east of the original building, and tasked with two functions: offer a large space for public appreciation of various popular collections; and house office space as well as archives for scholarship and research. They likened the scope of the new facility to the Library of Alexandria. After inspecting Pei's work at the Des Moines Art Center in Iowa and the Johnson Museum at Cornell University, they offered him the commission.[89]

Pei took to the project with vigor, and set to work with two young architects he had recently recruited to the firm, William Pedersen and Yann Weymouth. Their first obstacle was the unusual shape of the building site, a trapezoid of land at the intersection of Constitution and Pennsylvania Avenues. Inspiration struck Pei in 1968, when he scrawled a rough diagram of two triangles on a scrap of paper. The larger building would be the public gallery; the smaller would house offices and archives. This triangular shape became a singular vision for the architect. As the date for groundbreaking approached, Pedersen suggested to his boss that a slightly different approach would make construction easier. Pei simply smiled and said: "No compromises."[90]

The growing popularity of art museums presented unique challenges to the architecture. Mellon and Pei both expected large crowds of people to visit the new building, and they planned accordingly. To this end, he designed a large lobby roofed with enormous skylights. Individual galleries are located along the periphery, allowing visitors to return after viewing each exhibit to the spacious main room. A large mobile sculpture by American artist Alexander Calder was later added to the lobby.[91] Pei hoped the lobby would be exciting to the public in the same way as the central room of the Guggenheim Museum in New York. The modern museum, he said later, "must pay greater attention to its educational responsibility, especially to the young".[92]

Materials for the building's exterior were chosen with careful precision. To match the look and texture of the original gallery's marble walls, builders re-opened the quarry in Knoxville, Tennessee, from which the first batch of stone had been harvested. The project even found and hired Malcolm Rice, a quarry supervisor who had overseen the original 1941 gallery project. The marble was cut into three-inch-thick blocks and arranged over the concrete foundation, with darker blocks at the bottom and lighter blocks on top.[94]

The East Building was honored on 30 May 1978, two days before its public unveiling, with a black-tie party attended by celebrities, politicians, benefactors, and artists. When the building opened, popular opinion was enthusiastic. Large crowds visited the new museum, and critics generally voiced their approval. Ada Louise Huxtable wrote in The New York Times that Pei's building was "a palatial statement of the creative accommodation of contemporary art and architecture".[93] The sharp angle of the smaller building has been a particular note of praise for the public; over the years it has become stained and worn from the hands of visitors.[95]

Some critics disliked the unusual design, however, and criticized the reliance on triangles throughout the building. Others took issue with the large main lobby, particularly its attempt to lure casual visitors. In his review for Artforum, critic Richard Hennessy described a "shocking fun-house atmosphere" and "aura of ancient Roman patronage".[93] One of the earliest and most vocal critics, however, came to appreciate the new gallery once he saw it in person. Allan Greenberg had scorned the design when it was first unveiled, but wrote later to J. Carter Brown: "I am forced to admit that you are right and I was wrong! The building is a masterpiece."[96]

北京香山饭店 Fragrant Hills, China

[编辑]After US President Richard Nixon made his famous 1972 visit to China, a wave of exchanges took place between the two countries. One of these was a delegation of the American Institute of Architects in 1974, which Pei joined. It was his first trip back to China since leaving in 1935. He was favorably received, returned the welcome with positive comments, and a series of lectures ensued. Pei noted in one lecture that since the 1950s Chinese architects had been content to imitate Western styles; he urged his audience in one lecture to search China's native traditions for inspiration.[97]

1972年美国总统理查德·尼克松访问中国后,中美两国展开了一系列的交流活动。活动之一是1974年美國建築師學會代表团访问中国,贝聿铭是成员之一。这是他在1935年离开中国之后第一次踏上故土。他受到了热烈的欢迎。(returned the welcome with positive comments 积极评价了中国的发展??)在中国,他开展了数场讲座。其中一场讲座上,贝聿铭提到,1950年代起中国建筑师只满足于模仿西方风格。另一场讲座上,他呼吁听众从中国传统中寻找设计灵感。

