思覺失調症

| 思覺失調症 Schizophrenia | |

|---|---|

| |

| 經診斷患有思覺失調症的人所刺繡的衣服 | |

| 讀音 |

|

| 症狀 | 思維形式障礙、妄想、幻覺等[2][3] |

| 起病年齡 | 16~30歲[3] |

| 病程 | 持續一段長時間[3] |

| 類型 | 精神病性障礙、思覺失調症譜系障礙[*]、疾病 |

| 病因 | 環境及遺傳因子[4] |

| 風險因素 | 家族史、吸食大麻、於胎內發展時出現問題、在城市中長大、擁有較大年紀的父親[4][5] |

| 診斷方法 | 依據求診者所表現出來的行為及其所主訴的個人經歷作診斷[6] |

| 鑑別診斷 | 物質濫用、情感障礙、亨丁頓舞蹈症、自閉症[7] |

| 治療 | 輔導、職業培訓[4][2] |

| 藥物 | 抗精神病藥[4] |

| 預後 | 鑑於患者自殺以及患上心臟病等文明病的風險增加[8],所以其預期壽命下降了18~20年[9][8] |

| 盛行率 | ~0.5%[10] |

| 死亡數 | ~17,000(2015)[11] |

| 分類和外部資源 | |

| 醫學專科 | 精神科 |

| ICD-11 | 6A20 |

| ICD-10 | F20 |

| ICD-9-CM | 295.9、295.90、295 |

| OMIM | 181500 |

| DiseasesDB | 11890 |

| MedlinePlus | 000928 |

| eMedicine | 288259、805988 |

思覺失調症(schizophrenia,中國大陸、香港稱精神分裂症)是一種常見的重性精神障礙[12][13],屬精神病性障礙大類[14]。其典型症狀為精神病性症狀(psychosis)[2],即無法區分真實與虛幻[15],且伴有多種精神狀態的紊亂,涉及思維(如妄想、思維形式紊亂)、感知(如幻覺)、自我體驗(如感覺、衝動、思想或行為受外力控制的體驗)、認知(如注意力、語言記憶和社會認知受損)、意志力(如動機喪失)、情感(如情緒表達遲鈍)和行為(如怪異或無目的的行為、不可預測或不適當的干擾行為組織的情緒反應)[16]。思覺失調症常與其他精神障礙共病,例如焦慮症、嚴重憂鬱疾患或藥物濫用障礙等[17]。症狀通常逐漸地出現,且一般在成年早期開始,並持續一段長時間[3][6]。

思覺失調症的成因包括環境因子及遺傳因子[4]。可能的環境因子包括在城市中長大、濫用娛樂性藥物、某些傳染病、父母年齡,和自身在母體內時營養攝取不足[4][18]。遺傳因子則包括各種常見和罕見的遺傳變異[19]。思覺失調症可依據求診者所表現出來的行為及其所主訴的個人經歷作診斷[6]。在診斷時,還必須把求診者的文化背景納入考慮範圍之內[6]。截至2013年為止,此病並沒有任何客觀的測試予供作診斷[6]。思覺失調症完全不同於解離性身分疾患(舊稱「多重人格障礙症」,俗稱「人格分裂」)——這種混淆的想法常在公眾的認知中出現[20]。

治療的重心是為患者處方抗精神病藥,以及安排諮詢、工作培訓和社會康復[2][4]。目前尚不清楚典型抗精神病藥與非典型抗精神病藥兩者間哪種的效果會較佳[21]。在其他抗精神病藥物都無法改善病情的情況下,就可能會使用氯氮平。必要時,可能會強制患者住院治療,如患者可能會對自身或他人構成傷害這一種情況,但現在的住院時間比以往更為短暫,且強制住院治療的總次數亦較為少[22]。

世界人口中約0.3~0.7%在其一生中受思覺失調症所影響[10] 。2019年,全球估計有2000萬名思覺失調症患者[23]。男性比女性更常受到思覺失調症的影響[2],且其病情也一般較嚴重。大約20%的人康復得很好,一些人亦能完全康復[6];50%的人則終生受到一定程度的影響[24]。患者常伴有一定的社會問題,例如長期失業、貧窮和無家可歸[6][25]。患有思覺失調症的人的平均預期壽命比平均值少10年至25年[9]。其背後原因是患者的身體健康問題增加和自殺率較高(約5%)[10][26]。在2015年,全球估計有17,000人死於與思覺失調症有關或由其引起的行為[11]。

名稱

[編輯]1896年,德國精神病學家Kraepelin因該障礙多起病於青少年且以衰退為結局,將其命名為「早發性失智症」[12][13]。1911年,瑞士學者Bleuler研究認為核心問題是人格的分裂,提出了「精神分裂」(splitting of mind)的概念,又因預後並不一定是衰退,故建議命名為「精神分裂症」[12]。該障礙的英文名「schizophrenia」即移植自新拉丁文,詞根是希臘語「skhizein」(意為「分裂」)與「phrēn」(意為「精神」)[27]。漢字文化圈過去都曾直譯作「精神分裂症」,後來台灣改稱「思覺失調症」[28][29][30],日本改稱「統合失調症」[31];香港則仍將此障礙稱作「精神分裂症」,而使用「思覺失調」一詞指代「psychosis」[32](台灣、中國大陸譯「精神病」)或「early psychosis」[33](台灣、中國大陸無專名)。

症狀

[編輯]

思覺失調症患者可能會出現的症狀包括幻覺(以幻聽最為多見)、妄想(以被害妄想與關係妄想最為多見),以及思維和言語紊亂。思維和言語紊亂的程度可從較輕微的思維不清晰,以至較嚴重的胡言亂語。患者亦普遍出現社交退縮、對穿衣和衛生不感興趣,以及失去動力和判斷力的情況[34][35]。

思覺失調症患者亦常見出現自我體驗異常的症狀,例如認為一些想法或感覺不是真正屬於自己的,而是他者所植入的,這種症狀有時稱為「被動體驗」[36]。常在患者身上觀察出情感性疾患,例如缺乏積極的情緒反應[37]。社會認知障礙也與思覺失調症有關[38],例如患者所表現出來的多疑症狀。患者亦常面臨社會孤立。普遍患者還在以下範疇出現困難:工作記憶、長期記憶和學習、管控功能、注意力[10]。在一種罕見的亞型中,患者會經常保持緘默、在異常姿勢中保持不動,或者表現出亳無理由的興奮狀態——都是緊張性憂鬱障礙的症狀[39]。患者亦會發現自己對面部表情的感知存有一定困難[40]。部分患者會出現思想阻斷的現象,亦即其在說話時會突然停頓數秒至數分[41][42]。

大約30%至50%的思覺失調症患者不能接受自己患病的事實,或遵從推薦予他們的治療[43]。思覺失調症的治療可能會對患者的洞察力産生一些影響[44]。

思覺失調症患者可能比一般人有較高的比率患上大腸激躁症,但除非特別提及此一問題,否則他們通常不會特別指出[45]。精神性多渴症在思覺失調症患者中相對較普遍[46]。

正性及負性症狀

[編輯]思覺失調症通常以正性及負性症狀來描述[47]。正性症狀是大多數人通常不會遇到的症狀,但存在於思覺失調症患者中。這包括妄想、思維和言語紊亂,以及在五感上存有幻覺——這些通常被認為是精神病的表現[48]。幻覺通常與妄想的主題內容有關[49]。藥物對治療患者的正性症狀十分有效[49]。

負性症狀是指正常情緒反應或其他思維過程中所存有的一些缺陷,藥物對治療負性症狀的效果較差[35]。其包括缺乏情感或情緒淡然(Reduced affect display)、貧語症(Alogia)、享樂不能(Anhedonia,快樂不起來)、無社會性(Asociality)和動機缺乏(Avolition)。與正性症狀相比,負性症狀對他人的負擔、患者的生活品質以及工作能力的影響較大[50]。擁有較為嚴重的負性症狀的患者在發病之前通常具有適應不良的生活史,並且藥物對其治療效果通常亦是十分有限[35][51]。

多於一項的變量分析研究對「正性及負性」這一區分表示質疑,並按其觀察把症狀分成三個維度。儘管用語會有所差異,但大多會將其分成人格解體、幻覺及負性症狀[52]。

認知功能障礙

[編輯]一般認為認知能力的缺陷是思覺失調症的核心特徵[53][54][55]。患者的認知缺陷程度是個體功能、工作表現的品質,以及維持治療效度的預測因素[56]。認知功能障礙的存在及其程度是一項比起正性或負性症狀更為良好的指標去評估個體功能[53]。受認知功能缺陷所影響的範疇十分廣泛,其中包括工作記憶、長期記憶[57][58]、口語敘述記憶[59]、語意處理過程[60]、情節記憶[56] 、注意力[24] 、學習能力(特別是語言學習)[57]。在思覺失調症患者中最明顯的是言語記憶的缺陷,並且不是由注意力不足所致。言語記憶障礙與患者的語意編碼能力(即處理與意義有關的信息的能力)下降有關,其被視為長期記憶缺陷的另一已知原因[57]。當給予受試者上面寫有一列單詞的列表時,健康的人會較常記住一些意思積極的詞語(此現象稱為波麗安娜效應);然而,思覺失調症患者傾向於不管其涵意如何,一概記住所有詞語,這表明失去愉悅感會使患者對詞語的語義編碼能力受損[57]。這些缺陷在患者的病情發展至某種程度前就能發現[53][55][61]。思覺失調症患者的一等親和其他高危群體亦表現出一定程度的認知能力缺陷,特別是在工作記憶上[61]。關於思覺失調症患者的認知缺陷的文獻綜述顯示,該缺陷可能在青春期早期,或早至兒童期時就已經存在[53]。即使隨著時間的推移,認知缺陷在大多數患者中仍傾向保持原來的樣子,少部分患者或因基於環境變數的可識別原因而改變[53][57]。

雖然「隨著時間的推移,認知缺陷仍傾向保持原來的樣子」的證據是可靠和充分的[56][57],但在這個領域的大部分研究都集中於提高注意力和工作記憶的方法[57][58]。研究人員曾利用「設立較高或較低的獎賞」以及「提供教育與否」等環境變數去嘗試改善患者的學習能力,結果顯示:較高的獎賞會使患者的表現更差,而提供教育則能改善患者的表現,這顯示可能存在一些改善認知表現的治療[57]。可通過口語表達訓練,改善患者的思維、注意力和語言行為;亦可通過認知複誦(cognitive rehearsal),給予患者自我教導(self-instructions),其能使患者在處理困擾的處境時有一套應對表現,以及令在患者在成功時自我強化(self-reinforcement):這都能顯著提高回憶任務(recall tasks)的表現[57]。這種類型的訓練稱為「自我教導訓練」(self-instructional training),它所產生的好處包括能使患者毫無意義的言語減少,以及改善患者的回憶能力和注意力[57]。

發病

[編輯]青春期晚期至成年人早期是思覺失調症發病的高峰[10],這亦是青壯年人社會和職業發展的關鍵年齡[62]。經診斷患有思覺失調症的人中,分別有40%和23%的男性及女性在19歲之前就表現出該病的症狀[63]。思覺失調症的症狀一般在16-30歲期間首次出現[3][6]。大多男性患者在18-25歲期間發病,女性患者則大多在25-35歲之間發病[64]。為了讓與思覺失調症相關的發展障礙的程度減至最低,研究人員已經進行了許多用以鑑定和治療該病的前驅期的研究,使思覺失調症在早至發病前30個月就能發現[62]。在發病前,當事人可能會經歷可以自我控制或短暫的思覺失調症狀[65],和社交退縮、易怒、煩躁不安、動作笨拙這些非特異性症狀[66][67]。發展思覺失調症的兒童可能會有的表現包括智力下降、動作發展遲緩、偏好於獨自玩樂、社交焦慮和學習成績差[68][69][70]。

病因

[編輯]思覺失調症是一種典型的多基因遺傳病,病因複雜[71][72],受遺傳因素和環境因素共同影響[20][10]。

遺傳因子

[編輯]據估計,思覺失調症的遺傳度為80%,這表示80%的思覺失調症個體患病風險差異可由基因方面的差異來解釋[73]。該些估計的差異很大,因為難以把遺傳因子和環境因子的影響區分[74]。發病的最大單一危險因子是一等親(包括父母、子女和手足)中有人患有思覺失調症(風險為6.5%);若同卵雙胞胎中其中一方是思覺失調症患者,另一方則有超過40%的機會也受到思覺失調症的影響[20]。如果雙親中其中一位患有思覺失調症,其子女患上思覺失調症的風險約為13%;如果雙親分別都患有思覺失調症,風險則將近50%[73]。若急性短暫性精神病患者擁有與思覺失調症有關的家族病患史,其在一年後診斷為思覺失調症的機率約有20%-40%[75]。有關思覺失調症候選基因的研究結果一般不能找到一致的相關性[76]。

目前已知許多基因與思覺失調症有關,每組都對思覺失調症有少許的影響,以及人類現時尚末完全了解每組基因的傳遞和表達[19][77]。多基因遺傳評分的結果顯示,該些基因最少可以解釋7%思覺失調症的易患性變異[78]。約5%的思覺失調症個案可部分歸因於罕見的拷貝數變異,包括22q11、1q21以及16p11[79]。該些罕見的拷貝數變異會使個體發展思覺失調症的機會增加最多20倍,當事人亦常伴發自閉症和智能障礙[79]。

