苯丙胺:修订间差异

Liangent-bot(留言 | 贡献) |

无编辑摘要 |

||

| 第624行: | 第624行: | ||

==嚴重過量== |

==嚴重過量== |

||

| ⚫ | |||

<!-- Next domain to be translated as it concerns the critical factor in respect of dependence, called delta Fcos |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

<onlyinclude>{{#ifeq:{{{transcludesection|Overdose}}}|Overdose| |

|||

An amphetamine overdose can lead to many different symptoms, but is rarely fatal with appropriate care.<ref name="International" /><ref name="Amphetamine toxidrome">{{cite journal |vauthors=Spiller HA, Hays HL, Aleguas A | title = Overdose of drugs for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: clinical presentation, mechanisms of toxicity, and management | journal = CNS Drugs | volume = 27| issue = 7| pages = 531–543|date=June 2013 | pmid = 23757186 | doi = 10.1007/s40263-013-0084-8 |quote=Amphetamine, dextroamphetamine, and methylphenidate act as substrates for the cellular monoamine transporter, especially the dopamine transporter (DAT) and less so the norepinephrine (NET) and serotonin transporter. The mechanism of toxicity is primarily related to excessive extracellular dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin.}}</ref> The severity of overdose symptoms increases with dosage and decreases with [[drug tolerance]] to amphetamine.<ref name="Westfall" /><ref name="International" /> Tolerant individuals have been known to take as much as 5 grams of amphetamine in a day, which is roughly 100 times the maximum daily therapeutic dose.<ref name="International" /> Symptoms of a moderate and extremely large overdose are listed below; fatal amphetamine poisoning usually also involves convulsions and [[coma]].<ref name="FDA Abuse & OD" /><ref name="Westfall" /> In 2013, overdose on amphetamine, methamphetamine, and other compounds implicated in an "[[ICD-10 Chapter V: Mental and behavioural disorders#(F10–F19) Mental and behavioural disorders due to psychoactive substance use|amphetamine use disorder]]" resulted in an estimated 3,788 deaths worldwide (3,425–4,145 deaths, [[95% confidence interval|95% confidence]]).{{#tag:ref|The 95% confidence interval indicates that there is a 95% probability that the true number of deaths lies between 3,425 and 4,145.|group="note"}}<ref name=GDB2013>{{cite journal | vauthors = Collaborators | title = Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013 | journal = Lancet | volume = 385 | issue = 9963 | pages = 117–171 | year = 2015 | pmid = 25530442 | pmc = 4340604 | doi = 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2 | url = http://www.thelancet.com/cms/attachment/2023546115/2043770889/mmc1.pdf | accessdate = 3 March 2015 | quote = Amphetamine use disorders ... 3,788 (3,425–4,145) }}</ref> |

|||

Pathological overactivation of the [[mesolimbic pathway]], a [[dopamine pathway]] that connects the [[ventral tegmental area]] to the [[nucleus accumbens]], plays a central role in amphetamine addiction.<ref name="Amphetamine KEGG – ΔFosB">{{cite web | title=Amphetamine – Homo sapiens (human) | url=http://www.genome.jp/kegg-bin/show_pathway?hsa05031 | work=KEGG Pathway | accessdate=31 October 2014 | author=Kanehisa Laboratories | date=10 October 2014}}</ref><ref name="Magnesium" /> Individuals who frequently overdose on amphetamine during recreational use have a high risk of developing an amphetamine addiction, since repeated overdoses gradually increase the level of [[accumbal]] [[ΔFosB]], a "molecular switch" and "master control protein" for addiction.<ref name="What the ΔFosB?" /><ref name="Cellular basis" /><ref name="Nestler_1">{{cite journal |vauthors=Robison AJ, Nestler EJ | title = Transcriptional and epigenetic mechanisms of addiction | journal = Nat. Rev. Neurosci. | volume = 12 | issue = 11 | pages = 623–637 | date = November 2011 | pmid = 21989194 | pmc = 3272277 | doi = 10.1038/nrn3111 | quote = ΔFosB serves as one of the master control proteins governing this structural plasticity.}}</ref> Once nucleus accumbens ΔFosB is sufficiently overexpressed, it begins to increase the severity of addictive behavior (i.e., compulsive drug-seeking) with further increases in its expression.<ref name="What the ΔFosB?">{{cite journal | author = Ruffle JK | title = Molecular neurobiology of addiction: what's all the (Δ)FosB about? | journal = Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse | volume = 40 | issue = 6 | pages = 428–437 | date = November 2014 | pmid = 25083822 | doi = 10.3109/00952990.2014.933840 | quote = ΔFosB is an essential transcription factor implicated in the molecular and behavioral pathways of addiction following repeated drug exposure. }}</ref><ref name="Natural and drug addictions" /> While there are currently no effective drugs for treating amphetamine addiction, regularly engaging in sustained aerobic exercise appears to reduce the risk of developing such an addiction.<ref name="Running vs addiction" /><ref name="Exercise, addiction prevention, and ΔFosB">{{cite journal | vauthors = Zhou Y, Zhao M, Zhou C, Li R | title = Sex differences in drug addiction and response to exercise intervention: From human to animal studies | journal = Front. Neuroendocrinol. | date = July 2015 | pmid = 26182835 | doi = 10.1016/j.yfrne.2015.07.001 | volume=40 | pages=24–41 | quote = Collectively, these findings demonstrate that exercise may serve as a substitute or competition for drug abuse by changing ΔFosB or cFos immunoreactivity in the reward system to protect against later or previous drug use. ... The postulate that exercise serves as an ideal intervention for drug addiction has been widely recognized and used in human and animal rehabilitation.}}</ref> Sustained aerobic exercise on a regular basis also appears to be an effective treatment for amphetamine addiction;<ref name="Exercise therapy" group="sources" /> exercise therapy improves [[wikt:clinical|clinical]] treatment outcomes and may be used as a [[combination therapy]] with [[cognitive behavioral therapy]], which is currently the best clinical treatment available.<ref name="Running vs addiction" /><ref name="Exercise Rev 3" /><ref name="Nestler CBT"/> |

|||

{{Amphetamine overdose}} --> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

==交互作用== |

==交互作用== |

||

2017年4月22日 (六) 20:41的版本

| 此條目目前正依照en:amphetamine上的内容进行翻译。 (2017年4月3日) |

| 此條目可参照英語維基百科相應條目来扩充,此條目在對應語言版為高品質條目。 |

安非他命(英文名稱:Amphetamine[note 1]为一种中樞神經興奮劑,用來治療注意力不足過動症、嗜睡症、和肥胖症。“Amphetamine”一名擷取自 alpha‑methylphenethylamine。

安非他命於西元1887年被發現,以兩種對映異構體的形式存在[note 2] ,分別是左旋安非他命和右旋安非他命。

正確來說,安非他命指的是特定的化學物質-外消旋純胺類型態[24][25],這個物質等同於安非他命的的兩個對映異構體:左旋安非他命和右旋安非他命的等比化合物之純胺類型態。 然而,實際上安非他命一詞已被廣泛的用來表示任何由安非他命對映異構體構成的物質或安非他命對映異構體本身。[21][26][25]

歸類為中樞神經興奮劑的藥物:派醋甲酯(methylphenidate)和安非他命(amphetamine)。適度適量地使用它們能提升一個人整體的衝動控制能力(inhibitory control)。[27][28] 同理,中樞神經抑制劑(depressants)(例如:酒精)由於會讓腦中神經傳導物質濃度降低、減少許多大腦區域的活性等,所以可能會造成專注力、神智清醒度等自我管理能力的下降。[29]