In 1978, Pei was asked to initiate a project for his home country. After surveying a number of different locations, Pei fell in love with a valley that had once served as an imperial garden and hunting preserve known as Fragrant Hills. The site housed a decrepit hotel; Pei was invited to tear it down and build a new one. As usual, he approached the project by carefully considering the context and purpose. Likewise, he considered modernist styles inappropriate for the setting. Thus, he said, it was necessary to find "a third way".[99]

1978年,贝聿铭受邀为中国设计一项工程。在多个地点考察之后,贝聿铭看上了北京西郊的香山。香山曾是皇家园林。香山有一座破旧的宾馆,贝聿铭受邀将其拆除、原址新建一座酒店。秉承了他的一贯做法,贝聿铭在设计前认真地考虑了工程的背景和目标。同样,他也考虑到现代主义的风格与此地格格不入。他说,有必要寻找“第三条道路”。(原文似乎欠缺条理,查一下引用资料)

After visiting his ancestral home in Suzhou, Pei created a design based on some simple but nuanced techniques he admired in traditional residential Chinese buildings. Among these were abundant gardens, integration with nature, and consideration of the relationship between enclosure and opening. Pei's design included a large central atrium covered by glass panels that functioned much like the large central space in his East Building of the National Gallery. Openings of various shapes in walls invited guests to view the natural scenery beyond. Younger Chinese who had hoped the building would exhibit some of Cubist flavor for which Pei had become known were disappointed, but the new hotel found more favour with government officials and architects.[100]

The hotel, with 325 guest rooms and a four-story central atrium, was designed to fit perfectly into its natural habitat. The trees in the area were of special concern, and particular care was taken to cut down as few as possible. He worked with an expert from Suzhou to preserve and renovate a water maze from the original hotel, one of only five in the country. Pei was also meticulous about the arrangement of items in the garden behind the hotel; he even insisted on transporting 230短噸(210公噸) of rocks from a location in southwest China to suit the natural aesthetic. An associate of Pei's said later that he never saw the architect so involved in a project.[101]

During construction, a series of mistakes collided with the nation's lack of technology to strain relations between architects and builders. Whereas 200 or so workers might have been used for a similar building in the US, the Fragrant Hill project employed over 3,000 workers. This was mostly because the construction company lacked the sophisticated machines used in other parts of the world. The problems continued for months, until Pei had an uncharacteristically emotional moment during a meeting with Chinese officials. He later explained that his actions included "shouting and pounding the table" in frustration.[102] The design staff noticed a difference in the manner of work among the crew after the meeting. As the opening neared, however, Pei found the hotel still needed work. He began scrubbing floors with his wife and ordered his children to make beds and vacuum floors. The project's difficulties took an emotional and physical strain on the Pei family.[103]

The Fragrant Hill Hotel opened on 17 October 1982 but quickly fell into disrepair. A member of Pei's staff returned for a visit several years later and confirmed the dilapidated condition of the hotel. He and Pei attributed this to the country's general unfamiliarity with deluxe buildings.[105] The Chinese architectural community at the time gave the structure little attention, as their interest at the time centered on the work of American postmodernists such as Michael Graves.[106]

Javits Convention Center, New York

[编辑]As the Fragrant Hill project neared completion, Pei began work on the Jacob K. Javits Convention Center in New York City, for which his associate James Freed served as lead designer. Hoping to create a vibrant community institution in what was then a run-down neighborhood on Manhattan's west side, Freed developed a glass-coated structure with an intricate space frame of interconnected metal rods and spheres.[107]

The convention center was plagued from the start by budget problems and construction blunders. City regulations forbid a general contractor having final authority over the project, so architects and program manager Richard Kahan had to coordinate the wide array of builders, plumbers, electricians, and other workers. The forged steel globes to be used in the space frame came to the site with hairline cracks and other defects; 12,000 were rejected. These and other problems led to media comparisons with the disastrous Hancock Tower. One New York City official blamed Kahan for the difficulties, indicating that the building's architectural flourishes were responsible for delays and financial crises.[108] The Javits Center opened on 3 April 1986, to a generally positive reception. During the inauguration ceremonies, however, neither Freed nor Pei was recognized for their role in the project.

