用户:Ericliu1912/沙盒8

新党 | |

|---|---|

| File:New Party logo.svg 新党党徽 | |

| 英语名称 | New Party |

| 主席 | 吴成典 |

| 副主席 | 李胜峰 |

| 秘书长 | 潘怀宗 |

| 副秘书长 | 郝永瑞、陈丽玲、苏恒 |

| 发言人 | 王炳忠 |

| 创始人 | 赵少康、郁慕明、王建煊、陈癸淼、李庆华、李胜峰、周荃 |

| 成立 | 1993年8月10日 |

| 合并自 | 中华社会民主党(1994年) |

| 分裂自 | 中国国民党 |

| 前身 | 新国民党连线 |

| 总部 | |

| 党报 | 《新月刊》 |

| 青年组织 | 新党青年军 |

| 意识形态 | 三民主义 宪政主义 中国民族主义 社会民主主义 文化保守主义 民族保守主义 |

| 政治立场 | 右派至极右派 |

| 官方色彩 | 黄色 |

| 党歌 | 《大地一声雷》 《小雨滴》 |

| 立法委员 | 0 / 113 |

| 直辖市市长 | 0 / 6 |

| 直辖市议员 | 2 / 380 |

| 县市长 | 0 / 16 |

| 县市议员 | 0 / 532 |

| 乡镇市区长 | 0 / 204 |

| 乡镇市区民代表 | 0 / 2,148 |

| 村里长 | 0 / 7,744 |

| 党旗 | |

| File:New Party flag.svg | |

| 官方网站 | |

| http://www.np.org.tw/ | |

| 中华民国政治 政党 · 选举 | |

新党是中华民国的政党之一,前身为中国国民党党内少壮派成员成立的立法院次级问政团体新国民党连线。由于与时任国民党主席、中华民国总统李登辉的矛盾加剧,1993年8月10日,赵少康、郁慕明、王建煊、陈癸淼、李庆华、李胜峰、周荃等七人召开记者会宣布正式成立新党,脱离国民党。之后,新党参与1993年县市长选举、1994年县市议员选举和省市长暨省市议员选举皆有斩获,1994年底与中华社会民主党合并后,更在1995年立法委员选举中一举获得21席、在1996年国民大会代表选举中获得46席,一度成为中国国民党、民主进步党之后的第三大党。作为国会中的关键少数,新党曾和当时同样在野的民进党“大和解”,并共同推动二月政改。不过自1996年起,新党因党内意见分歧等问题,选举连年不利,而自亲民党于2000年成立后,更使新党流失大量支持基础,在2001年立法委员选举中被亲民党和台湾团结联盟超越,退居国会第五大党,逐渐泡沫化。2008年立法委员选举后,新党失去在国会的所有席次,政党得票率更在2012年立法委员选举中被绿党超越。尽管新党在2016年立法委员选举中政党得票率一度有所回升,但在2020年立法委员选举中又遭重挫,政党得票率仅1.04%,创下历年最低纪录,退居为全国第八大党。目前,新党仅在台北市议会占有两席议员。现任新党党主席为吴成典。

新党早年在政治光谱中处于中间偏右,后转向右派至极右派。作为台湾的统派代表性政党,新党自许为《中华民国宪法》的捍卫者,秉持“清廉制衡、公义均富、族群和谐、国家统一”的理念,主张“和统保台、反台独、反黑金、反特权、爱国家、爱民族”、“以三民主义统一中国”,坚持一个中国、九二共识,同时亦支持协商一国两制台湾方案。此外,新党主张宪政民主、内阁制,并主张实施福利政策,以缩小贫富差距。

历史[编辑]

草创期(1989年-1994年)[编辑]

新党的前身是中国国民党党内少壮派成员成立的立法院次级问政团体新国民党连线(简称为新连线)。新连线由时任立法委员赵少康、李胜峰等人成立于1989年8月25日,主张“保存总理孙中山先生一脉相传开创之精神,并挽救走向金权政治及台独执政的危机”,期望以“体制内的运作”改革国民党。新连线的成员组成以外省人为主,在立场上常与当时以本省人、党主席李登辉为首,主张走“本土化”路线的国民党中央有所相左。1990年,“二月政争”爆发,以李登辉为首的“主流派”击败以李焕、郝柏村等外省人为首的“非主流派”,此后新连线成员与李登辉的矛盾日渐加剧。1992年立委选举中,许多新连线成员未获国民党中央提名,于是自行以无党籍身分参选,结果大获全胜,形成一股势力。在追求党内民主和改革的做法不被接受之下,新连线于1993年2月于国父纪念馆举办“请问总统先生”问政说明会,吸引了四、五千名听众。1993年3月,新连线决定号召成员在全台各地举行国是说明会,在台北市、台中市、高雄市举办“新国民党中兴大会师”、“追思总理、浴火重生,一个新国民党的诞生”、“南北新连线、拯救美丽岛”等三场大型演讲,其中在台北和台中举办的演讲更分别有近一万和五千馀名听众捧场。3月14日,新连线成员在前往高雄中学准备高雄场次的演讲时,遭到当地民主进步党人士和群众包围袭击,最终演变为流血冲突,是为“三一四事件”。事后,新连线成员面对警察保护不力、生命一度受到威胁的危机,以及国民党中央对其冷嘲热讽等情况,认为国民党中央企图与民进党联手对付新连线,遂使其脱离国民党、另立新政党的动机日深。

新国民党连线与国民党中央的龃龉于1993年的中国国民党第十四次全国代表大会前夕达到高峰。会前,新连线要求党主席由全体党员普选产生,以及中央常务委员、中央委员采登记制,并由一人一票方式选举产生等主张,但皆未获得高层采纳,且国民党主流派不断挑起省籍问题,在此情形下,新连线成员对于国民党的疏离感更加强烈。在和国民党中央沟通多次无效后,新连线成员最终不得不寻求“体制外的改革”,即另组政党。1993年5月,新国民党连线向内政部登记成立政治团体,与国民党走向“形式团结、实质分裂”之路;8月10日,赵少康、郁慕明、王建煊、陈癸淼、李庆华、李胜峰、周荃等七人召开记者会宣布正式成立“新党”,脱离国民党。8月22日,“新党全国竞选暨发展委员会”(简称为全委会)成立,会中除通过新党党章外,并选举赵少康为首任全委会召集人。

新党成立后,随即面临当年年底举行的县市长选举。在当次选举中,新党提名李胜峰参选台北县县长(今新北市市长)、谢启大参选新竹市市长。选前三天的11月24日,时任国民党中常委、前行政院国军退除役官兵辅导委员会主委许历农宣布退出国民党加入新党,引发政坛震撼。选举结果,新党籍候选人在台北县取得21万5,000馀票(得票率16.3%),在新竹市取得1万5,000馀票(得票率10.1%),总计二者共占全省得票数的3.1%,对于成立甫满三个月的新党来说算是差强人意的表现。之后,新党在1994年初举行的县市议员选举中拿下8席县市议员。当年7月13日,郁慕明出任第二任全委会召集人。

1994年年底举行的省市长选举是中华民国政府迁台后首次一级行政区行政首长直选。在这次选举中,新党提名赵少康参选台北市市长、汤阿根参选高雄市市长、时属中华社会民主党的朱高正参选台湾省省长(副省长搭档为新党籍的姚立明)。其中,赵少康以“保卫中华民国”、“建立新秩序”等主张为诉求,为台北市市长选战刮起了旋风。9月25日,新党“南进”至高雄劳工公园举行市长选举造势说明会时,再度遭到民进党支持者闹场,双方发生严重肢体冲突,多人挂彩受伤,是为“九二五事件”。10月22日,王建煊出任第三任全委会召集人。11月11日,由小轩作词、谭健常作曲、民歌歌手李建复主唱的新党之歌《大地一声雷》发表。最终,尽管赵少康因弃保效应以近42万5,000票(得票率30.17%)的得票数败于民进党提名的陈水扁,汤阿根跟朱高正亦铩羽而归,但新党“母鸡带小鸡”的选举策略奏效,在台北市取得11席市议员、在高雄市取得2席市议员、在台湾省取得2席省议员,更因此使台北市议会首次“三党不过半”。12月28日,中华社会民主党与新党对等合并。

鼎盛期(1995年-1996年)[编辑]

1995年4月底,新党将中央党部由位于中正区青岛东路的办公室迁至松山区光复南路现址。7月20日,党营广播电台“新党之音”(“新希望”)开播,为新党开辟了发声管道。8月22日,陈癸淼出任第四任全委会召集人,同日新党决定提名王建煊为隔年首届民选总统选举候选人。8月23日至9月6日,王建煊率团访问美国宣扬新党理念,所到之处广受欢迎,当时北美地区大型中文报纸《世界日报》社论更宣称新党“俨然已是海外第一大党”。不过,为能成功整合第三势力,王建煊在当年12月10日宣布退出总统选举,新党改支持以无党籍身分参选正、副总统的林洋港与郝柏村。

自1976年解除戒严和党禁后,工党、劳动党和中华社会民主党等第三势力政党接连出现,但或未成气候、或昙花一现,无法打破国民党和民进党两党抗衡的政治框架;新党的兴起,让这一局面有所变化。1995年年底举行的立委选举是新党成立以来首次以政党名义参加的立委选举。新党的选战策略大致以“三党不过半”为主轴,以小市民和中产阶级为主要诉求对象。选举结果,新党大获全胜,拿下21席立委,得票数122万馀票、得票率达12.95%,虽仍无法实现“三党不过半”的目标[注 1],但仍成功“跨越浊水溪,甚至高屏溪”,在南台湾县市夺得席次,并站稳国民党、民进党之后全国第三大政党的地位。

1995年立委选举后,国民党丧失一党独大优势,在野党首次有机会取得议事主导权。1995年12月14日,新党与民进党在立法院咖啡厅举行结盟会谈“大和解”,确定双方合作意愿。为对抗国民党,民进党还拉拢国民党籍的原住民立委。1996年2月2日第三届立法院开议,当日举行立法院院长与立法院副院长选举,由国民党提名的刘松藩与王金平(时任立法院正、副院长)对上民进党提名、新党支持的施明德(民进党主席)与蔡中涵(国民党籍原住民立委);结果在激烈的朝野攻防战中,刘、王惊险连任正、副院长,其中刘在第一轮投票中与施平手,在第二轮投票中仅以一票险胜。最终“二月政改”虽功亏一篑,惟仍展现了新党“关键少数”的力量。

