焦虑症:修订间差异

标签:移除或更換文件 |

Charlesorium(留言 | 贡献) 由链接翻译器自动翻译;翻译来源是英文条目 标签:加入不可见字符 |

||

| 第2行: | 第2行: | ||

{{globalize|time=2018-11-29T19:04:20+00:00}} |

{{globalize|time=2018-11-29T19:04:20+00:00}} |

||

{{update|time=2018-11-29T19:04:20+00:00}} |

{{update|time=2018-11-29T19:04:20+00:00}} |

||

{{ |

{{Translating|||time=2020-03-13T04:22:12+00:00}} |

||

}} |

}} |

||

{{medical}} |

{{medical}} |

||

| 第67行: | 第67行: | ||

== 注意 == |

== 注意 == |

||

不光只有单纯的焦虑症才有这些症状,一些精神病症也可能产生焦虑症状,如[[精神分裂症]]、[[强迫症]]等,这类疾病的焦虑症状只是症状之一。無論是精神病学上或是单纯的焦虑症,在临床上的症状都没有本质上的差異,但在治疗上也许比单纯的焦虑症要复杂,因为在治疗其焦虑症状的同时,还要同時治疗此类患者的其他症状,所以,此需要与单纯的焦虑症有所区分。 |

不光只有单纯的焦虑症才有这些症状,一些精神病症也可能产生焦虑症状,如[[精神分裂症]]、[[强迫症]]等,这类疾病的焦虑症状只是症状之一。無論是精神病学上或是单纯的焦虑症,在临床上的症状都没有本质上的差異,但在治疗上也许比单纯的焦虑症要复杂,因为在治疗其焦虑症状的同时,还要同時治疗此类患者的其他症状,所以,此需要与单纯的焦虑症有所区分。 |

||

==种类== |

|||

[[File:A. Morison "Physiognomy of mental diseases", cases Wellcome L0022722 (cropped).jpg|thumb|罹患有慢性焦虑症的某个人,他的表情。]] |

|||

===广泛性焦虑症=== |

|||

{{Main|广泛性焦虑症}} |

|||

广泛性焦虑症({{lang-en|Generalized anxiety disorder}},缩写GAD)是一种常见的障碍,特征是持续的焦虑,并不在某一特定的对象或情境中焦虑。罹患此病的人常常经受不特定却持续的恐惧和忧虑,对日常中的很多事情都过度担心。它的具体表现是慢性的过度忧虑,以下症状至少有三种出现:烦躁不安、虚弱、注意力不集中、易怒、肌肉紧张、睡眠问题。<ref>Schacter, D. L., Gilbert, D. T., & Wegner, D.M. (2011). ''Psychology: Second Edition''. New York, NY: Worth.</ref> Generalized anxiety disorder is the most common anxiety disorder to affect older adults.<ref name="Calleo">{{Cite journal |vauthors=Calleo J, Stanley M |title=Anxiety Disorders in Later Life: Differentiated Diagnosis and Treatment Strategies |journal=Psychiatric Times |volume=26 |issue=8 |year=2008 |url=http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/display/article/10168/1166976 |url-status=live |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20090904032148/http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/display/article/10168/1166976 |archivedate=4 September 2009 |df=dmy-all }}</ref> 焦虑症可能是药物滥用的症状,请医学专家一定注意这一点。一个人可以被诊断为GAD患者,仅当他对日常问题过度担心,达到了六个月及以上。<ref name="Barker2003">{{cite book|author=Phil Barker|title=Psychiatric and mental health nursing: the craft of caring|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=6qdoQgAACAAJ|accessdate=17 December 2010|date=7 October 2003|publisher=Arnold|location=London|isbn=978-0-340-81026-2|url-status=live|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20130527071117/http://books.google.com/books?id=6qdoQgAACAAJ|archivedate=27 May 2013|df=dmy-all}}</ref> 有些患者可能会在日常决策和记忆上出现问题,因为过度焦虑使他的注意力降低。<ref>''Psychology'', Michael Passer, Ronald Smith, Nigel Holt, Andy Bremner, Ed Sutherland, Michael Vliek (2009) McGrath Hill Education, UK: McGrath Hill Companies Inc. p 790</ref> 表面上看起来紧张(strained)并伴随手脚及腋窝出汗,<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.webmd.com/anxiety-panic/guide/mental-health-anxiety-disorders |title=All About Anxiety Disorders: From Causes to Treatment and Prevention |accessdate=2016-02-18 |url-status=live |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20160217225046/http://www.webmd.com/anxiety-panic/guide/mental-health-anxiety-disorders |archivedate=17 February 2016 |df=dmy-all }}</ref> 并且时常哭泣,可能是抑郁症的表现。<ref name=Gelder2005>''Psychiatry'', Michael Gelder, Richard Mayou, John Geddes 3rd ed. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, c 2005 p. 75</ref> 焦虑症诊断前,医师必须排除是药物摄取造成的焦虑。<ref>Varcarolis. E (2010). ''Manual of Psychiatric Nursing Care Planning: Assessment Guides, Diagnoses and Psychopharmacology''. 4th ed. New York: Saunders Elsevier. p 109.</ref> |

