正算子值测度:修订间差异

Mbjpxncp7k(留言 | 贡献) 通过翻译页面“POVM”创建 |

Mbjpxncp7k(留言 | 贡献) 小 →测量后的状态: 粘贴待翻译内容 |

||

| 第101行: | 第101行: | ||

它在 <math>M_{i_0}</math> 和 <math>M_{i_1}</math> 不正交时可以是不为零的。在投影测量中,这些算子必然是正交的,因此测量始终是可重复的。 |

它在 <math>M_{i_0}</math> 和 <math>M_{i_1}</math> 不正交时可以是不为零的。在投影测量中,这些算子必然是正交的,因此测量始终是可重复的。 |

||

== An example: unambiguous quantum state discrimination == |

|||

对抗机器翻译检查器 |

|||

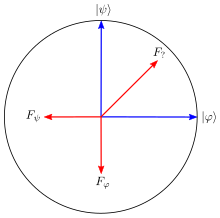

[[Image:Bloch sphere representation of optimal POVM and states for unambiguous quantum state discrimination.svg|thumb|right|[[Bloch sphere]] representation of states (in blue) and optimal POVM (in red) for unambiguous quantum state discrimination on the states <math>|\psi\rangle=|0\rangle</math> and <math>|\varphi\rangle=\frac1{\sqrt2}(|0\rangle+|1\rangle)</math>. Note that on the Bloch sphere orthogonal states are antiparallel.]] |

|||

Suppose you have a quantum system with a 2-dimensional Hilbert space that you know is in either the state <math>|\psi\rangle</math> or the state <math>|\varphi\rangle</math>, and you want to determine which one it is. If <math>|\psi\rangle</math> and <math>|\varphi\rangle</math> are orthogonal, this task is easy: the set <math>\{|\psi\rangle\langle\psi|,|\varphi\rangle\langle\varphi|\}</math> will form a PVM, and a projective measurement in this basis will determine the state with certainty. If, however, <math>|\psi\rangle</math> and <math>|\varphi\rangle</math> are not orthogonal, this task is ''impossible'', in the sense that there is no measurement, either PVM or POVM, that will distinguish them with certainty.<ref name="mike_ike"/>{{rp|87}} The impossibility of perfectly discriminating between non-orthogonal states is the basis for [[quantum information]] protocols such as [[quantum cryptography]], [[quantum coin flipping]], and [[quantum money]]. |

|||

对抗机器翻译检查器 |

|||

The task of unambiguous [[quantum state discrimination]] (UQSD) is the next best thing: to never make a mistake about whether the state is <math>|\psi\rangle</math> or <math>|\varphi\rangle</math>, at the cost of sometimes having an inconclusive result. It is possible to do this with projective measurements.<ref name="bergou"/> For example, if you measure the PVM <math>\{|\psi\rangle\langle\psi|,|\psi^\perp\rangle\langle\psi^\perp|\}</math>, where <math>|\psi^\perp\rangle</math> is the quantum state orthogonal to <math>|\psi\rangle</math>, and obtain result <math>|\psi^\perp\rangle\langle\psi^\perp|</math>, then you know with certainty that the state was <math>|\varphi\rangle</math>. If the result was <math>|\psi\rangle\langle\psi|</math>, then it is inconclusive. The analogous reasoning holds for the PVM <math>\{|\varphi\rangle\langle\varphi|,|\varphi^\perp\rangle\langle\varphi^\perp|\}</math>, where <math>|\varphi^\perp\rangle</math> is the state orthogonal to <math>|\varphi\rangle</math>. |

