User:SSYoung/Sandbox2

https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=English_language&oldid=827542622

| 英语 | |

|---|---|

| English | |

| 发音 | /ˈɪŋɡlɪʃ/[1] |

| 区域 | 全球各地 |

母语使用人数 | 3.6-4亿 (2006年)[2] 以英语为第二語言的人数:4亿[2] 以英语为外语的人数:6-7亿[2] 使用英语的总人数:14-15亿[2] |

| 語系 | |

| 早期形式 | |

| 文字 | |

| 手势符号英语(多种手语系统) | |

| 官方地位 | |

| 作为官方语言 | |

| 語言代碼 | |

| ISO 639-1 | en |

| ISO 639-2 | eng |

| ISO 639-3 | eng |

| Glottolog | stan1293[4] |

| 语言瞭望站 | 52-ABA |

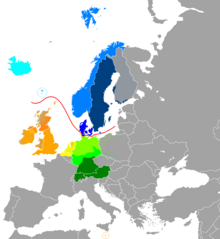

英语圈国家,英语为多数人口的母语

英语是官方语言,但不是多数人口的母语 | |

英语(英語:English)是日耳曼语族西日耳曼語支的一种语言,最早使用于中世纪早期的英格兰,如今已是全球通用语。[5][6] Named after the Angles, one of the Germanic tribes that migrated to England, it ultimately derives its name from the Anglia (Angeln) peninsula in the Baltic Sea. It is closely related to the Frisian languages, but its vocabulary has been significantly influenced by other Germanic languages, particularly Norse (a North Germanic language), as well as by Latin and Romance languages, especially French.[7]

English has developed over the course of more than 1,400 years. The earliest forms of English, a set of Anglo-Frisian dialects brought to Great Britain by Anglo-Saxon settlers in the 5th century, are called Old English. Middle English began in the late 11th century with the Norman conquest of England, and was a period in which the language was influenced by French.[8] Early Modern English began in the late 15th century with the introduction of the printing press to London and the King James Bible, and the start of the Great Vowel Shift.[9]

Through the worldwide influence of the British Empire, modern English spread around the world from the 17th to mid-20th centuries. Through all types of printed and electronic media, and spurred by the emergence of the United States as a global superpower, English has become the leading language of international discourse and the lingua franca in many regions and in professional contexts such as science, navigation and law.[10]

English is the third most widespread native language in the world, after Standard Chinese and Spanish.[11] It is the most widely learned second language and is either the official language or one of the official languages in almost 60 sovereign states. There are more people who have learned it as a second language than there are native speakers. English is the most commonly spoken language in the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, Australia, Ireland and New Zealand, and it is widely spoken in some areas of the Caribbean, Africa and South Asia.[12] It is a co-official language of the United Nations, of the European Union and of many other world and regional international organisations. It is the most widely spoken Germanic language, accounting for at least 70% of speakers of this Indo-European branch. English has a vast vocabulary, and counting exactly how many words it has is impossible.[13][14]

Modern English grammar is the result of a gradual change from a typical Indo-European dependent marking pattern with a rich inflectional morphology and relatively free word order, to a mostly analytic pattern with little inflection, a fairly fixed SVO word order and a complex syntax.[15] Modern English relies more on auxiliary verbs and word order for the expression of complex tenses, aspect and mood, as well as passive constructions, interrogatives and some negation. Despite noticeable variation among the accents and dialects of English used in different countries and regions – in terms of phonetics and phonology, and sometimes also vocabulary, grammar and spelling – English-speakers from around the world are able to communicate with one another with relative ease.

分类[编辑]

英语组包括

英语在语言学系属分类中属于印欧语系日耳曼语族下的西日耳曼语支,[16]古英语源自北海沿岸的日耳曼族群和语言连续体。这一族群语言如今属于西日耳曼语支的盎格鲁-弗里西语组,其中的弗里西语是与现代英语亲缘关系最近的活语言。低地德语(或低地撒克逊语)也与英语有很近的亲缘关系。英语、弗里西语和低地德语有时被一同划分为因格沃内语(又称北海日耳曼语),但这一分类方式存在争议。[17]古英语发展成为中古英语,之后逐渐形成现代英语。[18]古英语的中古英语的部分方言发展成为盎格鲁-弗里西语组当中英语组的其他几种语言,包括低地蘇格蘭語[19]和已经绝迹的两种爱尔兰方言芬戈语和约拉语。[20]

英语的在不列颠群岛的发展与冰岛语、法罗语等语言类似,都独立于欧洲大陆日耳曼语言,受其影响较小。同时,英语本身在演化过程中变化巨大。因此,英语与任何一种欧洲大陆日耳曼语之间都无法相互理解,在词汇、句法和语音上也存在差异。然而欧陆的荷兰语和弗里西语等语言与英语,尤其是早期的英语之间存在较强的关系。[21]

但英语与冰岛语和法罗语发展史不同的是,不列颠群岛在历史上长期受到其他族群语言的入侵,尤其是古诺尔斯语和诺曼法语。这两种语言对英语造成了重要的影响,在英语中留下了深刻的印记,导致英语的词汇和语法与其演化支之外的许多语言有相似之处,但与这些语言不能相互理解。因此有学者提出中古英语克里奥尔语假说,认为英语应当被视为一种混合语或克里奥尔语。尽管学术界广泛承认现代英语的词汇和语法受这些语言影响颇深,但语言接触领域主流意见并不将英语视作真正的混合语言。[22][23]

英语与荷兰语、德语、瑞典语等其他日耳曼语言的起源相同,因此同属日耳曼语族。[24]其演变史表明,这些语言均源自一个共同祖先原始日耳曼語。这些日耳曼语言的共同特征包括情态动词的使用、强弱变化动词的区分,以及原始印歐語辅音的音变。其中原始印欧语辅音音变即为格林定律和維爾納定律。[25]

日耳曼语中的强变化动词是指通过元音变换构造时态的动词,而弱变化动词则是通过添加词缀的方式构造时态。[25]例如强变化动词“唱歌”与弱变化动词“笑”在英语、德语和荷兰语三种日耳曼语言中的时态变化如下:

| 强变化动词(“唱歌”) | 弱变化动词(“笑”) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 不定式 | 过去式 | 过去分词 | 不定式 | 过去式 | 过去分词 | |

| 英语 | sing | sang | sung | laugh | laughed | laughed |

| 德语 | singen | sang | gesungen | lachen | lachte | gelacht |

| 荷兰语 | zingen | zong | gezongen | lachen | lachte | gelachen |

同时根据格林定律,日耳曼语言中表示“脚”的单词以辅音/f/开头,而其他印欧语言中的同源词则以/p/开头,这两个音素均来源自原始印欧语的*p:[25]

| 日耳曼语族 | 印欧语系其他语言 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 英语 | foot | 拉丁语 | pes,词干“ped-” |

| 德语 | Fuß | 现代希腊语 | πόδι(拉丁字母转写:pódi) |

| 荷兰语 | voet | 俄语 | под(拉丁字母转写:pod) |

| 挪威语和瑞典语 | fot | 梵语 | पद्(拉丁字母转写:pád) |

英语与弗里西语同被归类为盎格鲁-弗里西语组是因为二者有更多的相似特征,例如原始日耳曼语中的软腭音在这两种语言中已经顎音化。以这些语言中表示“奶酪”的单词为例:[25]

| 盎格鲁-弗里西语组 | 日耳曼语族其他语言 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 英语 | cheese,“ch”已顎音化 | 德语 | Käse,“k”未顎音化 |

| 弗里西语 | tsiis,“ts”已顎音化 | 荷兰语 | kaas,“k”未顎音化 |

历史[编辑]

原始日耳曼语到古英语[编辑]

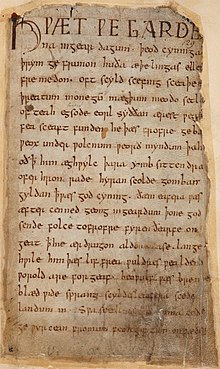

Hƿæt ƿē Gārde / na ingēar dagum þēod cyninga / þrym ge frunon...

现代英语:"Listen! We of the Spear-Danes from days of yore have heard of the glory of the folk-kings..."

中文翻译:“诸位安静!我们已经听说,在遥远的过去,丹麦的王公首领……”[註 1]

英语最早期的形式称为古英语或盎格魯-撒克遜語(约公元550年-1066年)。古英语源自弗里西亞、下萨克森、日德兰半岛和瑞典南部等沿海地区,起源于当地盎格魯人、撒克遜人和朱特人等日耳曼民族使用的北海日耳曼方言。公元5世纪,盎格鲁-撒克逊人迁徙至不列颠群岛,罗马帝国在此地的统治就此结束。在罗马帝国不列颠尼亚行省时期(公元43年-409年),不列颠群岛盛行古布立吞語(属凯尔特语族)和罗马人入侵带来的拉丁语。到公元7世纪时,盎格鲁-撒克逊人使用的日耳曼语已经取而代之,成为不列颠的主流语言。[26][27][28]“英格兰”(England)和“英语”(English)的名称(原作Ænglaland和Ænglisc)就来自盎格鲁人(Angles)这一名称。[29]

古英语主要分为四种方言:麦西亚与诺森布里亚两种盎格鲁方言,以及肯特与西撒克逊两种撒克逊方言。[30]随着威塞克斯王国的强盛以及阿爾弗雷德大帝在9世纪推行的教育改革,西撒克逊方言逐渐成为古英语的标准写法。[31]古英语史诗《貝奧武夫》即是以西撒克逊方言写成,而最早的英语诗歌《卡德蒙的讚美詩》则是以诺森布里亚方言创作。[32]然而现代英语主要是自麦西亚方言发展而来,低地苏格兰语则主要来自诺森布里亚方言。[33]早期古英语有少量文本以卢恩字母书写。[33]至6世纪时已经采用拉丁字母,以半安色尔体书写。其字母表中还包括卢恩字母wynn⟨ƿ⟩和thorn⟨þ⟩,以及拉丁字母变体eth⟨ð⟩和ash⟨æ⟩。[33][34]

古英语与现代英语差异巨大,当代的英语使用者已经难以理解。古英语与古弗里西语亲缘关系最近,其语法与现代德语相似。古英语语法中名词、形容词、代词和动词在词形变化中有更多的词尾和变化形式,语序也比现代英语更自由。现代英语中仅有代词存在变格(如第三人称代词主格“he”,宾格“him,所有格/属格“his”),动词词尾也较少(第一人称“I have”,第三人称单数“he has”);但古英语的名词和代词都会根据不同的格改变词尾,动词根据人称和数的词尾变化也有更多形式。[35][36][37]

以公元1000年翻译的《马太福音》8:20为例,可见古英语中不同格和数的名词和动词词尾变化:

- 古英语:Foxas habbað holu and heofonan fuglas nest ...