在醫療用的劑量範圍內,安非他命能帶來情緒以及執行功能的變化,例如:欣快感、性欲的改變、清醒度的提升、大腦執行功能的進化。安非他命所改變的生理反應包含:減少反應時間、降低疲勞、以及肌耐力的增強。然而,若攝取劑量超越醫療用的劑量範圍過多,將會導致大腦執行功能的受損以及橫紋肌溶解症。 攝取過份超越醫療用劑量範圍的安非他命將產生嚴重的藥物成癮風險。然而長期攝取醫療劑量範圍的安非他命並不會產生上癮的風險。

服用嚴重超出醫療用劑量範圍的安非他命會引起精神疾病(例如:妄想[參 1]、偏執[參 2])。然而長期攝取醫療劑量範圍的安非他命並不會引起上述疾病。

娛樂用劑量遠超過醫療用劑量範圍且伴隨著非常嚴重甚至致命的副作用。 [sources 1]

安非他命可以也曾經被用來治療鼻塞(nasal congestion)和抑鬱。

安非他命也被用來提升表現、和促進大腦的認知功能及在助興時(非醫療用途情況下)被作為增強性慾[a]、和欣快感促進劑。

安非他命在許多國家為合法的處方藥[參 3]。然而,私自散布和囤積安非他命被視為非法行為,因為安非他命被用於非醫療用途的助興可能性極高。[sources 2]

首個藥用安非他命的藥品名稱為Benzedrine。當今藥用安非他命[參 4]以下列幾種形式存在:外消旋安非他命[參 5]、Adderall[note 3]。 、dextroamphetamine、或對人體無藥效的前驅藥物體[參 6]:lisdexamfetamine。

安非他命藉著自身作用於兒茶酚胺神經傳導元素:正腎上腺素及多巴胺的特點來活化trace amine receptor ,進而增加单胺类神经递质和神经递质(excitatory neurotransmitter)在腦內的活動。[sources 3]

安非他命屬於替代性苯乙胺類的物質。由安非他命衍伸出的物質被歸納在取代苯乙胺[參 7]的分類中[note 4],比如說:安非他酮[參 8]、 cathinone、 MDMA、 和 甲基苯丙胺[參 9]。安非他命也與人體內可自然生成的兩個屬於痕量胺的神經傳導物質--特別是 phenethylamine 和 N-Methylphenethylamine--有關。 Phenethylamine 是安非他命的原始化合物,而N-methylphenethylamine則是安非他命的位置異構體(只有在甲基族中才會區分出此位置異構體)。[sources 4]

醫療用途

安非他命是用來治療注意力不足過動症(ADHD)、嗜睡症(一種睡眠疾病)、和肥胖症。有時候安非他命會以仿單標示外使用的方式處方來治療頑固性憂鬱症及頑固性強迫症[1][10] [44] [51]。 在動物試驗中,已知非常高劑量的安非他命會造成某些動物的多巴胺系統和神經系統的受損。[52][53] 但是,在人體試驗中,注意力不足過動症患者在接受安非他命的治療後,則發現安非他命可促進大腦的發育及神經的成長。[54][55][56]

回顧許多核磁共振照影(MRI)的研究後發現,長期以安非他命治療注意力不足過動症患者能顯著降低患者大腦結構及大腦執行功能上的異常。並且優化大腦中數個部位,例如:基底神經節的右尾狀核。 [54][55][56]

眾多臨床研究的系統性及統合性回顧已確立長期使用安非他命治療注意力不足過動症的療效及安全。[57][58][59]

持續長達兩年的隨機對照試驗[參 10][b]結果顯示:長期使用安非他命治療注意力不足過動症,是有效且安全的。[57][59]

兩個系統性/統合性回顧的結果顯示長期且持續地使用中樞神經興奮劑治療注意力不足過動症能有效地減少注意力不足過動症的核心症狀(核心症狀即為:過動、衝動和分心/無法專心)、增進生活品質、提升學業成就、廣泛地強化大腦的執行功能。[note 5] 這些執行功能分別與下列項目有關:學業、反社會行為、駕駛習慣、藥物濫用、肥胖、職業、日常活動、自尊心、服務使用(例如:學習、職業、健康、財金、和法律等)、社交功能。[58][59]

一篇系統性/統合性回顧標誌了一個重要發現:一個為期九個月的隨機雙盲試驗中,持續以安非他命治療的ADHD患者,其智力商數平均增加4.5單位[註 1],且在專注力、衝動、過動的改善皆呈現持續進步的態勢。[57] 另一篇系統性/統合性回顧則指出:根據迄今為止為時最長的數個臨床追蹤研究[參 11],可以得到一個結論:即便從兒童時期開始以中樞神經興奮劑治療直到老年,中樞神經興奮劑都能持續有效地控制ADHD的症狀並且減少物質濫用的風險。[59] 研究表明,ADHD與大腦的執行功能受損有關。而這些受損的執行功能分別與大腦中部分的神經傳導系統有關[參 12]。[60] ;又此部分受損的神經傳導系統和中腦皮質激素-多巴胺[參 13]的傳導及藍斑核[參 14]和前額葉[參 15]中的正腎上腺素[參 16]的傳導相關。[60]

中樞神經興奮劑,例如:methylphenidate和安非他命對於治療ADHD都是有效的,因為中樞神經興奮劑刺激了上述神經系統中的神經傳導物質活動。[30][60] [61]

至少超過80%的ADHD患者在使用中樞神經興奮劑治療後,其ADHD的症狀可以獲得改善。[62]

使用中樞神經興奮劑治療的ADHD患者相較之下,普遍與同儕及家庭成員的關係較佳並且在學校擁有較好的表現。興奮劑能使ADHD患者較不易分心、衝動、且擁有較長的專注力時間和範圍。[63] [64]

根據考科藍協作組織[參 17]所提供的文獻回顧結果[note 6]指出:使用中樞神經興奮劑治療的ADHD患者即便其症狀改善,相較於使用非中樞神經興奮劑,仍因副作用而有較高的停藥率。[66] [67]

回顧結果也發現,中樞神經興奮劑並不會惡化抽動綜合症的症狀,例如:妥瑞氏症,除非服用dextroamphetamine[c]的劑量過高才有可能在部分妥瑞氏症合併注意路不足過動症患者身上觀察到抽動綜合症的症狀惡化。[68]

中樞神經興奮劑只要依照醫師指示用藥,都是相當安全的。[69][70][70][71] 中樞神經興奮劑,例如:利他能與專思達,可能導致:心悸、頭痛、胃痛、喪失食慾、失眠、因相對專注而變得冷淡(面無表情)等副作用,因此6歲以下的兒童不適宜服用。(副作用產生與否因人而異) [72]

隨著時間推進與各方的努力,中樞神經興奮劑的相關副作用已可藉由包括但不限於劑量調整、服藥時間、飯前飯後服用、服藥頻率等服藥模式之改變以及改變藥物組合等方式獲得相當程度的減少。[73] [74] [75] [70] [76]

醫療上的禁忌

根據International Programme on Chemical Safety (IPCS)和美國食品藥物管理局 (USFDA), [note 7]