衰落期(1997年-2001年)[编辑]

http://china-taiwan-newparty.com/History

http://rportal.lib.ntnu.edu.tw/bitstream/20.500.12235/85352/2/000602.pdf

http://rportal.lib.ntnu.edu.tw/bitstream/20.500.12235/85354/4/000404.pdf

http://rportal.lib.ntnu.edu.tw/bitstream/20.500.12235/85352/4/000604.pdf

https://www.chinatimes.com/realtimenews/20200313000020-260407?chdtv

https://www.ios.sinica.edu.tw/people/personal/fcwang/fcwang2004-1.pdf

https://ah.nccu.edu.tw/retrieve/79461/52501301.pdf

https://www.haixia-info.com/articles/786.html

http://depthis.ccu.edu.tw/allnum/03/0320.xls.html

https://www.peoplenews.tw/news/ab606fe2-a944-4d3e-92fc-e4ef7794f018

http://news.bbc.co.uk/hi/chinese/news/newsid_1673000/16733492.stm

https://ah.nccu.edu.tw/item?item_id=76759

https://www.haixia-info.com/articles/1239.html

https://www.gvm.com.tw/search?keywords=%E8%B6%99%E5%B0%91%E5%BA%B7&page=2

https://www.gvm.com.tw/article/3699

https://www.chinatimes.com/realtimenews/20180703002402-260407?chdtv

https://news.tvbs.com.tw/politics/74579

https://www.ocacnews.net/overseascommunity/article/article_story.jsp?id=50760

https://www.cna.com.tw/project/20191107-election/part2.html

http://www.jestw.com/upload/journal/29/10-1%20陳文俊.pdf

http://rportal.lib.ntnu.edu.tw/bitstream/20.500.12235/85352/8/000608.pdf

https://www.taiwan-panorama.com/Articles/Details?Guid=76eb964d-ee50-4767-a5b3-d3078507d200&CatId=7

https://www.gvm.com.tw/article/2975

https://ndltd.ncl.edu.tw/cgi-bin/gs32/gsweb.cgi/login?o=dnclcdr&s=id="091NSYS5227026".&searchmode=basic

https://www.haixia-info.com/articles/864.html

https://www.zo.uni-heidelberg.de/md/zo/sino/research/10_taiwanduoyuanwenhua.pdf

https://www.ios.sinica.edu.tw/people/personal/fcwang/fcwang1998-2.pdf

https://www.storm.mg/article/2902709

http://www.crntt.tw/doc/1056/3/2/1/105632120.html

https://nccur.lib.nccu.edu.tw/bitstream/140.119/28060/1/50_02.pdf

https://www.fhk.ndu.edu.tw/site/main/upload/6862ac282432fc1fde400aa74f317621/journal/76-01.pdf

震荡起伏期(2002年至今)[编辑]

组织架构[编辑]

新党在成立之初属于柔性政党,以“全国竞选暨发展委员会”(简称为全委会)为最高权力机关,采取集体领导制,不设党主席,仅由全委会委员互推产生一名召集人主持全委会会议。全委会并设有秘书长一职,由召集人提名、全委会同意后聘任,负责综理党内事务,并指挥及监督所属人员。郁慕明曾将此一制度概括为“一党、两脚、三人”,其中“一党”指全委会,“两脚”指党务和义工系统,“三人”则是指各发展委员会召集人、义工组织的报告人和负责各地区义工组织与党部联系的联络人。

2002年,新党修改党章,改组为刚性政党。新版的新党党章规定以“全国党员代表大会”(简称为全代会)为最高权力机关,每年集会一次。全代会代表包含由党员直选之党代表、党内乡镇市区民代表以上之公职人员,以及“全国委员会”(仍简称为全委会)委员。全委会是全代会闭会期间的最高党务机关,其委员包含党主席、副主席、秘书长、现任县市以上政府正副首长、立法院党团正副召集人、各县市议会党团正副召集人,以及经全代会所选出者。新党党主席由全体党员以无记名投票选举产生,每任任期二年。秘书长一职则改由主席提名、全委会同意后聘任。此外,新党还设有廉政勤政委员会(简称为廉勤会)为党务仲裁机关。

现任新党党主席为吴成典,于2020年2月21日就任。

政治立场[编辑]

党际关系[编辑]

选举表现[编辑]

国家元首选举[编辑]

国会选举[编辑]

- 国民大会

| 选举 | 得票数 | % | ± | 取得席次 | ± | 名次 | ± |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1996年 | 1,425,896 | 13.67 | 不适用 | 46 / 334

|

不适用 | 3 | 不适用 |

| 2005年 | 34,253 | 0.88 | ▼ 12.79 | 3 / 300

|

▼ 43 | 6 | ▼ 3 |

- 立法院

| 选举 | 得票数 | % | ± | 取得席次 | ± | 名次 | ± | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1995年 | 1,222,931 | 12.95 | 不适用 | 21 / 164

|

不适用 | 3 | 不适用 | ||||||

| 1998年 | 708,465 | 7.06 | ▼ 5.89 | 11 / 225

|

▼ 10 | 3 | ━ | ||||||

| 2001年 | 269,620 | 2.61 | ▼ 4.45 | 1 / 225

|

▼ 10 | 5 | ▼ 2 | ||||||

| 2004年 | 12,137 | 0.12 | ▼ 2.49 | 1 / 225

|

━ | 6 | ▼ 1 | ||||||

| 选举 | 区域立委 | 原住民立委 | 不分区及侨民立委 | 取得席次 | ± | 名次 | ± | ||||||

| 得票数 | % | ± | 得票数 | % | ± | 得票数 | % | ± | |||||

| 2008年 | - | - | 不适用 | - | - | 不适用 | 386,660 | 3.95 | 不适用 | 0 / 113

|

━ | 不适用 | 不适用 |

| 2012年 | 10,678 | 0.08 | ▲ 0.08 | - | - | - | 195,960 | 1.49 | ▼ 2.46 | 0 / 113

|

━ | 不适用 | 不适用 |

| 2016年 | 75,372 | 0.63 | ▲ 0.55 | - | - | - | 510,074 | 4.18 | ▲ 2.69 | 0 / 113

|

━ | 不适用 | 不适用 |

| 2020年 | - | - | ▼ 0.63 | - | - | - | 147,373 | 1.04 | ▼ 4.14 | 0 / 113

|

━ | 不适用 | 不适用 |

地方选举[编辑]

|

|

|

|

参见[编辑]

注释[编辑]

参考资料[编辑]

外部链接[编辑]

- 官方网站 (繁体中文)

- 新党的Facebook专页

| 理察·费曼 Richard Feynman | |

|---|---|

| 出生 | 理察·菲利普斯·费曼 Richard Phillips Feynman 1918年5月11日 |

| 逝世 | 1988年2月15日(69岁) |

| 墓地 | 加州阿尔塔迪纳山景公墓和陵墓 (Mountain View Cemetery and Mausoleum) |

| 母校 | 麻省理工学院 普林斯顿大学 |

| 知名于 | 费曼方格图 费曼图 费曼规范 费曼参数化 费曼点 费曼传播子 费曼斜线标记 费曼喷头 费曼-卡茨公式 费曼-海尔曼定理 费曼-斯蒂克尔堡诠释 《费曼物理学讲义》 贝特-费曼公式 惠勒-费曼吸收体理论 量子细胞自动机 量子计算 量子电动力学 量子流体动力学 量子乱流 量子模拟器 声波方程式 V-A理论 布朗棘轮 奈米技术 单电子宇宙 部分子模型 路径积分表述 传递桨轴 黏珠论点 同步分子马达 涡环模型 曼哈顿计划 罗杰斯委员会 邦哥鼓技能 |

| 配偶 | 阿琳·格林鲍姆 (1919年-1945年) (1941年结婚) 玛丽·路易丝·贝尔 (1917年-?) (1952年-1956年结婚) 格维内斯·霍华斯 (1934年-1989年) (1960年结婚) |

| 儿女 | 2 |

| 奖项 | 阿尔伯特·爱因斯坦奖(1954年) 欧内斯特·劳伦斯奖(1962年) 诺贝尔物理学奖(1965年) 奥斯特奖章(1972年) 尼尔斯·波耳奖章(1973年) 美国国家科学奖章(1979年) |

| 科学生涯 | |

| 研究领域 | 理论物理学 |

| 机构 | 康乃尔大学 加利福尼亚理工学院 |

| 论文 | 《量子力学中的最小作用量原理》(The Principle of Least Action in Quantum Mechanics) (1942年) |

| 博士导师 | 约翰·惠勒 |

| 博士生 | 杰姆斯·马克士威·巴丁 罗利·布朗 托马斯·库特莱特 阿尔伯特·希布斯 乔瓦尼·罗西·洛马尼茨 乔治·茨威格 |

| 其他著名学生 | 罗伯特·巴罗 丹尼·希利斯 道格拉斯·奥谢罗夫 保罗·斯泰恩哈特 史蒂芬·沃尔夫勒姆 |

| 签名 | |

| |

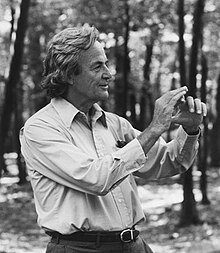

理察·菲利普斯·“迪克”·费曼,ForMemRS(英语:Richard Phillips "Dick" Feynman [/ˈfaɪnmən/],1918年5月11日—1988年2月15日)[1][2][3][4],是一名美国理论物理学家,以其对量子力学中的路径积分表述、量子电动力学理论、过冷液氦的超流性以及粒子物理学中部分子模型的研究闻名。因对量子电动力学的贡献,他于1965年与朱利安·施温格和朝永振一郎共同获得诺贝尔物理学奖。

费曼发明了一种获得广泛应用的形象化次原子粒子行为数学描述方法,后人称之为费曼图。费曼在世时是世界上最有名的科学家之一。在英国学术期刊《物理世界》于1999年举办、全球130位顶尖物理学家参与的投票中,费曼名列十大有史以来最伟大的物理学家之一[5]。

费曼在第二次世界大战期间曾参与原子弹的开发,后于1980年代因身为挑战者号太空梭灾难调查单位罗杰斯委员会参与成员之一而为公众熟知。在理论物理学研究之外,他还是量子计算领域的先驱,并首先提出了奈米技术的概念。此外,费曼还曾担任加利福尼亚理工学院的理察·托尔曼理论物理学教授。

费曼热心参与物理学普及事业,为此写过书籍和举办讲座,包括了1959年有关自上而下的奈米技术演讲《底部有的是空间》和1964年初版的三卷本本科讲座讲义《费曼物理学讲义》。他同时以半自传《别闹了,费曼先生!》和《你管别人怎么想》,以及拉尔夫·赖顿的《去图瓦还是被捕》和詹姆斯·格雷克的《天才:理察·费曼的一生与科学事业》(Genius: The Life and Science of Richard Feynman)等以他为主题的书籍闻名。

早年[编辑]