2018年6月,《科學》期刊發表一篇統合分析初步發現,思覺失調症和雙相障礙、重鬱症、注意力不足過動症有許多共同的可能致病基因[80]。2024年,大腦轉錄組學相關研究提示,要發展出思覺失調症、雙相障礙和自閉症類群障礙等精神障礙,女性比男性可能需要更多遺傳因素與環境因素共同作用[81]。

環境因子

[編輯]與思覺失調症的病發相關的環境因子包括生活環境、使用藥物,以及產前壓力[10]。

母體應激跟患上思覺失調症的風險增加有關,而這可能是絡絲蛋白所致的[82]。孕婦營養缺乏和肥胖皆可能是思覺失調症的風險因子。現有證據亦表明母體壓力及感染會令像白血球介素-8和腫瘤壞死因子般的促發炎蛋白質產生,繼而影響胎兒的神經發展[83][84]。

雖然養育方式對思覺失調症的病發並沒有任何重大的影響,但擁有鼓勵型的父母的人,在與擁有批評型或敵對型的父母的人相比之下,他日後的病發機會更低[20]。在兒時心靈受創、父母死亡、成為欺凌或辱罵對象的人,其日後罹患思覺失調症的風險會增加[85][86]。即使考慮到像吸毒、種族和社會群體規模般的因素[87],在城市環境中渡過童年生活的人或住在城市的成年人,罹患思覺失調症的風險仍會增加至原本的兩倍[20][10]。其他重要因素包括社會孤立、社會逆境相關的移民、種族歧視、家庭困難、失業,和居住條件惡劣[20][88]。

已有假設指出,在一些人當中,思覺失調症的病發與腸道功能障礙有關,例如非乳糜瀉的麩質敏感或腸道菌群異常[89]。思覺失調症患者亞組對麩質的免疫反應不同於乳糜瀉患者,麩質過敏症患者的某些血清生物標誌物會升高,例如抗麥醇溶蛋白IgG或抗麥醇溶蛋白IgA[5]。

吸食毒品

[編輯]大約一半的思覺失調症患者吸毒、濫藥或攝取過多的酒精[90]。安非他命、古柯鹼和較小程度的酒精可導致短暫的刺激性精神障礙或與酒精相關的精神障礙,其與思覺失調症十分類似[20][91]。思覺失調症患者使用尼古丁的速度比普通人群高出許多,雖然這通常不認定為病因[92]。

酒精濫用可能會通過誘發機制,引起活性物質所致的慢性精神障礙[93]。 但使用酒精與早年發病的精神障礙並不相關[94]。

大麻可能是思覺失調症的其中一個誘發因素[18][95][96]。其可能會令高危人士患上思覺失調症[96]。患病風險可能在配合某些基因的情況下才會增加[96],或可能與先前存在的精神病理有關[18]。早年接觸大麻與患病風險的增加密切相關[18]。所增加的程度仍是末知[97],但患上精神障礙的風險估計是增加了2-3倍[95]。吸食較高劑量的大麻以及吸食頻率較高這兩項因素與患上慢性精神障礙的風險增加有關[95]。

患者亦有可能為了消除憂鬱、焦慮、無聊和孤獨這一些負面情緒,而濫用其他藥物[90][98]。

發育因素

[編輯]若胎兒在母體內發育期間經受缺氧不良因素影響,則可能會增加患上思覺失調症的風險[10]。經診斷確實患上思覺失調症的人更可能在冬季或春季出生(至少在北半球情況如是),其可能是胎兒接觸病毒所致[20]。患病風險因此會增加約5%-8%[99]。若懷孕期間或出生時胎兒受到像弓形體般的病原體所感染,其日後的患病機會增加[100]。

病理機制

[編輯]儘管思覺失調症的病理機制尚是不明,但研究人員已經進行了許多嘗試去解釋大腦功能改變和思覺失調症之間的關係[10]。當中最常見的解釋就是多巴胺假說,該假説把精神病中所出現的心智缺陷解釋成是因多巴胺能神經元(dopaminergic neurons)異常所致[10]。其他可能的機轉則涉及到神經遞質穀氨酸和神經發展過程。現有框架已假設該些生理上的異常與症狀是相關的[101]。

研究者依據急性精神病期間患者的多巴胺水平會上升,及影響多巴胺受體的藥物對治療思覺失調症是有效果的觀察,來把多巴胺信號異常跟思覺失調症劃上聯繫[102][103]。此外他們亦假設多巴胺信號異常為患者出現妄想的根本原因[104][105][106]。患者前額葉皮質的多巴胺受體D1水平下降可能為工作記憶能力減退的原因[107][108][109][110]。

現有各種證據支持NMDA受體信號會在思覺失調症患者中減退。研究表明,NMDA受體的表達減少和NMDA受體阻滯劑的運用能夠模擬思覺失調症的症狀及與其有關的生理異常[111][112][113]。屍檢研究一致證實該些神經元的亞型除了形態異常外,亦不能表達GAD67[114]。在工作記憶任務中須進行的神經元集群同步會運用到某些中間神經元,而該些中間神經元在思覺失調症患者中出現異常[114][115][116][117]。

證據也顯示神經發育異常會對思覺失調症的發病存有影響。思覺失調症患者在發病以前一般就已出現了認知障礙、社會功能障礙、運動技能障礙[118]。像母體內感染[119][120]、孕婦營養不良、懷孕期間出現併發症般的問題皆會使胎兒於日後患上思覺失調症的風險增加[83]。思覺失調症一般始發於18-25歲期間——這跟某些與思覺失調症相關的神經發展階段重疊[121]。

思覺失調症患者常出現管控功能方面(包括計劃能力、抑制能力、工作記憶能力)的缺陷。儘管該些功能為可分離的,但患者在相關方面出現障礙這點,可能反映了其工作記憶中表達目標相關信息的能力下降,且在利用它來指導認知和行為方面出現困難[122][123]。該些障礙與許多神經影像學和神經病理學上的異常有關。譬如功能性神經成像研究已發現患者的神經處理有效性減少的證據:他們的背外側前額葉需激活至相對較高的水平,才能應付與工作記憶任務有關的控制。該些異常可能跟眾驗屍結果中所發現的神經氈密度減少有關——後者可透過錐狀細胞密度增加和樹突棘密度減少來證明。這些細胞和功能異常也可能反映在結構性神經影像學研究中,該些研究發現與工作記憶任務表現相關的灰質體積減少[124]。

研究已把正性及負性症狀跟顳上葉及前額葉基底部的腦皮質厚度減少劃上聯繫[125][126]。儘管文獻上經常會形容思覺失調症患者是享樂不能的,然而大量證據表明思覺失調症患者的享樂反應仍然完好[127],並指享樂不能是反映了與獎勵有關的其他過程存有障礙[128]。總體而言,儘管思覺失調症患者的享樂反應完好,但獎勵預測機制可能存有缺陷,使其欠缺動機[129]。

診斷

[編輯]思覺失調症是根據美國精神醫學學會的精神疾病診斷與統計手冊第五版(DSM-5)或世界衛生組織的國際疾病和相關健康問題統計分類(ICD-10)中的標準而作診斷。這些標準的依據為求診者所主訴的個人經歷和他人對求診者的異常行為描述,之後由精神衛生專業人員進行臨床評估。在診斷前,與思覺失調症相關的症狀必須在患者中不斷發生,並需達到一定的嚴重程度[20]。截至2013年為止,此病並沒有任何客觀的測試予供作診斷[6]。

標準

[編輯]2013年,美國精神醫學學會發布了精神疾病診斷與統計手冊第五版。必須在至少一個月的大部分時間內滿足兩項診斷標準,以及至少六個月對社會或職業功能有顯著影響,才能診斷求診者患有思覺失調症。若要診斷成患有思覺失調症,必須具有以下症狀中的其中一項:妄想、幻覺或言語散亂。其他用以作診斷的症狀包括負性症狀、緊張性行為或行為紊亂[130]。定義基本上與2000年的精神疾病診斷與統計手冊(DSM-IV-TR)相同,但是第五版做出了許多改變。

- 亞型分類——如偏執型或緊張型思覺失調症等,都遭到去除。這些在以前的修訂中得以保留的原因是基於慣例,但後來經事實證明,亞型在疾病的治療上是沒有價值的[131]。

- 僵直症不再與思覺失調症密切相關[132]。

- 在對思覺失調症患者的病程進行描述時,建議更好地區分病症的當前狀態及其過去發展,令整體描述更為清楚[131]。

- 不再建議對施耐德主要症狀(Schneider's first-rank symptoms)進行特殊治療[131]。

- 為了更明確地把分裂情感性障礙與思覺失調症劃分,故完善了分裂情感性障礙的定義[131]。

- 它向醫護人員推薦了一項涵蓋精神病理學八個領域的評估,用以幫助臨床決策[133]。

在歐洲國家,ICD-10的診斷標準較為常用;在美國和世界各地,DSM的診斷標準則較ICD-10的常用,並廣泛應用於研究中。ICD-10的診斷標準更為重視施耐德主要症狀。在醫學實踐中,兩套系統之間的一致性很高。[134]目前正在草擬中的ICD-11,提倡在關於思覺失調症的診斷標準中添加「自體疾患」(self-disorder)這一種症狀[36]。

如果困擾患者的症狀存在超過一個月,但少於六個月,則應診斷為類思覺失調症。若精神症狀持續不到一個月,則可能診斷為短暫精神病,患者所擁有的各種症狀則可歸類為未特指的思覺失調症。如果情感性症狀與分裂症狀併存,則會診斷為分裂情感性障礙。如果精神上的症狀是一般醫學病症或物質所直接導致的,則診斷為繼發性精神障礙[130]。如果求診者出現廣泛性發展障礙的症狀,則不能診斷為思覺失調症,除非求診者還明顯地出現了妄想或幻覺等症狀[130]。

亞型

[編輯]DSM-5已刪去DSM-IV中提出的所有亞型[135]。DSM-IV-TR中所包含的五個亞型如下[136][137]:

- 偏執型:又稱妄想型,患者出現妄想和幻覺,但是沒有出現思維障礙、行為紊亂或是情感淡漠。妄想的主題是也許是把事物誇張化,亦有可能令患者感到受迫害。(DSM代碼:295.3/ICD代碼:F20.0)

- 紊亂型:在ICD中稱作青春型,症狀既有思想障礙,亦有情感淡漠,嚴重時可出現無法閱讀文章,觀看電影電視的情況。認知能力雖然在服藥後會得到改善,但與患病前不可同日而語。認知能力損害是對患者影響最大的症狀。(DSM代碼:295.1/ICD代碼:F20.1)

- 緊張型:患者幾乎僵直不動或者過於興奮,漫無目的地行動,以及臉部表情和軀體動作異常,症狀還包括緊張型木僵或蠟狀屈曲(waxy flexibility)、模仿別人說話及動作等。(DSM代碼:295.2/ICD代碼:F20.2)

- 未分型:存在精神症狀,但是不符合上面幾種分類(DSM代碼:295.9/ICD代碼:F20.3)

- 殘餘型:正性症狀僅以輕度的形式存在(DSM代碼:295.6/ICD代碼:F20.5)

ICD-10中所包含的亞型[136]:

- 思覺失調症後憂鬱症:思覺失調症發病以後所出現的憂鬱發作,當中仍存有輕度思覺失調症的症狀。(ICD代碼:F20.4)

- 單純型:負性症狀隱匿地持續發展,在此以前沒有精神病發作史。(ICD代碼:F20.6)

俄羅斯版的ICD-10中亦包含了呆滯型思覺失調症,而其屬於ICD-10第5章F21節——「分裂型」障礙這一索引欄目中[138]。

鑑別診斷

[編輯]幾種不同的精神障礙的患者之中亦有可能出現跟思覺失調症患者類似的心理症狀,包括邊緣性人格障礙症[139]、躁鬱症[140]、物質誘發的精神病、藥物中毒。妄想症、迴避性人格障礙症、類精神思覺失調人格障礙症違常、社交焦慮症的社會退縮等,亦會令該病的患者出現「妄想」這一種症狀(非怪異妄想)。類精神思覺失調人格障礙症違常的症狀與思覺失調症類似,但相對而言不太嚴重[6]。雖然思覺失調症患者伴發強迫症的常見程度遠高於可用「巧合」來解釋,但難以區分強迫症中所出現的強迫觀念和思覺失調症中所出現的妄想[141]。一些人不再服用苯二氮卓類藥物後,會出現可持續一段長時間的嚴重戒斷症狀。戒斷症狀類似於思覺失調症,故有可能因此而誤診[142]。