- 词尾变化:Fox-as habb-að hol-u and heofon-an fugl-as nest-∅

- 逐词对应现代英语:fox-(主格复数) have-(现在式复数) hole-(宾格复数) and heaven-(属格单数) bird-(主格复数) nest-(宾格复数)

- 现代英语译文:"Foxes have holes and the birds of heaven nests"[38]

- 中文译文:“狐狸有洞,天空的飛鳥有窩”[註 2]

中古英语[编辑]

现代英语:Although, from the beginning, Englishmen had three manners of speaking, southern, northern and midlands speech in the middle of the country, … Nevertheless, through intermingling and mixing, first with Danes and then with Normans, amongst many the country language has arisen, and some use strange stammering, chattering, snarling, and grating gnashing.

中文译文:“尽管从一开始,英国人就有三种说话方式:南方话、北方话和中部地区的米德兰兹话,……然而随着(各语言和民族)混杂,最先是丹麦人,后来是诺曼人,这个国家就出现了各种不同的语言,有奇怪的结结巴巴、喋喋不休、大喊大叫,还有吱吱嘎嘎的咬牙声。”

公元8世纪至12世纪,古英语在語言接觸的影响下逐渐演变为中古英语。中古英语的具体通行时间在学术界没有统一定义,一般认为是自11世纪威廉一世征服英格兰开始,至15世纪印刷术传至英国和16世纪英格兰宗教改革为止,其中《牛津英语词典》第3版采用的定义是1150年至1500年,[40]《大英百科全书》则定义这一时代自1100年左右开始,结束于1500年。[41]

最初在公元8世纪至9世纪,来自斯堪的纳维亚的诺尔斯人入侵不列颠群岛北部,其使用的古诺尔斯语(属北日耳曼语支)与古英语密切融合。诺尔斯语对约克郡附近丹麥區的东北部古英语方言影响最深,当地也是诺尔斯人的统治中心。时至今日,低地苏格兰语和英格兰北部的英语方言中仍然显著保留了古诺尔斯语的特征。然而英格兰中部地区的林赛则是古英语吸收诺尔斯语影响的关键地区。公元920年,林赛从诺尔斯人手中回归到盎格鲁-撒克逊人的统治下,当地方言中吸收的诺尔斯语特征随即扩散至未与诺尔斯人密切接触过的地区,影响了这些地区的英语方言。现代英语各种方言变体中都遗留了诺尔斯语的影响,例如以th-开头的代词(they, them, their)取代了盎格鲁-撒克逊人最初使用的h-开头代词(hie, him, hera)。[42]

1066年诺曼征服英格兰,此前融合了诺尔斯语影响的古英语又开始与古诺曼语接触。古诺曼语属于罗曼语族,是古法语的一种方言,与现代法语关系密切。英格兰的诺曼语随后逐渐发展成为盎格鲁-诺曼语,通行于精英阶层和上层贵族,下层民众则仍然使用盎格鲁-撒克逊语言。因此,诺曼语为英语带来的大量外来词汇多与政治、法律和贵族社会相关。[43]中古英语中大量吸收古法语和拉丁语词汇,其中法语借词在14世纪末至15世纪达到高峰。英语中40%的法语借词在1500年之前已经首次出现,其中很多词语在现代英语词汇中仍然有重要地位,例如现代英语中的peace(意为“和平”)一词明显源自盎格鲁-诺曼语和古法语单词pais。[40]

中古英语极大地简化了古英语中的词形变化,其原因可能是为了调和古诺尔斯语及古诺曼语之间的差异。古诺尔斯语和古诺曼语的构词形态相似,但词形屈折变化明显不同。中古英语中主格和宾格之间的区分基本消失,仅在人称动词中保留二者区别;古英语中的工具格在中古英语中也已经消失;属格仅用于描述所属关系。中古英语的屈折系统调整了许多不规则的词形变化形式,使之更有规则,[44]进而简化了一致系统,减少了语序的灵活性。[45]

1250年至1400年期间,中古英语的文学方言逐步成形,其正字法受到盎格鲁-诺曼语书写系统的影响。[41]但直至14世纪中期的文本仍然在地区之间差异巨大,中古英语尚未成为通用的语言。14世纪末则已经出现大量中古英语文献,文学作品、专业作品和官方文献中都大量使用这种语言,此时的中古英语已经成为文学创作的主要语言,以中古英语写成的宗教、科学和医学文本也逐渐增加。中古英语时期的重要文学作品包括杰弗里·乔叟的《坎特伯雷故事集》、托马斯·马洛礼的《亞瑟之死》等,此时期还出现了最早的《圣经》完整英文译本《威克理夫聖經》。[40][46]

近代英语[编辑]

15世纪末至16世纪,中古英语逐渐演变为近代英语。近代英语通行于1500年至1700年,这段时间与都铎王朝(1485年-1603年)和斯图亚特王朝(1603年-1714年)重合。这期间的英语发音出现重要变化,史称“元音大推移”,其拼写和语法也趋于规范化。[49][50]

元音大推移是一次链变,主要影响的是中古英语中的重读长元音。在这一过程中,每个元音的变化都导致元音系统中的下一元音随之音变。中元音和开元音的舌位抬高,闭元音则分裂为双元音。[47][48]以单词mite(意为“螨虫”)、meet(意为“遇见”)和mate(意为“同伴”)为例:mite中的长音i在元音大推移之前的中古英语中发音为[i:],近代英语中则变为双元音,现发音为[ai];meet中的长音e原本发音为[e:],在元音大推移后变为长音i最初的发音[i:];mate中的长音a原本发音为[a:],后变为前元音,之后又变为长音e原本的发音[e:]。[50]中古英语的拼写很多保留至现代,而元音大推移造成很多词语发音变化,导致其拼写与发音不能按规律对应。元音大推移还使得英语中的元音字母与其他语言的相应字母发音产生极大差异。[47][48]

在亨利五世统治期间,英语开始进入社会上层。大约1430年,西敏地区的衡平法院开始以英文书写官方文件。伦敦和東米德蘭地区的方言发展而成的大法庭标准英语(Chancery Standard)成为英文的标准形式。1476年,威廉·卡克斯頓将印刷术引进英格兰,开始在伦敦印刷书籍,进一步扩大了这种英语的影响力。[51]近代英语时期的主要文学作品包括威廉·莎士比亚的著作以及英王詹姆斯一世下令翻译的《钦定版圣经》。在元音大推移之后,近代英语与现代英语的发音仍有许多不同之处。例如,近代英语中knight、gnat和sword等词语中仍然存在复辅音/kn ɡn sw/,而现代英语中这些词语的复辅音已经消失,仅读作/n n s/。莎士比亚作品中的一些语法特征亦能体现近代英语与现代英语存在的区别。[52]

以近代英语撰写的1611年版英王钦定版圣经为例,其中《马太福音》8:20为:

- The Foxes haue holes and the birds of the ayre haue nests ...[38]

从这句中可以看出近代英语中格和句子结构的变化,以及借词和词义变化。近代英语中已经失去格的变化,以主-谓-宾的语序组成句子结构,用介词of表示非所属关系的属格。这一句中ayre一词源于法语借词;bird一词原意为“筑巢”,在此变化为“鸟”的意思,取代了古英语中原本表示“鸟”的单词fugol。[38]

现代英语及传播[编辑]

18世纪晚期时,随着大英帝国全球殖民和地缘政治优势,英语也广泛传播。英国在商业、科技、外交、艺术和教育等领域都占据优势,使英语成为首个真正的全球通用语言,进而促进了国际间交流。[53][10]英国在世界各地建立殖民地,将英语推行至北美、印度、非洲部分区域、澳大拉西亚和其他多个地区,这些地区又各自形成了自己的读写标准。到后殖民时期,一些独立的新国家国内有多种原住民语言,为某一种语言赋予较高地位会造成原住民语言之间的不平等,导致政治难题,因此继续以英语为官方语言。[54][55][56]20世纪时,美国经济文化影响力日益增强,二战后更成为超级大国,而英国广播公司等媒体向全球播送英语内容,[57]更大大推动了英语在全球的扩张。[58][59]21世纪时,英语已经成为人类历史上所有语言中使用最广泛的一种。[60]

现代英语在早期发展中的一大关键是逐渐确定了标准用法的成文规范,并通过公立教育机构和政府出版物等官方媒体推广。1755年,英国文学家塞缪尔·约翰逊出版了《约翰逊字典》,制定了一系列拼写习惯和用法标准。1828年,诺亚·韦伯斯特出版了《韦氏词典》,为美国英语确定了读写规范,与英国英语的标准相独立。在英国,使用不标准的英语或社会下层方言逐渐被视为羞耻,促使上层阶级使用的英语形式在中产阶级中迅速推广。[61]

在语法方面,现代英语几乎已经完全失去格的变化,仅在代词中还有所保留,例如第三人称代词he、she的宾格him、her,who的宾格whom。现代英语中的主-谓-宾词序也基本固定。[61]以do等助动词引导否定和疑问句也已经成为现代英语的通用用法,而早期的英语仅在疑问句中以do为助动词,且并非必需。[62]以动词have引导否定和疑问句也逐渐成为规范的用法。-ing结尾表示进行时态的用法扩展至新的语言结构,had been being built类似的形式越发常见。很多不规则动词继续缓慢趋向规则化,例如动词dream(意为“做梦”)过去式和过去分词的规则变化形式dreamed逐渐取代dreamt这一不规则形式。以分析性变化代替词语屈折变化的用法也比过去更加常见,例如用more polite代替politer表示polite(意为“有礼貌的”)的比较级形式。随着美国英语在媒体文化中占据强势地位,以及美国强大的世界影响力,英国英语也受到美国英语的影响而发生变化。[63][64][65]