|||

儿童GAD可能伴随头痛、烦躁不安、腹部疼痛和心悸等症状,<ref name=PedGAD2009>{{cite journal|last=Keeton|first=CP|author2=Kolos, AC|author3= Walkup, JT|title=Pediatric generalized anxiety disorder: epidemiology, diagnosis, and management.|journal=Paediatric Drugs|year=2009|volume=11|issue=3|pages=171–83|pmid=19445546|doi=10.2165/00148581-200911030-00003}}</ref> 八到九岁时开始最为典型。<ref name=PedGAD2009/> |

|||

===特殊恐惧症=== |

|||

{{Main|特殊恐惧症}} |

|||

焦虑症的最大分支是特殊恐惧症,它是指恐惧和焦虑由特定的刺激或情境导致的病症。全世界大概有5%到12%的人罹患特殊恐惧症。<ref name="Barker2003"/> 患者遇上特定的对象,会有恐惧的预期。这些对象可以是任何事物,从动物到场所,从流体到特定特定情境等等。常见的恐惧症,包括恐惧飞行、血液、水、高速公路和通道等等。当恐惧症发作时,他们可能遭受颤抖、气短、心跳加快等等。<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.mentalhealth.gov/what-to-look-for/anxiety-disorders/phobias/index.html|title=Phobias|last=U.S. Department of Health & Human Services|date=2017|website=www.mentalhealth.gov|language=en-us|access-date=2017-12-01|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170513022004/https://www.mentalhealth.gov/what-to-look-for/anxiety-disorders/phobias/index.html|archive-date=13 May 2017|url-status=dead}}</ref> 人们通常知道他们的恐惧出现时,并没有特定的危险,因此也就不需要这样恐惧,但是仍然,很多人遭受着特殊恐惧症。<ref>''Psychology''. Michael Passer, Ronald Smith, Nigel Holt, Andy Bremner, Ed Sutherland, Michael Vliek. (2009) McGrath Hill Higher Education; UK: McGrath Hill companies Inc.</ref> |

|||

===Panic disorder=== |

|||

{{Main|Panic disorder}} |

|||

With panic disorder, a person has brief attacks of intense terror and apprehension, often marked by trembling, shaking, confusion, dizziness, nausea, and/or difficulty breathing. These [[恐慌發作|恐慌發作]], defined by the [[美國精神醫學學會|APA]] as fear or discomfort that abruptly arises and peaks in less than ten minutes, can last for several hours.<ref>{{cite web|title=Panic Disorder|url=https://www.med.upenn.edu/ctsa/panic_symptoms.html|website=Center for the Treatment and Study of Anxiety, University of Pennsylvania|url-status=live|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20150527074826/http://www.med.upenn.edu/ctsa/panic_symptoms.html|archivedate=27 May 2015|df=dmy-all}}</ref> Attacks can be triggered by stress, irrational thoughts, general fear or fear of the unknown, or even exercise. However, sometimes the trigger is unclear and the attacks can arise without warning. To help prevent an attack one can avoid the trigger. This being said not all attacks can be prevented. |

|||

In addition to recurrent unexpected panic attacks, a diagnosis of panic disorder requires that said attacks have chronic consequences: either worry over the attacks' potential implications, persistent fear of future attacks, or significant changes in behavior related to the attacks. As such, those suffering from panic disorder experience symptoms even outside specific panic episodes. Often, normal changes in heartbeat are noticed by a panic sufferer, leading them to think something is wrong with their heart or they are about to have another panic attack. In some cases, a heightened awareness ([[過度警覺|過度警覺]]) of body functioning occurs during panic attacks, wherein any perceived physiological change is interpreted as a possible life-threatening illness (i.e., extreme [[疑病症|疑病症]]). |

|||

===Agoraphobia=== |

|||

{{Main|Agoraphobia}} |

|||

Agoraphobia is the specific anxiety about being in a place or situation where escape is difficult or embarrassing or where help may be unavailable.<ref>{{harvnb|Craske|2003}} Gorman, 2000</ref> Agoraphobia is strongly linked with [[恐慌症|恐慌症]] and is often precipitated by the fear of having a panic attack. A common manifestation involves needing to be in constant view of a door or other escape route. In addition to the fears themselves, the term [[廣場恐懼症|廣場恐懼症]] is often used to refer to avoidance behaviors that sufferers often develop.<ref>{{cite book |author1= Jane E. Fisher |author2= William T. O'Donohue |title= Practitioner's Guide to Evidence-Based Psychotherapy |date= 27 July 2006 |publisher= Springer |isbn= 978-0387283692 |pages= 754 |df= dmy-all }}</ref> For example, following a panic attack while driving, someone suffering from agoraphobia may develop anxiety over driving and will therefore avoid driving. These avoidance behaviors can often have serious consequences and often reinforce the fear they are caused by. |

|||

===Social anxiety disorder=== |

|||

{{Main|Social anxiety disorder}} |

|||

[[社交恐懼症|社交恐懼症]] (SAD; also known as social phobia) describes an intense fear and avoidance of negative public scrutiny, public embarrassment, humiliation, or social interaction. This [[恐惧|恐惧]] can be specific to particular social situations (such as public speaking) or, more typically, is experienced in most (or all) social interactions. [[社交焦慮|社交焦慮]] often manifests specific physical symptoms, including blushing, sweating, and difficulty speaking. As with all phobic disorders, those suffering from social anxiety often will attempt to avoid the source of their anxiety; in the case of social anxiety this is particularly problematic, and in severe cases can lead to complete social isolation. |