理察·菲利普斯·费曼于1918年5月11日生于美国纽约市皇后区Feynman was born on May 11, 1918, in Queens, New York City,[6] to Lucille 本姓Phillips, a homemaker, and Melville Arthur Feynman, a sales manager[7] originally from Minsk in Belarus[8] (then part of the Russian Empire). Both were Lithuanian Jews.[9] Feynman was a late talker, and did not speak until after his third birthday. As an adult he spoke with a New York accent[10][11] strong enough to be perceived as an affectation or exaggeration[12][13]—so much so that his friends Wolfgang Pauli and Hans Bethe once commented that Feynman spoke like a "bum".[12] The young Feynman was heavily influenced by his father, who encouraged him to ask questions to challenge orthodox thinking, and who was always ready to teach Feynman something new. From his mother, he gained the sense of humor that he had throughout his life. As a child, he had a talent for engineering, maintained an experimental laboratory in his home, and delighted in repairing radios. When he was in grade school, he created a home burglar alarm system while his parents were out for the day running errands.[14]

When Richard was five his mother gave birth to a younger brother, Henry Phillips, who died at age four weeks.[15] Four years later, Richard's sister Joan was born and the family moved to Far Rockaway, Queens.[7] Though separated by nine years, Joan and Richard were close, and they both shared a curiosity about the world. Though their mother thought women lacked the capacity to understand such things, Richard encouraged Joan's interest in astronomy, and Joan eventually became an astrophysicist.[16]

宗教信仰[编辑]

Feynman's parents were not religious, and by his youth, Feynman described himself as an "avowed atheist".[17] Many years later, in a letter to Tina Levitan, declining a request for information for her book on Jewish Nobel Prize winners, he stated, "To select, for approbation the peculiar elements that come from some supposedly Jewish heredity is to open the door to all kinds of nonsense on racial theory", adding, "at thirteen I was not only converted to other religious views, but I also stopped believing that the Jewish people are in any way 'the chosen people'".[18] Later in his life, during a visit to the Jewish Theological Seminary, he encountered the Talmud for the first time. He saw that it contained the original text in a little square on the page, and surrounding it were commentaries written over time by different people. In this way the Talmud had evolved, and everything that was discussed was carefully recorded, which made it a wonderful book. Despite being impressed, Feynman was disappointed with the lack of interest for nature and the outside world expressed by the rabbis, who only cared about questions which arise from the Talmud.[19]

教育[编辑]

Feynman attended Far Rockaway High School, a school in Far Rockaway, Queens, which was also attended by fellow Nobel laureates Burton Richter and Baruch Samuel Blumberg.[20] Upon starting high school, Feynman was quickly promoted into a higher math class. A high-school-administered IQ test estimated his IQ at 125—high, but "merely respectable" according to biographer James Gleick.[21][22] His sister Joan did better, allowing her to claim that she was smarter. Years later he declined to join Mensa International, saying that his IQ was too low.[23] Physicist Steve Hsu stated of the test:

I suspect that this test emphasized verbal, as opposed to mathematical, ability. Feynman received the highest score in the United States by a large margin on the notoriously difficult Putnam mathematics competition exam ... He also had the highest scores on record on the math/physics graduate admission exams at Princeton ... Feynman's cognitive abilities might have been a bit lopsided ... I recall looking at excerpts from a notebook Feynman kept while an undergraduate ... [it] contained a number of misspellings and grammatical errors. I doubt Feynman cared very much about such things.[24]

When Feynman was 15, he taught himself trigonometry, advanced algebra, infinite series, analytic geometry, and both differential and integral calculus.[25] Before entering college, he was experimenting with and deriving mathematical topics such as the half-derivative using his own notation.[26] He created special symbols for logarithm, sine, cosine and tangent functions so they did not look like three variables multiplied together, and for the derivative, to remove the temptation of canceling out the 's.[27][28] A member of the Arista Honor Society, in his last year in high school he won the New York University Math Championship.[29] His habit of direct characterization sometimes rattled more conventional thinkers; for example, one of his questions, when learning feline anatomy, was "Do you have a map of the cat?" (referring to an anatomical chart).[30]

Feynman applied to Columbia University but was not accepted because of their quota for the number of Jews admitted.[7] Instead, he attended the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he joined the Pi Lambda Phi fraternity.[31] Although he originally majored in mathematics, he later switched to electrical engineering, as he considered mathematics to be too abstract. Noticing that he "had gone too far," he then switched to physics, which he claimed was "somewhere in between."[32] As an undergraduate, he published two papers in the Physical Review.[29] One of these, which was co-written with Manuel Vallarta, was titled "The Scattering of Cosmic Rays by the Stars of a Galaxy".[33]

Vallarta let his student in on a secret of mentor-protégé publishing: the senior scientist's name comes first. Feynman had his revenge a few years later, when Heisenberg concluded an entire book on cosmic rays with the phrase: "such an effect is not to be expected according to Vallarta and Feynman." When they next met, Feynman asked gleefully whether Vallarta had seen Heisenberg's book. Vallarta knew why Feynman was grinning. "Yes," he replied. "You're the last word in cosmic rays."[34]

The other was his senior thesis, on "Forces in Molecules",[35] based on an idea by John C. Slater, who was sufficiently impressed by the paper to have it published. Today, it is known as the Hellmann–Feynman theorem.[36]

In 1939, Feynman received a bachelor's degree,[37] and was named a Putnam Fellow.[38] He attained a perfect score on the graduate school entrance exams to Princeton University in physics—an unprecedented feat—and an outstanding score in mathematics, but did poorly on the history and English portions. The head of the physics department there, Henry D. Smyth, had another concern, writing to Philip M. Morse to ask: "Is Feynman Jewish? We have no definite rule against Jews but have to keep their proportion in our department reasonably small because of the difficulty of placing them."[39] Morse conceded that Feynman was indeed Jewish, but reassured Smyth that Feynman's "physiognomy and manner, however, show no trace of this characteristic".[39]

Attendees at Feynman's first seminar, which was on the classical version of the Wheeler-Feynman absorber theory, included Albert Einstein, Wolfgang Pauli, and John von Neumann. Pauli made the prescient comment that the theory would be extremely difficult to quantize, and Einstein said that one might try to apply this method to gravity in general relativity,[40] which Sir Fred Hoyle and Jayant Narlikar did much later as the Hoyle–Narlikar theory of gravity.[41][42] Feynman received a Ph.D. from Princeton in 1942; his thesis advisor was John Archibald Wheeler.[43] In his doctoral thesis titled "The Principle of Least Action in Quantum Mechanics,"[44] Feynman applied the principle of stationary action to problems of quantum mechanics, inspired by a desire to quantize the Wheeler–Feynman absorber theory of electrodynamics, and laid the groundwork for the path integral formulation and Feynman diagrams.[45] A key insight was that positrons behaved like electrons moving backwards in time.[45] James Gleick wrote:

This was Richard Feynman nearing the crest of his powers. At twenty-three ... there may now have been no physicist on earth who could match his exuberant command over the native materials of theoretical science. It was not just a facility at mathematics (though it had become clear ... that the mathematical machinery emerging in the Wheeler–Feynman collaboration was beyond Wheeler's own ability). Feynman seemed to possess a frightening ease with the substance behind the equations, like Einstein at the same age, like the Soviet physicist Lev Landau—but few others.[43]

One of the conditions of Feynman's scholarship to Princeton was that he could not be married; nevertheless, he continued to see his high school sweetheart, Arline Greenbaum, and was determined to marry her once he had been awarded his Ph.D. despite the knowledge that she was seriously ill with tuberculosis. This was an incurable disease at the time, and she was not expected to live more than two years. On June 29, 1942, they took the ferry to Staten Island, where they were married in the city office. The ceremony was attended by neither family nor friends and was witnessed by a pair of strangers. Feynman could only kiss Arline on the cheek. After the ceremony he took her to Deborah Hospital, where he visited her on weekends.[46][47]

曼哈顿计划[编辑]

In 1941, with World War II raging in Europe but the United States not yet at war, Feynman spent the summer working on ballistics problems at the Frankford Arsenal in Pennsylvania.[48][49] After the attack on Pearl Harbor had brought the United States into the war, Feynman was recruited by Robert R. Wilson, who was working on means to produce enriched uranium for use in an atomic bomb, as part of what would become the Manhattan Project.[50][51] At the time, Feynman had not earned a graduate degree.[52] Wilson's team at Princeton was working on a device called an isotron, intended to electromagnetically separate uranium-235 from uranium-238. This was done in a quite different manner from that used by the calutron that was under development by a team under Wilson's former mentor, Ernest O. Lawrence, at the Radiation Laboratory of the University of California. On paper, the isotron was many times more efficient than the calutron, but Feynman and Paul Olum struggled to determine whether or not it was practical. Ultimately, on Lawrence's recommendation, the isotron project was abandoned.[53]

At this juncture, in early 1943, Robert Oppenheimer was establishing the Los Alamos Laboratory, a secret laboratory on a mesa in New Mexico where atomic bombs would be designed and built. An offer was made to the Princeton team to be redeployed there. "Like a bunch of professional soldiers," Wilson later recalled, "we signed up, en masse, to go to Los Alamos."[54] Like many other young physicists, Feynman soon fell under the spell of the charismatic Oppenheimer, who telephoned Feynman long distance from Chicago to inform him that he had found a sanatorium in Albuquerque, New Mexico, for Arline. They were among the first to depart for New Mexico, leaving on a train on March 28, 1943. The railroad supplied Arline with a wheelchair, and Feynman paid extra for a private room for her.[55]

At Los Alamos, Feynman was assigned to Hans Bethe's Theoretical (T) Division,[56] and impressed Bethe enough to be made a group leader.[57] He and Bethe developed the Bethe–Feynman formula for calculating the yield of a fission bomb, which built upon previous work by Robert Serber.[58] As a junior physicist, he was not central to the project. He administered the computation group of human computers in the theoretical division. With Stanley Frankel and Nicholas Metropolis, he assisted in establishing a system for using IBM punched cards for computation.[59] He invented a new method of computing logarithms that he later used on the Connection Machine.[60][61] Other work at Los Alamos included calculating neutron equations for the Los Alamos "Water Boiler", a small nuclear reactor, to measure how close an assembly of fissile material was to criticality.[62]

On completing this work, Feynman was sent to the Clinton Engineer Works in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, where the Manhattan Project had its uranium enrichment facilities. He aided the engineers there in devising safety procedures for material storage so that criticality accidents could be avoided, especially when enriched uranium came into contact with water, which acted as a neutron moderator. He insisted on giving the rank and file a lecture on nuclear physics so that they would realize the dangers.[63] He explained that while any amount of unenriched uranium could be safely stored, the enriched uranium had to be carefully handled. He developed a series of safety recommendations for the various grades of enrichments.[64] He was told that if the people at Oak Ridge gave him any difficulty with his proposals, he was to inform them that Los Alamos "could not be responsible for their safety otherwise".[65]