|||

对抗机器翻译检查器 |

|||

This is unsatisfactory, though, as you can't detect both <math>|\psi\rangle</math> and <math>|\varphi\rangle</math> with a single measurement, and the probability of getting a conclusive result is smaller than with POVMs. The POVM that gives the highest probability of a conclusive outcome in this task is given by <ref name="bergou">{{cite book |author1= J.A. Bergou |author2=U. Herzog |author3=M. Hillery |editor1=M. Paris |editor2=J. Řeháček |title=Quantum State Estimation |url= https://archive.org/details/quantumstateesti00pari |url-access= limited |date=2004 |publisher=Springer |isbn=978-3-540-44481-7 |pages=[https://archive.org/details/quantumstateesti00pari/page/n420 417]–465 |ref=bergou_book |chapter=Discrimination of Quantum States|doi=10.1007/978-3-540-44481-7_11}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | last=Chefles | first=Anthony | title=Quantum state discrimination | journal=Contemporary Physics | publisher=Informa UK Limited | volume=41 | issue=6 | year=2000 | issn=0010-7514 | doi=10.1080/00107510010002599 | pages=401–424|arxiv=quant-ph/0010114v1| bibcode=2000ConPh..41..401C | s2cid=119340381 }}</ref> |

|||

对抗机器翻译检查器 |

|||

:<math>F_{\psi}=\frac{1}{1+|\lang\varphi|\psi\rang|}|\varphi^\perp\rangle\langle\varphi^\perp| </math> |

|||

:<math>F_{\varphi}=\frac{1}{1+|\lang\varphi|\psi\rang|}|\psi^\perp\rangle\langle\psi^\perp| </math> |

|||

:<math>F_?= \operatorname{I}-F_{\psi}-F_{\varphi}= \frac{2|\lang\varphi|\psi\rang|}{1+|\lang\varphi|\psi\rang|} |\gamma\rangle\langle\gamma|,</math> |

|||

where |

|||

:<math>|\gamma\rangle = \frac1{\sqrt{2(1+|\lang\varphi|\psi\rang|)}}(|\psi\rangle+e^{i\arg(\lang\varphi|\psi\rang)}|\varphi\rangle).</math> |

|||

Note that <math>\operatorname{tr}(|\varphi\rangle\langle\varphi|F_{\psi}) = \operatorname{tr}(|\psi\rangle\langle\psi|F_{\varphi}) = 0</math>, so when outcome <math>\psi</math> is obtained we are certain that the quantum state is <math>|\psi\rangle</math>, and when outcome <math>\varphi</math> is obtained we are certain that the quantum state is <math>|\varphi\rangle</math>. |

|||

对抗机器翻译检查器 |

|||

The probability of having a conclusive outcome is given by |

|||

对抗机器翻译检查器 |

|||

:<math>1-|\lang\varphi|\psi\rang|,</math> |

|||

when the quantum system is in state <math>|\psi\rangle</math> or <math>|\varphi\rangle</math> with the same probability. This result is known as the Ivanović-Dieks-Peres limit, named after the authors who pioneered UQSD research.<ref>{{cite journal | last=Ivanovic | first=I.D. | title=How to differentiate between non-orthogonal states | journal=Physics Letters A | publisher=Elsevier BV | volume=123 | issue=6 | year=1987 | issn=0375-9601 | doi=10.1016/0375-9601(87)90222-2 | pages=257–259| bibcode=1987PhLA..123..257I }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | last=Dieks | first=D. | title=Overlap and distinguishability of quantum states | journal=Physics Letters A | publisher=Elsevier BV | volume=126 | issue=5–6 | year=1988 | issn=0375-9601 | doi=10.1016/0375-9601(88)90840-7 | pages=303–306| bibcode=1988PhLA..126..303D }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | last=Peres | first=Asher | title=How to differentiate between non-orthogonal states | journal=Physics Letters A | publisher=Elsevier BV | volume=128 | issue=1–2 | year=1988 | issn=0375-9601 | doi=10.1016/0375-9601(88)91034-1 | page=19| bibcode=1988PhLA..128...19P }}</ref> |

|||

Since the POVMs are rank-1, we can use the simple case of the construction above to obtain a projective measurement that physically realises this POVM. Labelling the three possible states of the enlarged Hilbert space as <math>|\text{result ψ}\rangle</math>, <math>|\text{result φ}\rangle</math>, and <math>|\text{result ?}\rangle</math>, we see that the resulting unitary <math>U_\text{UQSD}</math> takes the state <math>|\psi\rangle</math> to |

|||

对抗机器翻译检查器 |

|||

:<math>U_\text{UQSD}|\psi\rangle = \sqrt{1-|\lang\varphi|\psi\rang|}|\text{result ψ}\rangle + \sqrt{|\lang\varphi|\psi\rang|} |\text{result ?}\rangle,</math> |