地理分布[编辑]

根据世界经济论坛2016年的数据,全球使用英语的人口总数约为15亿左右,其中4亿人口以英语为母语,其他11亿则是以英语为第二语言或外语。[66]语言学家大衛·克里斯托2006年的估计数据认为英语母语人口总数约为4亿,另有4亿人以英语为第二语言,6亿至7亿人以英语为外语,使用英语的总人口数约为14至15亿。[2]按照民族语的统计数据,英语仅次于汉语和西班牙语,是世界上母语人数第三多的语言。[11]若将母语人口和非母语人口合并计算,英语则可能是全球使用最广泛的语言(具体估算方法不一)。[60][67][68][69]在每个大洲和大洋都有使用英语的社群。[70]英语已经成为全球通用语,也是母语不互通者之间交流时常使用的语言。[5][6][71]

三个语言圈[编辑]

印度语言学家布拉吉·卡齐鲁将使用英语的国家分为三个“语言圈”。[72]在他的模型中,最内层“内圈”(inner circle)以英语为主要语言,大量人口以英语为母语;中间层“外圈”(outer circle)国家有少部分人口以英语为母语,但英语在这些国家广泛用于教育、传媒,地方政府也可能使用英语作为工作语言;最外层“扩展圈”(expanding circle)国家在历史上和政府工作中都不使用英语,但有很多人学习英语作为外语。分类标准考虑了英语在不同国家的传播过程,不同使用者掌握英语的途径,以及各国使用英语的广泛程度。三个圈的国家并非固定,可能会随时间推移而改变。[73]

大量人口以英语为母语的国家,即上述内圈国家包括英国、美国、澳大利亚、加拿大、爱尔兰和新西兰,这些国家中的主流人口以英语为母语。另外还有南非有相当数量的少数族裔使用英语。这些国家按照英语母语人口数量排列依次为美国(2.31亿以上)[74]、英国(6000万)[75][76][77][78]、加拿大(1900万)[79]、澳大利亚(1700万以上)[80]、南非(480万)[81]、爱尔兰(350-380万)[75]和新西兰(370万)[82]。在这些国家中,母语使用者的子女直接从父母学习英语。当地的非英语母语者或新移民也需要学习英语以融入社区和工作。[83]这些内圈国家是英语在全世界的传播的源头。[73]

以英语为第二语言或外语的人数约为4.7亿至10亿,具体估计数字由于对使用流利程度的判断标准不同而存在差别。[12]语言学家大卫·克里斯托在2003年估计英语非母语者人数越是母语者人数的三倍。[67]在卡齐鲁的三圈模型中,外圈国家包括菲律宾[84]、牙买加[85]、印度[86]、巴基斯坦[86]、新加坡[87]和尼日利亚[88][89]等国。这些国家的英语母语者比例较小,但英语在教育、政治、国内商业等领域有重要地位,在学校教学和政府工作中广泛使用。[90]

这些外圈国家有数百万人口以英语的各种方言为母语,从英文克里奥尔语到更加标准的英语变体都有使用。很多使用者是在日常成长生活中逐渐学会英语的,例如广播传媒以及学校教学,尤其是学校的教学语言影响更大。出生在非英语母语家庭者在学习英语的过程中会受到其另一种语言的影响,对语法的影响尤其明显。受影响之后的英语变体中会出现内圈国家罕用的词汇,语法和语音亦可能于内圈国家英语存在差别。内圈国家的标准英语在外圈国家常被视为英语用法的规范。[83]

三圈模型中的扩展圈国家包括波兰、中国、巴西、德国、日本、印度尼西亚、埃及等国家。在这些国家,英语在教育中作为外语课程,其国内有大量以英语为外语的使用者。[91][92]英语作为第一语言、第二语言和外语的界限存在争议,在不同国家的标准亦有不同,且会随时间变化。[90]例如荷兰和其他一些欧洲国家,以英语为第二语言者极为常见,80%以上的人口都能使用英语。[93]因而其国民常以英语与外国人交流,在高等教育中也常用英语。在这些国家中,英语不具有官方地位,也不是政府工作语言,但英语的适用范围之广,使其更接近外圈国家,处于两个圈的交界。在全球语言中,像英语这样,第二语言和外语使用者远多于母语使用者的现象十分罕见。[94]

扩展圈国家中,很多英语使用者会用英语与其他扩展圈国家的人交流,并非为与英语母语者沟通。[95]国际交流中广泛使用各种英语变体, Non-native varieties of English are widely used for international communication, and speakers of one such variety often encounter features of other varieties.[96] Very often today a conversation in English anywhere in the world may include no native speakers of English at all, even while including speakers from several different countries.[97]

Pie chart showing the percentage of native English speakers living in "inner circle" English-speaking countries. Native speakers are now substantially outnumbered worldwide by second-language speakers of English (not counted in this chart).

Pluricentric English[编辑]

English is a pluricentric language, which means that no one national authority sets the standard for use of the language.[98][99][100][101] But English is not a divided language,[102] despite a long-standing joke originally attributed to George Bernard Shaw that the United Kingdom and the United States are "two countries separated by a common language".[103] Spoken English, for example English used in broadcasting, generally follows national pronunciation standards that are also established by custom rather than by regulation. International broadcasters are usually identifiable as coming from one country rather than another through their accents,[104] but newsreader scripts are also composed largely in international standard written English. The norms of standard written English are maintained purely by the consensus of educated English-speakers around the world, without any oversight by any government or international organisation.[105]

American listeners generally readily understand most British broadcasting, and British listeners readily understand most American broadcasting. Most English speakers around the world can understand radio programmes, television programmes, and films from many parts of the English-speaking world.[106] Both standard and nonstandard varieties of English can include both formal or informal styles, distinguished by word choice and syntax and use both technical and non-technical registers.[107]

The settlement history of the English-speaking inner circle countries outside Britain helped level dialect distinctions and produce koineised forms of English in South Africa, Australia, and New Zealand.[108] The majority of immigrants to the United States without British ancestry rapidly adopted English after arrival. Now the majority of the United States population are monolingual English speakers,[109][74] although English has been given official status by only 30 of the 50 state governments of the US.[110][111]

English as a global language[编辑]

English has ceased to be an "English language" in the sense of belonging only to people who are ethnically English.[112][113] Use of English is growing country-by-country internally and for international communication. Most people learn English for practical rather than ideological reasons.[114] Many speakers of English in Africa have become part of an "Afro-Saxon" language community that unites Africans from different countries.[115]

As decolonisation proceeded throughout the British Empire in the 1950s and 1960s, former colonies often did not reject English but rather continued to use it as independent countries setting their own language policies.[55][56][116] For example, the view of the English language among many Indians has gone from associating it with colonialism to associating it with economic progress, and English continues to be an official language of India.[117] English is also widely used in media and literature, and the number of English language books published annually in India is the third largest in the world after the US and UK.[118] However English is rarely spoken as a first language, numbering only around a couple hundred-thousand people, and less than 5% of the population speak fluent English in India.[119][120] David Crystal claimed in 2004 that, combining native and non-native speakers, India now has more people who speak or understand English than any other country in the world,[121] but the number of English speakers in India is very uncertain, with most scholars concluding that the United States still has more speakers of English than India.[122]

Modern English, sometimes described as the first global lingua franca,[58][123] is also regarded as the first world language.[124][125] English is the world's most widely used language in newspaper publishing, book publishing, international telecommunications, scientific publishing, international trade, mass entertainment, and diplomacy.[125] English is, by international treaty, the basis for the required controlled natural languages[126] Seaspeak and Airspeak, used as international languages of seafaring[127] and aviation.[128] English used to have parity with French and German in scientific research, but now it dominates that field.[129] It achieved parity with French as a language of diplomacy at the Treaty of Versailles negotiations in 1919.[130] By the time of the foundation of the United Nations at the end of World War II, English had become pre-eminent [131] and is now the main worldwide language of diplomacy and international relations.[132] It is one of six official languages of the United Nations.[133] Many other worldwide international organisations, including the International Olympic Committee, specify English as a working language or official language of the organisation.

Many regional international organisations such as the European Free Trade Association, Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN),[59] and Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) set English as their organisation's sole working language even though most members are not countries with a majority of native English speakers. While the European Union (EU) allows member states to designate any of the national languages as an official language of the Union, in practice English is the main working language of EU organisations.[134]

Although in most countries English is not an official language, it is currently the language most often taught as a foreign language.[58][59] In the countries of the EU, English is the most widely spoken foreign language in nineteen of the twenty-five member states where it is not an official language (that is, the countries other than the UK, Ireland and Malta). In a 2012 official Eurobarometer poll, 38 percent of the EU respondents outside the countries where English is an official language said they could speak English well enough to have a conversation in that language. The next most commonly mentioned foreign language, French (which is the most widely known foreign language in the UK and Ireland), could be used in conversation by 12 percent of respondents.[135]

A working knowledge of English has become a requirement in a number of occupations and professions such as medicine[136] and computing. English has become so important in scientific publishing that more than 80 percent of all scientific journal articles indexed by Chemical Abstracts in 1998 were written in English, as were 90 percent of all articles in natural science publications by 1996 and 82 percent of articles in humanities publications by 1995.[137]

Specialised subsets of English arise spontaneously in international communities, for example, among international business people, as an auxiliary language. This has led some scholars to develop the study of English as an auxiliary languages. Globish uses a relatively small subset of English vocabulary (about 1500 words with highest use in international business English) in combination with the standard English grammar. Other examples include Simple English.