可能需要進行更全面的醫學和神經學檢查,以排除求診者患上跟思覺失調症的臨床表現差異不大的疾病,如代謝疾病、全身性感染、梅毒、人類免疫缺陷病毒感染、癲癇、邊緣性腦炎、大腦損傷。中風、多發性硬化症、甲狀腺功能亢進症、甲狀腺機能低下症以及像阿茲海默病、亨丁頓舞蹈症、額顳失智症、路易氏體失智症般的失智症的表現皆可能類以於思覺失調症[143]。可能有必要排除求診者出現譫妄,其可通過幻視、急性發作以及知覺水平波動這些特點與思覺失調症區分,亦能把它視為求診者患上其他潛在性疾病的跡象。除非思覺失調症患者有特殊的醫學徵兆或可能對抗精神病藥物存有不良反應,否則通常不會復發。對處於兒童階段的求診者而言,專業人員必須把典型的童年幻想跟幻覺分開看待[6]。

預防

[編輯]思覺失調症是難以預防的,因為沒有可靠的跡象可用於鑑定病發的後期階段[144]。已有初步證據指出早期介入對預防思覺失調症是有效果的[145]。雖然有一些證據指出,對精神病患者實施早期介入可能會有短期的影響,但五年後這些介入幾乎沒有對患者産生任何益處[10]。試圖在前驅期就嘗試預防思覺失調症的益處並不確定,因此截至2009年為止也不推薦施行[146]。實施認知行為治療一年後,可能會降低高風險人士患上精神病的風險[147],故此英國國家健康與照顧卓越研究院推薦在高風險人士中實施該種療法[148]。另一項預防措施是避免接觸與發病相關的藥物,包括大麻、古柯鹼和安非他命[20]。

病情管理

[編輯]思覺失調症的治療重心是為患者處方抗精神病藥物,一般會在此基礎上配合心理及社會支援輔導[10]。當患者嚴重發作時,可能會自願地或強制性地住院(如果當地的精神衛生相關法律條文允許強制住院)。長期住院在現在而言是十分罕見的,因為醫療體系從50年代開始去機構化(Deinstitutionalisation),但長期住院的情況現今仍會發生[22]。社區支援服務包括入住康復中心、社區心理健康團隊的成員訪問、就業能力復康訓練[149]。一些證據表明,定期運動對思覺失調症患者的身體和精神健康有一定幫助[150]。截至2015年,穿顱磁刺激對思覺失調症的治療效果尚不明確[151]。

思覺失調症是中華人民共和國衛生健康委定義的六種嚴重精神障礙之一(其他五種分別是情感思覺失調症、偏執性精神病、雙相(情感)障礙、癲癇所致精神障礙、精神發育遲滯伴發精神障礙)[152]。

藥物治療

[編輯]

思覺失調症的一線治療是為患者處方抗精神病藥物[153],其可在約7至14天內把正性症狀的程度減輕[153]。然而,抗精神病藥物對負性症狀和認知功能障礙的改善效果並不顯著[51][154]。若患者持續實行藥物治療,便可降低復發的風險[155][156]。極少證據顯示他們實行藥物治療超過兩三年後的效果會怎樣[156]。然而抗精神病藥物可導致患者對多巴胺過敏,增加患者一旦停藥後出現症狀的機會[157]。

選用抗精神病藥物時應考慮它的成效、風險和成本[10]。典型和非典型抗精神病藥物之間那種的效果較佳這點至今仍有爭議[21][158]。氨磺必利(Amisulpride)、奧氮平(Olanzapine)、理思必妥(Risperidone)、氯氮平的效果可能會較佳,但這些藥物也與較大的副作用相關[159]。當以低至中等的劑量使用典型抗精神病藥物時,其症狀復發率和中途放棄率會與非典型抗精神病藥物相同[160]。40-50%的個案對藥物治療的反應良好,30-40%的個案在藥物治療後症狀部分緩解,治療抵抗的則有20%(在服用2-3種不同的抗精神病藥六週後症狀仍沒得到令人滿意的改善)[51]。氯氮平能有效治療對其他藥物反應差的個案(治療抵抗性思覺失調症或難治性思覺失調症)[161]。但它在不到4%的人中會導致一種嚴重的可能副作用——粒細胞缺乏症(低白血球計數)[20][10][162]。

大多數接受藥物治療的患者都會受到藥物的副作用所影響。服用典型抗精神病藥物的患者擁有更高的比率出現一種由藥物引發的副作用——錐體外症候群,而一些非典型抗精神病藥物與體重大幅增加,患上糖尿病及代謝症候群的風險上升相關;這在服用奧氮平的情況下最為明顯,理思必妥和喹硫平則與體重增加相關[159]。理思必妥與氟哌啶醇這兩種藥物引起錐體外症候群的比率類似[159]。目前尚不清楚新一代的抗精神病藥物能否降低誘發抗精神藥物惡性症候群或遲發性運動障礙(罕見但嚴重的神經性障礙)的機會[163]。

針對不願意或不能定期服用藥物的患者,可以使用長效抗精神病藥物控制病情[164]。與口服藥物相比,長效抗精神病藥物能以更大的程度去降低復發的風險[155]。當與心理社會一同介入時,它們可能會改善患者對治療的長期依從性[164]。美國精神醫學學會建議,若患者一年以上沒出現任何與思覺失調症有關的症狀,則可考慮停藥[156]。

除了針對多巴胺系統之外,SEP-363856是近年研究發現能夠針對TAAR1跟5-HT1A受器的抗精神病藥物。SEP-363856在研究中能夠降低負性症狀,以及改善睡眠狀況。[165]

社會心理治療

[編輯]許多社會心理介入手段可能有助於治療思覺失調症,包括家庭治療[166]、積極性社區治療、就業協助、認知矯正治療[167]、技能培訓、 代幣制治療,以及針對物質使用和體重管理的社會心理介入[168]。家庭治療或教育能解決患者的家庭問題,這樣可能會減少患者復發和住院的機會[166]。極少證據顯示認知行為治療(CBT)在預防復發或減輕復發的症狀這方面是有效的[169][170]。後設認知訓練的證據結果不一,一些綜述的結論認為其能產生益處,一些則認為不能[171][172][173]。沒有較佳質量的研究支持藝術或戲劇治療的有效性[174][175]。當與正常治療配合時,音樂療法能改善精神狀態和社會功能[176]。

預後

[編輯]

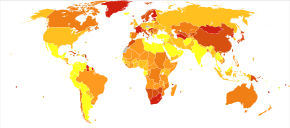

| 無數據 ≤ 185 185–197 197–207 207–218 218–229 229–240 | 240–251 251–262 262–273 273–284 284–295 ≥ 295 |

思覺失調症花費了龐大的人力和經濟成本[10]。它會使患者的預期壽命降低10-25年[9]。這主要是因為它與肥胖、飲食不良、坐式生活型態以及吸菸有關,自殺率的增加亦起了較小的作用[10][9][177]。抗精神病藥物也可能增加預期壽命降低的風險[9]。患者的預期壽命在20世紀70年代至90年代間增加[178]。

思覺失調症是身心障礙的主要原因之一,精神病是排在四肢癱瘓和失智症之後第三常見的身心障礙,並比截癱和失明常見[179]。大約四分之三的思覺失調症患者伴有其他持續性復發的身心障礙[51]。全球有1670萬名患者被認為患有中度或重度的身心障礙[180]。有些患者能完全康復及使其他社會功能維持良好狀態[181]。大多數思覺失調症患者在社區支持下獨立生活[10]。約85%的患者失業[4]。在第一次精神病發作的人中,42%的患者有良好的長期預後結果;預後結果一般的有35%;預後結果不佳的則有27%[182]。有研究顯示開發中國家的預後結果會比已開發國家更好[183],但這項結論備受質疑[184][185]。

思覺失調症患者的自殺率高於平均水平。據引證為10%,但是一項較以上引證新的分析將估計值修改成4.9%,自殺最常發生在發病或首次住院後的一段時間[26][186]。20%至40%的患者至少嘗試自殺一次[6][187]。有著各種各樣的自殺高危因子,包括患者是男性、伴發憂鬱症和擁有高智商這些特點[187]。

全世界的研究都顯示,思覺失調症和吸菸之間擁有著強烈的關係[188][189]。在診斷出思覺失調症的人中,抽菸的比例較一般人口高:普通人群中只有20%是經常抽菸者,思覺失調症患者中則估計達80%至90%[189]。他們更傾向於大量地抽菸,以及抽具有高尼古丁含量的香菸[190]。一些證據表明偏執型思覺失調症患者在獨立生活和職業功能上,可能比患上其他類型的思覺失調症的人更為有展望[191]。思覺失調症患者使用大麻的情況亦頗為常見[90]。

流行病學

[編輯]

全世界約有0.3-0.7%人口[10]——相當於2019年全世界約2000萬人[23]——在其一生中受思覺失調症所影響。男性的發生率比女性高1.4倍,亦通常較早病發[20](發病的高峰年齡男性25歲,女性27歲[192])。童年發病的患者較為罕見[193],罕見的程度和中年或老年發病者相當[194]。

雖然以前認為思覺失調症在世界各地的發生率差不多,但事實上其發生率在世界各地[6][195]、各國家[196]以及各地區[197]都有不同。估計相差可達五倍[4]。全球失能調整生命年中的約1%是由它所導致[20],它亦在2010年令20,000人死亡[198]。對思覺失調症的定義不同這一點,可使其發生率相差達三倍[10]。

2000年,世界衛生組織發現,受思覺失調症影響的人口百分比和每年的新病例數在全世界大致相同。經過年齡標準化後,每10萬男性的盛行率:最低為非洲(343人),最高為大洋洲和日本(544人);每10萬女性的盛行率:最低亦為非洲(378人),最高為東南歐(527人)[199]。在美國,大約1.1%的成年人患有思覺失調症[200]。

歷史

[編輯]

在20世紀初,精神病學家庫爾特·施奈德把一些他認為能使思覺失調症與其他精神障礙區分的症狀列出。這些症狀後來稱為「首級症狀」(first-rank symptoms)或「施耐德主要症狀」(Schneider's first-rank symptoms)。當中包括外源所控制的妄想、思想抽離、思想插入、思想廣播、聽見評論自己的思想或行為的幻聽,或能與幻聽溝通[201]。雖然施耐德主要症狀對當前的診斷標準有很大的貢獻,但其特異性仍受到質疑。一份對1970年至2005年間進行的診斷研究回顧發現,施耐德的聲稱應不需再確認或受到反對,並且建議在未來所修訂的診斷系統中應強調施耐德主要症狀[202]。缺少施耐德主要症狀的患者亦應懷疑其是否真的患上思覺失調症[36]。

思覺失調症的歷史具有一定複雜性,且不容易利用線性敘事的方式展述[203]。雖然類思覺失調症在19世紀以前的歷史記錄中是較為罕見的,但不合理、不可理解或不受控制的行為記錄則較為常見。1797年關於詹姆斯·蒂利·馬修斯的病例詳細報告,以及菲利普·皮內爾於1809年所發表的報告,一般認為是在醫學和精神病學文獻中最早出現的思覺失調症個案[204]。1886年,德國精神病學家海因里希·舒勒(Heinrich Schule)首次使用拉丁文用語「dementia praecox」(早發失智症)這一術語去稱呼現在的思覺失調症。其後阿諾德·皮克於1891年在他的精神障礙病例報告中使用了它。1893年,埃米爾·克雷佩林借用了皮克和舒勒所使用的術語,並於1899年在精神疾病分類中區分了早發失智症和情緒障礙(躁狂憂鬱症,包括單相性和雙相性憂鬱症)[205]。他認為早發失智症可能是由長期系統性的疾病或全人疾病所引起的,其影響身體的許多器官和周圍神經,但其最終會於青春期後在一連串決定性的事件中影響大腦[206]。他亦利用了「praecox」(早發的)這一術語去把其與其他形式的失智症如阿爾茨海默病作區分,阿爾茨海默病通常在年老的人身上發生[207]。有時大眾會認為1852年法國醫生班尼迪克·莫萊爾(Bénédict Morel)使用「démenceprécoce」這一術語可視同醫學上對思覺失調症的發現,然而,這項想法忽略了一個事實:在十九世紀末,沒有什麼可以把莫萊爾所使用的描述性術語跟早發失智症的獨立病發這一概念聯繫起來[208]。

「Schizophrenia」一詞可以直譯作「分裂的心智」,它的希臘詞根是schizein(撕裂)和phren(心智)[209],以往中國大陸、台灣和香港的名稱「精神分裂症」皆是直譯此而來[28],台灣後來則改稱為「思覺失調症」[29]。歐根·布洛伊勒於1908年第一次提出了這個概念,用來描述人格、思想、記憶、知覺之間的功能分離。美國人和英國人把布洛伊勒的宣稱理解成他在形容思覺失調症的「4A」症狀:情緒淡然(flattened Affect)、自閉(Autism)、聯想障礙(impaired Association)、情感矛盾(Ambivalence)[210][211]。 布洛伊勒意識到這一種疾病並不是失智症,因為他的一些患者的病情是在改善,而不是惡化,因此提議以「Schizophrenia」稱呼這一疾病。在50年代中期,因氯丙嗪的研發和引入,而使思覺失調症的治療徹底改變[212]。