|||

and similarly it takes the state <math>|\varphi\rangle</math> to |

|||

:<math>U_\text{UQSD}|\varphi\rangle = \sqrt{1-|\lang\varphi|\psi\rang|}|\text{result φ}\rangle + e^{-i\arg(\lang\varphi|\psi\rang)}\sqrt{|\lang\varphi|\psi\rang|}|\text{result ?}\rangle.</math> |

|||

A projective measurement then gives the desired results with the same probabilities as the POVM. |

|||

This POVM has been used to experimentally distinguish non-orthogonal polarisation states of a photon. The realisation of the POVM with a projective measurement was slightly different from the one described here.<ref>{{cite journal | author1=B. Huttner | author2 = A. Muller | author3 = J. D. Gautier | author4 = H. Zbinden | author5 = N. Gisin | title=Unambiguous quantum measurement of nonorthogonal states | journal=Physical Review A | publisher=APS | volume=54 | issue=5 | year=1996 | pages = 3783–3789 | doi=10.1103/PhysRevA.54.3783 | pmid = 9913923 | bibcode = 1996PhRvA..54.3783H }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | author1=R. B. M. Clarke | author2 = A. Chefles | author3 = S. M. Barnett | author4 = E. Riis | title=Experimental demonstration of optimal unambiguous state discrimination | journal=Physical Review A | publisher=APS | volume=63 | year=2001 | issue = 4 | doi=10.1103/PhysRevA.63.040305 | page=040305(R) | arxiv=quant-ph/0007063| bibcode = 2001PhRvA..63d0305C | s2cid = 39481893 }}</ref> |

|||

对抗机器翻译检查器 |

|||

对抗机器翻译检查器 |

|||

对抗机器翻译检查器 |

|||

对抗机器翻译检查器 |

|||

对抗机器翻译检查器 |

|||

对抗机器翻译检查器 |

|||

对抗机器翻译检查器 |

|||

对抗机器翻译检查器 |

|||

对抗机器翻译检查器 |

|||

对抗机器翻译检查器 |

|||

对抗机器翻译检查器 |

|||

对抗机器翻译检查器 |

|||

对抗机器翻译检查器 |

|||

== 参见 == |

== 参见 == |

||

2024年4月19日 (五) 15:42的版本

| 此條目目前正依照en:POVM上的内容进行翻译。 (2024年4月19日) |

在泛函分析和量子信息科学中,正算子值测度(POVM)是一种推广的测度,这种测度的值为希尔伯特空间上半正定算子。POVM是投影值测度(PVM) 的推广,相应地,POVM描述的量子测量是PVM描述的量子测量 (称为投影测量) 的推广。

粗略地比喻一下,POVM之于PVM,就如同混合态之于纯态一样。 混合态对于刻画一个较大系统的子系统的状态而言是必须的(见量子态的纯化);类似地,POVM则对于刻画在较大系统上进行的投影测量对子系统的影响是必须的。

POVM是量子力学中最普遍的测量类型,也用于量子场论。[1]它们在量子信息领域有着广泛的应用。

定义

设 是一希尔伯特空间,而 是一可测空间,其中 是 上的博雷尔σ-代数。若 上的一个函数 ,其值为 上的正有界自伴算子,且对于任意 和 满足

则 是σ-代数 上的非负可数可加测度,且总质量为恆等算子 ,那么称 是一个POVM。 [2]

在最简单的情况下,POVM是有限维希尔伯特空间 上的一组半正定埃尔米特矩阵 ,其和为单位矩阵[3] :90

POVM与投影值测度的不同之处在于,对于投影值测量, 必须是正交投影。

在量子力学中,POVM的关键性质是它确定了结果空间上的一个概率测度,因此 可以解释为测量量子态 时得到结果 的概率(密度)。也就是说,POVM元素 是关联于测量结果 的,从而对量子态 进行量子测量时得到它的概率

- ,

其中 是迹运算。若被测量的量子态是纯态 ,则此公式简化为

- 。

POVM的最简单情况推广了PVM的最简单情况,即PVM是一组和为恒等矩阵的正交投影 的情况:

PVM的概率公式与POVM的概率公式相同。一个重要的区别是POVM的元素不一定正交。因此,POVM元素的数量 可以大于其所作用的希尔伯特空间的维数,而PVM元素的数量 不会超过希尔伯特空间的维数。

奈马克扩张定理

奈马克扩张定理[4]展示了如何从作用于更大空间的PVM中得到POVM。这一结果在量子力学中至关重要,因为它提供了一种物理实现正算子值测量的方法。[5] :285

最简单的情况是,POVM元素作用于一个有限维希尔伯特空间且数目有限。奈马克扩张定理指出,若 是 维希尔伯特空间 上的POVM,则存在一个 维希尔伯特空间 上的PVM 以及等距同构 ,使得对于任意 有

对于秩为一的POVM的特殊情况,即存在某(未归一化的)向量 使得 ,该等距映射可以构造为[5] :285

而PVM则由 给出。注意这里 。

一般情况下,等距同构和PVM可以通过定义[6][7] 、 和

来构造。注意这里 ,因此这是一个更加“浪费”的构造。

无论哪种情况,对经过等距映射后的态进行该投影测量得到结果 的概率与进行原始正算子值测量得到该结果的概率相同:

通过将该等距同构 扩张为一个幺正算子 ,可以将这种构造转化为POVM的一个物理实现方案。也就是说寻找 使得

这总是可以做到。

实现对量子态 进行的正算子值测量 的方法是[需要解释],将 嵌入希尔伯特空间 ,然后进行其幺正演化 ,再进行对应于PVM 的投影测量。

测量后的状态

测量后的状态不是由POVM本身决定的,而是由物理上实现它的PVM来决定。由于相同的POVM有无穷个不同的PVM实现,因此 这些算子本身并不能确定测量后的状态。为看出这一点,注意对于任何幺正算子 ,算子

也满足性质 ,那么结合第二种构造的等距同构

也将实现相同的 POVM。在被测状态为纯态 的情况下,由此得到的幺正 在该态(连同辅助态)上的作用结果是

当得到的测量结果为 时,辅助态上的投影测量将会使 坍缩到态[3] :84

若被测态的密度矩阵为 ,其被测量后的状态是

因此可见,测量后状态明确依赖于幺正算子 。注意虽然 总是埃尔米特的, 一般未必是埃尔米特的。

正算子值测量与投影测量的另一个区别在于它通常是不可重复的。若第一次测量得到结果 ,第二次测量得到不同结果 的概率为

- ,

它在 和 不正交时可以是不为零的。在投影测量中,这些算子必然是正交的,因此测量始终是可重复的。

An example: unambiguous quantum state discrimination

Suppose you have a quantum system with a 2-dimensional Hilbert space that you know is in either the state or the state , and you want to determine which one it is. If and are orthogonal, this task is easy: the set will form a PVM, and a projective measurement in this basis will determine the state with certainty. If, however, and are not orthogonal, this task is impossible, in the sense that there is no measurement, either PVM or POVM, that will distinguish them with certainty.[3]:87 The impossibility of perfectly discriminating between non-orthogonal states is the basis for quantum information protocols such as quantum cryptography, quantum coin flipping, and quantum money.

The task of unambiguous quantum state discrimination (UQSD) is the next best thing: to never make a mistake about whether the state is or , at the cost of sometimes having an inconclusive result. It is possible to do this with projective measurements.[8] For example, if you measure the PVM , where is the quantum state orthogonal to , and obtain result , then you know with certainty that the state was . If the result was , then it is inconclusive. The analogous reasoning holds for the PVM , where is the state orthogonal to .

This is unsatisfactory, though, as you can't detect both and with a single measurement, and the probability of getting a conclusive result is smaller than with POVMs. The POVM that gives the highest probability of a conclusive outcome in this task is given by [8][9]

where

Note that , so when outcome is obtained we are certain that the quantum state is , and when outcome is obtained we are certain that the quantum state is .