The increased use of the English language globally has had an effect on other languages, leading to some English words being assimilated into the vocabularies of other languages. This influence of English has led to concerns about language death,[138] and to claims of linguistic imperialism,[139] and has provoked resistance to the spread of English; however the number of speakers continues to increase because many people around the world think that English provides them with opportunities for better employment and improved lives.[140]

Although some scholars mention a possibility of future divergence of English dialects into mutually unintelligible languages, most think a more likely outcome is that English will continue to function as a koineised language in which the standard form unifies speakers from around the world.[141] English is used as the language for wider communication in countries around the world.[142] Thus English has grown in worldwide use much more than any constructed language proposed as an international auxiliary language, including Esperanto.[143][144]

语音[编辑]

英语不同方言之间语音和音系有所不同,但一般不影响不同方言的互相交流。不同方言的音位清单有不同,音位的发音也存在差别。Phonological variation affects the inventory of phonemes (i.e. speech sounds that distinguish meaning), and phonetic variation is differences in pronunciation of the phonemes. [145]以下主要介绍英国的标准发音标准英音和美国的标准发音通用美式英語,发音采用國際音標表示。[146][147][148]

辅音[编辑]

英语中的大部分方言包含24个辅音,下表以加利福尼亚口音的北美英语[149]和标准英音为例{sfn|König|1994|page=534}}

| 唇音 | 齿间音 | 齿龈音 | 齒齦後音 | 硬顎音 | 软腭音 | 聲門音 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 鼻音 | m | n | ŋ | |||||||||||

| 塞音 | p | b | t | d | k | ɡ | ||||||||

| 塞擦音 | tʃ | dʒ | ||||||||||||

| 擦音 | f | v | θ | ð | s | z | ʃ | ʒ | h | |||||

| 近音 | l | ɹ* | j | w | ||||||||||

*通常写作/r/.

表格中成对出现的阻碍音(即塞音、塞擦音和擦音),如/p b/、/tʃ dʒ/和/s z/, the first is fortis (strong) and the second is lenis (weak). Fortis obstruents, such as /p tʃ s/ are pronounced with more muscular tension and breath force than lenis consonants, such as /b dʒ z/, and are always voiceless. Lenis consonants are partly voiced at the beginning and end of utterances, and fully voiced between vowels. Fortis stops such as /p/ have additional articulatory or acoustic features in most dialects: they are aspirated [pʰ] when they occur alone at the beginning of a stressed syllable, often unaspirated in other cases, and often unreleased [p̚ ] or pre-glottalised [ˀp] at the end of a syllable. In a single-syllable word, a vowel before a fortis stop is shortened: thus nip has a noticeably shorter vowel (phonetically, but not phonemically) than nib [nɪˑp̬].[150]

- lenis stops: bin [b̥ɪˑn], about [əˈbaʊt], nib [nɪˑb̥]

- fortis stops: pin [ˈpʰɪn], spin [spɪn], happy [ˈhæpi], nip [ˈnɪp̚ ] or [ˈnɪˀp]

表中成对出现的八对阻礙音(即塞音、塞擦音和擦音,如/p b/、/tʃ dʒ/和/s z/),每个单元格中左侧音位为强辅音,右侧音位为弱辅音。/p tʃ s/等强阻碍音发音时口腔肌肉更紧张,气流更强,且均为清音;/b dʒ z/等弱阻碍音在语句首尾时是“半浊音”,在元音之间时则为浊音。强塞音/p/在大部分方言中还有额外的发音特征:这个音位在重读音节开头单独出现时为送氣音[pʰ],其他情形多为不送气音,位于音节末尾时常为无声除阻音[p̚ ]或先喉塞音[ˀp]。在单音节单词中,强塞音之前的元音常常会变短,例如bit(意为“一点点”)的元音与bid(意为“竞拍”)相比,在发音上明显更短。[150]

- 弱塞音:bin [b̥ɪˑn](意为“垃圾箱”)、about [əˈbaʊt](意为“关于”)、nib [nɪˑb̥](意为“笔尖”)

- 强塞音:pin [ˈpʰɪn](意为“大头针”)、spin [spɪn](意为“旋转”)、happy [ˈhæpi](意为“快乐的”)、nip [ˈnɪp̚ ]或[ˈnɪˀp](意为“掐”)

标准英音中,边近音/l/存在两个同位異音:一个是“清晰的[l]”,如light(意为“光”)一词开头的辅音;另一个是即“含糊的[ɫ]”即齿龈边近音[ɫ],如full(意为“满的”)一词末尾的辅音。[151]通用美音则在大多数情形下都使用含糊的[ɫ]。[152]

所有的響音(包括流音/l, r/和鼻音/m, n, ŋ/)接在清阻碍音后会出现清化现象,如clay [ˈkl̥ɛɪ̯](意为“陶土”)、snow [ˈsn̥oʊ](意为“雪”)。响音若接在在辅音后且位于词尾则独立构成音节,如paddle [pad.l̩](意为“船桨”)、button [bʌt.n̩](意为“按钮”)。[153]

元音[编辑]

The pronunciation of vowels varies a great deal between dialects and is one of the most detectable aspects of a speaker's accent. The table below lists the vowel phonemes in Received Pronunciation (RP) and General American (GA), with examples of words in which they occur from lexical sets compiled by linguists. The vowels are represented with symbols from the International Phonetic Alphabet; those given for RP are standard in British dictionaries and other publications.

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In RP, vowel length is phonemic; long vowels are marked with a triangular colon ⟨ː⟩ in the table above, such as the vowel of need [niːd] as opposed to bid [bɪd]. GA does not have long vowels.

In both RP and GA, vowels are phonetically shortened before fortis consonants in the same syllable, like /t tʃ f/, but not before lenis consonants like /d dʒ v/ or in open syllables: thus, the vowels of rich [rɪ̆tʃ], neat [niˑt], and safe [sĕɪ̆f] are noticeably shorter than the vowels of ridge [rɪdʒ], need [niːd], and save [seɪv], and the vowel of light [lăɪ̆t] is shorter than that of lie [laɪ]. Because lenis consonants are frequently voiceless at the end of a syllable, vowel length is an important cue as to whether the following consonant is lenis or fortis.[154]

The vowels /ɨ ə/ only occur in unstressed syllables and are a result of vowel reduction. Some dialects do not distinguish them, so that roses and comma end in the same vowel, a dialect feature called weak-vowel merger. GA has an unstressed r-coloured schwa /ɚ/, as in butter [ˈbʌtɚ], which in RP has the same vowel as the word-final vowel in comma.

Phonotactics[编辑]

An English syllable includes a syllable nucleus consisting of a vowel sound. Syllable onset and coda (start and end) are optional. A syllable can start with up to three consonant sounds, as in sprint /sprɪnt/, and end with up to four, as in texts /teksts/. This gives an English syllable the following structure, (CCC)V(CCCC) where C represents a consonant and V a vowel; the word strengths /strɛŋkθs/ is thus an example of the most complex syllable possible in English. The consonants that may appear together in onsets or codas are restricted, as is the order in which they may appear. Onsets can only have four types of consonant clusters: a stop and approximant, as in play; a voiceless fricative and approximant, as in fly or sly; s and a voiceless stop, as in stay; and s, a voiceless stop, and an approximant, as in string.[155] Clusters of nasal and stop are only allowed in codas. Clusters of obstruents always agree in voicing, and clusters of sibilants and of plosives with the same point of articulation are prohibited. Furthermore, several consonants have limited distributions: /h/ can only occur in syllable initial position, and /ŋ/ only in syllable final position.[156]

Stress, rhythm and intonation[编辑]

Stress plays an important role in English. Certain syllables are stressed, while others are unstressed. Stress is a combination of duration, intensity, vowel quality, and sometimes changes in pitch. Stressed syllables are pronounced longer and louder than unstressed syllables, and vowels in unstressed syllables are frequently reduced while vowels in stressed syllables are not.[157] Some words, primarily short function words but also some modal verbs such as can, have weak and strong forms depending on whether they occur in stressed or non-stressed position within a sentence.

Stress in English is phonemic, and some pairs of words are distinguished by stress. For instance, the word contract is stressed on the first syllable (/ˈkɒntrækt/ KON-trakt) when used as a noun, but on the last syllable (/kənˈtrækt/ kən-TRAKT) for most meanings (for example, "reduce in size") when used as a verb.[158][159][160] Here stress is connected to vowel reduction: in the noun "contract" the first syllable is stressed and has the unreduced vowel /ɒ/, but in the verb "contract" the first syllable is unstressed and its vowel is reduced to /ə/. Stress is also used to distinguish between words and phrases, so that a compound word receives a single stress unit, but the corresponding phrase has two: e.g. to búrn óut versus a búrnout, and a hótdog versus a hót dóg.[161]

In terms of rhythm, English is generally described as a stress-timed language, meaning that the amount of time between stressed syllables tends to be equal. Stressed syllables are pronounced longer, but unstressed syllables (syllables between stresses) are shortened. Vowels in unstressed syllables are shortened as well, and vowel shortening causes changes in vowel quality: vowel reduction.

Regional variation[编辑]

| Varieties of Standard English and their features[162] | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phonological features |

United States |

Canada | Republic of Ireland |

Northern Ireland |

Scotland | England | Wales | South Africa |

Australia | New Zealand |

| father–bother merger | yes | yes | ||||||||

| /ɒ/ is unrounded | yes | yes | yes | |||||||

| /ɜːr/ is pronounced [ɚ] | yes | yes | yes | yes | ||||||

| cot–caught merger | possibly | yes | possibly | yes | yes | |||||

| fool–full merger | yes | yes | ||||||||

| /t, d/ flapping (latter-ladder merger) | yes | yes | possibly | often | rarely | rarely | rarely | rarely | yes | often |

| trap–bath split | possibly | possibly | yes | yes | yes | often | yes | |||

| non-rhotic (/r/-dropping after vowels) | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | |||||

| close vowels for /æ, ɛ/ | yes | yes | yes | |||||||

| /l/ can always be pronounced [ɫ] | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | ||||

| /ɑːr/ is fronted | possibly | yes | yes | |||||||

| word | RP | GA | Can | sound change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| THOUGHT | /ɔ/ | /ɔ/ or /ɑ/ | /ɑ/ | cot–caught merger |

| CLOTH | /ɒ/ | lot–cloth split | ||

| LOT | /ɑ/ | father–bother merger | ||

| PALM | /ɑː/ | |||

| PLANT | /æ/ | /æ/ | trap–bath split | |

| BATH | ||||

| TRAP | /æ/ |

Varieties of English vary the most in pronunciation of vowels. The best known national varieties used as standards for education in non English-speaking countries are British (BrE) and American (AmE). Countries such as Canada, Australia, Ireland, New Zealand and South Africa have their own standard varieties which are less often used as standards for education internationally. Some differences between the various dialects are shown in the table "Varieties of Standard English and their features".[162]

English has undergone many historical sound changes, some of them affecting all varieties, and others affecting only a few. Most standard varieties are affected by the Great Vowel Shift, which changed the pronunciation of long vowels, but a few dialects have slightly different results. In North America, a number of chain shifts such as the Northern Cities Vowel Shift and Canadian Shift have produced very different vowel landscapes in some regional accents.