在20世紀70年代初,思覺失調症的診斷標準出現了不少爭議,最終修訂成現今所使用的標準。1971年美英診斷學大會發現美國的思覺失調症患者要比歐洲多很多[213],部分是因為美國使用的DSM-II診斷標準比起歐洲的ICD-9更為寬鬆。大衛·羅森漢於1972年進行並於《科學》期刊發表的著名研究——《精神病房裡的正常人》(On being sane in insane places),指出美國的思覺失調症診斷標準往往過於主觀且不可靠[214]。這項研究不僅使思覺失調症的診斷標準得以修正,還令整本DSM手冊得以修訂,使得美國精神醫學學會於1980年時出版DSM-III[215]。

「精神分裂症」這一用語通常誤解成受其影響的人擁有「多重的人格」。雖然一些診斷出思覺失調症的人可能會聽見不存在的聲音,並把其視為獨特的人格,但思覺失調症並不牽涉到在多個人格中轉換。這一種混淆的想法部分可歸因於布洛伊勒的用語「精神分裂症」的字面解釋(布洛伊勒最初將思覺失調症與解離症狀聯繫 起來,並且在他的思覺失調症分類中包含人格分裂)[216][217]。在DSM-II中,解離性人格疾患也常常誤診成思覺失調症,因為其標準診斷較為寬鬆[217][218]。第一位已知誤用該詞的人是一名叫托馬斯·斯特恩斯·艾略特的詩人,在他於1933年所寫的文章中誤用「人格分裂」一詞[219]。其他學者則追溯到更早的誤用根源[220]。

社會和文化

[編輯]

2002年,日本把這一種疾病的名稱由「精神分裂病 seishin-bunretsu-byō」改名為「統合失調症 tōgō-shitchō-shō」,以減少疾病名稱所帶來的社會污名[221],此一名字的靈感是來自生物-心理-社會模型的,且在實行三年內把接受診斷的人數從37%增加到70%[222]。2012年在韓國亦發生了類似的變化[223]。2014年,中華民國衛生福利部宣佈將「精神分裂症」正式更名為「思覺失調症」[29],此一名稱是考慮到此疾病的核心表現性質——「思考」及「知覺」[224]。精神病學教授吉姆·范·奧斯則建議把英語的「Schizophrenia」(思覺失調症)改名為「psychosis spectrum syndrome」(精神病類群障礙症)[225]。

在2002年的美國,思覺失調症的耗用成本估計為627億美元,當中計算了直接成本(門診、住院、藥物和長期護理)和非醫療保健成本(執法、生產率下降和失業)[226]。《美麗心靈》(「A Beautiful Mind」,另譯成《美麗境界》)是一部描寫約翰·福布斯·納什(John Forbes Nash Jr.)的生平電影以及書籍:他是一名罹患思覺失調症的諾貝爾經濟學獎得主[227]。有「中國的梵谷」之稱的沙耆亦同樣是思覺失調症患者,但他在發病之後仍在藜齋不停畫畫,其後他的畫作受畫壇賞識,在1980年代一幅畫作的價格更高達數萬人民幣[228]。

暴力

[編輯]患有嚴重精神疾病的人受到暴力或非暴力對待的風險會顯著增加,包括患有思覺失調症[229]。思覺失調症亦與較常使用暴力有關,但這主要是因為患者的吸毒率較高[230]。與精神病相關的兇殺率類似於與物質濫用相關的,且在一個地區內比例會差不多[231]。若把思覺失調症跟物質濫用分開看待後,其在使用暴力上扮演了什麽角色仍是具一定爭議性,但個人經歷或精神狀態的某些層面可能是使用暴力的其中一些因素[232]。約11%服刑中的兇殺者患有思覺失調症,21%的人則患有情緒障礙[233]。另一項研究發現,在研究進行的前一年內,約8-10%的思覺失調症患者對他人行使了暴力,而普通人口的比例則為2%[233]。

與患者行使暴力相關的報導加強了公眾認知中思覺失調症與暴力的聯繫[230]。一項在1999年進行的大型調查顯示,12.8%的美國人認為思覺失調症患者「很有可能」對他人行使暴力,48.1%的人則表示他們「有一點可能」會這樣做。超過74%的人說患者「不太能」或「不能全部地」作出與治療有關的決定,70.2%的人說金錢管理上的決定亦如是[234]。根據一項薈萃分析顯示,自1950年代以來,行使暴力的精神病患者已經上升了不止一倍[235]。

研究方向

[編輯]初步研究證實,米諾環素對患者病情的改善有一些效果[236]。亦有關於硝化療法及努力改善患者的生活環境的研究,用以改善他們能力上的缺陷;然而目前為止還沒有足夠的證據去對其有效性作出結論[237]。研究人員已證實負性症狀是會對治療産生挑戰,因為它們通常不能透過藥物治療改善。他們亦因此對各種藥劑進行了研究,以確定它們可能帶來的效果[238],並基於在病理學上,發炎可能對思覺失調症起了一定作用,所以已有針對擁有抗發炎活性的藥物的研究[239]。

參考文獻

[編輯]- ^ Jones, Daniel, Peter Roach, James Hartmann and Jane Setter , 編, English Pronouncing Dictionary, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003 [1917], ISBN 3-12-539683-2

- ^ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Schizophrenia Fact sheet N°397. WHO. 2015-09 [2016-02-03]. (原始內容存檔於2016-10-18).

- ^ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Schizophrenia. National Institute of Mental Health. 2016-01 [2016-02-03]. (原始內容存檔於2016-11-25).

- ^ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 4.8 Owen, MJ; Sawa, A; Mortensen, PB. Schizophrenia.. Lancet (London, England). 2016-01-14. PMID 26777917. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01121-6.

- ^ 5.0 5.1 Lachance LR, McKenzie K. Biomarkers of gluten sensitivity in patients with non-affective psychosis: a meta-analysis. Schizophr Res (Review). 2014-02, 152 (2–3): 521–7. PMID 24368154. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2013.12.001.

- ^ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 6.10 6.11 6.12 American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th. Arlington: American Psychiatric Publishing. : 101–105. ISBN 978-0890425558.

- ^ Ferri FF. Ferri's differential diagnosis : a practical guide to the differential diagnosis of symptoms, signs, and clinical disorders 2nd. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Mosby. 2010: Chapter S. ISBN 978-0-323-07699-9.

- ^ 8.0 8.1 Medicinal treatment of psychosis/schizophrenia. www.sbu.se. Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services. 2012-11-21 [2017-06-26]. (原始內容存檔於2017-06-29) (英語).

- ^ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 Laursen TM, Munk-Olsen T, Vestergaard M. Life expectancy and cardiovascular mortality in persons with schizophrenia. Current opinion in psychiatry. 2012-03, 25 (2): 83{{subst:一字線}}88. PMID 22249081. doi:10.1097/YCO.0b013e32835035ca.

- ^ 10.00 10.01 10.02 10.03 10.04 10.05 10.06 10.07 10.08 10.09 10.10 10.11 10.12 10.13 10.14 10.15 10.16 10.17 10.18 10.19 van Os J, Kapur S. Schizophrenia (PDF). Lancet. 2009-08, 374 (9690): 635{{subst:一字線}}645 [2016-10-17]. PMID 19700006. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60995-8. (原始內容 (PDF)存檔於2016-03-03).

- ^ 11.0 11.1 GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death, Collaborators. Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015.. Lancet (London, England). 2016-10-08, 388 (10053): 1459{{subst:一字線}}1544. PMID 27733281. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(16)31012-1.

- ^ 12.0 12.1 12.2 郝偉,陸林.精神病學 [M]. 8版.北京:人民衛生出版社, 2018: 85.

- ^ 13.0 13.1 精神分裂症 (頁面存檔備份,存於網際網路檔案館) [DB/OL] [2024] // 陳至立.辭海. 7版網絡版.上海:上海辭書出版社, 2020.

- ^ World Health Organization (WHO, 世界衛生組織). 06 Mental, behavioural or neurodevelopmental disorders (06 精神、行為或神經發展疾患)//ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics [DB/OL], 2024-01. Schizophrenia or other primary psychotic disorders 思覺失調症或其他原發性精神病性障礙 (頁面存檔備份,存於網際網路檔案館).

- ^ 第8章 思覺失調症譜系及其他精神病性障礙.王登峰,審校//NOLEN-HOEKSEMA S.變態心理學 [M].鄒丹,等,譯. 6版.人民郵電出版社, 2017: 241.

- ^ World Health Organization (WHO, 世界衛生組織). 06 Mental, behavioural or neurodevelopmental disorders (06 精神、行為或神經發展疾患)//ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics [DB/OL], 2024-01. 6A20 Schizophrenia 思覺失調症 (頁面存檔備份,存於網際網路檔案館).

- ^ Buckley PF; Miller BJ; Lehrer DS; Castle DJ. Psychiatric comorbidities and schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2009-03, 35 (2): 383–402. ISSN 0586-7614. PMC 2659306

. PMID 19011234. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbn135.

. PMID 19011234. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbn135.

- ^ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 Chadwick B; Miller ML; Hurd YL. Cannabis Use during Adolescent Development: Susceptibility to Psychiatric Illness. Front Psychiatry (Review). 2013, 4: 129. PMC 3796318

. PMID 24133461. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2013.00129.

. PMID 24133461. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2013.00129.

- ^ 19.0 19.1 Kavanagh, D H; Tansey, K E; O'Donovan, M C; Owen, M J. Schizophrenia genetics: emerging themes for a complex disorder. Molecular Psychiatry. 2014, 20 (1): 72–76. ISSN 1359-4184. doi:10.1038/mp.2014.148.

- ^ 20.00 20.01 20.02 20.03 20.04 20.05 20.06 20.07 20.08 20.09 20.10 20.11 20.12 Picchioni MM; Murray RM. Schizophrenia. BMJ. 2007-07, 335 (7610): 91{{subst:一字線}}95. PMC 1914490

. PMID 17626963. doi:10.1136/bmj.39227.616447.BE.

. PMID 17626963. doi:10.1136/bmj.39227.616447.BE.

- ^ 21.0 21.1 Kane JM; Correll CU. Pharmacologic treatment of schizophrenia. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2010, 12 (3): 345–57. PMC 3085113

. PMID 20954430.

. PMID 20954430.

- ^ 22.0 22.1 Becker T; Kilian R. Psychiatric services for people with severe mental illness across western Europe: what can be generalized from current knowledge about differences in provision, costs and outcomes of mental health care?. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica Supplement. 2006, 113 (429): 9{{subst:一字線}}16. PMID 16445476. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00711.x.

- ^ 23.0 23.1 Schizophrenia. World Health Organization. 2019 [2020-12-23]. (原始內容存檔於2016-11-08).

- ^ 24.0 24.1 Lawrence RE, First MB, Lieberman JA. Chapter 48: Schizophrenia and Other Psychoses. Tasman A, Kay J, Lieberman JA, First MB, Riba MB (編). Psychiatry fourth. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. 2015: 798, 816, 819. ISBN 978-1-118-84547-9. doi:10.1002/9781118753378.ch48.

- ^ Foster, A; Gable, J; Buckley, J. Homelessness in schizophrenia.. The Psychiatric clinics of North America. 2012-09, 35 (3): 717–34. PMID 22929875. doi:10.1016/j.psc.2012.06.010.

- ^ 26.0 26.1 Hor K; Taylor M. Suicide and schizophrenia: a systematic review of rates and risk factors. Journal of psychopharmacology (Oxford, England). 2010-11, 24 (4 Suppl): 81–90. PMID 20923923. doi:10.1177/1359786810385490.

- ^ schizophrenia // 牛津大學出版社,上海外語教育出版社.新牛津英漢雙解大詞典 [DB]. 2版.上海:上海外語教育出版社, 2012.

- ^ 28.0 28.1 黃敏偉. Schizophrenia中文診斷名稱意見調查說明 (PDF). 台灣精神醫學會. [2016-11-18]. (原始內容 (PDF)存檔於2013-11-26).

- ^ 29.0 29.1 29.2 您知道嗎?「精神分裂症」已經更名為「思覺失調症」. 中華民國衛生福利部. 2014-06-24 [2016-11-30]. (原始內容存檔於2016-08-17).

- ^ 您知道嗎?「精神分裂症」已經更名為「思覺失調症」. 心理及口腔健康司. 衛生福利部. 2014-06-24. (原始內容存檔於2022-07-02).

- ^ Schizophrenia中文譯名由「精神分裂症」更名為「思覺失調症」的歷史軌跡. 台灣精神醫學會. 2014-05-30. (原始內容存檔於2021-05-10).

- ^ 思觉失调 (PDF).

- ^ 照護線上. 「思覺失調」八大迷思:得了這種病會有多重人格嗎?. The News Lens 關鍵評論網. 2019-05-17 [2024-04-17]. (原始內容存檔於2024-04-17) (中文(臺灣)).

- ^ 中華人民共和國國家衛生健康委員會.精神障礙診療規範 [S/OL]. 2020年版: 115-125. 原始文件 (頁面存檔備份,存於網際網路檔案館).

- ^ 35.0 35.1 35.2 Carson VB. Mental Health Nursing: The Nurse-patient Journey. W.B. Saunders. 2000: 638. ISBN 978-0-7216-8053-8. (原始內容存檔於2016-05-13) (英語).