|||

Social physique anxiety (SPA) is a subtype of social anxiety. It is concern over the evaluation of one's body by others.<ref>{{cite book|title=The Oxford Handbook of Exercise Psychology|date=2012|publisher=Oxford University Press|isbn=9780199930746|page=56|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=VR1pAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA56}}</ref> SPA is common among adolescents, especially females. |

|||

===Post-traumatic stress disorder=== |

|||

{{Main|Post-traumatic stress disorder}} |

|||

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) was once an anxiety disorder (now moved to ''trauma- and stressor-related disorders'' in DSM-V) that results from a traumatic experience. Post-traumatic stress can result from an extreme situation, such as combat, natural disaster, rape, hostage situations, child abuse, bullying, or even a serious accident. It can also result from long-term (chronic) exposure to a severe stressor--<ref>{{Cite book | title=Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and the Family | publisher=Veterans Affairs Canada | url=http://www.vac-acc.gc.ca/clients/sub.cfm?source=mhealth/ptsd_families# | isbn=978-0-662-42627-1 | year=2006 | url-status=live | archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20090214122623/http://www.vac-acc.gc.ca/clients/sub.cfm?source=mhealth%2Fptsd_families | archivedate=14 February 2009 | df=dmy-all }}</ref> for example, soldiers who endure individual battles but cannot [[因應 (心理學)|cope]] with continuous combat. Common symptoms include [[過度警覺|過度警覺]], {{tsl|en|Flashback (psychological phenomenon)||flashbacks}}, avoidant behaviors, anxiety, anger and depression.<ref name="psycho-prat">[http://www.psycho-prat.fr/index.php?module=webuploads&func=download&fileId=2963_0 Psychological Disorders] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20081204123458/http://www.psycho-prat.fr/index.php?module=webuploads&func=download&fileId=2963_0 |date=4 December 2008 }}, Psychologie Anglophone</ref> In addition, individuals may experience sleep disturbances.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Shalev|first1=Arieh|last2=Liberzon|first2=Israel|last3=Marmar|first3=Charles|title=Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder|journal=New England Journal of Medicine|volume=376|issue=25|pages=2459–2469|doi=10.1056/nejmra1612499|pmid=28636846|year=2017}}</ref> There are a number of treatments that form the basis of the care plan for those suffering with PTSD. Such treatments include [[认知行为疗法|认知行为疗法]] (CBT), psychotherapy and support from family and friends.<ref name="Barker2003"/> |

|||

[[創傷後壓力症候群|創傷後壓力症候群]] (PTSD) research began with Vietnam veterans, as well as natural and non natural disaster victims. Studies have found the degree of exposure to a disaster has been found to be the best predictor of PTSD.<ref>{{Cite book|title = Posttraumatic Stress Disorder|last = Fullerton|first = Carol|publisher = American Psychiatric Press Inc.|year = 1997|isbn = 978-0-88048-751-1|location = Washington, D.C.|pages = 8–9}}</ref> |

|||

===Separation anxiety disorder=== |

|||

{{Main|Separation anxiety disorder}} |

|||

Separation anxiety disorder (SepAD) is the feeling of excessive and inappropriate levels of anxiety over being separated from a person or place. Separation anxiety is a normal part of development in babies or children, and it is only when this feeling is excessive or inappropriate that it can be considered a disorder.<ref>Siegler, Robert (2006). ''How Children Develop, Exploring Child Develop Student Media Tool Kit & Scientific American Reader to Accompany How Children Develop''. New York: Worth Publishers. {{ISBN|0-7167-6113-0}}.</ref> Separation anxiety disorder affects roughly 7% of adults and 4% of children, but the childhood cases tend to be more severe; in some instances, even a brief separation can produce panic.<ref>{{cite journal|title=Adult Separation Anxiety Often Overlooked Diagnosis – Arehart-Treichel 41 (13): 30 – Psychiatr News |journal=Psychiatric News |volume=41 |issue=13 |pages=30 |doi=10.1176/pn.41.13.0030 |year = 2006|last1 = Arehart-Treichel|first1 = Joan}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal| last1 = Shear | first1 = K. | last2 = Jin | first2 = R. | last3 = Ruscio | first3 = AM. | last4 = Walters | first4 = EE. | last5 = Kessler | first5 = RC. | title = Prevalence and correlates of estimated DSM-IV child and adult separation anxiety disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication | journal = Am J Psychiatry | volume = 163 | issue = 6 | pages = 1074–1083 |date=June 2006 | doi = 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.6.1074 | pmid = 16741209 | pmc = 1924723 }}</ref> Treating a child earlier may prevent problems. This may include training the parents and family on how to deal with it.<!-- <ref name=Moh2014/> --> Often, the parents will reinforce the anxiety because they do not know how to properly work through it with the child.<!-- <ref name=Moh2014/> --> In addition to parent training and family therapy, medication, such as SSRIs, can be used to treat separation anxiety.<ref name=Moh2014>{{Cite journal|last=Mohatt|first=Justin|last2=Bennett|first2=Shannon M.|last3=Walkup|first3=John T.|date=2014-07-01|title=Treatment of Separation, Generalized, and Social Anxiety Disorders in Youths|journal=American Journal of Psychiatry|volume=171|issue=7|pages=741–748|doi=10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13101337|pmid=24874020|issn=0002-953X}}</ref> |