Some dialects have fewer or more consonant phonemes and phones than the standard varieties. Some conservative varieties like Scottish English have a voiceless [ʍ] sound in whine that contrasts with the voiced [w] in wine, but most other dialects pronounce both words with voiced [w], a dialect feature called wine–whine merger. The unvoiced velar fricative sound /x/ is found in Scottish English, which distinguishes loch /lɔx/ from lock /lɔk/. Accents like Cockney with "h-dropping" lack the glottal fricative /h/, and dialects with th-stopping and th-fronting like African American Vernacular and Estuary English do not have the dental fricatives /θ, ð/, but replace them with dental or alveolar stops /t, d/ or labiodental fricatives /f, v/.[163][164] Other changes affecting the phonology of local varieties are processes such as yod-dropping, yod-coalescence, and reduction of consonant clusters.

General American and Received Pronunciation vary in their pronunciation of historical /r/ after a vowel at the end of a syllable (in the syllable coda). GA is a rhotic dialect, meaning that it pronounces /r/ at the end of a syllable, but RP is non-rhotic, meaning that it loses /r/ in that position. English dialects are classified as rhotic or non-rhotic depending on whether they elide /r/ like RP or keep it like GA.[165]

There is complex dialectal variation in words with the open front and open back vowels /æ ɑː ɒ ɔː/. These four vowels are only distinguished in RP, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa. In GA, these vowels merge to three /æ ɑ ɔ/,[166] and in Canadian English they merge to two /æ ɑ/.[167] In addition, the words that have each vowel vary by dialect. The table "Dialects and open vowels" shows this variation with lexical sets in which these sounds occur.

语法[编辑]

英语是典型的印欧语系语言,采用主宾格配列。但与其他印欧语言不同,英语舍弃了屈折变格系统,更趋向分析语的结构,仅人称代词保留了比其他词类更强的变格形式。英语中分为至少七种词性:动词、名词、形容词、副词、限定词(含冠词)、介词和连词。另有一些句法分析中把代词与名词相区分,单独作为一种词性,或将连词分为从属连词和并列连词,或加入感叹词作为独立的词性。[168]英语中亦有丰富的助动词,例如have和do,以表达时态、语气和语态等。[169]疑问句就以do等助动词、疑問詞移位和某些动词词序倒置等为标记。

Unlike other Indo-European languages though, English has largely abandoned the inflectional case system in favor of analytic constructions. Only the personal pronouns retain morphological case more strongly than any other word class. English distinguishes at least seven major word classes: verbs, nouns, adjectives, adverbs, determiners (including articles), prepositions, and conjunctions. Some analyses add pronouns as a class separate from nouns, and subdivide conjunctions into subordinators and coordinators, and add the class of interjections.[168] English also has a rich set of auxiliary verbs, such as have and do, expressing the categories of mood and aspect. Questions are marked by do-support, wh-movement (fronting of question words beginning with wh-) and word order inversion with some verbs.

以下句子中包含了七种词类的示例,句子意为“委员会主席与这个喋喋不休的政客在会谈一开始就爆发了激烈的冲突”。[170]

| The | chairman | of | the | committee | and | the | loquacious | politician | clashed | violently | when | the | meeting | started |

| 限定词 | 名词 | 介词 | 限定词 | 名词 | 连词 | 限定词 | 形容词 | 名词 | 动词 | 副词 | 连词 | 限定词 | 名词 | 动词 |

日耳曼语言中的一些语法共性在英语中也有保留,例如强弱变化动词变化的区别。但日耳曼语言中常见性和格的变化,英语中则仅在代词系统和中保留这两种现象。 Some traits typical of Germanic languages persist in English, such as the distinction between irregularly inflected strong stems inflected through ablaut (i.e. changing the vowel of the stem, as in the pairs speak/spoke and foot/feet) and weak stems inflected through affixation (such as love/loved, hand/hands). Vestiges of the case and gender system are found in the pronoun system (he/him, who/whom) and in the inflection of the copula verb to be.

名词和名词短语[编辑]

英语中的名词仅受数和所属关系的影响。新名词可以通过派生和合成的方法创造。根据语义的不同,名词可以分为专有名词和普通名词,其中普通名词又分为具体名词和抽象名词;根据语法功能的不同,名词还可以分为可数名词和不可数名词两类。[171]

大多数可数名词可以在末尾加上后缀-s表示复数,少数可数名词的复数形式变化不规则,例如:[172][171]

规则可数名词的变化:

- 单数:cat(猫)、dog(狗)

- 复数:cats、dogs

不规则可数名词的变化:

- 单数:man(男人)、woman(女人)、foot(脚)、fish(鱼)、ox(牛)、mouse(老鼠)

- 复数:men、women、feet、fish、oxen、mice

不可数名词只能通过量词来表示复数,例如:one loaf of bread(一条面包)/ two loaves of bread(两条面包)。[172][171]

所属关系可以通过在名词后添加附着词素-s(即属格后缀)来表示,也可使用介词of。历史上一般对有生命的对象使用-s后缀表示属格,对无生命者使用of,但现在这一区别已不明显,许多英语使用者也使用-s后缀表示无生命名词的属格。标准正字法中,在名词和属格后缀之间以撇号⟨'⟩分隔。[173]两种表示方式如下:[171]

- -s后缀:Kim's father(金的父亲)

- 介词of:The father of Kim

名词可以组成名词短语,即名词在短语中担任中心词,短语中其他的限定词、数量词、连词或形容词则用于修饰名词中心语。Nouns can form noun phrases (NPs) where they are the syntactic head of the words that depend on them such as determiners, quantifiers, conjunctions or adjectives.[174]名词短语可长可短,短者如the man(意为“(特指一个)男人”),仅包含一个限定词the和一个名词man;短语中亦可包含形容词等作为修饰语 Noun phrases can be short, such as the man, composed only of a determiner and a noun. They can also include modifiers such as adjectives (e.g. red, tall, all) ,或限定词等作为指示语and specifiers such as determiners (e.g. the, that). 。名词短语还可以使用and等连词或with等介词,将多个名词结合成一个长短语,例如以下短语中就包含了连词、介词、指示语和修饰语。

the tall man with the long red trousers and his skinny wife with the spectacles(意为:那个身穿红色长裤的高个子男人和他那戴着眼镜的苗条妻子)

名词短语无论长短,在句子中均为一个句法单元。例如在不引起歧义的情况下,表示所属关系的附着词素可以跟在整个名词短语之后,如The President of India's wife(意为“印度总统的妻子”),附着词素可以加在India(意为“印度”)之后,而不必加在President(意为“总统”),仍然表示所属于The President of India(意为“印度总统”)而非India。

But they can also tie together several nouns into a single long NP, using conjunctions such as and, or prepositions such as with, e.g. the tall man with the long red trousers and his skinny wife with the spectacles (this NP uses conjunctions, prepositions, specifiers and modifiers). Regardless of length, an NP functions as a syntactic unit. For example, the possessive enclitic can, in cases which do not lead to ambiguity, follow the entire noun phrase, as in The President of India's wife, where the enclitic follows India and not President.

The class of determiners is used to specify the noun they precede in terms of definiteness, where the marks a definite noun and a or an an indefinite one. A definite noun is assumed by the speaker to be already known by the interlocutor, whereas an indefinite noun is not specified as being previously known. Quantifiers, which include one, many, some and all, are used to specify the noun in terms of quantity or number. The noun must agree with the number of the determiner, e.g. one man (sg.) but all men (pl.). Determiners are the first constituents in a noun phrase.[175]

Adjectives[编辑]

Adjectives modify a noun by providing additional information about their referents. In English, adjectives come before the nouns they modify and after determiners.[176] In Modern English, adjectives are not inflected, and they do not agree in form with the noun they modify, as adjectives in most other Indo-European languages do. For example, in the phrases the slender boy, and many slender girls, the adjective slender does not change form to agree with either the number or gender of the noun.

Some adjectives are inflected for degree of comparison, with the positive degree unmarked, the suffix -er marking the comparative, and -est marking the superlative: a small boy, the boy is smaller than the girl, that boy is the smallest. Some adjectives have irregular comparative and superlative forms, such as good, better, and best. Other adjectives have comparatives formed by periphrastic constructions, with the adverb more marking the comparative, and most marking the superlative: happier or more happy, the happiest or most happy.[177] There is some variation among speakers regarding which adjectives use inflected or periphrastic comparison, and some studies have shown a tendency for the periphrastic forms to become more common at the expense of the inflected form.[178]

代词、格和人称[编辑]

英语代词中保留了许多格和性的屈折变化特性。大部分人称代词的主格和宾格保持了不同,如

第一人称单数主格I和宾格me、

English pronouns conserve many traits of case and gender inflection. The personal pronouns retain a difference between subjective and objective case in most persons (I/me, he/him, she/her, we/us, they/them)

在第三人称单数代词中还保留了性别和有生性/无生性的差别,其中有生的阳性代词为he,有生的阴性代词为{{lang|en|she}],无生的代词为it。as well as a gender and animateness distinction in the third person singular (distinguishing he/she/it).

现代英语中的主格(subjective case)与古英语中的主格(nominative case)相对应,现代英语中的间接格则同时用于表示古英语中存在的宾格(用于受事或及物动词的直接宾语)和与格(用于接受者或及物动词的间接宾语)。[179][180] Subjective case is used when the pronoun is the subject of a finite clause, and otherwise the objective case is used.[181] While grammarians such as Henry Sweet[182] and Otto Jespersen[183] noted that the English cases did not correspond to the traditional Latin based system, some contemporary grammars, for example Huddleston & Pullum (2002), retain traditional labels for the cases, calling them nominative and accusative cases respectively.