Returning to Los Alamos, Feynman was put in charge of the group responsible for the theoretical work and calculations on the proposed uranium hydride bomb, which ultimately proved to be infeasible.[57][66] He was sought out by physicist Niels Bohr for one-on-one discussions. He later discovered the reason: most of the other physicists were too much in awe of Bohr to argue with him. Feynman had no such inhibitions, vigorously pointing out anything he considered to be flawed in Bohr's thinking. He said he felt as much respect for Bohr as anyone else, but once anyone got him talking about physics, he would become so focused he forgot about social niceties. Perhaps because of this, Bohr never warmed to Feynman.[67][68]

At Los Alamos, which was isolated for security, Feynman amused himself by investigating the combination locks on the cabinets and desks of physicists. He often found that they left the lock combinations on the factory settings, wrote the combinations down, or used easily guessable combinations like dates.[69] He found one cabinet's combination by trying numbers he thought a physicist might use (it proved to be 27–18–28 after the base of natural logarithms, e = 2.71828 ...), and found that the three filing cabinets where a colleague kept research notes all had the same combination. He left notes in the cabinets as a prank, spooking his colleague, Frederic de Hoffmann, into thinking a spy had gained access to them.[70]

Feynman's $380 monthly salary was about half the amount needed for his modest living expenses and Arline's medical bills, and they were forced to dip into her $3,300 in savings.[71] On weekends he drove to Albuquerque to see Arline in a car borrowed from his friend Klaus Fuchs.[72][73] Asked who at Los Alamos was most likely to be a spy, Fuchs mentioned Feynman's safe cracking and frequent trips to Albuquerque;[72] Fuchs himself later confessed to spying for the Soviet Union.[74] The FBI would compile a bulky file on Feynman.[75]

Informed that Arline was dying, Feynman drove to Albuquerque and sat with her for hours until she died on June 16, 1945.[76] He then immersed himself in work on the project and was present at the Trinity nuclear test. Feynman claimed to be the only person to see the explosion without the very dark glasses or welder's lenses provided, reasoning that it was safe to look through a truck windshield, as it would screen out the harmful ultraviolet radiation. The immense brightness of the explosion made him duck to the truck's floor, where he saw a temporary "purple splotch" afterimage.[77]

康乃尔[编辑]

Feynman nominally held an appointment at the University of Wisconsin–Madison as an assistant professor of physics, but was on unpaid leave during his involvement in the Manhattan Project.[78] In 1945, he received a letter from Dean Mark Ingraham of the College of Letters and Science requesting his return to the university to teach in the coming academic year. His appointment was not extended when he did not commit to returning. In a talk given there several years later, Feynman quipped, "It's great to be back at the only university that ever had the good sense to fire me."[79]

As early as October 30, 1943, Bethe had written to the chairman of the physics department of his university, Cornell, to recommend that Feynman be hired. On February 28, 1944, this was endorsed by Robert Bacher,[80] also from Cornell,[81] and one of the most senior scientists at Los Alamos.[82] This led to an offer being made in August 1944, which Feynman accepted. Oppenheimer had also hoped to recruit Feynman to the University of California, but the head of the physics department, Raymond T. Birge, was reluctant. He made Feynman an offer in May 1945, but Feynman turned it down. Cornell matched its salary offer of $3,900 per annum.[80] Feynman became one of the first of the Los Alamos Laboratory's group leaders to depart, leaving for Ithaca, New York, in October 1945.[83]

Because Feynman was no longer working at the Los Alamos Laboratory, he was no longer exempt from the draft. At his induction, physical Army psychiatrists diagnosed Feynman as suffering from a mental illness and the Army gave him a 4-F exemption on mental grounds.[84][85] His father died suddenly on October 8, 1946, and Feynman suffered from depression.[86] On October 17, 1946, he wrote a letter to Arline, expressing his deep love and heartbreak. The letter was sealed and only opened after his death. "Please excuse my not mailing this," the letter concluded, "but I don't know your new address."[87] Unable to focus on research problems, Feynman began tackling physics problems, not for utility, but for self-satisfaction.[86] One of these involved analyzing the physics of a twirling, nutating disk as it is moving through the air, inspired by an incident in the cafeteria at Cornell when someone tossed a dinner plate in the air.[88] He read the work of Sir William Rowan Hamilton on quaternions, and attempted unsuccessfully to use them to formulate a relativistic theory of electrons. His work during this period, which used equations of rotation to express various spinning speeds, ultimately proved important to his Nobel Prize–winning work, yet because he felt burned out and had turned his attention to less immediately practical problems, he was surprised by the offers of professorships from other renowned universities, including the Institute for Advanced Study, the University of California, Los Angeles, and the University of California, Berkeley.[86]

Feynman was not the only frustrated theoretical physicist in the early post-war years. Quantum electrodynamics suffered from infinite integrals in perturbation theory. These were clear mathematical flaws in the theory, which Feynman and Wheeler had unsuccessfully attempted to work around.[89] "Theoreticians", noted Murray Gell-Mann, "were in disgrace."[90] In June 1947, leading American physicists met at the Shelter Island Conference. For Feynman, it was his "first big conference with big men ... I had never gone to one like this one in peacetime."[91] The problems plaguing quantum electrodynamics were discussed, but the theoreticians were completely overshadowed by the achievements of the experimentalists, who reported the discovery of the Lamb shift, the measurement of the magnetic moment of the electron, and Robert Marshak's two-meson hypothesis.[92]

Bethe took the lead from the work of Hans Kramers, and derived a renormalized non-relativistic quantum equation for the Lamb shift. The next step was to create a relativistic version. Feynman thought that he could do this, but when he went back to Bethe with his solution, it did not converge.[93] Feynman carefully worked through the problem again, applying the path integral formulation that he had used in his thesis. Like Bethe, he made the integral finite by applying a cut-off term. The result corresponded to Bethe's version.[94][95] Feynman presented his work to his peers at the Pocono Conference in 1948. It did not go well. Julian Schwinger gave a long presentation of his work in quantum electrodynamics, and Feynman then offered his version, titled "Alternative Formulation of Quantum Electrodynamics". The unfamiliar Feynman diagrams, used for the first time, puzzled the audience. Feynman failed to get his point across, and Paul Dirac, Edward Teller and Niels Bohr all raised objections.[96][97]

To Freeman Dyson, one thing at least was clear: Shin'ichirō Tomonaga, Schwinger and Feynman understood what they were talking about even if no one else did, but had not published anything. He was convinced that Feynman's formulation was easier to understand, and ultimately managed to convince Oppenheimer that this was the case.[98] Dyson published a paper in 1949, which added new rules to Feynman's that told how to implement renormalization.[99] Feynman was prompted to publish his ideas in the Physical Review in a series of papers over three years.[100] His 1948 papers on "A Relativistic Cut-Off for Classical Electrodynamics" attempted to explain what he had been unable to get across at Pocono.[101] His 1949 paper on "The Theory of Positrons" addressed the Schrödinger equation and Dirac equation, and introduced what is now called the Feynman propagator.[102] Finally, in papers on the "Mathematical Formulation of the Quantum Theory of Electromagnetic Interaction" in 1950 and "An Operator Calculus Having Applications in Quantum Electrodynamics" in 1951, he developed the mathematical basis of his ideas, derived familiar formulae and advanced new ones.[103]

While papers by others initially cited Schwinger, papers citing Feynman and employing Feynman diagrams appeared in 1950, and soon became prevalent.[104] Students learned and used the powerful new tool that Feynman had created. Computer programs were later written to compute Feynman diagrams, providing a tool of unprecedented power. It is possible to write such programs because the Feynman diagrams constitute a formal language with a formal grammar. Marc Kac provided the formal proofs of the summation under history, showing that the parabolic partial differential equation can be re-expressed as a sum under different histories (that is, an expectation operator), what is now known as the Feynman–Kac formula, the use of which extends beyond physics to many applications of stochastic processes.[105] To Schwinger, however, the Feynman diagram was "pedagogy, not physics."[106]

By 1949, Feynman was becoming restless at Cornell. He never settled into a particular house or apartment, living in guest houses or student residences, or with married friends "until these arrangements became sexually volatile."[107] He liked to date undergraduates, hire prostitutes, and sleep with the wives of friends.[108] He was not fond of Ithaca's cold winter weather, and pined for a warmer climate.[109] Above all, at Cornell, he was always in the shadow of Hans Bethe.[107] Despite all of this, Feynman looked back favorably on the Telluride House, where he resided for a large period of his Cornell career. In an interview, he described the House as "a group of boys that have been specially selected because of their scholarship, because of their cleverness or whatever it is, to be given free board and lodging and so on, because of their brains." He enjoyed the house's convenience and said that "it's there that I did the fundamental work" for which he won the Nobel Prize.[110][111]

加州理工学院[编辑]

个人与政治生涯[编辑]

Feynman spent several weeks in Rio de Janeiro in July 1949.[112] That year, the Soviet Union detonated its first atomic bomb, generating anti-communist hysteria.[113] Fuchs was arrested as a Soviet spy in 1950 and the FBI questioned Bethe about Feynman's loyalty.[114] Physicist David Bohm was arrested on December 4, 1950[115] and emigrated to Brazil in October 1951.[116] A girlfriend told Feynman that he should also consider moving to South America.[113] He had a sabbatical coming for 1951–52,[117] and elected to spend it in Brazil, where he gave courses at the Centro Brasileiro de Pesquisas Físicas. In Brazil, Feynman was impressed with samba music, and learned to play a metal percussion instrument, the frigideira.[118] He was an enthusiastic amateur player of bongo and conga drums and often played them in the pit orchestra in musicals.[119][120] He spent time in Rio with his friend Bohm but Bohm could not convince Feynman to investigate Bohm's ideas on physics.[121]

Feynman did not return to Cornell. Bacher, who had been instrumental in bringing Feynman to Cornell, had lured him to the California Institute of Technology (Caltech). Part of the deal was that he could spend his first year on sabbatical in Brazil.[122][107] He had become smitten by Mary Louise Bell from Neodesha, Kansas. They had met in a cafeteria in Cornell, where she had studied the history of Mexican art and textiles. She later followed him to Caltech, where he gave a lecture. While he was in Brazil, she taught classes on the history of furniture and interiors at Michigan State University. He proposed to her by mail from Rio de Janeiro, and they married in Boise, Idaho, on June 28, 1952, shortly after he returned. They frequently quarreled and she was frightened by his violent temper. Their politics were different; although he registered and voted as a Republican, she was more conservative, and her opinion on the 1954 Oppenheimer security hearing ("Where there's smoke there's fire") offended him. They separated on May 20, 1956. An interlocutory decree of divorce was entered on June 19, 1956, on the grounds of "extreme cruelty". The divorce became final on May 5, 1958.[123][124]