The probability of having a conclusive outcome is given by

when the quantum system is in state or with the same probability. This result is known as the Ivanović-Dieks-Peres limit, named after the authors who pioneered UQSD research.[10][11][12]

Since the POVMs are rank-1, we can use the simple case of the construction above to obtain a projective measurement that physically realises this POVM. Labelling the three possible states of the enlarged Hilbert space as , , and , we see that the resulting unitary takes the state to

and similarly it takes the state to

A projective measurement then gives the desired results with the same probabilities as the POVM.

This POVM has been used to experimentally distinguish non-orthogonal polarisation states of a photon. The realisation of the POVM with a projective measurement was slightly different from the one described here.[13][14]

参见

参考资料

- ^ Peres, Asher; Terno, Daniel R. Quantum information and relativity theory. Reviews of Modern Physics. 2004, 76 (1): 93–123. Bibcode:2004RvMP...76...93P. S2CID 7481797. arXiv:quant-ph/0212023

. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.76.93.

. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.76.93.

- ^ Davies, Edward Brian. Quantum Theory of Open Systems. London: Acad. Press. 1976: 35. ISBN 978-0-12-206150-9.

- ^ 3.0 3.1 3.2 M. Nielsen and I. Chuang, Quantum Computation and Quantum Information, Cambridge University Press, (2000)

- ^ I. M. Gelfand and M. A. Neumark, On the embedding of normed rings into the ring of operators in Hilbert space, Rec. Math. [Mat. Sbornik] N.S. 12(54) (1943), 197–213.

- ^ 5.0 5.1 A. Peres. Quantum Theory: Concepts and Methods. Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1993.

- ^ J. Preskill, Lecture Notes for Physics: Quantum Information and Computation, Chapter 3, http://theory.caltech.edu/~preskill/ph229/index.html

- ^ J. Watrous. The Theory of Quantum Information. Cambridge University Press, 2018. Chapter 2.3, https://cs.uwaterloo.ca/~watrous/TQI/

- ^ 8.0 8.1 J.A. Bergou; U. Herzog; M. Hillery. Discrimination of Quantum States. M. Paris; J. Řeháček (编). Quantum State Estimation

. Springer. 2004: 417–465. ISBN 978-3-540-44481-7. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-44481-7_11.

. Springer. 2004: 417–465. ISBN 978-3-540-44481-7. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-44481-7_11.

- ^ Chefles, Anthony. Quantum state discrimination. Contemporary Physics (Informa UK Limited). 2000, 41 (6): 401–424. Bibcode:2000ConPh..41..401C. ISSN 0010-7514. S2CID 119340381. arXiv:quant-ph/0010114v1

. doi:10.1080/00107510010002599.

. doi:10.1080/00107510010002599.

- ^ Ivanovic, I.D. How to differentiate between non-orthogonal states. Physics Letters A (Elsevier BV). 1987, 123 (6): 257–259. Bibcode:1987PhLA..123..257I. ISSN 0375-9601. doi:10.1016/0375-9601(87)90222-2.

- ^ Dieks, D. Overlap and distinguishability of quantum states. Physics Letters A (Elsevier BV). 1988, 126 (5–6): 303–306. Bibcode:1988PhLA..126..303D. ISSN 0375-9601. doi:10.1016/0375-9601(88)90840-7.

- ^ Peres, Asher. How to differentiate between non-orthogonal states. Physics Letters A (Elsevier BV). 1988, 128 (1–2): 19. Bibcode:1988PhLA..128...19P. ISSN 0375-9601. doi:10.1016/0375-9601(88)91034-1.

- ^ B. Huttner; A. Muller; J. D. Gautier; H. Zbinden; N. Gisin. Unambiguous quantum measurement of nonorthogonal states. Physical Review A (APS). 1996, 54 (5): 3783–3789. Bibcode:1996PhRvA..54.3783H. PMID 9913923. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.54.3783.

- ^ R. B. M. Clarke; A. Chefles; S. M. Barnett; E. Riis. Experimental demonstration of optimal unambiguous state discrimination. Physical Review A (APS). 2001, 63 (4): 040305(R). Bibcode:2001PhRvA..63d0305C. S2CID 39481893. arXiv:quant-ph/0007063

. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.63.040305.

. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.63.040305.

外部链接

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||