Possessive pronouns exist in dependent and independent forms; the dependent form functions as a determiner specifying a noun (as in my chair), while the independent form can stand alone as if it were a noun (e.g. the chair is mine).[184] The English system of grammatical person no longer has a distinction between formal and informal pronouns of address (the old 2nd person singular familiar pronoun thou acquired a pejorative or inferior tinge of meaning and was abandoned), and the forms for 2nd person plural and singular are identical except in the reflexive form. Some dialects have introduced innovative 2nd person plural pronouns such as y'all found in Southern American English and African American (Vernacular) English or youse and ye found in Irish English.

| 人称 | 主格 | 宾格 | 形容词性物主代词 | 名词性物主代词 | 反身代词 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 第一人称单数 | I | me | my | mine | myself |

| 第二人称单数 | you | you | your | yours | yourself |

| 第三人称单数 | he/she/it | him/her/it | his/her/its | his/hers/its | himself/herself/itself |

| 第一人称复数 | we | us | our | ours | ourselves |

| 第二人称复数 | you | you | your | yours | yourselves |

| 第三人称复数 | they | them | their | theirs | themselves |

Pronouns are used to refer to entities deictically or anaphorically. A deictic pronoun points to some person or object by identifying it relative to the speech situation — for example the pronoun I identifies the speaker, and the pronoun you, the addressee. Anaphorical pronouns such as that refer back to an entity already mentioned or assumed by the speaker to be known by the audience, for example in the sentence I already told you that. The reflexive pronouns are used when the oblique argument is identical to the subject of a phrase (e.g. "he sent it to himself" or "she braced herself for impact").[185]

Prepositions[编辑]

Prepositional phrases (PP) are phrases composed of a preposition and one or more nouns, e.g. with the dog, for my friend, to school, in England. Prepositions have a wide range of uses in English. They are used to describe movement, place, and other relations between different entities, but they also have many syntactic uses such as introducing complement clauses and oblique arguments of verbs. For example, in the phrase I gave it to him, the preposition to marks the recipient, or Indirect Object of the verb to give. Traditionally words were only considered prepositions if they governed the case of the noun they preceded, for example causing the pronouns to use the objective rather than subjective form, "with her", "to me", "for us". But some contemporary grammars such as that of Huddleston & Pullum (2002:598–600頁) no longer consider government of case to be the defining feature of the class of prepositions, rather defining prepositions as words that can function as the heads of prepositional phrases.

Verbs and verb phrases[编辑]

English verbs are inflected for tense and aspect, and marked for agreement with third person singular subject. Only the copula verb to be is still inflected for agreement with the plural and first and second person subjects.[177] Auxiliary verbs such as have and be are paired with verbs in the infinitive, past, or progressive forms. They form complex tenses, aspects, and moods. Auxiliary verbs differ from other verbs in that they can be followed by the negation, and in that they can occur as the first constituent in a question sentence.[186][187]

Most verbs have six inflectional forms. The primary forms are a plain present, a third person singular present, and a preterite (past) form. The secondary forms are a plain form used for the infinitive, a gerund–participle and a past participle.[188] The copula verb to be is the only verb to retain some of its original conjugation, and takes different inflectional forms depending on the subject. The first person present tense form is am, the third person singular form is and the form are is used second person singular and all three plurals. The only verb past participle is been and its gerund-participle is being.

| Inflection | Strong | Regular |

|---|---|---|

| Plain present | take | love |

| 3rd person sg. present |

takes | loves |

| Preterite | took | loved |

| Plain (infinitive) | take | love |

| Gerund–participle | taking | loving |

| Past participle | taken | loved |

时态、体貌和语气[编辑]

英语有两种主要时态,过去时和非过去时。过去时态有屈折变化,使用动词的过去式表示。对于规则动词,一般需要添加后缀-ed变为过去式;对于不规则的强变化动词,可能需要添加后缀-t或改变动词词干中的元音。非过去时态动词则一般没有明显标志,仅在第三人称单数时添加后缀-s。[186]以下为动词run(意为“跑”)的三种人称和时态变化。

| 现在时 | 过去时 | |

|---|---|---|

| 第一人称 | I run | I ran |

| 第二人称 | You run | You ran |

| 第三人称 | John runs | John ran |

英语中不存在形态化的将来时态,[189]而是通过助动词will或shall以迂说法表示动作发生在将来。[190]很多英语变体亦使用动词短语be going to构造将来时态,表示不远的将来发生的动作。[191]以下为动词run在三种人称下的将来时态表示方法:

| 将来时 | |

|---|---|

| 第一人称 | I will run |

| 第二人称 | You will run |

| 第三人称 | John will run |

其他体貌的区别则通过助动词编码,主要是have和be,二者区分完成体和非完成体的对立。

have用于表示过去时态的完成体(如'I have run ),be

Further aspectual distinctions are encoded by the use of auxiliary verbs, primarily have and be, which encode the contrast between a perfect and non-perfect past tense (I have run vs. I was running),

并构成过去完成时(and compound tenses such as preterite perfect (I had been running) 和现在完成时。 (I have been running).等时态[192]

英语使用一系列情态助动词来表示语气,如can, may, will, shall 及相应的过去式could, might, would, should。For the expression of mood, English uses a number of modal auxiliaries, such as can, may, will, shall and the past tense forms could, might, would, should.

英语中还存在虚拟语气和祈使语气。There is also a subjunctive and an imperative mood, both based on the plain form of the verb (i.e. without the third person singular -s), and which is used in subordinate clauses (e.g. subjunctive: It is important that he run every day; imperative Run!).[190]

An infinitive form, that uses the plain form of the verb and the preposition to, is used for verbal clauses that are syntactically subordinate to a finite verbal clause. Finite verbal clauses are those that are formed around a verb in the present or preterit form. In clauses with auxiliary verbs they are the finite verbs and the main verb is treated as a subordinate clause. For example, he has to go where only the auxiliary verb have is inflected for time and the main verb to go is in the infinitive, or in a complement clause such as I saw him leave, where the main verb is to see which is in a preterite form, and leave is in the infinitive.

Phrasal verbs[编辑]

English also makes frequent use of constructions traditionally called phrasal verbs, verb phrases that are made up of a verb root and a preposition or particle which follows the verb. The phrase then functions as a single predicate. In terms of intonation the preposition is fused to the verb, but in writing it is written as a separate word. Examples of phrasal verbs are to get up, to ask out, to back up, to give up, to get together, to hang out, to put up with, etc. The phrasal verb frequently has a highly idiomatic meaning that is more specialised and restricted than what can be simply extrapolated from the combination of verb and preposition complement (e.g. lay off meaning terminate someone's employment).[193] In spite of the idiomatic meaning, some grammarians, including Huddleston & Pullum (2002:274頁), do not consider this type of construction to form a syntactic constituent and hence refrain from using the term "phrasal verb". Instead they consider the construction simply to be a verb with a prepositional phrase as its syntactic complement, i.e. he woke up in the morning and he ran up in the mountains are syntactically equivalent.

Adverbs[编辑]

The function of adverbs is to modify the action or event described by the verb by providing additional information about the manner in which it occurs. Many adverbs are derived from adjectives with the suffix -ly, but not all, and many speakers tend to omit the suffix in the most commonly used adverbs. For example, in the phrase the woman walked quickly the adverb quickly derived from the adjective quick describes the woman's way of walking. Some commonly used adjectives have irregular adverbial forms, such as good which has the adverbial form well.

Syntax[编辑]

Modern English syntax language is moderately analytic.[194] It has developed features such as modal verbs and word order as resources for conveying meaning. Auxiliary verbs mark constructions such as questions, negative polarity, the passive voice and progressive aspect.

Basic constituent order[编辑]

English word order has moved from the Germanic verb-second (V2) word order to being almost exclusively subject–verb–object (SVO).[195] The combination of SVO order and use of auxiliary verbs often creates clusters of two or more verbs at the centre of the sentence, such as he had hoped to try to open it.

In most sentences English only marks grammatical relations through word order.[196] The subject constituent precedes the verb and the object constituent follows it. The example below demonstrates how the grammatical roles of each constituent is marked only by the position relative to the verb:

| The dog | bites | the man |

| S | V | O |

| The man | bites | the dog |

| S | V | O |

An exception is found in sentences where one of the constituents is a pronoun, in which case it is doubly marked, both by word order and by case inflection, where the subject pronoun precedes the verb and takes the subjective case form, and the object pronoun follows the verb and takes the objective case form. The example below demonstrates this double marking in a sentence where both object and subject is represented with a third person singular masculine pronoun:

| He | hit | him |

| S | V | O |

Indirect objects (IO) of ditransitive verbs can be placed either as the first object in a double object construction (S V IO O), such as I gave Jane the book or in a prepositional phrase, such as I gave the book to Jane [197]

Clause syntax[编辑]

In English a sentence may be composed of one or more clauses, that may in turn be composed of one or more phrases (e.g. Noun Phrases, Verb Phrases, and Prepositional Phrases). A clause is built around a verb, and includes its constituents, such as any NPs and PPs. Within a sentence one clause is always the main clause (or matrix clause) whereas other clauses are subordinate to it. Subordinate clauses may function as arguments of the verb in the main clause. For example, in the phrase I think (that) you are lying, the main clause is headed by the verb think, the subject is I, but the object of the phrase is the subordinate clause (that) you are lying. The subordinating conjunction that shows that the clause that follows is a subordinate clause, but it is often omitted.[198] Relative clauses are clauses that function as a modifier or specifier to some constituent in the main clause: For example, in the sentence I saw the letter that you received today, the relative clause that you received today specifies the meaning of the word letter, the object of the main clause. Relative clauses can be introduced by the pronouns who, whose, whom and which as well as by that (which can also be omitted.)[199] In contrast to many other Germanic languages there is no major differences between word order in main and subordinate clauses.[200]

Auxiliary verb constructions[编辑]

English syntax relies on auxiliary verbs for many functions including the expression of tense, aspect and mood. Auxiliary verbs form main clauses, and the main verbs function as heads of a subordinate clause of the auxiliary verb. For example, in the sentence the dog did not find its bone, the clause find its bone is the complement of the negated verb did not. Subject–auxiliary inversion is used in many constructions, including focus, negation, and interrogative constructions.