Le Grand Louvre, Paris

[编辑]

When François Mitterrand was elected President of France in 1981, he laid out an ambitious plan for a variety of construction projects. One of these was the renovation of the Louvre Museum. Mitterrand appointed a civil servant named Émile Biasini to oversee it. After visiting museums in Europe and the United States, including the US National Gallery, he asked Pei to join the team. The architect made three secretive trips to Paris, to determine the feasibility of the project; only one museum employee knew why he was there.[110] Pei finally agreed that a reconstruction project was not only possible, but necessary for the future of the museum. He thus became the first foreign architect to work on the Louvre.[111]

The heart of the new design included not only a renovation of the Cour Napoléon in the midst of the buildings, but also a transformation of the interiors. Pei proposed a central entrance, not unlike the lobby of the National Gallery East Building, which would link the three major buildings. Below would be a complex of additional floors for research, storage, and maintenance purposes. At the center of the courtyard he designed a glass and steel pyramid, first proposed with the Kennedy Library, to serve as entrance and anteroom skylight. It was mirrored by another inverted pyramid underneath, to reflect sunlight into the room. These designs were partly an homage to the fastidious geometry of the famous French landscape architect André Le Nôtre (1613–1700).[112] Pei also found the pyramid shape best suited for stable transparency, and considered it "most compatible with the architecture of the Louvre, especially with the faceted planes of its roofs".[109]

Biasini and Mitterrand liked the plans, but the scope of the renovation displeased Louvre director André Chabaud. He resigned from his post, complaining that the project was "unfeasible" and posed "architectural risks".[113] The public also reacted harshly to the design, mostly because of the proposed pyramid.[114] One critic called it a "gigantic, ruinous gadget";[115] another charged Mitterrand with "despotism" for inflicting Paris with the "atrocity".[115] Pei estimated that 90 percent of Parisians opposed his design. "I received many angry glances in the streets of Paris," he said.[116] Some condemnations carried nationalistic overtones. One opponent wrote: "I am surprised that one would go looking for a Chinese architect in America to deal with the historic heart of the capital of France."[117]

Soon, however, Pei and his team won the support of several key cultural icons, including the conductor Pierre Boulez and Claude Pompidou, widow of former French President Georges Pompidou, after whom another controversial museum was named. In an attempt to soothe public ire, Pei took a suggestion from then-mayor of Paris Jacques Chirac and placed a full-sized cable model of the pyramid in the courtyard. During the four days of its exhibition, an estimated 60,000 people visited the site. Some critics eased their opposition after witnessing the proposed scale of the pyramid.[118]

To minimize the impact of the structure, Pei demanded a method of glass production that resulted in clear panes. The pyramid was constructed at the same time as the subterranean levels below, which caused difficulties during the building stages. As they worked, construction teams came upon an abandoned set of rooms containing 25,000 historical items; these were incorporated into the rest of the structure to add a new exhibition zone.[119] The new Louvre courtyard was opened to the public on 14 October 1988, and the Pyramid entrance was opened the following March. By this time, public opinion had softened on the new installation; a poll found a 56 percent approval rating for the pyramid, with 23 percent still opposed. The newspaper Le Figaro had vehemently criticized Pei's design, but later celebrated the tenth anniversary of its magazine supplement at the pyramid.[120] Prince Charles of Britain surveyed the new site with curiosity, and declared it "marvelous, very exciting".[121] A writer in Le Quotidien de Paris wrote: "The much-feared pyramid has become adorable."[121] The experience was exhausting for Pei, but also rewarding. "After the Louvre," he said later, "I thought no project would be too difficult."[122] The Louvre Pyramid has become Pei's most famous structure.[123]

Meyerson Symphony Center, Dallas

[编辑]The opening of the Louvre Pyramid coincided with four other projects on which Pei had been working, prompting architecture critic Paul Goldberger to declare 1989 "the year of Pei" in The New York Times.[124] It was also the year in which Pei's firm changed its name to Pei Cobb Freed & Partners, to reflect the increasing stature and prominence of his associates. At the age of seventy-two, Pei had begun thinking about retirement, but continued working long hours to see his designs come to light.[125]

One of the projects took Pei back to Dallas, Texas, to design the Morton H. Meyerson Symphony Center. The success of city's performing artists, particularly the Dallas Symphony Orchestra then being led by conductor Eduardo Mata, led to interest by city leaders in creating a modern center for musical arts that could rival the best halls in Europe. The organizing committee contacted 45 architects, but at first Pei did not respond, thinking that his work on the Dallas City Hall had left a negative impression. One of his colleagues from that project, however, insisted that he meet with the committee. He did and, although it would be his first concert hall, the committee voted unanimously to offer him the commission. As one member put it: "We were convinced that we would get the world's greatest architect putting his best foot forward."[127]