In the wake of the 1957 Sputnik crisis, the US government's interest in science rose for a time. Feynman was considered for a seat on the President's Science Advisory Committee, but was not appointed. At this time, the FBI interviewed a woman close to Feynman, possibly Mary Lou, who sent a written statement to J. Edgar Hoover on August 8, 1958:

I do not know—but I believe that Richard Feynman is either a Communist or very strongly pro-Communist—and as such is a very definite security risk. This man is, in my opinion, an extremely complex and dangerous person, a very dangerous person to have in a position of public trust ... In matters of intrigue Richard Feynman is, I believe immensely clever—indeed a genius—and he is, I further believe, completely ruthless, unhampered by morals, ethics, or religion—and will stop at absolutely nothing to achieve his ends.[124]

The US government nevertheless sent Feynman to Geneva for the September 1958 Atoms for Peace Conference. On the beach at Lake Geneva, he met Gweneth Howarth, who was from Ripponden, Yorkshire, and working in Switzerland as an au pair. Feynman's love life had been turbulent since his divorce; his previous girlfriend had walked off with his Albert Einstein Award medal and, on the advice of an earlier girlfriend, had feigned pregnancy and blackmailed him into paying for an abortion, then used the money to buy furniture. When Feynman found that Howarth was being paid only $25 a month, he offered her $20 a week to be his live-in maid. Feynman knew that this sort of behavior was illegal under the Mann Act, so he had a friend, Matthew Sands, act as her sponsor. Howarth pointed out that she already had two boyfriends, but decided to take Feynman up on his offer, and arrived in Altadena, California, in June 1959. She made a point of dating other men, but Feynman proposed in early 1960. They were married on September 24, 1960, at the Huntington Hotel in Pasadena. They had a son, Carl, in 1962, and adopted a daughter, Michelle, in 1968.[126][127] Besides their home in Altadena, they had a beach house in Baja California, purchased with the money from Feynman's Nobel Prize.[128]

Feynman tried marijuana and ketamine at John Lilly's famed sensory deprivation tanks, as a way of studying consciousness.[129][130] He gave up alcohol when he began to show vague, early signs of alcoholism, as he did not want to do anything that could damage his brain.[131] Despite his curiosity about hallucinations, he was reluctant to experiment with LSD.[131]

物理[编辑]

At Caltech, Feynman investigated the physics of the superfluidity of supercooled liquid helium, where helium seems to display a complete lack of viscosity when flowing. Feynman provided a quantum-mechanical explanation for the Soviet physicist Lev Landau's theory of superfluidity.[132] Applying the Schrödinger equation to the question showed that the superfluid was displaying quantum mechanical behavior observable on a macroscopic scale. This helped with the problem of superconductivity, but the solution eluded Feynman.[133] It was solved with the BCS theory of superconductivity, proposed by John Bardeen, Leon Neil Cooper, and John Robert Schrieffer in 1957.[132]

Feynman, inspired by a desire to quantize the Wheeler–Feynman absorber theory of electrodynamics, laid the groundwork for the path integral formulation and Feynman diagrams.[45]

With Murray Gell-Mann, Feynman developed a model of weak decay, which showed that the current coupling in the process is a combination of vector and axial currents (an example of weak decay is the decay of a neutron into an electron, a proton, and an antineutrino). Although E. C. George Sudarshan and Robert Marshak developed the theory nearly simultaneously, Feynman's collaboration with Murray Gell-Mann was seen as seminal because the weak interaction was neatly described by the vector and axial currents. It thus combined the 1933 beta decay theory of Enrico Fermi with an explanation of parity violation.[134]

Feynman attempted an explanation, called the parton model, of the strong interactions governing nucleon scattering. The parton model emerged as a complement to the quark model developed by Gell-Mann. The relationship between the two models was murky; Gell-Mann referred to Feynman's partons derisively as "put-ons". In the mid-1960s, physicists believed that quarks were just a bookkeeping device for symmetry numbers, not real particles; the statistics of the omega-minus particle, if it were interpreted as three identical strange quarks bound together, seemed impossible if quarks were real.[135][136]

The SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory deep inelastic scattering experiments of the late 1960s showed that nucleons (protons and neutrons) contained point-like particles that scattered electrons. It was natural to identify these with quarks, but Feynman's parton model attempted to interpret the experimental data in a way that did not introduce additional hypotheses. For example, the data showed that some 45% of the energy momentum was carried by electrically neutral particles in the nucleon. These electrically neutral particles are now seen to be the gluons that carry the forces between the quarks, and their three-valued color quantum number solves the omega-minus problem. Feynman did not dispute the quark model; for example, when the fifth quark was discovered in 1977, Feynman immediately pointed out to his students that the discovery implied the existence of a sixth quark, which was discovered in the decade after his death.[135][137]

After the success of quantum electrodynamics, Feynman turned to quantum gravity. By analogy with the photon, which has spin 1, he investigated the consequences of a free massless spin 2 field and derived the Einstein field equation of general relativity, but little more. The computational device that Feynman discovered then for gravity, "ghosts", which are "particles" in the interior of his diagrams that have the "wrong" connection between spin and statistics, have proved invaluable in explaining the quantum particle behavior of the Yang–Mills theories, for example, quantum chromodynamics and the electro-weak theory.[138] He did work on all four of the forces of nature: electromagnetic, the weak force, the strong force and gravity. John and Mary Gribbin state in their book on Feynman that "Nobody else has made such influential contributions to the investigation of all four of the interactions".[139]

Partly as a way to bring publicity to progress in physics, Feynman offered $1,000 prizes for two of his challenges in nanotechnology; one was claimed by William McLellan and the other by Tom Newman.[140]

Feynman was also interested in the relationship between physics and computation. He was also one of the first scientists to conceive the possibility of quantum computers.[141][142] In the 1980's he began to spend his summers work at Thinking Machines Corporation, helping to build some of the first parallel supercomputers and considering the construction of quantum computers.[143][144] In 1984–1986, he developed a variational method for the approximate calculation of path integrals, which has led to a powerful method of converting divergent perturbation expansions into convergent strong-coupling expansions (variational perturbation theory) and, as a consequence, to the most accurate determination[145] of critical exponents measured in satellite experiments.[146]

教育[编辑]

In the early 1960s, Feynman acceded to a request to "spruce up" the teaching of undergraduates at Caltech. After three years devoted to the task, he produced a series of lectures that later became The Feynman Lectures on Physics. He wanted a picture of a drumhead sprinkled with powder to show the modes of vibration at the beginning of the book. Concerned over the connections to drugs and rock and roll that could be made from the image, the publishers changed the cover to plain red, though they included a picture of him playing drums in the foreword. The Feynman Lectures on Physics occupied two physicists, Robert B. Leighton and Matthew Sands, as part-time co-authors for several years. Even though the books were not adopted by universities as textbooks, they continue to sell well because they provide a deep understanding of physics.[147] Many of his lectures and miscellaneous talks were turned into other books, including The Character of Physical Law, QED: The Strange Theory of Light and Matter, Statistical Mechanics, Lectures on Gravitation, and the Feynman Lectures on Computation.[148]

Feynman wrote about his experiences teaching physics undergraduates in Brazil. The students' study habits and the Portuguese language textbooks were so devoid of any context or applications for their information that, in Feynman's opinion, the students were not learning physics at all. At the end of the year, Feynman was invited to give a lecture on his teaching experiences, and he agreed to do so, provided he could speak frankly, which he did.[149][150] Feynman opposed rote learning or unthinking memorization and other teaching methods that emphasized form over function. Clear thinking and clear presentation were fundamental prerequisites for his attention. It could be perilous even to approach him unprepared, and he did not forget fools and pretenders.[151] In 1964, he served on the California State Curriculum Commission, which was responsible for approving textbooks to be used by schools in California. He was not impressed with what he found.[152] Many of the mathematics texts covered subjects of use only to pure mathematicians as part of the "New Math". Elementary students were taught about sets, but:

It will perhaps surprise most people who have studied these textbooks to discover that the symbol ∪ or ∩ representing union and intersection of sets and the special use of the brackets { } and so forth, all the elaborate notation for sets that is given in these books, almost never appear in any writings in theoretical physics, in engineering, in business arithmetic, computer design, or other places where mathematics is being used. I see no need or reason for this all to be explained or to be taught in school. It is not a useful way to express one's self. It is not a cogent and simple way. It is claimed to be precise, but precise for what purpose?[153]

In April 1966, Feynman delivered an address to the National Science Teachers Association, in which he suggested how students could be made to think like scientists, be open-minded, curious, and especially, to doubt. In the course of the lecture, he gave a definition of science, which he said came about by several stages. The evolution of intelligent life on planet Earth—creatures such as cats that play and learn from experience. The evolution of humans, who came to use language to pass knowledge from one individual to the next, so that the knowledge was not lost when an individual died. Unfortunately, incorrect knowledge could be passed down as well as correct knowledge, so another step was needed. Galileo and others started doubting the truth of what was passed down and to investigate ab initio, from experience, what the true situation was—this was science.[154]

In 1974, Feynman delivered the Caltech commencement address on the topic of cargo cult science, which has the semblance of science, but is only pseudoscience due to a lack of "a kind of scientific integrity, a principle of scientific thought that corresponds to a kind of utter honesty" on the part of the scientist. He instructed the graduating class that "The first principle is that you must not fool yourself—and you are the easiest person to fool. So you have to be very careful about that. After you've not fooled yourself, it's easy not to fool other scientists. You just have to be honest in a conventional way after that."[155]

Feynman served as doctoral advisor to 31 students.[156]

In 1977, Feynman supported his colleague Jenijoy La Belle, who had been hired as Caltech's first female professor in 1969, and filed suit with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission after she was refused tenure in 1974. The EEOC ruled against Caltech in 1977, adding that La Belle had been paid less than male colleagues. La Belle finally received tenure in 1979. Many of Feynman's colleagues were surprised that he took her side. He had got to know La Belle and both liked and admired her.[157][158]

《别闹了,费曼先生!》[编辑]

In the 1960s, Feynman began thinking of writing an autobiography, and he began granting interviews to historians. In the 1980s, working with Ralph Leighton (Robert Leighton's son), he recorded chapters on audio tape that Ralph transcribed. The book was published in 1985 as Surely You're Joking, Mr. Feynman! and became a best-seller.