|||

===Situational anxiety=== |

|||

Situational anxiety is caused by new situations or changing events. It can also be caused by various events that make that particular individual uncomfortable. Its occurrence is very common. Often, an individual will experience panic attacks or extreme anxiety in specific situations. A situation that causes one individual to experience anxiety may not affect another individual at all. For example, some people become uneasy in crowds or tight spaces, so standing in a tightly packed line, say at the bank or a store register, may cause them to experience extreme anxiety, possibly a panic attack.<ref>Situational Panic Attacks. (n.d.). Retrieved from {{cite web |url=http://www.sound-mind.org/situational-panic-attacks.html |title=Situational Panic Attacks |accessdate=2013-03-28 |url-status=live |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20120610035242/http://www.sound-mind.org/situational-panic-attacks.html |archivedate=10 June 2012 |df=dmy-all }}</ref> Others, however, may experience anxiety when major changes in life occur, such as entering college, getting married, having children, etc. |

|||

===Obsessive–compulsive disorder=== |

|||

{{Main|Obsessive–compulsive disorder}} |

|||

Obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) is not classified as an anxiety disorder by the {{tsl|en|DSM-5||}} but is by the ICD-10. It was previously classified as an anxiety disorder in the DSM-IV. It is a condition where the person has [[固著 (心理學)|obsession]]s (distressing, persistent, and intrusive thoughts or images) and [[強迫行為|compulsions]] (urges to repeatedly perform specific acts or rituals), that are not caused by drugs or physical order, and which cause distress or social dysfunction.<ref name="NICE-2006">{{cite book|last1=National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health|first1=(UK)|title=Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Core Interventions in the Treatment of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder and Body Dysmorphic Disorder|journal=NICE Clinical Guidelines|date=2006|issue=31|pmid=21834191|url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedhealth/PMH0015812/|accessdate=21 November 2015|url-status=live|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20130529141531/http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedhealth/PMH0015812/|archivedate=29 May 2013|df=dmy-all|isbn=9781854334305}}</ref><ref name="Soomro-2012">{{cite journal|last1=Soomro|first1=GM|title=Obsessive compulsive disorder.|journal=BMJ Clinical Evidence|date=18 January 2012|volume=2012|pmid=22305974|pmc=3285220}}</ref> The compulsive rituals are personal rules followed to relieve the feeling of discomfort.<ref name="Soomro-2012" /> OCD affects roughly 1–2% of adults (somewhat more women than men), and under 3% of children and adolescents.<ref name="NICE-2006" /><ref name="Soomro-2012" /> |

|||

A person with OCD knows that the symptoms are unreasonable and struggles against both the thoughts and the behavior.<ref name="NICE-2006" /><ref name="IQWiG-2014">{{cite web|last1=Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG)|title=Obsessive-compulsive disorder: overview|url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedhealth/PMH0072746/|website=PubMed Health|publisher=Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG)|accessdate=21 November 2015}}</ref> Their symptoms could be related to external events they fear (such as their home burning down because they forget to turn off the stove) or worry that they will behave inappropriately.<ref name="IQWiG-2014" /> |

|||

It is not certain why some people have OCD, but behavioral, cognitive, genetic, and neurobiological factors may be involved.<ref name="Soomro-2012" /> Risk factors include family history, being single (although that may result from the disorder), and higher socioeconomic class or not being in paid employment.<ref name="Soomro-2012" /> Of those with OCD about 20% of people will overcome it, and symptoms will at least reduce over time for most people (a further 50%).<ref name="NICE-2006" /> |

|||

===Selective mutism=== |

|||

{{Main|Selective mutism}} |

|||

Selective mutism (SM) is a disorder in which a person who is normally capable of speech does not speak in specific situations or to specific people. Selective mutism usually co-exists with [[羞怯|羞怯]] or [[社交焦慮|社交焦慮]].<ref>{{Cite journal | last1 = Viana | first1 = A. G. | last2 = Beidel | first2 = D. C. | last3 = Rabian | first3 = B. | doi = 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.09.009 | title = Selective mutism: A review and integration of the last 15 years | journal = Clinical Psychology Review | volume = 29 | issue = 1 | pages = 57–67 | year = 2009 | pmid = 18986742 | pmc = }}</ref> People with selective mutism stay silent even when the consequences of their silence include shame, social ostracism or even punishment.<ref>[https://www.nytimes.com/2005/04/12/health/psychology/12mute.html "The Child Who Would Not Speak a Word"] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150403040319/http://www.nytimes.com/2005/04/12/health/psychology/12mute.html |date=3 April 2015 }}</ref> Selective mutism affects about 0.8% of people at some point in their life.<ref name="Lancet2016"/> |