The verb do can be used as an auxiliary even in simple declarative sentences, where it usually serves to add emphasis, as in "I did shut the fridge." However, in the negated and inverted clauses referred to above, it is used because the rules of English syntax permit these constructions only when an auxiliary is present. Modern English does not allow the addition of the negating adverb not to an ordinary finite lexical verb, as in *I know not—it can only be added to an auxiliary (or copular) verb, hence if there is no other auxiliary present when negation is required, the auxiliary do is used, to produce a form like I do not (don't) know. The same applies in clauses requiring inversion, including most questions—inversion must involve the subject and an auxiliary verb, so it is not possible to say *Know you him?; grammatical rules require Do you know him?[201]

Negation is done with the adverb not, which precedes the main verb and follows an auxiliary verb. A contracted form of not -n't can be used as an enclitic attaching to auxiliary verbs and to the copula verb to be. Just as with questions, many negative constructions require the negation to occur with do-support, thus in Modern English I don't know him is the correct answer to the question Do you know him?, but not *I know him not, although this construction may be found in older English.[202]

Passive constructions also use auxiliary verbs. A passive construction rephrases an active construction in such a way that the object of the active phrase becomes the subject of the passive phrase, and the subject of the active phrase is either omitted or demoted to a role as an oblique argument introduced in a prepositional phrase. They are formed by using the past participle either with the auxiliary verb to be or to get, although not all varieties of English allow the use of passives with get. For example, putting the sentence she sees him into the passive becomes he is seen (by her), or he gets seen (by her).[203]

Questions[编辑]

Both yes–no questions and wh-questions in English are mostly formed using subject–auxiliary inversion (Am I going tomorrow?, Where can we eat?), which may require do-support (Do you like her?, Where did he go?). In most cases, interrogative words (wh-words; e.g. what, who, where, when, why, how) appear in a fronted position. For example, in the question What did you see?, the word what appears as the first constituent despite being the grammatical object of the sentence. (When the wh-word is the subject or forms part of the subject, no inversion occurs: Who saw the cat?.) Prepositional phrases can also be fronted when they are the question's theme, e.g. To whose house did you go last night?. The personal interrogative pronoun who is the only interrogative pronoun to still show inflection for case, with the variant whom serving as the objective case form, although this form may be going out of use in many contexts.[204]

Discourse level syntax[编辑]

While English is a subject-prominent language, at the discourse level it tends to use a topic-comment structure, where the known information (topic) precedes the new information (comment). Because of the strict SVO syntax, the topic of a sentence generally has to be the grammatical subject of the sentence. In cases where the topic is not the grammatical subject of the sentence, frequently the topic is promoted to subject position through syntactic means. One way of doing this is through a passive construction, the girl was stung by the bee. Another way is through a cleft sentence where the main clause is demoted to be a complement clause of a copula sentence with a dummy subject such as it or there, e.g. it was the girl that the bee stung, there was a girl who was stung by a bee.[205] Dummy subjects are also used in constructions where there is no grammatical subject such as with impersonal verbs (e.g., it is raining) or in existential clauses (there are many cars on the street). Through the use of these complex sentence constructions with informationally vacuous subjects, English is able to maintain both a topic-comment sentence structure and a SVO syntax.

Focus constructions emphasise a particular piece of new or salient information within a sentence, generally through allocating the main sentence level stress on the focal constituent. For example, the girl was stung by a bee (emphasising it was a bee and not for example a wasp that stung her), or The girl was stung by a bee (contrasting with another possibility, for example that it was the boy).[206] Topic and focus can also be established through syntactic dislocation, either preposing or postposing the item to be focused on relative to the main clause. For example, That girl over there, she was stung by a bee, emphasises the girl by preposition, but a similar effect could be achieved by postposition, she was stung by a bee, that girl over there, where reference to the girl is established as an "afterthought".[207]

Cohesion between sentences is achieved through the use of deictic pronouns as anaphora (e.g. that is exactly what I mean where that refers to some fact known to both interlocutors, or then used to locate the time of a narrated event relative to the time of a previously narrated event).[208] Discourse markers such as oh, so or well, also signal the progression of ideas between sentences and help to create cohesion. Discourse markers are often the first constituents in sentences. Discourse markers are also used for stance taking in which speakers position themselves in a specific attitude towards what is being said, for example, no way is that true! (the idiomatic marker no way! expressing disbelief), or boy! I'm hungry (the marker boy expressing emphasis). While discourse markers are particularly characteristic of informal and spoken registers of English, they are also used in written and formal registers.[209]

Vocabulary[编辑]

English is an immensely rich language in terms of vocabulary, containing more synonyms than any other language.[13] There are words which appear on the surface to mean exactly the same thing but which, in fact, have a slightly different shade of meaning and must be used appropriately if a speaker wants to convey precisely the message they intend to convey.[139] It is generally stated that English has around 170,000 words, or 220,000 if obsolete words are counted; this estimate is based on the last full edition of the Oxford English Dictionary from 1989.[210] Over half of these words are nouns, a quarter adjectives and a seventh verbs. There is one count that puts the English vocabulary at about 1 million words – but that count presumably includes words such as Latin species names, scientific terminology, prefixed and suffixed words, jargon, foreign words of extremely limited English use and technical acronyms.[14]

Due to its status as an international language, English is expeditious when it comes to adopting foreign words, and borrows vocabulary from a large number of other sources. Early studies of English vocabulary by lexicographers, the scholars who formally study vocabulary, compile dictionaries, or both, were impeded by a lack of comprehensive data on actual vocabulary in use from good-quality linguistic corpora,[211] collections of actual written texts and spoken passages. Many statements published before the end of the 20th century about the growth of English vocabulary over time, the dates of first use of various words in English, and the sources of English vocabulary will have to be corrected as new computerised analysis of linguistic corpus data becomes available.[14][212]

Word formation processes[编辑]

English forms new words from existing words or roots in its vocabulary through a variety of processes. One of the most productive processes in English is conversion,[213] using a word with a different grammatical role, for example using a noun as a verb or a verb as a noun. Another productive word-formation process is nominal compounding,[14][212] producing compound words such as babysitter or ice cream or homesick.[213] A process more common in Old English than in Modern English, but still productive in Modern English, is the use of derivational suffixes (-hood, -ness, -ing, -ility) to derive new words from existing words (especially those of Germanic origin) or stems (especially for words of Latin or Greek origin).

Formation of new words, called neologisms, based on Greek or Latin roots (for example television or optometry) is a highly productive process in English and in most modern European languages, so much so that it is often difficult to determine in which language a neologism originated. For this reason, lexicographer Philip Gove attributed many such words to the "international scientific vocabulary" (ISV) when compiling Webster's Third New International Dictionary (1961). Another active word-formation process in English is acronyms,[214] words formed by pronouncing as a single word abbreviations of longer phrases (e.g. NATO, laser).

Word origins[编辑]

English, besides forming new words from existing words and their roots, also borrows words from other languages. This process of adding words from other languages is commonplace in many world languages, but English is characterised as being especially open to borrowing of foreign words throughout the last 1,000 years.[216] The most commonly used words in English are West Germanic.[217] The words in English learned first by children as they learn to speak, particularly the grammatical words that dominate the word count of both spoken and written texts, are the Germanic words inherited from the earliest periods of the development of Old English.[14]

But one of the consequences of long language contact between French and English in all stages of their development is that the vocabulary of English has a very high percentage of "Latinate" words (derived from French, especially, and also from Latin or from other Romance languages). French words from various periods of the development of French now make up one-third of the vocabulary of English.[218] Words of Old Norse origin have entered the English language primarily from the contact between Old Norse and Old English during colonisation of eastern and northern England. Many of these words are part of English core vocabulary, such as egg or knife.[219]

English has also borrowed many words directly from Latin, the ancestor of the Romance languages, during all stages of its development.[212][14] Many of these words were earlier borrowed into Latin from Greek. Latin or Greek are still highly productive sources of stems used to form vocabulary of subjects learned in higher education such as the sciences, philosophy, and mathematics.[220] English continues to gain new loanwords and calques ("loan translations") from languages all over the world, and words from languages other than the ancestral Anglo-Saxon language make up about 60 percent of the vocabulary of English.[221]

English has formal and informal speech registers, and informal registers, including child directed speech, tend to be made up predominantly of words of Anglo-Saxon origin, while the percentage of vocabulary that is of Latinate origin is higher in legal, scientific, and academic texts.[222][223]

English loanwords and calques in other languages[编辑]

English has a strong influence on the vocabulary of other languages.[218][224] The influence of English comes from such factors as opinion leaders in other countries knowing the English language, the role of English as a world lingua franca, and the large number of books and films that are translated from English into other languages.[225] That pervasive use of English leads to a conclusion in many places that English is an especially suitable language for expressing new ideas or describing new technologies. Among varieties of English, it is especially American English that influences other languages.[226] Some languages, such as Chinese, write words borrowed from English mostly as calques, while others, such as Japanese, readily take in English loanwords written in sound-indicating script.[227] Dubbed films and television programmes are an especially fruitful source of English influence on languages in Europe.[227]

Writing system[编辑]

Since the ninth century, English has been written in a Latin alphabet (also called Roman alphabet). Earlier Old English texts in Anglo-Saxon runes are only short inscriptions. The great majority of literary works in Old English that survive to today are written in the Roman alphabet.[33] The modern English alphabet contains 26 letters of the Latin script: a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i, j, k, l, m, n, o, p, q, r, s, t, u, v, w, x, y, z (which also have capital forms: A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I, J, K, L, M, N, O, P, Q, R, S, T, U, V, W, X, Y, Z).

| 英语字母 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | a | B | b | C | c | D | d | E | e | F | f | G | g | H | h | I | i | J | j | K | k | L | l | M | m | N | n | O | o |

| P | p | Q | q | R | r | S | s | T | t | U | u | V | v | W | w | X | x | Y | y | Z | z | ||||||||

The spelling system, or orthography, of English is multi-layered, with elements of French, Latin, and Greek spelling on top of the native Germanic system.[228] Further complications have arisen through sound changes with which the orthography has not kept pace.[47] Compared to European languages for which official organisations have promoted spelling reforms, English has spelling that is a less consistent indicator of pronunciation and standard spellings of words that are more difficult to guess from knowing how a word is pronounced.[229] There are also systematic spelling differences between British and American English. These situations have prompted proposals for spelling reform in English.[230]