安非他命不建議處方給有藥物濫用、心血管疾病、對於各種刺激嚴重反應過度、和嚴重焦慮歷史的人。 [note 8][78][79]

安非他命也不被建議處方給正經歷動脈血管硬化(血管硬化)、中度到重度高血壓、青光眼(眼壓過高)、或甲狀腺機能亢進(身體在體內製造出過量的甲狀腺 賀爾蒙/激素)的人。 [78][79][80]

曾對中樞神經刺激劑有藥物過敏的人以及正在服用單胺氧化酶抑制劑 (MAOI)或單胺氧化酶抑制劑類藥物 (MAOIs),可能不適合使用安非他命。即便曾有合併使用安非他命和單胺氧化酶抑制劑後仍一切平安的案例。 [78][79] [81][82] IPCS和美國食品藥物管理局也同意患有神經性厭食症(anorexia nervosa)、雙極性情感疾患(bipolar disorder)、憂鬱、高血壓、mania、思覺失調症、Raynaud's phenomenon、心臟病發(seizures)、抽動綜合症(tics)、妥瑞氏症(Tourette's disease)、和有甲狀腺問題、肝腎問題的人在使用安非他命時應密切追蹤上述疾病的變化。 [78][79]

人體試驗證明,醫療用劑量下的安非他命並不會導致胎兒或新生兒畸形(i.e., it is not a human teratogen)。然而超越醫療用劑量甚多的安非他命確實會增加胎兒或新生兒畸形的機會。 [79]

研究觀察發現,安非他命會進入母親的母乳中,因此不建議授乳中的母親避免在授乳期間使用安非他命。 [78][79]

由於安非他命可能影響食慾繼而導致可反轉的身高及體重的成長遲緩, [note 9] ,因此建議兒童或青少年在用藥期間定期測量自己的身高及體重。 [78]

副作用

生理

心理

嚴重過量

成癮

依賴和戒斷症狀

交互作用

藥學(Pharmacology)

作用

認知方面(Cognitive)

西元2015年中,一篇系統性回顧[參 18]和一篇元分析/整合分析[參 19]回顧了數篇優秀的臨床試驗[參 20]報告後發現, 低劑量(醫療用劑量)的安非他命能適度但不強烈地促進一個人的認知功能,包含工作記憶(working memory)、長期的情節記憶(episodic memory)、衝動控制以及在一些方面的注意力(attention)。 [27] [28] 安非他命強化認知功能的效果已知是部分透過間接活化在大腦前額葉(prefrontal cortex)的dopamine receptor D1 和adrenoceptor α2。 [30] [27] 一篇2014年的系統性回顧發現低劑量(醫療用劑量)的安非他命能促進memory consolidation,進而提升一個人的recall of information。 [84] 低劑量(醫療用劑量)的安非他命也可增加大腦皮層(質)區的效率,這能讓一個人的工作記憶(working memory)獲得進步。 [30] [85] 安非他命和其他用於治療ADHD的中樞神經刺激劑能透過提升task saliency來增加一個人去做事情的動機、並強化一個人的警覺心(清醒度),因而能刺激一個人開始做「以目標為導向」的行為。 [30] [86] [87] 中樞神經興奮劑(例如:安非他命)能提升一個人在困難且枯燥的任務中的表現。 [30] [87] [88] 超過醫療用劑量範圍(包含其誤差範圍及容許最大上限)的安非他命劑量將不利於工作記憶(working memory)和其他的認知功能。 [30][87]

生理(physical)

雖然安非他命可以提升速度、耐力(延遲疲勞的發生)、肌耐力、身體素質和警覺心並減少心理反應時間。[31][35] [31] [89] [90] 然而,「非因醫療需求使用安非他命」在各種運動場合都是被嚴格禁止的。[91] [92]

安非他命藉由抑制多巴胺在中樞神經系統中的回收及外流來促進耐力和反應時間的提升。 [89][90] [93] 安非他命和其他作用於多巴胺系統的藥物一樣,都能增加在固定施力(levels of perceived exertion)下的動力(能)輸出。這是因為安非他命能奪取(override)體溫的「安全開關」的控制權並將身體核心溫度(core temperature limit)的上限提高以取得在體溫安全上限提高前被身體保留的能量。 [90] [94] [95] 於醫療用劑量範圍(包含其誤差範圍),安非他命的副作用不至於影響運動員的運動表現; [31][89] 然而,當攝取的劑量過多時,安非他命可能會引起嚴重的後果,例如:橫紋肌溶解症和體溫過高。 [32][34] [89]

藥效動力學(Pharmacodynamics)

藥物代謝動力學(Pharmacokinetics)

安非他命的口服生體可利用率[參 21]與腸胃的pH值連動; [96] 安非他命非常容易在腸道被吸收,dextroampetamine的生體可利用率在多數的情況下高於75%。 [2] 安非他命呈弱鹼性,其pKa值介於9–10之間;[4] 因此,當pH值呈鹼性時,多數的安非他命會以其易溶於脂類的free base形式存在。在此情況下,身體會通過腸道上表皮富含脂類的細胞膜[參 22]來吸收安非他命。 [4] [96] 相反地,酸性的pH值表示安非他命主要以易溶於水的離子[參 23](鹽)形式存在,因此較少能被吸收。 [4] 大約15–40%循環於血管中的安非他命與血漿蛋白[參 24]相連接。 [3] 安非他命的對映異構物的半衰期會隨著尿液的pH值而有所不同。 [4] 當尿液的酸鹼值落在正常範圍中,dextroamphetamine和levoamphetamine的半衰期分別為9–11 小時及 11–14 小時。 [4] 酸性飲食會導致安非他命的對映異構物的半衰期降低至8–11 小時;鹼性飲食則會使安非他命的對映異構物的半衰期增加到16–31 小時。 [5][11]

成分為安非他命或其衍生物的短效藥品大約在口服後三小時在體內達到最高血漿濃度;而成分為安非他命或其衍生物的長效藥品則在口服後大約七小時在體內達到最高血漿濃度。 [4]

安非他命主要透過腎臟來代謝,大約30–40%的藥物以藥物本身原始的型態從酸鹼度正常的尿液中排出。 [4] 當尿液是鹼性時,安非他命傾向以其free base型態存在,因此較少被排泄。 [4]

當尿液的pH值失常時,各種安非他命的分解物在尿液中重新結合的程度將從最低1%到最高75%。該程度的高低大多取決於於尿液的酸鹼值,尿液越酸,結合率越高;尿液愈鹼,結合率越低。 [4] 安非他命通常於口服後兩天內自體內完全代謝完畢。 [5] 安非他命確切的半衰期及藥效作用期隨著(小於兩天的)重複服用導致的血漿內安非他命濃度(plasma concentration of amphetamine)的增加而延長。[97]

對人體無藥效的前驅藥物體(prodrug):lisdexamfetamine並不若安非他命一樣容易受腸胃道環境的pH值影響; [98] lisdexamfetamine在腸道被吸收進入血管的血液後很快就會透過水解(hydrolysis)的方式轉化為dextroamphetamine。而參與這水解反應的酶(enzymes)與紅血球有關。 [98]

Lisdexamfetamine的半衰期通常小於一個小時。 [98]

細胞色素 P450 2D6(Cytochrome P450 2D6、或CYP2D6)、多巴胺β羥化酶(Dopamine β-hydroxylase、或DBH)、flavin-containing monooxygenase 3、butyrate-CoA ligase、和 glycine N-acyltransferase為已知在人體中參與[註 2]「安非他命」及「安非他命代謝後之產物」的代謝反應的酶(enzyme)。 [sources 5]