|||

== 種類 == |

== 種類 == |

||

2020年3月13日 (五) 04:22的版本

| 焦慮症 Anxiety disorder | |

|---|---|

| |

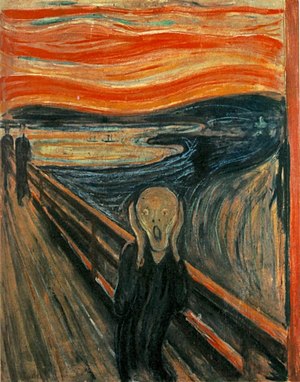

| 挪威畫家愛德華·孟克的畫作《吶喊》[1] | |

| 症状 | 擔心、心跳过速、顫抖[2] |

| 併發症 | 重度抑郁症、失眠、生活品質變差、自殺[3] |

| 常見始發於 | 15–35 歲[4] |

| 病程 | > 6 個月[2][4] |

| 类型 | 认知障碍[*]、疾病 |

| 肇因 | 遺傳 與 環境因素[5] |

| 风险因子 | 虐待兒童、家族病史、貧窮[4] |

| 相似疾病或共病 | 甲状腺功能亢进症; 心血管疾病; 咖啡因、酒精、大麻 使用; 突然停止使用一些藥物導致的身體應變不及之反應[4][6] |

| 治療 | 改變生活習慣與認知、心理治療、藥物[4] |

| 藥物 | 抗抑郁药、anxiolytics, Β受体阻滞剂[5] |

| 盛行率 | 12%[4][7] |

| 分类和外部资源 | |

| 醫學專科 | 精神病学、臨床心理學 |

| ICD-9-CM | 300.09 |

| OMIM | 607834 |

| DiseasesDB | 787 |

| eMedicine | 286227 |

| 焦虑症 | |

|---|---|

| 类型 | 认知障碍[*]、疾病 |

| 治療 | 心理治療 |

| 分类和外部资源 | |

| 醫學專科 | 精神病学 |

| ICD-10 | F40-F42 |

| ICD-9-CM | 300 |

| OMIM | [1] |

| DiseasesDB | 787 |

| eMedicine | med/152 |

| MeSH | D001008 |

焦虑症或稱焦急症(英文:anxiety disorder)是明顯感覺焦慮和恐懼感的一種精神疾病[2]。焦慮是對未來事件的擔心,恐懼則是對當前事件的反應[2],這些感覺可能會導致身體症狀,如心跳過速和顫抖[2]。以下為常見的焦慮症:廣泛性焦慮症、特異性恐懼症、社交焦慮症、分離焦慮症、廣場恐懼症、恐慌症和選擇性緘默症[2]。焦虑症會由造成症狀的原因來區分[2],人們往往有不止一種的焦慮症[2]。

遺傳與環境都可能是造成導致焦慮的原因[5],孩童時期遭受虐待、家族有精神病史以及貧窮都有可能是焦慮症的危險因子[4]。焦慮症常常和其他精神疾病一同發生,像是:重性抑郁障碍、人格異常或是成癮症[4],要診斷焦慮症至少需要六個月的臨床觀察,在特定狀況導致異於常人的過度焦慮,並影響正常生活[2][4]。另外,甲状腺功能亢进症、心臟病、使用咖啡因、嗜酒、滥用大麻或是處於勒戒某些藥物的狀態,都有可能出現類似焦慮症的症狀[4][6]。

焦慮症如果不治療,一般不會自行復原[2][5]。治療方法包含改變生活型態、尋求諮商,以及藥物控制[4]。諮商一般會配合認知行為療法進行治療[4]。可改善症狀的藥物則包含抗抑鬱藥、抗焦虑药(如現代常用:苯二氮䓬类药物、β受体阻断剂、丁螺環酮)等等[5]。

全球大約12%的人口患有焦慮症,5~30%的人在一生中至少患有一次焦慮症[4][7]女性的發生率約為男性的兩倍,且通常自25歲以前就開始發作[2][4]。最常見的為對於特定事物的恐懼症,將近12%的人在一生中的某個時候曾有此類問題,社交焦慮症則占了10%[4]。患病者通常介於15至35歲之間,且年紀通常不會超過55歲[4]。歐美的發生率較其他地方為高[4]。

症状

患者的情绪表现的非常不安与恐惧,患者常常对现实生活中的某些事情或将来的某些事情表现的过分担忧,有时患者也可以无明确目标的担忧。这种担心往往是与现实极不相称的,使患者感到非常的痛苦。还伴有自主神经亢进,肌肉紧张或跳動等自律神經失調的症状。

病因

精神心理因素,许多学者认为焦虑症状的形成与思维和认知过程有着密切的、重要的关系。研究表明,一些人更愿把一些普通的事情,甚至是一些良性的事情解释为灾难的先兆。例如,人们高神经质[8]。 这与抑郁情绪的产生也有一些联系。还有就是生化的因素,例如甲状腺的病症或神经化学递质功能失调的因素所致。

治疗

焦虑症的治疗一为药物治疗,用抗焦虑药物去平静脑中过度活跃的部份。另一方面为认知行为治疗,找出生活中的压力源,避开压力,学习放松技巧,减轻压力。

另外维持血糖值的稳定有助于稳定情绪,脑中缺乏血糖作燃料就容易暴躁焦虑。补充营养例如维他命B群、钙,多食用深海鱼油、青菜等,配合适当的运动,都有助于降低焦虑症。

注意

不光只有单纯的焦虑症才有这些症状,一些精神病症也可能产生焦虑症状,如精神分裂症、强迫症等,这类疾病的焦虑症状只是症状之一。無論是精神病学上或是单纯的焦虑症,在临床上的症状都没有本质上的差異,但在治疗上也许比单纯的焦虑症要复杂,因为在治疗其焦虑症状的同时,还要同時治疗此类患者的其他症状,所以,此需要与单纯的焦虑症有所区分。