- ^ 36.0 36.1 36.2 Heinz A, Voss M, Lawrie SM, Mishara A, Bauer M, Gallinat J, et al. Shall we really say goodbye to first rank symptoms?. European Psychiatry. September 2016, 37: 8–13. PMID 27429167. doi:10.1016/j.eurpsy.2016.04.010.

- ^ Hirsch SR, Weinberger DR. Schizophrenia. Wiley-Blackwell. 2003: 21. ISBN 978-0-632-06388-8. (原始內容存檔於2015-03-20).

- ^ Brunet-Gouet E, Decety J. Social brain dysfunctions in schizophrenia: a review of neuroimaging studies. Psychiatry Research. December 2006, 148 (2–3): 75–92. PMID 17088049. doi:10.1016/j.pscychresns.2006.05.001.

- ^ Ungvari GS; Caroff SN; Gerevich J. The catatonia conundrum: evidence of psychomotor phenomena as a symptom dimension in psychotic disorders. Schizophr Bull. 2010-03, 36 (2): 231–8. PMC 2833122

. PMID 19776208. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbp105.

. PMID 19776208. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbp105.

- ^ Kohler CG; Walker JB; Martin EA; Healey KM; Moberg PJ. Facial emotion perception in schizophrenia: a meta-analytic review. Schizophr Bull. 2010-09, 36 (5): 1009–19. PMC 2930336

. PMID 19329561. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbn192. (原始內容存檔於2015-07-25).

. PMID 19329561. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbn192. (原始內容存檔於2015-07-25).

- ^ Current diagnosis & treatment psychiatry 2nd. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. 2008: 48. ISBN 978-0-07-142292-5.

- ^ Oyebode F. Sims' Symptoms in the Mind E-Book: Textbook of Descriptive Psychopathology. Elsevier Health Sciences. 2014: 152. ISBN 978-0-7020-5555-3 (英語).

- ^ Baier M. Insight in schizophrenia: a review. Current psychiatry reports. 2010-08, 12 (4): 356–61. PMID 20526897. doi:10.1007/s11920-010-0125-7.

- ^ Pijnenborg GH; van Donkersgoed RJ; David AS; Aleman A. Changes in insight during treatment for psychotic disorders: a meta-analysis. Schizophrenia Research. 2013-03, 144 (1–3): 109–17. PMID 23305612. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2012.11.018.

- ^ Fadgyas-Stanculete, M; Buga, AM; Popa-Wagner, A; Dumitrascu, DL. The relationship between irritable bowel syndrome and psychiatric disorders: from molecular changes to clinical manifestations.. Journal of molecular psychiatry. 2014, 2 (1): 4. PMID 25408914. doi:10.1186/2049-9256-2-4.

- ^ Goroll AH, Mulley AG. Primary Care Medicine: Office Evaluation and Management of The Adult Patient: Sixth Edition. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2011: Chapter 101. ISBN 978-1-4511-2159-9 (英語).

- ^ Sims A. Symptoms in the mind: an introduction to descriptive psychopathology. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders. 2002. ISBN 0-7020-2627-1.

- ^ Kneisl C. and Trigoboff E. (2009). Contemporary Psychiatric- Mental Health Nursing. 2nd edition. London: Pearson Prentice Ltd. p. 371

- ^ 49.0 49.1 American Psychiatric Association. Task Force on DSM-IV. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV-TR. American Psychiatric Pub. ISBN 978-0-89042-025-6. p. 299

- ^ Velligan DI & Alphs LD. Negative Symptoms in Schizophrenia: The Importance of Identification and Treatment. Psychiatric Times. 2008-03-01, 25 (3). (原始內容存檔於2009-10-06).

- ^ 51.0 51.1 51.2 51.3 Smith T; Weston C; Lieberman J. Schizophrenia (maintenance treatment). Am Fam Physician. 2010-08, 82 (4): 338–9. PMID 20704164.

- ^ Buxbaum J, Sklar P, Nestler E, Charney D. 17. Neurobiology of Mental Illness 4th. Oxford University Press. 2013. ISBN 978-0-19-993495-9.

- ^ 53.0 53.1 53.2 53.3 53.4 Bozikas VP, Andreou C. Longitudinal studies of cognition in first episode psychosis: a systematic review of the literature. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. February 2011, 45 (2): 93–108. PMID 21320033. doi:10.3109/00048674.2010.541418. (原始內容存檔於2016-11-30).

- ^ Dauvermann MR, Whalley HC, Schmidt A, Lee GL, Romaniuk L, Roberts N, Johnstone EC, Lawrie SM, Moorhead TW. Computational neuropsychiatry - schizophrenia as a cognitive brain network disorder. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2014-01-01, 5: 30. PMC 3971172

. PMID 24723894. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2014.00030. (原始內容存檔於2016-03-19).

. PMID 24723894. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2014.00030. (原始內容存檔於2016-03-19).

- ^ 55.0 55.1 Shah JN, Qureshi SU, Jawaid A, Schulz PE. Is there evidence for late cognitive decline in chronic schizophrenia?. The Psychiatric Quarterly. June 2012, 83 (2): 127–44. PMID 21863346. doi:10.1007/s11126-011-9189-8.

- ^ 56.0 56.1 56.2 Goldberg TE, Keefe RS, Goldman RS, Robinson DG, Harvey PD. Circumstances under which practice does not make perfect: a review of the practice effect literature in schizophrenia and its relevance to clinical treatment studies. Neuropsychopharmacology. April 2010, 35 (5): 1053–62. PMC 3055399

. PMID 20090669. doi:10.1038/npp.2009.211. (原始內容存檔於2016-02-07).

. PMID 20090669. doi:10.1038/npp.2009.211. (原始內容存檔於2016-02-07).

- ^ 57.00 57.01 57.02 57.03 57.04 57.05 57.06 57.07 57.08 57.09 Kurtz MM, Moberg PJ, Gur RC, Gur RE. Approaches to cognitive remediation of neuropsychological deficits in schizophrenia: a review and meta-analysis. Neuropsychology Review. December 2001, 11 (4): 197–210 [2018-07-30]. PMID 11883669. doi:10.1023/A:1012953108158. (原始內容存檔於2018-07-13).

- ^ 58.0 58.1 Tan BL. Profile of cognitive problems in schizophrenia and implications for vocational functioning. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal. August 2009, 56 (4): 220–8. PMID 20854522. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1630.2008.00759.x. (原始內容存檔於2016-11-13).

- ^ Cirillo MA, Seidman LJ. Verbal declarative memory dysfunction in schizophrenia: from clinical assessment to genetics and brain mechanisms. Neuropsychology Review. June 2003, 13 (2): 43–77. PMID 12887039. doi:10.1023/A:1023870821631.

- ^ Pomarol-Clotet E, Oh TM, Laws KR, McKenna PJ. Semantic priming in schizophrenia: systematic review and meta-analysis. The British Journal of Psychiatry. February 2008, 192 (2): 92–7. PMID 18245021. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.106.032102. (原始內容存檔於2016-05-25).

- ^ 61.0 61.1 Barch DM. Cognition in Schizophrenia Does Working Memory Work?. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2003-08-01, 12 (4): 146–150. ISSN 0963-7214. doi:10.1111/1467-8721.01251. (原始內容存檔於2016-11-30).

- ^ 62.0 62.1 Addington J, Cadenhead KS, Cannon TD, Cornblatt B, McGlashan TH, Perkins DO, Seidman LJ, Tsuang M, Walker EF, Woods SW, Heinssen R. North American Prodrome Longitudinal Study: a collaborative multisite approach to prodromal schizophrenia research. Schizophrenia Bulletin. May 2007, 33 (3): 665–72. PMC 2526151

. PMID 17255119. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbl075.

. PMID 17255119. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbl075.

- ^ Cullen KR, Kumra S, Regan J, et al. Atypical Antipsychotics for Treatment of Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders. Psychiatric Times. 2008, 25 (3). (原始內容存檔於2008-12-28).

- ^ Ochoa S, Usall J, Cobo J, Labad X, Kulkarni J. Gender differences in schizophrenia and first-episode psychosis: a comprehensive literature review. Schizophrenia Research and Treatment (Review). 2012, 2012: 916198. PMC 3420456

. PMID 22966451. doi:10.1155/2012/916198.

. PMID 22966451. doi:10.1155/2012/916198.

- ^ Amminger GP, Leicester S, Yung AR, et al. Early onset of symptoms predicts conversion to non-affective psychosis in ultra-high risk individuals. Schizophrenia Research. 2006, 84 (1): 67–76. PMID 16677803. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2006.02.018.

- ^ Coyle, Joseph. Chapter 54: The Neurochemistry of Schizophrenia. Siegal, George J; et al (編). Basic Neurochemistry: Molecular, Cellular and Medical Aspects 7th. Burlington, MA: Elsevier Academic Press. 2006: 876–78. ISBN 0-12-088397-X.

- ^ Parnas J, Jorgensen A. Pre-morbid psychopathology in schizophrenia spectrum. The British Journal of Psychiatry. November 1989, 155 (5): 623–7. PMID 2611591. doi:10.1192/s0007125000018109.

- ^ Khandaker GM, Barnett JH, White IR, Jones PB. A quantitative meta-analysis of population-based studies of premorbid intelligence and schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. November 2011, 132 (2–3): 220–7. PMC 3485562

. PMID 21764562. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2011.06.017.

. PMID 21764562. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2011.06.017.

- ^ Welham J, Isohanni M, Jones P, McGrath J. The antecedents of schizophrenia: a review of birth cohort studies. Schizophrenia Bulletin. May 2009, 35 (3): 603–23. PMC 2669575

. PMID 18658128. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbn084.

. PMID 18658128. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbn084.

- ^ Dickson H, Laurens KR, Cullen AE, Hodgins S. Meta-analyses of cognitive and motor function in youth aged 16 years and younger who subsequently develop schizophrenia. Psychological Medicine. April 2012, 42 (4): 743–55. PMID 21896236. doi:10.1017/s0033291711001693. (原始內容存檔於2017-02-02).

- ^ 劉恩山.普通高中教科書·生物學:必修2:遺傳與演化 [M/OL].朱立祥,李曉輝,副主編.杭州:浙江科學技術出版社, 2019: 109 (2022-12) [2024]. 國家中小學智慧教育平台[失效連結].

- ^ 中華人民共和國國家衛生健康委員會.精神障礙診療規範 (頁面存檔備份,存於網際網路檔案館) [S/OL]. 2020年版: 116-117.

- ^ 73.0 73.1 Herson M. Etiological considerations. Adult psychopathology and diagnosis. John Wiley & Sons. 2011 [2016-10-24]. ISBN 9781118138847. (原始內容存檔於2016-11-24).

- ^ O'Donovan MC; Williams NM; Owen MJ. Recent advances in the genetics of schizophrenia. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2003-10,. 12 Spec No 2: R125–33. PMID 12952866. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddg302.

- ^ Drake RJ; Lewis SW. Early detection of schizophrenia. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2005-03, 18 (2): 147–50. PMID 16639167. doi:10.1097/00001504-200503000-00007.

- ^ Farrell MS, Werge T, Sklar P, Owen MJ, Ophoff RA, O'Donovan MC, Corvin A, Cichon S, Sullivan PF. Evaluating historical candidate genes for schizophrenia. Molecular Psychiatry. 2015, 20 (5): 555–62. PMC 4414705

. PMID 25754081. doi:10.1038/mp.2015.16.

. PMID 25754081. doi:10.1038/mp.2015.16.

- ^ Schork AJ, Wang Y, Thompson WK, Dale AM, Andreassen OA. New statistical approaches exploit the polygenic architecture of schizophrenia--implications for the underlying neurobiology. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. February 2016, 36: 89–98. PMC 5380793

. PMID 26555806. doi:10.1016/j.conb.2015.10.008.

. PMID 26555806. doi:10.1016/j.conb.2015.10.008.

- ^ Kendler KS. The Schizophrenia Polygenic Risk Score: To What Does It Predispose in Adolescence?. JAMA Psychiatry. March 2016, 73 (3): 193–4. PMID 26817666. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.2964.

- ^ 79.0 79.1 Lowther C, Costain G, Baribeau DA, Bassett AS. Genomic Disorders in Psychiatry-What Does the Clinician Need to Know?. Current Psychiatry Reports. September 2017, 19 (11): 82. PMID 28929285. doi:10.1007/s11920-017-0831-5.

- ^ The Brainstorm Consortium; Anttila, Verneri; Bulik-Sullivan, Brendan; Finucane, Hilary K; et al. Analysis of shared heritability in common disorders of the brain. Science. 2018-06-22, 360 (6395) [2018-07-28]. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 29930110. doi:10.1126/science.aap8757. (原始內容存檔於2018-07-03).

- ^ 張夢然.神經與精神疾病單細胞水平研究結果重磅發布 [N/OL].科技日報, 2024-05-27 (4). http://digitalpaper.stdaily.com/http_www.kjrb.com/kjrb/images/2024-05/27/04/KJRB2024052704.pdf (頁面存檔備份,存於網際網路檔案館).

- ^ Negrón-Oyarzo I, Lara-Vásquez A, Palacios-García I, Fuentealba P, Aboitiz F. Schizophrenia and reelin: a model based on prenatal stress to study epigenetics, brain development and behavior. Biological Research. 2016, 49: 16. PMC 4787713

. PMID 26968981. doi:10.1186/s40659-016-0076-5.