Although letters and speech sounds do not have a one-to-one correspondence in standard English spelling, spelling rules that take into account syllable structure, phonetic changes in derived words, and word accent are reliable for most English words.[231] Moreover, standard English spelling shows etymological relationships between related words that would be obscured by a closer correspondence between pronunciation and spelling, for example the words photograph, photography, and photographic,[231] or the words electricity and electrical. While few scholars agree with Chomsky and Halle (1968) that conventional English orthography is "near-optimal",[228] there is a rationale for current English spelling patterns.[232] The standard orthography of English is the most widely used writing system in the world.[233] Standard English spelling is based on a graphomorphemic segmentation of words into written clues of what meaningful units make up each word.[234]

Readers of English can generally rely on the correspondence between spelling and pronunciation to be fairly regular for letters or digraphs used to spell consonant sounds. The letters b, d, f, h, j, k, l, m, n, p, r, s, t, v, w, y, z represent, respectively, the phonemes /b, d, f, h, dʒ, k, l, m, n, p, r, s, t, v, w, j, z/. The letters c and g normally represent /k/ and /ɡ/, but there is also a soft c pronounced /s/, and a soft g pronounced /dʒ/. The differences in the pronunciations of the letters c and g are often signalled by the following letters in standard English spelling. Digraphs used to represent phonemes and phoneme sequences include ch for /tʃ/, sh for /ʃ/, th for /θ/ or /ð/, ng for /ŋ/, qu for /kw/, and ph for /f/ in Greek-derived words. The single letter x is generally pronounced as /z/ in word-initial position and as /ks/ otherwise. There are exceptions to these generalisations, often the result of loanwords being spelled according to the spelling patterns of their languages of origin[231] or proposals by pedantic scholars in the early period of Modern English to mistakenly follow the spelling patterns of Latin for English words of Germanic origin.[235]

For the vowel sounds of the English language, however, correspondences between spelling and pronunciation are more irregular. There are many more vowel phonemes in English than there are vowel letters (a, e, i, o, u, w, y). As a result of a smaller set of single letter symbols than the set of vowel phonemes, some "long vowels" are often indicated by combinations of letters (like the oa in boat, the ow in how, and the ay in stay), or the historically based silent e (as in note and cake).[232]

The consequence of this complex orthographic history is that learning to read can be challenging in English. It can take longer for school pupils to become independently fluent readers of English than of many other languages, including Italian, Spanish, or German.[236] Nonetheless, there is an advantage for learners of English reading in learning the specific sound-symbol regularities that occur in the standard English spellings of commonly used words.[231] Such instruction greatly reduces the risk of children experiencing reading difficulties in English.[237][238] Making primary school teachers more aware of the primacy of morpheme representation in English may help learners learn more efficiently to read and write English.[239]

English writing also includes a system of punctuation that is similar to the system of punctuation marks used in most alphabetic languages around the world. The purpose of punctuation is to mark meaningful grammatical relationships in sentences to aid readers in understanding a text and to indicate features important for reading a text aloud.[240]

Dialects, accents, and varieties[编辑]

Dialectologists identify many English dialects, which usually refer to regional varieties that differ from each other in terms of patterns of grammar, vocabulary, and pronunciation. The pronunciation of particular areas distinguishes dialects as separate regional accents. The major native dialects of English are often divided by linguists into the two extremely general categories of British English (BrE) and North American English (NAE).[241] There also exists a third common major grouping of English varieties: Southern Hemisphere English, the most prominent being Australian and New Zealand English.

United Kingdom and Ireland[编辑]

As the place where English first evolved, the British Isles, and particularly England, are home to the most diverse dialects. Within the United Kingdom, the Received Pronunciation (RP), an educated dialect of South East England, is traditionally used as the broadcast standard, and is considered the most prestigious of the British dialects. The spread of RP (also known as BBC English) through the media has caused many traditional dialects of rural England to recede, as youths adopt the traits of the prestige variety instead of traits from local dialects. At the time of the Survey of English Dialects, grammar and vocabulary differed across the country, but a process of lexical attrition has led most of this variation to disappear.[242]

Nonetheless this attrition has mostly affected dialectal variation in grammar and vocabulary, and in fact only 3 percent of the English population actually speak RP, the remainder speaking regional accents and dialects with varying degrees of RP influence.[243] There is also variability within RP, particularly along class lines between Upper and Middle class RP speakers and between native RP speakers and speakers who adopt RP later in life.[244] Within Britain there is also considerable variation along lines of social class, and some traits though exceedingly common are considered "non-standard" and are associated with lower class speakers and identities. An example of this is H-dropping, which was historically a feature of lower class London English, particularly Cockney, and can now be heard in the local accents of most parts of England — yet it remains largely absent in broadcasting and among the upper crust of British society.[245]

English in England can be divided into four major dialect regions, Southwest English, South East English, Midlands English, and Northern English. Within each of these regions several local subdialects exist: Within the Northern region, there is a division between the Yorkshire dialects, and the Geordie dialect spoken in Northumbria around Newcastle, and the Lancashire dialects with local urban dialects in Liverpool (Scouse) and Manchester (Mancunian). Having been the centre of Danish occupation during the Viking Invasions, Northern English dialects, particularly the Yorkshire dialect, retain Norse features not found in other English varieties.[246]

Since the 15th century, southeastern England varieties centred around London, which has been the centre from which dialectal innovations have spread to other dialects. In London, the Cockney dialect was traditionally used by the lower classes, and it was long a socially stigmatised variety. The spread of Cockney features across the south-east led the media to talk of Estuary English as a new dialect, but the notion was criticised by many linguists on the grounds that London had influencing neighbouring regions throughout history.[247][248][249] Traits that have spread from London in recent decades include the use of intrusive R (drawing is pronounced drawring /ˈdrɔːrɪŋ/), t-glottalisation (Potter is pronounced with a glottal stop as Po'er /poʔʌ/), and the pronunciation of th- as /f/ (thanks pronounced fanks) or /v/ (bother pronounced bover). [250]

Scots is today considered a separate language from English, but it has its origins in early Northern Middle English[251] and developed and changed during its history with influence from other sources, particularly Scots Gaelic and Old Norse. Scots itself has a number of regional dialects. And in addition to Scots, Scottish English are the varieties of Standard English spoken in Scotland, most varieties are Northern English accents, with some influence from Scots.[252]

In Ireland, various forms of English have been spoken since the Norman invasions of the 11th century. In County Wexford, in the area surrounding Dublin, two extinct dialects known as Forth and Bargy and Fingallian developed as offshoots from Early Middle English, and were spoken until the 19th century. Modern Irish English, however has its roots in English colonisation in the 17th century. Today Irish English is divided into Ulster English, the Northern Ireland dialect with strong influence from Scots, as well as various dialects of the Republic of Ireland. Like Scottish and most North American accents, almost all Irish accents preserve the rhoticity which has been lost in the dialects influenced by RP.[20][253]

North America[编辑]

American English is fairly homogeneous compared to British English. Today, American accent variation is often increasing at the regional level and decreasing at the very local level,[254] though most Americans still speak within a phonological continuum of similar accents,[255] known collectively as General American (GA), with differences hardly noticed even among Americans themselves (such as Midland and Western American English).[256][257][258] In most American and Canadian English, rhoticity (or r-fulness) is dominant, with non-rhoticity (r-dropping) becoming associated with lower prestige and social class especially after World War II; this contrasts with the situation in England, where non-rhoticity has become the standard.[259]

Separate from GA are American dialects with clearly distinct sound systems, historically including Southern American English, English of the coastal Northeast (famously including Eastern New England English and New York City English), and African American Vernacular English, all of which are historically non-rhotic. Canadian English, except for the Atlantic provinces and perhaps Quebec, may be classified under GA as well, but it often shows raising of certain vowels, /aɪ/ and /aʊ/, before voiceless consonants, as well as distinct norms for written and pronunciation standards.[260]

In Southern American English, the largest American "accent group" outside of GA,[261] rhoticity now strongly prevails, replacing the region's historical non-rhotic prestige.[262][263][264] Southern accents are colloquially described as a "drawl" or "twang,"[265] being recognised most readily by the Southern Vowel Shift that begins with glide-deleting in the /aɪ/ vowel (e.g. pronouncing spy almost like spa), the "Southern breaking" of several front pure vowels into a gliding vowel or even two syllables (e.g. pronouncing the word "press" almost like "pray-us"),[266] the pin–pen merger, and other distinctive phonological, grammatical, and lexical features, many of which are actually recent developments of the 19th century or later.[267]

Today spoken primarily by working- and middle-class African Americans, African American Vernacular English (AAVE) is also largely non-rhotic and likely originated among enslaved Africans and African Americans influenced primarily by the non-rhotic, non-standard English dialects of the Old South. A minority of linguists,[268] contrarily, propose that AAVE mostly traces back to African languages spoken by the slaves who had to develop a pidgin or Creole English to communicate with slaves of other ethnic and linguistic origins.[269] AAVE shares important commonalities with older Southern American English and so probably developed to a highly coherent and homogeneous variety in the 19th or early 20th century. AAVE is commonly stigmatised in North America as a form of "broken" or "uneducated" English, also common of modern Southern American English, but linguists today recognise both as fully developed varieties of English with their own norms shared by a large speech community.[270][271]

Australia and New Zealand[编辑]

Since 1788, English has been spoken in Oceania, and Australian English has developed as a first language of the vast majority of the inhabitants of the Australian continent, its standard accent being General Australian. The English of neighbouring New Zealand has to a lesser degree become an influential standard variety of the language.[272] Australian and New Zealand English are each other's closest relatives with few differentiating characteristics, followed by South African English and the English of southeastern England, all of which have similarly non-rhotic accents, aside from some accents in the South Island of New Zealand. Australian and New Zealand English stand out for their innovative vowels: many short vowels are fronted or raised, whereas many long vowels have diphthongised. Australian English also has a contrast between long and short vowels, not found in most other varieties. Australian English grammar aligns closely to British and American English; like American English, collective plural subjects take on a singular verb (as in the government is rather than are).[273][274] New Zealand English uses front vowels that are often even higher than in Australian English.[275][276][277]

Africa, the Caribbean, and South Asia[编辑]