Gell-Mann was upset by Feynman's account in the book of the weak interaction work, and threatened to sue, resulting in a correction being inserted in later editions.[159] This incident was just the latest provocation in decades of bad feeling between the two scientists. Gell-Mann often expressed frustration at the attention Feynman received;[160] he remarked: "[Feynman] was a great scientist, but he spent a great deal of his effort generating anecdotes about himself."[161]

The publication of the book brought a new wave of criticism about Feynman's attitude toward women. There had been protests over his alleged sexism in 1968, and again in 1972.[157][162] Feynman received heavy criticism for the attitudes toward women expressed in this book, for example for calling women "bitches" for not sleeping with him, or telling a woman she was "worse than a whore" because he had bought her a sandwich and she did not reciprocate with sexual favors.[163][164][165][166][167][168][169]

挑战者号灾难[编辑]

When invited to join the Rogers Commission, which investigated the Challenger disaster, Feynman was hesitant. The nation’s capital, he told his wife, was “a great big world of mystery to me, with tremendous forces.”[170] But she convinced him to go, saying he might discover something others overlooked. Because Feynman did not balk at blaming NASA for the disaster, he clashed with the politically savvy commission chairman William Rogers, a former Secretary of State. During a break in one hearing, Rogers told commission member Neil Armstrong, "Feynman is becoming a pain in the ass."[171] During a televised hearing, Feynman demonstrated that the material used in the shuttle's O-rings became less resilient in cold weather by compressing a sample of the material in a clamp and immersing it in ice-cold water.[172] The commission ultimately determined that the disaster was caused by the primary O-ring not properly sealing in unusually cold weather at Cape Canaveral.[173]

Feynman devoted the latter half of his book What Do You Care What Other People Think? to his experience on the Rogers Commission, straying from his usual convention of brief, light-hearted anecdotes to deliver an extended and sober narrative. Feynman's account reveals a disconnect between NASA's engineers and executives that was far more striking than he expected. His interviews of NASA's high-ranking managers revealed startling misunderstandings of elementary concepts. For instance, NASA managers claimed that there was a 1 in 100,000 chance of a catastrophic failure aboard the Shuttle, but Feynman discovered that NASA's own engineers estimated the chance of a catastrophe at closer to 1 in 200. He concluded that NASA management's estimate of the reliability of the Space Shuttle was unrealistic, and he was particularly angered that NASA used it to recruit Christa McAuliffe into the Teacher-in-Space program. He warned in his appendix to the commission's report (which was included only after he threatened not to sign the report), "For a successful technology, reality must take precedence over public relations, for nature cannot be fooled."[174]

荣誉[编辑]

The first public recognition of Feynman's work came in 1954, when Lewis Strauss, the chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) notified him that he had won the Albert Einstein Award, which was worth $15,000 and came with a gold medal. Because of Strauss's actions in stripping Oppenheimer of his security clearance, Feynman was reluctant to accept the award, but Isidor Isaac Rabi cautioned him: "You should never turn a man's generosity as a sword against him. Any virtue that a man has, even if he has many vices, should not be used as a tool against him."[175] It was followed by the AEC's Ernest Orlando Lawrence Award in 1962.[176] Schwinger, Tomonaga and Feynman shared the 1965 Nobel Prize in Physics "for their fundamental work in quantum electrodynamics, with deep-ploughing consequences for the physics of elementary particles".[177] He was elected a Foreign Member of the Royal Society in 1965,[6][178] received the Oersted Medal in 1972,[179] and the National Medal of Science in 1979.[180] He was elected a Member of the National Academy of Sciences, but ultimately resigned[181][182] and is no longer listed by them.[183]

逝世[编辑]

In 1978, Feynman sought medical treatment for abdominal pains and was diagnosed with liposarcoma, a rare form of cancer. Surgeons removed a tumor the size of a football that had crushed one kidney and his spleen. Further operations were performed in October 1986 and October 1987.[184] He was again hospitalized at the UCLA Medical Center on February 3, 1988. A ruptured duodenal ulcer caused kidney failure, and he declined to undergo the dialysis that might have prolonged his life for a few months. Watched over by his wife Gweneth, sister Joan, and cousin Frances Lewine, he died on February 15, 1988, at age 69.[185]

When Feynman was nearing death, he asked Danny Hillis why he was so sad. Hillis replied that he thought Feynman was going to die soon. Feynman said that this sometimes bothered him, too, adding, when you get to be as old as he was, and have told so many stories to so many people, even when he was dead he would not be completely gone.[186]

Near the end of his life, Feynman attempted to visit the Tuvan Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (ASSR) in Russia, a dream thwarted by Cold War bureaucratic issues. The letter from the Soviet government authorizing the trip was not received until the day after he died. His daughter Michelle later made the journey.[187]

His burial was at Mountain View Cemetery and Mausoleum in Altadena, California.[188] His last words were: "I'd hate to die twice. It's so boring."[187]

影响[编辑]

Aspects of Feynman's life have been portrayed in various media. Feynman was portrayed by Matthew Broderick in the 1996 biopic Infinity.[189] Actor Alan Alda commissioned playwright Peter Parnell to write a two-character play about a fictional day in the life of Feynman set two years before Feynman's death. The play, QED, premiered at the Mark Taper Forum in Los Angeles in 2001 and was later presented at the Vivian Beaumont Theater on Broadway, with both presentations starring Alda as Richard Feynman.[190] Real Time Opera premiered its opera Feynman at the Norfolk (CT) Chamber Music Festival in June 2005.[191] In 2011, Feynman was the subject of a biographical graphic novel entitled simply Feynman, written by Jim Ottaviani and illustrated by Leland Myrick.[192] In 2013, Feynman's role on the Rogers Commission was dramatised by the BBC in The Challenger (US title: The Challenger Disaster), with William Hurt playing Feynman.[193][194][195] In the 2016 book, Idea Makers: Personal Perspectives on the Lives & Ideas of Some Notable People, it states that one of the things Feynman often said was that "peace of mind is the most important prerequisite for creative work." Feynman felt one should do everything possible to achieve that peace of mind.[196]

Feynman is commemorated in various ways. On May 4, 2005, the United States Postal Service issued the "American Scientists" commemorative set of four 37-cent self-adhesive stamps in several configurations. The scientists depicted were Richard Feynman, John von Neumann, Barbara McClintock, and Josiah Willard Gibbs. Feynman's stamp, sepia-toned, features a photograph of a 30-something Feynman and eight small Feynman diagrams.[197] The stamps were designed by Victor Stabin under the artistic direction of Carl T. Herrman.[198] The main building for the Computing Division at Fermilab is named the "Feynman Computing Center" in his honor.[199] A photograph of Richard Feynman giving a lecture was part of the 1997 poster series commissioned by Apple Inc. for their "Think Different" advertising campaign.[200] The Sheldon Cooper character in The Big Bang Theory is a Feynman fan who emulates him by playing the bongo drums.[201] On January 27, 2016, Bill Gates wrote an article "The Best Teacher I Never Had" describing Feynman's talents as a teacher which inspired Gates to create Project Tuva to place the videos of Feynman's Messenger Lectures, The Character of Physical Law, on a website for public viewing. In 2015 Gates made a video on why he thought Feynman was special. The video was made for the 50th anniversary of Feynman's 1965 Nobel Prize, in response to Caltech's request for thoughts on Feynman.[202]

著作[编辑]

科学作品[编辑]

- Feynman, Richard P. Laurie M. Brown , 编. The Principle of Least Action in Quantum Mechanics. PhD Dissertation, Princeton University. World Scientific (with title "Feynman's Thesis: a New Approach to Quantum Theory"). 19422005. ISBN 978-981-256-380-4.

- Wheeler, John A.; Feynman, Richard P. Interaction with the Absorber as the Mechanism of Radiation. Reviews of Modern Physics. 1945, 17 (2–3): 157–181. Bibcode:1945RvMP...17..157W. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.17.157.

- Feynman, Richard P. A Theorem and its Application to Finite Tampers. Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory, Atomic Energy Commission. 1946. OSTI 4341197. doi:10.2172/4341197.

- Feynman, Richard P.; Welton, T. A. Neutron Diffusion in a Space Lattice of Fissionable and Absorbing Materials. Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory, Atomic Energy Commission. 1946. OSTI 4381097. doi:10.2172/4381097.

- Feynman, Richard P.; Metropolis, N.; Teller, E. Equations of State of Elements Based on the Generalized Fermi-Thomas Theory (PDF). Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory, Atomic Energy Commission. 1947. OSTI 4417654. doi:10.2172/4417654.

- Feynman, Richard P. Space-time approach to non-relativistic quantum mechanics. Reviews of Modern Physics. 1948, 20 (2): 367–387. Bibcode:1948RvMP...20..367F. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.20.367.

- Feynman, Richard P. A Relativistic Cut-Off for Classical Electrodynamics. Physical Review. 1948, 74 (8): 939–946. Bibcode:1948PhRv...74..939F. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.74.939.

- Feynman, Richard P. Relativistic Cut-Off for Quantum Electrodynamics. Physical Review. 1948, 74 (10): 1430–1438. Bibcode:1948PhRv...74.1430F. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.74.1430.

- Wheeler, John A.; Feynman, Richard P. Classical Electrodynamics in Terms of Direct Interparticle Action (PDF). Reviews of Modern Physics. 1949, 21 (3): 425–433. Bibcode:1949RvMP...21..425W. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.21.425.

- Feynman, Richard P. The theory of positrons. Physical Review. 1949, 76 (6): 749–759. Bibcode:1949PhRv...76..749F. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.76.749.

- Feynman, Richard P. Space-Time Approach to Quantum Electrodynamic. Physical Review. 1949, 76 (6): 769–789. Bibcode:1949PhRv...76..769F. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.76.769.

- Feynman, Richard P. Mathematical formulation of the quantum theory of electromagnetic interaction. Physical Review. 1950, 80 (3): 440–457. Bibcode:1950PhRv...80..440F. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.80.440.

- Feynman, Richard P. An Operator Calculus Having Applications in Quantum Electrodynamics. Physical Review. 1951, 84 (1): 108–128. Bibcode:1951PhRv...84..108F. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.84.108.

- Feynman, Richard P. The λ-Transition in Liquid Helium. Physical Review. 1953, 90 (6): 1116–1117. Bibcode:1953PhRv...90.1116F. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.90.1116.2.

- Feynman, Richard P.; de Hoffmann, F.; Serber, R. Dispersion of the Neutron Emission in U235 Fission. Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory, Atomic Energy Commission. 1955. OSTI 4354998. doi:10.2172/4354998.

- Feynman, Richard P. Science and the Open Channel. Science. 1956, 123 (3191): 307February 24, 1956. Bibcode:1956Sci...123..307F. PMID 17774518. doi:10.1126/science.123.3191.307.

- Cohen, M.; Feynman, Richard P. Theory of Inelastic Scattering of Cold Neutrons from Liquid Helium. Physical Review. 1957, 107 (1): 13–24. Bibcode:1957PhRv..107...13C. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.107.13.