种类

广泛性焦虑症

广泛性焦虑症(英語:Generalized anxiety disorder,缩写GAD)是一种常见的障碍,特征是持续的焦虑,并不在某一特定的对象或情境中焦虑。罹患此病的人常常经受不特定却持续的恐惧和忧虑,对日常中的很多事情都过度担心。它的具体表现是慢性的过度忧虑,以下症状至少有三种出现:烦躁不安、虚弱、注意力不集中、易怒、肌肉紧张、睡眠问题。[9] Generalized anxiety disorder is the most common anxiety disorder to affect older adults.[10] 焦虑症可能是药物滥用的症状,请医学专家一定注意这一点。一个人可以被诊断为GAD患者,仅当他对日常问题过度担心,达到了六个月及以上。[11] 有些患者可能会在日常决策和记忆上出现问题,因为过度焦虑使他的注意力降低。[12] 表面上看起来紧张(strained)并伴随手脚及腋窝出汗,[13] 并且时常哭泣,可能是抑郁症的表现。[14] 焦虑症诊断前,医师必须排除是药物摄取造成的焦虑。[15]

儿童GAD可能伴随头痛、烦躁不安、腹部疼痛和心悸等症状,[16] 八到九岁时开始最为典型。[16]

特殊恐惧症

焦虑症的最大分支是特殊恐惧症,它是指恐惧和焦虑由特定的刺激或情境导致的病症。全世界大概有5%到12%的人罹患特殊恐惧症。[11] 患者遇上特定的对象,会有恐惧的预期。这些对象可以是任何事物,从动物到场所,从流体到特定特定情境等等。常见的恐惧症,包括恐惧飞行、血液、水、高速公路和通道等等。当恐惧症发作时,他们可能遭受颤抖、气短、心跳加快等等。[17] 人们通常知道他们的恐惧出现时,并没有特定的危险,因此也就不需要这样恐惧,但是仍然,很多人遭受着特殊恐惧症。[18]

Panic disorder

With panic disorder, a person has brief attacks of intense terror and apprehension, often marked by trembling, shaking, confusion, dizziness, nausea, and/or difficulty breathing. These 恐慌發作, defined by the APA as fear or discomfort that abruptly arises and peaks in less than ten minutes, can last for several hours.[19] Attacks can be triggered by stress, irrational thoughts, general fear or fear of the unknown, or even exercise. However, sometimes the trigger is unclear and the attacks can arise without warning. To help prevent an attack one can avoid the trigger. This being said not all attacks can be prevented.

In addition to recurrent unexpected panic attacks, a diagnosis of panic disorder requires that said attacks have chronic consequences: either worry over the attacks' potential implications, persistent fear of future attacks, or significant changes in behavior related to the attacks. As such, those suffering from panic disorder experience symptoms even outside specific panic episodes. Often, normal changes in heartbeat are noticed by a panic sufferer, leading them to think something is wrong with their heart or they are about to have another panic attack. In some cases, a heightened awareness (過度警覺) of body functioning occurs during panic attacks, wherein any perceived physiological change is interpreted as a possible life-threatening illness (i.e., extreme 疑病症).

Agoraphobia

Agoraphobia is the specific anxiety about being in a place or situation where escape is difficult or embarrassing or where help may be unavailable.[20] Agoraphobia is strongly linked with 恐慌症 and is often precipitated by the fear of having a panic attack. A common manifestation involves needing to be in constant view of a door or other escape route. In addition to the fears themselves, the term 廣場恐懼症 is often used to refer to avoidance behaviors that sufferers often develop.[21] For example, following a panic attack while driving, someone suffering from agoraphobia may develop anxiety over driving and will therefore avoid driving. These avoidance behaviors can often have serious consequences and often reinforce the fear they are caused by.

Social anxiety disorder

社交恐懼症 (SAD; also known as social phobia) describes an intense fear and avoidance of negative public scrutiny, public embarrassment, humiliation, or social interaction. This 恐惧 can be specific to particular social situations (such as public speaking) or, more typically, is experienced in most (or all) social interactions. 社交焦慮 often manifests specific physical symptoms, including blushing, sweating, and difficulty speaking. As with all phobic disorders, those suffering from social anxiety often will attempt to avoid the source of their anxiety; in the case of social anxiety this is particularly problematic, and in severe cases can lead to complete social isolation.

Social physique anxiety (SPA) is a subtype of social anxiety. It is concern over the evaluation of one's body by others.[22] SPA is common among adolescents, especially females.

Post-traumatic stress disorder

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) was once an anxiety disorder (now moved to trauma- and stressor-related disorders in DSM-V) that results from a traumatic experience. Post-traumatic stress can result from an extreme situation, such as combat, natural disaster, rape, hostage situations, child abuse, bullying, or even a serious accident. It can also result from long-term (chronic) exposure to a severe stressor--[23] for example, soldiers who endure individual battles but cannot cope with continuous combat. Common symptoms include 過度警覺, flashbacks, avoidant behaviors, anxiety, anger and depression.[24] In addition, individuals may experience sleep disturbances.[25] There are a number of treatments that form the basis of the care plan for those suffering with PTSD. Such treatments include 认知行为疗法 (CBT), psychotherapy and support from family and friends.[11]

創傷後壓力症候群 (PTSD) research began with Vietnam veterans, as well as natural and non natural disaster victims. Studies have found the degree of exposure to a disaster has been found to be the best predictor of PTSD.[26]