「安非他命代謝後之產物」包含:4-hydroxyamphetamine、4-hydroxynorephedrine、4-hydroxyphenylacetone、苯甲酸(benzoic acid)、馬尿酸(hippuric acid)、苯丙醇胺(norephedrine)、苯基丙酮(phenylacetone)[註 3] [4] [5] [6]。

在這些「安非他命代謝後之產物」之中,有實際藥效的產物(sympathomimetics)為:4‑hydroxyamphetamine[101]、4‑hydroxynorephedrine[102]、和norephedrine[103]。

安非他命的主要代謝途徑包含:aromatic para-hydroxylation、aliphatic alpha- 、beta-hydroxylation、N-oxidation、N-dealkylation、和 deamination。 [4][5]

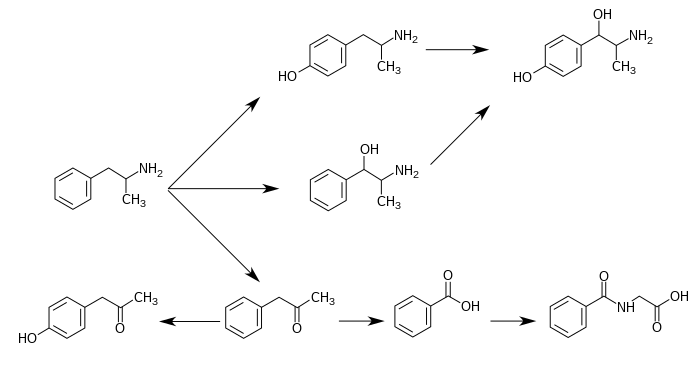

下圖為已知的「安非他命」代謝途徑和「安非他命代謝後之產物」: [4][16][6]

苯丙胺的代謝途徑

從酸鹼度正常的尿液中可發現,大約30–40%的「安非他命」以本身原始的型態排出;大約50%的安非他命以不具藥效的「安非他命代謝後之產物」(即為圖片中最下列的產物)的型態排出。 [4] 剩下的10–20%則為「安非他命代謝後之產物」之中,有實際藥效的產物。 [4] 苯甲酸(Benzoic acid)被butyrate-CoA連接酶(butyrate-CoA ligase)代謝後成為一個中介物質/中間產物(intermediate product):benzoyl-CoA [99] 隨後透過glycine N-acyltransferase代謝並轉化為馬尿酸(hippuric acid)。[100] |

相關的內部生成化合物/混和物(endogenous compound)

歷史、社會與文化

合法狀態與條件

藥品

備註A

- ^ 别名有:1-phenylpropan-2-amine (IUPAC name), α-methylbenzeneethanamine, α-methylphenethylamine, amfetamine (International Nonproprietary Name [INN]), β-phenylisopropylamine, desoxynorephedrine, and speed.[18][21][22]

- ^ 對映異構體指的是 are molecules that are mirror images of one another; they are structurally identical, but of the opposite orientation.[23]Levoamphetamine and dextroamphetamine are also known as L-amph or levamfetamine (INN) and D-amph or dexamfetamine (INN) respectively.[18]

- ^ "Adderall" is a 品牌名稱 as opposed to a nonproprietary name; because the latter ("dextroamphetamine sulfate, dextroamphetamine saccharate, amphetamine sulfate, and amphetamine aspartate" [45]) is excessively long, this article exclusively refers to this amphetamine mixture by the brand name.

- ^ The term "amphetamines" also refers to a chemical class, but, unlike the class of substituted amphetamines,[13] the "amphetamines" class does not have a standardized definition in academic literature.[25] One of the more restrictive definitions of this class includes only the racemate and enantiomers of amphetamine and methamphetamine.[25] The most general definition of the class encompasses a broad range of pharmacologically and structurally related compounds.[25]

Due to confusion that may arise from use of the plural form, this article will only use the terms "amphetamine" and "amphetamines" to refer to racemic amphetamine, levoamphetamine, and dextroamphetamine and reserve the term "substituted amphetamines" for its structural class. - ^ The ADHD-related outcome domains with the greatest proportion of significantly improved outcomes from long-term continuous stimulant therapy include academics (~55% of academic outcomes improved), driving (100% of driving outcomes improved), non-medical drug use (47% of addiction-related outcomes improved), obesity (~65% of obesity-related outcomes improved), self esteem (50% of self-esteem outcomes improved), and social function (67% of social function outcomes improved).[58]

The largest effect sizes for outcome improvements from long-term stimulant therapy occur in the domains involving academics (e.g., grade point average, achievement test scores, length of education, and education level), self-esteem (e.g., self-esteem questionnaire assessments, number of suicide attempts, and suicide rates), and social function (e.g., peer nomination scores, social skills, and quality of peer, family, and romantic relationships).[58]

Long-term combination therapy for ADHD (i.e., treatment with both a stimulant and behavioral therapy) produces even larger effect sizes for outcome improvements and improves a larger proportion of outcomes across each domain compared to long-term stimulant therapy alone.[58] - ^ Cochrane Collaboration reviews are high quality meta-analytic systematic reviews of randomized controlled trials.[65]

- ^ 美國食品藥物管理局核准的藥品使用指引及醫療上的禁忌(放在藥盒中的仿單/說明書)並非為了限制醫師的決策而是為了避免藥商恣意宣稱藥物的作用。醫師可以此為參考,並依照每位病人的實際情況做出獨立的判斷。 [77]

- ^ 然而根據一篇回顧性論文,安非他命可以處方給曾有藥物濫用歷史的人,不過需要有對患者適度的藥品控管,例如:每天由醫護人員配給處方劑量。[1]

- ^ 曾受此副作用的用藥者,身高及體重在在短暫停藥後恢復至應有水準是可以被預期的。[57][59][83] 根據追蹤,持續三年過程不停歇的安非他命治療(沒有合併任何積極減少安非他命副作用的療法的情況下)平均會減少 2公分的最終身高。 [83]

備註B

- ^ 智力測驗結果與專注力有關,詳見注意力不足過動症#智力

- ^ 酶做為反應的催化劑catalyst,並不實際參與反應。

- ^ 不是苯丙酮

注释

英文名稱對照

- ^ 英文名稱為:delusions

- ^ 英文名稱為:paranoia

- ^ 英文名稱為:Prescription drug

- ^ 英文名稱為:Pharmaceutical amphetamine

- ^ 英文名稱為:racemic amphetamine

- ^ 英文名稱為:Prodrug

- ^ 英文名稱為:substituted amphetamine

- ^ 英文名稱為:Bupropion

- ^ 英文名稱為:meth-amphetamine

- ^ 英文名稱為:Randomized controlled trials

- ^ 英文名稱為:follow-up studies

- ^ 英文名稱為:neurotransmitter systems

- ^ 英文名稱為:dopamine

- ^ 英文名稱為:locus coeruleus

- ^ 英文名稱為:prefrontal cortex

- ^ 英文名稱為:nor-epinephrine或nor-adrenaline

- ^ 英文名稱為:Cochrane Collaboration

- ^ 英文名稱為:systematic review

- ^ 英文名稱為:meta-analysis

- ^ 英文名稱為:臨床試驗

- ^ 英文名稱為:bioavailability

- ^ 英文名稱為:cell membrane

- ^ 英文名稱為:cation

- ^ 英文名稱為:plasma protein

引用

來源

- ^ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 引用错误:没有为名为

Amph Uses的参考文献提供内容 - ^ 2.0 2.1 Dextroamphetamine. DrugBank. University of Alberta. 8 February 2013.

|section-url=被忽略 (帮助);|section=被忽略 (帮助); - ^ 3.0 3.1

Amphetamine. DrugBank. University of Alberta. 8 February 2013.

|section-url=被忽略 (帮助);|section=被忽略 (帮助); - ^ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 4.14 4.15 4.16 4.17 4.18 4.19 Adderall XR Prescribing Information (PDF). United States Food and Drug Administration. Shire US Inc: 12–13. December 2013 [30 December 2013].