. PMID 26968981. doi:10.1186/s40659-016-0076-5.

- ^ 83.0 83.1 Brown AS. The environment and susceptibility to schizophrenia. Progress in Neurobiology. 2011, 93 (1): 23–58. PMC 3521525

. PMID 20955757. doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2010.09.003.

. PMID 20955757. doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2010.09.003.

- ^ le Charpentier Y, Hoang C, Mokni M, Finet JF, Biaggi A, Saguin M, Plantier F. [Histopathology and ultrastructure of opportunistic infections of the digestive tract in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome]. Archives d'Anatomie et De Cytologie Pathologiques. 2005, 40 (2–3): 138–49. PMC 1280409

. PMID 16140635. doi:10.1289/ehp.7572.

. PMID 16140635. doi:10.1289/ehp.7572.

- ^ Dvir Y; Denietolis B; Frazier JA. Childhood trauma and psychosis. Child and adolescent psychiatric clinics of North America. 2013-10, 22 (4): 629–41. PMID 24012077. doi:10.1016/j.chc.2013.04.006.

- ^ Misiak B, Krefft M, Bielawski T, Moustafa AA, Sąsiadek MM, Frydecka D. Toward a unified theory of childhood trauma and psychosis: A comprehensive review of epidemiological, clinical, neuropsychological and biological findings. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2017, 75: 393–406. PMID 28216171. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.02.015.

- ^ Van Os J. Does the urban environment cause psychosis?. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2004, 184 (4): 287–288. PMID 15056569. doi:10.1192/bjp.184.4.287.

- ^ Selten JP; Cantor-Graae E; Kahn RS. Migration and schizophrenia. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2007-03, 20 (2): 111–115. PMID 17278906. doi:10.1097/YCO.0b013e328017f68e.

- ^ Nemani, K; Hosseini Ghomi, R; McCormick, B; Fan, X. Schizophrenia and the gut-brain axis.. Progress in neuro-psychopharmacology & biological psychiatry. 2015-01-02, 56: 155–60. PMID 25240858. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2014.08.018.

- ^ 90.0 90.1 90.2 Gregg L; Barrowclough C; Haddock G. Reasons for increased substance use in psychosis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2007, 27 (4): 494–510. PMID 17240501. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2006.09.004.

- ^ Larson M. Alcohol-Related Psychosis. EMedicine. 2006-03-30 [2006-09-27]. (原始內容存檔於2008-11-09).

- ^ Sagud M, Mihaljević-Peles A, Mück-Seler D, et al. Smoking and schizophrenia (PDF). Psychiatr Danub. 2009-09, 21 (3): 371–5. PMID 19794359. (原始內容存檔 (PDF)於2016-03-04).

- ^ Alcohol-Related Psychosis 於 eMedicine

- ^ Large M; Sharma S; Compton MT; Slade T; Nielssen O. Cannabis use and earlier onset of psychosis: a systematic meta-analysis. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2011-06, 68 (6): 555–61. PMID 21300939. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.5.

- ^ 95.0 95.1 95.2 Niesink RJ; van Laar MW. Does cannabidiol protect against adverse psychological effects of THC?. Frontiers in Psychiatry (Review). 2013, 4: 130. PMC 3797438

. PMID 24137134. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2013.00130.

. PMID 24137134. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2013.00130.

- ^ 96.0 96.1 96.2 Parakh P; Basu D. Cannabis and psychosis: have we found the missing links?. Asian Journal of Psychiatry (Review). 2013-08, 6 (4): 281–7. PMID 23810133. doi:10.1016/j.ajp.2013.03.012.

Cannabis acts as a component cause of psychosis, that is, it increases the risk of psychosis in people with certain genetic or environmental vulnerabilities, though by itself, it is neither a sufficient nor a necessary cause of psychosis.

- ^ Gage, SH; Hickman, M; Zammit, S. Association Between Cannabis and Psychosis: Epidemiologic Evidence.. Biological Psychiatry. 2015-08-12. PMID 26386480. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.08.001.

- ^ Leweke FM; Koethe D. Cannabis and psychiatric disorders: it is not only addiction. Addict Biol. 2008-06, 13 (2): 264–75. PMID 18482435. doi:10.1111/j.1369-1600.2008.00106.x.

- ^ Yolken R. Viruses and schizophrenia: a focus on herpes simplex virus. Herpes. 2004-06, 11 (Suppl 2): 83A–88A. PMID 15319094.

- ^ Arias, I; Sorlozano, A; Villegas, E; de Dios Luna, J; McKenney, K; Cervilla, J; Gutierrez, B; Gutierrez, J. Infectious agents associated with schizophrenia: a meta-analysis.. Schizophrenia Research. 2012-04, 136 (1-3): 128–36. PMID 22104141. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2011.10.026.

- ^ Insel TR. Rethinking schizophrenia. Nature. 2010, 468 (7321): 187–93. Bibcode:2010Natur.468..187I. PMID 21068826. doi:10.1038/nature09552.

- ^ Fusar-Poli P, Meyer-Lindenberg A. Striatal presynaptic dopamine in schizophrenia, part II: meta-analysis of [(18)F/(11)C]-DOPA PET studies. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2013, 39 (1): 33–42. PMC 3523905

. PMID 22282454. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbr180.

. PMID 22282454. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbr180.

- ^ Howes OD, Kambeitz J, Kim E, Stahl D, Slifstein M, Abi-Dargham A, Kapur S. The nature of dopamine dysfunction in schizophrenia and what this means for treatment. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2012, 69 (8): 776–86. PMC 3730746

. PMID 22474070. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2012.169.

. PMID 22474070. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2012.169.

- ^ Broyd A, Balzan RP, Woodward TS, Allen P. Dopamine, cognitive biases and assessment of certainty: A neurocognitive model of delusions. Clinical Psychology Review. 2017, 54: 96–106. PMID 28448827. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2017.04.006.

- ^ Howes OD, Murray RM. Schizophrenia: an integrated sociodevelopmental-cognitive model. Lancet. 2014, 383 (9929): 1677–1687. PMC 4127444

. PMID 24315522. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62036-X.

. PMID 24315522. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62036-X.

- ^ Grace AA. Dysregulation of the dopamine system in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia and depression. Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 2016, 17 (8): 524–32. PMC 5166560

. PMID 27256556. doi:10.1038/nrn.2016.57.

. PMID 27256556. doi:10.1038/nrn.2016.57.

- ^ Goldman-Rakic PS, Castner SA, Svensson TH, Siever LJ, Williams GV. Targeting the dopamine D1 receptor in schizophrenia: insights for cognitive dysfunction. Psychopharmacology. 2004, 174 (1): 3–16. PMID 15118803. doi:10.1007/s00213-004-1793-y.

- ^ Arnsten AF, Girgis RR, Gray DL, Mailman RB. Novel Dopamine Therapeutics for Cognitive Deficits in Schizophrenia. Biological Psychiatry. 2017, 81 (1): 67–77. PMC 4949134

. PMID 26946382. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.12.028.

. PMID 26946382. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.12.028.

- ^ Abi-Dargham A, Moore H. Prefrontal DA transmission at D1 receptors and the pathology of schizophrenia. The Neuroscientist. October 2003, 9 (5): 404–16. PMID 14580124. doi:10.1177/1073858403252674.

- ^ Maia TV, Frank MJ. An Integrative Perspective on the Role of Dopamine in Schizophrenia. Biological Psychiatry. 2017, 81 (1): 52–66. PMC 5486232

. PMID 27452791. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2016.05.021.

. PMID 27452791. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2016.05.021.

- ^ Catts VS, Lai YL, Weickert CS, Weickert TW, Catts SV. A quantitative review of the post-mortem evidence for decreased cortical N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor expression levels in schizophrenia: How can we link molecular abnormalities to mismatch negativity deficits?. Biological Psychology. 2016, 116: 57–67. PMID 26549579. doi:10.1016/j.biopsycho.2015.10.013.

- ^ Michie PT, Malmierca MS, Harms L, Todd J. The neurobiology of MMN and implications for schizophrenia. Biological Psychology. 2016, 116: 90–7. PMID 26826620. doi:10.1016/j.biopsycho.2016.01.011.

- ^ Pratt J, Dawson N, Morris BJ, Grent-'t-Jong T, Roux F, Uhlhaas PJ. Thalamo-cortical communication, glutamatergic neurotransmission and neural oscillations: A unique window into the origins of ScZ?. Schizophrenia Research. 2017, 180: 4–12. PMID 27317361. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2016.05.013.

- ^ 114.0 114.1 Marín O. Interneuron dysfunction in psychiatric disorders. Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. January 2012, 13 (2): 107–20. PMID 22251963. doi:10.1038/nrn3155.

- ^ Lewis DA, Hashimoto T, Volk DW. Cortical inhibitory neurons and schizophrenia. Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 2005, 6 (4): 312–24. PMID 15803162. doi:10.1038/nrn1648.

- ^ Senkowski D, Gallinat J. Dysfunctional prefrontal gamma-band oscillations reflect working memory and other cognitive deficits in schizophrenia. Biological Psychiatry. 2015, 77 (12): 1010–9. PMID 25847179. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.02.034.

Several studies that investigated perceptual processes found impaired GBR in ScZ patients over sensory areas, such as the auditory and visual cortex. Moreover, studies examining steady-state auditory-evoked potentials showed deficits in the gen- eration of oscillations in the gamma band.

- ^ Reilly TJ, Nottage JF, Studerus E, Rutigliano G, Micheli AI, Fusar-Poli P, McGuire P. Gamma band oscillations in the early phase of psychosis: A systematic review. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2018, 90: 381–399. PMID 29656029. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.04.006.

Decreased gamma power in response to a task was a relatively consistent finding, with 5 out of 6 studies reported reduced evoked or induced power.

- ^ Birnbaum R, Weinberger DR. Genetic insights into the neurodevelopmental origins of schizophrenia. Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 2017, 18 (12): 727–740. PMID 29070826. doi:10.1038/nrn.2017.125.

- ^ Khandaker GM, Zimbron J, Lewis G, Jones PB. Prenatal maternal infection, neurodevelopment and adult schizophrenia: a systematic review of population-based studies. Psychological Medicine. February 2013, 43 (2): 239–57. PMC 3479084

. PMID 22717193. doi:10.1017/S0033291712000736.

. PMID 22717193. doi:10.1017/S0033291712000736.

- ^ Brown AS, Derkits EJ. Prenatal infection and schizophrenia: a review of epidemiologic and translational studies. The American Journal of Psychiatry. March 2010, 167 (3): 261–80. PMC 3652286

. PMID 20123911. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09030361.

. PMID 20123911. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09030361.

- ^ Cannon TD. How Schizophrenia Develops: Cognitive and Brain Mechanisms Underlying Onset of Psychosis. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2015, 19 (12): 744–756. PMC 4673025

. PMID 26493362. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2015.09.009.

. PMID 26493362. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2015.09.009.

- ^ Lesh TA, Niendam TA, Minzenberg MJ, Carter CS. Cognitive control deficits in schizophrenia: mechanisms and meaning. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011, 36 (1): 316–38. PMC 3052853

. PMID 20844478. doi:10.1038/npp.2010.156.

. PMID 20844478. doi:10.1038/npp.2010.156.

- ^ Barch DM, Ceaser A. Cognition in schizophrenia: core psychological and neural mechanisms. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2012, 16 (1): 27–34. PMC 3860986

. PMID 22169777. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2011.11.015.

. PMID 22169777. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2011.11.015.

- ^ Eisenberg DP, Berman KF. Executive function, neural circuitry, and genetic mechanisms in schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010, 35 (1): 258–77. PMC 2794926

. PMID 19693005. doi:10.1038/npp.2009.111.

. PMID 19693005. doi:10.1038/npp.2009.111.

- ^ Walton E, Hibar DP, van Erp TG, Potkin SG, Roiz-Santiañez R, Crespo-Facorro B, et al. Positive symptoms associate with cortical thinning in the superior temporal gyrus via the ENIGMA Schizophrenia consortium. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2017, 135 (5): 439–447. PMC 5399182

. PMID 28369804. doi:10.1111/acps.12718.

. PMID 28369804. doi:10.1111/acps.12718.

- ^ Walton E, Hibar DP, van Erp TG, Potkin SG, Roiz-Santiañez R, Crespo-Facorro B, et al. Prefrontal cortical thinning links to negative symptoms in schizophrenia via the ENIGMA consortium. Psychological Medicine. 2018, 48 (1): 82–94. PMC 5826665

. PMID 28545597. doi:10.1017/S0033291717001283.

. PMID 28545597. doi:10.1017/S0033291717001283.

- ^ Cohen AS, Minor KS. Emotional experience in patients with schizophrenia revisited: meta-analysis of laboratory studies. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2010, 36 (1): 143–50. PMC 2800132

. PMID 18562345. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbn061.

. PMID 18562345. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbn061.

- ^ Strauss GP, Gold JM. A new perspective on anhedonia in schizophrenia. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2012, 169 (4): 364–73. PMC 3732829

. PMID 22407079. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11030447.