The project presented a variety of specific challenges. Because its main purpose was the presentation of live music, the hall needed a design focused on acoustics first, then public access and exterior aesthetics. To this end, a professional sound technician was hired to design the interior. He proposed a shoebox auditorium, used in the acclaimed designs of top European symphony halls such as the Amsterdam Concertgebouw and Vienna Musikverein. Pei drew inspiration for his adjustments from the designs of the German architect Johann Balthasar Neumann, especially the Basilica of the Fourteen Holy Helpers. He also sought to incorporate some of the panache of the Paris Opéra designed by Charles Garnier.[128]

Pei's design placed the rigid shoebox at an angle to the surrounding street grid, connected at the north end to a long rectangular office building, and cut through the middle with an assortment of circles and cones. The design attempted to reproduce with modern features the acoustic and visual functions of traditional elements like filigree. The project was risky: its goals were ambitious and any unforeseen acoustic flaws would be virtually impossible to remedy after the hall's completion. Pei admitted that he did not completely know how everything would come together. "I can imagine only 60 percent of the space in this building," he said during the early stages. "The rest will be as surprising to me as to everyone else."[129] As the project developed, costs rose steadily and some sponsors considered withdrawing their support. Billionaire tycoon Ross Perot made a donation of US$10 million, on the condition that it be named in honor of Morton H. Meyerson, the longtime patron of the arts in Dallas.[130]

The building opened and immediately garnered widespread praise, especially for its acoustics. After attending a week of performances in the hall, a music critic for The New York Times wrote an enthusiastic account of the experience and congratulated the architects. One of Pei's associates told him during a party before the opening that the symphony hall was "a very mature building"; he smiled and replied: "Ah, but did I have to wait this long?"[131]

香港中银大厦 Bank of China, Hong Kong

[编辑]

A new offer had arrived for Pei from the Chinese government in 1982. With an eye toward the transfer of sovereignty of Hong Kong from the British in 1997, authorities in China sought Pei's aid on a new tower for the local branch of the Bank of China. The Chinese government was preparing for a new wave of engagement with the outside world and sought a tower to represent modernity and economic strength. Given the elder Pei's history with the bank before the Communist takeover, government officials visited the 89-year-old man in New York to gain approval for his son's involvement. Pei then spoke with his father at length about the proposal. Although the architect remained pained by his experience with Fragrant Hill, he agreed to accept the commission.[132]

1982年,中国政府又一次向贝聿铭发出了邀请。(英文版此处关于1997年香港回归的表述可能不恰当,1982年中英双方尚未谈妥,恐怕还没有确定1997年主权移交一事。)政府邀请贝聿铭为中国银行香港分行建设一座新的大楼。那时中国政府正在推动对外开放,希望用一座大楼来象征现代化和经济实力。考虑到贝聿铭的父亲曾在1949年前在中国银行任职,中国政府官员前往纽约拜访了89岁的贝祖贻,请他同意让他儿子参加设计。贝聿铭随后与他的父亲讨论了这项计划(at large译作详细或者最后好像都可以,查下来源吧)。尽管此前香山饭店工程让贝聿铭很受打击,但他还是接受了这项委托。

The proposed site in Hong Kong's Central District was less than ideal; a tangle of highways lined it on three sides. The area had also been home to a headquarters for Japanese military police during World War II, and was notorious for prisoner torture. The small parcel of land made a tall tower necessary, and Pei had usually shied away from such projects; in Hong Kong especially, the skyscrapers lacked any real architectural character. Lacking inspiration and unsure of how to approach the building, Pei took a weekend vacation to the family home in Katonah, New York. There he found himself experimenting with a bundle of sticks until he happened upon a cascading sequence.[133]