- ^ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4

Amphetamine. Pubchem Compound. National Center for Biotechnology Information.

|section-url=被忽略 (帮助);|section=被忽略 (帮助); - ^ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Santagati NA, Ferrara G, Marrazzo A, Ronsisvalle G. Simultaneous determination of amphetamine and one of its metabolites by HPLC with electrochemical detection. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. September 2002, 30 (2): 247–255. PMID 12191709. doi:10.1016/S0731-7085(02)00330-8.

- ^ amphetamine/dextroamphetamine. Medscape. WebMD.

Onset of action: 30–60 min

|section-url=被忽略 (帮助);|section=被忽略 (帮助); - ^ 8.0 8.1 8.2

Millichap JG. Chapter 9: Medications for ADHD. Millichap JG (编). Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Handbook: A Physician's Guide to ADHD 2nd. New York, USA: Springer. 2010: 112. ISBN 9781441913968.

Table 9.2 Dextroamphetamine formulations of stimulant medication

Dexedrine [Peak:2–3 h] [Duration:5–6 h] ...

Adderall [Peak:2–3 h] [Duration:5–7 h]

Dexedrine spansules [Peak:7–8 h] [Duration:12 h] ...

Adderall XR [Peak:7–8 h] [Duration:12 h]

Vyvanse [Peak:3–4 h] [Duration:12 h] - ^ 9.0 9.1 Brams M, Mao AR, Doyle RL. Onset of efficacy of long-acting psychostimulants in pediatric attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Postgrad. Med. September 2008, 120 (3): 69–88. PMID 18824827. doi:10.3810/pgm.2008.09.1909.

- ^ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 Adderall IR Prescribing Information (PDF). United States Food and Drug Administration. Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc.: 1–6. October 2015 [18 May 2016].

- ^ 11.0 11.1

AMPHETAMINE. United States National Library of Medicine – Toxnet. Hazardous Substances Data Bank.

Concentrations of (14)C-amphetamine declined less rapidly in the plasma of human subjects maintained on an alkaline diet (urinary pH > 7.5) than those on an acid diet (urinary pH < 6). Plasma half-lives of amphetamine ranged between 16-31 hr & 8-11 hr, respectively, & the excretion of (14)C in 24 hr urine was 45 & 70%.

|section-url=被忽略 (帮助);|section=被忽略 (帮助); - ^ 12.0 12.1

Mignot EJ. A practical guide to the therapy of narcolepsy and hypersomnia syndromes. Neurotherapeutics. October 2012, 9 (4): 739–752. PMC 3480574

. PMID 23065655. doi:10.1007/s13311-012-0150-9.

. PMID 23065655. doi:10.1007/s13311-012-0150-9.

- ^ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3

Glennon RA. Phenylisopropylamine stimulants: amphetamine-related agents. Lemke TL, Williams DA, Roche VF, Zito W (编). Foye's principles of medicinal chemistry 7th. Philadelphia, USA: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2013: 646–648 [11 September 2015]. ISBN 9781609133450.

The phase 1 metabolism of amphetamine analogs is catalyzed by two systems: cytochrome P450 and flavin monooxygenase. ... Amphetamine can also undergo aromatic hydroxylation to p-hydroxyamphetamine. ... Subsequent oxidation at the benzylic position by DA β-hydroxylase affords p-hydroxynorephedrine. Alternatively, direct oxidation of amphetamine by DA β-hydroxylase can afford norephedrine.

- ^ 14.0 14.1

Taylor KB. Dopamine-beta-hydroxylase. Stereochemical course of the reaction (PDF). J. Biol. Chem. January 1974, 249 (2): 454–458 [6 November 2014]. PMID 4809526.

Dopamine-β-hydroxylase catalyzed the removal of the pro-R hydrogen atom and the production of 1-norephedrine, (2S,1R)-2-amino-1-hydroxyl-1-phenylpropane, from d-amphetamine.

- ^ 15.0 15.1

Horwitz D, Alexander RW, Lovenberg W, Keiser HR. Human serum dopamine-β-hydroxylase. Relationship to hypertension and sympathetic activity. Circ. Res. May 1973, 32 (5): 594–599. PMID 4713201. doi:10.1161/01.RES.32.5.594.

Subjects with exceptionally low levels of serum dopamine-β-hydroxylase activity showed normal cardiovascular function and normal β-hydroxylation of an administered synthetic substrate, hydroxyamphetamine.

- ^ 16.0 16.1 16.2

Krueger SK, Williams DE. Mammalian flavin-containing monooxygenases: structure/function, genetic polymorphisms and role in drug metabolism. Pharmacol. Ther. June 2005, 106 (3): 357–387. PMC 1828602

. PMID 15922018. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.01.001.

. PMID 15922018. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.01.001.

"Table 5: N-containing drugs and xenobiotics oxygenated by FMO" - ^ 17.0 17.1 Cashman JR, Xiong YN, Xu L, Janowsky A. N-oxygenation of amphetamine and methamphetamine by the human flavin-containing monooxygenase (form 3): role in bioactivation and detoxication. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. March 1999, 288 (3): 1251–1260. PMID 10027866.

- ^ 18.0 18.1 18.2 引用错误:没有为名为

PubChem Header的参考文献提供内容 - ^ 引用错误:没有为名为

Properties的参考文献提供内容 - ^ Amphetamine. Chemspider.

|section-url=被忽略 (帮助);|section=被忽略 (帮助); - ^ 21.0 21.1 引用错误:没有为名为

DrugBank1的参考文献提供内容 - ^ 引用错误:没有为名为

Acute amph toxicity的参考文献提供内容 - ^ Enantiomer. IUPAC Goldbook. International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry. [14 March 2014]. doi:10.1351/goldbook.E02069. (原始内容存档于17 March 2013).

One of a pair of molecular entities which are mirror images of each other and non-superposable.

- ^ 24.0 24.1

Guidelines on the Use of International Nonproprietary Names (INNS) for Pharmaceutical Substances. World Health Organization. 1997 [1 December 2014].

In principle, INNs are selected only for the active part of the molecule which is usually the base, acid or alcohol. In some cases, however, the active molecules need to be expanded for various reasons, such as formulation purposes, bioavailability or absorption rate. In 1975 the experts designated for the selection of INN decided to adopt a new policy for naming such molecules. In future, names for different salts or esters of the same active substance should differ only with regard to the inactive moiety of the molecule. ... The latter are called modified INNs (INNMs).

- ^ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 25.4 25.5

Yoshida T. Chapter 1: Use and Misuse of Amphetamines: An International Overview. Klee H (编). Amphetamine Misuse: International Perspectives on Current Trends. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Harwood Academic Publishers. 1997: 2 [1 December 2014]. ISBN 9789057020810.