. PMID 22407079. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11030447.

- ^ Young J, Anticevic A, Barch D. Cognitive and Motivational Neuroscience of Psychotic Disorders. Charney D, Buxbaum J, Sklar P, Nestler E (編). Charney & Nestler's Neurobiology of Mental Illness 5th. New York: Oxford University Press. 2018: 215, 217. ISBN 9780190681425.

Several recent reviews (e.g., Cohen and Minor, 2010) have found that individuals with schizophrenia show relatively intact self-reported emotional responses to affect-eliciting stimuli as well as other indicators of intact response(215)...Taken together, the literature increasingly suggests that there may be a deficit in putatively DA-mediated reward learning and/ or reward prediction functions in schizophrenia. Such findings suggest that impairment in striatal reward prediction mechanisms may influence 「wanting」 in schizophrenia in a way that reduces the ability of individuals with schizophrenia to use anticipated rewards to drive motivated behavior.(217)

- ^ 130.0 130.1 130.2 American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th. Arlington: American Psychiatric Publishing. 1999. ISBN 978-0890425558.

- ^ 131.0 131.1 131.2 131.3 Tandon R, Gaebel W, Barch DM, et al. Definition and description of schizophrenia in the DSM-5. Schizophr. Res. 2013-10, 150 (1): 3–10. PMID 23800613. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2013.05.028.

- ^ As referenced from PMID 23800613, Heckers S; Tandon R; Bustillo J. Catatonia in the DSM--shall we move or not?. Schizophr Bull (Editorial). 2010-03, 36 (2): 205–7. PMC 2833126

. PMID 19933711. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbp136.

. PMID 19933711. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbp136.

- ^ Barch DM, Bustillo J, Gaebel W, et al. Logic and justification for dimensional assessment of symptoms and related clinical phenomena in psychosis: relevance to DSM-5. Schizophr. Res. 2013-10, 150 (1): 15–20. PMID 23706415. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2013.04.027.

- ^ Jakobsen KD, Frederiksen JN, Hansen T, et al. Reliability of clinical ICD-10 schizophrenia diagnoses. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry. 2005, 59 (3): 209–12. PMID 16195122. doi:10.1080/08039480510027698.

- ^ American Psychiatric Association DSM-5 Work Groups (2010) Proposed Revisions – Schizophrenia and Other Psychotic Disorders (頁面存檔備份,存於網際網路檔案館). Retrieved 17 February 2010.

- ^ 136.0 136.1 The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders (PDF). World Health Organization: 26. (原始內容存檔 (PDF)於2016-06-18).

- ^ DSM-5 Changes: Schizophrenia & Psychotic Disorders. 2014-05-29 [2016-01-08]. (原始內容存檔於2016-05-01).

- ^ МКБ-10: Классификация психических и поведенческих расстройств. F21 Шизотипическое расстройство [The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders. F21 Schizotypal Disorder] [archived 2016-04-22]. Russian.

- ^ Pope HG. Distinguishing bipolar disorder from schizophrenia in clinical practice: guidelines and case reports. Hospital and Community Psychiatry. 1983, 34: 322–28. PMID 6840720. doi:10.1176/ps.34.4.322.

- ^ McGlashan TH. Testing DSM-III symptom criteria for schizotypal and borderline personality disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1987-02, 44 (2): 143–8. PMID 3813809. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800140045007.

- ^ Bottas A. Comorbidity: Schizophrenia With Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Psychiatric Times. 2009-04-15, 26 (4). (原始內容存檔於2013-04-03).

- ^ Gabbard GO. Gabbard's Treatments of Psychiatric Disorders, Fourth Edition (Treatments of Psychiatric Disorders). American Psychiatric Publishing. 2007-05-15: 209–11. ISBN 1-58562-216-8.

- ^ Murray ED; Buttner N; Price BH. Depression and Psychosis in Neurological Practice. Bradley WG; Daroff RB; Fenichel GM; Jankovic J (編). Bradley's neurology in clinical practice 1 6th. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders. 2012: 92–111. ISBN 1-4377-0434-4.

- ^ Cannon TD; Cornblatt B; McGorry P. The empirical status of the ultra high-risk (prodromal) research paradigm. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2007-05, 33 (3): 661–4. PMC 2526144

. PMID 17470445. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbm031.

. PMID 17470445. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbm031.

- ^ Marshall M; Rathbone J. Early intervention for psychosis. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2011-06-15, (6): CD004718. PMC 4163966

. PMID 21678345. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004718.pub3.

. PMID 21678345. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004718.pub3.

- ^ de Koning MB, Bloemen OJ, van Amelsvoort TA, et al. Early intervention in patients at ultra high risk of psychosis: benefits and risks. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2009-06, 119 (6): 426–42. PMID 19392813. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2009.01372.x.

- ^ Stafford MR; Jackson H; Mayo-Wilson E; Morrison AP; Kendall T. Early interventions to prevent psychosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 2013-01-18, 346: f185. PMC 3548617

. PMID 23335473. doi:10.1136/bmj.f185.

. PMID 23335473. doi:10.1136/bmj.f185.

- ^ Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: treatment and management (PDF). NICE: 7. 2014-03 [2014-04-19]. (原始內容 (PDF)存檔於2014-04-20).

- ^ McGurk SR; Mueser KT; Feldman K; Wolfe R; Pascaris A. Cognitive training for supported employment: 2–3 year outcomes of a randomized controlled trial.. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007-03, 164 (3): 437–41 [2016-11-15]. PMID 17329468. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.164.3.437. (原始內容存檔於2007-03-03).

- ^ Gorczynski P; Faulkner G. Exercise therapy for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2010, (5): CD004412. PMID 20464730. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004412.pub2.

- ^ Dougall, N; Maayan, N; Soares-Weiser, K; McDermott, LM; McIntosh, A. Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) for schizophrenia.. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015-08-20, (8): CD006081. PMID 26289586. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006081.pub2.

- ^ 中華人民共和國國家衛生健康委員會.嚴重精神障礙管理治療工作規範 (頁面存檔備份,存於網際網路檔案館) [S]. 2018版.

- ^ 153.0 153.1 National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health. Schizophrenia: Full national clinical guideline on core interventions in primary and secondary care (PDF). 2009-03-25 [2009-11-25]. (原始內容 (PDF)存檔於2013-05-12).

- ^ Tandon R; Keshavan MS; Nasrallah HA. Schizophrenia, "Just the Facts": what we know in 2008 part 1: overview (PDF). Schizophrenia Research. 2008-03, 100 (1–3): 4–19. PMID 18291627. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2008.01.022.

- ^ 155.0 155.1 Leucht S, Tardy M, Komossa K, et al. Antipsychotic drugs versus placebo for relapse prevention in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2012-06, 379 (9831): 2063–71. PMID 22560607. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60239-6.

- ^ 156.0 156.1 156.2 Harrow M; Jobe TH. Does long-term treatment of schizophrenia with antipsychotic medications facilitate recovery?. Schizophrenia bulletin. 2013-03-19, 39 (5): 962–5. PMC 3756791

. PMID 23512950. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbt034.

. PMID 23512950. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbt034.

- ^ Seeman MV, Seeman P. Is schizophrenia a dopamine supersensitivity psychotic reaction?. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry. January 2014, 48: 155–60. PMC 3858317

. PMID 24128684. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2013.10.003.

. PMID 24128684. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2013.10.003.

- ^ Hartling L, Abou-Setta AM, Dursun S, et al. Antipsychotics in Adults With Schizophrenia: Comparative Effectiveness of First-generation versus second-generation medications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2012-08-14, 157 (7): 498–511. PMID 22893011. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-157-7-201210020-00525.

- ^ 159.0 159.1 159.2 Barry SJE; Gaughan TM; Hunter R. Schizophrenia. BMJ Clinical Evidence. 2012, 2012. PMC 3385413

. PMID 23870705. (原始內容存檔於2014-09-11).

. PMID 23870705. (原始內容存檔於2014-09-11).

- ^ Schultz SH; North SW; Shields CG. Schizophrenia: a review. Am Fam Physician. 2007-06, 75 (12): 1821–9. PMID 17619525.

- ^ Taylor DM. Refractory schizophrenia and atypical antipsychotics. J Psychopharmacol. 2000, 14 (4): 409–418. PMID 11198061. doi:10.1177/026988110001400411.

- ^ Essali A; Al-Haj Haasan N; Li C; Rathbone J. Clozapine versus typical neuroleptic medication for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2009, (1): CD000059. PMID 19160174. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000059.pub2.

- ^ Ananth J; Parameswaran S; Gunatilake S; Burgoyne K; Sidhom T. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome and atypical antipsychotic drugs. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2004-04, 65 (4): 464–70. PMID 15119907. doi:10.4088/JCP.v65n0403.

- ^ 164.0 164.1 McEvoy JP. Risks versus benefits of different types of long-acting injectable antipsychotics. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006,. 67 Suppl 5: 15–8. PMID 16822092.

- ^ Kenneth S. Koblan, Ph.D., Justine Kent, M.D., Seth C. Hopkins, Ph.D., John H. Krystal, M.D., Hailong Cheng, Ph.D., Robert Goldman, Ph.D., and Antony Loebel, M.D. A Non–D2-Receptor-Binding Drug for the Treatment of Schizophrenia. NEJM. April 16, 2020 [2020-12-27]. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1911772. (原始內容存檔於2021-02-23).

- ^ 166.0 166.1 Pharoah F; Mari J; Rathbone J; Wong W. Family intervention for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2010, 12 (12): CD000088. PMID 21154340. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000088.pub3.

- ^ Medalia A; Choi J. Cognitive remediation in schizophrenia. (PDF). Neuropsychology Rev. 2009, 19 (3): 353–364. PMID 19444614. doi:10.1007/s11065-009-9097-y. (原始內容存檔 (PDF)於2016-10-23).

- ^ Dixon LB, Dickerson F, Bellack AS, et al. The 2009 schizophrenia PORT psychosocial treatment recommendations and summary statements. Schizophr Bull. 2010-01, 36 (1): 48–70. PMC 2800143

. PMID 19955389. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbp115.

. PMID 19955389. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbp115.

- ^ Jauhar S, McKenna PJ, Radua J, et al. Cognitive-behavioural therapy for the symptoms of schizophrenia: systematic review and meta-analysis with examination of potential bias. The British Journal of Psychiatry (Review). 2014-01, 204 (1): 20–9. PMID 24385461. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.112.116285.

- ^ Jones C; Hacker D; Cormac I; Meaden A; Irving CB. Cognitive behaviour therapy versus other psychosocial treatments for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2012, 4 (4): CD008712. PMID 22513966. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008712.pub2.

- ^ Eichner C, Berna F. Acceptance and Efficacy of Metacognitive Training (MCT) on Positive Symptoms and Delusions in Patients With Schizophrenia: A Meta-analysis Taking Into Account Important Moderators. Schizophrenia Bulletin. July 2016, 42 (4): 952–62. PMC 4903058

. PMID 26748396. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbv225.

. PMID 26748396. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbv225.

- ^ van Oosterhout B, Smit F, Krabbendam L, Castelein S, Staring AB, van der Gaag M. Metacognitive training for schizophrenia spectrum patients: a meta-analysis on outcome studies. Psychological Medicine. January 2016, 46 (1): 47–57. PMID 26190517. doi:10.1017/s0033291715001105.

- ^ Liu, YC; Tang, CC; Hung, TT; Tsai, PC; Lin, MF. The Efficacy of Metacognitive Training for Delusions in Patients With Schizophrenia: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials Informs Evidence-Based Practice.. Worldviews on evidence-based nursing. April 2018, 15 (2): 130–139. PMID 29489070. doi:10.1111/wvn.12282.

- ^ Ruddy R; Milnes D. Art therapy for schizophrenia or schizophrenia-like illnesses.. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2005, (4): CD003728. PMID 16235338. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003728.pub2. (原始內容存檔於2011-10-27).

- ^ Ruddy RA; Dent-Brown K. Drama therapy for schizophrenia or schizophrenia-like illnesses.. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2007, (1): CD005378. PMID 17253555. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005378.pub2. (原始內容存檔於2011-08-25).

- ^ Mössler, K; Chen, X; Heldal, TO; Gold, C. Music therapy for people with schizophrenia and schizophrenia-like disorders.. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2011-12-07, (12): CD004025. PMID 22161383. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004025.pub3.

- ^ Erlangsen A; Eaton WW; Mortensen PB; Conwell Y. Schizophrenia--a predictor of suicide during the second half of life?. Schizophrenia Research. 2012-02, 134 (2-3): 111–7. PMID 22018943. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2011.09.032.

- ^ Saha S; Chant D; McGrath J. A systematic review of mortality in schizophrenia: is the differential mortality gap worsening over time?. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2007-10, 64 (10): 1123–31. PMID 17909124. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.64.10.1123.

- ^ Ustün TB, Rehm J, Chatterji S, Saxena S, Trotter R, Room R, Bickenbach J. Multiple-informant ranking of the disabling effects of different health conditions in 14 countries. The Lancet. 1999, 354 (9173): 111–15. PMID 10408486. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(98)07507-2.

- ^ World Health Organization. The global burden of disease : 2004 update [Online-Ausg.] Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. 2008: 35. ISBN 9789241563710.