中银大厦位于香港中環,这并不是一个理想的建设地点,大楼三面被公路包围。这里在第二次世界大战期间是日本宪兵的总部,关押在此的囚犯会受到酷刑,此地因而声名狼藉。这片土地面积很小,因此大楼必须建得很高,而贝聿铭此前通常避开这种工程。特别地,在当时的香港,这样的摩天大楼缺少真正的建筑特点。贝聿铭找不到灵感,不知如何处理这项设计。这时,他去了纽约卡托纳的房子度过周末假期。在那里,他用一把小棍做起了实验。偶然间,他想到了cascading sequence(?不知怎么用中文表达)

Pei felt that his design for the Bank of China Tower needed to reflect "the aspirations of the Chinese people".[134] The design that he developed for the skyscraper was not only unique in appearance, but also sound enough to pass the city's rigorous standards for wind-resistance. The building is composed of four triangular shafts rising up from a square base, supported by a visible truss structure that distributes stress to the four corners of the base. Using the reflective glass that had become something of a trademark for him, Pei organized the facade around diagonal bracing in a union of structure and form that reiterate the triangle motif established in the plan. At the top, he designed the roofs at sloping angles to match the rising aesthetic of the building. Some influential advocates of feng shui in Hong Kong and China criticized the design, and Pei and government officials responded with token adjustments.[135]

贝聿铭认为,中银大厦的设计应该反映中国人民的向往。他设计的这座摩天大楼不仅外观独树一帜,也坚固结实,满足了香港严格的防风标准。中银大厦是四座三角形的立柱组成的。四座柱立在一个方形的底座上。四座柱由外露的桁架结构支持,桁架将应力传递到底座的四个角上。中银大厦立面使用了反射玻璃,而反射玻璃近乎于贝聿铭建筑设计的标志。玻璃幕墙和交错支撑结构共同组成了中银大厦的立面,使得结构与形式融合,再次体现了三角形的构思。贝聿铭设计的斜坡屋顶的角度与大楼向上的美感协调。中国内地和香港的一些知名风水先生批评了中银大厦设计。为了应付,贝聿铭和政府官员做了一些微调。

As the tower neared completion, Pei was shocked to witness the government's massacre of unarmed civilians at the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989. He wrote an opinion piece for The New York Times titled "China Won't Ever Be the Same", in which he said that the killings "tore the heart out of a generation that carries the hope for the future of the country".[136] The massacre deeply disturbed his entire family, and he wrote that "China is besmirched."[136]

1990–2019:博物馆工程 1990–2019: museum projects

[编辑]

As the 1990s began, Pei transitioned into a role of decreased involvement with his firm. The staff had begun to shrink, and Pei wanted to dedicate himself to smaller projects allowing for more creativity. Before he made this change, however, he set to work on his last major project as active partner: the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland, Ohio. Considering his work on such bastions of high culture as the Louvre and US National Gallery, some critics were surprised by his association with what many considered a tribute to low culture. The sponsors of the hall, however, sought Pei for specifically this reason; they wanted the building to have an aura of respectability from the beginning. As in the past, Pei accepted the commission in part because of the unique challenge it presented.[138]

Using a glass wall for the entrance, similar in appearance to his Louvre pyramid, Pei coated the exterior of the main building in white metal, and placed a large cylinder on a narrow perch to serve as a performance space. The combination of off-centered wraparounds and angled walls was, Pei said, designed to provide "a sense of tumultuous youthful energy, rebelling, flailing about".[139]

The building opened in 1995, and was received with moderate praise. The New York Times called it "a fine building", but Pei was among those who felt disappointed with the results. The museum's early beginnings in New York combined with an unclear mission created a fuzzy understanding among project leaders for precisely what was needed.[137] Although the city of Cleveland benefited greatly from the new tourist attraction, Pei was unhappy with it.[137]

At the same time, Pei designed a new museum for Luxembourg, the Musée d'art moderne Grand-Duc Jean, commonly known as the Mudam. Drawing from the original shape of the Fort Thüngen walls where the museum was located, Pei planned to remove a portion of the original foundation. Public resistance to the historical loss forced a revision of his plan, however, and the project was nearly abandoned. The size of the building was halved, and it was set back from the original wall segments to preserve the foundation. Pei was disappointed with the alterations, but remained involved in the building process even during construction.[140]