Amphetamine, in the singular form, properly applies to the racemate of 2-amino-1-phenylpropane. ... In its broadest context, however, the term [amphetamines] can even embrace a large number of structurally and pharmacologically related substances.

- ^ 26.0 26.1 Amphetamine. Medical Subject Headings. United States National Library of Medicine. [16 December 2013].

- ^ 27.0 27.1 27.2 Spencer RC, Devilbiss DM, Berridge CW. The Cognition-Enhancing Effects of Psychostimulants Involve Direct Action in the Prefrontal Cortex. Biol. Psychiatry. June 2015, 77 (11): 940–950. PMID 25499957. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.09.013.

The procognitive actions of psychostimulants are only associated with low doses. Surprisingly, despite nearly 80 years of clinical use, the neurobiology of the procognitive actions of psychostimulants has only recently been systematically investigated. Findings from this research unambiguously demonstrate that the cognition-enhancing effects of psychostimulants involve the preferential elevation of catecholamines in the PFC and the subsequent activation of norepinephrine α2 and dopamine D1 receptors. ... This differential modulation of PFC-dependent processes across dose appears to be associated with the differential involvement of noradrenergic α2 versus α1 receptors. Collectively, this evidence indicates that at low, clinically relevant doses, psychostimulants are devoid of the behavioral and neurochemical actions that define this class of drugs and instead act largely as cognitive enhancers (improving PFC-dependent function). This information has potentially important clinical implications as well as relevance for public health policy regarding the widespread clinical use of psychostimulants and for the development of novel pharmacologic treatments for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and other conditions associated with PFC dysregulation. ... In particular, in both animals and humans, lower doses maximally improve performance in tests of working memory and response inhibition, whereas maximal suppression of overt behavior and facilitation of attentional processes occurs at higher doses.

引用错误:带有name属性“Unambiguous PFC D1 A2”的<ref>标签用不同内容定义了多次 - ^ 28.0 28.1 Ilieva IP, Hook CJ, Farah MJ. Prescription Stimulants' Effects on Healthy Inhibitory Control, Working Memory, and Episodic Memory: A Meta-analysis. J. Cogn. Neurosci. January 2015: 1–21. PMID 25591060. doi:10.1162/jocn_a_00776.

Specifically, in a set of experiments limited to high-quality designs, we found significant enhancement of several cognitive abilities. ... The results of this meta-analysis ... do confirm the reality of cognitive enhancing effects for normal healthy adults in general, while also indicating that these effects are modest in size.

引用错误:带有name属性“Cognitive and motivational effects”的<ref>标签用不同内容定义了多次 - ^ Long-term & Short-term effects, depressants, brand names: Foundation for a drug free work.

- ^ 30.0 30.1 30.2 30.3 30.4 30.5 30.6 30.7 30.8

Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE. Chapter 13: Higher Cognitive Function and Behavioral Control. Sydor A, Brown RY (编). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience 2nd. New York, USA: McGraw-Hill Medical. 2009: 318, 321. ISBN 9780071481274.

Therapeutic (relatively low) doses of psychostimulants, such as methylphenidate and amphetamine, improve performance on working memory tasks both in normal subjects and those with ADHD. ... stimulants act not only on working memory function, but also on general levels of arousal and, within the nucleus accumbens, improve the saliency of tasks. Thus, stimulants improve performance on effortful but tedious tasks ... through indirect stimulation of dopamine and norepinephrine receptors. ...

Beyond these general permissive effects, dopamine (acting via D1 receptors) and norepinephrine (acting at several receptors) can, at optimal levels, enhance working memory and aspects of attention. - ^ 31.0 31.1 31.2 31.3 31.4

Liddle DG, Connor DJ. Nutritional supplements and ergogenic AIDS. Prim. Care. June 2013, 40 (2): 487–505. PMID 23668655. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2013.02.009.

Amphetamines and caffeine are stimulants that increase alertness, improve focus, decrease reaction time, and delay fatigue, allowing for an increased intensity and duration of training ...

Physiologic and performance effects

· Amphetamines increase dopamine/norepinephrine release and inhibit their reuptake, leading to central nervous system (CNS) stimulation

· Amphetamines seem to enhance athletic performance in anaerobic conditions 39 40

· Improved reaction time

· Increased muscle strength and delayed muscle fatigue

· Increased acceleration

· Increased alertness and attention to task - ^ 32.0 32.1 32.2 引用错误:没有为名为

FDA Abuse & OD的参考文献提供内容 - ^ 33.0 33.1 引用错误:没有为名为

Libido的参考文献提供内容 - ^ 34.0 34.1 引用错误:没有为名为

FDA Effects的参考文献提供内容 - ^ 35.0 35.1 引用错误:没有为名为

Westfall的参考文献提供内容 - ^ 引用错误:没有为名为

Cochrane的参考文献提供内容 - ^ 引用错误:没有为名为

Stimulant Misuse的参考文献提供内容 - ^ 引用错误:没有为名为

NHM-Addiction doses的参考文献提供内容 - ^ 引用错误:没有为名为

Addiction risk的参考文献提供内容 - ^ 引用错误:没有为名为

EncycOfPsychopharm的参考文献提供内容 - ^ 41.0 41.1 引用错误:没有为名为

Benzedrine的参考文献提供内容 - ^ 引用错误:没有为名为

UN Convention的参考文献提供内容 - ^ 引用错误:没有为名为

Nonmedical的参考文献提供内容 - ^ 44.0 44.1 44.2 引用错误:没有为名为

Evekeo的参考文献提供内容 - ^ National Drug Code Amphetamine Search Results. National Drug Code Directory. United States Food and Drug Administration. [16 December 2013]. (原始内容存档于16 December 2013).

- ^ 引用错误:没有为名为

Miller的参考文献提供内容 - ^ 引用错误:没有为名为

Miller+Grandy 2016的参考文献提供内容 - ^ 引用错误:没有为名为

Trace Amines的参考文献提供内容 - ^ Amphetamine. European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. [19 October 2013].

- ^ 引用错误:没有为名为

Amphetamine - a substituted amphetamine的参考文献提供内容 - ^ Obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD). NHS Choice. 2016-09-28 [2017-04-04].

- ^ 引用错误:没有为名为

pmid22392347的参考文献提供内容 - ^ Berman S, O'Neill J, Fears S, Bartzokis G, London ED. Abuse of amphetamines and structural abnormalities in the brain. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. October 2008, 1141: 195–220. PMC 2769923

. PMID 18991959. doi:10.1196/annals.1441.031.

. PMID 18991959. doi:10.1196/annals.1441.031.

- ^ 54.0 54.1 Hart H, Radua J, Nakao T, Mataix-Cols D, Rubia K. Meta-analysis of functional magnetic resonance imaging studies of inhibition and attention in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: exploring task-specific, stimulant medication, and age effects. JAMA Psychiatry. February 2013, 70 (2): 185–198. PMID 23247506. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.277.

- ^ 55.0 55.1

Spencer TJ, Brown A, Seidman LJ, Valera EM, Makris N, Lomedico A, Faraone SV, Biederman J. Effect of psychostimulants on brain structure and function in ADHD: a qualitative literature review of magnetic resonance imaging-based neuroimaging studies. J. Clin. Psychiatry. September 2013, 74 (9): 902–917. PMC 3801446

. PMID 24107764. doi:10.4088/JCP.12r08287.