Separation anxiety disorder

Separation anxiety disorder (SepAD) is the feeling of excessive and inappropriate levels of anxiety over being separated from a person or place. Separation anxiety is a normal part of development in babies or children, and it is only when this feeling is excessive or inappropriate that it can be considered a disorder.[27] Separation anxiety disorder affects roughly 7% of adults and 4% of children, but the childhood cases tend to be more severe; in some instances, even a brief separation can produce panic.[28][29] Treating a child earlier may prevent problems. This may include training the parents and family on how to deal with it. Often, the parents will reinforce the anxiety because they do not know how to properly work through it with the child. In addition to parent training and family therapy, medication, such as SSRIs, can be used to treat separation anxiety.[30]

Situational anxiety

Situational anxiety is caused by new situations or changing events. It can also be caused by various events that make that particular individual uncomfortable. Its occurrence is very common. Often, an individual will experience panic attacks or extreme anxiety in specific situations. A situation that causes one individual to experience anxiety may not affect another individual at all. For example, some people become uneasy in crowds or tight spaces, so standing in a tightly packed line, say at the bank or a store register, may cause them to experience extreme anxiety, possibly a panic attack.[31] Others, however, may experience anxiety when major changes in life occur, such as entering college, getting married, having children, etc.

Obsessive–compulsive disorder

Obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) is not classified as an anxiety disorder by the DSM-5 but is by the ICD-10. It was previously classified as an anxiety disorder in the DSM-IV. It is a condition where the person has obsessions (distressing, persistent, and intrusive thoughts or images) and compulsions (urges to repeatedly perform specific acts or rituals), that are not caused by drugs or physical order, and which cause distress or social dysfunction.[32][33] The compulsive rituals are personal rules followed to relieve the feeling of discomfort.[33] OCD affects roughly 1–2% of adults (somewhat more women than men), and under 3% of children and adolescents.[32][33]

A person with OCD knows that the symptoms are unreasonable and struggles against both the thoughts and the behavior.[32][34] Their symptoms could be related to external events they fear (such as their home burning down because they forget to turn off the stove) or worry that they will behave inappropriately.[34]

It is not certain why some people have OCD, but behavioral, cognitive, genetic, and neurobiological factors may be involved.[33] Risk factors include family history, being single (although that may result from the disorder), and higher socioeconomic class or not being in paid employment.[33] Of those with OCD about 20% of people will overcome it, and symptoms will at least reduce over time for most people (a further 50%).[32]

Selective mutism

Selective mutism (SM) is a disorder in which a person who is normally capable of speech does not speak in specific situations or to specific people. Selective mutism usually co-exists with 羞怯 or 社交焦慮.[35] People with selective mutism stay silent even when the consequences of their silence include shame, social ostracism or even punishment.[36] Selective mutism affects about 0.8% of people at some point in their life.[4]

種類

需要區分的心理疾病

参考文献

- ^ Peter Aspden. So, what does ‘The Scream’ mean?. Financial Times. 2012-04-21.

- ^ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental DisordersAmerican Psychiatric Associati. 5th. Arlington: American Psychiatric Publishing. 2013: 189–195. ISBN 978-0890425558.

- ^ Anxiety disorders - Symptoms and causes. Mayo Clinic. [23 May 2019] (英语).

- ^ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 4.14 4.15 4.16 4.17 Craske, MG; Stein, MB. Anxiety.. Lancet. 24 June 2016. PMID 27349358. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30381-6.

- ^ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Anxiety Disorders. NIMH. March 2016 [14 August 2016]. (原始内容存档于27 July 2016).

- ^ 6.0 6.1 Testa A, Giannuzzi R, Daini S, Bernardini L, Petrongolo L, Gentiloni Silveri N. Psychiatric emergencies (part III): psychiatric symptoms resulting from organic diseases (PDF). Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci (Review). 2013,. 17 Suppl 1: 86–99. PMID 23436670. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于10 March 2016).

- ^ 7.0 7.1 Kessler; et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of mental disorders in the World Health Organization’s World Mental Health Survey Initiative. World Psychiatry. 2007, 6 (3): 168–76. PMC 2174588

. PMID 18188442.

. PMID 18188442.

- ^ Jeronimus B.F.; Kotov, R.; Riese, H.; Ormel, J. Neuroticism's prospective association with mental disorders halves after adjustment for baseline symptoms and psychiatric history, but the adjusted association hardly decays with time: a meta-analysis on 59 longitudinal/prospective studies with 443 313 participants. Psychological Medicine. 2016. PMID 27523506. doi:10.1017/S0033291716001653.

- ^ Schacter, D. L., Gilbert, D. T., & Wegner, D.M. (2011). Psychology: Second Edition. New York, NY: Worth.

- ^ Calleo J, Stanley M. Anxiety Disorders in Later Life: Differentiated Diagnosis and Treatment Strategies. Psychiatric Times. 2008, 26 (8). (原始内容存档于4 September 2009). 已忽略未知参数

|df=(帮助) - ^ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Phil Barker. Psychiatric and mental health nursing: the craft of caring. London: Arnold. 7 October 2003 [17 December 2010]. ISBN 978-0-340-81026-2. (原始内容存档于27 May 2013). 已忽略未知参数

|df=(帮助) - ^ Psychology, Michael Passer, Ronald Smith, Nigel Holt, Andy Bremner, Ed Sutherland, Michael Vliek (2009) McGrath Hill Education, UK: McGrath Hill Companies Inc. p 790

- ^ All About Anxiety Disorders: From Causes to Treatment and Prevention. [2016-02-18]. (原始内容存档于17 February 2016). 已忽略未知参数

|df=(帮助) - ^ Psychiatry, Michael Gelder, Richard Mayou, John Geddes 3rd ed. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, c 2005 p. 75

- ^ Varcarolis. E (2010). Manual of Psychiatric Nursing Care Planning: Assessment Guides, Diagnoses and Psychopharmacology. 4th ed. New York: Saunders Elsevier. p 109.