In 1995, Pei was hired to design an extension to the Deutsches Historisches Museum, or German Historical Museum in Berlin. Returning to the challenge of the East Building of the US National Gallery, Pei worked to combine a modernist approach with a classical main structure. He described the glass cylinder addition as a "beacon",[141] and topped it with a glass roof to allow plentiful sunlight inside. Pei had difficulty working with German government officials on the project; their utilitarian approach clashed with his passion for aesthetics. "They thought I was nothing but trouble", he said.[142]

1995年,贝聿铭受聘为柏林的德国历史博物馆设计扩建方案。他回到了当年设计华盛顿国家美术馆东楼的挑战上,把现代主义的方法同古典风格的主楼相结合。他把新增的玻璃圆柱建筑称作“灯塔”,其上覆盖玻璃屋顶为室内提供阳光。贝聿铭与德国政府官员的相处不顺利,官员们实用主义的方式与他对美的热切追求相冲突。他曾说,“官员们觉得,我除了麻烦啥也不是”。

Pei also worked at this time on two projects for a new Japanese religious movement called Shinji Shumeikai. He was approached by the movement's spiritual leader, Kaishu Koyama, who impressed the architect with her sincerity and willingness to give him significant artistic freedom. One of the buildings was a bell tower, designed to resemble the bachi used when playing traditional instruments like the shamisen. Pei was unfamiliar with the movement's beliefs, but explored them in order to represent something meaningful in the tower. As he said: "It was a search for the sort of expression that is not at all technical."[143]

The experience was rewarding for Pei, and he agreed immediately to work with the group again. The new project was the Miho Museum, to display Koyama's collection of tea ceremony artifacts. Pei visited the site in Shiga Prefecture, and during their conversations convinced Koyama to expand her collection. She conducted a global search and acquired more than 300 items showcasing the history of the Silk Road.[145]

One major challenge was the approach to the museum. The Japanese team proposed a winding road up the mountain, not unlike the approach to the NCAR building in Colorado. Instead, Pei ordered a hole cut through a nearby mountain, connected to a major road via a bridge suspended from ninety-six steel cables and supported by a post set into the mountain. The museum itself was built into the mountain, with 80 percent of the building underground.[146]

When designing the exterior, Pei borrowed from the tradition of Japanese temples, particularly those found in nearby Kyoto. He created a concise spaceframe wrapped into French limestone and covered with a glass roof. Pei also oversaw specific decorative details, including a bench in the entrance lobby, carved from a 350-year-old keyaki tree. Because of Koyama's considerable wealth, money was rarely considered an obstacle; estimates at the time of completion put the cost of the project at US$350 million.[147]

During the first decade of the 2000s, Pei designed a variety of buildings, including the Suzhou Museum near his childhood home.[148] He also designed the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha, Qatar at the request of the Al-Thani Family. Although it was originally planned for the corniche road along Doha Bay, Pei convinced project coordinators to build a new island to provide the needed space. He then spent six months touring the region and surveying mosques in Spain, Syria, and Tunisia. He was especially impressed with the elegant simplicity of the Mosque of Ibn Tulun in Cairo.

Once again, Pei sought to combine new design elements with the classical aesthetic most appropriate for the location of the building. The sand-colored rectangular boxes rotate evenly to create a subtle movement, with small arched windows at regular intervals into the limestone exterior. Inside, galleries are arranged around a massive atrium, lit from above. The museum's coordinators were pleased with the project; its official website describes its "true splendour unveiled in the sunlight", and speaks of "the shades of colour and the interplay of shadows paying tribute to the essence of Islamic architecture".[149]

The Macao Science Center in Macau was designed by Pei Partnership Architects in association with I. M. Pei. The project to build the science center was conceived in 2001 and construction started in 2006.[150] The center was completed in 2009 and opened by the Chinese President Hu Jintao.[151] The main part of the building is a distinctive conical shape with a spiral walkway and large atrium inside, similar to the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York. Galleries lead off the walkway, mainly consisting of interactive exhibits aimed at science education. The building is in a prominent position by the sea and is now a landmark of Macau.[151]