. PMID 24107764. doi:10.4088/JCP.12r08287.

- ^ 56.0 56.1

Frodl T, Skokauskas N. Meta-analysis of structural MRI studies in children and adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder indicates treatment effects.. Acta psychiatrica Scand. February 2012, 125 (2): 114–126. PMID 22118249. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2011.01786.x.

Basal ganglia regions like the right globus pallidus, the right putamen, and the nucleus caudatus are structurally affected in children with ADHD. These changes and alterations in limbic regions like ACC and amygdala are more pronounced in non-treated populations and seem to diminish over time from child to adulthood. Treatment seems to have positive effects on brain structure.

- ^ 57.0 57.1 57.2 57.3

Millichap JG. Chapter 9: Medications for ADHD. Millichap JG (编). Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Handbook: A Physician's Guide to ADHD 2nd. New York, USA: Springer. 2010: 121–123, 125–127. ISBN 9781441913968.

Ongoing research has provided answers to many of the parents’ concerns, and has confirmed the effectiveness and safety of the long-term use of medication.

- ^ 58.0 58.1 58.2 58.3 58.4 Arnold LE, Hodgkins P, Caci H, Kahle J, Young S. Effect of treatment modality on long-term outcomes in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a systematic review. PLoS ONE. February 2015, 10 (2): e0116407. PMC 4340791

. PMID 25714373. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0116407.

. PMID 25714373. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0116407. The highest proportion of improved outcomes was reported with combination treatment (83% of outcomes). Among significantly improved outcomes, the largest effect sizes were found for combination treatment. The greatest improvements were associated with academic, self-esteem, or social function outcomes.

Figure 3: Treatment benefit by treatment type and outcome group - ^ 59.0 59.1 59.2 59.3 59.4 Huang YS, Tsai MH. Long-term outcomes with medications for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: current status of knowledge. CNS Drugs. July 2011, 25 (7): 539–554. PMID 21699268. doi:10.2165/11589380-000000000-00000.

Recent studies have demonstrated that stimulants, along with the non-stimulants atomoxetine and extended-release guanfacine, are continuously effective for more than 2-year treatment periods with few and tolerable adverse effects. The effectiveness of long-term therapy includes not only the core symptoms of ADHD, but also improved quality of life and academic achievements. The most concerning short-term adverse effects of stimulants, such as elevated blood pressure and heart rate, waned in long-term follow-up studies. ... In the longest follow-up study (of more than 10 years), lifetime stimulant treatment for ADHD was effective and protective against the development of adverse psychiatric disorders.

- ^ 60.0 60.1 60.2 Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE. Chapter 6: Widely Projecting Systems: Monoamines, Acetylcholine, and Orexin. Sydor A, Brown RY (编). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience 2nd. New York, USA: McGraw-Hill Medical. 2009: 154–157. ISBN 9780071481274.

- ^ Bidwell LC, McClernon FJ, Kollins SH. Cognitive enhancers for the treatment of ADHD. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. August 2011, 99 (2): 262–274. PMC 3353150

. PMID 21596055. doi:10.1016/j.pbb.2011.05.002.

. PMID 21596055. doi:10.1016/j.pbb.2011.05.002.

- ^

Parker J, Wales G, Chalhoub N, Harpin V. The long-term outcomes of interventions for the management of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. (systematic review (secondary source)). September 2013, 6: 87–99. PMC 3785407

. PMID 24082796. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S49114.

. PMID 24082796. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S49114. Only one paper53 examining outcomes beyond 36 months met the review criteria. ... There is high level evidence suggesting that pharmacological treatment can have a major beneficial effect on the core symptoms of ADHD (hyperactivity, inattention, and impulsivity) in approximately 80% of cases compared with placebo controls, in the short term.

- ^ Millichap JG. Chapter 9: Medications for ADHD. Millichap JG (编). Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Handbook: A Physician's Guide to ADHD 2nd. New York, USA: Springer. 2010: 111–113. ISBN 9781441913968.

- ^ Stimulants for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. WebMD. Healthwise. 12 April 2010 [12 November 2013].

- ^ Scholten RJ, Clarke M, Hetherington J. The Cochrane Collaboration. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. August 2005,. 59 Suppl 1: S147–S149; discussion S195–S196. PMID 16052183. doi:10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602188.

- ^ Castells X, Ramos-Quiroga JA, Bosch R, Nogueira M, Casas M. Castells X , 编. Amphetamines for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. June 2011, (6): CD007813. PMID 21678370. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007813.pub2.

- ^ Punja S, Shamseer L, Hartling L, Urichuk L, Vandermeer B, Nikles J, Vohra S. Amphetamines for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. February 2016, 2: CD009996. PMID 26844979. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009996.pub2.

- ^ Pringsheim T, Steeves T. Pringsheim T , 编. Pharmacological treatment for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in children with comorbid tic disorders. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. April 2011, (4): CD007990. PMID 21491404. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007990.pub2.

- ^ 引用错误:没有为名为

medlineplus1的参考文献提供内容 - ^ 70.0 70.1 70.2 Abuse, National Institute on Drug. Stimulant ADHD Medications: Methylphenidate and Amphetamines.

- ^ Choices, N. H. S. What is a controlled medicine (drug)? - Health questions - NHS Choices. 2016-12-12.

- ^ Methylphenidate. Home of MedlinePlus → Drugs, Herbs and Supplements → Methylphenidate Methylphenidate pronounced as (meth il fen' i date). 2016-02-15 [February twenty seventh, 2017].

- ^ Combining medications could offer better results for ADHD patients. Science News. Elsevier. 2016-08-01 [January 2017]. (原始内容存档于August 2016).

"Three studies to be published in the August 2016 issue of the Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (JAACAP) report that combining two standard medications could lead to greater clinical improvements for children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) than either ADHD therapy alone.", August, 2016

- ^ Adults with ADHD. MedlinePlus the Magazine 9. 8600 Rockville Pike • Bethesda, MD 20894, United States of America: NATIONAL LIBRARY OF MEDICINE at the NATIONAL INSTITUTES OF HEALTH. Spring 2014: 19. ISSN 1937-4712 (美国英语).

- ^ Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Home → Medical Encyclopedia → Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. NATIONAL LIBRARY OF MEDICINE at the NATIONAL INSTITUTES OF HEALTH. 2016-05-25 [February twenty seventh, 2017.].

- ^ All Disorders. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. [February twenty seventh, 2017].

- ^

Kessler S. Drug therapy in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. South. Med. J. January 1996, 89 (1): 33–38. PMID 8545689. doi:10.1097/00007611-199601000-00005.

statements on package inserts are not intended to limit medical practice. Rather they are intended to limit claims by pharmaceutical companies. ... the FDA asserts explicitly, and the courts have upheld that clinical decisions are to be made by physicians and patients in individual situations.

- ^ 78.0 78.1 78.2 78.3 78.4 78.5 引用错误:没有为名为

FDA Contra Warnings的参考文献提供内容 - ^ 79.0 79.1 79.2 79.3 79.4 79.5 Heedes G, Ailakis J. Amphetamine (PIM 934). INCHEM. International Programme on Chemical Safety. [24 June 2014].