- ^ 16.0 16.1 Keeton, CP; Kolos, AC; Walkup, JT. Pediatric generalized anxiety disorder: epidemiology, diagnosis, and management.. Paediatric Drugs. 2009, 11 (3): 171–83. PMID 19445546. doi:10.2165/00148581-200911030-00003.

- ^ U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Phobias. www.mentalhealth.gov. 2017 [2017-12-01]. (原始内容存档于13 May 2017) (美国英语).

- ^ Psychology. Michael Passer, Ronald Smith, Nigel Holt, Andy Bremner, Ed Sutherland, Michael Vliek. (2009) McGrath Hill Higher Education; UK: McGrath Hill companies Inc.

- ^ Panic Disorder. Center for the Treatment and Study of Anxiety, University of Pennsylvania. (原始内容存档于27 May 2015). 已忽略未知参数

|df=(帮助) - ^ Craske 2003 Gorman, 2000

- ^ Jane E. Fisher; William T. O'Donohue. Practitioner's Guide to Evidence-Based Psychotherapy. Springer. 27 July 2006: 754. ISBN 978-0387283692. 已忽略未知参数

|df=(帮助) - ^ The Oxford Handbook of Exercise Psychology. Oxford University Press. 2012: 56. ISBN 9780199930746.

- ^ Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and the Family. Veterans Affairs Canada. 2006. ISBN 978-0-662-42627-1. (原始内容存档于14 February 2009). 已忽略未知参数

|df=(帮助) - ^ Psychological Disorders 互联网档案馆的存檔,存档日期4 December 2008., Psychologie Anglophone

- ^ Shalev, Arieh; Liberzon, Israel; Marmar, Charles. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. New England Journal of Medicine. 2017, 376 (25): 2459–2469. PMID 28636846. doi:10.1056/nejmra1612499.

- ^ Fullerton, Carol. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Press Inc. 1997: 8–9. ISBN 978-0-88048-751-1.

- ^ Siegler, Robert (2006). How Children Develop, Exploring Child Develop Student Media Tool Kit & Scientific American Reader to Accompany How Children Develop. New York: Worth Publishers. ISBN 0-7167-6113-0.

- ^ Arehart-Treichel, Joan. Adult Separation Anxiety Often Overlooked Diagnosis – Arehart-Treichel 41 (13): 30 – Psychiatr News. Psychiatric News. 2006, 41 (13): 30. doi:10.1176/pn.41.13.0030.

- ^ Shear, K.; Jin, R.; Ruscio, AM.; Walters, EE.; Kessler, RC. Prevalence and correlates of estimated DSM-IV child and adult separation anxiety disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Am J Psychiatry. June 2006, 163 (6): 1074–1083. PMC 1924723

. PMID 16741209. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.163.6.1074.

. PMID 16741209. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.163.6.1074.

- ^ Mohatt, Justin; Bennett, Shannon M.; Walkup, John T. Treatment of Separation, Generalized, and Social Anxiety Disorders in Youths. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2014-07-01, 171 (7): 741–748. ISSN 0002-953X. PMID 24874020. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13101337.

- ^ Situational Panic Attacks. (n.d.). Retrieved from Situational Panic Attacks. [2013-03-28]. (原始内容存档于10 June 2012). 已忽略未知参数

|df=(帮助) - ^ 32.0 32.1 32.2 32.3 National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, (UK). Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Core Interventions in the Treatment of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder and Body Dysmorphic Disorder. 2006 [21 November 2015]. ISBN 9781854334305. PMID 21834191. (原始内容存档于29 May 2013). 已忽略未知参数

|df=(帮助);|journal=被忽略 (帮助);|issue=被忽略 (帮助) - ^ 33.0 33.1 33.2 33.3 33.4 Soomro, GM. Obsessive compulsive disorder.. BMJ Clinical Evidence. 18 January 2012, 2012. PMC 3285220

. PMID 22305974.

. PMID 22305974.

- ^ 34.0 34.1 Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG). Obsessive-compulsive disorder: overview. PubMed Health. Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG). [21 November 2015].

- ^ Viana, A. G.; Beidel, D. C.; Rabian, B. Selective mutism: A review and integration of the last 15 years. Clinical Psychology Review. 2009, 29 (1): 57–67. PMID 18986742. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2008.09.009.

- ^ "The Child Who Would Not Speak a Word" 互联网档案馆的存檔,存档日期3 April 2015.

外部連結

- (英文) Generalized Anxiety Disorder Symptoms

- (英文) Mental Health Matters: General Anxiety Disorder

- (英文) Psych Forums: General Anxiety Forum

- (英文) Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD): Symptoms, Causes, and Treatment

- (英文) Article: Understanding Generalized Anxiety Disorders[永久失效連結]

- (英文) Anxiety Zone - Anxiety Disorders Support

- (英文) AuroraMD provides Primary Care screening services

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||