- Feynman, Richard P.; Vernon, F. L.; Hellwarth, R. W. Geometric representation of the Schrödinger equation for solving maser equations (PDF). J. Appl. Phys. 1957, 28 (1): 49. Bibcode:1957JAP....28...49F. doi:10.1063/1.1722572.

- Feynman, Richard P. Plenty of Room at the Bottom. Presentation to American Physical Society. 1959. (原始内容存档于February 11, 2010). 已忽略未知参数

|df=(帮助) - Edgar, R. S.; Feynman, Richard P.; Klein, S.; Lielausis, I.; Steinberg, C. M. Mapping experiments with r mutants of bacteriophage T4D. Genetics. 1962, 47 (2): 179–86February 1962. PMC 1210321

. PMID 13889186.

. PMID 13889186. - Feynman, Richard P. What is Science? (PDF). The Physics Teacher. 1968, 7 (6): 313–320 [1966] [December 15, 2016]. Bibcode:1969PhTea...7..313F. doi:10.1119/1.2351388. Lecture presented at the fifteenth annual meeting of the National Science Teachers Association, 1966 in New York City

- Feynman, Richard P. The Development of the Space-Time View of Quantum Electrodynamics. Science. 1966, 153 (3737): 699–708August 12, 1966. Bibcode:1966Sci...153..699F. PMID 17791121. doi:10.1126/science.153.3737.699.

- Feynman, Richard P. Structure of the proton. Science (American Association for the Advancement of Science). 1974a, 183 (4125): 601–610February 15, 1974. Bibcode:1974Sci...183..601F. JSTOR 1737688. PMID 17778830. doi:10.1126/science.183.4125.601.

- Feynman, Richard P. Cargo Cult Science (PDF). Engineering and Science. 1974, 37 (7).

- Feynman, Richard P.; Kleinert, Hagen. Effective classical partition functions (PDF). Physical Review A. 1986, 34 (6): 5080–5084December 1986. Bibcode:1986PhRvA..34.5080F. PMID 9897894. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.34.5080.

- Feynman, Richard P. Rogers Commission Report, Volume 2 Appendix F – Personal Observations on Reliability of Shuttle. NASA. 1986.

- Feynman, Richard P. Laurie M. Brown , 编. Selected Papers of Richard Feynman: With Commentary. 20th Century Physics. World Scientific. 2000. ISBN 978-981-02-4131-5.

教科书和讲座笔记[编辑]

The Feynman Lectures on Physics is perhaps his most accessible work for anyone with an interest in physics, compiled from lectures to Caltech undergraduates in 1961–1964. As news of the lectures' lucidity grew, professional physicists and graduate students began to drop in to listen. Co-authors Robert B. Leighton and Matthew Sands, colleagues of Feynman, edited and illustrated them into book form. The work has endured and is useful to this day. They were edited and supplemented in 2005 with Feynman's Tips on Physics: A Problem-Solving Supplement to the Feynman Lectures on Physics by Michael Gottlieb and Ralph Leighton (Robert Leighton's son), with support from Kip Thorne and other physicists.

- Feynman, Richard P.; Leighton, Robert B.; Sands, Matthew. The Feynman Lectures on Physics: The Definitive and Extended Edition 2nd. Addison Wesley. 2005 [1970]. ISBN 0-8053-9045-6. Includes Feynman's Tips on Physics (with Michael Gottlieb and Ralph Leighton), which includes four previously unreleased lectures on problem solving, exercises by Robert Leighton and Rochus Vogt, and a historical essay by Matthew Sands. Three volumes; originally published as separate volumes in 1964 and 1966.

- Feynman, Richard P. Theory of Fundamental Processes. Addison Wesley. 1961. ISBN 0-8053-2507-7.

- Feynman, Richard P. Quantum Electrodynamics. Addison Wesley. 1962. ISBN 978-0-8053-2501-0.

- Feynman, Richard P.; Hibbs, Albert. Quantum Mechanics and Path Integrals. McGraw Hill. 1965. ISBN 0-07-020650-3.

- Feynman, Richard P. The Character of Physical Law: The 1964 Messenger Lectures. MIT Press. 1967. ISBN 0-262-56003-8.

- Feynman, Richard P. Statistical Mechanics: A Set of Lectures. Reading, Mass: W. A. Benjamin. 1972. ISBN 0-8053-2509-3.

- Feynman, Richard P. QED: The Strange Theory of Light and Matter. Princeton University Press. 1985b. ISBN 0-691-02417-0.

- Feynman, Richard P. Elementary Particles and the Laws of Physics: The 1986 Dirac Memorial Lectures. Cambridge University Press. 1987. ISBN 0-521-34000-4.

- Feynman, Richard P. Brian Hatfield , 编. Lectures on Gravitation. Addison Wesley Longman. 1995. ISBN 0-201-62734-5.

- Feynman, Richard P. Feynman's Lost Lecture: The Motion of Planets Around the Sun Vintage Press. London: Vintage. 1997. ISBN 0-09-973621-7.

- Feynman, Richard P. Tony Hey and Robin W. Allen , 编. Feynman Lectures on Computation. Perseus Books Group. 2000. ISBN 0-7382-0296-7.

其他知名著作[编辑]

- Feynman, Richard P. Ralph Leighton , 编. Surely You're Joking, Mr. Feynman!: Adventures of a Curious Character. W. W. Norton & Co. 1985. ISBN 0-393-01921-7. OCLC 10925248.

- Feynman, Richard P. Ralph Leighton , 编. What Do You Care What Other People Think?: Further Adventures of a Curious Character. W. W. Norton & Co. 1988. ISBN 0-393-02659-0.

- No Ordinary Genius: The Illustrated Richard Feynman, ed. Christopher Sykes, W. W. Norton & Co, 1996, ISBN 0-393-31393-X.

- Six Easy Pieces: Essentials of Physics Explained by Its Most Brilliant Teacher, Perseus Books, 1994, ISBN 0-201-40955-0. Listed by the Board of Directors of the Modern Library as one of the 100 best nonfiction books.[203]

- Six Not So Easy Pieces: Einstein's Relativity, Symmetry and Space-Time, Addison Wesley, 1997, ISBN 0-201-15026-3.

- Feynman, Richard P. The Meaning of It All: Thoughts of a Citizen Scientist. Reading, Massachusetts: Perseus Publishing. 1998. ISBN 0-7382-0166-9.

- Feynman, Richard P. Robbins, Jeffrey , 编. The Pleasure of Finding Things Out: The Best Short Works of Richard P. Feynman. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Perseus Books. 1999. ISBN 0-7382-0108-1.

- Classic Feynman: All the Adventures of a Curious Character, edited by Ralph Leighton, W. W. Norton & Co, 2005, ISBN 0-393-06132-9. Chronologically reordered omnibus volume of Surely You're Joking, Mr. Feynman! and What Do You Care What Other People Think?, with a bundled CD containing one of Feynman's signature lectures.

音讯和影像纪录[编辑]

- Safecracker Suite (a collection of drum pieces interspersed with Feynman telling anecdotes)

- Los Alamos From Below (audio, talk given by Feynman at Santa Barbara on February 6, 1975)

- Six Easy Pieces (original lectures upon which the book is based)

- Six Not So Easy Pieces (original lectures upon which the book is based)

- The Feynman Lectures on Physics: The Complete Audio Collection

- Samples of Feynman's drumming, chanting and speech are included in the songs "Tuva Groove (Bolur Daa-Bol, Bolbas Daa-Bol)" and "Kargyraa Rap (Dürgen Chugaa)" on the album Back Tuva Future, The Adventure Continues by Kongar-ool Ondar. The hidden track on this album also includes excerpts from lectures without musical background.

- The Messenger Lectures, given at Cornell in 1964, in which he explains basic topics in physics. Available on Project Tuva free.[204] (See also the book The Character of Physical Law)

- Take the world from another point of view [videorecording] / with Richard Feynman; Films for the Hu (1972)

- The Douglas Robb Memorial Lectures, four public lectures of which the four chapters of the book QED: The Strange Theory of Light and Matter are transcripts. (1979)

- The Pleasure of Finding Things Out, BBC Horizon episode (1981) (not to be confused with the later published book of the same title)

- Richard Feynman: Fun to Imagine Collection, BBC Archive of six short films of Feynman talking in a style that is accessible to all about the physics behind common to all experiences. (1983)

- Elementary Particles and the Laws of Physics (1986)

- Tiny Machines: The Feynman Talk on Nanotechnology (video, 1984)

- Computers From the Inside Out (video)

- Quantum Mechanical View of Reality: Workshop at Esalen (video, 1983)

- Idiosyncratic Thinking Workshop (video, 1985)

- Bits and Pieces—From Richard's Life and Times (video, 1988)

- Strangeness Minus Three (video, BBC Horizon 1964)

- No Ordinary Genius (video, Cristopher Sykes Documentary)

- Richard Feynman—The Best Mind Since Einstein (video, Documentary)

- The Motion of Planets Around the Sun (audio, sometimes titled "Feynman's Lost Lecture")

- Nature of Matter (audio)[205]

参见[编辑]

Articles[编辑]

- Physics Today, American Institute of Physics magazine, February 1989 Issue. (Vol. 42, No. 2.) Special Feynman memorial issue containing non-technical articles on Feynman's life and work in physics.

Books[编辑]

- Brown, Laurie M. and Rigden, John S. (editors) (1993) Most of the Good Stuff: Memories of Richard Feynman Simon & Schuster, New York, ISBN 0-88318-870-8. Commentary by Joan Feynman, John Wheeler, Hans Bethe, Julian Schwinger, Murray Gell-Mann, Daniel Hillis, David Goodstein, Freeman Dyson, and Laurie Brown

- Dyson, Freeman (1979) Disturbing the Universe. Harper and Row. ISBN 0-06-011108-9. Dyson's autobiography. The chapters "A Scientific Apprenticeship" and "A Ride to Albuquerque" describe his impressions of Feynman in the period 1947–48 when Dyson was a graduate student at Cornell

- Feynman, Michelle (编). Perfectly Reasonable Deviations from the Beaten Track: The Letters of Richard P. Feynman. Basic Books. 2005. ISBN 0-7382-0636-9. (Published in the UK under the title: Don't You Have Time to Think?, with additional commentary by Michelle Feynman, Allen Lane, 2005, ISBN 0-7139-9847-4.)

- Krauss, Lawrence M. Quantum Man: Richard Feynman's Life in Science. W. W. Norton & Company. 2011. ISBN 978-0-393-06471-1. OCLC 601108916.

- Leighton, Ralph. Tuva or Bust!: Richard Feynman's last journey. W. W. Norton & Company. 2000. ISBN 0-393-32069-3.