- ^ 引用错误:没有为名为

Dexedrine FDA的参考文献提供内容 - ^

Feinberg SS. Combining stimulants with monoamine oxidase inhibitors: a review of uses and one possible additional indication. J. Clin. Psychiatry. November 2004, 65 (11): 1520–1524. \ PMID 15554766 \ 请检查

|pmid=值 (帮助). doi:10.4088/jcp.v65n1113. - ^ Stewart JW, Deliyannides DA, McGrath PJ. How treatable is refractory depression?. J. Affect. Disord. June 2014, 167: 148–152. PMID 24972362. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2014.05.047.

- ^ 83.0 83.1 引用错误:没有为名为

pmid18295156的参考文献提供内容 - ^

Bagot KS, Kaminer Y. Efficacy of stimulants for cognitive enhancement in non-attention deficit hyperactivity disorder youth: a systematic review. Addiction. April 2014, 109 (4): 547–557. PMC 4471173

. PMID 24749160. doi:10.1111/add.12460.

. PMID 24749160. doi:10.1111/add.12460. Amphetamine has been shown to improve consolidation of information (0.02 ≥ P ≤ 0.05), leading to improved recall.

- ^ Devous MD, Trivedi MH, Rush AJ. Regional cerebral blood flow response to oral amphetamine challenge in healthy volunteers. J. Nucl. Med. April 2001, 42 (4): 535–542. PMID 11337538.

- ^

Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE. Chapter 10: Neural and Neuroendocrine Control of the Internal Milieu. Sydor A, Brown RY (编). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience 2nd. New York, USA: McGraw-Hill Medical. 2009: 266. ISBN 9780071481274.

Dopamine acts in the nucleus accumbens to attach motivational significance to stimuli associated with reward.

- ^ 87.0 87.1 87.2 Wood S, Sage JR, Shuman T, Anagnostaras SG. Psychostimulants and cognition: a continuum of behavioral and cognitive activation. Pharmacol. Rev. January 2014, 66 (1): 193–221. PMID 24344115. doi:10.1124/pr.112.007054.

- ^ Twohey M. Pills become an addictive study aid. JS Online. 26 March 2006 [2 December 2007]. (原始内容存档于15 August 2007).

- ^ 89.0 89.1 89.2 89.3

Parr JW. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and the athlete: new advances and understanding. Clin. Sports Med. July 2011, 30 (3): 591–610. PMID 21658550. doi:10.1016/j.csm.2011.03.007.

In 1980, Chandler and Blair47 showed significant increases in knee extension strength, acceleration, anaerobic capacity, time to exhaustion during exercise, pre-exercise and maximum heart rates, and time to exhaustion during maximal oxygen consumption (VO2 max) testing after administration of 15 mg of dextroamphetamine versus placebo. Most of the information to answer this question has been obtained in the past decade through studies of fatigue rather than an attempt to systematically investigate the effect of ADHD drugs on exercise.

- ^ 90.0 90.1 90.2

Roelands B, de Koning J, Foster C, Hettinga F, Meeusen R. Neurophysiological determinants of theoretical concepts and mechanisms involved in pacing. Sports Med. May 2013, 43 (5): 301–311. PMID 23456493. doi:10.1007/s40279-013-0030-4.

In high-ambient temperatures, dopaminergic manipulations clearly improve performance. The distribution of the power output reveals that after dopamine reuptake inhibition, subjects are able to maintain a higher power output compared with placebo. ... Dopaminergic drugs appear to override a safety switch and allow athletes to use a reserve capacity that is ‘off-limits’ in a normal (placebo) situation.

- ^ Bracken NM. National Study of Substance Use Trends Among NCAA College Student-Athletes (PDF). NCAA Publications. National Collegiate Athletic Association. January 2012 [8 October 2013].

- ^

Docherty JR. Pharmacology of stimulants prohibited by the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA). Br. J. Pharmacol. June 2008, 154 (3): 606–622. PMC 2439527

. PMID 18500382. doi:10.1038/bjp.2008.124.

. PMID 18500382. doi:10.1038/bjp.2008.124.

- ^

Parker KL, Lamichhane D, Caetano MS, Narayanan NS. Executive dysfunction in Parkinson's disease and timing deficits. Front. Integr. Neurosci. October 2013, 7: 75. PMC 3813949

. PMID 24198770. doi:10.3389/fnint.2013.00075.

. PMID 24198770. doi:10.3389/fnint.2013.00075. Manipulations of dopaminergic signaling profoundly influence interval timing, leading to the hypothesis that dopamine influences internal pacemaker, or “clock,” activity. For instance, amphetamine, which increases concentrations of dopamine at the synaptic cleft advances the start of responding during interval timing, whereas antagonists of D2 type dopamine receptors typically slow timing;... Depletion of dopamine in healthy volunteers impairs timing, while amphetamine releases synaptic dopamine and speeds up timing.

- ^

Rattray B, Argus C, Martin K, Northey J, Driller M. Is it time to turn our attention toward central mechanisms for post-exertional recovery strategies and performance?. Front. Physiol. March 2015, 6: 79. PMC 4362407

. PMID 25852568. doi:10.3389/fphys.2015.00079.

. PMID 25852568. doi:10.3389/fphys.2015.00079. Aside from accounting for the reduced performance of mentally fatigued participants, this model rationalizes the reduced RPE and hence improved cycling time trial performance of athletes using a glucose mouthwash (Chambers et al., 2009) and the greater power output during a RPE matched cycling time trial following amphetamine ingestion (Swart, 2009). ... Dopamine stimulating drugs are known to enhance aspects of exercise performance (Roelands et al., 2008)

- ^

Roelands B, De Pauw K, Meeusen R. Neurophysiological effects of exercise in the heat. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports. June 2015,. 25 Suppl 1: 65–78. PMID 25943657. doi:10.1111/sms.12350.

This indicates that subjects did not feel they were producing more power and consequently more heat. The authors concluded that the “safety switch” or the mechanisms existing in the body to prevent harmful effects are overridden by the drug administration (Roelands et al., 2008b). Taken together, these data indicate strong ergogenic effects of an increased DA concentration in the brain, without any change in the perception of effort.

- ^ 96.0 96.1 引用错误:没有为名为

FDA Interactions的参考文献提供内容 - ^ Richard RA. Chapter 5—Medical Aspects of Stimulant Use Disorders. National Center for Biotechnology Information Bookshelf. Treatment Improvement Protocol 33. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. 1999.

|section-url=被忽略 (帮助);|section=被忽略 (帮助) - ^ 98.0 98.1 98.2 Vyvanse Prescribing Information (PDF). United States Food and Drug Administration. Shire US Inc: 12–16. January 2015 [24 February 2015].

- ^ 99.0 99.1 butyrate-CoA ligase. BRENDA. Technische Universität Braunschweig.

|section-url=被忽略 (帮助);|section=被忽略 (帮助); - ^ 100.0 100.1

glycine N-acyltransferase. BRENDA. Technische Universität Braunschweig.

|section-url=被忽略 (帮助);|section=被忽略 (帮助); - ^ 引用错误:没有为名为

sympathomimetics的参考文献提供内容 - ^ 引用错误:没有为名为

metabolites的参考文献提供内容 - ^ 引用错误:没有为名为

norephedrine的参考文献提供内容

參見

外部連結

- CID 3007 from PubChem – Amphetamine

- CID 5826 from PubChem – Dextroamphetamine

- CID 32893 from PubChem – Levoamphetamine

- Comparative Toxicogenomics Database entry: Amphetamine

- Comparative Toxicogenomics Database entry: CARTPT

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||