- ^ Warner R. Recovery from schizophrenia and the recovery model. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2009-07, 22 (4): 374–80. PMID 19417668. doi:10.1097/YCO.0b013e32832c920b.

- ^ Menezes NM; Arenovich T; Zipursky RB. A systematic review of longitudinal outcome studies of first-episode psychosis. Psychol Med. 2006-10, 36 (10): 1349–62. PMID 16756689. doi:10.1017/S0033291706007951.

- ^ Isaac M; Chand P; Murthy P. Schizophrenia outcome measures in the wider international community. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 2007-08, 50: s71–7. PMID 18019048. doi:10.1192/bjp.191.50.s71.

- ^ Cohen A; Patel V; Thara R; Gureje O. Questioning an axiom: better prognosis for schizophrenia in the developing world?. Schizophr Bull. 2008-03, 34 (2): 229–44. PMC 2632419

. PMID 17905787. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbm105.

. PMID 17905787. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbm105.

- ^ Burns J. Dispelling a myth: developing world poverty, inequality, violence and social fragmentation are not good for outcome in schizophrenia. Afr J Psychiatry (Johannesbg). 2009-08, 12 (3): 200–5. PMID 19894340. doi:10.4314/ajpsy.v12i3.48494.

- ^ Palmer BA; Pankratz VS; Bostwick JM. The lifetime risk of suicide in schizophrenia: a reexamination. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005-03, 62 (3): 247–53. PMID 15753237. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.62.3.247.

- ^ 187.0 187.1 Carlborg A; Winnerbäck K; Jönsson EG; Jokinen J; Nordström P. Suicide in schizophrenia. Expert Rev Neurother. 2010-07, 10 (7): 1153–64. PMID 20586695. doi:10.1586/ern.10.82.

- ^ De Leon J; Diaz FJ. A meta-analysis of worldwide studies demonstrates an association between schizophrenia and tobacco smoking behaviors. Schizophrenia Research. 2005, 76 (2–3): 135–57. PMID 15949648. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2005.02.010.

- ^ 189.0 189.1 Keltner NL; Grant JS. Smoke, Smoke, Smoke That Cigarette. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care. 2006, 42 (4): 256–61. PMID 17107571. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6163.2006.00085.x.

- ^ American Psychiatric Association. Task Force on DSM-IV. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV-TR. American Psychiatric Pub. ISBN 978-0-89042-025-6. p. 304

- ^ American Psychiatric Association. Task Force on DSM-IV. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV-TR. American Psychiatric Pub. ISBN 978-0-89042-025-6. p. 314

- ^ Cascio MT; Cella M; Preti A; Meneghelli A; Cocchi A. Gender and duration of untreated psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Early intervention in psychiatry (Review). 2012-05, 6 (2): 115–27. PMID 22380467. doi:10.1111/j.1751-7893.2012.00351.x.

- ^ Kumra S; Shaw M; Merka P; Nakayama E; Augustin R. Childhood-onset schizophrenia: research update. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2001, 46 (10): 923–30. PMID 11816313.

- ^ Hassett A, Ames D, Chiu E (編). Psychosis in the Elderly. London: Taylor and Francis. 2005: 6. ISBN 1-84184-394-6.

- ^ Jablensky A, Sartorius N, Ernberg G, et al. Schizophrenia: manifestations, incidence and course in different cultures. A World Health Organization ten-country study. Psychological Medicine Monograph Supplement. 1992, 20: 1–97. PMID 1565705. doi:10.1017/S0264180100000904.

- ^ Kirkbride JB, Fearon P, Morgan C, et al. Heterogeneity in incidence rates of schizophrenia and other psychotic syndromes: findings from the 3-center AeSOP study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2006-03, 63 (3): 250–8. PMID 16520429. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.63.3.250.

- ^ Kirkbride JB, Fearon P, Morgan C, et al. Neighbourhood variation in the incidence of psychotic disorders in Southeast London. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2007, 42 (6): 438–45. PMID 17473901. doi:10.1007/s00127-007-0193-0.

- ^ Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012-12, 380 (9859): 2095–128. PMID 23245604. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0.

- ^ Ayuso-Mateos JL. Global burden of schizophrenia in the year 2000 (PDF). World Health Organization. [2013-12-27]. (原始內容存檔 (PDF)於2016-03-04).

- ^ Schizophrenia. [2015-12-29]. (原始內容存檔於2016-10-04).

- ^ Schneider K. Clinical Psychopathology 5. New York: Grune & Stratton. 1959.

- ^ Nordgaard J; Arnfred SM; Handest P; Parnas J. The diagnostic status of first-rank symptoms. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2008-01, 34 (1): 137–54. PMC 2632385

. PMID 17562695. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbm044.

. PMID 17562695. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbm044.

- ^ Yuhas, Daisy. Throughout History, Defining Schizophrenia Has Remained a Challenge. Scientific American Mind (March/April 2013). [2013-03-03]. (原始內容存檔於2013-11-05).

- ^ Heinrichs RW. Historical origins of schizophrenia: two early madmen and their illness. Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences. 2003, 39 (4): 349–63. PMID 14601041. doi:10.1002/jhbs.10152.

- ^ Noll, Richard. American madness: the rise and fall of dementia praecox. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. 2011. ISBN 978-0-674-04739-6.

- ^ Noll R. Whole body madness. Psychiatric Times. 2012, 29 (12): 13–14. (原始內容存檔於2013-01-11).

- ^ Hansen RA; Atchison B. Conditions in occupational therapy: effect on occupational performance. Hagerstown, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2000. ISBN 0-683-30417-8.

- ^ Berrios G.E.; Luque R; Villagran J. Schizophrenia: a conceptual history. International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy. 2003, 3 (2): 111–140.

- ^ Kuhn R. tr. Cahn CH. Eugen Bleuler's concepts of psychopathology. History of Psychiatry. 2004, 15 (3): 361–6. PMID 15386868. doi:10.1177/0957154X04044603.

- ^ Stotz-Ingenlath G. Epistemological aspects of Eugen Bleuler's conception of schizophrenia in 1911 (PDF). Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy. 2000, 3 (2): 153–9 [2016-11-26]. PMID 11079343. doi:10.1023/A:1009919309015. (原始內容存檔於2020-03-31).

- ^ McNally K. Eugen Bleuler's "Four A's". History of Psychology. 2009, 12 (2): 43–59. PMID 19831234. doi:10.1037/a0015934.

- ^ Turner T. Unlocking psychosis. British Medical Journal. 2007, 334 (suppl): s7. PMID 17204765. doi:10.1136/bmj.39034.609074.94.

- ^ Wing JK. International comparisons in the study of the functional psychoses. British Medical Bulletin. 1971-01, 27 (1): 77–81. PMID 4926366.

- ^ Rosenhan D. On being sane in insane places. Science. 1973, 179 (4070): 250–8. Bibcode:1973Sci...179..250R. PMID 4683124. doi:10.1126/science.179.4070.250.

- ^ Wilson M. DSM-III and the transformation of American psychiatry: a history. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1993-03, 150 (3): 399–410. PMID 8434655. doi:10.1176/ajp.150.3.399.

- ^ Stotz-Ingenlath G. Epistemological aspects of Eugen Bleuler's conception of schizophrenia in 1911. Med Health Care Philos. 2000, 3 (2): 153–159. PMID 11079343. doi:10.1023/A:1009919309015.

- ^ 217.0 217.1 Hayes J. A.; Mitchell J. C. Mental health professionals' skepticism about multiple personality disorder. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 1994, 25 (4): 410–415. doi:10.1037/0735-7028.25.4.410.

- ^ Putnam, Frank W. (1989). Diagnosis and Treatment of Multiple Personality Disorder. New York: The Guilford Press. pp. 351. ISBN 0-89862-177-1

- ^ Berrios, G. E.; Porter, Roy. A history of clinical psychiatry: the origin and history of psychiatric disorders. London: Athlone Press. 1995. ISBN 0-485-24211-7.

- ^ McNally K. Schizophrenia as split personality/Jekyll and Hyde: the origins of the informal usage in the English language. Journal of the history of the behavioral sciences. Winter 2007, 43 (1): 69–79. PMID 17205539. doi:10.1002/jhbs.20209.

- ^ Kim Y; Berrios GE. Impact of the term schizophrenia on the culture of ideograph: the Japanese experience. Schizophr Bull. 2001, 27 (2): 181–5. PMID 11354585. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006864.

- ^ Sato M. Renaming schizophrenia: a Japanese perspective. World Psychiatry. 2004, 5 (1): 53–55. PMC 1472254

. PMID 16757998.

. PMID 16757998.

- ^ Lee YS; Kim JJ; Kwon JS. Renaming schizophrenia in South Korea. The Lancet. 2013-08, 382 (9893): 683–684. PMID 23972810. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61776-6.

- ^ 陳大申. 精神分裂症正名為「思覺失調症」新一代抗精神病藥物有助生活品質. KingNet國家網路醫藥. 2014-06-21 [2016-11-28]. (原始內容存檔於2016-11-28).

- ^ van Os, Jim. 'Schizophrenia' does not exist. BMJ. 2016-02-02: i375. doi:10.1136/bmj.i375.

- ^ Wu EQ. The economic burden of schizophrenia in the United States in 2002. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005, 66 (9): 1122–9. PMID 16187769. doi:10.4088/jcp.v66n0906.

- ^ 李文. 新聞人物:「美麗心靈」數學家約翰·納什. BBC. 2015-05-24 [2016-11-28]. (原始內容存檔於2016-11-28).

- ^ 毛艷艷; 謝國旗. 沙耆故居:宁静藜斋护天真. 東南商報 (寧波文化遺產保護網). 2007-02-05 [2016-11-30]. (原始內容存檔於2016-12-01).

- ^ Maniglio R. Severe mental illness and criminal victimization: a systematic review. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2009-03, 119 (3): 180–91. PMID 19016668. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01300.x.

- ^ 230.0 230.1 Fazel S; Gulati G; Linsell L; Geddes JR; Grann M. Schizophrenia and violence: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2009-08, 6 (8): e1000120. PMC 2718581

. PMID 19668362. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000120.

. PMID 19668362. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000120.

- ^ Large M; Smith G; Nielssen O. The relationship between the rate of homicide by those with schizophrenia and the overall homicide rate: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr. Res. 2009-07, 112 (1–3): 123–9. PMID 19457644. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2009.04.004.

- ^ Bo S; Abu-Akel A; Kongerslev M; Haahr UH; Simonsen E. Risk factors for violence among patients with schizophrenia. Clin Psychol Rev. 2011-07, 31 (5): 711–26. PMID 21497585. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2011.03.002.

- ^ 233.0 233.1 Valença, Alexandre Martins; de Moraes, Talvane Marins. Relationship between homicide and mental disorders. Revista Brasileira De Psiquiatria (Sao Paulo, Brazil: 1999). 2006-10-01,. 28 Suppl 2: S62–68. ISSN 1516-4446. PMID 17143446. (原始內容存檔於2016-11-24).

- ^ Pescosolido BA; Monahan J; Link BG; Stueve A; Kikuzawa S. The public's view of the competence, dangerousness, and need for legal coercion of persons with mental health problems. American Journal of Public Health. 1999-09, 89 (9): 1339–45. PMC 1508769

. PMID 10474550. doi:10.2105/AJPH.89.9.1339.

. PMID 10474550. doi:10.2105/AJPH.89.9.1339.

- ^ Phelan JC; Link BG; Stueve A; Pescosolido BA. Public Conceptions of Mental Illness in 1950 and 1996: What Is Mental Illness and Is It to be Feared?. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2000-06, 41 (2): 188–207. doi:10.2307/2676305.

- ^ Dean OM; Data-Franco J; Giorlando F; Berk M. Minocycline: therapeutic potential in psychiatry. CNS Drugs. 2012-05-01, 26 (5): 391–401. PMID 22486246. doi:10.2165/11632000-000000000-00000.

- ^ Chamberlain IJ, Sampson S. Chamberlain, Ian J , 編. Nidotherapy for people with schizophrenia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2013-03-28, 3 (3): CD009929. PMID 23543583. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009929.pub2.

- ^ Chue P; LaLonde JK. Addressing the unmet needs of patients with persistent negative symptoms of schizophrenia: emerging pharmacological treatment options. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2014, 10: 777–89. PMC 4020880

. PMID 24855363. doi:10.2147/ndt.s43404.

. PMID 24855363. doi:10.2147/ndt.s43404.

- ^ Keller WR; Kum LM; Wehring HJ; Koola MM; Buchanan RW; Kelly DL. A review of anti-inflammatory agents for symptoms of schizophrenia. J Psychopharmacol. 2013, 27 (4): 337–42. PMID 23151612. doi:10.1177/0269881112467089.

參見

[編輯]外部連結

[編輯]- 開放目錄專案中的「思覺失調症」

- Schizophrenia (頁面存檔備份,存於網際網路檔案館) (英文) - WHO

- Schizophrenia (頁面存檔備份,存於網際網路檔案館) (英文) - NIMH

- Psychosis and schizophrenia (頁面存檔備份,存於網際網路檔案館) (英文) - NICE Pathways