Style and method

[编辑]Pei's style is described as thoroughly modernist, with significant cubist themes.[152] He is known for combining traditional architectural principles with progressive designs based on simple geometric patterns – circles, squares, and triangles are common elements of his work in both plan and elevation. As one critic writes: "Pei has been aptly described as combining a classical sense of form with a contemporary mastery of method."[153] In 2000, biographer Carter Wiseman called Pei "the most distinguished member of his Late-Modernist generation still in practice".[154] At the same time, Pei himself rejects simple dichotomies of architectural trends. He once said: "The talk about modernism versus post-modernism is unimportant. It's a side issue. An individual building, the style in which it is going to be designed and built, is not that important. The important thing, really, is the community. How does it affect life?"[155]

Pei's work is celebrated throughout the world of architecture. His colleague John Portman once told him: "Just once, I'd like to do something like the East Building."[156] But this originality does not always bring large financial reward; as Pei replied to the successful architect: "Just once, I'd like to make the kind of money you do."[156] His concepts, moreover, are too individualized and dependent on context to give rise to a particular school of design. Pei refers to his own "analytical approach" when explaining the lack of a "Pei School". "For me," he said, "the important distinction is between a stylistic approach to the design; and an analytical approach giving the process of due consideration to time, place, and purpose ... My analytical approach requires a full understanding of the three essential elements ... to arrive at an ideal balance among them."[157]

Awards and honors

[编辑]In the words of his biographer, Pei won "every award of any consequence in his art",[154] including the Arnold Brunner Award from the National Institute of Arts and Letters (1963), the Gold Medal for Architecture from the American Academy of Arts and Letters (1979), the AIA Gold Medal (1979), the first Praemium Imperiale for Architecture from the Japan Art Association (1989), the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum, the 1998 Edward MacDowell Medal in the Arts,[158] and the 2010 Royal Gold Medal from the Royal Institute of British Architects. In 1983 he was awarded the Pritzker Prize, sometimes called the Nobel Prize of architecture. In its citation, the jury said: "Ieoh Ming Pei has given this century some of its most beautiful interior spaces and exterior forms ... His versatility and skill in the use of materials approach the level of poetry."[159] The prize was accompanied by a US$100,000 award, which Pei used to create a scholarship for Chinese students to study architecture in the US, on the condition that they return to China to work.[160] In 1986, he was one of twelve recipients of the Medal of Liberty. In being awarded the 2003 Henry C. Turner Prize by the National Building Museum, museum board chair Carolyn Brody praised his impact on construction innovation: "His magnificent designs have challenged engineers to devise innovative structural solutions, and his exacting expectations for construction quality have encouraged contractors to achieve high standards."[161] In December 1992, Pei was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President George H. W. Bush.[162]

个人生活 Personal life

[编辑]Pei's wife of over 70 years, Eileen Loo, died on 20 June 2014.[163] Together they had three sons, T'ing Chung (1946–2003),[164] Chien Chung (b. 1946) and Li Chung (b. 1949), and a daughter, Liane (b. 1960). T'ing Chung was an urban planner and alumnus of his father's alma mater MIT and Harvard. Chieng Chung and Li Chung, who are both Harvard Graduate School of Design alumni, founded and run Pei Partnership Architects. Liane is a lawyer.[165] Pei celebrated his 100th birthday on 26 April 2017.[166]女儿贝莲

Pei died in the New York City borough of Manhattan on 16 May 2019, at the age of 102.[167]

See also

[编辑]References

[编辑]Notes

- ^ 1.0 1.1 I.M. Pei Biography 互联网档案馆的存檔,存档日期18 February 2007. – website of Pei Cobb Freed & Partners

- ^ Goldberger, Paul. I.M. Pei, Master Architect Whose Buildings Dazzled the World, Dies at 102. The New York Times. 16 May 2019 [17 May 2019].

- ^ Suzhou Museum – Suzhou. My »Travel in China« Site. [2019-03-21].

- ^ 4.0 4.1 Boehm, p. 18.

- ^ Wiseman, pp. 29–30; von Boehm, p. 17.

- ^ Wiseman, pp. 31–32; von Boehm, p. 25.

- ^ 7.0 7.1 Wiseman, p. 31.

- ^ Quoted in Wiseman, p. 31.

- ^ 9.0 9.1 Wiseman, pp. 31–33.

- ^ Boehm, p. 22.

- ^ Boehm, p. 21.

- ^ Boehm, p. 25.

- ^ Boehm, p. 26.