- LeVine, Harry. The Great Explainer: The Story of Richard Feynman. Greensboro, North Carolina: Morgan Reynolds. 2009. ISBN 978-1-59935-113-1.; for high school readers

- Milburn, Gerald J. The Feynman Processor: Quantum Entanglement and the Computing Revolution. Reading, Massachusetts: Perseus Books. 1998. ISBN 0-7382-0173-1.

- Mlodinow, Leonard. Feynman's Rainbow: A Search For Beauty In Physics And In Life. New York: Warner Books. 2003. ISBN 0-446-69251-4. Published in the United Kingdom as Some Time With Feynman

- Ottaviani, Jim; Myrick, Leland. Feynman: The Graphic Novel. New York: First Second. 2011. ISBN 978-1-59643-259-8. OCLC 664838951.

Films and plays[编辑]

- Infinity, a movie both directed by and starring Matthew Broderick as Feynman, depicting his love affair with his first wife and ending with the Trinity test. 1996.

- Parnell, Peter (2002), QED, Applause Books, ISBN 978-1-55783-592-5 (play).

- Whittell, Crispin (2006), Clever Dick, Oberon Books, (play)

- "The Quest for Tannu Tuva", with Richard Feynman and Ralph Leighton. 1987, BBC Horizon and PBS Nova (entitled "Last Journey of a Genius").

- No Ordinary Genius, a two-part documentary about Feynman's life and work, with contributions from colleagues, friends and family. 1993, BBC Horizon and PBS Nova (a one-hour version, under the title The Best Mind Since Einstein) (2 × 50-minute films)

- The Challenger (2013), a BBC Two factual drama starring William Hurt, tells the story of American Nobel prize-winning physicist Richard Feynman's determination to reveal the truth behind the 1986 Space Shuttle Challenger disaster.

- The Fantastic Mr Feynman. One hour documentary. 2013, BBC TV.

- How We Built The Bomb (film), a docudrama about The Manhattan Project at Los Alamos. Feynman is played by actor/playwright Michael Raver. 2015.

参考资料[编辑]

- ^ "Everybody called him Dick." - Freeman Dyson

Quote from June 1998 interview with Silvan "Sam" Schweber, posted at webofstories.com on Jan 24, 2008 (view on YouTube) - ^

维基语录上有关Richard_Feynman#Quotes的语录

维基语录上有关Richard_Feynman#Quotes的语录

A collection of quotes from his friends and colleagues Freeman Dyson, Murray Gell-Mann, etc, calling him by the name Dick Feynman, including article title in Feb 1989 Physics Today issue (Vol42 No2) dedicated to Feynman: "Dick Feynman—The Guy in the Office Down the Hall". - ^ Frankie Evans on Feynman, by Frankie Evans (cocktail waitress at local strip club Feynman frequented)

Quote:

"...Dick and I became friends."

One of seven times she refers to him as Dick, never once calling him "Richard". - ^ "Dick... He was my friend. I did call him Dick." - physicist Leonard Susskind

Jan 2011 TED Talk (posted to YouTube on May 16), repeatedly referring to his close friend and college as Dick Feynman.

(Susskind is much more prolific in referring to his friend by his nickname Dick in the Feynman100 birth centennial talk at CalTech, May 11, 2018, "Dick's Tricks", posted to YouTube on May 22.) - ^ Tindol, Robert. Physics World poll names Richard Feynman one of 10 greatest physicists of all time (新闻稿). California Institute of Technology. December 2, 1999 [December 1, 2012]. (原始内容存档于March 21, 2012).

- ^ 6.0 6.1 Richard P. Feynman – Biographical. The Nobel Foundation. [April 23, 2013].

- ^ 7.0 7.1 7.2 J. J. O'Connor; E. F. Robertson. Richard Phillips Feynman. University of St. Andrews. August 2002 [April 23, 2013].

- ^ Oakes 2007,第231页.

- ^ Richard Phillips Feynman. Timeline of Nobel Prize Winners. [April 23, 2013].

- ^ Chown 1985,第34页.

- ^ Close 2011,第58页.

- ^ 12.0 12.1 Sykes 1994,第54页.

- ^ Friedman 2004,第231页.

- ^ Henderson 2011,第8页.

- ^ Gleick 1992,第25–26页.

- ^ Hirshberg, Charles. My Mother, the Scientist. Popular Science. May 2002 [April 23, 2013]. (原始内容存档于June 20, 2016) –通过www.aas.org. 已忽略未知参数

|df=(帮助) - ^ Feynman 1988,第25页.

- ^ Harrison, John. Physics, bongos and the art of the nude. The Daily Telegraph. [April 23, 2013].

- ^ Feynman 1985,第284–287页.

- ^ Schwach, Howard. Museum Tracks Down FRHS Nobel Laureates. The Wave. April 15, 2005 [April 23, 2013].

- ^ Gleick 1992,第30页.

- ^ Carroll 1996,第9页: "The general experience of psychologists in applying tests would lead them to expect that Feynman would have made a much higher IQ if he had been properly tested."

- ^ Gribbin & Gribbin 1997,第19–20页: Gleick says his IQ was 125; No Ordinary Genius says 123

- ^ Jonathan Wai. A Polymath Physicist On Richard Feynman's "Low" IQ And Finding Another Einstein: A conversation with Steve Hsu. Psychology Today. December 26, 2011 [January 6, 2017].

- ^ Schweber 1994,第374页.

- ^ Richard Feynman – Biography. Atomic Archive. [July 12, 2016].

- ^ Feynman 1985,第24页.

- ^ Gleick 1992,第15页.

- ^ 29.0 29.1 Mehra 1994,第41页.

- ^ Feynman 1985,第72页.

- ^ Gribbin & Gribbin 1997,第45–46页.

- ^ Feynman, Richard. Richard Feynman – Session II. 访谈 with Charles Weiner. American Institute of Physics. March 5, 1966 [May 25, 2017].

- ^ Vallarta, M. S. and Feynman, R. P. The Scattering of Cosmic Rays by the Stars of a Galaxy. Physical Review (American Physical Society). March 1939, 55 (5): 506–507. Bibcode:1939PhRv...55..506V. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.55.506.2.

- ^ Gleick 1992,第82页.

- ^ Feynman, R. P. Forces in Molecules. Physical Review (American Physical Society). August 1939, 56 (4): 340–343. Bibcode:1939PhRv...56..340F. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.56.340.

- ^ Mehra 1994,第71–78页.

- ^ Gribbin & Gribbin 1997,第56页.

- ^ Putnam Competition Individual and Team Winners. Mathematical Association of America. [March 8, 2014].

- ^ 39.0 39.1 Gleick 1992,第84页.

- ^ Feynman 1985,第77–80页.

- ^ Cosmology: Math Plus Mach Equals Far-Out Gravity. Time. June 26, 1964 [August 7, 2010].

- ^ F. Hoyle; J. V. Narlikar. A New Theory of Gravitation. Proceedings of the Royal Society A. 1964, 282 (1389): 191–207. Bibcode:1964RSPSA.282..191H. doi:10.1098/rspa.1964.0227.

- ^ 43.0 43.1 Gleick 1992,第129–130页.

- ^ Feynman, Richard P. The Principle of Least Action in Quantum Mechanics (PDF) (学位论文). Princeton University. 1942 [July 12, 2016].

- ^ 45.0 45.1 45.2 Mehra 1994,第92–101页.

- ^ Gribbin & Gribbin 1997,第66–67页.

- ^ Gleick 1992,第150–151页.

- ^ Gribbin & Gribbin 1997,第63–64页.

- ^ Feynman 1985,第99–103页.

- ^ Gribbin & Gribbin 1997,第64–65页.

- ^ Feynman 1985,第107–108页.

- ^ Richard Feynman Lecture -- "Los Alamos From Below", talk given at UCSB in 1975 (posted to YouTube on Jul 12, 2016)

Quote:

"I did not even have my degree when I started to work on stuff associated with the Manhattan Project."

Later in this same talk, at 5m34s, he explains that he took a six week vacation to finish his thesis so received his PhD prior to his arrival at Los Alamos. - ^ Gleick 1992,第141–145页.

- ^ Hoddeson et al. 1993,第59页.

- ^ Gleick 1992,第158–160页.

- ^ Gleick 1992,第165–169页.

- ^ 57.0 57.1 Hoddeson et al. 1993,第157–159页.

- ^ Hoddeson et al. 1993,第183页.

- ^ Bashe et al. 1986,第14页.

- ^ Hillis 1989,第78页.

- ^ Feynman 1985,第125–129页.

- ^ Galison 1998,第403–407页.

- ^ Galison 1998,第407–409页.

- ^ Wellerstein, Alex. Feynman and the Bomb. Restricted Data. June 6, 2014 [December 4, 2016].

- ^ Feynman 1985,第122页.

- ^ Galison 1998,第414–422页.

- ^ Gleick 1992,第257页.

- ^ Gribbin & Gribbin 1997,第95–96页.

- ^ Gleick 1992,第188–189页.

- ^ Feynman 1985,第147–149页.

- ^ Gribbin & Gribbin 1997,第99页.

- ^ 72.0 72.1 Gleick 1992,第184页.

- ^ Gribbin & Gribbin 1997,第96页.

- ^ Gleick 1992,第296–297页.

- ^ Michael Morisy; Robert Hovden. J Pat Brown , 编. The Feynman Files: The professor's invitation past the Iron Curtain. MuckRock. June 6, 2012 [July 13, 2016].

- ^ Gleick 1992,第200–202页.

- ^ Feynman 1985,第134页.

- ^ Gribbin & Gribbin 1997,第101页.

- ^ Robert H. March. Physics at the University of Wisconsin: A History. Physics in Perspective. 2003, 5 (2): 130–149. Bibcode:2003PhP.....5..130M. doi:10.1007/s00016-003-0142-6.

- ^ 80.0 80.1 Mehra 1994,第161–164, 178–179页.

- ^ Hoddeson et al. 1993,第47–52页.

- ^ Hoddeson et al. 1993,第316页.

- ^ Gleick 1992,第205页.

- ^ Gleick 1992,第225页.

- ^ Feynman 1985,第162–163页.

- ^ 86.0 86.1 86.2 Mehra 1994,第171–174页.

- ^ I love my wife. My wife is dead. Letters of Note. February 15, 2012 [April 23, 2013].

- ^ Gleick 1992,第227–229页.

- ^ Mehra 1994,第213–214页.

- ^ Gleick 1992,第232页.

- ^ Mehra 1994,第217页.

- ^ Mehra 1994,第218–219页.

- ^ Mehra 1994,第223–228页.

- ^ Mehra 1994,第229–234页.

- ^ Richard P. Feynman – Nobel Lecture: The Development of the Space-Time View of Quantum Electrodynamics. Nobel Foundation. December 11, 1965 [July 14, 2016].

- ^ Mehra 1994,第246–248页.