- ^ Gonzalez, David. "About New York; A Chinese Oasis for the Soul on Staten Island". The New York Times. 28 November 1998. Accessed on 17 January 2011.

- ^ Wiseman, pp. 33–34.

- ^ Wiseman, p. 34.

- ^ Boehm, p. 34.

- ^ Boehm, pp. 33–34.

- ^ Wiseman, p. 35.

- ^ Boehm, p. 36.

- ^ Boehm, p. 36; Wiseman, p. 36.

- ^ Boehm, p. 40.

- ^ Boehm, pp. 40–41. Pei used the term "propaganda", which he believed to be value-neutral; his advisers disapproved.

- ^ Wiseman, p. 39; Boehm, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Quoted in von Boehm, p. 42; a slightly different wording appears in Wiseman, p. 39: "If you know how to build a building, you know how to destroy it."

- ^ Boehm, p. 42.

- ^ Wiseman, pp. 41–43; Boehm, pp. 37–40.

- ^ 28.0 28.1 Quoted in Wiseman, p., 44.

- ^ Wiseman, p. 45.

- ^ Wiseman, pp. 48–49.

- ^ Wiseman, p. 51.

- ^ I. M. Pei. www.pcf-p.com.

- ^ Wiseman, p. 52.

- ^ Wiseman, pp. 53–54.

- ^ Quoted in Wiseman, p. 61.

- ^ Wiseman, pp. 57–58.

- ^ 37.0 37.1 Boehm, p. 52.

- ^ 38.0 38.1 38.2 Williams, 2005, p. 120; Moeller and Weeks, 2006, p. 59.

- ^ Wiseman, pp. 60–62.

- ^ Wiseman, pp. 62–64.

- ^ Boehm, p. 51.

- ^ The Canadian Encyclopedia online version

- ^ Quoted in Wiseman, p. 67.

- ^ Wiseman, p. 67.

- ^ Wiseman, pp. 66–68.

- ^ Quoted in Wiseman, p. 69.

- ^ Wiseman, pp. 69–71.

- ^ 48.0 48.1 Boehm, p. 60.

- ^ Boehm, p. 59.

- ^ Wiseman, pp. 75–76.

- ^ Wiseman, p. 80.

- ^ Quoted in Wiseman, p. 79.

- ^ Wiseman, pp. 73, 86, and 90; Boehm, p. 61.

- ^ Wiseman, p. 94.

- ^ Wiseman, pp. 91 and 74.

- ^ History. 2009. New College of Florida. Retrieved on 12 November 2009.

- ^ Wiseman, pp. 96–98.

- ^ Quoted in Wiseman, p. 98.

- ^ Quoted in Wiseman, p. 99.

- ^ Wiseman, pp. 95 and 100.

- ^ 61.0 61.1 Boehm, p. 56.

- ^ Wiseman, pp. 102–113.

- ^ Quoted in Wiseman, p. 113.

- ^ Wiseman, pp. 115–116.

- ^ Wiseman, p. 119.

- ^ "Pei Plan and Pei Model History". 互联网档案馆的存檔,存档日期9 November 2010. IM Pei Oklahoma City. Oklahoma Historical Society, et al. Retrieved on 15 June 2010.

- ^ "I. M. Pei's Tale of Two Cities". 互联网档案馆的存檔,存档日期8 October 2011. Documentary film. Urban Action Foundation. Online at OKCHistory.com 互联网档案馆的存檔,存档日期14 July 2011.. Retrieved on 15 June 2010.

- ^ 68.0 68.1 68.2 68.3 68.4 68.5 68.6 Kasakove, Sophie. In Downtown Providence, A Forgotten Piece Of Architectural History. Rhode Island Public Radio. 7 September 2016 [25 September 2017]. (原始内容存档于12 October 2016).

- ^ Augusta Tomorrow – I. M. Pei's Revitalization Plan. www.augustatomorrow.com.

- ^ Broad Street – Historic Augusta Incorporated. Historic Augusta Incorporated.

- ^ Historic Augusta Incorporated » 2016 — The Penthouse at the Lamar Building, 753 Broad Street. www.historicaugusta.org.

- ^ Internet Archive Wayback Machine. Choice Reviews Online. 2011-07-01, 48 (11): 48–6007–48–6007. ISSN 0009-4978. doi:10.5860/choice.48-6007.